Abstract

Objective

Despite advances in supported treatments for early-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), progress has been constrained by regionally limited expertise in pediatric OCD. Videoteleconferencing (VTC) methods have proved useful for extending the reach of services for older individuals, but no randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have evaluated VTC for treating early-onset OCD.

Method

RCT comparing VTC-delivered family-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (FB-CBT) versus clinic-based FB-CBT in the treatment of children ages 4–8 with OCD (N=22). Pretreatment, posttreatment, and 6-month follow-up assessments included mother-/therapist-reports and independent evaluations masked to treatment condition. Primary analyses focused on treatment retention, engagement and satisfaction. Hierarchical linear modeling preliminarily evaluated the effects of time, treatment condition, and their interactions. “Excellent response” was defined as a 1 or 2 on the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement Scale.

Results

Treatment retention, engagement, alliance and satisfaction were high across conditions. Symptom trajectories and family accommodation across both conditions showed outcomes improving from baseline to posttreatment, and continuing through follow-up. At posttreatment, 72.7% of Internet cases and 60% of Clinic cases showed “excellent response,” and at follow-up 80% of Internet cases and 66.7% of Clinic cases showed “excellent response.” Significant condition differences were not found across outcomes.

Conclusions

VTC methods may offer solutions to overcoming traditional barriers to care for early-onset OCD by extending the reach of real-time expert services regardless of children’s geographic proximity to quality care.

Keywords: behavioral telehealth, videoteleconferencing, OCD, early intervention, early childhood

Although research on treating pediatric OCD has historically focused on OCD in middle childhood and adolescence (e.g., Barrett et al., 2004; Pediatric OCD Treatment Study Team, 2004; Piacentini et al., 2002), recent years have witnessed substantial advances in the development of family-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (FB-CBT) methods for redressing the problems of early-onset OCD (i.e., onset < age 9; Freeman et al., 2008, 2014). For example, in a recent randomized controlled trial (RCT), Freeman and colleagues (2014) found their FB-CBT program to be superior to family-based relaxation training (RT) in the treatment of 5–8 year olds with OCD, with 72% of FB-CBT-treated youth showing excellent response versus only 41% of RT-treated youth.

Despite advances, obstacles to quality care remain, including limited numbers of professionals trained in early-onset OCD, poor quality of available services, long waitlists, stigma, and transportation issues (see Comer & Barlow, 2014; Comer et al., 2014). Technological innovations may offer useful solutions to overcoming traditional barriers to effective care—particularly for low base rate conditions with regionally limited specialty care options, such as early-onset OCD (Comer, 2015; Comer & Barlow, 2014; Comer et al., 2014; Kazdin & Blase, 2011). Notably, videoteleconferencing (VTC) methods have shown success in overcoming geographical obstacles to quality care in the treatment of a range of child internalizing and externalizing problems (e.g., Comer et al., 2015; Duncan, Velasquez, & Nelson, 2014; Jones et al., 2014; Nelson et al., 2016) by extending the reach of expert services, addressing regional workforce shortages, and overcoming issues of transportation, stigma, and quality of care even in regions that do offer clinic-based services (see Comer et al., 2014; Crum & Comer, 2016; Duncan, Velasquez, & Nelson, 2014). Patient populations can participate in real-time services conducted by experts, regardless of their geographic proximity to an expert mental health facility. Moreover, leveraging technology to deliver interventions in natural settings (e.g., homes) may extend the ecological validity of treatments, as services can be offered in the very settings where many problems occur.

Despite promise, remote VTC strategies for pediatric OCD have received only limited empirical attention. In the only controlled evaluation, Storch and colleagues (2011) found 81% of VTC-treated youth in middle childhood and adolescence with OCD met posttreatment responder criteria, compared to only 13% of waitlist youth. Such findings speak to the incremental benefits of VTC care relative to expectations of future treatment, but cannot speak to comparisons with empirically supported standards of care. To date, there have been no controlled evaluations to date of VTC methods for treating early-onset OCD. In one case series, Comer and colleagues (2014) remotely treated five young children with OCD between the ages of 4 and 8 with VTC-delivered FB-CBT. This real-time, Internet-based interactive VTC format offered a comparable quantity of therapist contact to standard FB-CBT; all five families completed a full treatment course, all showed symptom improvements, all showed at least partial diagnostic response, and all treated children’s mothers characterized the quality of services received as “excellent.”

The present pilot RCT is the first randomized evaluation of Internet-delivered treatment versus supported clinic-based treatment for early-onset OCD. Given the early success of VTC methods for treating older youth with OC-spectrum disorders (e.g.,Himle et al., 2012; Storch et al., 2011) as well as the results of Comer and colleagues (2014), we hypothesized that VTC-delivered FB-CBT in this pilot trial would yield strong engagement (as measured via high treatment completion), therapeutic alliance, and satisfaction. In secondary analyses, we hypothesized that VTC-delivered FB-CBT would yield significant symptom and diagnostic improvements across time, and that condition differences between VTC-delivered and clinic-based FB-CBT would not be supported, as evidenced by similar outcome trajectories and rates of response. Given strong links between pediatric OCD and patterns of family accommodation (e.g., Caporino et al., 2012), exploratory analyses also examined the extent to which the two treatment conditions yielded improvements in parental accommodation.

Method

Participants

Table 1 presents study eligibility criteria and baseline characteristics of study participations (N=22).

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria, demographic, and clinical characteristics of sample (N=22).

| Eligibility Criteria

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of sample (N=22)

| ||

| M (SD) | % (N) | |

|

|

||

| Child age, in years | 6.65 (1.3) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 59.1 (13) | |

| Female | 40.9 (9) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian/Non-Hispanic/Latino | 91.0 (20) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 4.5 (1) | |

| Biracial | 4.5 (1) | |

| Maternal age, in years | 38.1 (5.1) | |

| Maternal education | ||

| Completed college | 90.9 (20) | |

| Did not complete college | 9.0 (2) | |

| Paternal age, in years | 39.6 (4.0) | |

| Paternal education | ||

| Completed college | 68.2 (15) | |

| Did not complete college | 31.8 (7) | |

| Biological parents’ marital status | ||

| Married | 81.8 (18) | |

| Not married | 18.2 (4) | |

| Annual household incomea | ||

| < $50,000 | 18.2 (4) | |

| $50,000 – $100,000 | 9.1 (2) | |

| > $100,000 | 63.6 (14) | |

| # child diagnoses | 1.7 (0.8) | |

| Child comorbid diagnoses | ||

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 22.7 (5) | |

| Separation anxiety disorder | 18.2 (4) | |

| Social anxiety disorder | 18.2 (4) | |

| ADHD | 13.6 (3) | |

| Specific phobia | 9.1 (2) | |

2 families did not report annual household income

Measures

Outcome measures included have all demonstrated favorable reliability and validity in previous work. Specific details of psychometric support for each measure are available from the corresponding author by request.

Treatment satisfaction and therapeutic alliance

The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8; Larsen, Attkisson, Hargreaves & Nguyen, 1979) is a generic 8-item assessment of consumer satisfaction with services received (α=.86 in present sample). Posttreatment mother-reports were included in the present study. The Working Alliance Inventory (WAI; Horvath, 1994) is a 36-item assessment of perceptions of the quality of therapeutic rapport and collaboration in treatment. Respondents rate each item on a scale from 1 (Never) to 7 (Always) to characterize their perceptions of the affective bond between the client and therapist and the extent of their agreement about the goals and tasks of treatment. We included posttreatment mother- and therapist-WAI total reports (αMother =.90 and αTherapist=.70 in present sample).

Diagnostic, symptom, severity, and impairment outcomes

The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children and Parents for DSM–IV (ADIS-IV-C/P; Silverman & Albano, 1996) is a semi-structured diagnostic interview that assesses child psychopathology in accordance with DSM–IV. We administered the ADIS-P (parent version) for all children. The ADIS-C (child version) was also administered for youth ages 7–8, and parent and child diagnostic profiles were integrated using the “or” rule (see Comer & Kendall, 2004). DSM-IV diagnoses are assigned and clinical severity ratings (CSRs) range from 0–8 (CSR ≥4 denotes full diagnostic criteria met). The Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS; Scahill et al., 1997) is a 10-item, semi-structured, clinician-rated interview. CY-BOCS Total score ranges include: “subclinical” (0–7), “mild” (8–15), “moderate” (16–23), “severe” (24–31), and “extreme” (32–40) (α=.78 in present sample). The Clinical Global Impression-Severity and Improvement Scales (CGI-S/I) is the most widely used clinician-rated measure of treatment-related changes in functioning (Guy & Bonato, 1970). CGI-S rates illness severity on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (“normal”) to 7 (“among the most severely ill patients”); CGI-I rates clinical improvement on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (“very much improved”) to 7 (“very much worse”). CGI-I scores of 1 or 2 reflect “excellent response”. The Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS; Shaffer et al., 1983) is a widely used clinician-rated measure of overall child disturbance in functioning (range: 0–100; lower scores = greater impairment).

Family accommodation

The Family Accommodation Scale-Parent Report (FAS-PR; Flessner et al., 2009) assesses caregiver reports of family member participation in children’s OCD rituals, including the facilitation of child avoidance, modification of family/parent routines in response to child OCD symptoms, and direct involvement in child compulsions (α=.81 in present sample).

Treatment

FB-CBT (Freeman & Garcia, 2009) is a 14-week clinic-based program drawing on supported CBT approaches used with older youth. FB-CBT contains exposure and response prevention (E/RP) modifications tailored specifically for developmental compatibility with children ages 4–8, with an awareness of young children’s primary dependence on the family system and with appreciation for the restricted cognitive and capacities characteristic of early childhood. Parents are trained as coaches for their children, ensuring out-of-session adherence and motivation; parental accommodation of child symptoms is an explicit treatment focus. Parents are taught to use differential attention, modeling, and scaffolding techniques to manage child symptoms. Children learn to externalize their symptoms by “bossing back” OCD. Therapists work with parents and children to create a fear hierarchy that guides graduated E/RP tasks.

Internet-delivered FB-CBT

Internet-delivered FB-CBT follows the same 14-week Freeman and Garcia (2009) program, but uses a VTC platform to allow therapists to remotely deliver real-time treatment to families directly in their homes. Internet-delivered FB-CBT offers a comparable quantity of therapist time as in clinic-based FB-CBT. Ethical and administrative considerations for use of VTC to deliver treatment are considered elsewhere (Crum & Comer 2016; Kramer, Kinn, & Mishkind, 2015), as are details on specific hardware and equipment used in the present work (Comer et al., 2014). Our work relied on easy-to-use web conferencing appliances that are compliant with existing practice standards for VTC-delivered treatment. In lieu of collaborative in-room activities that are central to clinic-based FB-CBT, we used a series of interactive computer games to enhance children’s understanding of treatment concepts (see Comer et al., 2014). Further details of how treatment was adapted for VTC can be found elsewhere (Comer et al., 2014)

Procedure

The recruitment, treatment, and follow-up assessment phases were 3/5/12–7/30/15, 4/5/12–8/4/15, and 2/1/13–2/24/16, respectively. Procedures were approved by the [removed for review] IRB. IEs and therapists (N=7) were masters-level trainees in clinical psychology. Participating families were recruited from families seeking services at the [removed for review]. An independent evaluator (IE) collected informed consent and then conducted a baseline ADIS and CY-BOCS. CGAS and CGI scores were subsequently generated by the IE. Families meeting eligibility were then evenly randomized using a two-digit random number generator to receive either clinic-based or VTC-based FB-CBT. Treatment was provided at no cost. Families participated in 12 sessions across 14 weeks. VTC families were provided with a temporary equipment kit (~$200; see Comer et al., 2014), although most families independently possessed sufficient equipment. Therapist and IE training procedures, as well as security and confidentiality procedures for VTC treatment, are presented elsewhere (Comer et al., 2014). Interrater agreement on categorical codes (i.e., CGI-I/S, OCD diagnosis) was high (i.e., >80% interrater agreement after training and >80% interrater agreement on study cases). The same team of therapists provided treatment in both conditions. Treatment integrity checklists were completed on 10% of sessions; treatment integrity was high (94%) and did not significantly differ across the conditions. At posttreatment and again at 6-month follow-up, families met with IEs masked to treatment condition who conducted ADIS and CY-BOCS interviews and generated CGAS and CGI scores. Parents completed baseline, posttreatment, and 6-month follow-up forms via an online survey application. Families received $45 for completing each assessment point.

Results

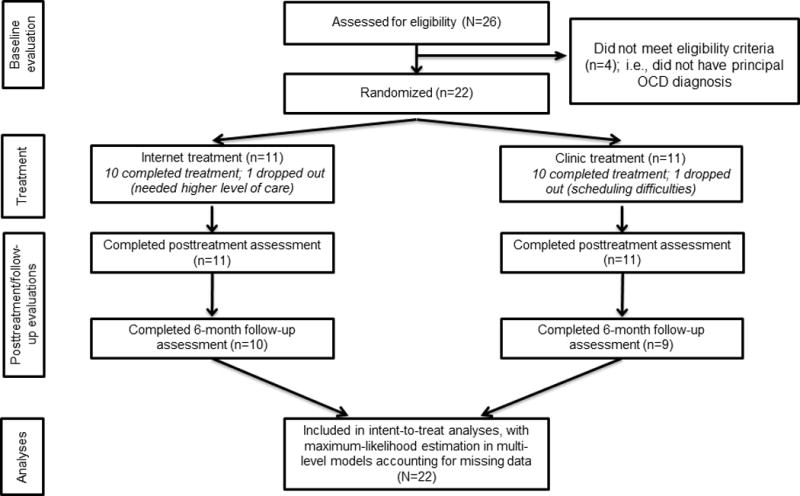

Treatment retention was high, with 90.9% of families completing the full course of treatment of 12 sessions. One Internet FB-CBT family dropped out after session 1 and one Clinic FB-CBT family dropped out after session 10. 100% of families participated in the posttreatment assessment and 86.4% of families participated in the 6-month follow-up assessment (see Figure 1). There were no significant differences between families who did and did not participate in the follow-up assessment. Missing value analysis showed missingness on outcome variables was not related to condition, previous waves of the same variable, or demographic variables, a missingness pattern consistent with missing at random (MAR). HLM mixed-effects models in the present analysis utilized data from the intent-to-treat sample, accounting for missing data using maximum likelihood (ML) estimation, which produces unbiased estimates when data are MAR. Families did not differ across conditions on any baseline demographic or clinical variables. Mothers participated in treatment for 95.5% (N=21) of cases. Fathers participated in treatment for 68.2% of cases.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants across study phases

Table 2 presents data across conditions regarding treatment engagement and satisfaction. Significant differences were not found across conditions with regard to treatment retention or session tardiness. All but one family in each condition completed a full course of treatment, and families in both conditions started less than half of their sessions on time (i.e., within 10 minutes of schedule). Mother- and therapist-report alliance was very high across conditions. Mothers reported very high treatment satisfaction across conditions.

Table 2.

Engagement and treatment satisfaction across treatment conditions

| Internet-delivered FB-CBT | Clinic-based FB-CBT | Significance Test | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| M | SD | N | % | M | SD | N | % | ||

|

|

|||||||||

| # cases who completed full treatment course | 10 | 90.9 | 10 | 90.9 | |||||

| Mean # sessions/case that started on timea | 5.27 | 4.5 | 5.45 | 3.75 | t(20)= −.10, p=.92 | ||||

| Working allianceb | |||||||||

| Mother-report | 223.45 | 34.8 | 238.60 | 18.2 | t(19)= −1.23, p=.23 | ||||

| Therapist-report | 226.10 | 32.9 | 233.00 | 17.4 | t(18)= −.59, p=.57 | ||||

| Treatment satisfaction (mother-report)b | 28.55 | 4.5 | 30.50 | 2.0 | t(19)= −1.27, p=.22 | ||||

Note: FB-CBT=Family-Based Cognitive-behavioral Therapy (Freeman & Garcia, 2009)

Starting “on time” was defined as session starting within 10 minutes of scheduled start time

Assessed at posttreatment

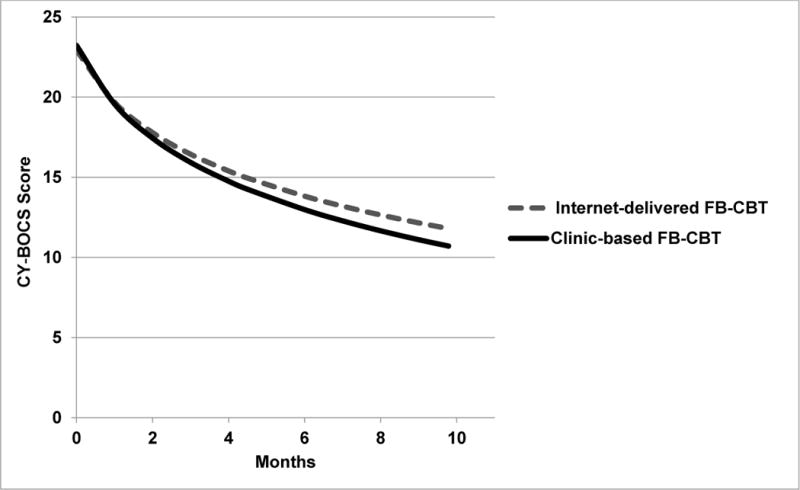

HLM using ML estimation was used to model the non-independence due to nesting of repeated observations (level 1) within participants (level 2). For each HLM, treatment condition and the natural log (ln) of time were fixed effect predictors; the group × ln(time) interaction was also included. A random intercept allows individuals to vary in their mean outcome value. A random slope with respect to time was omitted due to the small sample size. Table 3 presents model estimated means for all clinical outcomes, by treatment condition, across the assessments points. Table 4 presents the results of analyses examining the effects of time, condition, and their interactions on clinical outcomes. For every clinical outcome there was a significant effect of time across subjects (Table 4). Across outcomes, there were no significant interaction effects of time×condition. Figure 2 presents the symptom trajectory, by condition, for CY-BOCS scores; the general shape of change depicted is comparable for all outcomes. Table 5 presents data on the clinical significance of outcomes across time. Within-subjects effect sizes from pre-to-post and from pre-to-follow-up were mostly large in magnitude. Between 60–80% of participants showed clinically significant responder statuses as assessed via the CGI-I (score of 1 or 2), the CY-BOCS (“subclinical”/“mild” range; i.e., score ≤ 15), and the ADIS-C/P (no OCD diagnoses) at posttreatment and at follow-up. Differences between conditions on clinical significance responder statuses were non-significant (see Table 5).

Table 3.

Clinical outcomes across assessment points, by condition.

| Internet-delivered FB-CBT | Clinic-based FB-CBT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Outcome | Pre M(SD) |

Post M(SD) |

6 month follow-up M(SD) |

Pre M(SD) |

Post M(SD) |

6 month follow-up M(SD) |

| Child OCD symptoms | ||||||

| CY-BOCS total | 22.9(4.1) | 14.9(7.3) | 11.8(9.5) | 23.2(3.2) | 14.2(7.8) | 10.7(8.3) |

| OCD CSR | 5.1(.8) | 3.4(1.2) | 2.4(2.6) | 4.9(.9) | 3.1(1.3) | 2.4(2.7) |

| Child global severity and functioning | ||||||

| CGI-S | 4.9(.7) | 3.2(1.5) | 2.6(2.5) | 4.6(.9) | 3.3(1.6) | 2.8(1.6) |

| CGAS | 48.0(8.0) | 61.4(12.0) | 66.6(15.9) | 54.6(9.5) | 62.2(15.0) | 65.1(14.3) |

| Family accommodation | 29.5(7.8) | 19.5(9.7) | 15.6(14.2) | 21.1(6.7) | 14.8(6.9) | 12.4(4.3) |

Note: Means reflect model estimated means (not raw means); FB-CBT=Family-Based Cognitive-behavioral Therapy (Freeman & Garcia, 2009); CY-BOCS=Child Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale; CSR=Clinical Severity Rating; CGI-S=Clinical Global Impression-Severity Scale

Table 4.

Results of mixed-effects models examining the effects of condition, time, and their interactions

| Condition | Time | Condition × Time Interaction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| b | p | b | p | b | p | |

|

|

||||||

| Child OCD symptoms | ||||||

| CY-BOCS Total | .3 | .91 | −4.7 | <.0001 | −.6 | .73 |

| OCD CSR | −.2 | .65 | −1.0 | <.0001 | .1 | .93 |

| Child global severity and functioning | ||||||

| CGI-S | −.4 | .53 | −1.0 | <.0001 | .2 | .45 |

| CGAS | 6.6 | .21 | 7.8 | <.0001 | −3.4 | .15 |

| Family accommodation | −6.3 | .19 | −5.8 | <.0001 | 2.1 | .22 |

Note: CY-BOCS=Child Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale; CSR=Clinical Severity Rating; CGI-S=Clinical Global Impression-Severity Scale

Figure 2.

Trajectories of change across months, by treatment condition, for scores on the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS)

Note: The average timing of treatment completion was 4.52 months post-baseline assessment; the average timing of the follow-up evaluation was 9.79 months post-baseline assessment. The general quadratic shape of change depicted here for CY-BOCS scores is comparable for all other clinical outcomes assessed.

Table 5.

Clinical significance of outcomes, by treatment condition

|

Within-subjects effect sizes (d) across clinical outcomes, by treatment condition

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internet-delivered FB-CBT | Clinic-based FB-CBT | |||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Pre vs Post | Pre vs Follow-up | Pre vs Post | Pre vs Follow-up | |||||

|

|

||||||||

| Child OCD symptoms | ||||||||

| CY-BOCS Total | 1.53 | 1.27 | 1.64 | 1.45 | ||||

| OCD CSR | 1.67 | 1.06 | 1.40 | .80 | ||||

| Child global severity and functioning | ||||||||

| CGI-S | 1.59 | 1.16 | 1.09 | .83 | ||||

| CGAS | −1.29 | −1.43 | −.73 | −.77 | ||||

| Family accommodation | 1.38 | 1.03 | 1.41 | 1.38 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

|

Between-subjects effect sizes (d) across clinical outcomes

| ||||||||

| At Post | At Follow-up | |||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Child OCD symptoms | ||||||||

| CY-BOCS Total | .09 | .12 | ||||||

| OCD CSR | .24 | .00 | ||||||

| Child global severity and functioning | ||||||||

| CGI-S | −.06 | −.01 | ||||||

| CGAS | −.06 | .10 | ||||||

| Family accommodation | .56 | .31 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

|

Responder statuses, by treatment condition

| ||||||||

| Posttreatment | 6-month follow-up | |||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Internet % | Clinic % | Significance test | Internet % | Clinic % | Significance test | |||

|

|

||||||||

| Excellent responder1 | 72.7 | 60.0 | χ2(1, N=22)=.38, p=.66 | 80.0 | 66.7 | χ2(1, N=17)=.43, p=.63 | ||

| “Sub-clinical”/”mild” OCD severity2 | 72.7 | 60.0 | χ2(1, N=22)=.38, p=.54 | 55.6 | 75.0 | χ2(1, N=17)=.70, p=.40 | ||

| No OCD diagnosis3 | 63.3 | 60.0 | χ2(1, N=22)=.03, p=.86 | 70.0 | 77.8 | χ2(1, N=17)=.15, p=.70 | ||

Note: FB-CBT=Family-Based Cognitive-behavioral Therapy (Freeman & Garcia, 2009); CY-BOCS=Child Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale; CSR=Clinical Severity Rating; CGI-S=Clinical Global Impression-Severity Scale; CGI-I=Clinical Global Impression-Improvement Scale

Score of 1 (“very much improved”) or 2 (“much improved”) on CGI-I

≤ 15 on CY-BOCS

As determined via the ADIS-IV-C/P

Discussion

The present findings provide the first empirical support from a controlled trial evaluating the potential utility of leveraging VTC technology to remotely deliver real-time treatment for early-onset OCD. Internet-delivered FB-CBT showed strong engagement and satisfaction, with roughly 90% of Internet-treated youth completing a full course of treatment, mothers and therapists both reporting high therapeutic alliance, and mothers reporting very high satisfaction with services received. At posttreatment, roughly three-fourths of Internet cases showed an “excellent response,” and at follow-up four-fifths showed an “excellent response.” Differences between treatment formats across time were not supported, and response rates among Internet-treated youth were also roughly comparable to those found in previous work evaluating clinic-based FB-CBT (Freeman et al., 2008, 2014). These findings build on the small but growing body of work supporting the promising role of VTC formats for broadening the delivery of CBT for OCD and related disorders across the lifespan (Herbst et al., 2012; Himle et al., 2012; Storch et al., 2011; Wootton, 2016), and add to a broader literature documenting the potential role of new technologies for meaningfully expanding the reach of supported mental health care (Comer, 2015; Comer & Barlow, 2014; Comer et al., 2014; Kazdin & Blase, 2011). Taken together, the present findings speak to the overall feasibility and acceptability of Internet-delivered FB-CBT, and to its preliminary efficacy.

Although dissemination and implementation efforts have already had an appreciable impact on mental health services, given the great diversity of mental health problems, broad training efforts of regional generalist providers alone may not be sufficient to adequately address the tremendous prevalence and burden of child disorders. As Comer and Barlow (2014) note, the considerable resources required for quality dissemination and implementation may preclude large-scale competency training in the treatment of low base-rate disorders, such as pediatric OCD, in order to prioritize the most common conditions affecting the general population. Moreover, treatment innovations that are too complex do not get routinely incorporated (or incorporated with fidelity) into frontline practice (Rogers, 2003). Given the broad diversity of training and educational backgrounds across the mental health workforce, specialized/complex treatment methods for low base-rate disorders (such as E/RP for pediatric OCD), may not readily lend themselves to broad dissemination and implementation efforts. Indeed, “putting all of our eggs in the dissemination basket” and in the broad training of a generalist mental health workforce (see Comer & Barlow, 2014) may not adequately ensure appropriate and accessible care for young children with low base-rate problems such as OCD that require complex treatments. With continued support, VTC-delivered E/RP may prove to be a useful solution for broadly delivering expert services for severe conditions that may not readily lend themselves to traditional dissemination methods.

Several limitations merit comment. First, the sample size in this pilot RCT may have been underpowered to detect some differences, although all within-group analyses did yield significant results. Future work with larger samples is needed to replicate these promising results and to evaluate mechanisms of treatment response, including potential mediators and moderators. Second, the present sample was predominantly urban, Caucasian, and of relatively high socioeconomic advantage. Future research must improve efforts to recruit affected families from more diverse backgrounds. Third, participants were recruited from a metropolitan-based clinic and as such findings may not generalize to more remote communities with limited access to computers, technological literacy, and/or clinic-based services. Indeed, the present findings may speak to the generic potential of Internet-delivered treatments, particularly with regard to issues of ecological validity associated with treating families in their homes and other natural settings, but cannot speak to whether VTC methods can effectively treat rural youth, economically depressed youth, or other populations underserved by quality clinic-based services. Encouragingly, as of 2015, over 50% of rural households and over 60% of households earning $20,000–$40,000 already have household broadband Internet connections (Pew Research Center, 2015). As we approach household Internet connectivity for all, regardless of geography and income, proof-of-concept trials such as this are essential to evaluating the preliminary merits of Internet-delivered treatments, but future efforts are needed to examine treatment responses in families living in underserved regions.

Moreover, comparing two active treatments in the absence of a “no treatment” condition precludes consideration of the extent to which effects may simply reflect the passage of time. However, previous pediatric OCD trials utilizing waitlist controls (e.g., Barrett et al., 2004) suggest that the simple passage of time does not yield significant improvements. In addition, the present study evaluated remote delivery of a treatment protocol designed to treat early child OCD, and as such we only included youth ages 4 to 8. Future research should examine treatment outcomes across a wider age range of children with OCD, and to consider whether Internet-delivered treatment is comparably effective across different age groups. Finally, it is possible that the in-session interactive computer games (designed for Internet-delivered FB-CBT to enhance children’s understanding of treatment concepts in the way in-office collaborative art projects do in clinic-based treatment) resulted in differential treatment dosages across conditions.

Despite limitations, the present study offers the first randomized evaluation of VTC methods for providing treatment to young children with early-onset OCD, and provides support for the acceptability and preliminary efficacy of Internet-delivered FB-CBT. Amidst a backdrop of workforce shortages in quality mental health care and regional limitations in pediatric OCD expertise, the present findings suggest VTC methods may be a promising vehicle for meaningfully improving the accessibility of needed care. Currently, expert care in pediatric OCD tends to cluster around major metropolitan regions and academic hubs. As Comer and Barlow (2014) note, in the coming years specialty mental health “clinics” may be housed online, rather than geographically bound, and systematically deliver quality treatments for low base-rate disorders that are not easily disseminated. Specialty OCD centers may do well to incorporate VTC strategies to broaden their patient catchment areas and extend evidence-based care to a greater proportion of affected families.

Public Health Significance Statement.

Despite advances in supported treatments for early-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), progress has been constrained by regionally limited expertise in pediatric OCD and local mental health workforce shortages. This proof-of-concept pilot study suggests videoteleconferencing methods could be useful for overcoming traditional barriers to care for early-onset OCD by extending the reach of real-time expert services.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was principally supported by the International OCD Foundation (IOCDF), as well by the NIH (K23 MH090247).

Abbe M. Garcia and Jennifer B. Freeman receive book royalties from Oxford University Press.

References

- Barrett P, Healy-Farrell L, March JS. Cognitive-behavioral family treatment of childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder: A controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:46–62. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200401000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporino N, Morgan J, Beckstead J, Phares V, Murphy T, Storch EA. A structural equation analysis of family accommodation in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40:133–143. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9549-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer JS. Introduction to the special section: Applying new technologies to extend the scope and accessibility of mental health care. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2015;22:253–257. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2015.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Comer JS, Barlow DH. The occasional case against broad dissemination and implementation: Retaining a role for specialty care in the delivery of psychological treatments. American Psychologist. 2014;69:1–18. doi: 10.1037/a0033582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer JS, Furr JM, Cooper-Vince C, Kerns C, Chan PT, Edson AL, Khanna M, Franklin ME, Garcia AM, Freeman JB. Internet-delivered, family-based treatment for early-onset OCD: A preliminary case series. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2014;43:74–87. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.855127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer JS, Furr JM, Cooper-Vince C, Madigan RJ, Chow C, Chan P, Idrobo F, Chase RM, McNeil CB, Eyberg SM. Rationale and considerations for the Internet-based delivery of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2015;22:302–316. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer JS, Kendall PC. A symptom-level examination of parent-child agreement in the diagnosis of anxious youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:878–886. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000125092.35109.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum KI, Comer JS. Using synchronous videoconferencing to deliver family-based mental health care. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2016;26:229–234. doi: 10.1089/cap.2015.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan AB, Velasquez SE, Nelson EL. Using videoconferencing to provide psychological services to rural children and adolescents: A review and case example. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2014;43:115–127. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.836452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flessner CA, Sapyta J, Garcia A, Freeman JB, Franklin ME, Foa E, March J. Examining the psychometric properties of the Family Accommodation Scale-Parent Report (FAS-PR) Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2009;31:38–46. doi: 10.1007/s10862-010-9196-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman JB, Garcia AM. Family Based Treatment for Young Children With OCD: Therapist Guide. USA: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman JB, Garcia AM, Coyne L, et al. Early childhood OCD: preliminary findings from a family-based cognitive-behavioral approach. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(5):593–602. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816765f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman J, Sapyta J, Garcia A, et al. Family-based treatment of early childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder: The Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Treatment Study of Young Children (POTS Jr)—a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:689–698. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W, Bonato RR. Clinical Global Impressions. Chevy Chase, MD: IMH; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Herbst N, Voderholzer U, Stelzer N, et al. The potential of telemental health applications for obsessive–compulsive disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2012;32:454–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himle MB, Freitag M, Walther M, Franklin SA, Ely L, Woods DW. A randomized pilot trial comparing videoconference versus face-to-face delivery of behavior therapy for childhood tic disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2012;50(9):565–570. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath AO. Empirical validation of Bordin’s pan theoretical model of the alliance: The Working Alliance Inventory perspective. In: Horvath AO, Greenberg LS, editors. The working alliance: Theory, research and practice. New York: Wiley; 1994. pp. 109–130. [Google Scholar]

- Jones DJ, Forehand R, Cuellar J, et al. Technology-enhanced program for child disruptive behavior disorders: Development and pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2014;43:88–101. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.822308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Blase SL. Rebooting psychotherapy research and practice to reduce the burden of mental illness. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6:21–37. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer GM, Kinn JT, Mishkind MC. Legal, regulatory, and risk management issues in the use of technology to delivery mental health care. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2015;22:258–268. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, Nguyen TD. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: Development of a general scale. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1979;2:197–207. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EL, Patton S. Using videoconferencing to deliver individual therapy and pediatric psychology interventions with children and adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2016;26:212–220. doi: 10.1089/cap.2015.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pediatric OCD Treatment Study Team. Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination with children and adolescents with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:1969–1976. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.16.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. Home broadband 2015. 2016 Jun 16; 2015. Retrieved at http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/12/21/2015/Home-Broadband-2015/

- Piacentini J, Bergman L, Jacobs C, McCracken JT, Kretchman J. Open trial of cognitive behavior therapy for childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2002;16:207–219. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6185(02)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 5th. New York: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Scahill L, Riddle MA, McSwiggin-Hardin M, et al. Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: reliability and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(6):844–852. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, et al. A children’s global assessment scale (CGAS) Archives of General Psychiatry. 1983;40(11):1228–1231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Albano AM. The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children for DSM-IV: Child and parent versions. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Caporino NE, Morgan JR, et al. Preliminary investigation of web-camera delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for youth with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2011;189(3):407–412. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wootton BM. Remote cognitive-behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive symptoms: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2016;43:103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]