Abstract

Background

Donepezil is an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor frequently prescribed for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) though not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this indication. In Alzheimer’s disease, butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) activity increases with disease progression and may replace acetylcholinesterase function. The most frequent polymorphism of BChE is the K-variant, which is associated with lower acetylcholine-hydrolyzing activity. BChE-K polymorphism has been studied in Alzheimer’s disease progression and donepezil therapy, and has led to contradictory results.

Objectives

To determine whether BChE-K genotype predicts response to donepezil in MCI.

Methods

We examined the association between BChE-K genotype and changes in cognitive function using the data collected during the ADCS vitamin E/donepezil clinical trial in MCI.

Results

We found significant interactions between BChE-K genotype and the duration of donepezil treatment, with increased changes in MMSE and CDR-SB scores compared to the common allele in MCI subjects treated during the 3-year trial. We found faster MMSE decline and CDR-SB rise in BChE-K homozygous individuals treated with donepezil compared to the untreated. We observed similar interactions between BChE-K genotype and steeper changes in MMSE and CDR-SB scores in APOE4 carriers treated with donepezil compared to controls.

Interpretation

BChE-K polymorphisms are associated with deleterious changes in cognitive decline in MCI patients treated with donepezil for 3 years. This indicates that BChE-K genotyping should be performed to help identify subsets of subjects at risk for donepezil therapy, like those carrying APOE4. BChE-K and APOE4 carriers should not be prescribed off-label donepezil therapy for MCI management.

Keywords: donepezil, pharmacogenetics, mild cognitive impairment, butyrylcholinesterase, Alzheimer’s disease, therapeutics, clinical trial

Introduction

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a transitional state between normal age-related changes in cognition and dementia [1–3]. Most amnestic MCI patients display pathological features of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1, 4]. The incidence of AD dementia is about 10 to 15 percent per year among amnestic MCI compared to 1 to 2 percent among cognitively normal elderly [1, 2]. This indicates that approximately 80% of amnestic MCI will develop dementia within six years, for which some but not all will be due to AD.

Donepezil is currently the most commonly prescribed medication for the treatment of cognitive symptoms in MCI and AD, even though it is not approved by the Food Drug Administration for the early symptomatic stages of AD (e.g. MCI). Donepezil belongs to the acetylcholinesterase inhibitors pharmacological class. It primarily blocks the breakdown of acetylcholine by selectively inhibiting the acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzymes. Donepezil also inhibits butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) activity, but displays a much lower affinity towards BChE compared to AChE [5]. Both BChE and AChE are involved in ACh metabolism and thus are important for the cholinergic function in the brain. The majority of cholinesterase activity in healthy brain is attributed to AChE, and BChE plays only a minor role. Studies have reported that during AD progression as AChE activity declines BChE activity progressively increases, suggesting that BChE is replacing AChE function over time [6].

The most common genetic variant of BChE was named the K variant (BChE-K) in honor of Werner Kalow [7]. This variant results from a missense polymorphism in BChE gene at nucleotide 1615 (rs1803274; allelic frequencies of ~ 0.16) that changes codon 539 from GCA (Ala) to ACA (Thr) at the C terminus of BChE [7]. As a result of this single nucleotide polymorphism, BChE-K has a reduced catalytic activity, about 30% of the usual BChE [8]. The effect of BChE K-variant in AD progression has been studied over the past 20 years, and lead to contradictory results [9–14]. However, a recent meta- analysis conducted by Alzgene indicates that there is no association between the K-variant and the onset of AD (41 studies, OR 1.05; 95% confidence interval [0.92, 1.18], I2 62; http://www.alzgene.org/meta.asp?geneID=74, accessed on Aug. 18 2016).

Studies reporting the influence of BChE-K genotype on donepezil response are limited to its use in AD [11, 15, 16]. In their case-only study, Scacchi et al. did not find a role of the BChE-K variant on the efficacy of treatment with donepezil in late-onset AD (LOAD) patients. Another study in AD failed to detect a treatment difference in BChE-K carriers when comparing the effect of BChE genotype on the response to donepezil or rivastigmine, another AChE inhibitor [15]. More recently, Han et al. conducted a case-only study in Korean AD subjects treated with rivastigmine and concluded that the BChE-K allele was a significant predictor for a poor response [16].

To our knowledge a pharmacogenetics study examining the association between BChE-K polymorphism and donepezil response has not been reported in MCI. In the largest donepezil clinical trial conducted on MCI patients, donepezil was shown to reduce the progression to AD during the first year of therapy, but not at the end of the 3-year trial [3]. Donepezil pharmacogenetics in MCI have been limited to a secondary analysis in this trial, which showed that the efficacy of donepezil persisted at year two in MCI subjects carrying the APOE4 allele, the major genetic risk factor for AD [2, 3]. The objective of our study was to determine whether the treatment response to donepezil is modulated by BChE K-variant genotype.

Patients and methods

Patients

Men and women aged 55 to 90 with MCI, defined as a primary memory impairment with relative sparing of other cognitive functions. The criteria for inclusion were amnestic MCI of a degenerative nature, impaired memory, a Logical Memory delayed-recall score approximately 1.5 to 2 SD below an education-adjusted norm, a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) of 0.5 and a score of 24 to 30 on the Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE) [3]. Subjects on donepezil received an initial dose of 5 mg daily which was increased to 10 mg after six weeks. The control group in our analyses includes subjects from the placebo and the 2000 IU of vitamin E arms. The rationale for combining these 2 groups was the lack of observed therapeutic effect of vitamin E [3]. All study protocols were approved by each site’s institutional review board and all study participants provided written informed consent before participating in the trial and biospecimen collection.

Genotyping

All genomic DNA samples collected during the Donepezil/Vitamin E trial were extracted from blood and quantified using Picogreen (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) before being genotyped using the Illumina 610Quad array (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) at Genizon Biosciences (Montreal, Quebec, Canada). QC procedures were performed using the genetic analysis package PLINK (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/plink/). The donepezil/Vitamin E dataset included 574 subjects with BChE rs1803274 genotypes and phenotypic data at baseline; 193 were among the donepezil arm and 381 among the donepezil naïve group (i.e., placebo and vitamin E arms).

Outcome measures

Our preplanned outcome variables were the change from baseline on the MMSE and Clinical Dementia Rating - sum of boxes (CDR-SB) scores [3]. As AD progresses, MMSE scores decline while CDR-SB scores increase. The primary variables of interest were treatment, genotype, and duration of treatment in months, with their interaction used to assess the interaction between genotype and donepezil effect on cognitive function response. A secondary end point was the time to the development of possible or probable AD [3].

Statistical analysis

All available data from 6, 12, 18, 24, 30 and 36 months were used, and differences in cognitive test results (dMMSE and dCDR-SB) between baseline and follow-up treatment visits were calculated. We used linear regression models, adjusting for age, gender and APOE4, to test the influence of BChE polymorphism rs1803274 on changes in MMSE and CDR-SB scores at the end of the 3-year trial. We used PLINK software v1.07 to estimate the beta regression coefficient for rs1803274 in each group. To determine whether the association was a response to treatment, or due to a main effect of genotype on the history of disease progression, we also tested the interaction term of rs1803274 and donepezil treatment (treated vs. non-treated, i.e. vit. E and placebo arms) subjects on MMSE and CDR-SB changes. The mixed models with autoregressive plus random effects [AR(1)+RE)] covariance structure were selected to assess the interaction between treatment groups, BChE-K genotype and duration of therapy. In addition, the interactions between treatment groups and duration of therapy were also stratified by BChE-K genotypes at loci rs1803274. In order to estimate whether BChE-K polymorphism was independently associated with MMSE and CDR-SB scores changes, besides adjusting for APOE4 in the model, stratified analysis by APOE4 carriers was also performed.

The Kaplan-Meier curves were used to estimate time to progression to possible or probable AD [3] and the difference of progression time between treated and control groups was tested by Cox-proportional hazard model. A z-test (the difference in the proportions divided by the standard error of the difference) was used to compare estimated survival rates at various points on the Kaplan–Meier curves (at 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months).

Results

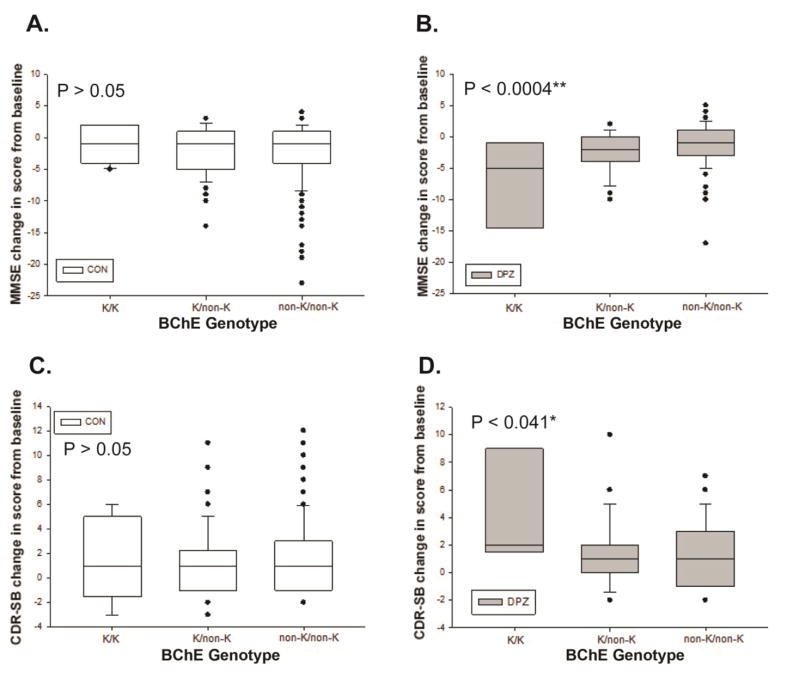

The frequency of rs1803274 K-carriers was ~ 33% in our population (31% in the controls and 35% in the treated group; P > 0.05). In the control group, no association was found between the minor allele of rs1803274 (K-variant of BChE) and MMSE decline or CDR-SB rise at 36 months [Figures 1 A and C]. However, we found that BChE K-variant is significantly associated with faster cognitive decline measured by MMSE and CDR-SB scores changes in subjects treated with donepezil for 36 months. Indeed, the K-variant, compared to the common allele, is associated with a greater decline in MMSE [−7.2 ± 3.4 (K homozygous), −2.2 ± 0.5 (K heterozygous) and −0.9 ± 0.4 (non-K); P = 0.0004] [Figure 1B] and a greater rise in CDR-SB [(4.1 ± 1.9 (K homozygous), 1.3 ± 0.4 (K heterozygous) and 1.082 ± 0.3 (non-K); P = 0.040] [Figure 1D]. When examining the entire cohort as a whole (i.e. placebo, Vitamin E and donepezil), the overall main effect of BChE-K genotype on changes of MMSE or CDR-SB scores was not significant at the end of the trial. This indicates that the association noted above was due to the response to treatment, rather than a main effect of the BChE-K genotype on the natural history of the disease progression.

Figure 1.

Effect of BChE-K genotype on cognitive decline in control (A and C) vs. donepezil treated (B and D) individuals at the end of the 36-months trial. Box plot of the mean changes of MMSE (A and B) and CDR-SB (C and D) by genotype and by treatment groups. A significant association is found between BChE K–genotype and response to donepezil (B and D).

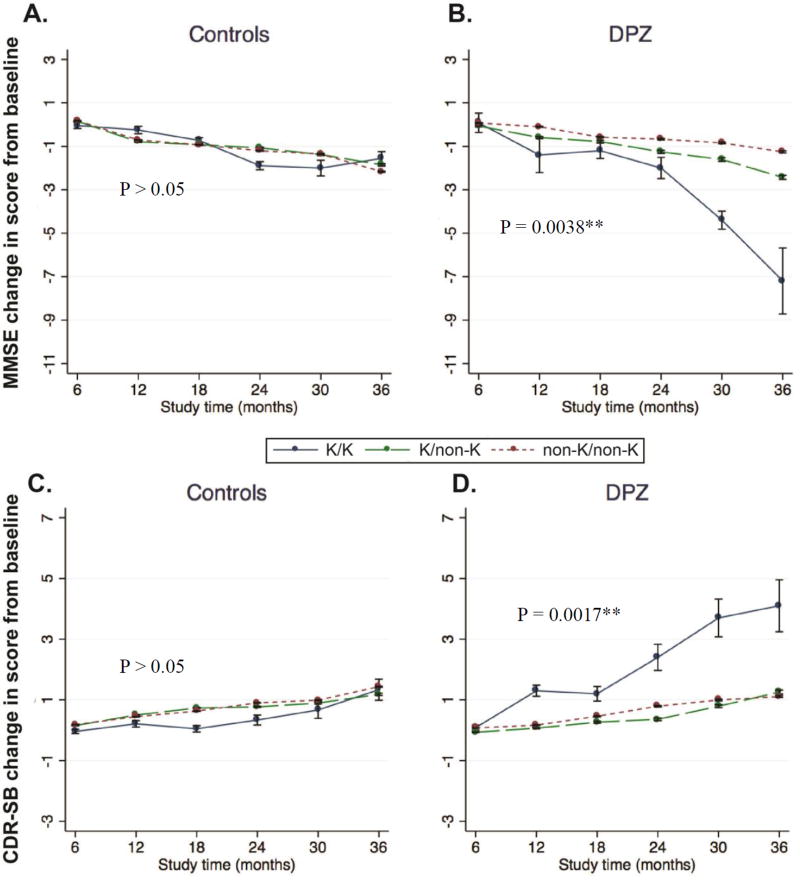

Examining the data further, we also found a highly significant interaction between treatment duration and BChE-K genotype on MMSE decline in the treated group (P < 0.0038) [Figures 2A and B]. A similar interaction between duration of therapy and increased CDR-SB was observed (P < 0.0017) [Figure 2C and D]. Our findings thus indicate a faster decline in MMSE and rise in CDR-SB scores in BChE-K homozygous subjects when treated with donepezil compared to placebo (P = 0.0096 and P = 0.008 for dMMSE abd dCDR-SB respectively) [Figure 2A and B]. However, there was no difference of progression rate between the treated and control groups at the follow-up after 36 months (P > 0.05, data not shown).

Figure 2.

Mean changes in MMSE (A and B) and CDR-SB (C and D) scores over time by BChE-K genotype and by treatment groups. BChE polymorphisms rs1803274 define sub-populations with different response to donepezil therapy in MCI subjects. The long-term treatment effects for both MMSE and CDR-SB changes are significantly different among BChE genotype groups (B and D). No significant interaction between BChE genotype and cognitive decline in treatment controls (A and C).

After stratification by BChE-K genotypes, inter-group differences in dMMSE and dCDR-SB were found with longer duration of donepezil therapy in BChE-K homozygous subjects compared to untreated controls (P = 0.026 and P = 0.014 for dMMSE and dCRD-SB respectively).

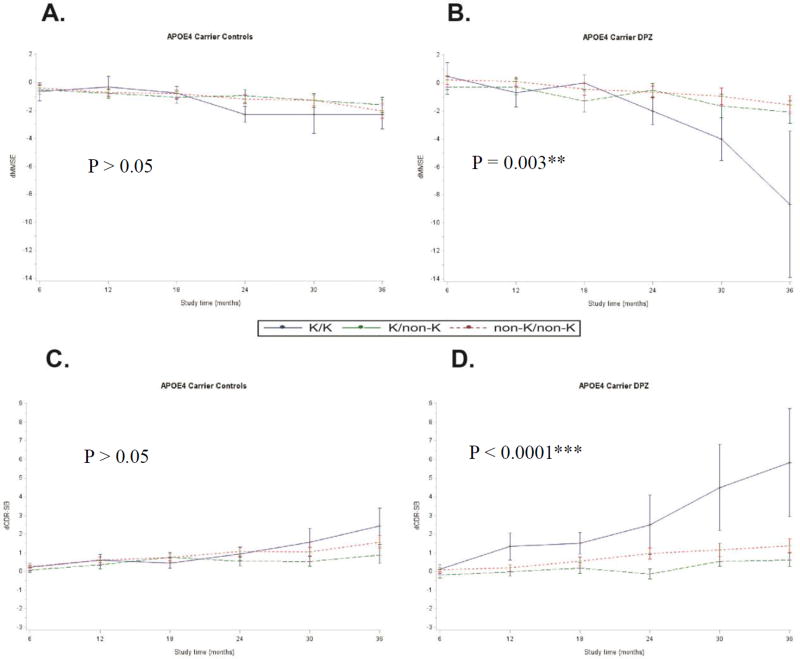

Given the fact the APOE 4 allele is the highest risk factor for late AD onset, we stratified the results between individuals carrying it or not. In APOE4 carriers treated with donepezil, the interaction between treatment duration and BChE-K genotype on MMSE decline and CDR-SB rise remained significant (P = 0.003 and P < 0.0001 for dMMSE and dCDR-SB respectively) [Figures 3B and 3D]. Similarly, significant interactions persisted between BChE-K genotype and faster MMSE decline and CDR-SB rise (P = 0.011 and P = 0.0007 for MMSE and CDR-SB respectively) in treated APOE4 carriers compared to untreated (Figure 3). In contrast, there was no significant difference among APOE4 non-carriers (supplementary Figure S1)

Figure 3.

Mean changes in MMSE (A and B) and CDR-SB (C and D) scores over time by BChE-K genotype and by treatment groups in APOE4 carriers. The long-term effect of donepezil for both MMSE and CDR-SB changes are significantly different among BChE genotype at loci rs1803274 in APOE4 carriers (B and D). No significant interaction between BChE genotype and cognitive decline in untreated APOE4 carrier subjects (A and C).

Models with additional adjustments for baseline MMSE and CDR-SB values were performed, as well as models excluding the vitamin E arm in the control group. The results remained similar (data not shown).

Discussion

It was previously reported that donepezil was ineffective at the end of the three year ADCS trial in MCI [3]. Our secondary pharmacogenetic analysis of the same trial not only confirmed these past conclusions but also indicates that donepezil can be deleterious if given to MCI patients carrying the K- variant of BChE and particularly in APOE4 carriers. Hence, our findings lead to the recommendation for the use of genetic testing prior to initiating the off-label use of donepezil in MCI patients.

First, our data shows that BChE-K genotype does not influence cognitive decline in the absence of donepezil treatment at the end of the 3-year trial. Second, we found that BChE K-carriers exhibit differential responses to donepezil compared to non-carriers, with a negative impact of donepezil treatment on cognitive performance (i.e. d-MMSE and d-CDR-SB) in the MCI K-carriers at the end of the trial (Figure 1). Lastly, our trends test indicates that the interaction between BChE-K genotype and donepezil response on cognitive function is significantly associated with the duration of treatment (Figure 2). Additional analyses stratified by BChE-K genotypes revealed that the interaction between BChE-K polymorphism and a faster cognitive decline is significant in BChE-K homozygous carriers treated with donepezil compared to controls. The stratification by APOE4 carriers showed that the interaction between BChE-K polymorphism and donepezil therapy is significant in APOE4 carriers but not in APOE4 non-carriers.

Our data analysis also confirmed that the association between BChE-K genotype and a steeper cognitive decline is due to the response to donepezil, rather than a main effect of the BChE-K genotype on the natural history of the disease progression.

These differential responses by BChE-K genotype suggest that natural BChE inhibition caused by a missense polymorphism at loci rs1803274 is deleterious for MCI subjects who are treated with an AChE inhibitor such as donepezil. Since both AChE and BChE are involved in the hydrolysis of acetylcholine in the brain [17], we can speculate that the pharmacological inhibition of AChE by donepezil and the concomitant BChE inhibition due to the missense polymorphism rs1803274 in K-variant carriers lead to an overload of ACh [18], which in turns has a deleterious effect on cholinergic synapses and therefore on the cognitive function. For example, it was shown that the inhibition of BChE in the hippocampus of AChE deficient mice (AChE−/−) causes a three-to-fivefold increases of AChE levels, while ACh levels are not affected when AChE is fully active (e.g. in wild-type mice) [18].

While the APOE4 allele is associated with an increased risk for developing AD, the interaction between APOE4 and BChE-K is unclear in AD progression and AChEI therapeutic response [16, 19, 20]. In our study, BChE-K carriers displayed a steeper cognitive decline on MMSE and CDR-SB in donepezil-treated subjects carrying APOE4. Although, we could not determine whether the interaction was stronger in the presence of the APOE4 allele, it is possible that the presence of APOE4 further alters BChE activity among BChE-K carriers which can trigger ACh metabolism imbalance and cognitive decline [20]. Indeed, Darreh-Shori et al. showed that BChE activity is reduced in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of AD individuals carrying both the APOE4 allele and the BChE-K variant, despite a similar concentration of the BChE protein compared to the K non-carriers [20]. They also reported that MMSE scores were lower in subjects with low CSF BChE activity in APOE4 carriers [5].

Our case-control study has several limitations. Although this dataset represents the largest and longest pharmacogenetic dataset of BChE-K in MCI, it is nevertheless limited by the size of the BChE homozygous groups and by its retrospective nature. In addition, the study population was a typical sample of a clinical trial for MCI who are in general healthier than the general population due to strict inclusion/exclusion criteria. The study was composed mainly of non-Hispanic Caucasians which also limits the generalizability of our findings. Despite these limitations, our findings are in agreement with results reported recently by Han et al. with the use of rivastigmine [16]. In their case-only study, they found that the BChE-K allele was a significant predictor of poor rivastigmine response in Korean AD dementia patients [16]. Hence, poor response associated with the BChE-K variant might be seen with all medications from the AChEI class and not just with donepezil as we found here. Yet, other case-only pharmacogenetic studies failed to detect an interaction between BChE K-genotype and AChEI effect on cognitive function response in late onset AD (LOAD) [11, 15]. It is important to point out that both the sample size and the duration of these LOAD studies were much smaller than the cohort we analyzed here [Table 2], which might explain their negative findings. However, the largest of the three did see an effect of genotype on response to therapy but the authors could not determine whether the treatment was deleterious in BChE-K demented subjects since they did not have a placebo group [16]. In their study, they reported a lower response rate among APOE4 carriers treated with rivastigmine, with no difference among APOE4 non-carriers [16].

Table 2.

BChE Pharmacogenetic studies of AChEI response in Late Onset Alzheimer’s Disease

| N per BChE genotype |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Study | Ethnicity | AChEI | Treatment duration |

Placebo control |

Outcome varibales |

K0 | K1 | K2 | P value |

|

| |||||||||

| Scacchi et al. 2008 [1] | Caucasian | Donepezil | 15-months | No | MMSE | 64 | 32 | 4 | >0.05 |

| Rivastigmine | MMSE | 41 | 28 | 0 | > 0.05 | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Han et al. [2] | Asian | Rivastigmine alone or with memantine | 16 weeks | No | MMSE | 111 | 35 | >0.05 | |

| ADAS-cog | 111 | 35 | <0.001** | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Blesa et al. [3] | Caucasian | Donepezil | 2 years | No | MMSE | 43 | 19 | >0.05 | |

| Rivastigmine | MMSE | 33 | 19 | >0.05 | |||||

K genotype: K0 denotes the absence of the K allele, K1 is for the heterozygous carriers and K2 for the homozygous carriers.

In conclusion, our data indicate that rs1803274 is a pharmacogenetic marker of donepezil response in MCI. BChE genotyping of locus rs180327 is valuable in detecting individuals who are likely to demonstrate a faster cognitive decline in MCI if treated with donepezil, and principally in those carrying the APOE4 allele. Thus, this opens up the discussion of the off-label use of AChEIs in MCI and offers the prospect of rationalized pharmacogenetic approaches for personalized-medicine in the treatment of individuals with MCI when there is no alternative to AChEIs. We conclude that BChE-K genotype should be routinely tested and that donepezil should not be prescribed off-label to BChE K-variant carriers, especially in APOE4 carriers, as it leads to disease exacerbation and faster cognitive decline in MCI.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Patients’ demographic information at baseline

| Donepezil treated | Donepezil naive | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 193 (33.6%) | 381 (66.4%) | |

| Age (SD) | 73.19 (6.80) | 72.77 (8.26) | 0.74 |

| Male (%) | 105 (54.4%) | 204 (53.5%) | 0.86 |

| APOE4 (%) | 87 (45.1%) | 183 (48.0%) | 0.53 |

| MMSE (SD) | 27.3 (1.8) | 27.3 (1.8) | |

| CDR-SB (SD) | 1.8 (0.8) | 1.8 (0.7) |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIA 1K23AG051416-01A1 and UCLA School of Nursing intramural grants to SS; R01 AG040770 and K02 AG 048240 to LGA. Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study (U01 AG10483/AG/NIA). UCLA Alzheimer's Disease research center P50 AG16570. INDIANA Alzheimer's Disease center P30 AG010133.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Conception and design of the study: S.S, X.L, K.D.T, J.I.R, R.A.R, P.S.A, L.G.A. Acquisition and analysis of data: S.S, L.C, X.L, K.T, J.R, R.A.R, P.S.A, L.G.A. Drafting the manuscript or figures: S.S, L.C, X.L, K.T, J.I.R and L.G.A.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

Nothing to report.

Bibliography

- 1.Petersen RC, Parisi JE, Dickson DW, Johnson KA, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Jicha GA, Ivnik RJ, Smith GE, Tangalos EG, Braak H, Kokmen E. Neuropathologic features of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:665–672. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.5.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersen RC, Thomas RG, Grundman M, Bennett D, Doody R, Ferris S, Galasko D, Jin S, Kaye J, Levey A, Pfeiffer E, Sano M, van Dyck CH, Thal LJ, Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study G Vitamin E and donepezil for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2379–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jicha GA, Parisi JE, Dickson DW, Johnson K, Cha R, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Boeve BF, Knopman DS, Braak H, Petersen RC. Neuropathologic outcome of mild cognitive impairment following progression to clinical dementia. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:674–681. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.5.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cacabelos R. Donepezil in Alzheimer's disease: From conventional trials to pharmacogenetics. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3:303–333. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ballard CG. Advances in the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease: Benefits of Dual Cholinesterase Inhibition. European Neurology. 2002;47:64–70. doi: 10.1159/000047952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Podoly E, Shalev DE, Shenhar-Tsarfaty S, Bennett ER, Ben Assayag E, Wilgus H, Livnah O, Soreq H. The Butyrylcholinesterase K Variant Confers Structurally Derived Risks for Alzheimer Pathology. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284:17170–17179. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.004952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darvesh S, Hopkins DA, Geula C. Neurobiology of butyrylcholinesterase. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:131–138. doi: 10.1038/nrn1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bizzarro A, Guglielmi V, Lomastro R, Valenza A, Lauria A, Marra C, Silveri MC, Tiziano FD, Brahe C, Masullo C. BuChE K variant is decreased in Alzheimer's disease not in fronto-temporal dementia. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2010;117:377–383. doi: 10.1007/s00702-009-0358-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raygani AV, Zahrai M, Soltanzadeh A, Doosti M, Javadi E, Pourmotabbed T. Analysis of association between butyrylcholinesterase K variant and apolipoprotein E genotypes in Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett. 2004;371:142–146. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scacchi R, Gambina G, Moretto G, Corbo RM. Variability of AChE, BChE, and ChAT genes in the late-onset form of Alzheimer's disease and relationships with response to treatment with Donepezil and Rivastigmine. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009;150B:502–507. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehmann DJ, Johnston C, Smith AD. Synergy between the genes for butyrylcholinesterase K variant and apolipoprotein E4 in late-onset confirmed Alzheimer's disease. Human Molecular Genetics. 1997;6:1933–1936. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.11.1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panegyres PK, Mamotte CD, Vasikaran SD, Wilton S, Fabian V, Kakulas BA. Butyrycholinesterase K variant and Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol. 1999;246:369–370. doi: 10.1007/s004150050365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giedraitis V, Kilander L, Degerman-Gunnarsson M, Sundelöf J, Axelsson T, Syvänen AC, Lannfelt L, Glaser A. Genetic Analysis of Alzheimer’s Disease in the Uppsala Longitudinal Study of Adult Men. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2009;27:59–68. doi: 10.1159/000191203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blesa R, Bullock R, He Y, Bergman H, Gambina G, Meyer J, Rapatz G, Nagel J, Lane R. Effect of butyrylcholinesterase genotype on the response to rivastigmine or donepezil in younger patients with Alzheimer's disease. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2006;16:771–774. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000220573.05714.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han HJ, Kwon JC, Kim JE, Kim SG, Park JM, Park KW, Park KC, Park KH, Moon SY, Seo SW, Choi SH, Cho SJ. Effect of rivastigmine or memantine add-on therapy is affected by butyrylcholinesterase genotype in patients with probable Alzheimer's disease. Eur Neurol. 2015;73:23–28. doi: 10.1159/000366198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mesulam MM, Guillozet A, Shaw P, Levey A, Duysen EG, Lockridge O. Acetylcholinesterase knockouts establish central cholinergic pathways and can use butyrylcholinesterase to hydrolyze acetylcholine. Neuroscience. 2002;110:627–639. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00613-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartmann J, Kiewert C, Duysen EG, Lockridge O, Greig NH, Klein J. Excessive hippocampal acetylcholine levels in acetylcholinesterase-deficient mice are moderated by butyrylcholinesterase activity. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2007;100:1421–1429. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Darreh-Shori T, Brimijoin S, Kadir A, Almkvist O, Nordberg A. Differential CSF butyrylcholinesterase levels in Alzheimer's disease patients with the ApoE epsilon4 allele, in relation to cognitive function and cerebral glucose metabolism. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;24:326–333. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Darreh-Shori T, Siawesh M, Mousavi M, Andreasen N, Nordberg A. Apolipoprotein ε4 Modulates Phenotype of Butyrylcholinesterase in CSF of Patients with Alzheimer's Disease. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2012;28:443–458. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-111088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.