Abstract

Acute massive gastric dilatation (AMGD) is a rare distinctive condition but associates with high morbidity and mortality. Though usually seen in patients with eating disorders, many aetiologies of AMGD have been described. The distension has been reported to cause gastric necrosis with or without perforation, usually within 1–2 days of an inciting event of AMGD.

We report the case of a 58-year-old male who presented with gastric perforation associated with AMGD 11 days after surgical relief of a proximal small bowel obstruction. The AMGD arose from a closed loop obstruction between a tumour at the gastro-oesophageal junction and a small bowel obstruction as a result of volvulus around a jejunal feeding tube.

To our knowledge, this is the first case of a closed loop obstruction of this aetiology reported in the literature, and the presentation of this patient’s AMGD was notable for the delayed onset of gastric necrosis. The patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy and a partial gastrectomy to excise a portion of his perforated stomach. Surgeons should be aware of the possibility of delayed ischaemic gastric perforation in cases of AMGD.

Keywords: stomach and duodenum, general surgery

Background

Gastric perforation secondary to acute gastric distension has been reported in several case reports, and usually presents within 24 hours of the onset of distension.1 2 We present the case of a 58-year-old male who developed acute massive gastric dilatation (AMGD) following jejunal obstruction due to jejunal volvulus around a jejunostomy tube. He subsequently presented with an acute abdomen 11 days after relief of his small bowel obstruction and was found to have an ischaemic gastric perforation.

The patient’s jejunal obstruction was caused by a loop of small bowel volvulating around the jejunostomy feeding tube site, in effect forming a closed loop obstruction between his distal oesophageal tumour and the point of jejunal obstruction. We report the delayed presentation of gastric perforation despite the surgical treatment of his jejunal obstruction.

Case presentation

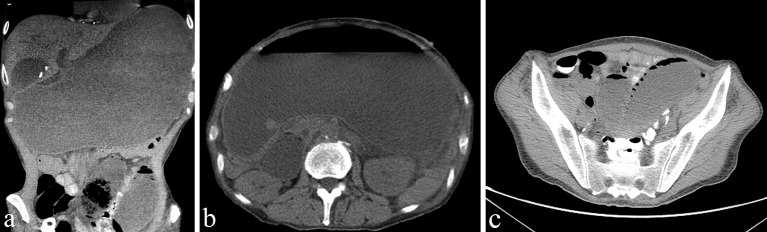

A 58-year-old male presented to an outside institution with 2 days of diffuse abdominal pain and distension. One month prior to presentation, he had been diagnosed with a T3N1 oesophageal adenocarcinoma and had undergone jejunal feeding tube placement for enteral access with a plan to undergo neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy prior to oesophagogastrectomy. He had complained of intermittent nausea and tube feeding intolerance since the placement of his feeding tube. The patient underwent a CT scan of the abdomen that revealed massive gastric distension of unclear aetiology (figure 1) and was referred to our institution for further evaluation.

Figure 1.

Coronal (A) and axial (B, C) sections of a CT of the abdomen demonstrating acute massive gastric dilatation and proximal jejunal dilatation.

Initial examination revealed a markedly distended abdomen, which was tender but with no evidence of peritonism. He was afebrile with a heart rate of 88 bpm and blood pressure of 113/80 mm Hg. He was oliguric, though his urine output improved after resuscitation with intravenous fluids. Laboratory investigations revealed that blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels were elevated to 50 mg/dL (normal range 10 mg/dL–25 mg/dL) and 1.8 mg/dL (normal range 0.70 mg/dL–1.40 mg/dL) from baseline levels of 13 mg/dL and 1.2 mg/dL, respectively. He was resuscitated aggressively and a nasogastric (NG) tube was advanced carefully past the distal oesophageal tumour for gastric decompression. Ten litres of gastric contents were removed with immediate obvious improvement in his abdominal examination.

An abdominal CT scan was repeated after gastric decompression and revealed a transition point in the small bowel at the level of the jejunal feeding tube site. The patient was taken to the operating room for a diagnostic laparoscopy. The operative findings included a volvulus of the distal jejunum around the jejunostomy tube site causing small bowel obstruction. The small bowel was reduced laparoscopically, and the jejunum was pexied to the abdominal wall proximally and distally to prevent recurrent volvulus. A thorough inspection of the stomach was performed but no gastric ischaemia was noted. The patient recovered from his operation and was discharged uneventfully on postoperative day 9. His nausea was improved, and he was tolerating his tube feeds at his goal rate for over 24 hours prior to discharge.

Two days later, on postoperative day 11, he presented to the emergency department of an outside hospital with acute worsening abdominal pain. His abdominal examination revealed involuntary guarding consistent with peritonitis. Haemodynamic instability was noticed with a heart rate of 144 bpm and blood pressure of 63/37 mm Hg. Pneumoperitoneum was demonstrated on his abdominal radiograph. Laboratory investigations showed a haemoglobin of 8.1 g/dL from a baseline of 10.1 g/dL. He was resuscitated with 4 L of crystalloid and 3 units of packed red blood cells with limited response and so was commenced on the vasopressor norepinephrine. With these interventions, his blood pressure improved to 109/75 mm Hg. Once haemodynamically stable, he was transferred to our institution with a diagnosis of septic shock and pneumoperitoneum.

On arrival, he was tachycardic with a heart rate of 144 bpm and hypotensive at 87/59 mm Hg. Examination of his abdomen revealed generalised peritonitis. His BUN was 38 mg/dL, serum creatinine was 1.1 mg/dL and he had an elevated serum lactic acid at 4.5 mmol/L. He was resuscitated in the surgical intensive care unit and taken to the operating room for an exploratory laparotomy.

Treatment

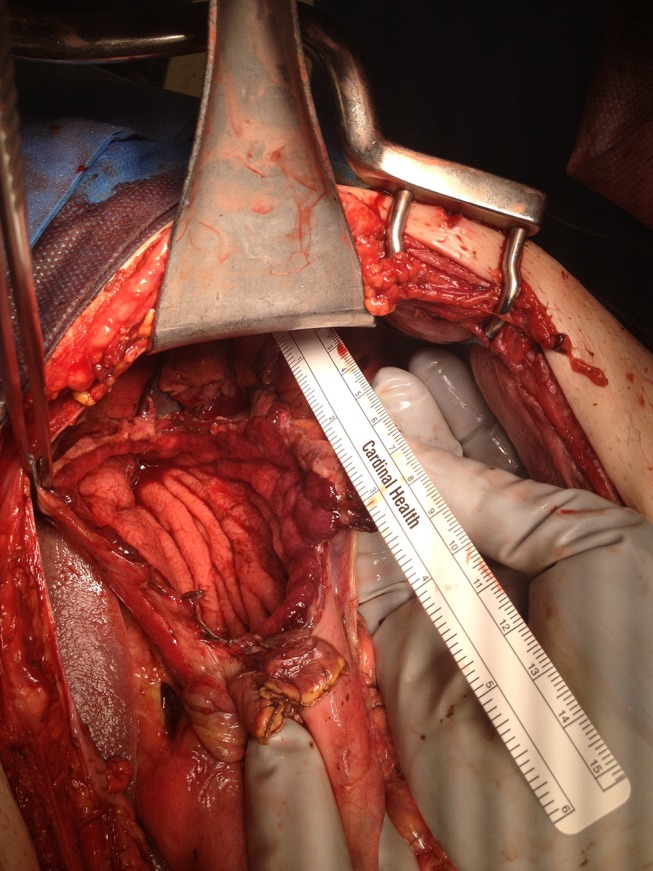

The abdomen was entered by a midline laparotomy incision and 2 L of succus entericus was removed. The stomach was no longer dilated, and a 15 cm perforation was seen in the anterior gastric body along the greater curvature. The perforation was separated from a palpable tumour at the gastro-oesophageal junction by 8 cm (figure 2). A stapled partial gastrectomy was performed, and an NG tube was placed intraoperatively for postoperative gastric decompression. Two intraperitoneal drains were placed in the vicinity of the suture line. His postoperative recovery was uneventful and he was discharged 12 days after his partial gastrectomy. Histopathology of the resection specimen revealed a gastric perforation associated with ischaemic ulceration.

Figure 2.

Gastric perforation. A 15 cm perforation on the anterior wall of the stomach along the greater curvature.

Outcome and follow-up

He presented again 3 weeks after his last operation with perihepatic abscess which was drained percutaneously by intervention radiology and completed 6 weeks of intravenous antibiotic treatment. A subsequent CT scan showed resolution of the abscess. The patient expired 4 months later due to metastatic oesophageal adenocarcinoma.

Discussion

Acute gastric distension, first reported by Duplay in 1833, is a rare but serious condition with high mortality due to the development of sequelae such as gastric emphysema, gangrene and perforation.1–4 AMGD is the extreme presentation of acute gastric distension in which the stomach occupies both the left and right sides of the abdomen from diaphragm to pelvis, and a wide variety of causes have been described. Several aetiologies have been postulated to explain the pathogenesis including binge eating disorders, small bowel obstruction, postoperative gastric distension, anaesthesia and debilitation, gastric cancer and an overly tight wrap following a Nissen fundoplication.2–11

Without intervention, this condition results in high mortality from gastric perforation. Although stomach gangrene is rare due to the gastric rich blood supply, the pathophysiology of the perforation is related to gastric ischaemia due to the intraluminal pressures of the stomach exceeding the venous pressures.3 4 12 The pressures required to cause venous congestion have been cited at between 14 and 30 cm H2O, though there is no consensus on a minimum pressure required to achieve gastric necrosis.3 5 The location of perforation is most often along the greater curvature, and in contrast, the lesser curvature and pylorus are usually protected from ischaemia.3–5 13 14 In the current case, we hypothesise that AMGD arose as a result of a closed loop obstruction between the volvulated loop of jejunum and the near total obstructing distal oesophageal carcinoma. A thorough inspection of the stomach was performed but no gastric ischaemia or free air was noted during the initial surgery. It is unlikely that it had perforated at that time as the patient represented 11 days later. To our knowledge, this is the first case report of a closed loop obstruction with this aetiology reported in the literature, and the patient’s AMGD from this closed loop obstruction was notable for the delayed onset of gastric necrosis.

The initial presentation may vary but the patient usually presents with a history consistent with recent binge eating or another cause of gastric distension. Emesis is present in over 90% of cases3 and is often coffee-ground in colour.1 15 An inability to vomit may also be present if it accompanies an acute episode of binge eating and is usually associated with abdominal pain and gastric distension.3 This sensation of the inability to vomit is believed to be due to the gastric distension causing a compressive angulation of the gastro-oesophageal junction during an episode of AMGD.1

The gastric distension may be evident on an abdominal radiograph, and a CT scan of the abdomen may assist in delineating an anatomical cause of the distension, as in our reported case.2 Decompression by NG tube will usually reveal a large volume of gastric fluid and is therapeutic in relieving the distension during resuscitation.5 8 Ultimately, however, operative intervention to relieve the cause of the obstruction and evaluate the gastric tissue is required if the patient fails to improve; delay in operative management has resulted in mortality as high as 80% in published data.3

The operative management of AMGD in the literature varies somewhat by the cause. There are two main considerations in the treatment of AMGD, the first of which is relieving the distension. This has been accomplished in multiple ways depending on the cause, but most commonly by NG decompression for binge episodes.16–19 Other methods have included decompressive gastrostomy20 or operative relief of a duodenal obstruction in the case of superior mesenteric artery syndrome.21 The second consideration is monitoring and treatment of the gastric necrosis or perforation. The most commonly reported method is either partial or total gastric resection.1 7 16 22–25 However, depending on the viability of the tissue, gastrorrhaphy has been reported.26

This is the first case report in the literature of a closed loop obstruction between a tumour at the gastro-oesophageal junction and a transition point of small bowel obstruction resulting from volvulus of a loop of bowel around a jejunostomy feeding tube. The patient’s AMGD was also notable for the delay in presentation of gastric necrosis. This delayed presentation, 11 days following relief of the obstruction and gastric distension, is unusual in that previously reported cases were presented within 1–2 days of a causative episode of AMGD. Patients with AMGD should be monitored for the development of gastric necrosis after the causative factor has been relieved, as the sequelae may present in a delayed fashion.

Learning points.

Acute massive gastric dilatation (AMGD) is a rare but serious condition with high mortality.

Closed loop obstruction is a rare cause for AMGD.

Delay in operative management results in mortality as high as 80%.

Relieving of the distension and management of the gastric necrosis or perforation are the mainstay of AMGD treatment.

Footnotes

Contributors: MAM wrote, revised the paper and was involved in the planning, conduct, reporting, conception and design, acquisition of data and analysis and interpretation of data. JM participated in the planning, conduct, reporting, conception and design, acquisition of data and analysis and interpretation of data. GF participated in the planning, conduct, reporting, conception and design, acquisition of data and analysis and interpretation of data. JSU supervised the paper and provided feedback and direct revisions. GM-S is the senior author of the paper and he supervised and revised all the above.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained from next of kin.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Mishima T, Kohara N, Tajima Y, et al. Gastric rupture with necrosis following acute gastric dilatation: report of a case. Surg Today 2012;42:997–1000. 10.1007/s00595-012-0162-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turan M, Sen M, Canbay E, et al. Gastric necrosis and perforation caused by acute gastric dilatation: report of a case. Surg Today 2003;33:302–4. 10.1007/s005950300068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luncă S, Rikkers A, Stănescu A. Acute massive gastric dilatation: severe ischemia and gastric necrosis without perforation. Rom J Gastroenterol 2005;14:279–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steen S, Lamont J, Petrey L. Acute gastric dilation and ischemia secondary to small bowel obstruction. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2008;21:15–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turan M, Sen M, Canbay E, et al. Gastric necrosis and perforation caused by acute gastric dilatation: report of a case. Surg Today 2003;33:302–4. 10.1007/s005950300068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vettoretto N, Viotti F, Taglietti L, et al. Acute idiopathic gastric necrosis, perforation and shock. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2010;3:304 10.4103/0974-2700.66564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trindade EN, von Diemen V, Trindade MR. Acute gastric dilatation and necrosis: a case report. Acta Chir Belg 2008;108:602–3. 10.1080/00015458.2008.11680297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patuto N, Acklin Y, Oertli D, et al. Gastric necrosis complicating lately a nissen fundoplication. Report of a case. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2008;393:45–7. 10.1007/s00423-007-0216-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee D, Sung K, Lee JH. Acute gastric necrosis due to gastric outlet obstruction accompanied with gastric cancer and trichophytobezoar. J Gastric Cancer 2011;11:185–8. 10.5230/jgc.2011.11.3.185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gyurkovics E, Tihanyi B, Szijarto A, et al. Fatal outcome from extreme acute gastric dilation after an eating binge. Int J Eat Disord 2006;39:602–5. 10.1002/eat.20281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saul SH, Dekker A, Watson CG. Acute gastric dilatation with infarction and perforation. Report of fatal outcome in patient with anorexia nervosa. Gut 1981;22:978–83. 10.1136/gut.22.11.978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakao A, Isozaki H, Iwagaki H, et al. Gastric perforation caused by a bulimic attack in an anorexia nervosa patient: report of a case. Surg Today 2000;30:435–7. 10.1007/s005950050618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koyazounda A, Le Baron JC, Abed N, et al. [Gastric necrosis caused by acute gastric dilatation. Total gastrectomy. Recovery]. J Chir 1985;122:403–7. Article in French. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerstein MD, Goldberg B, Panter B, et al. Gastric infarction. Gastroenterology 1974;67:1238–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powell JL, Payne J, Meyer CL, et al. Gastric necrosis associated with acute gastric dilatation and small bowel obstruction. Gynecol Oncol 2003;90:200–3. 10.1016/S0090-8258(03)00204-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim HH, Park SJ, Park MI, et al. Acute gastric dilatation and acute pancreatitis in a patient with an eating disorder: solving a chicken and egg situation. Intern Med 2011;50:571–5. 10.2169/internalmedicine.50.4595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abu-Zidan FM, Hefny AF, Saadeldinn YA, et al. Sonographic findings of superior mesenteric artery syndrome causing massive gastric dilatation in a young healthy girl. Singapore Med J 2010;51:e184–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bravender T, Story L. Massive binge eating, gastric dilatation and unsuccessful purging in a young woman with bulimia nervosa. J Adolesc Health 2007;41:516–8. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barada KA, Azar CR, Al-Kutoubi AO, et al. Massive gastric dilatation after a single binge in an anorectic woman. Int J Eat Disord 2006;39:166–9. 10.1002/eat.20211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benson JR, Ward MP. Massive gastric dilatation and acute pancreatitis – a case of 'Ramadan syndrome'? Postgrad Med J 1992;68:689 10.1136/pgmj.68.802.689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veysi VT, Humphrey G, Stringer MD. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome presenting with acute massive gastric dilatation. J Pediatr Surg 1997;32:1801–3. 10.1016/S0022-3468(97)90541-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baldassarre E, Capuano G, Valenti G, et al. A case of massive gastric necrosis in a young girl with Rett syndrome. Brain Dev 2006;28:49–51. 10.1016/j.braindev.2005.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qin H, Yao H, Zhang J. Gastric rupture caused by acute gastric distention in non-neonatal children: clinical analysis of 3 cases. Chin Med J 2000;113:1147–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wharton RH, Wang T, Graeme-Cook F, et al. Acute idiopathic gastric dilation with gastric necrosis in individuals with Prader-Willi syndrome. Am J Med Genet 1997;73:437–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reeve T, Jackson B, Scott-Conner C, et al. Near-total gastric necrosis caused by acute gastric dilatation. South Med J 1988;81:515–7. 10.1097/00007611-198804000-00027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Idowu J, Razzouk AJ, Georgeson K. Visceral ischemia secondary to gastric dilatation: a rare complication of Nissen fundoplication. J Pediatr Surg 1987;22:939–40. 10.1016/S0022-3468(87)80594-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]