Abstract

Purpose

To report the prevalence of anisometropia at age 5 years after unilateral intraocular lens (IOL) implantation in infants.

Design

Prospective randomized clinical trial

Methods

Fifty-seven infants in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study (IATS) with a unilateral cataract were randomized to IOL implantation with an initial targeted postoperative refractive error of either +8D (infants 28 to <48 days of age) or +6D (infants 48–210 days of age). Anisometropia was calculated at age 5 years. Six patients were excluded from the analyses.

Results

Median age at cataract surgery was 2.2 months (IQR, 1.2, 3.5 months). The mean age at the age 5 year follow-up visit was 5.0 ± 0.1 years (range, 4.9 – 5.4 years). The median refractive error at the age 5 year visit of the treated eyes was −2.25 D (IQR −5.13, +0.88 D) and of the fellow eyes +1.50 D (IQR +0.88, +2.25). Median anisometropia was −3.50 D (IQR −8.25, −0.88 D); range (−19.63 to +2.75D). Patients with glaucoma in the treated eye (n=9) had greater anisometropia (glaucoma, median −8.25 D; IQR −11.38, −5.25 D vs. no glaucoma median −2.75; IQR −6.38, −0.75 D; p=0.005)

Conclusions

The majority of pseudophakic eyes had significant anisometropia at age 5 years. Anisometropia was greater in patients that developed glaucoma. Variability in eye growth and myopic shift continue to make refractive outcomes challenging for IOL implantation during infancy.

Introduction

The human eye usually experiences 3–4 mm of axial elongation during the first year of life.1–3 Concurrently, the cornea and crystalline lens flatten, resulting in a relatively stable refractive error. The myopic shift induced by axial elongation following infantile cataract surgery cannot be fully offset by corneal flattening. In aphakic eyes, the myopic shift can easily be corrected as needed by reducing the power of corrective contact lenses or spectacles.4, 5 Small myopic shifts can also be corrected with contact lenses or spectacles in pseudophakic eyes; however, large myopic shifts may necessitate an IOL exchange. 6 In children with unilateral pseudophakia, a large myopic shift may result in significant anisometropia that can impair binocularity and worsen amblyopia, particularly when the IOL is implanted at an early age. While there is no agreement regarding the optimal refractive error after IOL implantation during infancy, most clinicians target an undercorrection in anticipation of a myopic shift.7–11

While small case series have reported a mean myopic shift ranging from 5 to 7 D after IOL implantation during infancy, these studies were retrospective with variable lengths of follow-up.12–15 The Infant Aphakia Treatment Study (IATS) is a randomized clinical trial comparing the visual outcome in infants 1–6 months of age undergoing unilateral cataract surgery who underwent primary implantation of an intraocular lens (IOL) versus being left aphakic and receiving a contact lens correction.16 We report the anisometropia present at age 5 years in children randomized to IOL correction in the IATS.

Methods

The study design, surgical technique, follow-up schedules, patching and optical correction regimens, and examination methods have been reported in detail previously and are only summarized in this report. 17 The study followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review boards of the participating institutions and was in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. The off-label research use of the Acrysof SN60AT and MA60AC IOLs (Alcon Laboratories, Fort Worth, Texas) was covered by US Food and Drug Administration investigational device exemption # G020021. The IATS is a randomized clinical trial (clinicaltrials.gov Identifier NCT00212134).

Infants randomized to the IOL group had their IOL power calculated using the Holladay 1 formula targeting an 8 D under correction (residual hypermetropia) for infants 28 to <48 days of age and 6 D under correction for infants aged 48–210 days. The definition of glaucoma used in the IATS has been described previously. 18,19 Refractive errors of the treated and fellow eye were measured after achieving cycloplegia with 1% cyclopentolate and 2.5% phenylephrine using retinoscopy or a table-top autorefractor (Nidek ARK-700A or Topcon RM-8800). Anisometropia was calculated at age 5 years using the spherical equivalent of refractive errors.

We analyzed several factors to determine if any of them correlated with anisometropia at the 5 year examination including the initial postoperative refraction of both the treated and fellow eyes, the refractive change of both the treated and fellow eyes at the age 5 year visit, the power of the implanted IOL, and the development of glaucoma. Spearman rank correlation was used to test the association of anisometropia at age 5 years versus refraction, change in refraction, and implanted IOL power. Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare the median anisometropia at age 5 years between those with and without glaucoma. A chi square analysis was used to compare anisometropia in eyes with and without glaucoma. The two group t-test was used to compare the presence or absence of stereopsis with the magnitude of anisometropia. For all analysis, a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used for all analysis.

Results

Of the 57 patients randomized to IOL implantation, 6 were excluded from the analysis: 3 patients who had an IOL exchange prior to age 5 years (Table 1), one patient who did not receive an IOL because the investigator decided intra-operatively that an IOL could not be safely implanted due to stretching of the ciliary processes not seen prior to surgery, one patient who had Stickler syndrome whose refractive changes would not be representative of the population studied, and one patient who was lost to follow-up.

Table 1.

Patients Undergoing IOL Exchange Prior to Age 5 Years

| Patient | Age at IOL exchange | Glaucomaor Glaucoma Suspect | Axial length (mm) at IOL Exchange | Refraction (SE) at IOL exchange | Original IOL Power(D) | Exchanged IOL Power (D) | Myopic shift after Exchange |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9 months | No | 20.36 | −7.50 | +35 | +24 | 1.5 D |

| 2 | 3.7 years | Yes | 25.74 | −19.00 | +33 | +13 | 0.625 D |

| 3 | 3.7 years | Yes | 24.54 | −8.50 | +30 | +20 | 3.50 D |

For the remaining 51 patients included in the analysis, median age at cataract surgery was 2.2 months (IQR 1.2, 3.4 months; range, 0.9 to 6.8 months). Their mean age at the age 5 year examination was 5.0 ± 0.1 years (range = 4.9 – 5.4 years). The median refractive error at the 5 year visit of the treated eyes was −2.25 D (IQR −5.13, +0.88 D) and of the fellow eyes +1.50 D (IQR +0.88, +2.25). Median anisometropia was −3.50 D (IQR −8.25, −0.88 D); and range (−19.63 to +2.75D). Table 2 summarizes the refractive error of treated and fellow eyes and anisometropia at age 5 years.

Table 2.

Refractive Error and Anisometropia at Age 5 Years

| Factor | n | Median (IQR) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Refractive Error – Treated Eye (D) | 51 | −2.25 (−5.13, +0.88) | −18.13 to + 5.00 |

| Refractive Error – Fellow Eye (D) | 51 | +1.50 (+0.88, +2.25) | −1.13 to +7.25 |

| Anisometropia (D) (Treated – Fellow) | 51 | −3.50 (−8.25, −0.88) | −19.63 to +2.75 |

Figures 1–3 also illustrate the refractive error at age 5 years in the treated and the fellow eye as well as the overall anisometropia.

Figure 1.

Bar graph showing spread of refractive errors in the pseudophakic eye at age 5 years.

Figure 3.

Bar graph showing spread of anisometropia between the treated and fellow eyes at age 5 years.

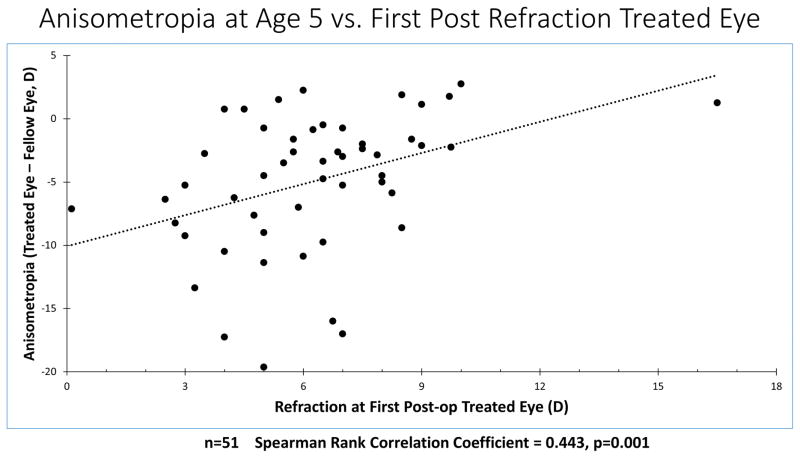

Table 3 summarizes the correlation between the amount of anisometropia at the age 5 years visit and the initial refraction and the change in refraction of both the treated and fellow eyes as well as the power of the implanted IOL. There was a significant correlation between both the initial refraction(Figure 4) and refractive change of the treated eye, but not with the refractive status of the fellow eye. This suggests that it was the initial and last refractive errors in the treated eyes, rather than the fellow eyes, that was primarily responsible for the anisometropia that developed in these patients. Additionally both a higher power implanted IOL (Figures 5) and the development of glaucoma were correlated with increased anisometropia at the 5 year visit. No correlation was found between the degree of anisometropia and the presence or absence of stereopsis (p=.628)

Table 3.

Anisometropia at Age 5 year vs. Other Factors

| First postoperative refraction | Treated eye n=51 |

Spearman rank correlation coefficient 0.44 | P=0.001 |

| First postoperative refraction | Fellow eye n=51 |

Spearman rank correlation coefficient −0.16 | P=0.26 |

| Change in refraction at 5 years | Treated eye n=51 |

Spearman rank correlation coefficient r=.72 | P<0.0001 |

| Change in refraction at 5 years | Fellow eye n=51 |

Spearman rank correlation coefficient r=0.13 | P=0.36 |

| Implanted IOL Power | Treated eye n=51 |

Spearman rank correlation coefficient r= −0.52 | P<0.0001 |

Figure 4.

Plot of the refractive error at the first postoperative refraction in the treated eye versus anisometropia at age 5 years.

Figure 5.

Plot of power of the intraocular lens implanted in the treated eye versus anisometropia at age 5 years.

Glaucoma was diagnosed in 9 of the 51 treated eyes and was associated with significantly greater anisometropia at the 5 year visit (glaucoma, median −8.25 D; IQR −11.38, −5.25 D vs. no glaucoma median −2.7 D5; IQR −6.38, −0.75 D; p=0.005) (Table 4). Additionally significantly fewer of the non-glaucoma patients developed ≥ 5 D of anisometropia at the 5 year visit (15/42 (36%)) compared to the patients that developed glaucoma (7/9 (78%)) (p-value=0.021).

Table 4.

Anisometropia (Treated Eye – Fellow Eye) at Age 5 Years vs Glaucoma

| Glaucoma | n | Anisometropia (Treated Eye – Fellow Eye, D) | p-value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Interquartile Range | Range | |||

| No | 42 | −2.75 | −6.38, −0.75 | −17.00, +2.75 | 0.0050 |

| Yes | 9 | −8.25 | −11.38, −5.25 | −19.63, −2.75 | |

p-value for the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test comparing the medians of the two groups.

Discussion

Variability of myopic shift after IOL implantation in infants continues to make IOL power selection challenging. In this series of infants that underwent unilateral IOL implantation when 1 to 6 months of age we noted significant postoperative anisometropia with the treated eye more myopic than the fellow eye in almost all cases. There was also great variability in the degree of anisometropia.

Several factors likely contributed to both the high variability and myopic bias (treated to fellow eye) of the anisometropia. First, our immediate postoperative refractive targets of +8D or +6D targets, which were based on an expected myopic shift derived from analysis of previous studies, 20–27 were not large enough to compensate for the actual myopic shift observed in many of these patients. Furthermore, greater myopic shift in the treated eye was highly correlated with greater anisometropia at the age 5 years visit. Secondly, as previously reported the initial one month postoperative refractions were on average slightly less hyperopic than the targeted undercorrection. In the younger age group with a targeted post-operative refraction of +8D, the mean one month postoperative refraction was +7.2 ±2.9 D and for the older age group targeted for a +6D undercorrection, +5.6D ±2.1 D. 28 A lower initial postoperative refraction (less hypermetropia) was also correlated with greater anisometropia at 5 years of age.

Little has been published previously regarding anisometropia following unilateral cataract surgery during infancy. Most authors have only reported the myopic shift in the pseudophakic eye 6. Kraus and coworkers reported performing IOL exchanges in 15 eyes following unilateral IOL implantation during infancy due to high myopia (mean, −9.6 D), however no mention was made of the refractive error in the fellow eye. Astle reported that 89% of patients with unilateral pseudophakia had 3 D or less of anisometropia after a mean follow-up of 3.16 years. However, their report included patients who underwent cataract surgery between 1 month and 18 years of age and they did not separate these different groups when evaluating anisometropia14.

Higher implanted IOL power was an additional factor associated with greater anisometropia at the age 5 years visit. As reported previously, 88% of eyes with implanted IOL power greater than 30D had less than anticipated postoperative hypermetropia which is correlated with greater anisometropia.28 Additionally as the eye grows axially the distance from the IOL to the retina increases and with implantation of higher powered IOLs the myopic shift is greater due to an optical phenomenon similar to the vertex distance. 29

A final factor to consider in excessive myopic shift and resultant myopia is the development of glaucoma which can result in increased axial length and myopic shift in young eyes 30–31 In this series, 9 of 51 (18%) eyes were diagnosed with glaucoma (two eyes with glaucoma were excluded because they had an IOL exchange) Eyes with glaucoma did have significantly more anisometropia with a median of −8.25 D vs. −2.75 D in the non-glaucomatous eyes. Eyes with glaucoma were more likely to have myopic anisometropia of ≥5D (78% vs. 36% in non-glaucomatous eyes) suggesting a role for glaucoma in at least some patients with excessive myopic shift.

Anisometropia is likely one of the factors that contributes to both amblyopia and decreased binocular function in children with unilateral pseudophakia. Weakley32 showed that 2 diopters or more of spherical myopic anisometropia and 1 diopter of more of spherical hypermetropic anisometropia significantly increased the incidence of amblyopia and decreased binocular function in children with naturally occurring anisometropia compared to nonanisometropic children. While we were unable to show a correlation between the presence and absence of stereopsis and the degree of anisometropia, this is not unexpected given the relatively low percentage of children who undergo unilateral cataract surgery who develop stereopsis. However, even if stereopsis is not improved by minimizing anisometropia, aniseikonia can be reduced and there are cosmetic benefits to having spectacle lenses that have similar powers.

The weaknesses of our study include its relatively small sample size that limited our ability to analyze subgroups and 3 patients having IOL exchanges before the end of the 5 year follow-up period. The strengths of the study included the prospective collection of refractive data using well defined protocols and the high follow-up rate.

Consideration should be given to trying to minimize anisometropia in children with unilateral pseudophakia by reducing the IOL power when the Holladay formula suggests an IOL power greater than 30 D for the standard postoperative hyperopic target for that age. In addition, closely monitoring the intraocular pressure of children after cataract surgery may allow glaucoma to be diagnosed and treated before excessive axial elongation occurs in these eyes thereby exacerbating the degree of anisometropia. Finally, targeting a higher postoperative hypermetropic refractive error may minimize the long-term anisometropia. We have recently shown that if the refractive goal is emmetropia at age 5 years, then the immediate postoperative refractive target should be +10.5 D for infants 4 to 6 weeks of age and +8.50 D for infants 7 weeks to 6 months for a child undergoing unilateral cataract surgery and IOL implantation.33 However, it should be emphasized that our ability to predict the myopic shift in a given child is limited at this time given the high degree of variability between individual children.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Bar graph showing spread of refractive errors in the fellow eye at age 5 years.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants U10 EY13272 and U10 EY013287, UG1 EY013272, UG1 EY025553 and supported in part by an unrestricted grant (no. UGIEY013272) from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc. New York, New York.

Financial Disclosures: No financial disclosures

Other: None

Footnotes

See Appendix for full listing of Infant Aphakia Treatment Study Group

Proprietary interests: none

Presented in part at the annual meeting of AAPOS on April 9, 2016 in Vancouver, Canada

References

- 1.Gordon RA, Donzis PB. Refractive development of the human eye. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103(6):785–789. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1985.01050060045020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manzitti E, Gamio S, Damel A, Benozzi J. Eye length in congenital cataracts. In: Cotlier E, Lambert S, Taylor D, editors. Congenital Cataracts. Austin, Texas: R.G. Landes Company; 1994. pp. 251–259. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley DV, Fernandes A, Lynn M, Tigges M, Boothe RG. Emmetropization in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta): birth to young adulthood. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40(1):214–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen RJ, Speedwell L, Russell-Eggitt I. Long-term visual outcome after extraction of unilateral congenital cataracts. Eye (Lond) 2010;24(7):1263–1267. doi: 10.1038/eye.2009.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen YC, Hu AC, Rosenbaum A, Spooner S, Weissman BA. Long-term results of early contact lens use in pediatric unilateral aphakia. Eye Contact Lens. 2010;36(1):19–25. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0b013e3181c6dfdc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kraus CL, Trivedi RH, Wilson ME. Intraocular lens exchange for high myopia in pseudophakic children. Eye (Lond) 2016;30(9):1199–1203. doi: 10.1038/eye.2016.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahan E, Drusedau MU. Choice of lens and dioptric power in pediatric pseudophakia. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1997;23(Suppl 1):618–623. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(97)80043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.BenEzra D. Cataract surgery and intraocular lens implantation in children, and intraocular lens implantation in children. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121(2):224–226. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70595-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Autrata R, Rehurek J, Vodickova K. Visual results after primary intraocular lens implantation or contact lens correction for aphakia in the first year of age. Ophthalmologica. 2005;219(2):72–79. doi: 10.1159/000083264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gouws P, Hussin HM, Markham RH. Long-term results of primary posterior chamber intraocular lens implantation for congenital cataract in the first year of life. Br J Ophthalmol 2006. 90(8):975–978. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.094656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thouvenin D, Nogue S, Fontes L, Arne JL. Long-term functional results of unilateral congenital cataract treatment with early surgery: 20 case studies. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2003;26(6):562–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashworth JL, Maino AP, Biswas S, Lloyd IC. Refractive outcomes after primary intraocular lens implantation in infants. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91(5):596–599. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.108571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lambert SR, Buckley EG, Plager DA, Medow NB, Wilson ME. Unilateral intraocular lens implantation during the first six months of life. J AAPOS. 1999;3(6):344–349. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(99)70043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Astle WF, Ingram AD, Isaza GM, Echeverri P. Paediatric pseudophakia: analysis of intraocular lens power and myopic shift. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2007;35(3):244–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McClatchey SK, Dahan E, Maselli E, et al. A comparison of the rate of refractive growth in pediatric aphakic and pseudophakic eyes. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(1):118–122. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambert SR, Buckley E, Drews-Botsch C, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing contact lens with intraocular lens correction of monocular aphakia during infancy: Grating acuity and adverse events at age 1 year. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(7):810–818. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Infant Aphakia Treatment Study Group. Lambert SR, Buckley EG, Drews-Botsch C, DuBois L, Hartmann E, Lynn MJ, Plager DA, Wilson ME. Infant aphakia treatment study: design and clinical measures at enrollment. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(1):21–27. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beck AD1, Freedman SF, Lynn MJ, Bothun E, Neely DE, Lambert SR Infant Aphakia Treatment Study Group. Glaucoma-related adverse events in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study: 1-year results. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(3):300–305. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freedman SF, Lynn MJ, Beck AD, Bothun ED, Örge FH, Lambert SR Infant Aphakia Treatment Study Group. Glaucoma related adverse events in the first 5 years of life after unilateral cataract removal in the infant aphakia treatment study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133(8):907–914. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McClatchey SK. Choosing IOL power in pediatric cataract surgery. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2010;50(4):115–123. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0b013e3181f0f2e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitmer S1, Xu A, McClatchey S. Reanalysis of refractive growth in pediatric Pseudophakia and Aphakia. J AAPOS. 2013;17(2):153–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crouch ER, Crouch ER, Jr, Pressman SH. Prospective analysis of pediatric pseudophakia: myopic shift and postoperative outcomes. J AAPOS. 2002;6(5):277–282. doi: 10.1067/mpa.2002.126492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Awner S, Buckley EG, DeVaro JM. Unilateral pseudophakia in children under 4 years. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1996;33(4):230–236. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19960701-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hutchinson AK, Drews-Botsch C, Lambert SR. Myopic shift after intraocular lens implantation during childhood. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(11):1752–1757. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yam JC, Wu PK, Ko ST, Wong US, Chan CW. Refractive changes after pediatric intraocular lens implantation in Hong Kong children. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2012;49(3):308–313. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20120501-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plager DR, Kipfer H, Sprunger DT, Sondi N, Neely DE. Refractive change in pediatric pseudophakia: 6-year follow-up. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2002;28(5):810–815. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(01)01156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ashworth JL, Maino AP, Biswas S, Lloyd IC. Refractive outcomes after primary intraocular lens implantation in infants. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91(5):596–599. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.108571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vanderveen DK, Nazam A, Lynn MJ, Bothun ED, McClatchey SK, Weakley DR, DuBois LG, Lambert SR Infant Aphakia Treatment Study Group. Predictability of intraocular lens calculation and early refractive status: the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(3):293–9. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McClatchey SK, Hofmeister EM. The optics of aphakic and psuedophakic eyes in childhood. Surv Ophthalmol. 2010;55(2):174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egbert KE, Kushner BJ. Excessive loss of hyperopia; presenting sign of juvenile aphakic glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108(9):1257–1259. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070110073027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson ME, Trivedi RH, Weakley DR, Lambert SR. Global axial length growth at age 5 years in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study. Ophthalmology. 2017 Feb 16; doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.12.040. pii: S0161-6420(16)30978-2. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weakley DR. The association between nonstrabismic anisometropia, amblyopia and subnormal binocularity. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(1):163–171. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00425-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weakley DR, Lynn MJ, Dubois L, Cotsonis G, Wilson ME, Buckley E, Plager DA, Lambert SR. Myopic shift 5 years after IOL implantation in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study. Ophthalmology. 2017 May;124(5):730–733. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.01.010. Epub 2017 Feb 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.