Abstract

Adolescence is a period of transition that is associated with increased levels of stress and a heightened propensity to initiate drug use. Neuronal development is still occurring during this transitional period, which includes the continued development of the dopamine system during the adolescent period. In the present study, the effects of pre-test handling on cocaine-induced locomotor activity were investigated among female adolescent and young adult rats upon presentation to a novel environment. On postnatal days (PND) 41–44 and 56–59 animals were handled (b.i.d.) in the colony room for 3 min. On PND 45 or PND 60, animals were removed from the colony room, weighed, and administered an acute injection of either cocaine or saline and presented to a novel environment where behavior was recorded for 30 min. Adolescent females (PND 45) that were handled prior to cocaine administration demonstrated elevated levels of cocaine-induced activity relative to their age-matched non-handled counterparts and also to their handled-adult counterparts. In contrast, among non-handled animals, young adults (PND 60) exhibited elevated drug-induced locomotion at several time points during the trial. Non-handled adolescent animals demonstrated the previously described “hyporesponsive” behavioral profile relative to their non-handled adult counterparts. The results from the present experiment indicate that adolescent animals may be more sensitive to basic laboratory manipulations such as pre-test handling, and care must be taken when utilizing adolescent animals in behavioral testing. Handling appears to be a sensitive manipulation in elucidating differences in cocaine-induced behavioral activation between ages.

Keywords: Handling, Adolescent, Female, Cocaine, Locomotor activity, Novel environment

1. Introduction

Adolescence is a developmental period in which the propensity to initiate drug use is heightened. There has been a fairly stable level of illicit drug use in adolescents since 2000 [1]. The age of onset of drug-related behavior is an important predictor of later drug use [2,3] and the progression to addiction appears to be accelerated among adolescents relative to adults [4]. Given these facts and that females are more susceptible to the behavioral activational properties of cocaine [5–7], it is vital to assess the effects of cocaine administration in females.

Handling is a basic laboratory procedure that has been used to acclimate animals to experimental manipulation. Previously, investigators have found that gentle handling (i.e., postweaning gentling) increases locomotor activity in a novel environment in naïve animals [8]. Other investigators have assessed the effects of pre-test handling and found that this basic laboratory manipulation increases open-field baseline locomotor activity when handled animals are presented to a novel environment [9,10] and open-field exploration appears to be increased by pre-test handling [9–11]. Handled adolescent rats displayed elevated locomotor activity to amphetamine when compared to animals exposed to chronic social stress [12]. When measuring cocaine intake, there were no differences reported among animals that were handled as compared to controls [13]. Together these studies show that handling is a manipulation that impacts open-field locomotor activity and exploration.

Recently, it has been demonstrated that handling male rats increased cocaine-induced locomotor activity in adolescent but not young adults [14]. Given important sex differences across development [15], it would be interesting to examine if this pattern is also evident for adolescent females. Importantly, females appear to be more sensitive to the effects of acute cocaine administration [5,6,16]. Therefore, the present study investigated the effects of prior handling on cocaine-induced locomotor activity in a novel environment in adolescent and young adult female rats. The handling manipulation was expected to increase cocaine-induced locomotor activity in female adolescent versus young adult animals.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Subjects

Seventy-nine female Sprague–Dawley rats, derived from established breeding pairs at the University of South Florida, Tampa (Harlan Laboratories, IN), were used in the present study. Litters were sexed and culled to 10 pups per litter on postnatal day (PND) 1, with the date of birth designated as PND 0. Pups were housed with their respective dams until PND 21 when they were weaned and housed in groups of three with same-sex littermates. The colony room was maintained in a humidity- and temperature-controlled vivarium on a 12:12 h light/dark cycle, with lights on from 0700 to 1900 hours. Animals were allowed ad libitum access to food and water in the home cage. At the time of behavioral testing, animals weighed between 136 and 229 g (PND 45 μ =167.0 g; PND 60 μ =208.8 g). Each animal was tested at only one age, PND 45 or PND 60. No more than one female pup per litter was used in any given condition. In all respects, maintenance and treatment of the animals were within the guidelines for animal care by the National Institutes of Health [17].

2.2. Apparatus

The apparatus consisted of an open circular field with a black Plexiglas floor (D = 96.5 cm) and an opaque circular barrier made of Plexiglas (H = 45.7 cm) in which animals were allowed free access to move about. A camera was suspended above the dimly lit open field and movement (cm) of the animal was digitally recorded. This signal was tracked, quantified, and analyzed using an Ethovision video tracking system (Noldus Information Technology, Utrecht, Netherlands).

2.3. Procedure

Female adolescent (PND 41–45) and young adult (PND 56–60) animals were randomly assigned to either the handled (H) or non-handled (NH) treatment group. Handling was conducted in the colony room over a period of four consecutive days, (PND 41–44; PND 56–59) twice daily for 3 min (between 1000 and 1100 hours and 1600–1700 hours, respectively). Handling consisted of removing an individual animal from the home cage and allowing it to sit and/or move about the experimenter’s hands and arms for 3 min, after which the animal was returned to the home cage with littermates. Experimenters always wore a white lab coat to control for visual cues and gloves were not worn. Non-handled animals were left undisturbed until the target day, PND 45 or PND 60, except for regular cage maintenance, which occurred for all animals. On the target day (between 1000 and 1300 hours), PND 45 or PND 60, animals were removed from the colony room, weighed, and administered an acute injection of either cocaine (30 mg/kg/ip; a dose which we have found to induce a significant conditioned place preference in PND 45 animals; unpublished data) or saline (0.9% NaCl), immediately placed on the novel circular open field for 30 min and behavior was recorded.

2.4. Design and analyses

Data for total distance moved (TDM; cm) for the entire 30-min session were analyzed using a three-factor between-subjects ANOVA for handling (2; handled, non-handled), age (2; PND 45, PND 60) and drug (2; saline, 30 mg/kg cocaine). Additionally, a detailed time-course analysis was conducted with data for TDM analyzed across the 30-min trial in 3-min intervals using a four-factor mixed-design ANOVA for handling (2; handled, non-handled), age (2; PND 45, PND 60), drug (2; 30 mg/kg cocaine, saline), with time as a repeated measure. Subsequent planned comparisons (Fisher’s protected least significant difference test and simple effects) were used to isolate handling effects.

3. Results

3.1. Thirty-minute trial

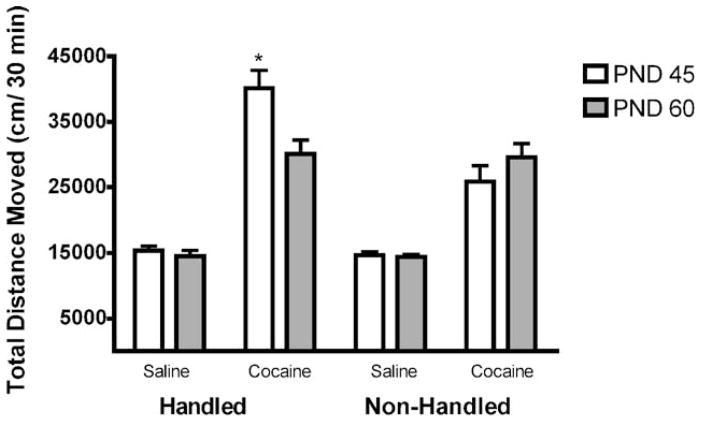

There was an interesting relationship between handling and age on cocaine-induced locomotor activity. Fig. 1 illustrates that cocaine-induced locomotor activity was heightened in handled-adolescent females relative to handled-adult females across the entire 30-min trial as demonstrated by a significant three-way handling by age by drug interaction (F(1,71)=6.4, p <0.05). This effect is supported by significant two-way interactions of handling by age (F(1,71)=7.5, p <0.01) and handling by drug (F(1,71)=7.3, p <0.01). Additionally, there was a significant main effect of handling (F(1, 71)= 9.0, p <0.01) and drug (F(1,71)=162.9, p <0.01).

Fig. 1.

Total distance moved (TDM) collapsed across the entire 30-min session in PND 45 and PND 60 handled and non-handled animals. Data indicate that overall, cocaine-induced locomotor activity is significantly elevated in PND 45 handled animals treated with cocaine relative to non-handled PND 60 animals and all non-handled animals treated with cocaine when collapsed across the entire 30-min period. *Indicates significant difference from PND 60-handled and all non-handled animals (p < 0.05). Bars represent mean±SEM.

3.2. Time-course analysis

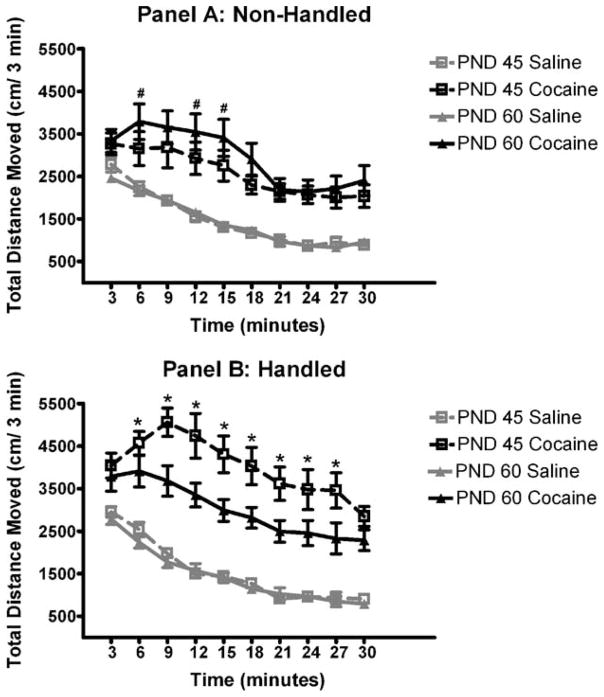

A significant main effect of time (F(9, 639) = 71.4, p <0.001), along with a significant time by drug interaction (F(9,639)=5.9, p <0.001) existed, indicating that cocaine-induced increases in TDM continued to be significantly elevated relative to saline controls for the entire duration of the 30-min exposure to the novel environment. Fig. 2 demonstrates the time-course of the relationship between handling, age, and cocaine on locomotor activity as confirmed from planned comparisons. Focusing on panel A, non-handled PND 45 animals treated with cocaine had significantly lower levels of cocaine-induced locomotor activity at time points 6, 12 and 15 min of the trial relative to PND 60 animals (p <0.05). This behavioral hyporesponsiveness to cocaine has been reported previously in the literature in periadolescent animals [18,19]. In contrast, focusing on panel B, PND 45 handled animals treated with cocaine had significantly greater levels of cocaine-induced locomotor activity from 6 to 27 min of the trial relative to their adult counterparts (p <0.05). A similar effect has recently been demonstrated in adolescent males [14]. Additionally, cocaine-induced locomotor activity was elevated in PND 45 handled females relative to PND 45 non-handled animals across the entire 30-min trial (p <0.05).

Fig. 2.

Panel A: total distance moved in three-min intervals for PND 45 and PND 60 non-handled animals. Panel B: total distance moved in three-min intervals for PND 45 and PND 60 handled animals. Data indicate that adolescent (PND 45) animals that are handled prior to exposure to an inescapable novel environment and treated with cocaine exhibit a significant increase in TDM from 6 to 27 min of the trial, when compared to their young adult (PND 60) handled counterparts. Additionally, among non-handled animals, PND 60 cocaine-treated animals demonstrate elevated locomotor activity at 6, 12 and 15 min of the session relative to their adolescent counterparts. #Indicates significant difference of cocaine-induced locomotor activity between non-handled PND 45 and non-handled PND 60 animals (6, 12 and 15 min of trial; p <0.05). *Indicates significant difference of cocaine-induced locomotor activity between handled PND 45 animals and handled PND 60 animals (6–27 min of trial; p <0.05). Handled-adolescent animals exhibit greater cocaine-induced locomotor activity relative to their non-handled counterparts across the entire trial. Data points represent mean±SEM.

4. Discussion

In general, handling had a unique effect in adolescent animals treated with cocaine. Handling is used as a control for stress manipulations (ex. Refs. [12,20]) and even a single session of handling has been shown to alter behavior as measured by activity in the elevated plus maze [21]. In previous work, handling was observed to increase locomotor activity among naïve gently handled (i.e., gentled) females relative to non-handled females, but this pattern was not evident on the first trial [22]. This effect is similar to the saline-treated animals in the present study, with no significant differences of locomotor activity between handled and non-handled animals. It is possible that this same pattern may have developed in females in the present experiment, but locomotor activity was assessed in response to acute cocaine or saline only. Bronstein and colleagues [22] suggest that juvenile females may be more sensitive to postweaning handling and that gentled females may find the novel environment in which they were tested to be less aversive relative to non-handled females.

In the present study, cocaine increased locomotor activity among all animals relative to saline controls. This effect persisted even at the end of the 30-min session, a result previously observed in males [14]. However, cocaine-induced increases in activity were modulated by the effects of handling and age. Adolescent-handled females demonstrated increased cocaine-induced activity relative to their adult counterparts. Normal laboratory handling has been shown to alter naloxone withdrawal behavior in female rats [23]. Pre-test handling appears to alleviate anxiogenic effects on baseline locomotor activity and exploration [9–11,24]. This reduction in experimenter-induced stress is likely to prove beneficial in uncovering drug-induced effects that may be modulated by stress. It appears that handling that occurs during the postweaning period decreases levels of neophobia [11]. The effects of the handling manipulation on cocaine-induced behavioral activation in the present experiment may be attributed to the fact that adolescent animals have been suggested to possess reduced neophobia in conjunction with the reduced neophobia that the handling manipulation exerts on open-field activity.

HPA axis activation has been suggested to modulate the reinforcing effects of psychostimulants, such as cocaine [25–27], and acute cocaine increases stress-related hormones such as ACTH and corticosterone [25]. Corticosterone does not appear to modulate the behavioral activating effects of cocaine at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg cocaine in adult animals [28]. Additionally, it has been suggested that higher doses of cocaine (e.g., that fall on the descending limb of the dose response curve) increase plasma corticosterone levels above the “critical reward threshold” and once this threshold is crossed any further increases in plasma corticosterone would not alter the behavioral effects of a higher dose of cocaine [25,28], as used in the present experiment. Adolescent animals have been suggested to be better able to cope with a mildly stressful stimulus (e.g., novel environment, acute cocaine injection) [12]. Therefore, handling may equate adolescent and adult animals with regard to experimenter manipulation and the differences observed in cocaine-induced behavioral activation mediated by the novel environment and the acute cocaine administration.

Alternatively, it has been postulated that repeated increases in stress-related hormones would induce a compensatory response for an acute stressor (i.e., novel environment or injection of cocaine) which would render the subject more responsive to drugs of abuse [26]. Thus, another possible explanation of the increased level of TDM among handled-adolescent females treated with cocaine is that the handling manipulation may be a mild stressor, which the animal habituates to, causing a repeated activation of the stress system resulting in a higher locomotor response to an acute injection of cocaine upon presentation to a novel environment. Since handling-habituated adolescent females exhibited greater levels of cocaine-induced locomotor activity relative to their non-handled adolescent and handled-adult counterparts, this difference in activity could represent a vulnerability to drugs of abuse that is unique to adolescents.

Adolescents have been reported to have higher basal corticosterone levels [29], but a blunted stress response in comparison to adult animals [30]. There may be a lower level of activation that is expressed behaviorally by adolescent animals in response to stress [29]. Adolescents have been reported to habituate relatively quickly to repeated stress [31] and are better able to cope with mildly stressful stimuli [12]. Additionally, it has been suggested that locomotor activity in adolescent animals may be enhanced in less stressful conditions [2]. Therefore, since adolescent animals have been reported to be able to cope better with a mild stressor, the less activated stress-response system and the anxiolytic properties of handling on locomotor activity may mediate the age-related differences in cocaine-stimulated locomotor activity in adolescent female rats.

Our results indicate that even without controlling for differences in stage of estrous cycle, a clear difference exists in cocaine-induced behavioral activation that is unique to handled adolescent females. Previously it has been suggested that cocaine administration during the periadolescent period can induce changes in the estrous cycle [32]. It has been shown in adult females that estrous cycle can influence cocaine-induced activity [33]. Additionally, vaginal lavage has been shown to attenuate cocaine-induced activity [34]. Future research should address the effects of estrous cycle on acute cocaine-induced locomotor activity in handling-habituated adolescent versus adult female rats.

In the present study, handling uniquely impacted cocaine-induced locomotor activity in that handling increased cocaine stimulated activity among adolescent females above that of their non-handled adolescent and handled-adult counterparts. The effects of handling observed in the present study address some of the issues associated with the control that must be utilized in adolescent animal models. Both male [14] and female adolescent animals are differentially responsive to even subtle manipulations such as handling prior to testing. Adolescents have previously been suggested to have a hyporesponsive behavioral profile when administered an acute psychostimulant [3,18,29,35,36]. This effect was demonstrated in the present experiment among non-handled animals, with adults exhibiting elevated drug-induced locomotion at several time points relative to their adolescent counterparts. However, as demonstrated in the present and in previous experiments [14,29,37], an elevated level of behavioral activation was expressed in adolescents to an acute administration of a high dose of a psychostimulant. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that adolescent females are uniquely impacted by cocaine’s activating effects.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from NIDA: RO1DA14024.

References

- 1.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: overview of key findings, 2002. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2003. (NIH Publication No. 03-5374) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laviola G, Macri S, Morley-Fletcher S, Adriani W. Risk-taking behavior in adolescent mice: psychobiological determinants and early epigenetic influence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:19–31. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:417–63. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Estroff TW, Schwartz RH, Hoffmann NG. Adolescent cocaine abuse. Addictive potential, behavioral and psychiatric effects. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1989;28:550–5. doi: 10.1177/000992288902801201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chin J, Sternin O, Wu HB, Fletcher H, Perrotti LI, Jenab S, et al. Sex differences in cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2001;47:1089–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schindler CW, Carmona GN. Effects of dopamine agonists and antagonists on locomotor activity in male and female rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;72:857–63. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00770-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Haaren F, Meyer ME. Sex differences in locomotor activity after acute and chronic cocaine administration. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991;39:923–7. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson RW, Lippman LG. Exploration and activity in the gerbil and rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1972;80:439–48. doi: 10.1037/h0032999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmitt U, Hiemke C. Combination of open field and elevated plus-maze: a suitable test battery to assess strain as well as treatment differences in rat behavior. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1998;22:1197–215. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(98)00051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmitt U, Hiemke C. Strain differences in open-field and elevated plus-maze behavior of rats without and with pretest handling. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;59:807–11. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00502-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reboucas RC, Schmidek WR. Handling and isolation in three strains of rats affect open field, exploration, hoarding and predation. Physiol Behav. 1997;62:1159–64. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(97)00312-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kabbaj M, Isgor C, Watson SJ, Akil H. Stress during adolescence alters behavioral sensitization to amphetamine. Neuroscience. 2002;113:395–400. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marquardt AR, Ortiz-Lemos L, Lucion AB, Barros HM. Influence of handling or aversive stimulation during rats’ neonatal or adolescence periods on oral cocaine self-administration and cocaine withdrawal. Behav Pharmacol. 2004;15:403–12. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200409000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maldonado AM, Kirstein CL. Handling alters cocaine-induced activity in adolescent but not adult male rats. Physiol Behav. 2005;84:321–6. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersen SL, Rutstein M, Benzo JM, Hostetter JC, Teicher MH. Sex differences in dopamine receptor overproduction and elimination. Neuroreport. 1997;8:1495–8. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199704140-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Festa ED, Russo SJ, Gazi FM, Niyomchai T, Kemen LM, Lin SN, et al. Sex differences in cocaine-induced behavioral responses, pharmacokinetics, and monoamine levels. Neuropharmacology. 2004;46:672–87. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Institutes of Health. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1986. (DHEW publication no. 86-23) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spear LP, Brake SC. Periadolescence: age-dependent behavior and psychopharmacological responsivity in rats. Dev Psychobiol. 1983;16:83–109. doi: 10.1002/dev.420160203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spear LP, Brick J. Cocaine-induced behavior in the developing rat. Behav Neural Biol. 1979;26:401–15. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(79)91410-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sorg BA, Li N, Wu W, Bailie TM. Activation of dopamine D1 receptors in the medial prefrontal cortex produces bidirectional effects on cocaine-induced locomotor activity in rats: effects of repeated stress. Neuroscience. 2004;127:187–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lapin IP. Only controls: effect of handling, sham injection, and intraperitoneal injection of saline on behavior of mice in an elevated plus-maze. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 1995;34:73–7. doi: 10.1016/1056-8719(95)00025-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bronstein PM, Wolkoff FD, Levine WJ. Sex-related differences in rats open-field activity. Behav Biol. 1975;13:133–8. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6773(75)90913-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pierce TL, Raper C. The effects of laboratory handling procedures on naloxone-precipitated withdrawal behavior in morphine-dependent rats. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 1995;34:149–55. doi: 10.1016/1056-8719(95)00060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.File SE. The ontogeny of exploration in the rat: habituation and effects of handling. Dev Psychobiol. 1978;11:321–8. doi: 10.1002/dev.420110405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goeders NE. Stress and cocaine addiction. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;301:785–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.3.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marinelli M, Piazza PV. Interaction between glucocorticoid hormones, stress and psychostimulant drugs. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:387–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piazza PV, Le Moal M. Glucocorticoids as a biological substrate of reward: physiological and pathophysiological implications. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1997;25:359–72. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steketee JD, Goeders NE. Pretreatment with corticosterone attenuates the nucleus accumbens dopamine response but not the stimulant response to cocaine in rats. Behav Pharmacol. 2002;13:593–601. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200211000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adriani W, Laviola G. A unique hormonal and behavioral hyporesponsivity to both forced novelty and D-amphetamine in periadolescent mice. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:334–46. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi S, Kellogg CK. Adolescent development influences functional responsiveness of noradrenergic projections to the hypothalamus in male rats. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1996;94:144–51. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(96)80005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shalyapina VG, Ordyan NE, Pivina SG, Rakitskaya VV. Neuroendocrine mechanisms of the formation of adaptive behavior. Neurosci Behav Physiol. 1997;27:275–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02462894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raap DK, Morin B, Medici CN, Smith RF. Adolescent cocaine and injection stress effects on the estrous cycle. Physiol Behav. 2000;70:417–24. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00287-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Becker JB. Gender differences in dopaminergic function in striatum and nucleus accumbens. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;64:803–12. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00168-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walker QD, Nelson CJ, Smith D, Kuhn CM. Vaginal lavage attenuates cocaine-stimulated activity and establishes place preference in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;73:743–52. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00883-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laviola G, Adriani W, Terranova ML, Gerra G. Psychobiological risk factors for vulnerability to psychostimulants in human adolescents and animal models. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1999;23:993–1010. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(99)00032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laviola G, Wood RD, Kuhn C, Francis R, Spear LP. Cocaine sensitization in periadolescent and adult rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:345–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Catlow BJ, Kirstein CL. Heightened cocaine-induced locomotor activity in adolescent compared to adult female rats. J Psychopharmacol. doi: 10.1177/0269881105056518. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]