Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is an infrequent cancer with a high disease related mortality rate, even in the context of early stage disease. Until recently, the rate of death from pancreatic cancer has remained largely similar whereby gemcitabine monotherapy was the mainstay of systemic treatment for most stages of disease. With the discovery of active multi-agent chemotherapy regimens, namely FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel, the treatment landscape of pancreatic cancer is slowly evolving. FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel are now considered standard first line treatment options in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Studies are ongoing to investigate the utility of these same regimens in the adjuvant setting. The potential of these treatments to downstage disease is also being actively examined in the locally advanced context since neoadjuvant approaches may improve resection rates and surgical outcomes. As more emerging data become available, the management of pancreatic cancer is anticipated to change significantly in the coming years.

Keywords: Cancer, Neoplasm, Pancreas, Adjuvant treatment, Systemic treatment, Gemcitabine, FOLFIRINOX, Nab-paclitaxel

Core tip: Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is an infrequent cancer with high disease mortality. The focus on management of the disease has been mainly palliation for the past decade. Recently, the discovery of active multi-agent chemotherapies such as FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel has changed the management of the disease. In our current review, we will highlight some of the advances, particularly with respect to systemic therapy options, in the management of different stages of pancreatic cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer is an uncommon cancer with 85% of cases being adenocarcinomas arising from the ductal epithelium and the remainder originating from endocrine islet cells. The estimated incidence of pancreatic cancer is 53070 cases per year in the United States[1]. The incidence has been increasing slowly, at an average of 0.6% per year over the past decade[1,2]. Mortality from pancreatic cancer is high, with a 5-year survival rate of only 8% in all patients, irrespective of stage[1,2]. Pancreatic cancer is more common in the Western world. Globally, it is the seventh leading cause of death[3]. Until 2004, mortality from pancreatic cancer has remained unchanged, indicating a significant need for novel advances in both detection and treatment of this disease.

Surgical resection is the only potentially curative treatment for pancreatic cancer. However, only about 20% of patients present at a point in time when the disease is still considered resectable. Advances in imaging techniques such as endoscopic ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography can better help identify patients who can be managed possibly with surgery. Improvements in surgical techniques as well as a trend for centralization of care to highly specialized surgical centers have also increased the scope of what is defined as surgically resectable[4]. Unfortunately, the 5-year survival rate even among patients with an R0 resection remains poor at about 20%. In the past several years, the discovery of new active systemic therapeutic agents against pancreatic cancer has changed the outlook and paradigm of pancreatic cancer management. While the focus of treatment in the past has been mainly palliation and symptom control, new approaches may now offer survival benefits for patients with either early or advanced pancreatic cancer. In the current review article, we will highlight some of these advances, particularly with respect to systemic therapy options, in the management of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

EARLY STAGE PANCREATIC CANCER

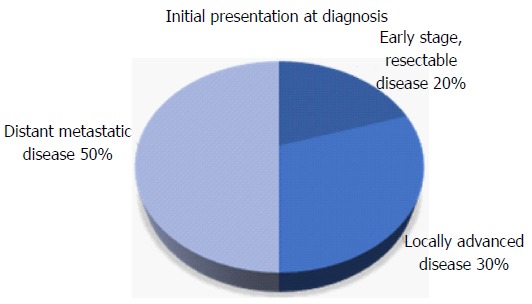

Early stage pancreatic cancer with disease localized to the primary site is uncommon at diagnosis (Figure 1)[5]. The difficulty in early detection is due in part to the challenges associated with identifying high risk groups and a lack of effective screening strategies. Pancreatic cancer is only weakly associated with risk factors such as chronic pancreatitis[6-8], diabetes mellitus[9-11], obesity[12,13], smoking[14,15] and specific genetic syndromes[16,17].

Figure 1.

Distribution of stage at time of diagnosis of pancreatic cancer.

ADJUVANT SYSTEMIC THERAPY

For patients who present sufficiently early to be candidates for surgery, several large randomised trials have demonstrated that adjuvant chemotherapy significantly improves survival outcomes after macroscopic resection of pancreatic cancer. A recent meta-analysis that included ten different studies concluded that adjuvant chemotherapy with 5-flurouracil (5-FU)/leucovorin (LV) or gemcitabine after resection of pancreatic cancer reduces mortality[18].

Fluropyrimidine-based regimens were among the first to show activity in the adjuvant setting. In 1993, the combination of 5-FU plus doxorubicin plus mitomycin C in patients with resected pancreatic or ampullary cancers were observed to improve median overall survival (OS) but not 5-year survival rates[19]. In the ESPAC-1 study, LV modulated 5-FU adjuvant treatment improved the median overall survival from 14.0 to 19.7 mo (Table 1)[20]. The 5-year survival benefit persisted in the chemotherapy group in an updated follow up analysis[20,21]. It is important to note that the benefit of chemotherapy in the ESPAC-1 trial may be underestimated since a proportion of patients also received chemoradiation, which has since been shown to pose a detrimental effect on outcomes in this particular trial. As such, a combined analysis of the ESPAC-1 and ESPAC-3 studies was conducted on patients receiving adjuvant 5-FU/LV alone compared to observation[20-23]. The results confirmed a statistically significant benefit from receiving 5-FU/LV, with a pooled HR of 0.70[20-23].

Table 1.

Summary of adjuvant studies for early stage pancreatic cancer

| Adjuvant systemic therapy | |||||||||

| Study[20,22-24,26,27,29] | Treatment | Treatment group | Control group | ||||||

| DFS (mo) | OS (mo) | 2 yr survival | 5 yr survival | DFS (mo) | OS (mo) | 2 yr survival | 5 yr survival | ||

| 5-FU based treatments | |||||||||

| ESPAC-1 Neoptolemos et al[20], 2001 | 5-FU/LV vs observation | - | 19.7 | - | - | - | 14.0 | - | - |

| ESPAC-1 and 3 pooled analysis Neoptolemos et al[22], 2009 | 5-FU/LV vs observation | - | 23.2 | 49.0% | 24.0% | - | 16.8 | 37.0% | 14.0% |

| Gemcitabine based treatments | |||||||||

| CONKO-001, Oettle et al[24], 2007 | Gemcitabine vs observation | 13.4 | 22.1 | - | 16.5% | 6.9 | 20.5 | - | 5.5% |

| JSAP-02, Ueno et al[26], 2009 | Gemcitabine vs observation | 11.4 | 22.3 | 48.3% | 23.9% | 5.0 | 18.4 | 40.0% | 10.6% |

| Gemcitabine compared to 5-FU | |||||||||

| ESPAC-3, Neoptolemos et al[23], 2010 | Gemcitabine vs 5-FU/LV | 14.3 | 23.6 | 29.6% | - | 14.1 | 23.0 | 30.7% | - |

| RTOG 97-04, Regine et al[27], 2008 | Gemcitabine vs 5-FU/LV in patients receiving CRT | - | 20.5 | - | - | - | 16.9 | - | - |

| Combination treatments | |||||||||

| ESPAC-4, Neoptolemos et al[29], 2017 | Gemcitabine plus capecitabine vs Gemcitabine | 13.9 | 28.0 | 53.8% | - | 13.1 | 25.5 | 52.1% | - |

5-FU: 5-flurouracil; LV: Leucovorin; DFS: Disease free survival; OS: Overall survival.

Gemcitabine is another agent that improves overall survival in early pancreatic cancer. In the CONKO-001 trial conducted in Germany and Austria, 6 cycles of gemcitabine given weekly compared to observation alone resulted in an improvement in disease free survival (DFS) from 6.9 to 13.4 m[24]. An updated analysis of the CONKO-001 study confirmed that the improvement persisted at 5 and 10-years (20.7% vs 10.4% and 12.2% vs 7.7% respectively)[25]. The JSAP-02 study was performed around the same time. Unlike the CONKO-001, investigators examined three cycles of adjuvant gemcitabine compared to observation in a Japanese population with resected pancreatic cancer[26]. This study revealed an improvement in DFS (11.4 mo vs 5.0 mo), thus providing further evidence for the activity of gemcitabine in this patient population[26].

The activity of 5-FU/LV has been compared directly to gemcitabine in the ESPAC-3 trial[23]. It was originally designed as a 3-arm study with a control group, which was subsequently discontinued when evidence showing the benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy became available. This study demonstrated that the median OS for patients treated with 5-FU/LV was 23.0 mo compared to 23.6 mo in patients treated with gemcitabine[23]. Patients given gemcitabine had more hematologic adverse events but treatment was generally better tolerated with significantly less grade 3 or 4 toxicities[23]. The RTOG-9704 study was designed to compare 5-FU/LV and gemcitabine given before and after receiving concurrent chemoradiotherapy with 5-FU[27]. There were no differences in OS between the two groups[27]. Grade 4 hematologic adverse effects were significantly worse in the gemcitabine arm of this study, which could be explained by the radiosensitizing effects of gemcitabine. A meta-analysis performed by Yu et al[28], which included four of the largest randomized adjuvant pancreatic studies (ESPAC-3, RTOG 9704, CONKO-001 and JSAP-02), found that gemcitabine improved overall survival over the comparator arm of either observation or 5-FU/LV, with a HR 0.88. More importantly, further sensitivity analysis in this meta-analysis indicated that the results remained unchanged even when any one of the studies were removed, thereby providing evidence that the survival improvement was not driven by the placebo arm alone[28]. In clinical practice, gemcitabine monotherapy is often preferred due to ease of administration and tolerability.

Because adjuvant chemotherapy offers benefits to some patients, there have been efforts to determine if intensification of the regimens can increase their effectiveness. The recently published ESPAC-4 study compared a combination of gemcitabine plus capecitabine over gemcitabine alone[29]. A larger number of patients included in this study had evidence of nodal disease or locally advanced disease that was deemed upfront resectable. The primary endpoint of OS was significantly improved in the combination group with a median OS of 28.0 mo compared to 25.5 mo in the monotherapy group. Interestingly, there was no difference in the relapse free survival between the two groups. Grade 3-4 adverse events of diarrhea, neutropenia and hand foot syndrome were more common in the gemcitabine plus capecitabine group. However, overall quality of life measures were similar between the two groups. Given the tolerability of gemcitabine plus capecitabine and the demonstrated benefits in survival, combination adjuvant therapy is now considered the standard in clinical settings. Clinical studies are currently underway to examine if there are additional benefits to further treatment intensification. Marsh et al[30] published preliminary findings of a pilot study where twenty-one patients with early stage pancreatic cancer were given four cycles of modified FOLFIRINOX before and after surgery and found a median OS of 33.4 mo. To this end, regimens such a gemcitabine plus nanoparticle albumin bound paclitaxel (nab-paclitaxel) and a combination of 5-FU, irinotecan and oxaliplatin (FOLFIRINOX) are actively being evaluated in the adjuvant setting.

The ESPAC-4 study also highlights some the challenges with adjuvant systemic treatment in pancreatic cancer patients. Despite most patients having a good performance status at the time of randomization, only 54% and 65% of patients were able to complete all planned cycles of treatment in the gemcitabine plus capecitabine and gemcitabine groups respectively. A neoadjuvant approach with chemotherapy delivered prior to patients undergoing a major operation may improve rates of systemic treatment completion. Some groups also believe that earlier chemotherapy is important to eradicate micrometastatic disease. The SWOG group is currently recruiting patients with resectable disease to six cycles of neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX or nine cycles of gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel followed by surgical resection[31].

ADJUVANT CHEMORADIOTHERAPY

While the benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy are widely accepted and broadly used in clinical practice, the role of adjuvant chemoradiotherapy is more controversial. Prospective evidence regarding the value of chemoradiotherapy is frequently older and underpowered. The GITSG study published in 1985 was one of the first large studies to suggest a benefit of adding radiation to chemotherapy[32]. Forty-nine patients were randomized to observation alone or split course radiotherapy to a total of 40 Gy plus concurrent 5-FU. Although median OS was reported to be longer in the chemoradiotherapy group (20 mo vs 11 mo), this study was closed early due to poor accrual and was considered underpowered[32]. An updated analysis which included an additional 30 randomized patients revealed similar results[33]. The authors concluded that there was a significant survival advantage with the use of adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. As there were some smaller studies with conflicting results published at the same time, the EORTC GI cooperative group pursued another trial with a similar design as the GITSG trial across multiple centers in Europe. Patients were randomized to observation or to the same split course radiotherapy plus infusional 5-FU[34]. However, the benefit of chemoradiotherapy seen in this later study was much smaller and only borderline significant[34]. In contrast, these authors concluded that there was insufficient evidence to recommend the routine use of chemoradiation after resection of pancreatic cancer[34]. Long term follow up of these patient did not identify any differences in outcomes over time[35].

The ESPAC-1 study examined the effect of chemoradiation compared to chemotherapy alone vs observation and concluded that the chemoradiation group had a trend towards worse OS[20,21]. A meta-analysis performed by Liao et al[18] supported the observation that chemoradiation is less effective than chemotherapy alone. However, the results of this meta-analysis were likely driven by the patients in the ESPAC-1 study. Flaws in the study design of the ESPAC-1 trial, including a pooled analysis of its three different sub-studies, continue to be a major source of controversy. In clinical practice, the patterns of use of chemoradiotherapy differ significantly among clinicians and across cancer centers.

The uncertainty regarding the utility of adjuvant chemoradiotherapy is ongoing. Several contemporary retrospective studies suggest that there is a survival benefit[36-39]. Rutter et al[36] reviewed the national cancer database in the United States and identified 6165 patients from 1998 to 2009 who were treated with adjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy. The mean radiotherapy dose received was 50.4 Gy, which was higher than the doses used in older prospective studies. They found that chemoradiotherapy was associated with an improved overall survival over chemotherapy alone with an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.89. Although retrospective analyses have their limitations, it is difficult to discount several large population-based studies that suggest a possible survival improvement with chemoradiotherapy. Changes in surgical and modern radiotherapy planning techniques may account for differences in survival over time. New prospective randomized studies that incorporate the use of modern radiation techniques and current chemotherapy regimens are still needed to determine whether adjuvant chemoradiotherapy is actually beneficial.

LOCALLY ADVANCED PANCREATIC CANCER

About 30% of patients present with non-metastatic locally advanced disease[40]. This cohort represents a heterogeneous group of patients whose management differs depending on surgical resectability. Prior to the advent of active systemic therapies, locally advanced tumors were most commonly managed akin to advanced metastatic disease. Gemcitabine, an agent that has been considered the standard of care in distant advanced disease for years, is also used for locally advanced pancreatic cancer[41]. One phase II study performed among locally advanced patients reported a median OS of 15 mo[42]. Use of multiagent chemotherapy, such as FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine in combination with other cytotoxic agents, is increasingly common in the first line setting for locally advanced disease albeit there is little prospective evidence. A recent small phase II study along with other observational studies indicate that FOLFIRINOX has a survival benefit in locally advanced disease when compared to historical controls[43-45]. A systematic review of studies involving first line FOLFIRNOX in locally pancreatic cancer reported a median overall survival of 24.2 mo[46].

The use of more active systemic treatments has also created the potential that some tumors may be sufficiently downstaged to become resectable. The definitions of locally advanced unresectable disease or borderline resectable disease continue to be vague and highly dependent on surgical expertise and discretion. There is generally a lack of prospective randomized data in this area. Induction chemotherapy is occasionally used in clinical practice and recommended by some consensus-driven guidelines[47,48]. There are several options for systemic therapy with no single regimen being considered the standard. Use of FOLFIRINOX as neoadjuvant therapy is of particular interest given its response rate of 32% in advanced disease[49]. Multiple observational analyses on neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX have been published with encouraging results that show FOLFIRINOX improves R0 resection rates to up to 70% in some studies[50-52]. At the current time, there are few published studies examining the use of gemcitabine doublets as neoadjuvant therapy for locally advanced disease. A number of small studies focusing on the neoadjuvant combination of gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin showed that the regimen is feasible, with reports that up to 40%-60% of patients eventually proceed onto surgery[53,54]. Gemcitabine in combination with capecitabine or docetaxel have also been described as feasible and potentially effective as neoadjuvant therapy for locally advanced disease[55,56]. There is interest in investigating the combination of gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel as neoadjuvant treatment given its efficacy in metastatic disease. Early results from observational cohorts suggest a favorable response rate when gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel was used as induction treatment[57,58].

In contrast to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the use of concurrent chemoradiotherapy has not been shown to improve survival. The LAP-07 study randomized patients with locally advanced disease to gemcitabine with or without erlotinib for four cycles followed by a second randomization to further chemotherapy or chemoradiation[59]. Unfortunately, the study was stopped early due to futility. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy did not show any survival benefits over chemotherapy alone. It is still unclear whether the addition of radiotherapy improves surgical outcomes. Thus, there is continued interest in studying whether radiotherapy after multi-agent induction chemotherapy would improve the rates of R0 resection[60-62]. Katz et al[60] investigated the combination of modified FOLFIRINOX for 4 cycles followed by concurrent chemoradiation with capecitabine in 22 patients with borderline resectable disease and reported that 60% of patients received a surgical resection with 93% of those achieving an R0 resection.

ADVANCED PANCREATIC CANCER

More than 50% of patients present with advanced stage disease and experience a dismal prognosis. Patients with locally advanced unresectable disease and distant metastatic disease are frequently treated in a similar fashion. Until recently, single agent chemotherapy was the mainstay of treatment offering only a very modest benefit in survival. Newer approaches with combination chemotherapy have finally shown an improvement in survival when compared to monotherapy.

Before the introduction of combination treatment, gemcitabine monotherapy was the cornerstone of treatment. At present, it remains the standard first line option for patients with poor performance status who are unable to tolerate combination chemotherapy. In 1997, a phase III trial was published which compared gemcitabine to 5-FU, the latter of which was the standard therapy based on studies in the 1950-1960s with highly variable results (Table 2)[41]. The primary endpoint of the trial was clinical benefit, defined as a sustained improvement in symptoms related to pancreatic cancer, which was significantly better in the gemcitabine arm. Secondary endpoints of survival were also improved with median OS of 5.7 mo in the gemcitabine group compared to 4.4 mo in the 5-FU group. Based on results of this trial, gemcitabine became the standard of care for advanced disease for the subsequent 20 years.

Table 2.

Summary of first line studies for advanced pancreatic cancer

| First line treatment for metastatic disease | |||||||||

| Study[41,49,63-67,71] | Treatment | Treatment group | Control group | ||||||

| ORR | PFS (mo) | OS (mo) | 1 yr Survival | ORR | PFS (mo) | OS (mo) | 1 yr Survival | ||

| Standard of care | |||||||||

| Burris et al[41], 1997 | Gemcitabine vs 5-FU/LV | - | 9 wk | 5.65 | 18.0% | - | 4 wk | 4.01 | 2.0% |

| Conroy et al[49], 2011 | FOLFIRINOX vs Gemcitabine | 31.6% | 6.4 | 11.1 | 48.4% | 9.4% | 3.3 | 6.8 | 20.6% |

| Von Hoff et al[71], 2013 | Nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine vs gemcitabine | 23.0% | 5.5 | 8.5 | 35.0% | 7.0% | 3.7 | 6.7 | 22.0% |

| Gemcitabine doublets | |||||||||

| Berlin et al[63], 2002 | Gemcitabine plus 5-FU vs gemcitabine | 6.9% | 3.4 | 6.7 | - | 5.6% | 2.2 | 5.4 | - |

| Herrmann et al[64], 2007 | Gemcitabine plus capecitabine vs gemcitabine | 10.0% | 4.3 | 8.4 | 32.0% | 7.8% | 3.9 | 7.2 | 30.0% |

| Moore et al[66], 2007 | Gemcitabine plus erlotinib vs gemcitabine | 8.6% | 3.8 | 6.2 | 23.0% | 8.0% | 3.6 | 5.9 | 17.0% |

| Philip et al[67], 2010 | Gemcitabine plus cetuximab vs gemcitabine | 12.0% | 3.4 | 6.3 | - | 14.0% | 3.0 | 5.9 | - |

| Ueno et al[65], 2013 | Gemcitabine plus S1 vs gemcitabine | 29.3% | 5.7 | 10.1 | 40.7% | 13.3% | 4.1 | 8.8 | 35.4% |

5-FU: 5-flurouracil; LV: Leucovorin; DFS: Disease free survival; OS: Overall survival; ORR: Overall response rate.

There were multiple attempts to combine gemcitabine with other agents to improve survival. Studies involving gemcitabine plus 5-FU, capecitabine, and S1 uniformly failed to demonstrate benefit over gemcitabine alone[63-65]. Results of gemcitabine in combination with newer agents targeting the EGFR or VEGF pathway were also disappointing. A phase III study combining gemcitabine plus erlotinib did show a modest improvement in survival by 2 wk[66]. However, this regimen has not been widely accepted into clinical practice because the magnitude of benefit was marginal. Furthermore, a study using a combination of gemcitabine and cetuximab, a monoclonal antibody against EGFR, failed to demonstrate any benefit over gemcitabine alone[67]. Likewise, gemcitabine plus bevacizumab in a phase III study also failed to show a survival benefit over gemcitabine alone[68].

Because treatment results from initial gemcitabine doublets were generally disappointing, investigations into other active agents were made. Agents such as 5-FU, irinotecan and oxaliplatin have shown activity in pancreatic cancer and a combination of these three were shown to be safe in phase I studies[69]. As such, a phase II/III trial was conducted to study the effects of FOLFIRINOX compared to standard gemcitabine monotherapy[49]. Surprisingly, the results demonstrated a significant overall survival advantage of 11.0 mo compared to 6.8 mo in the gemcitabine group. Quality of life measured at 6 mo was also significantly better in the FOLFIRINOX group, likely secondary to better disease control. However, toxicity is greater in the FOLFIRNOX group and patients included in the study were required to have a baseline ECOG performance of 0-1. FOLFIRINOX is now considered a first line option in patients with unresectable or advanced pancreatic cancer with a good performance status.

In contrast to other gemcitabine doublets, a recent study demonstrated a clinically significant antitumor effect when gemcitabine was combined with nab-paclitaxel. Molecular profiling of pancreatic cancer show that the tumor often overexpresses an albumin-binding protein suggesting that this formulation may increase the intratumoral concentrations of gemcitabine[70]. The phase III data published in 2013 described that the combination of nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine was superior to gemcitabine alone with a median OS of 8.5 mo vs 6.7 mo[71]. The superiority in survival persisted with long term follow up at 3 years[72]. The combination of gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel has also been recently approved for first line treatment of advanced pancreatic cancer.

There are currently no studies that directly compare the activity of FOLFIRINOX to gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel and both are approved for use in the first line setting. In clinical practice, the choice of regimen is often dependent on the toxicity profiles. FOLFIRINOX has more toxicities and is usually reserved for patients with good performance status. Gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel has been studied in patients with a KPS ≥ 70, which approximates ECOG 2. Population based studies revealed that few real world patients actually meet the eligibility criteria used in the clinical trials with only about 25% of patients able to receive FOLFIRINOX and 45% able to receive gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel[73,74]. In patients with borderline performance who may not be able to tolerate combination cytotoxic therapy, gemcitabine monotherapy remains an option. Unfortunately, there are limited data from large prospective randomized data investigating second line therapies upon progression. With the use of more active first line treatments, patients are now faring better to the degree that warrants consideration of second line therapy. Nonetheless, second line treatment represents an area of clinical unmet need. Systemic therapy is still often used for patients with good performance status who wishes to receive treatment. Agents that are considered active in pancreatic cancer such as 5-FU, oxaliplatin, irinotecan and gemcitabine are reasonable to be used in the second line setting with no single regimen that can be currently considered as the standard of care. Retrospective studies suggest that use of second line therapies is feasible with a potential survival benefit[75]. Patients enrolled into the MPACT study were followed prospectively and results were published on the outcomes of second line therapy[76]. The authors reported a significant benefit to receiving any second line therapy with an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.47[76]. However, the total number of patients was small and results may be confounded. The combination of 5-FU/LV and oxaliplatin has been studied in two phase III trials with conflicting results. The German CONKO study group conducted a trial comparing FF (weekly infusional 5-FU and folinic acid) to OFF (oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2 on days 8 and 22 plus FF followed by a 2 wk break) in patients who progressed after first line gemcitabine monotherapy[77,78]. A significant benefit was seen in the OFF group with a median OS of 5.9 mo compared to 3.3 mo[77,78]. The PANCREOX study performed by the Canadian group compared second line biweekly bolus plus infusional 5-FU/LV to mFOLFOX6 (biweekly bolus plus infusional 5-FU/LV plus oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2). Contrary to the findings in the German study, patients receiving mFOLFOX6 suffered an inferior survival with more toxicity compared to 5-FU/LV alone (6.1 mo vs 9.9 mo)[79]. Conflicting results of the two studies may be explained by differences in the inclusion criteria and treatment regimens. The NAPOLI-1 study is a phase III trial investigating the use of nanoliposomal irinotecan with or without 5-FU/LV compared to 5-FU/LV alone in heavily pretreated patients[80]. The study demonstrated a median OS of 6.1 mo in patients who received nanoliposomal irinotecan plus 5-FU/LV compared to 4.2 mo in patients receiving 5-FU/LV alone. This combination may become the standard second line treatment in the future.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The outcomes of pancreatic cancer remain poor despite recent advances. Therefore, research into novel and different ways of targeting this tumor is still ongoing.

One of the reasons why pancreatic cancer is so difficult to treat with conventional cytotoxic therapy is thought to be related to the desmoplastic response in tumor stroma, which promotes tumor growth and compromises chemotherapy delivery[81-83]. The JAK/STAT signalling transduction pathway mediates the tumor and host inflammatory response. Ruxolitinib, a JAK inhibitor, in combination with capecitabine has demonstrated efficacy in patients who progressed after gemcitabine in a phase II study[84]. The intense stromal reaction is also often associated with tissue hypoxia. Evofosfamide, a prodrug activated under hypoxic conditions could increase drug delivery to the tumor. Unfortunately, the phase III results did not show a survival benefit[85]. Pancreatic cancer stroma has also been shown to accumulate hyaluronan and a novel approach using a recombinant human hyaluronidase together with gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel has shown promising preliminary results, specifically improving response rates and progression free survival in the phase II setting[86]. Ibrutinib, an agent commonly used in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia is thought to inhibit mast cell degranulation in the stroma and subsequent angiogenesis and collagen deposition. This agent is also being investigated[87].

Molecular profiling may further help us gain a better understanding of the molecular pathways in pancreatic cancer[88,89]. While mutations in KRAS, TP53 and CDKN2A are common in pancreatic cancer, they have proven to be challenging to target. However, there is mounting evidence of genomic alterations in TGF-β signaling and studies investigating the utility of TGF-β inhibitors are actively underway[90].

The identification of specific subtypes of pancreatic cancers or special patient populations based on molecular profiles is a significant area of interest. For example, the presence of microsatellite instability may predict response to immunotherapy even though it has not been shown to be a very active type of treatment in an unselected population of pancreatic cancer. A special group of patients are those with mutations in BRCA-1/2. Emerging data from other cancer sites associated with BRCA mutations such as breast and ovarian cancer suggest hypersensitivity to platinum agents[91-95]. Oxaliplatin has already demonstrated activity in pancreatic cancer[49], but it is unknown if BRCA mutated patients will demonstrate a superior response compared to an unselected population. PARP inhibitors have been shown to improve treatments outcomes in BRCA mutated ovarian cancer. A germline mutation in BRCA-2 is known to be correlated with the development of pancreatic cancer, but the prevalence is unknown. It has been reported that up to 5%-9% of pancreatic cancer patients harbor the mutation[96,97]. Studies of PARP inhibitors in BRCA mutated pancreatic cancer patients are in development with some early data indicating promising efficacy[97,98].

CONCLUSION

Pancreatic cancer is a systemic disease since even the majority of patients with early disease eventually develop metastases. While gemcitabine poses some anti-tumor activity and improves survival in the adjuvant setting, the focus of management for most patients with pancreatic cancer has, to date, been palliative. The discovery of active multi-agent chemotherapy regimens such as FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel has changed the recent landscape in the management of this disease in many aspects. In early stage disease, multi-agent chemotherapies are being investigated for their potential benefit in overall survival. The PRODIGE and APACT studies are ongoing and hopefully will provide us with new data in the next several years. The potential for multi-agent chemotherapy to downstage locally advanced disease to improve resection rates is a significant area of interest. In fit patients with metastatic disease who can tolerate combination treatment, FOLFIRINOX as well as gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel are considered standards of care. Advances in molecular profiling and gene sequencing will likely help us better understand the biology of pancreatic cancer. Novel targets for drug development as well as new methods of drug delivery are areas of active clinical research. Finally, identification of specific subgroups of patients such as BRCA mutation carriers may also allow clinicians to better individualize care for future patients.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: Authors declare no conflict of interests for this article.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Canada

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: February 12, 2017

First decision: March 7, 2017

Article in press: April 19, 2017

P- Reviewer: Aglietta M, Lee HC, Li C S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Cancer Society. Global Cancer Facts & Figures. 3rd ed. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gooiker GA, van Gijn W, Wouters MW, Post PN, van de Velde CJ, Tollenaar RA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the volume-outcome relationship in pancreatic surgery. Br J Surg. 2011;98:485–494. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Cancer Institute. Cancer stat facts: cancer of the pancreas. Surveillance: Epidemiology, and End Results Program; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Cavallini G, Ammann RW, Lankisch PG, Andersen JR, Dimagno EP, Andrén-Sandberg A, Domellöf L. Pancreatitis and the risk of pancreatic cancer. International Pancreatitis Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1433–1437. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305203282001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ekbom A, McLaughlin JK, Karlsson BM, Nyrén O, Gridley G, Adami HO, Fraumeni JF. Pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer: a population-based study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:625–627. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.8.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duell EJ, Lucenteforte E, Olson SH, Bracci PM, Li D, Risch HA, Silverman DT, Ji BT, Gallinger S, Holly EA, et al. Pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer risk: a pooled analysis in the International Pancreatic Cancer Case-Control Consortium (PanC4) Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2964–2970. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huxley R, Ansary-Moghaddam A, Berrington de González A, Barzi F, Woodward M. Type-II diabetes and pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis of 36 studies. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:2076–2083. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inoue M, Iwasaki M, Otani T, Sasazuki S, Noda M, Tsugane S. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of cancer: results from a large-scale population-based cohort study in Japan. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1871–1877. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Batabyal P, Vander Hoorn S, Christophi C, Nikfarjam M. Association of diabetes mellitus and pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a meta-analysis of 88 studies. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:2453–2462. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3625-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo J, Margolis KL, Adami HO, LaCroix A, Ye W. Obesity and risk of pancreatic cancer among postmenopausal women: the Women's Health Initiative (United States) Br J Cancer. 2008;99:527–531. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arslan AA, Helzlsouer KJ, Kooperberg C, Shu XO, Steplowski E, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Fuchs CS, Gross MD, Jacobs EJ, Lacroix AZ, et al. Anthropometric measures, body mass index, and pancreatic cancer: a pooled analysis from the Pancreatic Cancer Cohort Consortium (PanScan) Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:791–802. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lynch SM, Vrieling A, Lubin JH, Kraft P, Mendelsohn JB, Hartge P, Canzian F, Steplowski E, Arslan AA, Gross M, et al. Cigarette smoking and pancreatic cancer: a pooled analysis from the pancreatic cancer cohort consortium. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170:403–413. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bosetti C, Lucenteforte E, Silverman DT, Petersen G, Bracci PM, Ji BT, Negri E, Li D, Risch HA, Olson SH, et al. Cigarette smoking and pancreatic cancer: an analysis from the International Pancreatic Cancer Case-Control Consortium (Panc4) Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1880–1888. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson D, Easton DF. Cancer Incidence in BRCA1 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1358–1365. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.18.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Win AK, Young JP, Lindor NM, Tucker KM, Ahnen DJ, Young GP, Buchanan DD, Clendenning M, Giles GG, Winship I, et al. Colorectal and other cancer risks for carriers and noncarriers from families with a DNA mismatch repair gene mutation: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:958–964. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liao WC, Chien KL, Lin YL, Wu MS, Lin JT, Wang HP, Tu YK. Adjuvant treatments for resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1095–1103. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70388-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bakkevold KE, Arnesjø B, Dahl O, Kambestad B. Adjuvant combination chemotherapy (AMF) following radical resection of carcinoma of the pancreas and papilla of Vater--results of a controlled, prospective, randomised multicentre study. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29A:698–703. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(05)80349-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neoptolemos JP, Dunn JA, Stocken DD, Almond J, Link K, Beger H, Bassi C, Falconi M, Pederzoli P, Dervenis C, et al. Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy in resectable pancreatic cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;358:1576–1585. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06651-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Friess H, Bassi C, Dunn JA, Hickey H, Beger H, Fernandez-Cruz L, Dervenis C, Lacaine F, et al. A randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1200–1210. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Tudur Smith C, Bassi C, Ghaneh P, Owen E, Moore M, Padbury R, Doi R, Smith D, et al. Adjuvant 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid vs observation for pancreatic cancer: composite data from the ESPAC-1 and -3(v1) trials. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:246–250. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Bassi C, Ghaneh P, Cunningham D, Goldstein D, Padbury R, Moore MJ, Gallinger S, Mariette C, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus folinic acid vs gemcitabine following pancreatic cancer resection: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1073–1081. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, Gellert K, Langrehr J, Ridwelski K, Schramm H, Fahlke J, Zuelke C, Burkart C, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297:267–277. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oettle H, Neuhaus P, Hochhaus A, Hartmann JT, Gellert K, Ridwelski K, Niedergethmann M, Zülke C, Fahlke J, Arning MB, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and long-term outcomes among patients with resected pancreatic cancer: the CONKO-001 randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310:1473–1481. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.279201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ueno H, Kosuge T, Matsuyama Y, Yamamoto J, Nakao A, Egawa S, Doi R, Monden M, Hatori T, Tanaka M, et al. A randomised phase III trial comparing gemcitabine with surgery-only in patients with resected pancreatic cancer: Japanese Study Group of Adjuvant Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:908–915. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Regine WF, Winter KA, Abrams RA, Safran H, Hoffman JP, Konski A, Benson AB, Macdonald JS, Kudrimoti MR, Fromm ML, et al. Fluorouracil vs gemcitabine chemotherapy before and after fluorouracil-based chemoradiation following resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1019–1026. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.9.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu Z, Zhong W, Tan ZM, Wang LY, Yuan YH. Gemcitabine Adjuvant Therapy for Resected Pancreatic Cancer: A Meta-analysis. Am J Clin Oncol. 2015;38:322–325. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3182a46782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neoptolemos JP, Palmer DH, Ghaneh P, Psarelli EE, Valle JW, Halloran CM, Faluyi O, O'Reilly DA, Cunningham D, Wadsley J, et al. Comparison of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:1011–1024. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32409-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marsh RW, Zhang SQ, Baker M, Catenacci DVT, Kozloff M, Polite BN, Posner MC, Roggin KK, Talamonti MS, Wroblewski K, et al. Peri-operative modified FOLFIRINOX in resectable pancreatic cancer: A pilot study (American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, 2016; 34: suppl: abstr 4103) Available from: http://meeting.ascopubs.org/cgi/content/abstract/34/4_suppl/312.

- 31.Sohal D, McDonough SL, Ahmad SA, Gandhi N, Beg MS, Wang-Gillam A, Guthrie KA, Lowy AM, Philip PA, Hochster HS. SWOG S1505: A randomized phase II study of perioperative mFOLFIRINOX vs gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel as therapy for resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma (American Society of Clinical Oncology, 2016; 34: suppl: abstr TPS4151) Available from: http://meeting.ascopubs.org/cgi/content/abstract/34/15_suppl/TPS4151.

- 32.Kalser MH, Ellenberg SS. Pancreatic cancer. Adjuvant combined radiation and chemotherapy following curative resection. Arch Surg. 1985;120:899–903. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1985.01390320023003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Further evidence of effective adjuvant combined radiation and chemotherapy following curative resection of pancreatic cancer. Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group. Cancer. 1987;59:2006–2010. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870615)59:12<2006::aid-cncr2820591206>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klinkenbijl JH, Jeekel J, Sahmoud T, van Pel R, Couvreur ML, Veenhof CH, Arnaud JP, Gonzalez DG, de Wit LT, Hennipman A, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy and 5-fluorouracil after curative resection of cancer of the pancreas and periampullary region: phase III trial of the EORTC gastrointestinal tract cancer cooperative group. Ann Surg. 1999;230:776–782; discussion 782-784. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199912000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smeenk HG, van Eijck CH, Hop WC, Erdmann J, Tran KC, Debois M, van Cutsem E, van Dekken H, Klinkenbijl JH, Jeekel J. Long-term survival and metastatic pattern of pancreatic and periampullary cancer after adjuvant chemoradiation or observation: long-term results of EORTC trial 40891. Ann Surg. 2007;246:734–740. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318156eef3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rutter CE, Park HS, Corso CD, Lester-Coll NH, Mancini BR, Yeboa DN, Johung KL. Addition of radiotherapy to adjuvant chemotherapy is associated with improved overall survival in resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma: An analysis of the National Cancer Data Base. Cancer. 2015;121:4141–4149. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sugawara A, Kunieda E. Effect of adjuvant radiotherapy on survival in resected pancreatic cancer: a propensity score surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database analysis. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110:960–966. doi: 10.1002/jso.23752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kooby DA, Gillespie TW, Liu Y, Byrd-Sellers J, Landry J, Bian J, Lipscomb J. Impact of adjuvant radiotherapy on survival after pancreatic cancer resection: an appraisal of data from the national cancer data base. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:3634–3642. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3047-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hsu CC, Herman JM, Corsini MM, Winter JM, Callister MD, Haddock MG, Cameron JL, Pawlik TM, Schulick RD, Wolfgang CL, et al. Adjuvant chemoradiation for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: the Johns Hopkins Hospital-Mayo Clinic collaborative study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:981–990. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0743-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Cancer Institute. Cancer of the Pancreas - Cancer Stat Facts. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burris HA, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML, Modiano MR, Cripps MC, Portenoy RK, Storniolo AM, Tarassoff P, et al. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2403–2413. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishii H, Furuse J, Boku N, Okusaka T, Ikeda M, Ohkawa S, Fukutomi A, Hamamoto Y, Nakamura K, Fukuda H. Phase II study of gemcitabine chemotherapy alone for locally advanced pancreatic carcinoma: JCOG0506. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40:573–579. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stein SM, James ES, Deng Y, Cong X, Kortmansky JS, Li J, Staugaard C, Indukala D, Boustani AM, Patel V, et al. Final analysis of a phase II study of modified FOLFIRINOX in locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2016;114:737–743. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marthey L, Sa-Cunha A, Blanc JF, Gauthier M, Cueff A, Francois E, Trouilloud I, Malka D, Bachet JB, Coriat R, et al. FOLFIRINOX for locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: results of an AGEO multicenter prospective observational cohort. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:295–301. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3898-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peddi PF, Lubner S, McWilliams R, Tan BR, Picus J, Sorscher SM, Suresh R, Lockhart AC, Wang J, Menias C, et al. Multi-institutional experience with FOLFIRINOX in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. JOP. 2012;13:497–501. doi: 10.6092/1590-8577/913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suker M, Beumer BR, Sadot E, Marthey L, Faris JE, Mellon EA, El-Rayes BF, Wang-Gillam A, Lacy J, Hosein PJ, et al. FOLFIRINOX for locally advanced pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and patient-level meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:801–810. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)00172-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Balaban EP, Mangu PB, Khorana AA, Shah MA, Mukherjee S, Crane CH, Javle MM, Eads JR, Allen P, Ko AH, et al. Locally Advanced, Unresectable Pancreatic Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2654–2668. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.5561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seufferlein T, Bachet JB, Van Cutsem E, Rougier P. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma: ESMO-ESDO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23 Suppl 7:vii33–vii40. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouché O, Guimbaud R, Bécouarn Y, Adenis A, Raoul JL, Gourgou-Bourgade S, de la Fouchardière C, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817–1825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sadot E, Doussot A, O'Reilly EM, Lowery MA, Goodman KA, Do RK, Tang LH, Gönen M, D'Angelica MI, DeMatteo RP, et al. FOLFIRINOX Induction Therapy for Stage 3 Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:3512–3521. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4647-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rombouts S, Walma M, Vogel JA, Rijssen Lv, Wilmink J, Mohammad NH, Santvoort Hv, Molenaar IQ, Besselink MG. Systematic review of resection rates and clinical outcomes after FOLFIRINOX-based treatment in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer. American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting. 2016;34:suppl: abstr 4115. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5373-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Portales F, Gagniard B, Thezenas S, Samalin E, Assenat E, Alline M, Colombo P, Rouanet P, Carrere S, Quenet F, et al. Feasibility and impact on resectability of FOLFIRINOX in locally-advanced and borderline pancreatic cancer. American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting. 2016;34:suppl: abstr e15708. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim EJ, Ben-Josef E, Herman JM, Bekaii-Saab T, Dawson LA, Griffith KA, Francis IR, Greenson JK, Simeone DM, Lawrence TS, et al. A multi-institutional phase 2 study of neoadjuvant gemcitabine and oxaliplatin with radiation therapy in patients with pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2013;119:2692–2700. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sahora K, Kuehrer I, Eisenhut A, Akan B, Koellblinger C, Goetzinger P, Teleky B, Jakesz R, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Ba'ssalamah A, et al. NeoGemOx: Gemcitabine and oxaliplatin as neoadjuvant treatment for locally advanced, nonmetastasized pancreatic cancer. Surgery. 2011;149:311–320. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee JL, Kim SC, Kim JH, Lee SS, Kim TW, Park DH, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH, Kim JH, et al. Prospective efficacy and safety study of neoadjuvant gemcitabine with capecitabine combination chemotherapy for borderline-resectable or unresectable locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Surgery. 2012;152:851–862. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sahora K, Kuehrer I, Schindl M, Koelblinger C, Goetzinger P, Gnant M. NeoGemTax: gemcitabine and docetaxel as neoadjuvant treatment for locally advanced nonmetastasized pancreatic cancer. World J Surg. 2011;35:1580–1589. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gupta NK, Singh K, Glass T, Davis C, Lybik M, Leagre C, Liebross RH, Dugan T, Edwards M, Givens S, et al. Neoadjuvant gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel followed by concurrent capecitabine and radiation efficacy in borderline resectable (BR) pancreatic cancer. American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting. 2016;34:suppl: abstr e15698. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Laethem JV, Bali MA, Borbath I, Verset G, Demols A, Puleo F, Peeters M, Annet L, Ceratti A, Ghilain A, et al. Preoperative gemcitabine-nab-paclitaxel (G-NP) for (borderline) resectable (BLR) or locally advanced (LA) pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC): feasibility results and early response monitoring by Diffusion-Weighted (DW) MR. American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting. 2016;34:suppl: abstr 4116. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hammel P, Huguet F, van Laethem JL, Goldstein D, Glimelius B, Artru P, Borbath I, Bouché O, Shannon J, André T, et al. Effect of Chemoradiotherapy vs Chemotherapy on Survival in Patients With Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer Controlled After 4 Months of Gemcitabine With or Without Erlotinib: The LAP07 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315:1844–1853. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Katz MH, Shi Q, Ahmad SA, Herman JM, Marsh Rde W, Collisson E, Schwartz L, Frankel W, Martin R, Conway W, et al. Preoperative Modified FOLFIRINOX Treatment Followed by Capecitabine-Based Chemoradiation for Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Cancer: Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology Trial A021101. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:e161137. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kharofa J, Kelly TR, Ritch PS, George B, Wiebe LA, Thomas JP, Christians KK, Evans DB, Erickson B. 5-FU/leucovorin, irinotecan, oxaliplatin (FOLFIRINOX) induction followed by chemoXRT in borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:suppl: abstr e14613. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Berlin JD, Catalano P, Thomas JP, Kugler JW, Haller DG, Benson AB. Phase III study of gemcitabine in combination with fluorouracil versus gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic carcinoma: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial E2297. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3270–3275. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Herrmann R, Bodoky G, Ruhstaller T, Glimelius B, Bajetta E, Schüller J, Saletti P, Bauer J, Figer A, Pestalozzi B, et al. Gemcitabine plus capecitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer: a randomized, multicenter, phase III trial of the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research and the Central European Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2212–2217. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.0886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ueno H, Ioka T, Ikeda M, Ohkawa S, Yanagimoto H, Boku N, Fukutomi A, Sugimori K, Baba H, Yamao K, et al. Randomized phase III study of gemcitabine plus S-1, S-1 alone, or gemcitabine alone in patients with locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer in Japan and Taiwan: GEST study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1640–1648. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.3680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, Figer A, Hecht JR, Gallinger S, Au HJ, Murawa P, Walde D, Wolff RA, et al. Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1960–1966. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Philip PA, Benedetti J, Corless CL, Wong R, O'Reilly EM, Flynn PJ, Rowland KM, Atkins JN, Mirtsching BC, Rivkin SE, et al. Phase III study comparing gemcitabine plus cetuximab versus gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Southwest Oncology Group-directed intergroup trial S0205. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3605–3610. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.7550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kindler HL, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, Sutherland S, Schrag D, Hurwitz H, Innocenti F, Mulcahy MF, O'Reilly E, Wozniak TF, et al. Gemcitabine plus bevacizumab compared with gemcitabine plus placebo in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: phase III trial of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 80303) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3617–3622. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ychou M, Conroy T, Seitz JF, Gourgou S, Hua A, Mery-Mignard D, Kramar A. An open phase I study assessing the feasibility of the triple combination: oxaliplatin plus irinotecan plus leucovorin/ 5-fluorouracil every 2 weeks in patients with advanced solid tumors. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:481–489. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Von Hoff DD, Ramanathan RK, Borad MJ, Laheru DA, Smith LS, Wood TE, Korn RL, Desai N, Trieu V, Iglesias JL, et al. Gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel is an active regimen in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase I/II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4548–4554. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.5742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, Chiorean EG, Infante J, Moore M, Seay T, Tjulandin SA, Ma WW, Saleh MN, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1691–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Goldstein D, El-Maraghi RH, Hammel P, Heinemann V, Kunzmann V, Sastre J, Scheithauer W, Siena S, Tabernero J, Teixeira L, et al. nab-Paclitaxel plus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer: long-term survival from a phase III trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:pii: dju413. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Peixoto RD, Ho M, Renouf DJ, Lim HJ, Gill S, Ruan JY, Cheung WY. Eligibility of Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer Patients for First-Line Palliative Intent nab-Paclitaxel Plus Gemcitabine Versus FOLFIRINOX. Am J Clin Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000193. Apr 1; Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ho MY, Kennecke HF, Renouf DJ, Cheung WY, Lim HJ, Gill S. Defining Eligibility of FOLFIRINOX for First-Line Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma (MPC) in the Province of British Columbia: A Population-based Retrospective Study. Am J Clin Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000205. Jul 9; Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Giordano G, Febbraro A, Milella M, Vaccaro V, Melisi D, Foltran L, Zagonel V, Zaniboni A, Bertocchi P, Bergamo F, et al. Impact of second-line treatment (2L T) in advanced pancreatic cancer (APDAC) patients (pts) receiving first line Nab-Paclitaxel (nab-P) Gemcitabine (G): an Italian multicentre real life experience. American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting. 2016;34:suppl: abstr 4124. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chiorean EG, Von Hoff DD, Tabernero J, El-Maraghi R, Ma WW, Reni M, Harris M, Whorf R, Liu H, Li JS, et al. Second-line therapy after nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine or after gemcitabine for patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2016;115:188–194. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pelzer U, Schwaner I, Stieler J, Adler M, Seraphin J, Dörken B, Riess H, Oettle H. Best supportive care (BSC) versus oxaliplatin, folinic acid and 5-fluorouracil (OFF) plus BSC in patients for second-line advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III-study from the German CONKO-study group. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1676–1681. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Oettle H, Riess H, Stieler JM, Heil G, Schwaner I, Seraphin J, Görner M, Mölle M, Greten TF, Lakner V, et al. Second-line oxaliplatin, folinic acid, and fluorouracil versus folinic acid and fluorouracil alone for gemcitabine-refractory pancreatic cancer: outcomes from the CONKO-003 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2423–2429. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.6995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gill S, Ko YJ, Cripps C, Beaudoin A, Dhesy-Thind S, Zulfiqar M, Zalewski P, Do T, Cano P, Lam WY, et al. PANCREOX: A Randomized Phase III Study of 5-Fluorouracil/Leucovorin With or Without Oxaliplatin for Second-Line Advanced Pancreatic Cancer in Patients Who Have Received Gemcitabine-Based Chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2016 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.5776. Sep 12; Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang-Gillam A, Li CP, Bodoky G, Dean A, Shan YS, Jameson G, Macarulla T, Lee KH, Cunningham D, Blanc JF, et al. Nanoliposomal irinotecan with fluorouracil and folinic acid in metastatic pancreatic cancer after previous gemcitabine-based therapy (NAPOLI-1): a global, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;387:545–557. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00986-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Neesse A, Michl P, Frese KK, Feig C, Cook N, Jacobetz MA, Lolkema MP, Buchholz M, Olive KP, Gress TM, et al. Stromal biology and therapy in pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2011;60:861–868. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.226092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Neesse A, Algül H, Tuveson DA, Gress TM. Stromal biology and therapy in pancreatic cancer: a changing paradigm. Gut. 2015;64:1476–1484. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xie D, Xie K. Pancreatic cancer stromal biology and therapy. Genes Dis. 2015;2:133–143. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hurwitz HI, Uppal N, Wagner SA, Bendell JC, Beck JT, Wade SM, Nemunaitis JJ, Stella PJ, Pipas JM, Wainberg ZA, et al. Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase II Study of Ruxolitinib or Placebo in Combination With Capecitabine in Patients With Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer for Whom Therapy With Gemcitabine Has Failed. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:4039–4047. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.4578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cutsem EV, Lenz H, Furuse J, Tabernero J, Heinemann V, Ioka T, Bazin I, Ueno M, CsÃszi T, Wasan H, et al. MAESTRO: A randomized, double-blind phase III study of evofosfamide (Evo) in combination with gemcitabine (Gem) in previously untreated patients (pts) with metastatic or locally advanced unresectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting. 2016;34:suppl: abstr 4007. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bullock AJ, Hingorani SR, Wu XW, Jiang P, Chondros D, Khelifa S, Aldrich C, Pu J, Hendifar AE. Final analysis of stage 1 data from a randomized phase II study of PEGPH20 plus nab-Paclitaxel/gemcitabine in stage IV previously untreated pancreatic cancer patients (pts), utilizing Ventana companion diagnostic assay. American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting. 2016;34:suppl: abstr 4104. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Borazanci EH, Hong DS, Gutierrez M, Rasco DW, Reid TR, Veeder MH, Tawashi A, Lin J, Dimery IW. Ibrutinib durvalumab (MEDI4736) in patients (pts) with relapsed or refractory (R/R) pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAC): A phase Ib/II multicenter study. American Society of Clinical Oncology Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium; 2016. pp. suppl–4S: abstr TPS484. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jordan E, Lowery MA, Ptashkin R, Zehir A, Berger MF, Maynard H, Glassman DC, Covington CM, Schultz N, Abou-Alfa G, et al. Genomic profiling of pancreas ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA), actionability, and correlation with clinical phenotype. American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting. 2016;34:suppl: abstr 4127. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Salem ME, Marshall J, Feldman R, Pishvaian MJ, El-Deiry W, Hwang JJ, Lou E, Wang H, Gatalica Z, Reddy SK, et al. Comparative molecular analyses of pancreatic cancer (PC): KRAS wild type vs. KRAS mutant tumors and primary tumors vs. distant metastases. American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting. 2016;34:suppl: abstr 4130. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Melisi D, Garcia-Carbonero R, Macarulla T, Pezet D, Deplanque G, Fuchs M, Trojan J, Oettle H, Kozloff M, Cleverly A, et al. A phase II, double-blind study of galunisertib gemcitabine (GG) vs gemcitabine placebo (GP) in patients (pts) with unresectable pancreatic cancer (PC). American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting. 2016;34:suppl: abstr 4019. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Boyd J, Sonoda Y, Federici MG, Bogomolniy F, Rhei E, Maresco DL, Saigo PE, Almadrones LA, Barakat RR, Brown CL, et al. Clinicopathologic features of BRCA-linked and sporadic ovarian cancer. JAMA. 2000;283:2260–2265. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.17.2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chetrit A, Hirsh-Yechezkel G, Ben-David Y, Lubin F, Friedman E, Sadetzki S. Effect of BRCA1/2 mutations on long-term survival of patients with invasive ovarian cancer: the national Israeli study of ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:20–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.6905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vollebergh MA, Lips EH, Nederlof PM, Wessels LF, Wesseling J, Vd Vijver MJ, de Vries EG, van Tinteren H, Jonkers J, Hauptmann M, et al. Genomic patterns resembling BRCA1- and BRCA2-mutated breast cancers predict benefit of intensified carboplatin-based chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:R47. doi: 10.1186/bcr3655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Isakoff SJ, Mayer EL, He L, Traina TA, Carey LA, Krag KJ, Rugo HS, Liu MC, Stearns V, Come SE, et al. TBCRC009: A Multicenter Phase II Clinical Trial of Platinum Monotherapy With Biomarker Assessment in Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1902–1909. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.6660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Byrski T, Gronwald J, Huzarski T, Grzybowska E, Budryk M, Stawicka M, Mierzwa T, Szwiec M, Wisniowski R, Siolek M, et al. Pathologic complete response rates in young women with BRCA1-positive breast cancers after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:375–379. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Aung KL, Holter S, Borgida A, Connor A, Pintilie M, Dhani NC, Hedley DW, Knox JJ, Gallinger S. Overall survival of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma and BRCA1 or BRCA2 germline mutation. American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting. 2016;34:suppl: abstr 4123. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Golan T, Oh D, Reni M, Macarulla TM, Tortora G, Hall MJ, Reinacher-Schick A, Borg C, Hochhauser D, Walter T, et al. POLO: A randomized phase III trial of olaparib maintenance monotherapy in patients (pts) with metastatic pancreatic cancer (mPC) who have a germline BRCA1/2 mutation (gBRCAm). American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting. 2016;34:suppl: abstr TPS4152. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Domchek SM, Hendifar AE, McWilliams RR, Geva R, Epelbaum R, Biankin A, Vonderheide RH, Wolff RA, Alberts SR, Giordano H, et al. RUCAPANC: An open-label, phase 2 trial of the PARP inhibitor rucaparib in patients (pts) with pancreatic cancer (PC) and a known deleterious germline or somatic BRCA mutation. American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting. 2016;34:suppl: abstr 4110. [Google Scholar]