Abstract

The liver is a unique organ for homeostasis with regenerative capacities. Hepatocytes possess a remarkable capacity to proliferate upon injury; however, in more severe scenarios liver regeneration is believed to arise from at least one, if not several facultative hepatic progenitor cell (HPC) compartments. Newly-identified pericentral stem/progenitor cells residing around the central vein is responsible for maintaining hepatocyte homeostasis in the uninjured liver. In addition, HPCs have been reported to contribute to liver fibrosis and cancers. What drives liver homeostasis, regeneration and diseases is determined by the physiological and pathological conditions, and especially the HPC niches which influence the fate of HPCs. The HPC niches are special microenvironments consisting of different cell types, releasing growth factors and cytokines and receiving signals, as well as the extracellular matrix (ECM) scaffold. The HPC niches maintain and regulate stem cells to ensure organ homeostasis and regeneration. In recent studies, more evidence has been shown that hepatic cells such as hepatocytes, cholangiocytes or myofibroblasts can be induced to be oval cell-like state through transitions under some circumstance, those transitional cell types as potential liver-resident progenitor cells play important roles in liver pathophysiology. In this review, we describe and update recent advances in the diversity and plasticity of HPC and their niches and discuss evidence supporting their roles in liver homeostasis, regeneration, fibrosis and cancers.

Keywords: Hepatic stem/progenitor cells, Stem cell niche, Liver homeostasis, Liver regeneration

INTRODUCTION

The liver has an impressive regenerative capacity, and regeneration occurs through division of mature hepatocytes and cholangiocytes within the liver, which leave their normal mitotically quiescent state, termed G0, and enter cell cycle and mitosis.1 During persistent or severe liver injury, such as submassive necrosis, chronic viral hepatitis and non alcoholic fatty liver disease,2,3 this normally efficient renewal from mature epithelial cells is overwhelmed. In this scenario, adult hepatic stem/progenitor cells, termed hepatic progenitor cells (HPCs) in humans4 and oval cells in rodents,5 emerge and become activated.6,7 There cells, with a large nuclear-to–cytoplasm ratio and an oval-shaped nucleus, express markers of both biliary and hepatocyte lineages.8 Three-dimensional reconstructions in human liver suggest that HPCs arise from the interface between the hepatocyte canalicular system and the biliary tree, known as the canals of Hering (CoH).9 The CoH are partially lined by small hepatocytes and partially by bile duct epithelial cells. They are the physiologic link between the hepatocyte canalicular system and the biliary tree.10 This anatomical position of HPC accommodates their physiological role following activation, differentiating towards both hepatocellular and biliary type cells to restore function to the damaged liver.6 Recently new HPC and their niches have been identified, which are responsible for hepatocyte homeostasis in the uninjured liver.11 In addition, human and mouse hepatocytes can be induced to de-differentiate into ductular cells by ductular metaplasia in chronic injury; these hepatocyte-derived ducts display bipotent liver progenitors which can be differentiated into hepatocytes or cholangiocytes. This appears to involve transition through an “oval cell” like state,12 and these cell types are considered potential liver-resident progenitors. During liver injury some epithelial cells contribute to fibrogenesis by undergoing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT); moreover, it has been shown that certain mesenchymal cells can be reverted into epithelial cells by undergoing mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), and ultimately differentiate into either hepatocytes or cholangiocytes. Thus, it suggests that multiple cell types modulate the outcome of liver injury.13

On the other hand, it has also been reported that HPC may be transformed into cancer stem cells or tumor-initiating cells that drive tumor initiation and thus play a role in the tumorigenesis of hepatocellular carcinomas.14–16 In addition, some researchers have found co-expression of epithelial and mesenchymal markers in hepatic progenitor cells, demonstrating that HPC have an ability to differentiate towards hepatic stellate cells or myofibroblasts.17,18 Thus, these in vitro and in vivo results indicate that the fate of HPC depends not only upon which signaling cascades are activated within the HPC, but also on the disease context in which HPC evolve. HPC niches or microenvironments are critical in theses fate selections.

The concept of a stem cell niche was first developed by Raymond Schofield in 1978,19 who defined it as the microenvironment which regulates stem cell behavior including stem cell maintenance, self-renewal and differentiation. This paper seeks to provide an in-depth review of the literature regarding the role of the diversity and plasticity of HPC and their niche in maintaining the characteristics of HPCs and determining the fate choice of the HPC’s differentiation towards a specific cell type after activation.

The location and composition of HPC niche

In adult livers, the probable progenitor cell niche has been shown to reside in the most proximal biliary structures, the CoH.9,20 Support for the existence of the HPC niche in the CoH was provided by a lineage-tracing study in an HPC-mediated liver injury model, which showed a continuous supply of HPCs from the Sox9-expressing progenitor zone within the portal area.21 In addition to the CoH, other areas of the liver can also transiently provide a niche for HPCs, such as the space of Disse.22 General features of stem cell niches can be found in both the CoH and the space of Disse, but there are some differences between these two sites: One difference is that HPCs are directly exposed to high concentrations of bile acids in the CoH.23 In addition, the CoH appear to contain slow-cycling precursor cells in the normal liver,20,24 whereas the space of Disse normally contains quiescent stellate cells and hematopoietic stem cells that only rarely divide.22 Moreover, the type of cell which can release CXCL12 to attract chemokine cysteine-X-cysteine receptor 4 (CXCR4)-expressing cells in these two niches is different; they are liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LESC) in the space of Disse 25 and cholangiocytes in the CoH.26

However, it has been reported recently that newly-identified hepatic stem/progenitor cells resides around the central vein in normal liver,11 and the endothelial cells at the central vein produce Wnt2 and Wnt9b as short-range signals for these stem/progenitor cells, and constitute a portion of their niche. These pericentral stem/progenitor cells are distinct from aforementioned HSCs, as pericentral stem/progenitor cells maintain hepatocyte homeostasis in the uninjured liver while HSCs have only been reported after injury. Another difference is that pericentral stem/progenitor cells contribute only to the hepatocyte lineage rather than other liver cell types including biliary epithelial cells.11

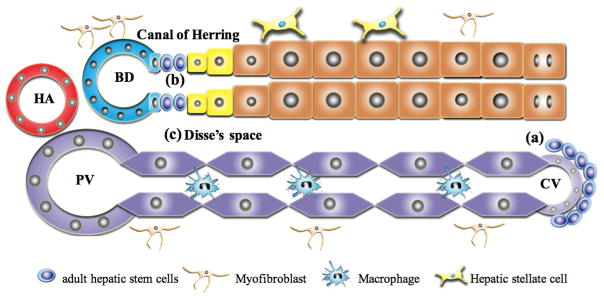

The HPC niche is defined not only by the site where it is located, but also by the composition of the niche (Figure 1). It is a special microenvironment consisted of different cell types, extracellular matrix (ECM) scaffold, growth factors and cytokines released by the niche cells and signaling pathways that help maintain the characteristics of HPCs and the balance among their activation, transition, proliferation and differentiation27–27 (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Model of the adult hepatic stem/progenitor cell niche.

(a): In the uninjured liver the Wnt-responsive stem cell population resides around the central vein. These cells self-renew and differentiate into hepatocytes and replace other hepatocytes for liver homeostasis. (b and c): In the injured liver, the canal of Herring (b) and the space of Disse (c) can provide a niches for adult HPCs. These niches are composed of different cell types, ECM components, growth factors and cytokines released by the niche cells and signaling pathways that help to maintain the characteristics of adult HPCs and control activation and proliferation, and govern differentiation fate decisions.

Figure 2. A schematic illustration shows that the activation and transition, proliferation and differentiation of the adult HPCs are determined by the factors and signals received.

Resident adult hepatic/stem cells are activated from their niche after receiving certain factors and signals or transitioned from hepatocytes or myofibroblasts by ductal metaplasia or MET (Left column); and proliferated (Central column); then differentiated towards hepatocytes by the activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling and the up-regulation of Wnt2 and Wnt9b, differentiated towards cholangiocytes by the activation of Notch signaling pathway, trans-differentiated into hepatic stellate cells by the up-regulation of TGF-β and CTGF, trans-differentiated into myofibroblasts by the up-regulation of Fox1 and TGF-β and the activation of non-canonial Wnt signaling pathway, and transformed into tumor-initiating cells by the up-regulation of TGF-β and Bmil and the activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (Right column). Abbreviations: MET, mesenchymal-epithelial transitions; HGF: hepatocyte growth factor; TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; EGF, epidermal growth factor; aFGF, acidic fibroblast growth factor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; IL-6: interleukin-6; LT-β: lymphotoxin β; LT-α: lymphotoxin α: IFN-α: interferon α; IFN-γ: interferon γ; TWEAK: TNF-like weak inducer of apoptosis; CTGF: connective tissue growth factor.

Markers of HPC

Accurately identifying HPC in vivo remains a major challenge in understanding HPC biology. To understand the complicated cross-talk between the different cell types and analyze their biological properties in detail, markers of HPC are required to track them at the single-cell level. In the many models of HPC activation it has been shown that numerous markers have been identified and employed (Table 1). However, their unequivocal identification and characterization as a pure fraction is a major obstacle in HPC research; some reported markers are not specific for HPCs and frequently these cells are confused with other cell types expressing the same genes. Therefore, further studies are required to explore unique and more versatile HPC-specific markers and genetic tools to achieve to clonal analyses of HPC.

Table 1.

Hepatic progenitor cell markers and references

| Hepatic progenitor cell markers | References |

|---|---|

| Rodents | |

| Cytokeratin 19 (CK19) | (105, 106) |

| CK7 | (107) |

| CK14 | (106) |

| γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase (γGT) | (108) |

| Glutathione-S-transferase P(GST-P) | (109) |

| OV6 | (110) |

| OV1 | (111) |

| A6 | (112) |

| OC.2 | (113) |

| OC.3 | (114) |

| Connexin 43 | (115) |

| CX3Cl1 | (116) |

| CD24 | (116) |

| MUC1 | (116) |

| Deleted in malignant brain tumour 1 | (117) |

| CD34 | (118) |

| c-kit | (119) |

| SerpinB3 | (120) |

| Foxl1 | (121) |

| Stromal-derived factor 1 (SDF1) | (122) |

| BDS7 | (123) |

| Albumin | (123) |

| CK8 | (124) |

| CK18 | (125) |

| Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 (HNF4) | (126) |

| HBD.1 | (127) |

| α-Fetoprotein (AFP) | (78) |

| Delta-like protein (dlk) | (128) |

| Aldolase A and C | (129, 130) |

| c-Met | (131) |

| Muscle pyruvate kinase (MPK) | (48) |

| Cadherin 22(PB-cadherin) | (116) |

| Cadherin 3(P-cadherin) | (116),129 |

| CD44 | (132) |

| Glutathione-S-transferase P (GST-P) | (109) |

| EpCAM | (133) |

| Glypican-3 | (134) |

| CXCR4 | (134) |

| Sca-1 | (111) |

| Thy-1(CD90) | (106) |

| Stromal-derived factor 1 (SDF1) | (135) |

| CD133 | (136) |

| chromogranin-A | (116) |

| parathyroid hormone-related peptide | (116) |

| Prox1 | (137) |

| Liv2 | (138) |

| Dlk | (139) |

| SEK1 | (140) |

| SMAD 5 | (141) |

| T-Box3(Tbx3) | (27) |

| Lgr5 | (142) |

| LIF | (143) |

| claudin-7 | (116) |

| claudin-22 | (116) |

| ros-1 | (116) |

| Gabrp | (116) |

| Podoplanin | (144) |

| Humans | |

| OV6 | (145) |

| EpCAM | (102) |

| CD133 | (131) |

| ALB | (146) |

| AFP | (146) |

| CK19 | (9, 102) |

| ICAM1 | (9) |

| CD44h | (102) |

| CD44 | (146) |

| CK8 | (102) |

| CK18 | (102) |

| c-kit | (102) |

| Dlk-1 | (9) |

| Prox1 | (145) |

| CD34 | (102, 137) |

| CD90 | (102) |

| c-met | (102) |

| SerpinB3 | (120) |

| GCTM-5 | (147) |

| α1-Antitrypsin | (123) |

| NCAM | (148) |

The neighboring cells with HPCs in the niche

Potentially all cell types in the liver can interact with HPCs including cholangiocytes, hepatocytes, stellate cells, myofibroblasts, Kupffer cells, LSECs, and cells from the immune system such as macrophages and lymphocytes. These cells are closely associated with HPCs and have a potential ability to influence the survival, proliferation, migration and differentiation of HPCs not only through secreting growth factors, chemokines, and cytokines,22,30,31 but also by direct cell-cell contracts.32

The epithelial cell types in liver, which incur the most damage, can influence the activation and the fate of HPCs to differentiate into hepatocytes and cholangiocytes. It has been demonstrated that in humans a threshold of 50% loss of hepatocytes is required for extensive HPC activation.33 In severe viral hepatitis and acute liver failure, the hepatocyte is the most damaged cell type, consequently HPCs differentiate into hepatocytes.34 In primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) and primary sclerosing cholangitis, the cholangiocyte is the primary damaged cell type, and HPCs differentiate towards biliary cells,35 though prior to cholangiocyte injury in the ducts, the CoH actually disappear, due to unknown causes. Thus, the loss of the CoH niche may be a primary event in the development of PBC.

In the uninjured liver, adjacent central vein endothelial-cell-derived Wnt signals (Wnt2 and Wnt9b) are necessary for maintaining the precursor state and the high proliferative state of pericentral stem/progenitor cells, and it appears that glutamine synthetase as a molecule important to niche maintenance in rodents and in humans.11

It has been shown that HPC expansion requires a close cooperation with accompanying hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) and myofibroblasts, which can produce hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), TGF-β, TGF-α, epidermal growth factor (EGF) and acidic fibroblast growth factor (aFGF).25,28,29,36,37 HSCs express signaling pathways required for HPC function such as hedgehog,38 Wnt/β-catenin39 and Notch signaling.25 Moreover, HSCs express the HPC marker CD133 and exhibit the capacity to differentiate into hepatocyte-like cells in vitro.40 Pintilie et al. have demonstrated that the inhibition of HSC activation after 2-AAF/partial hepatectomy (PHx) not only reduces HPC proliferation, but also affects HPC differentiation.41

Further invesitgations suggested that inflammatory cells played a central role in the HPC response, as multiple inflammatory cytokines were responsible for activating the HPC response.42 Lim, et al. found that IFN-α based treatment can reduce the number of HPCs in the choline-deficient ethionine-supplemented (CDE) diet model of chronic liver injury by modulating apoptosis, proliferation, and differentiation of HPCs.43 TNF-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK), a member of the pro-inflammatory TNF family, can be secreted by NK cells and macrophages, which stimulates the proliferation of HPCs through the activation of fibroblast growth factor-inducible 14 (Fn14) and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB).44 Nagyd et al. demonstrated that dexamethasone, a well-known inhibitor of TNF and IL-6, effectively inhibited HPC proliferation and liver regeneration after PHx.45 Knight et al. demonstrated that TNF signaling participated in the proliferation of HPCs during the preneoplastic phase of liver carcinogenesis, and inhibition of this signaling reduced the incidence of tumor formation.46 It has been reported that T lymphocytes and NK cells produced pro-inflammatory cytokines including IFN-γ and TNF-α, thereby promoting the expansion of HPCs in the CDE treatment model.47 LT-β, LT-β receptor, and IFN-γ are involved in HPC-mediated liver regeneration, and the absence of these cytokines impairs the HPC-dependent regenerative response.48 It has also been shown that HPC proliferation was reduced in TNF and LT-α double knockout mice.49 Yeoh et al, demonstrated that IL-6 administration resulted in increased migration and proliferation of HPC in vivo, and hyperactive STAT-3 signaling enhanced HPC numbers whereas ERK1/2 activation suppressed HPC proliferation.50 Inflammatory cells can also remodel the ECM through the production of metalloproteinases, a process that may be necessary for the extension of the HPC response.51 Thus there are a series of cell types which can interact and cross-talk with HPCs, thereby influencing the proliferative and differentiation capacities of HPC within the niche.

The extracellular matrix (ECM) in the HPC niche

The ECM is a structural network that consists of different types of collagens (types I, III, IV, V and XVIII),52 proteoglycans (heparan, dermatan, chondroitin sulphate, perlecan, hyaluronic acid, biglycan, and decorin)53 and glycoproteins (laminin, fibronectin, tenascin, nidogen, and SPARC).52 The ECM plays a vital role in the determination, differentiation, proliferation, and survival of HPCs by binding, integrating, and presenting growth factor signals to cells.54 A study using a CDE-induced murine model revealed that HPCs required ECM deposition and activation of matrix-producing cells, HSCs or myfibroblasts, for migration and differentiation for the repopulation of the damaged liver.55 They also demonstrated that new ECM deposition was an initial phase, prior to HPC expansion, along the porto-veinous gradient of lobular invasion, and that the ECM deposition played a fundamental role in establishing HPC niches. An in vitro study has demonstrated that HPCs can proliferate and maintain an undifferentiated phenotype when grown on laminin, but their proliferation was inhibited on collagen I matrix.56 It is intriguing to note that unlike any other epithelial lined structure in the body, the CoH-parenchymal interface has a discontinuous basement membrane: the biliary cells of the CoH having laminin-rich basement membrane while the adjoining hepatocytes only have loosely aggregated type 4 collagen fibers in their space of Dissse which may play a role in niche functionality.57 Moreover, an in vivo study has shown that a failure of ECM remodeling, i.e., fibrosis resolution and laminin deposition, hinders the ability of the liver to activate HPCs. In additions, laminin-HPC interactions within the HPC niche are critical for HPC activation and expansion.58 Future studies are necessary to better define the interactive cross-talk among HPCs, HSCs, myofibroblasts, and the ECM.

Signaling pathways in HPC and its niche

Determining which signals are responsible for such processes as induction of differentiation, self-renewal and/or maintenance of stemness will lead to a better understanding of the biology of HPCs and their role in liver regeneration. In the HPC niches, signaling pathways such as Wnt, Notch, and Hedgehog are key regulators of HPCs. β-catenin is an essential component of the canonical Wnt signaling, which is clearly involved in the HPC response observed in rodents and human. A noteworthy increase in total and active β-catenin was observed at the time of extensive oval cell activation and proliferation in the 2-AAF/PHx model. And a dramatic decrease of the A6-positive HPC numbers in the β-catenin conditional knockout mouse confirmed this role.59 The data from Yang et al. not only supported such a role for Wnt/β-catenin signaling in activation and proliferation of the HPCs in the liver, but also demonstrated that a considerable proportion of human HCCs appear to arise from HPCs, and activation of the Wnt/β-catenin can be markedly enriched in the HPC positive HCC cells.60 32 children with biopsy-proven non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) were studied to evaluate the role of Wnt3a production by macrophages in HPC response in the progression of pediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by Eugenio Gaudio’s team, they found that after pediatric patients were treated with docosahexaenoic acid, the macrophage polarization was determined to an anti-inflammatory phenotype with the upregulation of macrophage Wnt3a expression, resulting in reduction the degree of NAFLD and portal fibrosis through β-catenin phosphorylation in HPC and commitment towards hepatocyte fate.61

Notch signaling has also been shown to play a role in the differentiation and proliferation of oval cells in the rat model of 2AAF/PHx.62 Wang et al. found that Notch 3 is not only important in the generation of hepatocytes from fetal hepatic progenitor cells (FHPCs), but it also appears to be a potential marker of FHPCs.63 Also, Hedgehog (Hh) signaling is essential for survival of HPCs, as evidenced by an inhibitor of Hedgehog signaling, cyclopamine, which can induce HPC death.64 Another researches investigated the regulation of adult liver repair and regeneration, and liver diseases by Hh pathway,65–67 Hh pathway activation was accompanied by increased HPCs after PHx, and after treatment of mice with cyclopamine, a specific Smo antagonist, Hh signaling was inhibited and the expressions of various HPC markers were also reduced, indicating that Hh signaling is critical for normal liver regeneration.65 Leptin-deficient ob/ob mice with fatty livers and their healthy lean liver littermates were studied to determined if Hh signaling regulated HPCs and epithelial-mesenchymal transitions (EMT) during tissue remodeling before and after exposure to ethionine,66 the results showed that hepatic accumulation of HPCs which produced and responded to Hh ligands were increased in the ob/ob mice after treatment with ethionine, which resulted in increased Hh activity and liver fibrosis through EMT. Michelotti G et al, also demonstrated that Hh signaling was disrupted after Smoothened (SMO), an obligate intermediate in the Hh pathway, was conditionally deleted in α-SMA expressing cells in BDL mice, then inhibited fibrosis and caused liver atrophy by accumulation of myofibroblasts and HPCs, these all identify SMO was a master regulator of adult liver repair.67 In addition, it has been shown that the proliferation and self-renewal of human HPCs was promoted by the Bmi 1 pathway.68 And the clonogenicity of HPCs was significantly improved in culture medium containing the Rho-associated kinase inhibitor Y-27632.69 There is as yet no consensus as to which of these pathways is most critical in the function of the HPCs as well as their specific contributions to the HPC niche.

During liver development, epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM), a transmembrane glycoprotein, demonstrates a dynamic expression in fetal liver, including cells of the parenchyma, whereas mature hepatocytes are devoid of EpCAM. It has been demonstrated that liver regeneration is associated with a population of EpCAM-positive cells within ductular reactions, which gradually lose the expression of EpCAM along with maturation into hepatocytes.70,71 EpCAM can be switched on and off through a diverse panel of strategies to fine-tune EpCAM-dependent functional and differentiative traits. HPCs highly express EpCAM, and EpCAM is switched off in the derivatives of HPC. Thus, the molecular switches involved in the processes of HPC maintenance and differentiation into mature liver cells is of great consequence, but currently understudied. Based on the strong expression in HPCs and the dynamic expression pattern of EpCAM during liver cell differentiation and maturation, this molecule might represent a central target in the field of hepatocellular differentiation and liver regeneration.72

Experimental models of HPC activation

Since the first observation of HPCs as small, ovoid-shape cells reported to appear in the liver of rats, a series of experimental models of HPC-mediated liver regeneration in rodents have been employed.73 In rats, a precursor-product relationship exists between oval cells and hepatocytes with N-2-acetylaminofluorene (2-AAF) treatment. Oval cell activation, proliferation and differentiation resulting in the liver regeneration has been studied in a series of models, including the combination of 2-AAF with 70% hepatectomy (2-AAF/PHx),74 2-AAF treatment combined with exposure to carbon tetrachloride (2-AAF/CCl4),75 2-AAF treatment combined with allyl alcohol injury (2-AAF/AA),75 galactosamine (GalN) treatment,76 a choline-deficient, ethionine-supplemented (CDE) diet,77 and long-term exposure to ethanol.78 Recently, several models of HPC activation have been developed for mice, that are more genetically tractable than rats.79 For example, 1,4-bis[N,No-di-(ethylene)-phosphamide] piperazine (Dipin) treatment combined with 70% hepatectomy (Dipin/PHx),80 the CDE diet,79 galactosamine injury (GalN),81 allyl alcohol injury (AA),82 carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) injury,83 acetaminophen (APAP) injury,84 a 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine (DDC)-containing diet,85 and long-term exposure to ethanol have been employed.3 These approaches have been shown to be highly effective for the induction of hepatic oval cells capable of differentiating into hepatocytes and/or biliary epithelial cells, without causing high mortality. Of these, only APAP is a significant toxin in humans; indeed it is the leading cause for transplant for acute liver failure suggesting it should be more widely used as correlate to human disease. In humans, HPC activation is not observed after acute and complete extra-hepatic biliary obstruction, but HPC activation has been described in various conditions such as severe acute hepatitis due to viral infection, toxin (e.g. acetaminophen) or autoimmune hepatitis,10 chronic hepatitis B and C, primary biliary cirrhosis,86 alcoholic liver disease, chronic hepatitis B,87 fulminant hepatic failure, focal nodular hyperplasia, primary sclerosing cholangitis,88 and pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.89

The HPCs niche influences the fate of HPC differentiation

A handful of studies in recent years have shed light on factors and signals from the HPC niche that determine the fate choice of HPC differentiation to a specific cell type depending on the type and severity of the liver disease and resultant microenvironment created by it.90 HPCs are very different from tissue-resident progenitor cells in other epithelial tissues such as intestine and skin. They are not required to replenish liver tissue under normal, healthy conditions. Under the condition of liver parenchymal cells loss and impaired liver parenchymal cell proliferation, HPCs can differentiate into hepatocytes and cholangiocytes to restore parenchymal architecture and liver function.91 It has been shown that there can be robust hepatocyte repopulation by HPC in late stage human liver disease.70,92 Boulter et al. showed that Notch and Wnt signaling direct HPC specification within the activated myofibroblast and macrophage HPC niche in liver disease patients and murine models of the ductular reaction with biliary and hepatocyte regeneration. During adult biliary regeneration there is a requirement for an activated Notch signaling pathway in order to specify biliary epithelium from HPCs, while ectopic activation of the canonical Wnt pathway commits HPCs to the hepatocyte fate. Tanimizu et al. demonstrated that HPCs could differentiate into either hepatocytes or cholangiocytes by overlaying an Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm sarcoma (EHS) gel or by embedding them in a type I collagen gel, respectively.93 Inhibition of ECM accumulation resulted in an increased number of HPC-derived hepatocytes, suggesting that the ECM is also involved in the fate determination of HPCs.6 Wang et al. revealed that the fundamental mechanisms regulating liver renewal are similar to other organs in which homeostatic renewal involves small populations of stem/progenitor cells that maintain the tissue,11 and that these stem/progenitor cells only contribute to the hepatocyte lineage. In a recent study, Theise, ND et al. showed that the niche activities are sometimes simply responsible for the re-establishment of the hepato-biliary link. 57

Some studies have also suggested that deregulated HPCs might be a potential source of HCCs as well as cholangiocarcinomas (CC).94,95 As early as 2002, Dumble et al. demonstrated direct evidence for the involvement of HPCs in the pathogenesis of HCC. When HPCs, isolated from p53 null mice, were transplanted into athymic nude mice, they produced HCCs.96 Chiba et al. showed that the transplantation of Bmi1- or β-catenin-transduced cells clonally expanded from a single HPC produced tumors, which exhibited the histologic features of combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma.68 Wu et al revealed that TGF-β induced the neoplastic transformation of adult HSCs to hepatic TICs and facilitated HCCs.97 These observations imply that the dysregulated self-renewal of HPCs serves as an early event in hepatocarcinogenesis, and they also highlight the important roles of Bmi1 and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in regulating the self-renewal of normal or cancer stem cells in the liver. Our recent studies indicated that HPCs were the origin of a liver cancer stem cell formed by the fusion with hematopoietic precursor-derived myeloid intermediates,16 and these liver cancer stem cells could initiate three types of human liver carcinomas (HCC, CC and the combined HCC and CC (CHC)).98

Recent studies have clearly demonstrated that there is an association between the severity of fibrosis and progenitor cell activation.99 And some investigations have suggested that HPCs may not only make up for loss of hepatocytes but may also contribute to or promote periportal fibrogensis. For example, in the 2-AAF/PHx rat model, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) was up-regulated, and co-localized with HPCs and hepatic stellate cells.100 An HPC line, HPPL, derived from long-term culture of mouse Dlk+ hepatoblasts on laminin, can produce ECM proteins, including laminin-α5,-β1,-β2,-γ1, and -γ2 subunits.93 Some investigators found co-expression of epithelial and mesenchymal markers in hepatic progenitor cells, demonstrating that HPCs have an ability to differentiate towards hepatic stellate cells or myofibroblasts.17,101 Noemi et al. showed that expression profiling studies have identified a subpopulation of HPCs that express markers consistent with a mixed epithelial/ mesenchymal phenotype including members of the forkhead winged helix transcription factors family, Foxl 1.102 Yovchev et al. found that HPCs express a number of mesenchymal markers including vimentin, mesothelin, CD44, bone morphogenetic protein 7, and Tweak receptor (tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 12A).17 Wang et a.l demonstrated that freshly cultured HPCs can be induced by TGF-β1 to differentiate into mesenchymal cells, resembling hepatic stellate cells, through an EMT process.103 Dan et al. reported that multipotent progenitor cells isolated from human fetal liver were capable of differentiating into liver and mesenchymal lineages.102 Our recent study has shown that HPCs differentiated into α-SMA positive myofibroblasts via activation of the non-canonical Wnt pathway and exhibited a profibrotic effect in in the 2-AAF/CCl4 rat model.18 It also has been shown that HPCs can differentiate into pancreatic cells in the culture medium which was depleted with dexamethasome and supplemented with retinoic acid.93

Taken together, these reports suggest that HPCs are highly plastic cells which are capable of differentiating into hepatocytes, cholangiocytes, hepatic stellate cells, myofibroblasts and pancreatic cells, and can contribute to liver cancers depending on the HPC niche and the signals received.

CONCLUSION

Throughout life, the liver is bombarded with chemical, physiological and pathological insults which require the activation and appropriate differentiation of HPCs. To maintain liver homeostasis or restore the function of the damaged liver, the HPCs must differentiate into hepatocytes, the key metabolic cells of the liver, or/ and cholangiocytes, which line the biliary tree and transport bile into the intestine. In addition to resident hepatic progenitor cells, those transitional cell types as potential resident hepatic progenitor cells play important roles in liver regeneration after liver injury. However, on the other hand, HPCs contribute to liver fibrosis and cancers. The HPC niche regulates the maintenance of HPC quiescence, controls the activation and proliferation of HPCs, and governs fate decisions of HPC differentiation. Thus, the identification and elucidation of HPC niche composition, how it changes with liver injury and regeneration, as well as the interplay of its components in the normal and regenerating liver are pivotal for developing therapeutic strategies to enhance liver regeneration for a wide variety of human liver diseases (Table 2). In summary, the diversity and plasticity of HPCs and their niche interpret liver homeostasis, regeneration, fibrosis and cancers under physiological and pathological conditions (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Potential approaches to treat human liver diseases through modulation of adult hepatic progenitor cells and their niche

| Inhibit the transdifferentiation of HPC into myofibroblasts and/or hepatic stellate cells |

| Inhibit the transformation of HPCs into tumor-initiating cells |

| Stimulate the degradation of accumulated extracellular matrix in liver fibrosis* |

| HPC-based approaches promote hepatic regeneration |

Affect HPCs by modifying macrophage phenotype in vivo

|

: Inhibition of extracellular matrix accumulation could increase the number of HPC-derived hepatocytes.

Figure 3. A schematic illustration of the involvement of adult hepatic progenitor cells in liver disease.

Resident or transitional hepatic progenitor cells (HPC) will be differentiated towards hepatocytes or cholangiocytes under liver injury conditions such as in acute/chronic viral hepatitis, non-alcoholic and alcoholic steatohepatitis, or in primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis. Under some circumstance, HPCs can be trans-differentiated into myofibroblasts and/or hepatic stellate cells to contribute to the development and progression of liver fibrosis, and can be transformed into tumor initiating cells to initiate and sustain hepatocellular carcinoma, or cholangiocarcinoma, or both.

Since some investigations have shown that transplanted HPCs have the ability to differentiate into hepatocytes in vivo,104,105 HPC-based transplantation represents a therapeutic option which provides significant advantages compared to organ or primary hepatocyte transplantation. Thus, by adjusting the HPC microenvironment and optimizing the differentiation protocols, there is the potential to theoretically restore liver function as a clinical application in the future (Table 2).

Key Points.

HPC are responsible for liver homeostasis and regeneration. Under some circumstance, hepatic cells can be induced to function as potential liver-resident progenitors.

The canals of Hering, the space of Disse are and the central vein and their endothelial cells are defined with features of stem/progenitor cell niches.

The fate of HPC is determined by the interactions among extrinsic and intrinsic factors within HPC niche.

Extrinsic factors include different cell types, releasing growth factors, cytokines and receiving signals, and ECM scaffold in HPC niche.

Intrinsic factors mainly consist of activated signaling pathways in HPC, including Wnt, Notch, Hedgehog, and EpCAM pathways.

Acknowledgments

Financial support

This work is supported, in part, by Shanghai Sailing Program (16YF1411700) (to J.C), and, in part, by the NIH grant, DK075415 (to M.A.Z.), and, in part, by Innovative Seed Grant of American Liver Foundation, the NIH grant, R01 DK58559-01A1, SciArt Award of Wellcome Trust of United Kingdom, Singer-Hellman Research Grants of Beth Israel Medical Center of New York, Pilot and Feasibility Study of Marrion Bessin Liver Research Center from Albert Einstein College of Medicine (to N.D.T), and, in part, by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81530101) (to P.L), and, in part, by the NIH grants, DK077794, DK106633, DK113131, and AA010154 (to A.M.D).

Abbreviations

- HPC

hepatic progenitor cells

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EMT

epithelial to mesenchymal transition

- MET

mesenchymal to epithelial transition

- LSEC

liver sinusoidal endothelial cells

- PBC

primary biliary cholangitis

- CoH

canals of Hering

- HSC

hepatic stellate cells

- HGF

hepatocyte growth factor

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- aFGF

acidic fibroblast growth factor

- 2-AAF

N-2-acetylaminofluorene

- PHx

partial hepatectomy

- EpCAM

epithelial cell adhesion molecule

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinomas

- CC

cholangiocarcinomas

- TIC

tumor-initiating cells

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors do not have any disclosures to report.

References

- 1.BOULTER L, LU WY, FORBES SJ. Differentiation of progenitors in the liver: a matter of local choice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123(5):1867–73. doi: 10.1172/JCI66026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MARSHALL A, RUSHBROOK S, DAVIES SE, et al. Relation between hepatocyte G1 arrest, impaired hepatic regeneration, and fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(1):33–42. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ROSKAMS T, YANG SQ, KOTEISH A, et al. Oxidative stress and oval cell accumulation in mice and humans with alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Pathol. 2003;163(4):1301–11. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63489-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DE VOSR, DESMET V. Ultrastructural characteristics of novel epithelial cell types identified in human pathologic liver specimens with chronic ductular reaction. The American journal of pathology. 1992;140(6):1441–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.FARBER E. Similarities in the sequence of early histological changes induced in the liver of the rat by ethionine, 2-acetylamino-fluorene, and 3′-methyl-4-dimethylaminoazobenzene. Cancer Res. 1956;16(2):142–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ESPANOL-SUNER R, CARPENTIER R, VAN HULN, et al. Liver progenitor cells yield functional hepatocytes in response to chronic liver injury in mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(6):1564–75. e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.FELLOUS TG, ISLAM S, TADROUS PJ, et al. Locating the stem cell niche and tracing hepatocyte lineages in human liver. Hepatology. 2009;49(5):1655–63. doi: 10.1002/hep.22791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.THORGEIRSSON SS. Hepatic stem cells in liver regeneration. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 1996;10(11):1249–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.THEISE ND, SAXENA R, PORTMANN BC, et al. The canals of Hering and hepatic stem cells in humans. Hepatology. 1999;30(6):1425–33. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.GOUW AS, CLOUSTON AD, THEISE ND. Ductular reactions in human liver: diversity at the interface. Hepatology. 2011;54(5):1853–63. doi: 10.1002/hep.24613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WANG B, ZHAO L, FISH M, LOGAN CY, NUSSE R. Self-renewing diploid Axin2(+) cells fuel homeostatic renewal of the liver. Nature. 2015;524(7564):180–5. doi: 10.1038/nature14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.TARLOW BD, PELZ C, NAUGLER WE, et al. Bipotential adult liver progenitors are derived from chronically injured mature hepatocytes. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15(5):605–18. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.XIE G, DIEHL AM. Evidence for and against epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in the liver. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;305(12):G881–90. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00289.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.CAI X, ZHAI J, KAPLAN DE, et al. Background progenitor activation is associated with recurrence after hepatectomy of combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2012;56(5):1804–16. doi: 10.1002/hep.25874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.KOMUTA M, SPEE B, VANDER BORGHT S, et al. Clinicopathological study on cholangiolocellular carcinoma suggesting hepatic progenitor cell origin. Hepatology. 2008;47(5):1544–56. doi: 10.1002/hep.22238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ZENG C, ZHANG Y, PARK SC, et al. CD34(+) Liver Cancer Stem Cells Were Formed by Fusion of Hepatobiliary Stem/Progenitor Cells with Hematopoietic Precursor-Derived Myeloid Intermediates. Stem Cells Dev. 2015;24(21):2467–78. doi: 10.1089/scd.2015.0202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.YOVCHEV MI, GROZDANOV PN, ZHOU H, RACHERLA H, GUHA C, DABEVA MD. Identification of adult hepatic progenitor cells capable of repopulating injured rat liver. Hepatology. 2008;47(2):636–47. doi: 10.1002/hep.22047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.CHEN J, ZHANG X, XU Y, et al. Hepatic Progenitor Cells Contribute to the Progression of 2-Acetylaminofluorene/Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Cirrhosis via the Non-Canonical Wnt Pathway. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0130310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.SCHOFIELD R. The relationship between the spleen colony-forming cell and the haemopoietic stem cell. Blood cells. 1978;4(1–2):7–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.KUWAHARA R, KOFMAN AV, LANDIS CS, SWENSON ES, BARENDSWAARD E, THEISE ND. The hepatic stem cell niche: identification by label-retaining cell assay. Hepatology. 2008;47(6):1994–2002. doi: 10.1002/hep.22218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.FURUYAMA K, KAWAGUCHI Y, AKIYAMA H, et al. Continuous cell supply from a Sox9-expressing progenitor zone in adult liver, exocrine pancreas and intestine. Nature genetics. 2011;43(1):34–41. doi: 10.1038/ng.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.KORDES C, HAUSSINGER D. Hepatic stem cell niches. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123(5):1874–80. doi: 10.1172/JCI66027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.HUANG W, MA K, ZHANG J, et al. Nuclear receptor-dependent bile acid signaling is required for normal liver regeneration. Science. 2006;312(5771):233–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1121435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.ZHOU H, ROGLER LE, TEPERMAN L, MORGAN G, ROGLER CE. Identification of hepatocytic and bile ductular cell lineages and candidate stem cells in bipolar ductular reactions in cirrhotic human liver. Hepatology. 2007;45(3):716–24. doi: 10.1002/hep.21557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.SAWITZA I, KORDES C, REISTER S, HAUSSINGER D. The niche of stellate cells within rat liver. Hepatology. 2009;50(5):1617–24. doi: 10.1002/hep.23184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.TERADA R, YAMAMOTO K, HAKODA T, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor-1 from biliary epithelial cells recruits CXCR4-positive cells: implications for inflammatory liver diseases. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 2003;83(5):665–72. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000067498.89585.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.THEISE ND. Gastrointestinal stem cells. III. Emergent themes of liver stem cell biology: niche, quiescence, self-renewal, and plasticity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290(2):G189–93. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00041.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.ISHIKAWA T, FACTOR VM, MARQUARDT JU, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor/c-met signaling is required for stem-cell-mediated liver regeneration in mice. Hepatology. 2012;55(4):1215–26. doi: 10.1002/hep.24796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.NGUYEN LN, FURUYA MH, WOLFRAIM LA, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta differentially regulates oval cell and hepatocyte proliferation. Hepatology. 2007;45(1):31–41. doi: 10.1002/hep.21466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.BIRD TG, LORENZINI S, FORBES SJ. Activation of stem cells in hepatic diseases. Cell and tissue research. 2008;331(1):283–300. doi: 10.1007/s00441-007-0542-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.SPRADLING A, DRUMMOND-BARBOSA D, KAI T. Stem cells find their niche. Nature. 2001;414(6859):98–104. doi: 10.1038/35102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MORRISON SJ, SPRADLING AC. Stem cells and niches: mechanisms that promote stem cell maintenance throughout life. Cell. 2008;132(4):598–611. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.KATOONIZADEH A, NEVENS F, VERSLYPE C, PIRENNE J, ROSKAMS T. Liver regeneration in acute severe liver impairment: a clinicopathological correlation study. Liver international : official journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver. 2006;26(10):1225–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.FALKOWSKI O, AN HJ, IANUS IA, et al. Regeneration of hepatocyte ‘buds’ in cirrhosis from intrabiliary stem cells. J Hepatol. 2003;39(3):357–64. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.KHAN FM, KOMARLA AR, MENDOZA PG, BODENHEIMER HC, JR, THEISE ND. Keratin 19 demonstration of canal of Hering loss in primary biliary cirrhosis: “minimal change PBC”? Hepatology. 2013;57(2):700–7. doi: 10.1002/hep.26020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.EVARTS RP, HU Z, FUJIO K, MARSDEN ER, THORGEIRSSON SS. Activation of hepatic stem cell compartment in the rat: role of transforming growth factor alpha, hepatocyte growth factor, and acidic fibroblast growth factor in early proliferation. Cell Growth Differ. 1993;4(7):555–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.LEAHY DJ. Structure and function of the epidermal growth factor (EGF/ErbB) family of receptors. Adv Protein Chem. 2004;68:1–27. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(04)68001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.SICKLICK JK, LI YX, CHOI SS, et al. Role for hedgehog signaling in hepatic stellate cell activation and viability. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 2005;85(11):1368–80. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.KORDES C, SAWITZA I, HAUSSINGER D. Canonical Wnt signaling maintains the quiescent stage of hepatic stellate cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2008;367(1):116–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.KORDES C, SAWITZA I, MULLER-MARBACH A, et al. CD133+ hepatic stellate cells are progenitor cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2007;352(2):410–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.PINTILIE DG, SHUPE TD, OH SH, SALGANIK SV, DARWICHE H, PETERSEN BE. Hepatic stellate cells’ involvement in progenitor-mediated liver regeneration. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 2010;90(8):1199–208. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.KNIGHT B, MATTHEWS VB, AKHURST B, et al. Liver inflammation and cytokine production, but not acute phase protein synthesis, accompany the adult liver progenitor (oval) cell response to chronic liver injury. Immunology and cell biology. 2005;83(4):364–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.LIM R, KNIGHT B, PATEL K, MCHUTCHISON JG, YEOH GC, OLYNYK JK. Antiproliferative effects of interferon alpha on hepatic progenitor cells in vitro and in vivo. Hepatology. 2006;43(5):1074–83. doi: 10.1002/hep.21170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.TIRNITZ-PARKER JE, VIEBAHN CS, JAKUBOWSKI A, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis is a mitogen for liver progenitor cells. Hepatology. 2010;52(1):291–302. doi: 10.1002/hep.23663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.NAGY P, KISS A, SCHNUR J, THORGEIRSSON SS. Dexamethasone inhibits the proliferation of hepatocytes and oval cells but not bile duct cells in rat liver. Hepatology. 1998;28(2):423–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.KNIGHT B, YEOH GC, HUSK KL, et al. Impaired preneoplastic changes and liver tumor formation in tumor necrosis factor receptor type 1 knockout mice. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2000;192(12):1809–18. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.STRICK-MARCHAND H, MASSE GX, WEISS MC, DI SANTO JP. Lymphocytes support oval cell-dependent liver regeneration. Journal of immunology. 2008;181(4):2764–71. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.AKHURST B, MATTHEWS V, HUSK K, SMYTH MJ, ABRAHAM LJ, YEOH GC. Differential lymphotoxin-beta and interferon gamma signaling during mouse liver regeneration induced by chronic and acute injury. Hepatology. 2005;41(2):327–35. doi: 10.1002/hep.20520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.KNIGHT B, YEOH GC. TNF/LTalpha double knockout mice display abnormal inflammatory and regenerative responses to acute and chronic liver injury. Cell and tissue research. 2005;319(1):61–70. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-1003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.YEOH GC, ERNST M, ROSE-JOHN S, et al. Opposing roles of gp130-mediated STAT-3 and ERK-1/ 2 signaling in liver progenitor cell migration and proliferation. Hepatology. 2007;45(2):486–94. doi: 10.1002/hep.21535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.FALLOWFIELD JA, MIZUNO M, KENDALL TJ, et al. Scar-associated macrophages are a major source of hepatic matrix metalloproteinase-13 and facilitate the resolution of murine hepatic fibrosis. Journal of immunology. 2007;178(8):5288–95. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.SCHUPPAN D. Structure of the extracellular matrix in normal and fibrotic liver: collagens and glycoproteins. Semin Liver Dis. 1990;10(1):1–10. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1040452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.GRESSNER AM. Hepatic proteoglycans--a brief survey of their pathobiochemical implications. Hepato-gastroenterology. 1983;30(6):225–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.HYNES RO. The extracellular matrix: not just pretty fibrils. Science. 2009;326(5957):1216–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1176009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.VAN HULNK, ABARCA-QUINONES J, SEMPOUX C, HORSMANS Y, LECLERCQ IA. Relation between liver progenitor cell expansion and extracellular matrix deposition in a CDE-induced murine model of chronic liver injury. Hepatology. 2009;49(5):1625–35. doi: 10.1002/hep.22820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.LORENZINI S, BIRD TG, BOULTER L, et al. Characterisation of a stereotypical cellular and extracellular adult liver progenitor cell niche in rodents and diseased human liver. Gut. 2010;59(5):645–54. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.182345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.THEISE ND, DOLLE L, KUWAHARA R. Low hepatocyte repopulation from stem cells: a matter of hepatobiliary linkage not massive production. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):253–4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.KALLIS YN, ROBSON AJ, FALLOWFIELD JA, et al. Remodelling of extracellular matrix is a requirement for the hepatic progenitor cell response. Gut. 2011;60(4):525–33. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.224436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.APTE U, THOMPSON MD, CUI S, LIU B, CIEPLY B, MONGA SP. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling mediates oval cell response in rodents. Hepatology. 2008;47(1):288–95. doi: 10.1002/hep.21973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.YANG W, YAN HX, CHEN L, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling contributes to activation of normal and tumorigenic liver progenitor cells. Cancer research. 2008;68(11):4287–95. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.CARPINO G, NOBILI V, RENZI A, et al. Macrophage Activation in Pediatric Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) Correlates with Hepatic Progenitor Cell Response via Wnt3a Pathway. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.DARWICHE H, OH SH, STEIGER-LUTHER NC, et al. Inhibition of Notch signaling affects hepatic oval cell response in rat model of 2AAF-PH. Hepat Med. 2011;3:89–98. doi: 10.2147/HMER.S12368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.WANG T, YOU N, TAO K, et al. Notch is the key factor in the process of fetal liver stem/progenitor cells differentiation into hepatocytes. Development, growth & differentiation. 2012;54(5):605–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2012.01363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.SICKLICK JK, LI YX, MELHEM A, et al. Hedgehog signaling maintains resident hepatic progenitors throughout life. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290(5):G859–70. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00456.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.OCHOA B, SYN WK, DELGADO I, et al. Hedgehog signaling is critical for normal liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in mice. Hepatology. 2010;51(5):1712–23. doi: 10.1002/hep.23525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.FLEIG SV, CHOI SS, YANG L, et al. Hepatic accumulation of Hedgehog-reactive progenitors increases with severity of fatty liver damage in mice. Lab Invest. 2007;87(12):1227–39. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.MICHELOTTI GA, XIE G, SWIDERSKA M, et al. Smoothened is a master regulator of adult liver repair. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(6):2380–94. doi: 10.1172/JCI66904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.CHIBA T, ZHENG YW, KITA K, et al. Enhanced self-renewal capability in hepatic stem/progenitor cells drives cancer initiation. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(3):937–50. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.KAMIYA A, KAKINUMA S, YAMAZAKI Y, NAKAUCHI H. Enrichment and clonal culture of progenitor cells during mouse postnatal liver development in mice. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(3):1114–26. 26 e1–14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.YOON SM, GERASIMIDOU D, KUWAHARA R, et al. Epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) marks hepatocytes newly derived from stem/progenitor cells in humans. Hepatology. 2011;53(3):964–73. doi: 10.1002/hep.24122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.GIRES O. EpCAM in hepatocytes and their progenitors. J Hepatol. 2012;56(2):490–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.DOLLE L, THEISE ND, SCHMELZER E, BOULTER L, GIRES O, VAN GRUNSVEN LA. EpCAM and the biology of hepatic stem/progenitor cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015;308(4):G233–50. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00069.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.KINOSITA R. Studies on the Cancerogenic Azo and Related Compounds. Yale J Biol Med. 1940;12(3):287–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.EVARTS RP, NAGY P, MARSDEN E, THORGEIRSSON SS. A precursor-product relationship exists between oval cells and hepatocytes in rat liver. Carcinogenesis. 1987;8(11):1737–40. doi: 10.1093/carcin/8.11.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.PETERSEN BE, ZAJAC VF, MICHALOPOULOS GK. Hepatic oval cell activation in response to injury following chemically induced periportal or pericentral damage in rats. Hepatology. 1998;27(4):1030–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.LEMIRE JM, SHIOJIRI N, FAUSTO N. Oval cell proliferation and the origin of small hepatocytes in liver injury induced by D-galactosamine. Am J Pathol. 1991;139(3):535–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.SELL S, LEFFERT HL, SHINOZUKA H, LOMBARDI B, GOCHMAN N. Rapid development of large numbers of alpha-fetoprotein-containing “oval” cells in the liver of rats fed N-2-fluorenylacetamide in a choline-devoid diet. Gan. 1981;72(4):479–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.SMITH PG, TEE LB, YEOH GC. Appearance of oval cells in the liver of rats after long-term exposure to ethanol. Hepatology. 1996;23(1):145–54. doi: 10.1002/hep.510230120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.AKHURST B, CROAGER EJ, FARLEY-ROCHE CA, et al. A modified choline-deficient, ethionine-supplemented diet protocol effectively induces oval cells in mouse liver. Hepatology. 2001;34(3):519–22. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.26751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.FACTOR VM, RADAEVA SA, THORGEIRSSON SS. Origin and fate of oval cells in dipin-induced hepatocarcinogenesis in the mouse. Am J Pathol. 1994;145(2):409–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.KONIARIS LG, ZIMMERS-KONIARIS T, HSIAO EC, CHAVIN K, SITZMANN JV, FARBER JM. Cytokine-responsive gene-2/IFN-inducible protein-10 expression in multiple models of liver and bile duct injury suggests a role in tissue regeneration. J Immunol. 2001;167(1):399–406. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.1.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.LEE JH, ILIC Z, SELL S. Cell kinetics of repair after allyl alcohol-induced liver necrosis in mice. Int J Exp Pathol. 1996;77(2):63–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2613.1996.00964.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.ENGELHARDT NV, BARANOV VN, LAZAREVA MN, GOUSSEV AI. Ultrastructural localisation of alpha-fetoprotin (AFP) in regenerating mouse liver poisoned with CCL4. 1. Reexpression of AFP in differentiated hepatocytes. Histochemistry. 1984;80(4):401–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00495425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.KOFMAN AV, MORGAN G, KIRSCHENBAUM A, et al. Dose- and time-dependent oval cell reaction in acetaminophen-induced murine liver injury. Hepatology. 2005;41(6):1252–61. doi: 10.1002/hep.20696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.WANG X, FOSTER M, AL-DHALIMY M, LAGASSE E, FINEGOLD M, GROMPE M. The origin and liver repopulating capacity of murine oval cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(Suppl 1):11881–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1734199100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.SPEE B, CARPINO G, SCHOTANUS BA, et al. Characterisation of the liver progenitor cell niche in liver diseases: potential involvement of Wnt and Notch signalling. Gut. 2010;59(2):247–57. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.188367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.PORRETTI L, CATTANEO A, COLOMBO F, et al. Simultaneous characterization of progenitor cell compartments in adult human liver. Cytometry A. 2010;77(1):31–40. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.TURANYI E, DEZSO K, CSOMOR J, SCHAFF Z, PAKU S, NAGY P. Immunohistochemical classification of ductular reactions in human liver. Histopathology. 2010;57(4):607–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.NOBILI V, CARPINO G, ALISI A, et al. Hepatic progenitor cells activation, fibrosis, and adipokines production in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2012;56(6):2142–53. doi: 10.1002/hep.25742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.KATOONIZADEH A, POUSTCHI H. Adult Hepatic Progenitor Cell Niche: How it affects the Progenitor Cell Fate. Middle East journal of digestive diseases. 2014;6(2):57–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.BOULTER L, GOVAERE O, BIRD TG, et al. Macrophage-derived Wnt opposes Notch signaling to specify hepatic progenitor cell fate in chronic liver disease. Nat Med. 2012;18(4):572–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.LIN WR, LIM SN, MCDONALD SA, et al. The histogenesis of regenerative nodules in human liver cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2010;51(3):1017–26. doi: 10.1002/hep.23483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.TANIMIZU N, SAITO H, MOSTOV K, MIYAJIMA A. Long-term culture of hepatic progenitors derived from mouse Dlk+ hepatoblasts. Journal of cell science. 2004;117(Pt 26):6425–34. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.LEE JS, HEO J, LIBBRECHT L, et al. A novel prognostic subtype of human hepatocellular carcinoma derived from hepatic progenitor cells. Nature medicine. 2006;12(4):410–6. doi: 10.1038/nm1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.SELL S, DUNSFORD HA. Evidence for the stem cell origin of hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. The American journal of pathology. 1989;134(6):1347–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.DUMBLE ML, CROAGER EJ, YEOH GC, QUAIL EA. Generation and characterization of p53 null transformed hepatic progenitor cells: oval cells give rise to hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23(3):435–45. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.3.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.WU K, DING J, CHEN C, et al. Hepatic transforming growth factor beta gives rise to tumor-initiating cells and promotes liver cancer development. Hepatology. 2012;56(6):2255–67. doi: 10.1002/hep.26007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.PARK SC, NGUYEN NT, EUN JR, et al. Identification of cancer stem cell subpopulations of CD34(+) PLC/PRF/5 that result in three types of human liver carcinomas. Stem Cells Dev. 2015;24(8):1008–21. doi: 10.1089/scd.2014.0405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.KNIGHT B, AKHURST B, MATTHEWS VB, et al. Attenuated liver progenitor (oval) cell and fibrogenic responses to the choline deficient, ethionine supplemented diet in the BALB/c inbred strain of mice. Journal of hepatology. 2007;46(1):134–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.PI L, OH SH, SHUPE T, PETERSEN BE. Role of connective tissue growth factor in oval cell response during liver regeneration after 2-AAF/PHx in rats. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(7):2077–88. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.SICKLICK JK, CHOI SS, BUSTAMANTE M, et al. Evidence for epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in adult liver cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291(4):G575–83. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00102.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.DAN YY, RIEHLE KJ, LAZARO C, et al. Isolation of multipotent progenitor cells from human fetal liver capable of differentiating into liver and mesenchymal lineages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(26):9912–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603824103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.WANG P, LIU T, CONG M, et al. Expression of extracellular matrix genes in cultured hepatic oval cells: an origin of hepatic stellate cells through transforming growth factor beta? Liver international : official journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver. 2009;29(4):575–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.01992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.DORRELL C, ERKER L, SCHUG J, et al. Prospective isolation of a bipotential clonogenic liver progenitor cell in adult mice. Genes & development. 2011;25(11):1193–203. doi: 10.1101/gad.2029411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.SUZUKI A, SEKIYA S, ONISHI M, et al. Flow cytometric isolation and clonal identification of self-renewing bipotent hepatic progenitor cells in adult mouse liver. Hepatology. 2008;48(6):1964–78. doi: 10.1002/hep.22558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.BISGAARD HC, PARMELEE DC, DUNSFORD HA, SECHI S, THORGEIRSSON SS. Keratin 14 protein in cultured nonparenchymal rat hepatic epithelial cells: characterization of keratin 14 and keratin 19 as antigens for the commonly used mouse monoclonal antibody OV-6. Mol Carcinog. 1993;7(1):60–6. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940070110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.PAKU S, DEZSO K, KOPPER L, NAGY P. Immunohistochemical analysis of cytokeratin 7 expression in resting and proliferating biliary structures of rat liver. Hepatology. 2005;42(4):863–70. doi: 10.1002/hep.20858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.PETERSEN BE, GOFF JP, GREENBERGER JS, MICHALOPOULOS GK. Hepatic oval cells express the hematopoietic stem cell marker Thy-1 in the rat. Hepatology. 1998;27(2):433–45. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.TEE LB, SMITH PG, YEOH GC. Expression of alpha, mu and pi class glutathione S-transferases in oval and ductal cells in liver of rats placed on a choline-deficient, ethionine-supplemented diet. Carcinogenesis. 1992;13(10):1879–85. doi: 10.1093/carcin/13.10.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.CROSBY HA, HUBSCHER SG, JOPLIN RE, KELLY DA, STRAIN AJ. Immunolocalization of OV-6, a putative progenitor cell marker in human fetal and diseased pediatric liver. Hepatology. 1998;28(4):980–5. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.SANCHEZ A, FACTOR VM, SCHROEDER IS, NAGY P, THORGEIRSSON SS. Activation of NF-kappaB and STAT3 in rat oval cells during 2-acetylaminofluorene/partial hepatectomy-induced liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2004;39(2):376–85. doi: 10.1002/hep.20040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.PETERSEN BE, GROSSBARD B, HATCH H, PI L, DENG J, SCOTT EW. Mouse A6-positive hepatic oval cells also express several hematopoietic stem cell markers. Hepatology. 2003;37(3):632–40. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.FARIS RA, MONFILS BA, DUNSFORD HA, HIXSON DC. Antigenic relationship between oval cells and a subpopulation of hepatic foci, nodules, and carcinomas induced by the “resistant hepatocyte” model system. Cancer Res. 1991;51(4):1308–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.HIXSON DC, ALLISON JP. Monoclonal antibodies recognizing oval cells induced in the liver of rats by N-2-fluorenylacetamide or ethionine in a choline-deficient diet. Cancer Res. 1985;45(8):3750–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.ZHANG M, THORGEIRSSON SS. Modulation of connexins during differentiation of oval cells into hepatocytes. Exp Cell Res. 1994;213(1):37–42. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.YOVCHEV MI, GROZDANOV PN, JOSEPH B, GUPTA S, DABEVA MD. Novel hepatic progenitor cell surface markers in the adult rat liver. Hepatology. 2007;45(1):139–49. doi: 10.1002/hep.21448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.BISGAARD HC, HOLMSKOV U, SANTONI-RUGIU E, et al. Heterogeneity of ductular reactions in adult rat and human liver revealed by novel expression of deleted in malignant brain tumor 1. Am J Pathol. 2002;161(4):1187–98. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64395-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.OMORI N, OMORI M, EVARTS RP, et al. Partial cloning of rat CD34 cDNA and expression during stem cell-dependent liver regeneration in the adult rat. Hepatology. 1997;26(3):720–7. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.OMORI M, OMORI N, EVARTS RP, TERAMOTO T, THORGEIRSSON SS. Coexpression of flt-3 ligand/flt-3 and SCF/c-kit signal transduction system in bile-duct-ligated SI and W mice. Am J Pathol. 1997;150(4):1179–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.VILLANO G, TURATO C, QUARTA S, et al. Hepatic progenitor cells express SerpinB3. BMC Cell Biol. 2014;15:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-15-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.SHIN S, WALTON G, AOKI R, et al. Foxl1-Cre-marked adult hepatic progenitors have clonogenic and bilineage differentiation potential. Genes Dev. 2011;25(11):1185–92. doi: 10.1101/gad.2027811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.MAVIER P, MARTIN N, COUCHIE D, PREAUX AM, LAPERCHE Y, ZAFRANI ES. Expression of stromal cell-derived factor-1 and of its receptor CXCR4 in liver regeneration from oval cells in rat. Am J Pathol. 2004;165(6):1969–77. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63248-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.GERMAIN L, BLOUIN MJ, MARCEAU N. Biliary epithelial and hepatocytic cell lineage relationships in embryonic rat liver as determined by the differential expression of cytokeratins, alpha-fetoprotein, albumin, and cell surface-exposed components. Cancer Res. 1988;48(17):4909–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.TIAN YW, SMITH PG, YEOH GC. The oval-shaped cell as a candidate for a liver stem cell in embryonic, neonatal and precancerous liver: identification based on morphology and immunohistochemical staining for albumin and pyruvate kinase isoenzyme expression. Histochem Cell Biol. 1997;107(3):243–50. doi: 10.1007/s004180050109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.LIBBRECHT L, DESMET V, VAN DAMME B, ROSKAMS T. The immunohistochemical phenotype of dysplastic foci in human liver: correlation with putative progenitor cells. J Hepatol. 2000;33(1):76–84. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80162-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.GAULDIE J, LAMONTAGNE L, HORSEWOOD P, JENKINS E. Immunohistochemical localization of alpha 1-antitrypsin in normal mouse liver and pancreas. Am J Pathol. 1980;101(3):723–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.NAGY P, BISGAARD HC, THORGEIRSSON SS. Expression of hepatic transcription factors during liver development and oval cell differentiation. J Cell Biol. 1994;126(1):223–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.1.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.TANIMIZU N, TSUJIMURA T, TAKAHIDE K, KODAMA T, NAKAMURA K, MIYAJIMA A. Expression of Dlk/Pref-1 defines a subpopulation in the oval cell compartment of rat liver. Gene Expr Patterns. 2004;5(2):209–18. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.LAMAS E, KAHN A, GUILLOUZO A. Detection of mRNAs present at low concentrations in rat liver by in situ hybridization: application to the study of metabolic regulation and azo dye hepatocarcinogenesis. J Histochem Cytochem. 1987;35(5):559–63. doi: 10.1177/35.5.3104450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.SKALA H, VIBERT M, LAMAS E, MAIRE P, SCHWEIGHOFFER F, KAHN A. Molecular cloning and expression of rat aldolase C messenger RNA during development and hepatocarcinogenesis. Eur J Biochem. 1987;163(3):513–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb10898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.HU Z, EVARTS RP, FUJIO K, et al. Expression of transforming growth factor alpha/epidermal growth factor receptor, hepatocyte growth factor/c-met and acidic fibroblast growth factor/fibroblast growth factor receptors during hepatocarcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17(5):931–8. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.5.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.KON J, OOE H, OSHIMA H, KIKKAWA Y, MITAKA T. Expression of CD44 in rat hepatic progenitor cells. J Hepatol. 2006;45(1):90–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.CARDINALE V, WANG Y, CARPINO G, et al. The biliary tree--a reservoir of multipotent stem cells. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9(4):231–40. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.GROZDANOV PN, YOVCHEV MI, DABEVA MD. The oncofetal protein glypican-3 is a novel marker of hepatic progenitor/oval cells. Lab Invest. 2006;86(12):1272–84. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.TSUCHIYA A, HEIKE T, BABA S, et al. Sca-1+ endothelial cells (SPECs) reside in the portal area of the liver and contribute to rapid recovery from acute liver disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;365(3):595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.HATCH HM, ZHENG D, JORGENSEN ML, PETERSEN BE. SDF-1alpha/CXCR4: a mechanism for hepatic oval cell activation and bone marrow stem cell recruitment to the injured liver of rats. Cloning Stem Cells. 2002;4(4):339–51. doi: 10.1089/153623002321025014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.DUDAS J, PAPOUTSI M, HECHT M, et al. The homeobox transcription factor Prox1 is highly conserved in embryonic hepatoblasts and in adult and transformed hepatocytes, but is absent from bile duct epithelium. Anat Embryol (Berl) 2004;208(5):359–66. doi: 10.1007/s00429-004-0403-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.ISHIKAWA T, TERAI S, URATA Y, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 2 facilitates the differentiation of transplanted bone marrow cells into hepatocytes. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;323(2):221–31. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-0077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.HIXSON DC, CHAPMAN L, MCBRIDE A, FARIS R, YANG L. Antigenic phenotypes common to rat oval cells, primary hepatocellular carcinomas and developing bile ducts. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18(6):1169–75. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.6.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.WATANABE T, NAKAGAWA K, OHATA S, et al. SEK1/MKK4-mediated SAPK/JNK signaling participates in embryonic hepatoblast proliferation via a pathway different from NF-kappaB-induced anti-apoptosis. Dev Biol. 2002;250(2):332–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.TANIMIZU N, MIYAJIMA A. Notch signaling controls hepatoblast differentiation by altering the expression of liver-enriched transcription factors. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 15):3165–74. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.HUCH M, DORRELL C, BOJ SF, et al. In vitro expansion of single Lgr5+ liver stem cells induced by Wnt-driven regeneration. Nature. 2013;494(7436):247–50. doi: 10.1038/nature11826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.OMORI N, EVARTS RP, OMORI M, HU Z, MARSDEN ER, THORGEIRSSON SS. Expression of leukemia inhibitory factor and its receptor during liver regeneration in the adult rat. Lab Invest. 1996;75(1):15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.ECKERT C, KIM YO, JULICH H, et al. Podoplanin discriminates distinct stromal cell populations and a novel progenitor subset in the liver. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2016;310(1):G1–12. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00344.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.JIA SQ, REN JJ, DONG PD, MENG XK. Probing the hepatic progenitor cell in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:145253. doi: 10.1155/2013/145253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.SCHMELZER E, WAUTHIER E, REID LM. The phenotypes of pluripotent human hepatic progenitors. Stem Cells. 2006;24(8):1852–8. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.STAMP L, CROSBY HA, HAWES SM, STRAIN AJ, PERA MF. A novel cell-surface marker found on human embryonic hepatoblasts and a subpopulation of hepatic biliary epithelial cells. Stem Cells. 2005;23(1):103–12. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.YU Y, FLINT A, DVORIN EL, BISCHOFF J. AC133–2, a novel isoform of human AC133 stem cell antigen. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(23):20711–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202349200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.RODERFEID M, WEISKIRCHEV R, WAGNER S, et al. Inhibition of hepatic fibrogenesis by matrix metalloproteinase-9 mutants in mice. FASEB J. 2006;20:444–454. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4828com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.PELLICORO A, RAMACHANDRAN P, IREDALE JP, FALLOWFIELD JA. Liver fibrosis and repair: immunne regulation of wound healing in a solid organ. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(3):181–94. doi: 10.1038/nri3623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]