Detection of intraocular infections relies heavily on molecular diagnostics. A fundamental challenge is that only 100–300 μL of intraocular fluid can be safely obtained at any given time for diagnostic testing. The most widely available molecular diagnostic panel for infections in ophthalmology includes 4 separate pathogen-directed polymerase chain reactions (PCRs): cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), varicella zoster virus (VZV), and Toxoplasma gondii. Not surprisingly, more than 50% of all presumed intraocular infections fail to have a pathogen identified.1

Metagenomic deep sequencing has the potential to improve diagnostic yield as it is unbiased and hypothesis-free – it can theoretically detect all pathogens in a clinical sample.2, 3 Previously, we demonstrated that unbiased RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) of intraocular fluid detects fungi, parasites, DNA and RNA viruses in uveitis patients.2 One obvious drawback regarding RNA-seq is that optimal RNA sequencing requires proper specimen handling, including either flash-freezing or immediate placement the specimen on dry ice. While commercial room-temperature RNA-preservatives may address this issue, practicing ophthalmologists may find these collection techniques impractical in an outpatient setting. For pathogens with DNA genomes, metagenomic DNA sequencing (DNA-seq) can circumvent this challenge, as DNA is more tolerant of ambient temperature. The purpose of this study was to compare the performance of DNA-seq with conventional pathogen-directed PCRs to diagnose intraocular infections.

De-identified archived vitreous samples received by the Proctor Foundation for pathogen-directed PCR testing from 2010–2015 were included. Samples were previously boiled and stored at −80C. A total of 31 pathogen-positive reference samples and 36 pathogen-negative reference samples by Proctor PCRs were randomized and subjected to DNA-seq. The sensitivity and specificity of the Proctor’s pathogen-directed PCRs range from 85–100% and 98–100%, respectively. The DNA-seq workflow included the following steps: 50 μL of each vitreous sample was used to isolate DNA using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, MD) per the manufacturer’s recommendations, 5 μL of the extracted DNA were used to prepare libraries using the Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, CA) and amplified with 12 PCR cycles, and library size and concentration were determined as described.2 Samples were then sequenced to an average depth of 15 X 106 reads/sample on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 instrument using 125 nucleotide (nt) paired-end sequencing. Sequencing data were analyzed using a rapid computational pipeline developed in-house to classify sequencing reads and identify potential pathogens against the entire NCBI nucleotide reference database.2 Any infectious agent that had ≥ 2 non-overlapping reads to the reference pathogen genome was considered positive if it met both of the following criteria: (1) It is a pathogen known to be a cause of infectious uveitis, and (2) reads from this pathogen were not present in the no-template (“water only”) control on the same run and library preparation. Discrepant samples were evaluated at the CLIA-certified Stanford Clinical Microbiology and Clinical Virology laboratories, except for HTLV-1 which was confirmed at UCSF using primers targeting the tax gene4 and subsequent amplicon sequencing (Elim Biosciences, CA). Laboratory personnel involved in sample preparation, analysis, and confirmatory testing were masked to the reference PCR results until all analyses were completed.

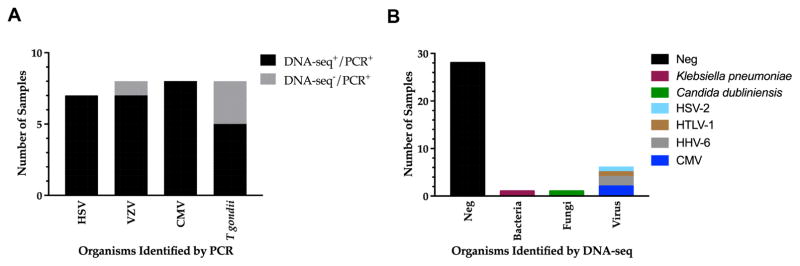

Of the 31 positive-reference samples tested, 27 samples were identified correctly with DNA-seq (Figure 1A, Table S1, available online at www.aaojournal.org). 3 samples positive for T. gondii and 1 sample positive for VZV by directed-PCR were not detected by DNA-seq. The positivity of these 4 samples was confirmed by directed real-time PCRs. The cycle threshold for VZV was 28.2, while the cycle thresholds for the three T. gondii samples ranged from 27–36.5. The positive agreement between DNA-seq and directed-PCR was 87%.

Figure 1. Detection of infectious agents by pathogen-directed PCRs and DNA-seq.

(A) Metagenomic DNA sequencing identified 27 out of 31 (87%) infectious agents detected by pathogen-directed PCRs. (B) Metagenomic DNA sequencing detected bacteria, fungi, and DNA viruses in an additional 8 samples that were negative by pathogen-directed PCRs. Abbreviations: cytomegalovirus, CMV; herpes simplex virus, HSV; varicella zoster virus, VZV; Toxoplasma gondii, T. gondii; human T-cell leukemia virus type 1, HTLV-1; human herpesvirus 6, HHV-6.

Thirty-six archived vitreous samples that tested negative by all Proctor pathogen-directed PCRs (CMV, VZV, HSV, and T. gondii) were randomly selected for DNA-seq. 28 out of 36 samples yielded no additional pathogen (Figure 1B, Table S1, available online at www.aaojournal.org), while 8 samples (22%) resulted in 6 additional pathogens either not detected or not tested with pathogen-directed PCRs. Those organisms included CMV, HHV-6, HSV-2, HTLV-1, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Candida dubliniensis. All of these organisms are known to cause infectious uveitis (Figure 1B). The results for HHV-6, HTLV-1, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Candida dubliniensis were confirmed. Two samples tested positive for HSV-2 and CMV by DNA-seq were not confirmed by directed-PCR. Here, it was unclear if DNA-seq can achieve higher sensitivity for CMV and HSV-2 compared to PCR, or whether these were false positive results by DNA-seq, as these samples yielded only 2 reads on DNA-seq. It should be noted that DNA-seq detected 100% of all samples that tested positive for CMV and HSV by PCR.

An advantage of metagenomic deep sequencing is the ability to apply sequence information to infer the phenotypic behavior of the identified pathogen. We compared samples in which CMV sequences were adequately recovered for the UL54 and UL97 genes, coding for the DNA polymerase and phosphotransferase respectively, and compared to a CMV antiviral drug resistance database developed at Stanford University.5 Of the 7 samples analyzed, 3 had mutations in UL97 (phosphotransferase) that confer ganciclovir and valganciclovir resistance. Two samples were found to have C592G mutations, and 1 sample had both C592G and L595S mutations (Table S2, available online at www.aaojournal.org).

In summary, we showed that metagenomic DNA sequencing was highly concordant with pathogen-directed PCRs, despite non-ideal sample handling conditions (boiled, long-term frozen). The unbiased nature of metagenomics DNA sequencing allowed an expanded scope of pathogen detection, including bacteria, fungal species, and viruses, resolving 22% of cases that had previously escaped detection by routine pathogen-specific PCRs available to ophthalmologists, while concurrently provide drug resistance information. The number of missed pathogens reported in this study is likely an underestimation, as DNA-seq alone cannot detect RNA viruses (e.g., rubella), although a larger sample size may be more representative. These data suggests a practical diagnostic decision tree whereby samples negative by routine PCR are then advanced to both metagenomic DNA and RNA sequencing. This approach will not only complement the current diagnostic paradigm in ophthalmology but also allow for a more comprehensive characterization of the etiology of infectious uveitis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the UCSF Resource Allocation Program for Junior Investigators in Basic and Clinical/Translation Science (T.D.); Howard Hughes Medical Institute (J.L.D.); Research to Prevent Blindness Career Development Award (T.D.); the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K08EY026986 (T.D.). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or HHMI.

Footnotes

Meeting Presentation:

This work was presented at the American Uveitis Society (AUS) meeting at the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) Annual Meeting, 2016. A version of this manuscript is published as a preprint on BioRxiv (http://biorxiv.org).

Financial Disclosures:

None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Taravati P, Lam D, Van Gelder RN. Role of molecular diagnostics in ocular microbiology. Curr Ophthalmol Rep. 2013;1(4) doi: 10.1007/s40135-013-0025-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doan T, Wilson MR, Crawford ED, et al. Illuminating uveitis: metagenomic deep sequencing identifies common and rare pathogens. Genome Med. 2016;8(1):90. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0344-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graf EH, Simmon KE, Tardif KD, et al. Unbiased Detection of Respiratory Viruses by Use of RNA Sequencing-Based Metagenomics: a Systematic Comparison to a Commercial PCR Panel. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54(4):1000–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03060-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunetto GS, Massoud R, Leibovitch EC, et al. Digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) for the precise quantification of human T-lymphotropic virus 1 proviral loads in peripheral blood and cerebrospinal fluid of HAM/TSP patients and identification of viral mutations. J Neurovirol. 2014;20(4):341–51. doi: 10.1007/s13365-014-0249-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sahoo MK, Lefterova MI, Yamamoto F, et al. Detection of cytomegalovirus drug resistance mutations by next-generation sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(11):3700–10. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01605-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.