Abstract

Enteroviruses cause a wide spectrum of clinical disease. In this study, we describe the case of a young man with orchitis and aseptic meningitis who was diagnosed with enterovirus infection. Using unbiased “metagenomic” massively parallel sequencing, we assembled a near-complete viral genome, the first use of this method for full-genome viral sequencing from cerebrospinal fluid. We found that the genome belonged to the subgroup echovirus 30, which is a common cause of aseptic meningitis but has not been previously reported to cause orchitis.

Keywords: enterovirus, meningitis, metagenomics, orchitis

CASE

A previously healthy man in his 20s developed unilateral testicular pain and swelling. Four days later, he developed headache and fever. He presented to our institution, where he was febrile to 102.7°F with mild meningismus; testicular swelling and tenderness had resolved. The combination of symptoms raised concern for mumps in the setting of a local outbreak, although parotitis was absent. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed 17 total nucleated cells/µL (79% neutrophils, 12% monocytes, 9% lymphocytes), glucose of 65 mg/dL (serum glucose of 109 mg/dL), and total protein of 31 mg/dL. He was treated empirically with vancomycin, ceftriaxone, and acyclovir. Cerebrospinal fluid enterovirus polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was positive, antimicrobials were discontinued, and the patient recovered fully. Mumps serology was positive for immunoglobulin (Ig)G and negative for IgM, consistent with his reported history of vaccination. A urine culture for mumps performed by the Massachusetts Department of Health State Laboratory was negative. Cerebrospinal fluid Gram stain and culture were negative, as were CSF herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 PCR, Lyme PCR, and testing for syphilis via the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test. Given the relatively unusual presentation of orchitis and meningitis, we performed metagenomic sequencing to obtain additional genomic information about the particular strain of enterovirus and to identify any potential copathogens including mumps virus.

METHODS

We performed metagenomic sequencing and enterovirus genome assembly using methods developed and validated by our group [1, 2]. Full methods are described in the Supplementary Appendix.

RESULTS

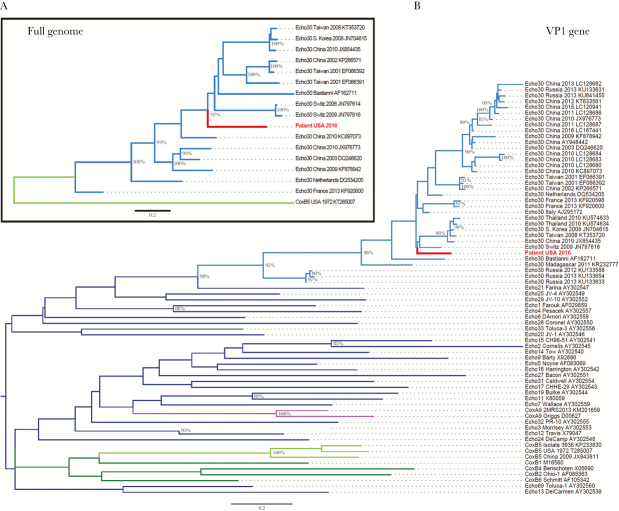

Unbiased metagenomic sequencing allows detection of any potential pathogens in a sample. We performed metagenomic analysis of all sequencing reads from this patient’s CSF and identified enterovirus; no other pathogen, including mumps virus, was found. We assembled a near-full-length enterovirus genome (7212 base pair [bp], median depth of coverage 10×), which included the 5’-untranslated region (UTR) and near-complete coding region, but not the 3’ end (21 bp) of the coding region or the 3’-UTR. By comparing this genome to published enterovirus genomes, we found that this virus belongs to echovirus subgroup 30 (Figure 1A), a member of the highly diverse enterovirus B species group, which includes most echoviruses, coxsackie B viruses, and coxsackie A9 virus [3].

Figure 1.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees of (A) full-length enterovirus genomes and (B) the VP1 gene. (A) The full-length genome sequence identified in this study (“Patient USA 2016”, labeled in red) clusters with sequences belonging to the echovirus 30 subgroup (labeled in light blue). For reference, 1 coxsackie B5 sequence is included (labeled in light green). (B) The VP1 sequence identified in this study (Patient USA 2016, labeled in red) clusters with echovirus 30 sequences (labeled in light blue). Reference VP1 sequences are included from 35 subtypes representing human enterovirus B species: coxsackie B5 (labeled in light green), other coxsackie B subgroups (labeled in dark green), coxsackie A9 (labeled in purple), and other echovirus subgroups (labeled in dark blue). In both trees, branches are named with the enterovirus subtype and location and date of sequence acquisition (clinical samples) or name of reference strain (viral isolates), as well as GenBank accession number. Trees were constructed with 1000 bootstrap replicates, and nodes with at least 80% support are labeled with percent bootstrap support.

Echovirus 30 has not previously been associated with orchitis, but other enteroviruses have, including echovirus 6 [4] and coxsackieviruses A9 and B [5, 6]. Therefore, we investigated whether the virus we identified was a recombinant between echovirus 30 and a subgroup that is more commonly associated with orchitis, because recombination between enteroviruses occurs frequently [3]. We first examined the VP1 gene, which encodes a capsid protein that interacts with host cell receptors and may therefore confer tropism for specific tissue such as the testes. In phylogenetic analysis of the VP1 gene, our virus again clustered with echovirus 30, rather than a subgroup more commonly associated with orchitis (Figure 1B). In the 4 kb at the 3’ end of the genome, we observed similarity between our genome and coxsackievirus B5 (Supplementary Figure 1A) but did not observe specific evidence of recombination in this region (Supplementary Text and Supplementary Figure 1B).

DISCUSSION

Echovirus 30 is one of the most common causes of aseptic meningitis worldwide. Different lineages of echovirus 30 have been linked to geotemporally distinct outbreaks [7–9]. This is the first report of echovirus 30 infection associated with orchitis, although it has been reported with other enteroviruses. Relatively few infectious agents have been described to present with both orchitis and meningitis (Table 1). Although it is interesting to speculate that the strain we identified may possess characteristics associated with testicular tropism, we were unable to formally assess this possibility because the virus examined was from CSF and not testicular tissue. It is also possible, although unlikely, that the patient experienced 2 distinct infections, first with mumps or another pathogen causing orchitis, and subsequently with enterovirus causing meningitis.

Table 1.

Infectious Causes of Orchitis in the Setting of Central Nervous System (CNS) Infection

| Pathogens Reported in Concurrent Orchitis and CNS Infection | Pathogens Affecting Both Testes and CNS but Not Reported Concurrently |

|---|---|

| Bacteria | |

| Brucella species [16] | Treponema pallidum |

| Escherichia coli (postprocedure) [17] | |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosisa [18, 19] | |

| Nocardia species [20] | |

| Viruses | |

| Enterovirus | Dengue virus |

| Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus [21] | Epstein-Barr virus |

| Mumps virus [22] | Herpes simplex virus |

| West Nile virus [23] | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| Zika virus | |

| Other | |

| Toxoplasma gondii [24] | Aspergillus species |

| Cryptococcus species | |

| Schistosoma species | |

aEpididymitis and orchitis typically present.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results underscore the utility of metagenomic sequencing in identifying pathogens in CSF, an approach that has been used previously to identify viruses in CSF based on identification of viral reads and subgenomic contigs [10, 11]. Metagenomic sequencing has also been used to sequence viral genomes from brain tissue [12, 13], sometimes requiring the use of additional methods such as PCR amplification to obtain full genomes [14, 15]. Our results extend these methods by demonstrating the first assembly of a viral genome from CSF using metagenomic sequencing. Therefore, metagenomic sequencing offers the opportunity to aid not only in diagnosis but also in molecular epidemiology of viruses causing central nervous system infection. Finally, this case illustrates the importance of maintaining a broad differential diagnosis in the setting of a known viral outbreak, including uncommon presentations of common infections.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Daniel Park and Simon Ye for guidance with computational analyses.

Financial support. This work was funded by a Broadnext10 gift from the Broad Institute. A. P. was supported by Massachusetts General Hospital (training grants T32 AI007061 and KL2 TR001100). S. S. M. was supported by Harvard Medical School (T32 AG000222).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Gire SK, Goba A, Andersen KG et al. . Genomic surveillance elucidates Ebola virus origin and transmission during the 2014 outbreak. Science 2014; 345:1369–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Matranga CB, Andersen KG, Winnicki S et al. . Enhanced methods for unbiased deep sequencing of Lassa and Ebola RNA viruses from clinical and biological samples. Genome Biol 2014; 15:519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oberste MS, Maher K, Pallansch MA. Evidence for frequent recombination within species human enterovirus B based on complete genomic sequences of all thirty-seven serotypes. J Virol 2004; 78:855–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Welliver RC, Cherry JD. Aseptic meningitis and orchitis associated with echovirus 6 infection. J Pediatr 1978; 92:239–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Willems WR, Hornig C, Bauer H, Klingmüller V. A case of Coxsackie A9 virus infection with orchitis. J Med Virol 1978; 3:137–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zadeh N, Bernstein JA, Stiasny D et al. . Index of suspicion. Pediatr Rev 2003; 24:137–42.12671100 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Palacios G, Casas I, Cisterna D et al. . Molecular epidemiology of echovirus 30: temporal circulation and prevalence of single lineages. J Virol 2002; 76:4940–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nougairede A, Bessaud M, Thiberville SD et al. . Widespread circulation of a new echovirus 30 variant causing aseptic meningitis and non-specific viral illness, South-East France, 2013. J Clin Virol 2014; 61:118–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yarmolskaya MS, Shumilina EY, Ivanova OE et al. . Molecular epidemiology of echoviruses 11 and 30 in Russia: different properties of genotypes within an enterovirus serotype. Infect Genet Evol 2015; 30:244–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hoffmann B, Tappe D, Höper D et al. . A variegated squirrel bornavirus associated with fatal human encephalitis. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:154–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wilson MR, Zimmermann LL, Crawford ED et al. . Acute West Nile virus meningoencephalitis diagnosed via metagenomic deep sequencing of cerebrospinal fluid in a renal transplant patient. Am J Transplant 2017; 17:803–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Salzberg SL, Breitwieser FP, Kumar A et al. . Next-generation sequencing in neuropathologic diagnosis of infections of the nervous system. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2016; 3:e251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morfopoulou S, Brown JR, Davies EG et al. . Human coronavirus OC43 associated with fatal encephalitis. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:497–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Naccache SN, Peggs KS, Mattes FM et al. . Diagnosis of neuroinvasive astrovirus infection in an immunocompromised adult with encephalitis by unbiased next-generation sequencing. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60:919–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Frémond ML, Pérot P, Muth E et al. . Next-generation sequencing for diagnosis and tailored therapy: a case report of astrovirus-associated progressive encephalitis. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2015; 4:e53–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kanık-Yüksek S, Gülhan B, Ozkaya-Parlakay A, Tezer H. A case of childhood brucellosis with neurological involvement and epididymo-orchitis. J Infect Dev Ctries 2014; 8:1636–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Assimacopoulos A, Johnston B, Clabots C, Johnson JR. Post-prostate biopsy infection with Escherichia coli ST131 leading to epididymo-orchitis and meningitis caused by Gram-negative bacilli. J Clin Microbiol 2012; 50:4157–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Joosten AA, van der Valk PD, Geelen JA et al. . Tuberculous meningitis: pitfalls in diagnosis. Acta Neurol Scand 2000; 102:388–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cogan SR, Bornstein JS. Tuberculoma of the brain with tuberculous adenitis and epididymitis. Ann Intern Med 1959; 50:796–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dehghani M, Dehghani SM, Davarpanah MA. Epididymo-orchitis and central nervous system nocardiosis in a bone marrow transplant recipient for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Exp Clin Transplant 2009; 7:264–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lewis JM, Utz JP. Orchitis, parotitis and meningoencephalitis due to lymphocytic-choriomeningitis virus. N Engl J Med 1961; 265:776–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hviid A, Rubin S, Mühlemann K. Mumps. Lancet 2008; 371:932–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smith RD, Konoplev S, DeCourten-Myers G, Brown T. West Nile virus encephalitis with myositis and orchitis. Hum Pathol 2004; 35:254–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haskell L, Fusco MJ, Ares L, Sublay B. Disseminated toxoplasmosis presenting as symptomatic orchitis and nephrotic syndrome. Am J Med Sci 1989; 298:185–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.