Abstract

Objective

Diverticulitis is a common disease with a substantial clinical and economic burden. Besides dietary fiber, the role of other foods in the prevention of diverticulitis is underexplored.

Design

We prospectively examined the association between consumption of meat (total red meat, red unprocessed meat, red processed meat, poultry and fish) with risk of incident diverticulitis among 46,461 men enrolled in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (1986–2012). Cox proportional hazards models were used to compute relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

During 651,970 person-years of follow-up, we documented 764 cases of incident diverticulitis. Compared to men in the lowest quintile (Q1) of total red meat consumption, men in the highest quintile (Q5) had a multivariable RR of 1.58 (95% CI: 1.19, 2.11; P for trend=0.01). The increase in risk was non-linear, plateauing after 6 servings per week (P for non-linearity=0.002). The association was stronger for unprocessed red meat (RR for Q5 vs Q1: 1.51; 95% CI: 1.12, 2.03; P for trend=0.03) than for processed red meat (RR for Q5 vs Q1: 1.03; 95% CI: 0.78, 1.35; P for trend=0.26). Higher consumption of poultry/fish was not associated with risk of diverticulitis. However, the substitution of poultry/fish for one serving of unprocessed red meat per day was associated with a decrease in risk of diverticulitis (multivariable RR 0.80; 95% CI: 0.63, 0.99).

Conclusion

Red meat intake, particularly unprocessed red meat, was associated with an increased risk of diverticulitis. The findings provide practical dietary guidance for patients at risk of diverticulitis.

Keywords: diverticular disease, epidemiology, dietary factors

INTRODUCTION

Diverticulitis is the inflammation of diverticula of the colon. It is a common disease that results in about 210,000 hospitalizations per year in the U.S. at a cost of more than 2 billion dollars.1 Recently, the incidence of diverticulitis has been rising, particularly in young individuals.2,3 Approximately 4% of patients with diverticula develop acute or chronic complications including perforation, abscess, and fistula.4 Despite the enormous clinical and economic burden of diverticulitis, little is known about its epidemiology and etiopathogenesis.5 Although smoking,6,7 non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs),8 physical inactivity and obesity9–11 are identified as risk factors for diverticulitis, dietary factors are less explored.

Dietary fiber is the most studied dietary risk factor for diverticular disease. However, a few studies suggest that red meat consumption may also be important.12,13 A recent prospective UK population-based cohort study found that risk of diverticular disease was 31% lower among vegetarians or vegans (relative risk [RR]: 0.69; 95% CI: 0.55, 0.86) compared to meat eaters.13 However, the endpoint of the study was diverticular disease that required hospitalization, and therefore the results may not be generalizable to patients with more common and mild presentations of diverticulitis.1 In addition, the specific contribution of red meat, poultry or fish to the observed link was not investigated.

In our prior analysis from a large prospective cohort study, the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS), we found that red meat intake, independent of fiber, may be associated with a composite outcome of symptomatic diverticular disease which included 385 incident cases over 4 years of follow-up.12. Diverticulitis is distinct in presentation, treatment and pathophysiology from other manifestations of diverticular disease including uncomplicated diverticulosis and diverticular bleeding.5 Thus, in the present study, we updated this analysis, which allowed us to prospectively examine the association between consumption of meat (total red meat, red unprocessed meat, red processed meat, poultry and fish) with risk of incident diverticulitis in 764 cases over 26 years of follow-up.

METHODS

Study population

The HPFS is a large ongoing prospective cohort study of 51,529 U.S. male health professionals aged 40–75 years at enrollment in 1986. Participants have been mailed questionnaires every 2 years since baseline to collect data on demographics, lifestyle factors, medical history, and disease outcomes, and every 4 years to update dietary intake. The overall follow-up rate is greater than 94%.14 This study was approved by the institutional review board at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

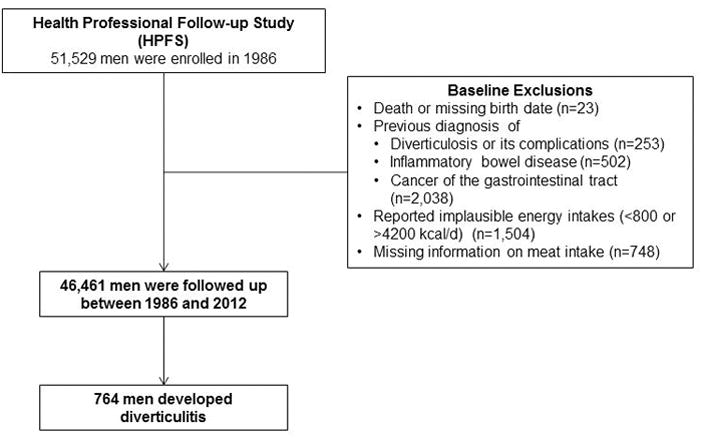

Men who reported a diagnosis of diverticulosis or its complications (n=253), inflammatory bowel disease (n=502), or a cancer of the gastrointestinal tract (n=2,038) at baseline in 1986 were excluded from the analysis (Figure 1). In addition, we excluded study participants who reported implausible energy intakes (<800 or >4200 kcal/d) (n=1,504), and who did not answer questions regarding intake of unprocessed and processed meat, poultry and fish (n=748). A total of 46,461 men were included in the current analysis.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study population.

Assessment of meat intake

Participants in the HPFS completed semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaires (FFQ) in 1986 which was updated every four years. In each FFQ, we asked the participants how often, on average, they consumed each food of a standard portion size during the past year. There were 9 possible responses, ranging from “never or less than once per month” to “6 or more times per day”. For unprocessed red meat consumption, the FFQ included questions on “beef or lamb as main dish”; “pork as main dish”; “hamburger”; and “beef, pork, or lamb as a sandwich or mixed dish”. For processed red meat, there were questions on “bacon”; “beef or pork hot dogs”; “salami, bologna, or other processed meat sandwiches” and “other processed red meats such as sausage, kielbasa, etc.”. We derived total red meat consumption by summing consumption of unprocessed and processed red meat. For total poultry consumption, the FFQ included questions on “chicken or turkey with or without skin”; “chicken or turkey hot dogs”; and “chicken or turkey sandwiches”. For total fish intake, consumption of “dark meat fish”; “canned tuna fish”; “breaded fish cakes, pieces, or fish sticks”; and “other fish” were added up. The reproducibility and validity of the FFQs in measuring food intake have been previously described.15,16

Ascertainment of diverticulitis cases

The primary endpoint of this study was incident diverticulitis. Beginning in 1990, participants who reported newly diagnosed diverticulitis or diverticulosis on the biennial study questionnaire were sent supplementary questionnaires that ascertained the date of diagnosis, presenting symptoms, diagnostic procedures and treatment. Diverticulitis was defined as abdominal pain attributed to diverticular disease and one of the following criteria: 1) complicated by perforation, abscess, fistula, or obstruction; 2) requiring hospitalization, antibiotics, or surgery; or 3) pain categorized as severe or acute; or abdominal pain presenting with fever, requiring medication, or evaluated using abdominal computed tomography. We have previously used these case definitions and documented the validity of self-reported diverticulitis in this population.10,11,17

Beginning in 2006, we administered a revised supplementary diverticular disease questionnaire. Using questions that included definitions for each disease outcome, we assessed uncomplicated diverticulitis, complications of diverticulitis including abscess, fistula, perforation and obstruction, diverticular bleeding and diverticulosis.8

Statistical Analysis

In our primary analyses, we examined the association between consumption of meat (total red meat, red unprocessed meat, red processed meat, poultry and fish) with risk of incident diverticulitis. Person-years of follow-up accrued from the date of return of the 1986 questionnaire until either the date of diagnosis of diverticulitis, diverticulosis or diverticular bleeding, death or December 31, 2012, whichever came first. We censored men who reported a new diagnosis of gastrointestinal cancer or inflammatory bowel disease.

Cox proportional hazards models with time-varying meat consumption and covariates were used to compute hazard ratios as estimates for age-adjusted and multivariable-adjusted relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). To control as finely as possible for confounding by age, calendar time, and a possible interaction between these two time scales, we stratified models jointly by age (in months) and 2-year questionnaire cycle. In age-adjusted models, we additionally adjusted for total energy intake. In multivariable models, we further adjusted for the following potential confounders: body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2 in quintiles), vigorous physical activity including activities with a metabolic equivalent task (MET) score of 6 or more (MET-hrs/wk in quintiles), smoking history (never smokers, <4.9, 5–19.9, 20–39.9, ≥40 pack years), fiber intake (g/d in quintiles), regular use of aspirin, non-aspirin NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), and acetaminophen (≥2 vs <2 times/wk). We updated meat consumption as well as other covariates prior to each two/four-year interval (simple updating).

Tests for linear trend were performed using meat consumption as a continuous variable. We examined the possible non-linear relation between meat consumption and risk of diverticulitis non-parametrically with restricted cubic splines.18–20 To test for non-linearity, we used a likelihood ratio test, comparing the model with only the linear term to the model with the linear and the cubic spline terms. Departures from the proportional hazards assumption were tested by likelihood ratio tests comparing models with and without the interaction terms of age or calendar time by categories of meat consumption. No significant violation of the proportionality assumption was found (P>0.05 for all tests).

As an exploratory analysis, we assessed the association between components of red meat including total fat, saturated fat, cholesterol and heme iron and incident diverticulitis, with and without additionally adjusting for unprocessed and processed red meat. To facilitate the translation to dietary recommendations regarding meat intake, we estimated the associations of substituting one serving of poultry or fish for one serving of red meat with incident diverticulitis by including both as continuous variables in the same multivariate model. The difference in their beta coefficients, as well as their variances and covariance were used to estimate the RR and 95% CI for the substitution associations.21,22 All of the analyses were performed using SAS v 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and the statistical tests were two-sided and P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

During 651,970 person years of follow-up, we documented 764 incident cases of diverticulitis. Compared with men with lower intake of red meat, men with higher red meat consumption smoked more, used non-aspirin NSAIDs and acetaminophen more often, and were less likely to exercise vigorously (Table 1). As expected, their intake of total fat, saturated fat, cholesterol and heme iron were substantially higher. In contrast, fiber intake among these men was lower. Compared with men with lower poultry/fish consumption, men with higher poultry/fish consumption were more likely to be engaged in vigorous physical activity, use aspirin, smoke less, and had higher intake of heme iron. Men with higher poultry intake also had higher intake of cholesterol, and individuals with higher fish intake had lower intake of total and saturated fat.

Table 1.

Characteristics according to person-years of meat intake consumption, HPFS 1986–2012

| Characteristic | Meat intake, quintile | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Total red meat | Unprocessed meat | Processed meat | Poultry | Fish | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 5 | |

| Meat intake, servings/wk | 1.2 | 5.3 | 13.5 | 0.8 | 3.2 | 8.6 | 0 | 1.4 | 6.4 | 0.7 | 2.7 | 6.2 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 2.5 |

| Age, yrs* | 63 | 62 | 62 | 64 | 62 | 61 | 63 | 62 | 62 | 65 | 62 | 60 | 62 | 61 | 63 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 25 | 26 | 26 | 25 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 |

| Vigorous physical activity, MET-hrs/wk | 18 | 12 | 9 | 18 | 12 | 9 | 17 | 12 | 9 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 10 | 12 | 14 |

| Ever smokers, % | 46 | 51 | 55 | 47 | 52 | 52 | 44 | 51 | 56 | 51 | 51 | 49 | 49 | 51 | 51 |

| Pack-year among ever smokers | 21 | 24 | 28 | 22 | 25 | 27 | 21 | 24 | 28 | 26 | 24 | 23 | 27 | 25 | 23 |

| Alcohol intake, g/d | 8.8 | 12 | 13 | 9 | 12 | 13 | 8.7 | 12 | 14 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 12 | 12 |

| Dietary fiber, g/d | 28 | 22 | 20 | 27 | 22 | 20 | 28 | 22 | 20 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 21 | 22 | 24 |

| Total fat, g/d | 58 | 70 | 78 | 60 | 70 | 77 | 59 | 70 | 77 | 70 | 68 | 68 | 72 | 70 | 68 |

| Saturated fat, g/d | 17 | 23 | 27 | 18 | 23 | 26 | 18 | 23 | 26 | 23 | 22 | 21 | 25 | 23 | 22 |

| Cholesterol, mg/d | 213 | 267 | 320 | 219 | 268 | 313 | 217 | 266 | 312 | 238 | 263 | 293 | 257 | 269 | 266 |

| Heme iron, mg/d | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Regular aspirin use, % | 47 | 46 | 45 | 47 | 47 | 46 | 47 | 47 | 45 | 44 | 47 | 48 | 44 | 45 | 49 |

| Regular non-aspirin NSAID use, % | 12 | 15 | 16 | 12 | 15 | 16 | 12 | 15 | 15 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 14 |

| Regular acetaminophen use, % | 6.6 | 8.3 | 9.4 | 6.8 | 8.2 | 9.3 | 6.4 | 8.1 | 9.2 | 7.3 | 7.9 | 8.8 | 8.5 | 8.1 | 8.3 |

All values other than age have been directly standardized to age distribution (in 5-year age group) of all the participants. Mean was presented for continuous variables.

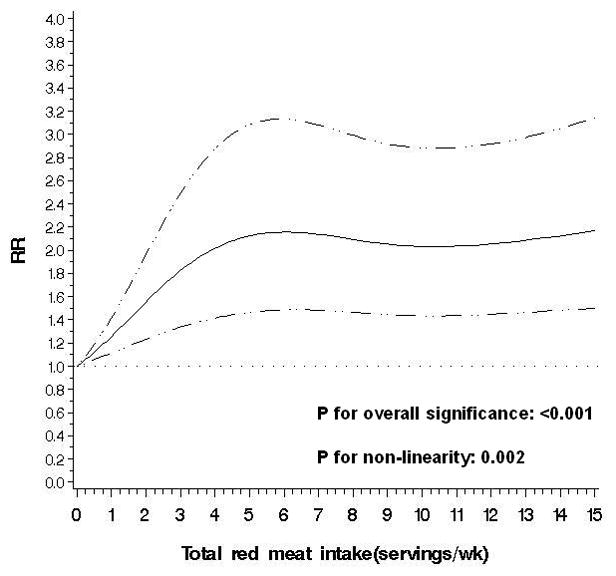

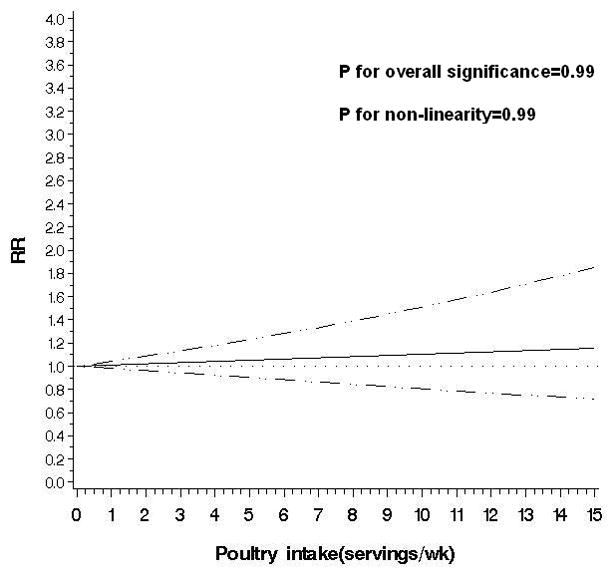

Overall, total red meat intake was associated with an increased risk of diverticulitis. Compared to men in the lowest quintile of total red meat consumption, men in the highest quintile had a multivariable RR of 1.58 (95% CI: 1.19, 2.11) (Table 2) after adjustment for total fiber and all other potential confounding variables. The risk of incident diverticulitis increased 18% per serving of red meat consumed per day (P for trend=0.01). Nonparametric regression curves suggest that the dose-response relationship for total red meat was non-linear (P for non-linearity=0.002): even 1 serving per week appeared to increase risk, with risk plateauing after 6 servings per week (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Meat consumption and risk of incident diverticulitis

| Meat consumption, quintile | per 1 serving/d | P for trend* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| Total red meat | |||||||

| Cases, No. | 106 | 158 | 164 | 153 | 183 | ||

| Person-years | 134819 | 128596 | 128853 | 127720 | 131982 | ||

| Median intake, servings/wk | 1.5 | 3.4 | 5.4 | 7.9 | 12.4 | ||

| Age-adjusted RR (95% CI)† | 1[Reference] | 1.56 (1.22, 2.01) | 1.69 (1.32, 2.18) | 1.67 (1.29, 2.16) | 2.09 (1.60, 2.71) | 1.33 (1.19, 1.48) | <0.001 |

| Multivariable RR (95% CI)‡ | 1[Reference] | 1.39 (1.08, 1.80) | 1.43 (1.10, 1.85) | 1.35 (1.02, 1.77) | 1.58 (1.19, 2.11) | 1.18 (1.04, 1.33) | 0.01 |

| Unprocessed red meat | |||||||

| Cases, No. | 99 | 148 | 189 | 162 | 166 | ||

| Person-years | 135137 | 121492 | 136654 | 126194 | 132493 | ||

| Median intake, servings/wk | 0.98 | 2.0 | 2.9 | 5.0 | 8.0 | ||

| Age-adjusted RR (95% CI)† | 1[Reference] | 1.63 (1.26, 2.11) | 1.90 (1.48, 2.44) | 1.85 (1.42, 2.39) | 1.95 (1.49, 2.55) | 1.48 (1.26, 1.75) | <0.001 |

| Multivariable RR (95% CI)‡ | 1[Reference] | 1.46 (1.12, 1.90) | 1.63 (1.26, 2.11) | 1.52 (1.16, 1.99) | 1.54 (1.16, 2.05) | 1.26 (1.05, 1.51) | 0.01 |

| Multivariable RR (95% CI)§ | 1[Reference] | 1.47 (1.12, 1.93) | 1.61 (1.23, 2.10) | 1.49 (1.13, 1.98) | 1.51 (1.12, 2.03) | 1.23 (1.02, 1.49) | 0.03 |

| Processed red meat | |||||||

| Cases, No. | 116 | 130 | 184 | 165 | 169 | ||

| Person-years | 120357 | 127492 | 155568 | 118180 | 130373 | ||

| Median intake, servings/wk | 0 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 5.5 | ||

| Age-adjusted RR (95% CI)† | 1[Reference] | 1.12 (0.87, 1.45) | 1.26 (1.00, 1.60) | 1.54 (1.21, 1.97) | 1.49 (1.16, 1.91) | 1.35 (1.14, 1.58) | <0.001 |

| Multivariable RR (95% CI)‡ | 1[Reference] | 1.00 (0.77, 1.30) | 1.05 (0.83, 1.35) | 1.23 (0.95, 1.59) | 1.13 (0.87, 1.48) | 1.15 (0.96, 1.38) | 0.14 |

| Multivariable RR (95% CI)§ | 1[Reference] | 0.95 (0.73, 1.23) | 0.95 (0.74, 1.23) | 1.10 (0.84, 1.43) | 1.03 (0.78, 1.35) | 1.11 (0.92, 1.35) | 0.26 |

| Poultry | |||||||

| Cases, No. | 145 | 160 | 186 | 127 | 146 | ||

| Person-years | 130083 | 137482 | 129756 | 115726 | 138924 | ||

| Median intake, servings/wk | 1.0 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 6.0 | ||

| Age-adjusted RR (95% CI)† | 1[Reference] | 1.15 (0.91, 1.45) | 1.30 (1.04, 1.63) | 1.08 (0.84, 1.38) | 1.05 (0.83, 1.34) | 1.03 (0.82, 1.28) | 0.83 |

| Multivariable RR (95% CI)‡ | 1[Reference] | 1.13 (0.89, 1.43) | 1.33 (1.06, 1.66) | 1.13 (0.88, 1.45) | 1.09 (0.86, 1.39) | 1.07 (0.86, 1.33) | 0.55 |

| Fish | |||||||

| Cases, No. | 159 | 152 | 173 | 141 | 139 | ||

| Person-years | 117176 | 113430 | 163700 | 122327 | 135337 | ||

| Median intake, servings/wk | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 4.5 | ||

| Age-adjusted RR (95% CI)† | 1[Reference] | 1.01 (0.80, 1.26) | 0.82 (0.66, 1.03) | 0.83 (0.66, 1.05) | 0.76 (0.60, 0.97) | 0.69 (0.51, 0.93) | 0.01 |

| Multivariable RR (95% CI)‡ | 1[Reference] | 1.03 (0.82, 1.29) | 0.86 (0.69, 1.08) | 0.90 (0.71, 1.14) | 0.87 (0.68, 1.10) | 0.82 (0.61, 1.11) | 0.20 |

Calculated using continuous meat intake.

Adjusted for age, questionnaire cycle and total energy intake (quintiles).

Additionally adjusted for BMI (quintiles), vigorous physical activity (quintiles), smoking history (never smokers, <4.9, 5–19.9, 20–39.9, ≥40 pack years), fiber intake (quintiles), regular use of aspirin, non-aspirin NSAIDs, and acetaminophen.

Additionally adjusted for processed red meat intake or unprocessed red meat intake (quintiles).

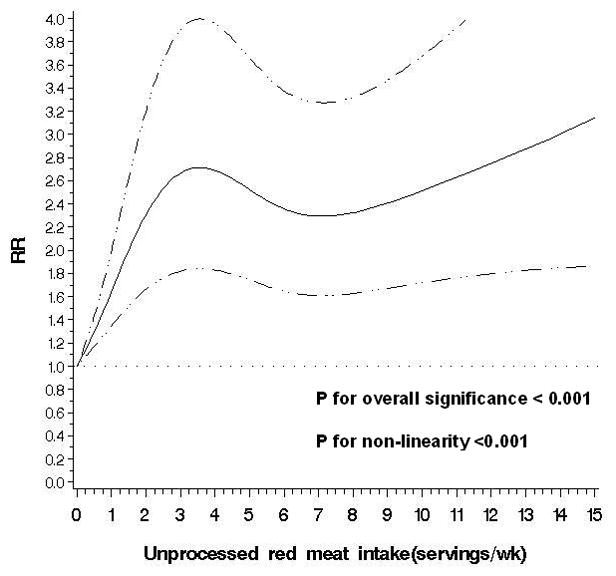

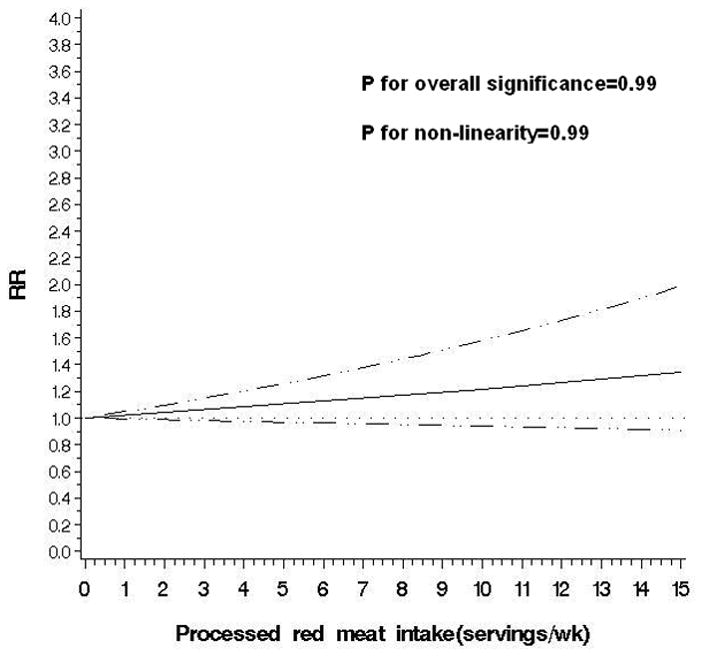

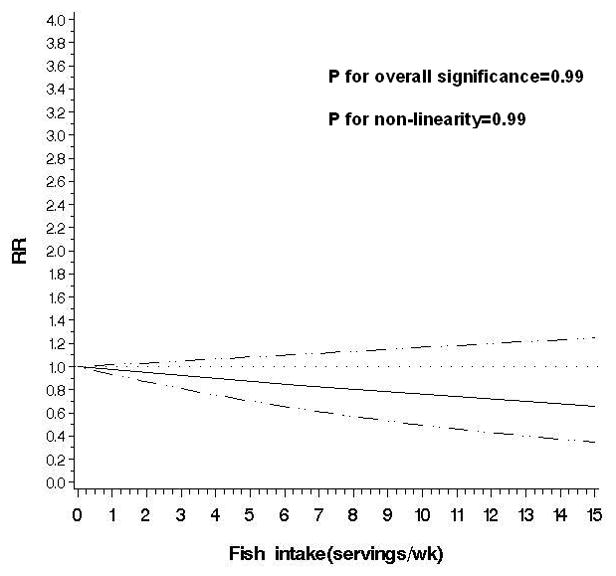

Figure 2.

Non-parametric restricted cubic splines of meat intake (servings/wk) and risk of diverticulitis.

a. Total red meat

b. Unprocessed red meat

c. Processed red meat

d. Poultry

e. Fish

The observed link between total red meat intake and risk of diverticulitis appeared primarily driven by consumption of unprocessed red meat. Men in the highest quintile of unprocessed meat consumption had an RR of 1.51 (95% CI: 1.12, 2.03; P for trend=0.03) compared to men in the lowest quintile, even after adjusting for processed red meat intake. In contrast, processed red meat was associated with increased risk of diverticulitis only in the age-adjusted model, but not after further controlling for other covariates, without or with adjustment for unprocessed red meat (RR for the highest vs lowest quintile 1.03; 95% CI: 0.78,1.35; P for trend=0.26). Additional adjustment for red meat components including total fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, and heme iron minimally changed the associations observed above (data not shown). The findings were similar among overweight and obese men, and men who were younger than 60 or aged 60 and above.

An exploratory analysis of major red meat components indicated a modest association between total fat intake and diverticulitis (RR for the highest vs lowest quintile 1.33; 95% CI: 1.00, 1.77) after adjusting for unprocessed and processed red meat intake (Supplemental Table 1). Poultry was not associated with risk of incident diverticulitis (RR for the highest vs lowest quintile 1.09; 95% CI: 0.86, 1.39; P for trend=0.55) (Table 2). Higher fish intake was associated with reduced risk of diverticulitis in age-adjusted model, but not after further adjustment for other potential confounders (RR for the highest vs lowest quintile 0.87; 95% CI: 0.68, 1.10; P for trend=0.20). The multivariable RR of diverticulitis associated with substitution of poultry or fish for one serving of unprocessed red meat per day was (0.80; 95% CI: 0.63, 0.99). In contrast, substituting one serving of red processed meat per day with poultry or fish was not significantly associated with risk of diverticulitis (RR 0.86; 95% CI: 0.67, 1.09).

DISCUSSION

In this large prospective cohort of men, total red meat intake, especially consumption of unprocessed red meat, was non-linearly associated with an increased risk of diverticulitis. Moreover, we identified unprocessed red meat, but not processed red meat, as the major driver for the link between red meat and diverticulitis. The association was independent of fiber intake. As a component of red meat, total fat intake was associated with an increased risk of diverticulitis even after adjusting for unprocessed and processed red meat intake. In contrast, higher consumption of poultry/fish was not linked with risk of incident diverticulitis. However, substitution of one serving of unprocessed red meat per day with poultry or fish was associated with a 20% lower risk of diverticulitis

Our findings were generally in line with our prior early analysis that red meat, but not poultry or fish, are associated with an increased risk of diverticular disease. However, in this study we were able to examine diverticulitis separately from diverticular bleeding and symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease, rather than utilizing a composite endpoint. In addition, in comparison to the prior study of red meat in the HPFS cohort,12 our cohort included 22 additional years of follow-up and more than twice as many cases.

Pathways through which red meat consumption may influence risk of diverticulitis are yet to be established. Chronic low-grade systemic inflammation may be an essential step.5 Higher red meat intake is associated with higher levels of inflammatory biomarkers such as C-reactive protein and ferritin,23 as well as an increased risk of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancer, in which chronic inflammation has been implicated in the pathogenesis.24–26 The gut microbiome may also mediate the link between red meat and diverticulitis. Emerging evidence suggest that short- and long-term diet, particularly red meat intake, alters microbial community structure, overwhelms inter-individual differences in microbial gene expression, and changes the metabolism of bacteria in the colon.27 Although a direct link between the gut microbiome and diverticulitis is yet to be established,28 it is recently hypothesized that changes in intestinal microbiota composition may play a similar role in the development of diverticular disease and its complications.29 Specifically, changes in the microbiota composition lead to deficiencies of host immune defenses and dysfunction of the mucosal barrier resulting in increased mucosal adherence and translocation of bacteria. A pathogenic immune response is then activated and the release of proinflammtory cytokines further induces inflammation, leading to symptoms.30

We also observed that unprocessed red meat, but not processed red meat, was the primary driver for the association between total red meat and risk of diverticulitis. Compared to processed meat, unprocessed meat (e.g. steak) is usually consumed in larger portions, which could lead to a larger undigested piece in the large bowel, and induce different changes in colonic microbiota. In addition, higher cooking temperatures used in the preparation of unprocessed meat may influence bacterial composition or proinflammory mediators in the colon. These hypotheses need to be confirmed by other studies.

The strengths of our study include a large, well-characterized population with detailed, prospective and updated assessment of meat consumption over 26 years of follow-up. We were also able to differentiate diverticulitis from diverticular bleeding and uncomplicated diverticulosis. As these manifestations appear to arise via different biologic mechanisms, they are likely to have distinct risk factors. In addition, the large number of cases of diverticulitis accrued during long-term follow-up in this study allowed us to examine subtype-specific meat consumption and its dose-response relationship with risk of incident diverticulitis.

There are also limitations of this study. First, misclassification of self-reported outcome was likely. However, health care professionals are more likely to accurately self-report medical information, and reports of diverticulitis have been validated in this cohort.10,11,17 Secondly, measurement errors associated with recall of meat consumption as well as potential confounders were possible; however, they would be non-differential to diagnosis of diverticulitis. Thirdly, even though we able to adjust for a variety of potential confounders, the possibility of residual confounding can never be ruled out. In addition, due to limited number of people consuming a vegetarian diet, we were unable to estimate the substitution effect of a vegetarian dish. Finally, the generalizability of our data to other populations, particularly women and other racial or ethnic groups, may be limited.

CONCLUSION

In summary, we found that intake of red meat, particularly unprocessed red meat, was associated with an increased risk of diverticulitis. Substitution of unprocessed red meat with poultry or fish may reduce the risk of diverticulitis. Our findings may provide practical dietary guidance for patients at risk of diverticulitis, a common disease of huge economic and clinical burden. The mechanisms underlying the observed associations require further investigation.

Supplementary Material

Summary Box.

1. What is already known about this subject: 3–4 bullet points

Diverticulitis is a common disease that results in enormous clinical and economic burden.

Little is known about its epidemiology and etiopathogenesis.

Besides dietary fiber, the role of other dietary factors in the prevention of diverticulitis is under explored.

2. What are the new findings: 3–4 bullet points

Red meat intake, particularly unprocessed red meat intake, was associated with an increased risk of diverticulitis.

Substitution of unprocessed red meat per day with poultry or fish may reduce the risk of diverticulitis.

3. How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

The findings may provide practical dietary guidance for patients at risk of diverticulitis.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by grants R01 DK101495, R01 DK084157, K24 DK 098311, and UM1 CA167552 from the National Institutes of Health.

We would like to thank the participants and staff of the Health Professionals Follow-up Study for their valuable contributions.

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- FFQ

food frequency questionnaires

- HPFS

Health Professionals Follow-up Study

- MET

metabolic equivalent task

- NSAIDs

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- RR

relative risk

Footnotes

Role of sponsor: The study sponsors have no role in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data.

Competing interests: A.T.C. previously served as a consultant for Bayer Healthcare, Pozen and Pfizer for work unrelated to the topic of this manuscript. This study was not funded by Bayer Healthcare, Pozen or Pfizer.

Author Contributions: Drs Cao and Chan had full access to all of the data in the study, and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Y.C., L.L.S., E.L.G., A.T.C.

Acquisition of data: L.L.S., B.R.K., I.T., A.T.C.

Analysis and interpretation of data: all coauthors

Drafting of the manuscript: Y.C.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all coauthors

Statistical analysis: Y.C.

Obtained funding: L.L.S., E.L.G., A.T.C.

Administrative, technical, or material support: L.L.S., A.T.C.

Study supervision: L.L.S., A.T.C.

References

- 1.Peery AF, Crockett SD, Barritt AS, Dellon ES, Eluri S, Gangarosa LM, et al. Burden of Gastrointestinal, Liver, and Pancreatic Diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1731. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen GC, Sam J, Anand N. Epidemiological trends and geographic variation in hospital admissions for diverticulitis in the United States. World journal of gastroenterology : WJG. 2011;17:1600–5. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i12.1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bharucha AE, Parthasarathy G, Ditah I, Fletcher JG, Ewelukwa O, Pendlimari R, et al. Temporal Trends in the Incidence and Natural History of Diverticulitis: A Population-Based Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1589–96. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shahedi K, Fuller G, Bolus R, Cohen E, Vu M, Shah R, et al. Long-term Risk of Acute Diverticulitis Among Patients With Incidental Diverticulosis Found During Colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol H. 2013;11:1609–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strate LL, Modi R, Cohen E, Spiegel BMR. Diverticular Disease as a Chronic Illness: Evolving Epidemiologic and Clinical Insights. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2012;107:1486–93. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hjern F, Wolk A, Hakansson N. Smoking and the risk of diverticular disease in women. The British journal of surgery. 2011;98:997–1002. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Humes DJ, Fleming KM, Spiller RC, West J. Concurrent drug use and the risk of perforated colonic diverticular disease: a population-based case-control study. Gut. 2011;60:219–24. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.217281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strate LL, Liu YL, Huang ES, Giovannucci EL, Chan AT. Use of Aspirin or Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs Increases Risk for Diverticulitis and Diverticular Bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1427–33. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hjern F, Wolk A, Hakansson N. Obesity, Physical Inactivity, and Colonic Diverticular Disease Requiring Hospitalization in Women: A Prospective Cohort Study. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2012;107:296–302. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strate LL, Liu YL, Aldoori WH, Giovannucci EL. Physical Activity Decreases Diverticular Complications. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2009;104:1221–30. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strate LL, Liu YL, Aldoori WH, Syngal S, Giovannucci EL. Obesity Increases the Risks of Diverticulitis and Diverticular Bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:115–22. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aldoori WH, Giovannucci EL, Rimm EB, Wing AL, Trichopoulos DV, Willett WC. A Prospective-Study of Diet and the Risk of Symptomatic Diverticular-Disease in Men. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1994;60:757–64. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/60.5.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crowe FL, Appleby PN, Allen NE, Key TJ. Diet and risk of diverticular disease in Oxford cohort of European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC): prospective study of British vegetarians and non-vegetarians. Brit Med J. 2011:343. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Giovannucci E, Willett WC. Effectiveness of various mailing strategies among nonrespondents in a prospective cohort study. American journal of epidemiology. 1990;131:1068–71. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu FB, Rimm E, Smith-Warner SA, Feskanich D, Stampfer MJ, Ascherio A, et al. Reproducibility and validity of dietary patterns assessed with a food-frequency questionnaire. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:243–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feskanich D, Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Litin LB, et al. Reproducibility and validity of food intake measurements from a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1993;93:790–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(93)91754-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strate LL, Liu YL, Syngal S, Aldoori WH, Giovannucci EL. Nut, corn, and popcorn consumption and the incidence of diverticular disease. JAMA. 2008;300:907–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.8.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith PL. Splines as a Useful and Convenient Statistical Tool. Am Stat. 1979;33:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrell FE, Jr, Lee KL, Pollock BG. Regression models in clinical studies: determining relationships between predictors and response. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1988;80:1198–202. doi: 10.1093/jnci/80.15.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durrleman S, Simon R. Flexible Regression-Models with Cubic-Splines. Stat Med. 1989;8:551–61. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halton TL, Willett WC, Liu S, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Hu FB. Potato and french fry consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:284–90. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernstein AM, Sun Q, Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Willett WC. Major dietary protein sources and risk of coronary heart disease in women. Circulation. 2010;122:876–83. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.915165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ley SH, Sun Q, Willett WC, Eliassen AH, Wu K, Pan A, et al. Associations between red meat intake and biomarkers of inflammation and glucose metabolism in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:352–60. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.075663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Micha R, Michas G, Mozaffarian D. Unprocessed red and processed meats and risk of coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes--an updated review of the evidence. Current atherosclerosis reports. 2012;14:515–24. doi: 10.1007/s11883-012-0282-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan A, Sun Q, Bernstein AM, Schulze MB, Manson JE, Willett WC, et al. Red meat consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: 3 cohorts of US adults and an updated meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:1088–96. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.018978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan DS, Lau R, Aune D, Vieira R, Greenwood DC, Kampman E, et al. Red and processed meat and colorectal cancer incidence: meta-analysis of prospective studies. PloS one. 2011;6:e20456. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505:559. doi: 10.1038/nature12820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gueimonde M, Ouwehand A, Huhtinen H, Salminen E, Salminen S. Qualitative and quantitative analyses of the bifidobacterial microbiota in the colonic mucosa of patients with colorectal cancer, diverticulitis and inflammatory bowel disease. World journal of gastroenterology : WJG. 2007;13:3985–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i29.3985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daniels L, Philipszoon LE, Boermeester MA. A hypothesis: important role for gut microbiota in the etiopathogenesis of diverticular disease. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2014;57:539–43. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guarner F, Malagelada JR. Gut flora in health and disease. Lancet. 2003;361:512–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12489-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.