Abstract

Background/Aims

Variation exists among anesthesia providers as to acceptable timing of NPO (“nothing by mouth”) for elective colonoscopy procedures. There is a need to balance optimal colonic preparation, patient convenience, and scheduling efficiency with anesthesia safety concerns. We reviewed the evidence for the relationship between NPO timing and aspiration incidence and colonoscopy rescheduling.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE (1990–April 2015) for English language studies of any design and included them if at least one bowel preparation regimen was completed within 8 hours of colonoscopy. Study characteristics, patient characteristics, and outcomes were abstracted and verified by investigators. We determined risk of bias for each study and overall strength of evidence for primary and secondary outcomes.

Results

We included 28 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 2 controlled clinical trials, and 10 observational reports. Six studies reported on aspiration; none found that shorter NPO status prior to colonoscopy increased aspiration risk, though studies were not designed to assess this outcome (low strength of evidence). One RCT found fewer rescheduled procedures following split-dose preparation but NPO status was not well-documented (insufficient evidence).

Conclusions

Aspiration incidence requiring hospitalization during colonoscopy with moderate or deep sedation is very low. No study found that shorter NPO status prior to colonoscopy increased aspiration risk. We did not find direct evidence of the effect of NPO status on colonoscopy rescheduling.

1. Introduction

Fourteen million colonoscopies are performed annually in the United States for screening, diagnosis, surveillance, and treatment of numerous colonic conditions. To optimize colon lining visualization, patients are advised to split the bowel preparation regimen such that half of the dose is taken in the evening prior to colonoscopy and the other half is taken ideally within 2–6 hours of the planned procedure [1–4]. In addition, some level of sedation (typically moderate or deep) is used in almost all colonoscopies to facilitate patient comfort and procedure quality [5, 6].

For both moderate and deep sedations, there is significant variation among anesthesia providers as to the acceptable timing of NPO (“nothing by mouth”) including how many hours prior to the planned procedure can the last bowel preparation dose be taken in order to minimize anesthesia risk (primarily aspiration). Practice guidelines from the American Society of Anesthesiologists Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters for preoperative fasting for healthy patients undergoing elective procedures suggest the following minimum fasting periods with the goal of minimizing anesthesia-related risks (primarily aspiration): 2 hours for clear liquids (e.g., water, fruit juice without pulp, carbonated beverages, clear tea, and black coffee), 6 hours for nonhuman milk, and 6 hours for a light meal (i.e., toast and clear liquids) [7]. The guideline authors note that the published clinical evidence is insufficient to clearly define a relationship between NPO status and risk of emesis/reflux or pulmonary aspiration. Furthermore, it is unclear how different bowel preparation agents would be classified (clear liquids or not), how the potential toxicity of bowel preparation agents might impact anesthesia-related risks, and how the volume of bowel preparation agent consumed might differ from the volume of liquids considered acceptable in the guidelines.

Several systematic reviews have reported the association of shorter time between preparation intakes with better quality of bowel preparation [1, 8, 9]. Based on these studies, recent gastrointestinal (GI) multisociety guidelines have recommended the use of split-dose bowel preparation for colonoscopy [4]. There is a need to balance optimal colonic preparation, patient convenience, and scheduling efficiency with safety concerns for an elective procedure. We reviewed the evidence on the relationship between timing of NPO and the incidence of aspiration and other anesthesia-related harms during elective colonoscopy.

2. Methods

This report is based on research conducted by the Evidence-based Synthesis Program (ESP) site at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center, Minneapolis, MN, funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI).

Our primary outcomes were aspiration and rescheduled colonoscopies. Secondary outcomes of interest included diagnostic yield, completion rate, and adenoma detection rate. Other secondary and intermediate outcomes evaluated are discussed in our full report [10].

2.1. Data Source

We searched MEDLINE (OVID) for English language articles published from 1990 to April 2015. Detailed search strategy is presented in the Appendix. We also searched reference lists of guidelines, existing reviews, and included studies and received reference suggestions from stakeholders, technical expert panel members, and peer reviewers.

2.2. Study Selection

Abstracts of citations identified in the literature search were assessed for relevance, and full-text reports of studies identified as potentially eligible were obtained for an independent review by two investigators. We included studies of any design that reported outcomes following bowel preparation if at least one preparation was completed within 8 hours of the colonoscopy procedure. Only studies of adults, undergoing colonoscopy with moderate or deep sedation, in inpatient or outpatient settings, and reporting outcomes during colonoscopy or recovery from colonoscopy were included. We also identified population-based studies reporting aspiration during colonoscopy.

2.3. Data Extraction and Risk of Bias Assessment

Study characteristics (inclusion/exclusion criteria and preparation interventions or NPO status), patient characteristics, and outcomes were abstracted onto tables and verified by investigators. We also extracted information about timing of liquids other than bowel preparation agents allowed prior to colonoscopy from the 11 studies that reported that information.

Risk of bias (low, moderate, or high) was determined for each included study using a modification of the Cochrane approach [11]. Low risk of bias randomized controlled trials (RCTs) had adequate allocation sequence generation and allocation concealment, blinding, and few patients with incomplete data. Low risk of bias observational studies was prospective, enrolled consecutive patients, used appropriate methods for handling missing data (or no missing data), and characteristics of the NPO groups were similar.

We rated the overall strength of the body of evidence for our primary and secondary outcomes using the method reported by Owens et al. [12].

3. Results

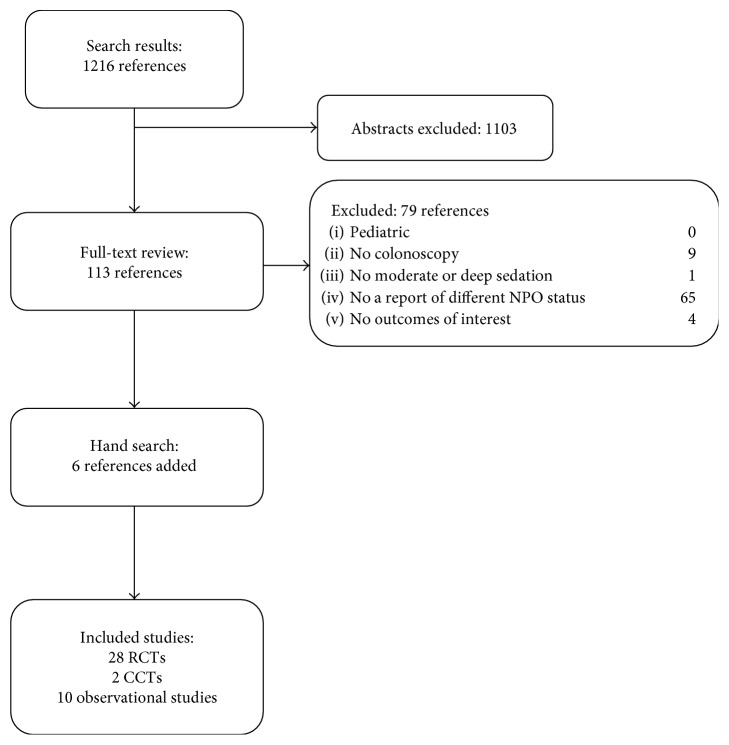

Our literature search yielded 1216 abstracts or titles of which 40 were included (28 RCTs, 2 CCTs, and 10 observational studies), with a total of 22,936 patients [13–53]. The literature flow chart is seen in Figure 1. A summary of baseline characteristics for the 28 RCTs, 2 CCTs, and 10 observational studies is presented in Table 1. Detailed study characteristics and risk of bias criteria for all included studies are presented in the full evidence report [10].

Figure 1.

Literature flow chart.

Table 1.

Summary of baseline characteristics.

| Characteristic | Mean (range) Unless otherwise noted |

Number of studies reported |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients evaluated | 22,936 (80 to 5175) | 40 |

| Randomized controlled trials, number of patients | 9304 (80 to 895) | 28 |

| Controlled clinical trials, number of patients | 740 (328 to 412) | 2 |

| Observational studies, number of patients | 12,892 (100 to 5175) | 10 |

| Age of subjects, years (range of means) | 57 (44 to 63) | 34 |

| Age of subjects, years (range of medians) | 55 to 65 | 3 |

| Gender, male, % | 46 (28 to 81) | 38 |

| Indication for colonoscopy screening, % | 61 (0a to 100) | 20 |

| Location—USA/Canada, number of patients | 12,208 (100 to 5175) | 17 |

| Location—Asia/Australia, number of patients | 8045 (80 to 3079) | 14 |

| Location—Europe, number of patients | 2683 (160 to 895) | 9 |

aTwo studies reported that screening was not an indication for colonoscopy. Chiu et al. [20] included participants who had colorectal neoplasms detected at a screening colonoscopy and were scheduled for a second colonoscopic examination for either elective polypectomy or endoscopic mucosectomy. Manno et al. [41] included participants with a positive fecal occult test or those in surveillance postpolypectomy.

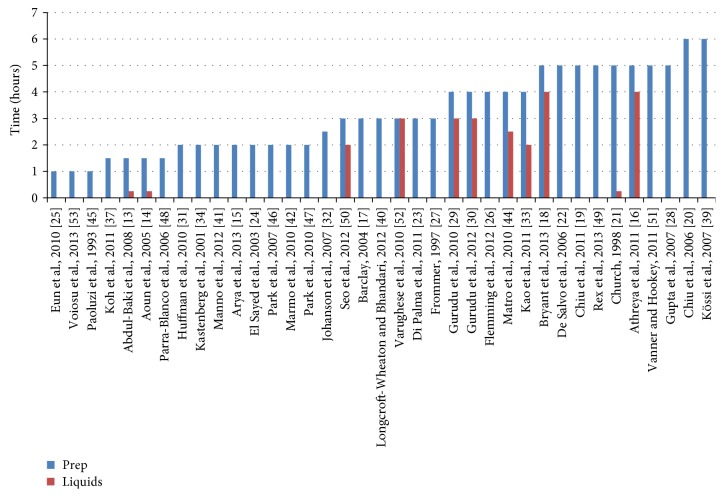

Figure 2 displays minimum NPO times based on bowel preparation time and on time before the procedure that clear liquids were allowed. The majority of studies included an NPO time of 4 hours or less. The most frequently reported outcome (39 of the 40 included studies) was an intermediate outcome, quality of bowel preparation. Detailed findings for quality of bowel preparation are presented in the full evidence report [10]. We focus here on the 19 studies reporting our primary and secondary outcomes.

Figure 2.

Minimum time from the end of bowel preparation to procedure (blue lines) or time before procedure when liquids were stopped (red lines). Three studies did not provide sufficient information to determine a minimum time from the end of preparation to procedure (Khan et al., 2010 [36], Kolts et al., 1993 [38], and Mathus-Vliegen and van der Vliet, 2013 [43]). Studies where patients were allowed liquids until time of procedure are indicated by a time of 0.25 hours. Citations are “author, year (reference number).”

3.1. Incidence of Aspiration

Six studies (4 RCTs and 2 observational studies) reported on aspiration (Table 2). Sample sizes ranged from 115 to 1345 [29, 31, 41, 43, 44, 52]. In 5 of the studies, no aspirations occurred during colonoscopy [29, 31] or during colonoscopy or within the 30 days postcolonoscopy [43] or authors reported “no complications related to sedation” [41, 52]. In 4 of the studies, bowel preparation was completed at least 2 to 4 hours prior to colonoscopy; the fifth study used a split-dose regimen but did not report when the final dose was consumed with respect to colonoscopy time. In 2 studies, patients were allowed clear liquids up to 3 hours before the procedure.

Table 2.

Summary of studies assessing aspiration events in relation to NPO status.

| Author, year [reference number] Study design, sample size NPO status groups (1 = intervention; 2 = control) |

Aspiration | |

|---|---|---|

| NPO group 1 | NPO group 2 | |

| Gurudu et al., 2010 [29] | No episodes of bronchoaspiration were recorded, including in the procedures performed in patients taking same-day bowel preparation | |

| Observational: n = 1,345 | ||

| NPO status 1: ≥4 hours | ||

| NPO status 2: >8 hours | ||

|

| ||

| Huffman et al., 2010 [31] | None of the patients in any group had clinical evidence of aspiration during their procedures | |

| Observational: n = 301 | ||

| NPO status 1: ≥2 hours | ||

| NPO status 2: >8 hours | ||

|

| ||

| Manno et al., 2012 [41] | No major complications related to sedation | |

| RCT: n = 336 | ||

| NPO status 1: 2 hours | ||

| NPO status 2: >8 hours | ||

|

| ||

| Mathus-Vliegen and van der Vliet, 2013 [43] | No events during 30-day period (from charts of patients and a complication database) | |

| RCT: n = 188 analyzed | ||

| NPO status 1: hours unclear (split-dose exam (p.m.)) | ||

| NPO status 2: >8 hours | ||

|

| ||

| Matro et al. 2010 [44] | 1.6% (1/61) were aspirated during the procedure | 0/54 |

| RCT, n = 115 analyzed | ||

| NPO status 1: 4 hours (a.m. prep only) | ||

| NPO status 2: 4 hours (p.m./a.m. prep) | ||

|

| ||

| Varughese et al., 2010 [52] | No sedation complications | |

| RCT: n = 136 | ||

| NPO status 1: ≥3 hours | ||

| NPO status 2: >8 hours | ||

NPO: nil per os; RCT: randomized controlled trial.

One small RCT (outcome data for 115 of 125 patients randomized) reported one aspiration event requiring hospitalization during colonoscopy under moderate sedation [44]. The patient was described as severely obese (BMI = 40 kg/m2) but with no other obvious risk factors for aspiration. The patient was assigned to consume one liter of bowel preparation agent seven hours before colonoscopy and an additional one liter 4 hours before. Patients in this trial were allowed clear liquids until 2.5 hours before the procedure. We found low-strength evidence that shorter duration of NPO is not associated with a higher incidence rate of aspiration.

3.2. Additional Studies of Aspiration during Colonoscopy

Several hospital- or population-based studies reported on aspiration during colonoscopy. However, none documented duration of NPO status prior to the colonoscopy. In a large database study, the incidence of aspiration requiring hospitalization during 165,527 outpatient diagnostic colonoscopies in 100,359 Medicare patients age 66 years and older (mean age = 76 years) was 0.14% for patients having colonoscopy under deep sedation requiring anesthesia assistance (as identified by a CPT-4 code) and 0.10% for patients under moderate sedation without anesthesia assistance [54]. A study of 23,508 outpatient colonoscopies at 3 hospitals in Australia reported one case (0.004%) of aspiration requiring hospitalization in a patient undergoing colonoscopy with general anesthesia [55]. A study of 3155 colonoscopies performed with sedation managed by an anesthesiologist in adults at a single hospital in Italy reported that 0.16% of patients undergoing colonoscopy had an aspiration requiring “some intervention by an anesthesiologist” [56]. Aspirations requiring hospitalizations were not reported. Patients were instructed to fast according to guidelines in place at the time—clear liquids up to 2 hours before the procedure and a light meal (toast and clear liquid) up to 6 hours before the procedure.

3.3. Rescheduled Colonoscopies

One moderate risk of bias RCT (n = 113) reported rescheduled colonoscopies [38]. The percentage of rescheduled colonoscopies was significantly lower (P = 0.01) in the group that completed bowel preparation in the morning of the procedure (3%), taking a split-dose of a sodium phosphate regimen, than in groups consuming a polyethylene glycol solution (8%) or a castor oil solution (24%) in the evening before the procedure. Differences in the bowel preparation solutions between groups and imprecise reporting of timing of completion of bowel preparation limit our ability to draw firm conclusions about the role of NPO status on rescheduling. Strength of evidence was insufficient.

4. Discussion

We found low-strength evidence that risk of aspiration is not related to duration of NPO status prior to colonoscopy. However, few studies reported duration of NPO and aspiration or other risks related to colonoscopy. Studies were limited in size and were not population-based, limiting generalizability.

In hospital- and population-based studies, aspiration incidence requiring hospitalization during colonoscopy with moderate or deep sedation is very low (1 in 1000 or less) and on the order of magnitude commonly accepted for adverse effects of similar clinical importance due to other elective procedures. The largest study, and the only one conducted in the US, reported on patients age 66 and older (mean age 75 years). The applicability of results to younger individuals is uncertain though the reported percentage may overestimate aspiration risk. NPO status was not reported and the participants in these studies likely had wide ranges of timing from NPO to colonoscopy; many were likely longer than 2 to 4 hours. It is also important to acknowledge that in the US, there are no systematic tracking methods to track complications from colonoscopy—especially related to NPO status, and there is the possibility of under- or misreporting.

Many of the studies eligible for our review excluded patients with serious comorbidities. Few studies recorded mean or range of NPO status timing (including time of last ingestion of water, clear liquids, or bowel preparation substance). Furthermore, only 26 of 40 included studies reported on use of sedation during colonoscopy. Populations enrolled in eligible studies were broadly applicable to many individuals undergoing elective colonoscopy in the United States. Eligible studies typically included patients 45 to 65 years, and approximately 50% of patients were enrolled in studies done in the US. Nearly one-half of patients were male and two-thirds of colonoscopies were performed for cancer screening.

Other studies have focused on bowel preparation quality as their main outcome of interest and reported that shorter time from completion of colonic preparation to colonoscopy is associated with greater bowel preparation quality compared to longer time intervals. A recent systematic review assessed the efficacy of split- versus nonsplit-dose bowel preparation for quality of cleansing [9]. The authors included 29 studies and reported that an adequate preparation was obtained in 85% of patients in the split-dose group, compared to 63% in the nonsplit-dose group. Based on these studies, recent guidelines by the US multisociety task force on colorectal cancer [4] emphasized the importance of optimal bowel cleansing for a high-quality exam and recommended the use of split-dose bowel preparations, with the second half of the purgative given 4–6 hours before the time of colonoscopy. In addition, recent guidelines on quality benchmarks [57] have recommended that quality of bowel preparation should be monitored for colonoscopy and adequate bowel preparation should be achieved in ≥85% of colonoscopies. These reports make it essential for a colonoscopy program to monitor and maximize high quality of bowel preparation and balance the benefits of shorter NPO with any potential harms from risk of aspiration or other anesthesia-related complications.

Our findings indicate important knowledge gaps including the following: (1) an accurate assessment of aspiration requiring hospitalization and other serious anesthesia-related adverse events according to NPO status, (2) the extent of and reasons for variation in anesthesia NPO status practice and policy, (3) the effect of NPO status on procedure rescheduling and patient adherence and satisfaction, and (4) reasons for reduced patient adherence to recommendations for NPO status and bowel preparation. Future studies to close these knowledge gaps could improve care quality.

Specifically, to systematically assess duration of NPO status in relation to timing of colonoscopy and to record aspiration and other serious adverse events using standardized diagnostic criteria, prospective registries could be established. Providers would record timing of preparation, duration of NPO, and sedation procedures and then track adverse events over the next 48 to 72 hours. Future efforts could be directed towards developing standard methods to collate this information and initiate analyses to assess the association of duration of NPO and colonoscopy outcome. Special populations at higher risk of aspiration and other anesthesia-related outcomes would be of particular interest, such as elderly patients, patients with high comorbidities, and those with disabilities that limit ability to follow and complete the bowel preparation instructions. There is also a need to evaluate the effect of variable durations of NPO status prior to colonoscopy on patient satisfaction, adherence to colonoscopy, and endoscopy scheduling processes, including delays in timely receipt of colonoscopy. A better understanding of why some patients do not adhere to NPO status recommendations and methods to improve communication and adherence is needed. Alternative scheduling methods, including later but same-day colonoscopy, could also be evaluated to reduce “cancellations” due to NPO nonadherence.

Finally, evidence-based multisociety consensus guidelines that bring together patient representatives and members from anesthesia, gastroenterology, and general medicine are needed. Recommendations for NPO status also affect other gastroenterology procedures as well as procedures performed by other specialties (e.g., pulmonary and cardiology). Therefore, including representatives across a wide range of disciplines and procedures would be helpful in developing evidence-based recommendations targeted to specific procedures and likely benefits and harms. Important items in guideline development include determining the “clinically important” balance between critical outcomes to anesthesiologists, gastroenterologists (and other specialty groups performing procedures), and patients including aspiration rates due to NPO status, colonoscopy quality measures, resource use, and patient satisfaction and adherence.

In summary, aspiration incidence requiring hospitalization during colonoscopy with moderate or deep sedation is very low and on the order of magnitude commonly accepted for adverse effects of similar clinical importance due to other elective procedures. Participants in hospital- and population-based studies likely had wide ranges of timing from NPO to colonoscopy, and many were likely longer than 2 to 4 hours. No study documenting NPO status found that shorter NPO status prior to colonoscopy increased aspiration risk. We did not find direct evidence of the effect of NPO status on colonoscopy rescheduling.

Acknowledgments

This study is based on research conducted by the Evidence-based Synthesis Program (ESP) site located at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center, Minneapolis, MN, funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Quality Enhancement Research Initiative. Additional support is provided through the Minneapolis VA High Value Care Initiative.

Appendix

Search Strategy

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R)

colonoscopy/

colonic.ti,ab.

(endoscop$ and (colon$ or rect$)).ti,ab.

or/1–3

cathartics/ or polyethylene glycols/ or phosphates/ or laxatives/ or senna extract/ or bisacodyl/ or cascara/ or enema/ or administration, oral/

(prepara$ or enema$ or cathart$ or (polyethylene adj glycol$) or phosphat$ or laxativ$ or (senna adj extract$) or bisacodyl or cascara or PEG or miralax or golytely or nulytely or halflytely or fleet or dulcolax or pico selax or bowel prep$ or bowel purgative or oral or liquid).mp.

5 or 6

respiratory aspiration of gastric contents/ or respiratory aspiration/ or pneumonia, aspiration/ or dyspnea/ or vomiting/

(emesis or vomit$ or reflux or bronchoaspirat$ or aspirat$ or quality or detection).ti,ab.

8 or 9

4 and 7 and 10

limit 11 to yr=“1990 -Current”

limit 12 to English language

limit 13 to humans

limit 14 to (“all infant (birth to 23 months)” or “all child (0 to 18 years)” or “newborn infant (birth to 1 month)” or “infant (1 to 23 months)” or “preschool child (2 to 5 years)” or “child (6 to 12 years)” or “adolescent (13 to 18 years)”)

limit 14 to (“all adult (19 plus years)” or “young adult (19 to 24 years)” or “adult (19 to 44 years)” or “young adult and adult (19–24 and 19–44)” or “middle age (45 to 64 years)” or “middle aged (45 plus years)” or “all aged (65 and over)” or “aged (80 and over)”)

14 not 15

16 or 17

Disclosure

The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the authors who are responsible for its contents; the findings and conclusions do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Conflicts of Interest

None was declared for any authors.

Authors' Contributions

Aasma Shaukat is responsible for the study design, search strategy, data collection, analysis, writing the manuscript, and revisions. Ashish Malhotra, Nancy Greer, Roderick MacDonald, and Joseph Wels are responsible for the data collection, analysis, and revisions to the manuscript. Timothy J. Wilt is responsible for the study design data analysis and revisions to the manuscript.

References

- 1.Kilgore T. W., Abdinoor A. A., Szarzy N. M., et al. Bowel preparation with split-dose polyethylene glycol before colonoscopy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2011;73:1240–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hassan C., Bretthauer M., Kaminski M. F., et al. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2013;45:142–150. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1326186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathus-Vliegen E., Pellisé M., Heresbach D., et al. Consensus guidelines for the use of bowel preparation prior to colonic diagnostic procedures: colonoscopy and small bowel video capsule endoscopy. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2013;29:931–945. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2013.803055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson D. A., Barkun A. N., Cohen L. B., et al. Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: recommendations from the U.S. multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2014;80:543–562. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen L. B., Wecsler J. S., Gaetano J. N., et al. Endoscopic sedation in the United States: results from a nationwide survey. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006;101:967–974. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Standards of Practice Committee of the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, Lichtenstein D. R., Jagannath S., et al. Sedation and anesthesia in GI endoscopy. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2008;68:815–826. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Society of Anesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for pre-operative fasting and the use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration: application to healthy patients undergoing elective procedures. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:495–511. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181fcbfd9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martel M., Barkun A. N., Menard C., Restellini S., Kherad O., Vanasse A. Split-dose preparations are superior to day-before bowel cleansing regimens: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:79–88. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bucci C., Rotondano G., Hassan C., et al. Optimal bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: split the dose! A series of meta-analyses of controlled studies. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2014;80:566–576. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.05.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaukat A., Wels J., Malhotra A., et al. Colonoscopy outcomes by duration of NPO status prior to colonoscopy with moderate or deep sedation. VA ESP project #09-009. September 2015, http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.JPT H., Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration 2011, http://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/

- 12.Owens D. K., Lohr K. N., Atkins D., et al. AHRQ series paper 5: grading the strength of a body of evidence when comparing medical interventions—Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Effective Health-Care Program. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2010;63:513–523. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdul-Baki H., Hashash J. G., Elhajj I. I., et al. A randomized, controlled, double-blind trial of the adjunct use of tegaserod in whole-dose or split-dose polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution for colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2008;68:294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aoun E., Abdul-Baki H., Azar C., et al. A randomized single-blind trial of split-dose PEG-electrolyte solution without dietary restriction compared with whole dose PEG-electrolyte solution with dietary restriction for colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2005;62:213–218. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(05)00371-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arya V., Gupta K. A., Valluri A., Arya S. V., Lesser M. L. Rapid colonoscopy preparation using bolus lukewarm saline combined with sequential posture changes: a randomized controlled trial. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2013;58:2156–2166. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2598-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Athreya P. J., Owen G. N., Wong S. W., Douglas P. R., Newstead G. L. Achieving quality in colonoscopy: bowel preparation timing and colon cleanliness. ANZ Journal of Surgery. 2011;81:261–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barclay R. L. Safety, efficacy, and patient tolerance of a three-dose regimen of orally administered aqueous sodium phosphate for colonic cleansing before colonoscopy. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2004;60:527–533. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(04)01857-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bryant R. V., Schoeman S. N., Schoeman M. N. Shorter preparation to procedure interval for colonoscopy improves quality of bowel cleansing. Internal Medicine Journal. 2013;43:162–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2012.02963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiu H. M., Lin J. T., Lee Y. C., et al. Different bowel preparation schedule leads to different diagnostic yield of proximal and nonpolypoid colorectal neoplasm at screening colonoscopy in average-risk population. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2011;54:1570–1577. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318231d667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiu H. M., Lin J. T., Wang H. P., Lee Y. C., Wu M. S. The impact of colon preparation timing on colonoscopic detection of colorectal neoplasms—a prospective endoscopist-blinded randomized trial. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006;101:2719–2725. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Church J. M. Effectiveness of polyethylene glycol antegrade gut lavage bowel preparation for colonoscopy—timing is the key! Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 1998;41:1223–1225. doi: 10.1007/BF02258217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Salvo L., Borgonovo G., Ansaldo G. L., et al. The bowel cleansing for colonoscopy. A randomized trial comparing three methods. Annali Italiani di Chirurgia. 2006;77:143–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Palma J. A., Rodriguez R., McGowan J., Cleveland M. A randomized clinical study evaluating the safety and efficacy of a new, reduced-volume, oral sulfate colon-cleansing preparation for colonoscopy. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2009;104:2275–2284. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El Sayed A. M., Kanafani Z. A., Mourad F. H., et al. A randomized single-blind trial of whole versus split-dose polyethylene glycol-electrolyte solution for colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2003;58:36–40. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eun C. S., Han D. S., Hyun Y. S., et al. The timing of bowel preparation is more important than the timing of colonoscopy in determining the quality of bowel cleansing. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2011;56:539–544. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1457-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flemming J. A., Vanner S. J., Hookey L. C. Split-dose picosulfate, magnesium oxide, and citric acid solution markedly enhances colon cleansing before colonoscopy: a randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2012;75:537–544. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frommer D. Cleansing ability and tolerance of three bowel preparations for colonoscopy. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 1997;40:100–104. doi: 10.1007/BF02055690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta T., Mandot A., Desai D., Abraham P., Joshi A., Shah S. Comparison of two schedules (previous evening versus same morning) of bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2007;39:706–709. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gurudu S. R., Ratuapli S., Heigh R., DiBaise J., Leighton J., Crowell M. Quality of bowel cleansing for afternoon colonoscopy is influenced by time of administration. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;105:2318–2322. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gurudu S. R., Ramirez F. C., Harrison M. E., Leighton J. A., Crowell M. D. Increased adenoma detection rate with system-wide implementation of a split-dose preparation for colonoscopy. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2012;76:603–608. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.04.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huffman M., Unger R. Z., Thatikonda C., Amstutz S., Rex D. K. Split-dose bowel preparation for colonoscopy and residual gastric fluid volume: an observational study. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2010;72:516–522. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.03.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johanson J. F., Popp J. W., Jr., Cohen L. B., et al. A randomized, multicenter study comparing the safety and efficacy of sodium phosphate tablets with 2L polyethylene glycol solution plus bisacodyl tablets for colon cleansing. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2007;102:2238–2246. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kao D., Lalor E., Sandha G., et al. A randomized controlled trial of four precolonoscopy bowel cleansing regimens. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2011;25:657–662. doi: 10.1155/2011/486084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kastenberg D., Chasen R., Choudhary C., et al. Efficacy and safety of sodium phosphate tablets compared with PEG solution in colon cleansing: two identically designed, randomized, controlled, parallel group, multicenter phase III trials. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2001;54:705–713. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.119733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kastenberg D., Barish C., Burack H., et al. Tolerability and patient acceptance of sodium phosphate tablets compared with 4-L PEG solution in colon cleansing: combined results of 2 identically designed, randomized, controlled, parallel group, multicenter phase 3 trials. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2007;41:54–61. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000212662.66644.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khan M. A., Piotrowski Z., Brown M. D. Patient acceptance, convenience, and efficacy of single-dose versus split-dose colonoscopy bowel preparation. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2010;44:310–311. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181c2c92a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koh D. H., Lee H. L., Kwon Y. I., et al. The effect of eating lunch before and afternoon colonoscopy. Hepato-Gastroenterology. 2011;58:775–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kolts B. E., Lyles W. E., Achem A. R., Burton L., Geller A. J., MacMath T. A comparison of the effectiveness and patient tolerance of oral sodium phosphate, castor oil, and standard electrolyte lavage for colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy preparation. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 1993;88:1218–1223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kössi J., Krekelä I., Patrikainen H., Vuorinen T., Luostarinen M., Laato M. The cleansing result of oral sodium phosphate is inversely correlated with time between the last administration and colonoscopy. Techniques in Coloproctology. 2007;11:51–54. doi: 10.1007/s10151-007-0325-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Longcroft-Wheaton G., Bhandari P. Same-day bowel cleansing regimen is superior to a split-dose regimen over 2 days for afternoon colonoscopy: results from a large prospective series. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2012;46:57–61. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318233a986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manno M., Pigo F., Manta R., et al. Bowel preparation with polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution: optimizing the splitting regimen. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2012;44:576–579. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marmo R., Rotondano G., Riccio G., et al. Effective bowel cleansing before colonoscopy: a randomized study of split-dosage versus non-split dosage regimens of high-volume versus low-volume polyethylene glycol solutions. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2010;72:313–320. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mathus-Vliegen E. M. H., van der Vliet K. Safety, patient’s tolerance, and efficacy of a 2-liter vitamin C-enriched macrogol bowel preparation: a randomized, endoscopist-blinded prospective comparison with a 4-liter macrogol solution. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2013;56:1002–1012. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182989f05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matro R., Shnitser A., Spodik M., et al. Efficacy of morning-only compared with split-dose polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution for afternoon colonoscopy: a randomized controlled single-blind study. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;105:1954–1961. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paoluzi O. A., Di Paolo M. C., Ricci F., et al. A randomized controlled trial of a new PEG-electrolyte solution compared with a standard preparation for colonoscopy. The Italian Journal of Gastroenterology. 1993;25:174–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park J. S., Sohn C. I., Hwang S. J., et al. Quality and effect of single dose versus split dose of polyethylene glycol bowel preparation for early-morning colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2007;39:616–619. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park S. S., Sinn D. H., Kim Y. H., et al. Efficacy and tolerability of split-dose magnesium citrate: low-volume (2 liters) polyethylene glycol vs. single- or split-dose polyethylene glycol bowel preparation for morning colonoscopy. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;105:1319–1326. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parra-Blanco A., Nicolas-Perez D., Gimeno-Garcia A., et al. The timing of bowel preparation before colonoscopy determines the quality of cleansing, and is a significant factor contributing to the detection of flat lesions: a randomized study. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006;12:6161–6166. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i38.6161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rex D. K., Katz P. O., Bertiger G., et al. Split-dose administration of a dual-action, low-volume bowel cleanser for colonoscopy: the SEE CLEAR I study. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2013;78:132–141. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seo E. H., Kim T. O., Park M. J., et al. Optimal preparation-to-colonoscopy interval in split-dose PEG bowel preparation determines satisfactory bowel preparation quality: an observational prospective study. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2012;75:583–590. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vanner S., Hookey L. C. Timing and frequency of bowel activity in patients ingesting sodium picosulphate/magnesium citrate and adjuvant bisacodyl for colon cleansing before colonoscopy. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2011;25:663–666. doi: 10.1155/2011/950263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Varughese S., Kumar A. R., George A., Castro F. J. Morning-only one-gallon polyethylene glycol improves bowel cleansing for afternoon colonoscopies: a randomized endoscopist-blinded prospective study. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;105:2368–2374. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Voiosu T., Ratiu I., Voiosu A., et al. Time for individualized colonoscopy bowel-prep regimens? A randomized controlled trial comparing sodium picosulphate and magnesium citrate versus 4-liter split-dose polyethylene glycol. Journal of Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases. 2013;22:129–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cooper G. S., Kou T. D., Rex D. K. Complications following colonoscopy with anesthesia assistance. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2013;173:551–556. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Viiala C. H., Zimmerman M., Cullen D. J. E., Hoffman N. E. Complication rates of colonoscopy in an Australian teaching hospital environment. Internal Medicine Journal. 2003;33:355–359. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-5994.2003.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Agostoni M., Fanti L., Gemma M., Pasculli N., Beretta L., Testoni P. A. Adverse events during monitored anesthesia care for GI endoscopy: an 8-year experience. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2011;74:266–275. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rex D. K., Schoenfeld P. S., Cohen J., et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2015;81:31–53. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]