Abstract

Difficult participant recruitment is a consistent barrier to successful medical research. Potential participant registries represent an increasingly common intervention to overcome this barrier. A variety of models for registries exist, but few data are available to instruct their design and implementation. To provide such data, we surveyed 110 cognitively normal research participants enrolled in a longitudinal study of aging and dementia. Seventy-four (67%) individuals participated in the study. Most (78%, CI: 0.67, 0.87) participants were likely to enroll in a registry. Willingness to participate was reduced for registries that required enrollment through the Internet using a password (26%, CI: 0.16, 0.36) or through email (38%, CI: 0.27, 0.49). Respondents acknowledged their expectations that researchers share information about their health and risk for disease and their concerns that their data could be shared with for-profit companies. We found no difference in respondent preferences for registries that shared contact information with researchers, compared to honest broker models that take extra precautions to protect registrant confidentiality (28% versus 30%; p = 0.46). Compared to those preferring a shared information model, respondents who preferred the honest broker model or who lacked model preference voiced increased concerns about sharing registrant data, especially with for-profit organizations. These results suggest that the design of potential participant registries may impact the population enrolled, and hence the population that will eventually be enrolled in clinical studies. Investigators operating registries may need to offer particular assurances about data security to maximize registry enrollment but also must carefully manage participant expectations.

Keywords: Clinical trial, recruitment, registries

INTRODUCTION

Slow recruitment to clinical research delays translational science and medical advances, while inadequate recruitment can leave studies underpowered and result in bias or scientific error [1, 2]. Accordingly, interventions to improve recruitment are urgently needed, especially in research areas of great activity such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [3].

AD is the most common cause of dementia and is increasing in prevalence and cost at alarming rates [4]. Studies suggesting that successful therapeutic intervention will require very early treatment have led to the initiation of a variety of primary and secondary AD prevention trials [5]. Primary AD prevention trials typically enroll large populations (n = ~3000) of cognitively normal volunteers who are healthy and able to participate in lengthy (>5 year outcomes) studies [6]. Secondary prevention trials enroll populations most likely to demonstrate cognitive decline, based on biomarker or genetic enrichment [7], enabling shorter (3 year outcomes) smaller (n = ~1000) trials. As such, secondary prevention trials have relatively high screen failure rates, and still require large populations be screened to achieve necessary sample sizes [8]. In all cases, improved methods of participant recruitment are needed to ensure trial success.

Potential participant registries represent an increasingly common intervention to overcome slow recruitment, including recruitment to AD trials [9–13]. Most clinical studies undertake serial recruitment of clinical patients or engage in prospective community outreach. In contrast, potential participant registries are repositories of individuals who have granted permission to be contacted regarding studies for which they might be eligible. At the initiation of a new study, a large number of individuals who may meet study inclusion criteria and are likely to be willing to participate can be contacted and immediately screened for eligibility. Thus, a portion (or the entirety) of the needed sample size may be achieved rapidly.

A variety of potential participant registry models can be implemented, each of which is associated with unique cost, burden, and data considerations. Some large registries, such as the Alzheimer’s Association’s TrialMatch [14] and the Alzheimer’s Prevention Registry (APR; http://www.endalznow.org), collect contact and demographic information at registration [15, 16]. After launching the APR, it was discovered that the requirement of creating a password for online registration was a barrier to registry recruitment and the requirement was eliminated [17]. Other registries, such as the Wisconsin Registry for AD Prevention, operate as cohort studies, collecting traditional written informed consent and performing longitudinal clinical, cognitive, genetic, and biomarker testing on registrants, theoretically permitting the identification of eligible secondary AD prevention trial participants [18]. The Brain Health Registry (http://www.brainhealthregistry.org) represents a hybrid approach, using Internet-based enrollment to minimize study burden and on-line cognitive testing to enhance the opportunity for identifying potentially eligible trial participants. Successful recruitment of patients meeting trial eligibility criteria from registries might require sharing genetic or biomarker risk information or cognitive testing results with participants. In addition to the legal and logistical challenges associated with such data sharing [19], another important consideration is whether those in the registry would be willing to learn disease risk information themselves or to have it shared with other researchers beyond those involved in the registry.

Registries that contain information viewed as sensitive and confidential frequently employ an “honest broker” model [20]. In this model, only de-identified data are shared with investigators querying the registry. A third party, not directly affiliated with the research (the so called “honest brokers”), contacts registrants to inform them of the study for which they might be eligible. The burden of establishing communication with the research team is thereby placed upon the potential participant. This model also presents the opportunity to keep the operators of the registry blinded to potentially sensitive information such as genetic testing outcomes, although in some cases the registry operators could also serve as the honest brokers. In contrast, other registries may permit investigators (with approval of an Institutional Review Board [IRB]) to directly access contact information for potentially eligible participants based on a registry query. In this “shared model,” researchers can directly establish communication with potentially eligible participants.

Although some studies suggest that potential participant registries are generally viewed as favorable among patients [20, 21] and researchers [22], few data are available to guide investigators initiating or conducting registries. Investigators need information on the barriers to enrolling potential participants in registries and the preferences these individuals have related to registry models and operations. To begin to provide such data, we administered a survey to a group of older cognitively normal research participants who represent the type of community-dwelling individuals who would be enrolled in potential participant registries with the aim of supporting recruitment to secondary AD prevention clinical trials.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

We mailed a survey packet to 110 participants in the UC Irvine AD Research Center (ADRC) longitudinal cohort study who met study inclusion criteria. The mailed packet included an explanatory cover-sheet, the paper survey instrument, a postage-paid return envelope, and a $2 bill as incentive to complete the study. The coversheet explained the rationale for the study, defined and described the purpose of potential participant registries, and requested that the participant complete the survey as if they were not currently enrolled in a research study. The survey was mailed to participants on August 13, 2015. Completed packets were received on or before November 12, 2015.

Participants

To be included, participants had to have completed an annual follow-up visit within the previous 18-months and received a consensus diagnosis of normal cognition. They had to be able to complete the survey in English and to have given permission to be contacted about other studies. One hundred and ten participants met criteria for this study, of which 74 (67%) returned completed surveys. The average age of this cohort was 75.2 ± 8.6 years at the time of survey dissemination, 71.2% were female, the mean level of education was 16.8 ± 2.6 years, 69.9% were non-Latino Caucasian, 24.0% were Asian, and the mean number of years as a participant in the UC Irvine ADRC was 9.0 ± 6.5 years.

Data collection

The survey included 39 items that addressed the topics of willingness to enroll in a registry, preferred models of registries, preferences regarding the return of results, and concerns about registry conduct. Most survey questions elicited responses on 6-point Likert scales and measured likelihood (i.e., “extremely unlikely” through “extremely likely”), willingness (i.e., “extremely unwilling” through “extremely willing”), level of agreement (i.e., “very much disagree” through “very much agree”), or level of concern (i.e., “not at all concerned” through “extremely concerned”), while others used a 5-point scale to assess relative likelihood (i.e., “much less likely” through “much more likely”). Some questions elicited responses via multiple choice (e.g., If you enrolled in a potential participants registry, which of the following would be your preferred method to let you know about studies for which you might be eligible?). A copy of the survey is available by emailing the corresponding author.

Statistical analyses

The distribution of responses for each survey item was quantified via empirical proportions. For items featuring a 6-point scale (e.g., “extremely unlikely,” “very unlikely,” “somewhat unlikely,” “somewhat likely,” “very likely,” “extremely likely”), we considered the proportion of responses within the two most positive response categories (e.g., the proportion who were “very” or “extremely willing” to enroll). For 5-point scales (e.g., “much less likely,” “somewhat less likely,” “no difference,” “somewhat more likely,” “much more likely”), we considered the proportion of responses that were “somewhat” and “much more likely.”

Sample proportions are presented with corresponding 95% Wald-based confidence intervals (CI). Within particular categories of survey questions (e.g., willingness to participate in registries operated through particular modalities), we tested for proportional equality across the responses to specific items using a bootstrapped version of the chi-square test. The test resampled survey responses under the null hypothesis of no difference in response distributions, thus accounting for the lack of independence across individual responses that the classical chi-square test assumes [23]. Adjustment for multiple comparisons in reported inference was performed using Holm’s procedure to produce adjusted p-values that maintain a familywise (two-sided) type I error rate of 0.05 across comparisons [23]. For comparison, unadjusted and adjusted p-values are presented side-by-side, adjusted p-values being marked with a dagger (‘†’). When adjusted and unadjusted p-values are equivalent, only unadjusted values are presented.

We used participant preferences for registry modality to assign them to one of three groups: honest broker, shared model, or no preference. We tested for homogeneity of concerns within preference groups and for item wise homogeneity across preference groups. For both tests, the quantity of interest was the proportion of the preference group that was moderately or extremely concerned. Within preference groups, we tested for homogeneity of concerns for unwanted communication and inappropriate sharing of health information separately, but using the same bootstrapped chi-square test. A p-value < 0.05 corresponds to evidence for non-homogeneity of concerns. We used a classical chi-square test to examine whether levels of concern differed across preference groups.

Statistical computations were performed using the R programming language, the ‘boot’ package for bootstrapping [24], and ‘ggplot2’ for producing bar graphs [25].

Ethics

This study was approved by the UC Irvine Institutional Review Board. A waiver of signed informed consent was granted; returned completed surveys were considered a demonstration of consent to participate.

RESULTS

Sample

This anonymous survey was administered only to cognitively normal participants in the UC Irvine ADRC. In general, these participants are age 65 or older. All are willing to participate in annual neurological and physical exams, blood draws (including apolipoprotein E genotyping at first visit, the results of which are not disclosed to participants), and a battery of neuropsychological tests.

Willingness to enroll in registries

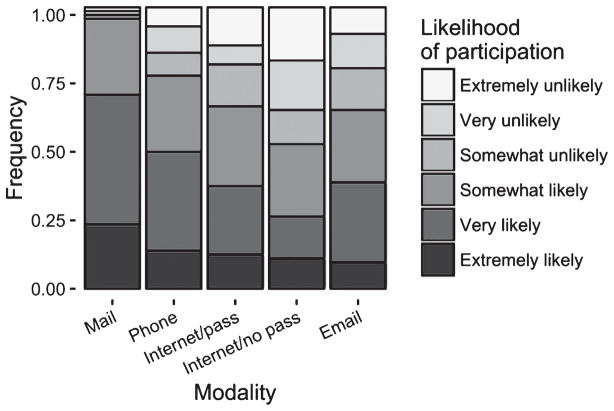

Seventy-eight percent of respondents (CI: 0.67, 0.87) stated that they were very or extremely likely to enroll in a registry. When we asked about specific registry operations, 69% (CI: 0.58, 0.80) of respondents were likely to enroll in a registry by mail (Fig. 1). The proportions of respondents who were likely to enroll were reduced for the remaining modalities of registries (49% (CI: 0.37, 0.60) for telephone, 38% for email (CI: 0.27, 0.49), 37% for Internet (CI: 0.26, 0.48), 26% (CI: 0.16, 0.36) for Internet requiring a username and password; bootstrapped chi-square test, p < 0.01 for all comparisons).

Fig. 1.

Respondent willingness to enroll in registry modalities. The frequency of participant responses related to the willingness to enroll for each of five potential participant registry operation modalities is displayed. Modalities include mail, telephone (phone), Internet without password requirement (Internet/no pass), Internet with a password requirement (Internet/pass), and email.

A large majority (85%; CI: 0.75, 0.91) of respondents were willing to spend 30 minutes or longer enrolling in a potential participants registry. Nearly half (49%; CI: 0.37, 0.60) were willing to spend 60 minutes or longer. Fifteen percent (CI: 0.08, 0.25) responded that they would be willing to spend no more than 15 minutes engaged in the process of enrolling in a registry.

Most participants were willing to receive contact more than once per year about studies for which they might be eligible and 30% responded that there was no limit to the number of times they would be willing to be contacted (Table 1). Eighty-eight percent (CI: 0.78, 0.94) of respondents reported that they would be willing to renew their participation year after year until they were matched to a study.

Table 1.

Respondent willingness to be contacted about new studies

| Number of times respondents are willing to be contacted a year | Proportion | 95% Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| Once every other year | 0.03 | (0.00, 0.10) |

| One | 0.11 | (0.04, 0.18) |

| Two to three | 0.37 | (0.26, 0.49) |

| Four to five | 0.14 | (0.07, 0.24) |

| Six to ten | 0.07 | (0.01, 0.13) |

| Unlimited | 0.30 | (0.20, 0.40) |

Table 2 describes the proportion of participants who were willing to have personal information included in the registry for the purpose of being matched to studies. A majority of respondents were willing to include demographic, lifestyle, and medical information. Similarly, most participants were agreeable to providing buccal swabs for genetic testing, undergoing in-clinic cognitive testing or blood draw for genetic testing, and to having their electronic medical records linked to a registry. In contrast, 47% of participants were willing to take cognitive tests at home on the Internet as part of a registry, a lower proportion than for all other methods of identifying potentially eligible participants that we examined (bootstrapped chi-square, p = 0.02, 0.20†).

Table 2.

Respondent willingness to contribute personal information for the purpose of being matched to studies

| Type of information | Proportion | 95% Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic | 0.89 | (0.82, 0.96) |

| Lifestyle information | 0.88 | (0.78, 0.94) |

| Medical information | 0.77 | (0.66, 0.86) |

| Buccal swabs for genetic testing | 0.76 | (0.64, 0.85) |

| In-clinic cognitive testing | 0.76 | (0.64, 0.85) |

| Linking electronic medical records | 0.68 | (0.57, 0.78) |

| In-clinic blood draw for genetic testing | 0.62 | (0.49, 0.72) |

| In-home cognitive testing | 0.47 | (0.36, 0.59) |

Respondents indicated that a variety of incentives had the potential to impact their decision whether to enroll in a registry. Receiving health information based on on-going research would have made 84% (CI: 0.75, 0.92) of respondents more likely to enroll, but if that information was specific to brain health, the proportion increased to 91% (CI: 0.84, 0.97). Similarly high proportions of respondents indicated that receiving personal research results from cognitive tests (87%; CI: 0.79, 0.94), genetic tests (80%; CI: 0.71, 0.89), and standard laboratories (77%; CI: 0.67, 0.87) would increase willingness to enroll. In contrast, only 45% (CI: 0.33, 0.56) of respondents reported that financial incentives would make them more likely to enroll.

Returning health findings

Ninety-five percent (CI: 0.86, 0.98) of respondents agreed that if researchers discovered new information about their health through the course of collecting registry information, they would expect to be informed of those discoveries. Ninety-eight percent (CI: 0.92, 1) reported that they would want this information. When asked whether they would expect researchers to share disease risk information with them, if it were discovered, 89% (CI: 0.79, 0.95) agreed that this was an expectation and 95% (CI: 0.86, 0.98) indicated that they would want this information.

Concerns

We asked participants to assess the level to which they would have concerns about seven aspects of registry operations (Fig. 2). Concern was greatest for the potential sharing of information with pharmaceutical companies (70%; CI: 0.60, 0.81) and with insurance companies (66%; CI: 0.55, 0.77). Sixty-one percent (CI: 0.50, 0.72), 62% (CI: 0.51, 0.73), and 51% (CI: 0.40, 0.63) of respondents were concerned about receiving unwanted telephone contact, electronic communication, and mail contact, respectively. Forty-one percent (CI: 0.29, 0.52) of participants reported that they would be concerned about possible inappropriate sharing of their information with doctors outside of the (UC Irvine) healthcare system and 28% (CI: 0.18, 0.39) were concerned about inappropriate sharing within the healthcare system. Only 14% (CI: 0.06, 0.21) of participants indicated that, if they enrolled in the registry, they would only want to be contacted about studies related to AD.

Fig. 2.

Respondent levels of concern. The proportion of respondents who indicated each level of concern is illustrated for each of seven areas related to registry operations: sharing registrant information with pharmaceutical companies (“Sharing with pharma”), sharing registrant information with insurance companies (“Sharing with insurance”), unwanted phone calls (“Unwanted phone calls”), unwanted email (“Unwanted email”), sharing registrant information with healthcare professionals outside of the healthcare system (“Sharing with outside doctors”), unwanted mail communication (“Unwanted mail”), and sharing registrant information with health-care professionals within the healthcare system (“Sharing within healthcare”).

Models of registries

We asked participants how likely they would be to enroll in two models of registry function. Forty-two percent (CI: 0.31, 0.54) of participants reported that they were likely to enroll in a shared information registry, while 55% (CI: 0.43, 0.67) of participants reported that they were likely to enroll in an honest broker model. When asked if they had a preferred model of registry, 30% (CI: 0.20, 0.42) reported preferring the honest broker model, 28% (CI: 0.19, 0.40) reported preferring the shared information model, and 42% (CI: 0.31, 0.53) reported having no preference. There was no difference in the proportions of respondents preferring the shared information compared to honest broker models (p = 0.46, 1.00†). Table 3 presents participant concerns based on their registry modality preference. The groups that preferred the honest broker modality and that had no preference were not uniformly concerned about different kinds of inappropriate sharing of health information (p < 0.01). Specifically, these groups tended to be more concerned about sharing with for-profit and insurance companies than about sharing with doctors within and outside of the healthcare system. Those preferring the shared model demonstrated relatively uniform levels of concern across the investigated areas. Differences in levels of concern between the groups based on stated preferred models did not reach significance in adjusted statistical tests.

Table 3.

Proportion of respondents who were moderately or extremely concerned, based on preferences for registry modalities

| Area of concern | Honest Broker (n = 22) | Shared model (n = 21) | No preference (n = 31) | Itemwise comparison, unadjusted p-value, adjusted p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unwanted communication, test of homogeneity unadjusted p-value, adjusted p-value | p = 0.31, 1.00† | p = 0.11, 0.88† | p = 0.14, 0.91† | |

| Telephone, proportion | 0.73 | 0.48 | 0.61 | 0.08, 0.72† |

| Mail, proportion | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.42, 1.00† |

| Email, proportion | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.96, 1.00† |

| Inappropriate sharing of health information, test of homogeneity unadjusted p value, adjusted p value | p < 0.01 | p = 0.06, 0.66† | p < 0.01 | |

| Doctors within the healthcare system, proportion | 0.21 | 0.33 | 0.19 | 0.06, 0.66† |

| Doctors outside of the healthcare system, proportion | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.16, 0.91† |

| Insurance companies, proportion | 0.73 | 0.52 | 0.71 | 0.13, 0.91† |

| For-profit companies, proportion | 0.86 | 0.52 | 0.71 | 0.02, 0.24† |

DISCUSSION

These results suggest that willingness to enroll in potential participant registries is high. We found that older adults in our study were more willing to enroll by mail than by any other modality. This result suggests that Internet- and e-mail-based registries, which are likely to be needed to achieve the large sample sizes necessary to adequately recruit to primary and secondary AD prevention trials, may face challenges in enrolling adequate populations. Investigators may need to consider mixed methodologies, combining modern electronic methods with traditional mail and telephone methods to maximize enrollment of older volunteers.

Our survey also indicates that, once enrolled, potential participants are eager to be matched to studies and to provide investigators with additional information to assist in this process. Participants responded with high frequency that they were willing to provide demographic, lifestyle, and medical information, including giving researchers access to their medical records. They were also willing to come to the clinic to donate blood for genetic testing or to undergo cognitive testing. Strikingly, willingness was sizably reduced for performing cognitive testing at home on the Internet as a means for being matched to studies. This finding is similar to results from the AD Cooperative Study Home Based Assessment study, which aimed to examine optimal methods for long-term monitoring of AD prevention trial participants. In that study the greatest dropout from screen to baseline was observed in a group that was randomly assigned to receive a computer kiosk for the purpose of in-home cognitive testing [26]. Our results suggest that this reluctance may have resulted from other factors beyond the inconvenience of placing a kiosk in the home.

We examined whether a variety of incentives could affect the decision whether to enroll in a potential participants registry. Similar to a previous examination of potential incentives for enrollment in AD prevention trials [27], we found that opportunities to receive personal research results were the most effective incentives to enrollment and that financial compensation was least effective. Nearly all participants also agreed that if researchers discovered new information about their health through the course of collecting registry information, they would expect to be informed of those discoveries. Returning research results to participants during a study can bring unwanted complications to protocols, including the need for Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments certification for genetic tests [19] and the potential for stereotype threat [28]. Nevertheless, the increasing consistency with which returning research results has been identified as an incentive to participation and the growing voice in the field that participants should be treated as equal partners in the research enterprise [29] suggest that investigators must consider new means to involve participants in research.

Participants endorsed a variety of concerns about registry participation that appeared to differ, based on the preferred model of registry operations. Compared to those with a preference for a shared model, those with a stated preference for an honest broker operational model voiced stronger concerns over the potential to receive unwanted contact about studies, as well as concerns about the potential for inappropriate sharing of their information, especially with insurance and pharmaceutical companies. These observations suggest that the design of a registry could impact the population that ultimately enrolls and could have important scientific implications to trial recruitment using potential participant registries.

Our study has several limitations. While there is the potential for non-response bias, we did observe a relatively high 67% response rate. This may be due to the fact that a population that is already engaged in clinical research completed the survey. These participants may have positive attitudes toward research, though we did not explicitly measure such attitudes, and they may therefore be more likely than the general public to be willing to join a registry and to spend longer periods of time registering. It is in fact possible that some of our participants have previously enrolled in a registry; our survey did not address this. These participants have enrolled in a study of cognitive aging, which may be particularly relevant to questions about potential incentives for enrolling in a registry, such as receiving cognitive testing results or information on brain health. Furthermore, the study in which those who completed the survey are enrolled involves in-person annual cognitive testing, suggesting that responses related to in-person versus on-line cognitive testing may have been specific to this sample. Finally, the UCI ADRC cognitively normal cohort is composed primarily of Caucasian and Chinese-American English-speakers. Although this remains understudied, registries may represent an important intervention to enhance the diversity of trial samples [12] and our data may not translate to racially and ethnically diverse communities. Though these findings may be important to investigators considering developing potential participant registries for the purpose of recruiting to AD prevention trials, they may be less pertinent to other areas of clinical research and need replication in community cohorts.

Conclusions

This study finds that older healthy people who have research experience are willing to enroll in potential participant registries and to provide data to assist in matching them to studies. Preferences among those in our study were for mail-based registries. A high proportion of participants were willing to attend clinic visits for the purpose of providing researchers additional data for matching them to studies. Respondents’ greatest concerns related to the potential for registry data to be shared with for-profit organizations. This concern was greatest for participants who preferred the honest broker model of registry. Overall, our results suggest that, while registries may represent an important and effective means to facilitate clinical research recruitment, the model and methods of the registry may affect the population enrolled.

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible by a donation from HCP, Inc. Dr. Grill, Mr. Holbrook, Dr. Pierce, Mr. Hoang, and Dr. Gillen were supported by NIA AG016573. Dr. Grill was supported by UL1 TR000153. The authors wish to thank the participants who completed the survey.

Authors’ disclosures available online (http://j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/16-0873r1).

References

- 1.Kasenda B, von Elm E, You J, Blumle A, Tomonaga Y, Saccilotto R, Amstutz A, Bengough T, Meerpohl JJ, Stegert M, Tikkinen KA, Neumann I, Carrasco-Labra A, Faulhaber M, Mulla SM, Mertz D, Akl EA, Bassler D, Busse JW, Ferreira-González I, Lamontagne F, Nordmann A, Gloy V, Raatz H, Moja L, Rosenthal R, Ebrahim S, Schandelmaier S, Xin S, Vandvik PO, Johnston BC, Walter MA, Burnand B, Schwenkglenks M, Hemkens LG, Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Briel M. Prevalence, characteristics, and publication of discontinued randomized trials. JAMA. 2014;311:1045–1051. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vellas B, Pesce A, Robert PH, Aisen PS, Ancoli-Israel S, Andrieu S, Cedarbaum J, Dubois B, Siemers E, Spire JP, Weiner MW, May TS. AMPA workshop on challenges faced by investigators conducting Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:e109–e117. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.05.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grill JD, Karlawish J. Addressing the challenges to successful recruitment and retention in Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2010;2:34. doi: 10.1186/alzrt58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:332–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rafii MS. Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease therapeutics. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42(Suppl 4):S545–S549. doi: 10.3233/JAD-141482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider LS. Recruitment methods for United States Alzheimer disease prevention trials. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16:331–335. doi: 10.1007/s12603-012-0011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sperling RA, Jack CR, Jr, Aisen PS. Testing the right target and right drug at the right stage. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:111–133. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grill JD, Monsell SE. Choosing Alzheimer’s disease prevention clinical trial populations. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:466–471. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grill JD, Galvin JE. Facilitating Alzheimer disease research recruitment. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2014;28:1–8. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bristol-Gould S, Desjardins M, Woodruff TK. The Illinois Women’s Health Registry: Advancing women’s health research and education in Illinois, USA. Womens Health (Lond) 2010;6:183–196. doi: 10.2217/whe.10.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris PA, Scott KW, Lebo L, Hassan N, Lightner C, Pulley J. ResearchMatch: A national registry to recruit volunteers for clinical research. Acad Med. 2012;87:66–73. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823ab7d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romero HR, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Gwyther LP, Edmonds HL, Plassman BL, Germain CM, McCart M, Hayden KM, Pieper C, Roses AD. Community engagement in diverse populations for Alzheimer disease prevention trials. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2014;28:269–274. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saunders KT, Langbaum JB, Holt CJ, Chen W, High N, Langlois C, Sabbagh M, Tariot PN. Arizona Alzheimer’s Registry: Strategy and outcomes of a statewide research recruitment registry. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2014;1:74–79. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2014.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petersen RC, Nixon RA, Thies W, Taylor A, Geiger AT, Cordell C. Alzheimer’s Association TrialMatch: A next generation resource for matching patients to clinical trials in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2012;2:105–113. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reiman EM, Langbaum JB, Fleisher AS, Caselli RJ, Chen K, Ayutyanont N, Quiroz YT, Kosik KS, Lopera F, Tariot PN. Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative: A plan to accelerate the evaluation of presymptomatic treatments. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;26(Suppl 3):321–329. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reiman EM, Langbaum JB, Tariot PN. Alzheimer’s prevention initiative: A proposal to evaluate presymptomatic treatments as quickly as possible. Biomark Med. 2010;4:3–14. doi: 10.2217/bmm.09.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aisen P, Touchon J, Andrieu S, Boada M, Doody RS, Nosheny RL, Langbaum JB, Schneider L, Hendrix S, Wilcock G, Molinuevo JL, Ritchie C, Ousset P-J, Cummings J, Sperling R, DeKosky ST, Lovestone S, Hampel H, Petersen R, Legrand V, Egan M, Randolph C, Salloway S, Weiner M, Vellas B Task Force Members. Registries and cohorts to accelerate early phase Alzheimer’s trials. A report from the E.U./U.S. Clinical Trials in Alzheimer’s Disease Task Force. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2016;3:7. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2016.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sager MA, Hermann B, La Rue A. Middle-aged children of persons with Alzheimer’s disease: APOE genotypes and cognitive function in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2005;18:245–249. doi: 10.1177/0891988705281882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Research Council. Issues in Returning Individual Results from Genome Research Using Population-Based Banked Specimens, with a Focus on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Workshop Summary. Issues in Returning Individual Results from Genome Research Using Population-Based Banked Specimens, with a Focus on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: A Workshop Summary. In: Kinsella K, editor. Steering Committee for the Workshop on Guidelines for Returning Individual Results from Genome Research Using Population-Based Banked Specimens, Committee on National Statistics, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Callard F, Broadbent M, Denis M, Hotopf M, Soncul M, Wykes T, Lovestone S, Stewart R. Developing a new model for patient recruitment in mental health services: A cohort study using Electronic Health Records. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005654. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robotham D, Riches S, Perdue I, Callard F, Craig T, Rose D, Wykes T. Consenting for contact? Linking electronic health records to a research register within psychosis services, a mixed method study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:199. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0858-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papoulias C, Robotham D, Drake G, Rose D, Wykes T. Staff and service users’ views on a ‘Consent for Contact’ research register within psychosis services: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:377. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0377-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat. 1979;6:6. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Canty A, Ripley B. R package version 1.3-17. 2015. boot: Bootstrap R (S-Plus) Functions. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wickham H. ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sano M, Egelko S, Donohue M, Ferris S, Kaye J, Hayes TL, Mundt JC, Sun CK, Paparello S, Aisen PS Alzheimer Disease Cooperative Study Investigators. Developing dementia prevention trials: Baseline report of the Home-Based Assessment study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2013;27:356–362. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3182769c05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grill JD, Zhou Y, Elashoff D, Karlawish J. Disclosure of amyloid status is not a barrier to recruitment in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;39:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lineweaver TT, Bondi MW, Galasko D, Salmon DP. Effect of knowledge of APOE genotype on subjective and objective memory performance in healthy older adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:201–208. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12121590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chakradhar S. Many returns: Call-ins and breakfasts hand back results to study volunteers. Nat Med. 2015;21:304–306. doi: 10.1038/nm0415-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]