Abstract

Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare, potentially fatal, haematological disorder, which can be clinically challenging to diagnose and manage. We report a case of HLH in a previously healthy 33-year-old primigravida. The patient presented at 22 weeks gestation with dyspnoea, abdominal pain, anaemia, thrombocytopenia and elevated liver enzymes suggestive of HELLP syndrome.HELLP, a syndrome characterised by haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets is considered a severe form of pre-eclampsia. Despite delivery of the fetus, her condition deteriorated over 3–4 days with high-grade fever, worsening thrombocytopenia and anaemia requiring transfusion support. A bone marrow biopsy showed haemophagocytosis and a diagnosis of HLH was made. Partial remission was achieved with etoposide-based chemotherapy and complete remission following bone marrow transplantation. Eleven months post-transplant, the disease aggressively recurred, and the patient died within 3 weeks of relapse.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Obstetrics and gynaecology, Haematology (incl blood transfusion)

Background

Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a syndrome of pathological immune activation characterised by signs and symptoms of extreme inflammation.1 This disease can be divided into primary HLH and secondary HLH. Primary HLH refers to a familial form where defects in perforin function and other cytosolic pathways are attributed to disease. Secondary HLH refers to a sporadic or acquired form, which has been attributed to a variety of autoimmune syndromes, rheumatological diseases, immunodeficiencies and infections, particularly viruses such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV).2–5 Its diagnosis is based on the Histiocyte Society HLH Study group, which requires either a genetic mutation associated with HLH (PRF1, UNC13D, STXBP1, RAB27A, STX11) or five of the following: (1) fever (>38°C), (2) splenomegaly, (3) cytopenia affecting at least two lineages in the peripheral blood, (4) hypertriglyceridaemia and/or hypofibrinogenaemia, (5) haemophagocytosis in the bone marrow, spleen, lymph nodes or liver, (6) low or absent natural killer cell activity, (7) ferritin >500 mg/L and (8) soluble CD25 (soluble interleukin 2 (IL-2) receptor) >2400 IU/mL.6 HLH is rarely described during pregnancy and clinical management appears inconsistent across 17 published cases (table 1). Here, we report a case of pregnancy-related HLH, which was initially successfully treated with delivery, etoposide-based chemotherapy and allogenic bone marrow transplantation. Following 11 months in remission, the disease aggressively recurred and the patient died within 3 weeks of relapse.

Table 1.

Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in pregnancy

| Author | Age (years) | Gestational age (weeks) | Associated diagnosis | Clinical presentation | Treatment | Outcome | Mode of delivery |

| Nakabayashi et al 16 | 30 | 21 | Pre-eclampsia | Fever, pancytopenia, elevated LDH, ferritin | Antibiotics and Ig | Failed | 29 weeks CS |

| Antithrombin concentrate | Remission | ||||||

| Yamaguchi et al 17 | – | – | HSV2 | Fever, pancytopenia, elevated ferritin, triglycerides, sIL-2R | Corticosteroids | Failed | Term VD |

| Ciclosporin A | Remission | ||||||

| Hanaoka et al 18 | 33 | 21 | B-cell lymphoma | Fever, hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia, elevated ferritin, TG, LDH, sIL-2R | R-CHOP chemotherapy and emergent CS | Remission | 28 weeks CS |

| Dunn et al 10 | 41 | 19 | Still’s disease | Rash, fever and headache, anaemia, elevated ferritin, TG, LDH | High-dose corticosteroids and delivery | Remission | 30 weeks CS |

| Mayama et al 19 | 28 | 19 | Parvovirus B19 | Fever, pancytopenia, elevated ferritin, LDH | Corticosteroids | Remission | 37 weeks VD |

| Teng et al 11 | 28 | 23 | AIHA | Fever, anaemia, thrombocytopenia, elevated ferritin, TG, LDH, sIL-2R | Steroids | No response | 29 weeks CS (fetal death at delivery) |

| Termination of pregnancy | Remission | ||||||

| Kim et al 20 | 29 | 12 | SLE | Fever, pancytopenia, elevated ferritin, TG, LDH | Splenectomy | Remission | 14 weeks TOP |

| Chmait et al 4 | 24 | 29 | EBV | Routine check-up: pancytopenia | Ig, acyclovir, delivery at 30th week | Death: DIC, multiple organ failure | 30 weeks CS |

| Klein et al 3 | 39 | 30 | EBV | Pancytopenia, elevated ferritin, sIL-2R | Steroids, ciclosporin A, etoposide, rituximab | Death: multiple organ failure, sepsis | 31 weeks CS |

| Ota et al 21 | 26 | 23 | Liver abscess | Fever, thrombocytopenia, elevated ferritin, TG, LDH, sIL-2R | None | Death: cardiopulmonary arrest | – |

| Pérard et al 22 | 28 | 22 | SLE | Fever, pancytopenia, elevated ferritin, TG | Corticosteroids | Failed | 30 weeks VD |

| IVIG | Remission | ||||||

| Chien et al 23 | 28 | 23 | – | Fever, anaemia, thrombocytopenia, elevated TG | CS delivery | Remission | CS |

| Tumian and Wong5 | 35 | 38 | CMV | Fever, anaemia, jaundice, elevated ferritin, TG, LDH, sIL-2R | CS delivery, steroids and ciclosporin A | Death: multiple organ failure | CS |

| Arewa and Ajadi24 | 31 | 21 | HIV | Jaundice, fever, abdominal pain, anaemia, thrombocytopenia | HAART and delivery | Remission | Term VD |

| Shukla et al 25 | 23 | 10 | – | Fever, pancytopenia, elevated ferritin, TG | Corticosteroids | Failed | – |

| Spontaneous abortion | Remission | ||||||

| Samra et al 9 | 36 | 16 | – | Fever, pancytopenia, elevated ferritin, TG | Corticosteroids | Remission | Term VD |

| Mihara et al 2 | 32 | 16 | EBV | Fever, pancytopenia, elevated ferritin, LDH, sIL-2R | Corticosteroids, acyclovir | Failed | 35 weeks VD |

| IVIG | Remission | ||||||

| Our patient | 33 | 22 | – | Dyspnoea, abdominal pain, anaemia, thrombocytopenia, raised ferritin, LDH | Corticosteroids | Failed | 22 VD (fetal death at delivery) |

| Delivery, etoposide, BMT | Remission |

AIHA, autoimmune haemolytic anaemia; BMT, bone marrow transplantation; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CS, caesarean section; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy; HLH, haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; HSV, herpes simplex virus; Ig, immunoglobulin; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; R-CHOP, rituximab/cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/vincristine/prednisone; sIL-2R, soluble interleukin-2 receptor; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; TOP, termination of pregnancy; TG, triglycerides; VD, vaginal delivery.

Case presentation

A previously healthy 33-year-old primigravida presented at 22 weeks gestation with 1 week history of dyspnoea along with epigastric, shoulder and back pain. The patient’s medical and family history was unremarkable. She was apyrexial, tachycardic (142 beats/min), normotensive (124/80 mm Hg) and tachypnoeic (24 breaths/min) with an oxygen saturation of 96% on room air. Physical examination did not reveal any rash, arthritis, lymphadenopathy or organomegaly. Laboratory studies showed a mild anaemia (haemoglobin 11.3 g/dL), moderate thrombocytopenia (platelet count of 86×109/L), elevated liver enzymes (alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 105 IU/L) and raised D-dimers (1.78 mg/L). Her lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was slightly elevated at 305 IU/L. Peripheral blood smear showed a hypochromia and a CT pulmonary angiogram was normal. Her condition continued to deteriorate requiring oxygen therapy to maintain O2 saturations of 96%. She developed severe epigastric pain. Platelet count fell to 62×109/L and haemoglobin to 9.4 g/dL. Clinical suspicion was high for an atypical hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelet count (HELLP) syndrome and urgent delivery of the fetus was indicated. Labour was medically induced and the patient delivered a live female infant who died within minutes of delivery. Over the next 24 hours, she developed a high-grade fever and was commenced on intravenous broad spectrum antibiotics.

Investigations

A chest X-ray revealed a right basal pneumonia and she became increasingly oedematous with an albumin level of 12 g/L. Further laboratory investigations showed a rising LDH level (777 IU/L), hyperferritinaemia (3815 ng/mL), progressive thrombocytopenia to 25×109/L and anaemia of 9.5 g/dL requiring transfusion support. She was also noted to have low levels of schistocytes in her blood film (1.7%). A CT of the abdomen revealed hepatosplenomegaly and moderate volume ascites. A bone marrow aspirate and trephine biopsy was ordered 14 days postpartum, which revealed haemophagocytosis in the bone marrow. MRI of the brain was performed, which revealed an incidental pineal cyst. Results of genetic testing showed a normal perforin expression and granule release assay. Viral serology studies were also negative for EBV and CMV.

Differential diagnosis

Our patient had fever, splenomegaly, cytopenia affecting two lineages in the peripheral blood (haemoglobin <9 g/dL and platelets <100×109/L), haemophagocytosis in bone marrow and ferritin >500 µg/L fulfilling five out of eight criteria set out in the HLH 2004 trial. This supports a diagnosis of HLH.6 Given the patient’s age, secondary HLH was most likely. The acquired form can develop at any age and is usually secondary to infections (mycobacterium, EBV, CMV, HIV, herpes and protozoal infections), drug exposure (immunomodulatory drugs), autoimmune inflammatory disease (systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Still’s disease) and malignancies (eg, leukaemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma, hepatocellular carcinoma and germ-cell tumours).7 8

Treatment

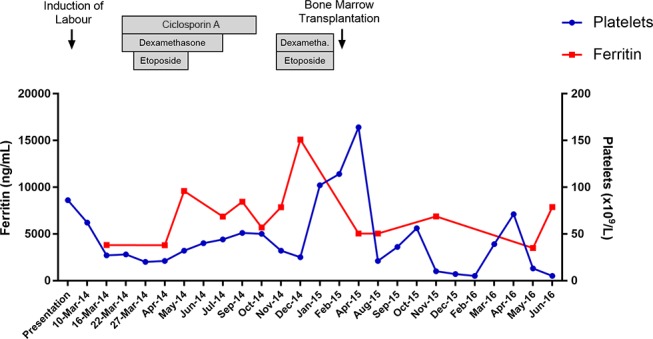

Initial treatment consisted of dexamethasone and ciclosporin as per the HLH-2004 protocol.6 She deteriorated a week later with profound hypotension, tachycardia and sudden worsening cytopenias (haemoglobin 7.7 g/dL; platelets 16×109/L), hypofibrinogenaemia (0.3 g/L) and a rising prothrombin time (12.2 s). She developed shock, required inotropes and transfer to intensive care unit. Once stabilised, she continued her chemotherapy for 8 weeks. Her albumin improved to 37 IU/L and her transfusion requirement diminished over weeks. Once her platelet count improved, a lumbar puncture was performed with intrathecal methotrexate administration as per protocol.6 Repeat bone marrow biopsy showed partial remission. Following this, her anaemia and thrombocytopenia remained stable but her ferritin continued to rise (>15 000 IU/L) requiring admission again for further chemotherapy (figure 1). Her ferritin level reduced to 5041 IU/L following further etoposide-based therapy. Given the likely histiocyte cell burden reflected by her ferritin levels, the patient underwent allogenic bone marrow transplant with curative intent 3 months later.

Figure 1.

Timeline of platelet and ferritin levels over the course of the disease.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient went into remission following transplant and had a good quality of life. However, 11 months post bone marrow transplant, her condition deteriorated with falling platelet (<10×109/L), white cell (1.0×109/L) and haemoglobin (9.3 g/dL) counts. An initial bone marrow biopsy showed no trace of HLH. However, 2 weeks later in the face of worsening cytopenia, the patient became symptomatic and a further biopsy showed over 60% infiltration with HLH cells and haemophagocytosis. At this time, she developed systemic symptoms of severe oedema, fatigue, malaise and severe pain in her right knee and hip. She was treated with methylprednisolone, etoposide and cyclophosphamide for palliation. Following 3 days at home with her family, she died of her disease.

Discussion

Pregnancy-associated HLH is a rare entity and to our knowledge only 17 case reports have been published to date (table 1). Fever with or without pancytopenia was the predominant clinical finding in HLH cases described in pregnant women.9 For a pregnant patient who presents with fever, low platelet counts and elevated liver enzymes, a differential diagnosis of HELLP syndrome, sepsis, cholestasis of pregnancy and acute fatty liver of pregnancy should always be considered. Following delivery, the clinical features of HELLP syndrome typically resolve while the available case reports of pregnancy-related HLH suggest it follows a more progressive course.4 10 11 Haemophagocytosis on histology is often a late feature and is not necessary for a diagnosis as per HLH criteria. Ferritin levels greater than 500 µg/L (in the absence of other causes of hyperferritinaemia) have a sensitivity of 84% and greater than 10 000 µg/L have 90% sensitivity and 96% specificity.12 13 Therefore, a pronounced hyperferritinaemia in the setting of systemic signs and symptoms along with a negative infection screen should raise suspicions of HLH.

There is no established treatment guideline for pregnancy-related HLH to date. In general, the treatment of secondary HLH includes three main components: (1) identification and treatment of the underlying cause; (2) inhibition of T-cell activation and proliferation and (3) inhibition of cytokine secretion and production. The treatment regime outlined in the HLH-94 protocol consists of 8 weeks of etoposide-based chemotherapy along with dexamethasone, ciclosporin and intrathecal methotrexate for those with CNS involvement.14 The HLH-94 protocol is currently recommended as the study results of the revised 2004 protocol have yet to be published.6 The HLH-94 regime achieved ~75% clinical remission after 8 weeks of treatment. At a median follow-up of 3.1 years, the estimated 3-year probability of survival overall was 55%.14 Of the 17 reported cases of pregnancy-associated HLH, at least 6 achieved complete remission following cessation of pregnancy. Kourtis et al 15 recently challenged the long-held belief that pregnancy is a state of immunosuppression and suggests it should be viewed as a modulated immunological condition. While the specific role of pregnancy in HLH has not been elucidated, it is likely that the cellular and humoral immune mediators in HLH are subject to pregnancy-related alterations.

Learning points.

A pronounced hyperferritinaemia in the setting of systemic signs and symptoms along with a negative infection screen should raise suspicions of haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH).

To our knowledge, this is the first known case of pregnancy-related HLH treated with allogenic bone marrow transplant, which achieved 11 months of complete remission.

The aggressive pace of the relapse in the post-transplant period signifies the aggressive nature of the condition and disease control or reinduction post allograft failure was not expected.

Footnotes

Contributors: RNK was primarily responsible for drafting the clinical case report. RMK assisted with literature review and collection of patient information. MRC and LCK provided clinical guidance and gave editorial feedback. All authors contributed to preparation of this case report.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained from next of kin.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Jordan MB, Allen CE, Weitzman S, et al. How I treat hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood 2011;118:4041–52. 10.1182/blood-2011-03-278127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mihara H, Kato Y, Tokura Y, et al. [Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome during mid-term pregnancy successfully treated with combined methylprednisolone and intravenous immunoglobulin]. Rinsho Ketsueki 1999;40:1258–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Klein S, Schmidt C, La Rosée P, et al. Fulminant gastrointestinal bleeding caused by EBV-triggered hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: report of a case. Z Gastroenterol 2014;52:354–9. 10.1055/s-0034-1366154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chmait RH, Meimin DL, Koo CH, et al. Hemophagocytic syndrome in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95:1022–4. 10.1097/00006250-200006001-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tumian NR, Wong CL. Pregnancy-related hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with cytomegalovirus infection: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2015;54:432–7. 10.1016/j.tjog.2014.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. HLH-2004: diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007;48:124–31. 10.1002/pbc.21039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aryal MR, Badal M, Giri S, et al. Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis mimicking septic shock after the initiation of chemotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the neck. BMJ Case Rep 2013;2013:bcr2013009651 10.1136/bcr-2013-009651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Deane S, Selmi C, Teuber SS, et al. Macrophage activation syndrome in autoimmune disease. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2010;153:109–20. 10.1159/000312628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Samra B, Yasmin M, Arnaout S, et al. Idiopathic Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis during Pregnancy treated with steroids. Hematol Rep 2015;7:6100 10.4081/hr.2015.6100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dunn T, Cho M, Medeiros B, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in pregnancy: a case report and review of treatment options. Hematology 2012;17:325–8. 10.1179/1607845412Y.0000000007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Teng CL, Hwang GY, Lee BJ, et al. Pregnancy-induced hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis combined with autoimmune hemolytic anemia. J Chin Med Assoc 2009;72:156–9. 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70043-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tsuda H, Shirono K. Successful treatment of virus-associated haemophagocytic syndrome in adults by cyclosporin A supported by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Br J Haematol 1996;93:572–5. 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.d01-1707.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ravelli A, Viola S, De Benedetti F, et al. Dramatic efficacy of cyclosporine A in macrophage activation syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2001;19:108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Henter JI, Samuelsson-Horne A, Aricò M, et al. Treatment of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with HLH-94 immunochemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation. Blood 2002;100:2367–73. 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kourtis AP, Read JS, Jamieson DJ. Pregnancy and infection. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2211–8. 10.1056/NEJMra1213566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nakabayashi M, Adachi T, Izuchi S, et al. Association of hypercytokinemia in the development of severe preeclampsia in a case of hemophagocytic syndrome. Semin Thromb Hemost 1999;25:467–71. 10.1055/s-2007-994952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yamaguchi K, Yamamoto A, Hisano M, et al. Herpes simplex virus 2-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in a pregnant patient. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105:1241–4. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000157757.54948.9b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hanaoka M, Tsukimori K, Hojo S, et al. B-cell lymphoma during pregnancy associated with hemophagocytic syndrome and placental involvement. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma 2007;7:486–90. 10.3816/CLM.2007.n.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mayama M, Yoshihara M, Kokabu T, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with a Parvovirus B19 infection during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2014;124(2 Pt 2 Suppl 1):438–41. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim JM, Kwok SK, Ju JH, Jh J, et al. Macrophage activation syndrome resistant to medical therapy in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus and its remission with splenectomy. Rheumatol Int 2013;33:767–71. 10.1007/s00296-010-1654-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ota K, Kawahara K, Banno H, et al. Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis caused by pyogenic liver abscess during Pregnancy: a Case Report and Literature Review. Open J Obstet Gynecol 2016;06:287–92. 10.4236/ojog.2016.65036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pérard L, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Limal N, et al. Hemophagocytic syndrome in a pregnant patient with systemic lupus erythematosus, complicated with preeclampsia and cerebral hemorrhage. Ann Hematol 2007;86:541–4. 10.1007/s00277-007-0277-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chien CT, Lee FJ, Luk HN, et al. Anesthetic management for cesarean delivery in a parturient with exacerbated hemophagocytic syndrome. Int J Obstet Anesth 2009;18:413–6. 10.1016/j.ijoa.2009.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arewa OP, Ajadi AA. Human immunodeficiency virus associated with haemophagocytic syndrome in pregnancy: a case report. West Afr J Med 2011;30:66–8. 10.4314/wajm.v30i1.69922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shukla A, Kaur A, Hira HS. Pregnancy induced haemophagocytic syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol India 2013;63:203–5. 10.1007/s13224-011-0073-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]