Abstract

Physical inactivity is a known risk factor for obesity and a number of chronic diseases. Modifying the physical features of neighborhoods to provide residents with equitable and convenient access to spaces for physical activity (PA) is a promising strategy for promoting PA. Public urban recreation spaces (e.g., parks) play an important role in promoting PA and are potentially an important neighborhood element for optimizing social capital and liveability in cities. Most studies examining the effects of park availability and use on PA have focused on traditional, permanent parks. The aims of this study were to (1) document patterns of park use and park-based PA at a temporary urban pop-up park implemented in the downtown business district of Los Altos, California during July–August 2013 and May–June 2014, (2) identify factors associated with park-based PA in 2014, and (3) examine the effects of the 2014 pop-up park on additional outcomes of potential benefit for park users and the Los Altos community at large. Park use remained high during most hours of the day in 2013 and 2014. Although the park attracted a multigenerational group of users, children and adolescents were most likely to engage in walking or more vigorous PA at the park. Park presence was significantly associated with potentially beneficial changes in time-allocation patterns among users, including a reduction in screen-time and an increase in overall park-time and time spent outdoors. Park implementation resulted in notable use among people who would otherwise not be spending time at a park (85% of surveyed users would not be spending time at any other park if the pop-up park was not there—2014 data analysis). Our results (significantly higher odds of spending time in downtown Los Altos due to park presence) suggest that urban pop-up parks may also have broader community benefits, such as attracting people to visit downtown business districts. Pending larger, confirmatory studies, our results suggest that temporary urban pop-up parks may contribute to solving the limited access to public physical activity recreation spaces many urban residents face.

Keywords: Physical activity, Parks and public spaces, Built environment, Pop-up parks, SOPARC

Introduction

Physical inactivity is a global pandemic [1], with about a quarter of the world’s population not meeting physical activity (PA) recommendations [2]. Physical inactivity is a risk factor for obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, dementia, osteoporosis, and some types of cancer [2, 3], and is responsible for significant economic expenditures due to decreased productivity and increased health care costs [4]. Discretionary-time has been identified as a key domain for public health PA promotion efforts due to its modifiable nature [5, 6].

Modifying the physical features of neighborhoods to provide residents with equitable and convenient access to spaces for PA practice is a promising strategy for promoting PA [7]. The availability and use of public recreation spaces in neighborhoods (e.g., local parks) has been positively associated with discretionary-time PA among residents [8]. A recent multi-country study of 14 cities in 10 countries identified park availability as a consistently positive correlate of adult PA across all international sites [9]. In addition, well-kept, safe, and accessible parks are an ideal setting for urban residents to spend time outdoors [10], a behavior that has been directly associated with psychological wellbeing and low risk of vitamin D deficiency across the age range [11–13]. Parks also provide facilities for play, an essential activity for adequate mental and motor development in children [12, 14]. Finally, parks can serve as a setting for social interaction, a core aspect of social capital, and thus have the potential to positively influence the quality of life of individuals and improve livability in cities [10, 15, 16].

The scientific literature has focused primarily on traditional, permanent parks, with little information known about patterns of park use and park-based PA in temporary, urban pop-up parks. Tactical urbanism refers to the use of low-cost, fast, temporary changes to the built environment to “make a small part of a city more enjoyable” and to show residents and decision makers potential improvements to liveability should these changes be permanently adopted [17]. Tactical urbanists define pop-up parks as the “temporary or permanent transformation of underutilized [urban] spaces into community gathering areas through beautification.” [17] A common theme in the emerging topic of pop-up parks is the recovery of public spaces otherwise restricted for motor vehicle use (e.g., streets) [17]. By design, pop-up parks exist in urban areas where a traditional park would seldom be located, such as abandoned or unused land parcels, districts with high land-use mix and foot traffic (e.g., central business districts, entertainment districts), or places with an assigned land-use outside of the realm of nature, public space, or recreation (e.g., parking lots) [18]. Pop-up parks are usually small, ranging in size from a single parking space to a couple of street blocks [18]. The coexistence of an esthetically pleasing, small park with urban features typical of a central business district (e.g., retail shops, restaurants, street intersections, office buildings, pedestrian and car traffic) makes urban pop-up parks a unique setting for discretionary-time PA.

The purpose of this study was to document patterns of park use and levels and correlates of park-based PA at a temporary pop-up park implemented in Los Altos, California during July–August 2013 and May–June 2014. We also examined the effects of the pop-up park on additional potentially beneficial outcomes for park users and the Los Altos community at large.

Methods

Study Design

This study used a serial cross-sectional research design to assess patterns of park use and park-based PA at a temporary urban pop-up park during 2013 (6 weeks, July–August) and 2014 (3.5 weeks, May–June).

Study Setting: Los Altos, California

Los Altos is a city of 30,671 residents in the San Francisco Bay Area [19]. Average household income was $158,444 in 2014 (medium-high, relative to the San Francisco Bay Area) [20]. The majority of residents are white (68%), followed by Asian (24%), mixed race (4%), Latino (4%), and Black (<1%) [19]. The city has nine permanent parks located in predominantly residential neighborhoods. Most of the city’s retail outlets, restaurants, bars, coffee shops, and services are located in the downtown central business district, which is composed of 24 city blocks.

State Street Green: A Natural Intervention

A main street block in the downtown central business district was closed to motor vehicle use due to construction occurring at one of its main access points in summer 2013. The City of Los Altos and a private investment group partnered to install a pop-up park (State Street Green) on the closed street segment (Fig. 1). Further street closures due to construction on the same street segment resulted in the re-installation of the temporary pop-up park in late spring 2014.

Fig. 1.

State Street, in downtown Los, Altos, California, without and during the implementation of the temporary pop-up park: a before pop-up park implementation (photography source—Google Street View), b during pop-up park implementation (photography source—http://passerelleinvestments.com/state-street-green)

The park consisted of two main sections: a green space and a skate park. The green space occupied three quarters of the total park area (8200 ft2). The street surface was covered with artificial grass and had movable lounge chairs, tables, and umbrellas for shade. As park users were able to move the furniture, the green space provided opportunities for children and adolescents to play and for adults to participate in organized activities (e.g., yoga). The skate park covered about a fourth of the total park area and included a small half pipeline and other ramps. Additional park features included a bicycle parking rack and chalk and magnet boards. The park was advertised through the local newspaper. In addition, many residents likely learned about the park by driving, biking, or walking through the downtown central business district and through word of mouth.

Measures

Systematic Observations of Park Use

Overall park use and proportion of active park users were measured using the System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities (SOPARC). SOPARC is a widely accepted direct observation instrument to measure PA and user characteristics (sex, age group, and race/ethnicity) in community settings (e.g., parks) [21, 22]. SOPARC utilizes momentary time-sampling approaches to document park use throughout the day [22, 23]. The two main sections of the park (the green space and skate park) were designated as target areas for observation. Each target area was divided into sub-target areas when needed to ensure the accurate measurement of PA and user characteristics. The validity and reliability of the SOPARC to objectively measure PA and user characteristics in community settings has been reported elsewhere [22].

Raters were trained in SOPARC data collection by study authors (D.S. and J.B.) with experience using the SOPARC and other direct observation instruments. Rater training consisted of a 1-day in-class session, using presentations and the online SOPARC videos, and a series of field-based practice sessions over the course of 1 week. Raters had high inter-rater reliability for total number of park users (ICCs > 0.90) and number of park users by sex, age group, and race/ethnicity (ICCs > 0.80).

As counters were not available for data collection, raters tracked park user characteristics when conducting a target area scan, keeping their focus on the target area during the observation. Raters then entered data onto SOPARC observation forms after the target area observation scan was complete. To allow for accurate counts and observation of user’s characteristics, the two main target areas (green space and skate park) were subdivided into smaller sub-target areas when the park was too crowded. Other researchers have successfully used this approach when counters are unavailable [24]. For each data collection period (2013 and 2014), SOPARC observations were conducted on two randomly selected weekdays, and one Saturday and one Sunday during a randomly selected week. SOPARC observations were conducted every hour from 7 am to 8 pm on each observation day. The SOPARC target area coding form was used in 2013 (year 1), providing an independent count of female and male park users. The SOPARC path coding form was used in 2014 (year 2), providing information on each park user’s sex, age group, race/ethnicity, and activity level. Others have successfully employed similar approaches for the purpose of linking momentary assessments of PA with detailed sociodemographic characteristics of observed park users [21, 25].

Park use was determined for each observation period by summing the number of park users observed. The number of physically active users per observation period was determined by summing the number of park users engaged in SOPARC walking and greater intensity activities.

Intercept Surveys of Park Use

Data collectors also were trained to administer intercept surveys to park users from 7 am to 8 pm on SOPARC observation days. Park users were defined as anyone located on the green space or skate park at the time of data collection. Intercept surveys were administered to child, adolescent, and adult park users. Surveys were interviewer-administered in English, with data collection taking place between hourly SOPARC observations. Data collectors approached child and adolescent park users only if an adult accompanied the child or adolescent. Data collectors obtained verbal consent from a parent/guardian and verbal assent from the child/adolescent when administering intercept surveys to children and adolescents. Data collectors obtained verbal consent from adults when administering an intercept survey to an adult. The study protocol and consent process was determined to be appropriate by the Institutional Review Board at Stanford University. Protected health information and personally identifiable information was not collected in this study.

Frequency and duration of park use were derived from the following intercept-survey items: “Since its opening, how many times have you been to the park? Make sure to include today’s visit in your response” (frequency) and “How much time will you spend at the park today? Include the total time since you arrived until you plan to leave” (duration). Minutes per week of pop-up park use were derived from these intercept-survey items.

Alternate activities in which park users would have engaged in if the park was not present was determined from the following survey item: “What would you be doing at this time of the day if the pop-up park wasn’t here?” Each open-ended response was coded into a series of non-exclusive, dichotomous (yes/no) categories: screen-time (television viewing or computer use) versus non screen-time, spending time in a park versus spending time elsewhere, spending time in downtown Los Altos versus spending time elsewhere, and outdoor time versus indoor time. Data collectors recorded the respondent’s sex, age group (child, adolescent, adult, older adult), and race/ethnicity (white, Black, Latino, Asian, other), based on direct observation.

Analysis

Descriptive Statistics: 2013 and 2014 Data

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize SOPARC data collected in 2013 and 2014. Total number of park users and number of park users by sex were determined for each 4-day observation period. Number and percent of park users by age group, race/ethnicity, park target area (green space vs. skate park), type of day (weekend vs. weekday), and activity level [sedentary, walking, and vigorous activity, defined as any activity more intensive than walking (per SOPARC’s scoring protocol)] were calculated. The average number of total and physically active park users and their distribution by age group were calculated by time of day.

Regression Analyses: 2014 Data

SOPARC data were used to identify sociodemographic and contextual factors associated with moderate-to-vigorous intensity PA among users. Only 2014 data were used for this analysis as they were collected using the SOPARC Path form, which was used to document each park user’s sex, age group, race/ethnicity, and activity level. Unadjusted (bivariate) and adjusted (multivariate) logistic regression models were fit to estimate the association of sex, age, race/ethnicity, type of day (weekend vs. weekday), and park target area (green space vs. skate park) with engagement in walking or vigorous activities at the park.

Survey-based 2014 data were used to estimate the effect of park availability on the odds of spending ≥30 min per week on alternate activities of interest (spending time in downtown Los Altos, spending time outdoors, spending time at a park, and spending time in front of a screen). First, the prevalence of each alternate activity category was determined. Next, we calculated minutes per week spent at the park using reported frequencies and duration of park use, and assigned those values to the alternate activities being substituted by park use. Multivariate logistic regression models were fit to estimate the effect of pop-up park availability (independent variable) on spending ≥30 min per week on each alternate activity of interest (dependent variables). All models were adjusted for the effects of sex, age group, and race/ethnicity. Because the survey item assessing frequency of pop-up park use was only available in the 2014 survey, only year 2 survey data were used. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.3. Statistical significance was defined as p <0.05.

Results

Characterization of Pop-Up Park use in 2013 and 2014

Number of park users by year, sociodemographic, and contextual characteristics are presented in Table 1. More park users were observed during 2014 than 2013 (2116 vs. 1770). A greater proportion of park users were observed on the green space (96.9% in 2013, 86.2% in 2014) than the skate park. About half of park users were female (55.6% in 2013, 51.3% in 2014). Most park users were adults (48.1% in both years) and children (40.3% in 2013, 32.0% in 2014). More adolescents used the park in 2014 (13.4%) than in 2013 (5.3%), with skate park use greater in 2014 (13.8%) than 2013 (3.1%). Park use was greater during weekends in 2013 (weekend park users, 53.7%; weekday park users, 46.3%), while the inverse was observed in 2014 (weekend park users, 46.3%; weekday park users, 53.7%).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and contextual characterization of pop-up park use, and physical activity among pop-up park users, Los Altos, California, 2013 and 2014

| Female | Male | Total | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2014 | 2013 | 2014 | 2013 | 2014 | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Demographics | ||||||||||||

| Age group | ||||||||||||

| Children | 371 | 37.7 | 337 | 31.4 | 342 | 43.5 | 335 | 32.7 | 713 | 40.3 | 672 | 32.0 |

| Adolescents | 51 | 5.2 | 117 | 10.9 | 42 | 5.3 | 165 | 16.1 | 93 | 5.3 | 282 | 13.4 |

| Adults | 506 | 51.4 | 547 | 50.9 | 345 | 43.9 | 463 | 45.2 | 851 | 48.1 | 1010 | 48.1 |

| Older Adults | 56 | 5.7 | 73 | 6.8 | 57 | 7.3 | 61 | 6.0 | 113 | 6.4 | 134 | 6.4 |

| Total | 984 | 100.0 | 1074 | 100.0 | 786 | 100.0 | 1024 | 100.0 | 1770 | 100.0 | 2098 | 100.0 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| White | 667 | 72.7 | 797 | 74.6 | 543 | 77.0 | 841 | 81.9 | 1210 | 74.6 | 1638 | 78.1 |

| Black | 15 | 1.6 | 25 | 2.3 | 4 | 0.6 | 19 | 1.9 | 19 | 1.2 | 44 | 2.1 |

| Latino | 24 | 2.6 | 43 | 4.0 | 29 | 4.1 | 30 | 2.9 | 53 | 3.3 | 73 | 3.5 |

| Asian | 157 | 17.1 | 167 | 15.6 | 97 | 13.8 | 108 | 10.5 | 254 | 15.7 | 275 | 13.1 |

| Other | 54 | 5.9 | 37 | 3.5 | 32 | 4.5 | 29 | 2.8 | 86 | 5.3 | 66 | 3.1 |

| Total | 917 | 100.0 | 1069 | 100.0 | 705 | 100.0 | 1027 | 100.0 | 1622 | 100.0 | 2096 | 100.0 |

| Context | ||||||||||||

| Type of day | ||||||||||||

| Weekday | 483 | 49.1 | 683 | 62.9 | 337 | 42.9 | 454 | 44.0 | 820 | 46.3 | 1137 | 53.7 |

| Weekend | 501 | 50.9 | 402 | 37.1 | 449 | 57.1 | 577 | 56.0 | 950 | 53.7 | 979 | 46.3 |

| Total | 984 | 100.0 | 1085 | 100.0 | 786 | 100.0 | 1031 | 100.0 | 1770 | 100.0 | 2116 | 100.0 |

| Park area | ||||||||||||

| Green space | 980 | 99.6 | 1009 | 93.0 | 736 | 93.6 | 814 | 79.0 | 1716 | 96.9 | 1823 | 86.2 |

| Skate park | 4 | 0.4 | 76 | 7.0 | 50 | 6.4 | 217 | 21.0 | 54 | 3.1 | 293 | 13.8 |

| Total | 984 | 100.0 | 1085 | 100.0 | 786 | 100.0 | 1031 | 100.0 | 1770 | 100.0 | 2116 | 100.0 |

| Physical activity | ||||||||||||

| Sedentary | 772 | 79.8 | 746 | 69.5 | 549 | 77.4 | 660 | 64.3 | 1321 | 78.8 | 1406 | 67.0 |

| Walking | 135 | 14.0 | 242 | 22.5 | 98 | 13.8 | 230 | 22.4 | 233 | 13.9 | 472 | 22.5 |

| Vigorous | 60 | 6.2 | 86 | 8.0 | 62 | 8.7 | 136 | 13.3 | 122 | 7.3 | 222 | 10.6 |

| Total | 967 | 100.0 | 1074 | 100.0 | 709 | 100.0 | 1026 | 100.0 | 1676 | 100.0 | 2100 | 100.0 |

Total park use may not be equal across demographic, context, and physical activity characteristics due to the momentary time sampling approaches used in this study

PA at the Pop-Up Park in 2013 and 2014

The proportion of park users engaged in moderate to vigorous PA was greater in 2014 (33.1%) than 2013 (21.2%). A greater proportion of males than females were physically active at the park in 2013 [20.1% active females vs. 22.6% active males (χ 2 = 2.1; p = 0.15)] and 2014 [30.5% active females vs. 35.7% active males (χ 2 = 6.0; p = 0.01)].

Overall and Active Pop-Up Park Use by Time of Day

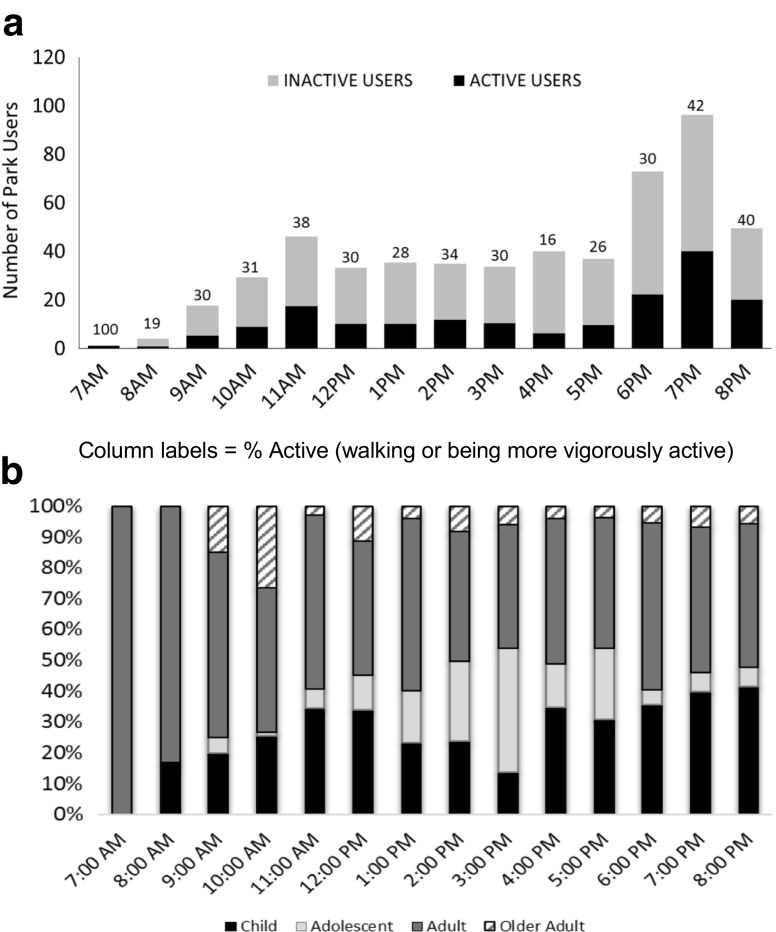

This section only presents results from 2014 given similar daily patterns of use by time of day observed in 2013 and 2014, and to avoid pooling of data from two data collection periods. Mean park use was highest in the evenings (6 pm to 8 pm), with 50 to 96 park users per hour (Fig. 2). In contrast, mean number of park users was lowest during the early mornings (7 am to 9 am), with 1 to 18 users per hour. Finally, park use was relatively constant between 10 am and 5 pm, with 29 to 46 park users per hour.

Fig. 2.

Distribution by time of day of a average total and physically active pop-up park users, and b percentage users by age group, Los Altos, California, 2014

The 7 am time period (proportion active, 100%) had the highest proportion of physically active users; however, the small number of total park users at that time (4 people per hour) reduces the meaningfulness of this observation. The 11 am (proportion active, 38%), 7 pm (proportion active, 42%), and 8 pm (proportion active, 40%) time periods had the next highest proportions of physically active users. These time periods correspond to times of the day with higher proportions of child and adolescent park users (Fig. 2). In contrast, 8 am (proportion active, 19%) and 4 pm (proportion active, 16%) had the lowest proportion of active users. In general, higher total number of park users and a higher proportion of child park users yielded higher proportions of active park users.

Sociodemographic and Contextual Characteristics Associated with Walking or More Intensive PA at the Pop-Up Park in 2014

Unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression analysis to identify sociodemographic and contextual correlates of walking or more intensive PA at the park using 2014 data are presented in Table 2. Results from the fully adjusted models show that being male [vs. female; odds ratio (OR) = 1.2; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.0, 1.5], a child or adolescent (vs. adult; child—OR = 3.7; 95% CI = 3.0, 4.6; adolescent—OR = 1.5; 95% CI = 1.1, 2.0), and a skate park user (vs. green space user; OR = 3.1, 95% CI = 2.3, 4.2) were independently and positively associated with being a physically active pop-up park user (vs. being a sedentary park user). Meanwhile, being a weekend user (vs. a weekday user) was inversely associated with the odds of being physically active at the park (OR = 0.4, 95% CI = 0.3, 0.5). Race/ethnicity was not a significant correlate of PA at the park.

Table 2.

Demographic and contextual factors associated with moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activitya among pop-up park users, Los Altos, California, 2014

| Independent variables | Unadjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | Adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Male | 1.3 (1.1, 1.5)* | 1.2 (1.0, 1.5)* |

| Age group | ||

| Adult (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Child | 3.8 (3.1, 4.7)* | 3.7 (3.0, 4.6)* |

| Adolescent | 1.6 (1.2, 2.2)* | 1.5 (1.1, 2.0)* |

| Older adult | 1.1 (0.7, 1.7) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.6) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Latino | 0.9 (0.6, 1.6) | 1.1 (0.6, 1.9) |

| Black | 1.1 (0.6, 2.0) | 1.4 (0.7, 2.8) |

| Asian | 1.2 (0.9, 1.6) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.4) |

| Other | 1.1 (0.7, 1.9) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.8) |

| Park area used at time of observation | ||

| Green space (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Skate park | 2.1 (1.6, 2.6)* | 3.1 (2.3, 4.2)* |

| Type of day | ||

| Weekday (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Weekend | 0.6 (0.5, 0.7)* | 0.4 (0.3, 0.5)* |

*p < 0.05

aThis is a binary variable including activities coded as “walking” or “vigorous” per SOPARC’s scoring protocol. This variable does not include frequency or duration: it is a snapshot of the observed activity intensity during the 12-hourly observation periods of the 4 randomly selected days of observation

Association of Park Availability with Time Spent in Alternate Activities in 2014

The 2014 intercept-survey sample size was 147 users, with a response rate of 97.4%. Of intercept-survey responders, 62.3% were female, 61.9% were adults, 12.9% were older adults, 19.1% were adolescents, and 6.1% were children. The majority of survey respondents were white (74.5%), followed by Asian (18.6%).

The majority (58.5%) of park users who completed the survey reported that if the park were not available, they would not be in downtown Los Altos at the time of survey administration. In addition, 32.7% of park users reported they would be spending time at an indoor location, 64.6% reported they would be spending time in front of a screen (watching television, at the movies, using a computer or tablet, or playing videogames), while 15.0% reported they would be at another park. These percentages do not sum to 100% as the analytic categories were not mutually exclusive. Rather, each respondent’s alternate activities were re-coded as dichotomous categories for statistical analysis: being in downtown Los Altos versus being elsewhere, being outdoors versus being indoors, being at a park versus being elsewhere, and spending time in front of a screen versus not spending time in front of a screen.

The results of the adjusted logistic regression models to estimate the effect of pop-up park availability on time spent in alternate activities are shown in Table 3. Pop-up park availability in 2014 was significantly and positively associated with the odds of spending ≥30 min per week in downtown Los Altos (OR = 1.5; 95% CI = 1.2, 2.0), outdoors (OR = 2.0; 95% CI = 1.5, 2.8), and at a park (OR = 1.6; 95% CI = 1.2, 2.0). Meanwhile, pop-up park availability was inversely associated with the odds of spending ≥30 min per week in front of a screen (OR = 0.2; 95% CI = 0.1, 0.5).

Table 3.

Effect of pop-up park availability on the odds of spending 30 min per week or more on alternate activities, among pop-up park users, Los Altos, 2014

| Alternate activities (dependent variable) | Odds of spending ≥30 min/week on alternate activity (independent variable) Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|

| Spending ≥30 min/week in downtown Los Altos | 1.5 (1.2, 2.0)* |

| Spending ≥30 min/week outdoors | 2.0 (1.5, 2.8)* |

| Spending ≥30 min/week at a park | 1.6 (1.2, 2.0)* |

| Spending ≥30 min/week in front of a screena | 0.2 (0.1, 0.5)* |

All logistic regression models are adjusted for the effect of sex, age, and race/ethnicity

*p < 0.05

aIncludes reporting watching television, movies, using a computer or tablet, and playing videogames

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine patterns of temporary, urban pop-up park use. Our results indicate that the implementation of a pop-up park in the heart of a downtown shopping district in a small urban city resulted in notable use among people who would otherwise not be spending time at a park (85% of surveyed users reported that they would not be spending time at any other park if the pop-up park was not there). Throughout both implementation periods, park use remained high during most hours of the day. Although the park attracted a multigenerational group of users, children and adolescents were most likely to engage in walking or more vigorous PA at the park. An important contribution of this study was the exploration of potential co-benefits of urban pop-up parks use beyond PA, with beneficial changes in time-allocation patterns among users as a result of pop-up park availability.

Park use appeared to be greater at this small, urban temporary park (0.2 acres; 442–529 users/day) than in larger (>8 acres) traditional parks [23, 26]. Children were the most active park users in this study. This finding is consistent with results from studies examining use in traditional, larger permanent parks [21, 26], and a study that identified access to small pocket parks as being conducive to increased levels of moderate to vigorous PA among children [27].

A substantial increase was observed in the proportion of active adolescents from 2013 to 2014. One potential explanation is the wider range of open skate park hours during this second year of pop-up park implementation. Our results showed that skate park users (mostly children and adolescents) had higher odds of being active than green space users. This finding underscores the importance of certain park features for promoting PA among youth [28–30]. Other cities considering the implementation of pop-up parks and aiming to attract youth should consider implementing similar targeted design strategies.

In addition to targeted design strategies, it has been suggested that “place activation” (the provision of organized activities in public places) could help enhance active park use [31]. Several structured, organized activities were offered at the park at different time points, mainly during the first year of implementation, and most targeting young children (e.g., directed play, storytelling). Meanwhile, fewer structured activities were offered during the second implementation period (2014). The substantial increase observed in the proportion of active users from 2013 to 2014 (12% increase, χ 2 = 65.7, p ≤ 0.0001) suggests that structured activities may not be essential for maximizing active use of pop-up parks. This may be due to the small size of the park in this study, which lends itself better to free play among young children than to crowded organized events. It is also possible that the lack of child-focused, structured activities at the green space during 2014 contributed to greater use by adolescents. However, the provision of well-targeted structured activities may be important to attract other population subgroups (e.g., older adults, racial/ethnic minorities), as well as enhance community interaction and social cohesion in urban centers [32, 33]. The availability of structured activities has been reported as an important feature for park use and park-based PA in a nationally representative study of parks in the USA [26]. Place activation has also been identified as critical in other natural interventions involving urban space transformations for PA promotion. For example, the Ciclovia Recreativa program in Bogotá, Colombia, involves closing major city streets every Sunday to motor vehicles, and encourages walking, bicycling, and organized recreational activities in their place [34, 35]. A recent study from Bogotá, Colombia, reported that parks and plazas without “place activation” had lower attendance than their “place-activated” counterparts [36]. Future studies should examine the effects of targeted place activation on increasing active pop-up park use among specific population subgroups.

Unexpectedly, weekday park users were more likely to be physically active at the pop-up park than weekend users. This is in contrast to a previous study examining park use in larger permanent parks in the nearby city of San Francisco, California, where no significant differences were observed between park-based PA on weekdays versus weekends [37]. An investigation in the UK also reported greater park-based PA during weekends among children when permanent parks were studied [38]. The present study’s 2013 temporary park was implemented during July–August; hence, children and adolescents (the most active pop-up park users) were in their school summer vacation period and could spend weekdays at the park. Of note, however, is that when the temporary park was implemented in May–June 2014, children and adolescents were still in school, and high levels of park-based PA were still observed among youth. Given that our statistical models (Table 2) were adjusted for age group, this potential interpretation can thus be discarded as the driving factor underlying the relation between type of day (weekday vs. weekend) and park-based PA. Further research is needed to elucidate this finding.

The results indicate that the presence of a temporary park in the heart of the downtown shopping district was associated with potentially beneficial changes in time-allocation patterns among users, including a significant reduction in screen-time and a significant increase in overall park-time. Our exploratory analysis examining the effect of park availability on park users’ time-allocation patterns also suggests that the presence of public recreation spaces in urban settings may have benefits beyond health behaviors. Our results (a higher odds of spending time downtown, with 58% of park users reporting they would not be in the central business district if the park were not there) indicate that urban, temporary parks may have potential to become important contributors in the revitalization of downtown central business districts. While others have examined similar societal benefits in traditional and small-scale natural parks [39–41], we believe this study is the first to explore these types of outcomes in temporary, urban, pop-up parks.

This study has limitations that should be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design precluded determinations of causality. The results may not be generalizable to other pop-up parks with varying geographic and area-level socioeconomic characteristics; the park in this study was located in a small and affluent community in the San Francisco Bay Area. Further, the present study measured PA patterns and administered intercept surveys only among park users. Future studies should consider utilizing a representative sample of residents from the park’s surrounding community to determine differences in PA levels between users and non-users. The use of the SOPARC path coding form in 2014 and the SOPARC target area observation form in 2013 may limit the comparability of our results with previous studies [42]. As others have done, we opted for this change in 2014 to allow for individual-level analysis of factors associated with park-based PA [24, 25]. On the other hand, the flexibility of SOPARC for adaptation to different study needs has been highlighted as a strength [43]. Data in 2013 and 2014 were collected in different months. While weather conditions were fairly stable in Los Altos, CA, during both years and across both time periods [44], as is typical of this region of California, other aspects such as youth sports seasons and school vacation periods may have had unknown effects on park use. Our analysis examining the effects of the pop-up park on the time allocated to alternate activities should be considered exploratory, as several factors were not controlled for in the analysis. In particular, we were not able to adjust for variations in daily patterns of activity outside of the park-use period. In addition, although we based the intercept survey on a previously validated instrument [45], the item used to assess what park users would be doing if the park were not present has not been tested for validity or reliability. Further, weekly minutes of park use were estimated assuming the same duration for each reported park visit (frequency) as the reported duration on the survey administration day. Larger, prospective studies using activity diaries to account for total daily time-allocation patterns are warranted to confirm our findings.

This study also has several strengths. It is, to our knowledge, the first to examine patterns of total park use and PA at a temporary, urban pop-up park. This study also used a mixed-methods approach that combined objective and self-report measures to characterize park use. In addition, direct observations of park use occurred every hour from 7 am to 8 pm, which is greater than the typical three to four daily momentary samples done in other studies [25, 46]. This high frequency observation protocol provided a detailed and accurate representation of park use. Further, we had a very high intercept-survey response rate (97.4%). Finally, examining of the effects of park availability on co-benefits beyond health behaviors, including time spent in the downtown central business district, may provide useful information for policy makers, urban planners, and local businesses and residents with respect to the potential contributions beyond health-related outcomes of small, temporary urban parks. The potential role of urban pop-up parks in building social capital and increasing foot traffic in downtown central business districts warrants further study.

Pending larger, confirmatory studies, our results suggest that the creation of temporary urban pop-up parks may be beneficial for small communities such as downtown Los Altos, CA. Pop-up parks show promise of being a relatively easy, inexpensive, and potentially scalable solution to the limited access of public recreation spaces for PA that many urban residents face. Permanent urban transformations typically are costly and require several years for full implementation. However, pop-up parks challenge the notion that urban spaces are permanent in nature—the same space that is a street block for motor vehicles to drive through one day can easily become a vibrant urban park the following day, where children and adolescents can be physically active while adults connect with each other. Such “natural interventions” deserve further study [47, 48], given their potential for providing additional avenues for promoting PA as well as social capital and quality of life in urban settings.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Martell Hesketh and Nkeiruka Umeh for their work as data collectors for this study. We also thank the City of Los Altos, Passarelle Investments, and pop-up park users who responded to our survey.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Funding

This study had no financial funding source. At the time the study took place, D.S. and A.C.K. received partial support from US Public Health Service Grant 1R01HL109222 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. J.A.B., J.L.S., and S.J.W. received support from US Public Health Service Grant 5T32HL007034 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. D.L.d.S. was supported by the Brazil Scientific Mobility Scholarship Program of Brazil’s Ministry of Education and Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation. At time of manuscript preparation, D.S. was supported by US Public Health Service Grant Diversity Supplement training grant 3R01DK101593-03S1 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

References

- 1.Kohl HW, 3rd, Craig CL, Lambert EV, et al. The pandemic of physical inactivity: global action for public health. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):294–305. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60898-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sallis JF, Bull F, Guthold R, et al. Progress in physical activity over the Olympic quadrennium. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1325–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30581-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, et al. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):219–229. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ding D, Lawson KD, Kolbe-Alexander TL, et al. The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1311–1324. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30383-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore SC, Patel AV, Matthews CE, et al. Leisure time physical activity of moderate to vigorous intensity and mortality: a large pooled cohort analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9(11):e1001335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pettee Gabriel KK, Morrow JR, Jr, Woolsey AL. Framework for physical activity as a complex and multidimensional behavior. J Phys Act Health. 2012;9(Suppl 1):S11–S18. doi: 10.1123/jpah.9.s1.s11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sallis JF, Glanz K. Physical activity and food environments: solutions to the obesity epidemic. Milbank Q. 2009;87(1):123–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaczynski AT, Besenyi GM, Stanis SA, et al. Are park proximity and park features related to park use and park-based physical activity among adults? Variations by multiple socio-demographic characteristics. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11:146. doi: 10.1186/s12966-014-0146-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sallis JF, Cerin E, Conway TL, et al. Physical activity in relation to urban environments in 14 cities worldwide: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2016;387(10034):2207–2217. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01284-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Blasio B. Healthier neighbourhoods through healthier parks. Lancet. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Ergler CR, Kearns RA, Witten K. Seasonal and locational variations in children’s play: implications for wellbeing. Soc Sci Med. 2013;91:178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCurdy LE, Winterbottom KE, Mehta SS, Roberts JR. Using nature and outdoor activity to improve children’s health. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2010;40(5):102–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Traynor V, Fernandez R, Caldwell K. The effects of spending time outdoors in daylight on the psychosocial wellbeing of older people and family carers: a comprehensive systematic review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2013;11(9):36–55. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2013-1065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herrington S, Brussoni M. Beyond physical activity: the importance of play and nature-based play spaces for children’s health and development. Curr Obes Rep. 2015;4(4):477–483. doi: 10.1007/s13679-015-0179-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaźmierczak A. The contribution of local parks to neighbourhood social ties. Landsc Urban Plan. 2013;109(1):31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Southworth M. Learning to make liveable cities. J Urban Des. 2016;21(5):570–573. doi: 10.1080/13574809.2016.1220152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.COLLABOARATIVE SP. Tactical urbanism, short-term action II long-term change. Miami/New York: Street Plans Collaborative; 2011.

- 18.Bison. A Guide to Pop-Up Parks. 2013; http://www.bisonip.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/PopUpParksGuide-2013.pdf. Accessed Dec 10, 2016, 2016.

- 19.US Census Bureau. United States Census Bureau, Population Estimates Program (PEP), July 1, 2015 (V2015). 2015; http://www.census.gov/popest/. Accessed Dec 10, 2016, 2016.

- 20.US Census Bureau. American Community Survey (ACS) and Puerto Rico Community Survey (PRCS), 5-Year Estimates. 2015; https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml. Accessed Dec 10, 2016.

- 21.Evenson KR, Jones SA, Holliday KM, Cohen DA, McKenzie TL. Park characteristics, use, and physical activity: a review of studies using SOPARC (System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities) Prev Med. 2016;86:153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKenzie TL, Cohen DA, Sehgal A, Williamson S, Golinelli D. System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities (SOPARC): reliability and feasibility measures. J Phys Act Health. 2006;3(Suppl 1):S208–S222. doi: 10.1123/jpah.3.s1.s208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen DA, Setodji C, Evenson KR, et al. How much observation is enough? Refining the administration of SOPARC. J Phys Act Health. 2011;8(8):1117–1123. doi: 10.1123/jpah.8.8.1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murcia M, Rivera MJ, Akhavan-Tabatabaei R, Sarmiento OL. A discrete-event simulation model to estimate the number of participants in the ciclovia program of Bogota. Paper presented at: Simulation Conference (WSC), 2014 Winter2014.

- 25.Bocarro JN, Floyd M, Moore R, et al. Adaptation of the System for Observing Physical Activity and Recreation in Communities (SOPARC) to assess age groupings of children. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6(6):699–707. doi: 10.1123/jpah.6.6.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen DA, Han B, Nagel CJ, et al. The first national study of neighborhood parks: implications for physical activity. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(4):419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen DA, Marsh T, Williamson S, et al. The potential for pocket parks to increase physical activity. Am J Health Promot: AJHP. 2014;28(3 Suppl):S19–S26. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.130430-QUAN-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rung AL, Mowen AJ, Broyles ST, Gustat J. The role of park conditions and features on park visitation and physical activity. J Phys Act Health. 2011;8(2):S178. doi: 10.1123/jpah.8.s2.s178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaczynski AT, Potwarka LR, Saelens BE. Association of park size, distance, and features with physical activity in neighborhood parks. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1451–1456. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.129064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ries AV, Voorhees CC, Roche KM, Gittelsohn J, Yan AF, Astone NM. A quantitative examination of park characteristics related to park use and physical activity among urban youth. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(3):S64–S70. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGlone N. Pop-up kids: exploring children’s experience of temporary public space. Australian Planner. 2016;53(2):117–126. doi: 10.1080/07293682.2015.1135811. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pittard A. Rockingham Arts Centre: from ambulance depot to community arts centre-transformed. Australasian Parks and Leisure. 2013;16(4):13. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Layard A. Property paradigms and place-making: a right to the city; a right to the street? J Hum Rights Environ. 2012;2:254–272. doi: 10.4337/jhre.2012.03.04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarmiento OL, Díaz del Castillo A, Triana CA, Acevedo MJ, Gonzalez SA, Pratt M. Reclaiming the streets for people: insights from Ciclovías Recreativas in Latin America. Preventive Medicine. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Sarmiento O, Torres A, Jacoby E, Pratt M, Schmid TL, Stierling G. The Ciclovía-Recreativa: a mass-recreational program with public health potential. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7(2):S163. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.s2.s163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Torres A, Díaz MP, Hayat MJ, et al. Assessing the effect of physical activity classes in public spaces on leisure-time physical activity: “Al Ritmo de las Comunidades” A natural experiment in Bogota, Colombia. Prev Med. 2016; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Tester J, Baker R. Making the playfields even: evaluating the impact of an environmental intervention on park use and physical activity. Prev Med. 2009;48(4):316–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lachowycz K, Jones AP, Page AS, Wheeler BW, Cooper AR. What can global positioning systems tell us about the contribution of different types of urban greenspace to children’s physical activity? Health Place. 2012;18(3):586–594. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peters K, Elands B, Buijs A. Social interactions in urban parks: stimulating social cohesion? Urban For Urban Green. 2010;9(2):93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2009.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baur JW, Tynon JF. Small-scale urban nature parks: why should we care? Leis Sci. 2010;32(2):195–200. doi: 10.1080/01490400903547245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lloyd K, Auld C. Leisure, public space and quality of life in the urban environment. Urban Policy Res. 2003;21(4):339–356. doi: 10.1080/0811114032000147395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKenzie TL, Van Der Mars H. Top 10 research questions related to assessing physical activity and its contexts using systematic observation. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2015;86(1):13–29. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2015.991264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McKenzie TL. Context matters: systematic observation of place-based physical activity. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2016;87(4):334–341. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2016.1234302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weather Underground. Weather Underground—Weather History & Data. 2013–2014; https://www.wunderground.com/history/. Accessed November 1, 2016.

- 45.Troped PJ, Whitcomb HA, Hutto B, Reed JA, Hooker SP. Reliability of a brief intercept survey for trail use behaviors. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6(6):775–780. doi: 10.1123/jpah.6.6.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Banda JA, Wilcox S, Colabianchi N, Hooker SP, Kaczynski AT, Hussey J. The associations between park environments and park use in southern US communities. J Rural Health. 2014;30(4):369–378. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reis RS, Salvo D, Ogilvie D, et al. Scaling up physical activity interventions worldwide: stepping up to larger and smarter approaches to get people moving. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1337–1348. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sallis JF, Bull F, Burdett R, et al. Use of science to guide city planning policy and practice: how to achieve healthy and sustainable future cities. Lancet. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]