Abstract

A 75-year-old man was admitted with abdominal pain and fresh rectal bleeding. Significantly, he had no risk factors for Clostridium difficile infection. An abdominal CT demonstrated colonic thickening, and flexible sigmoidoscopy identified pseudomembranous colitis-like lesions. After initial treatment as C. difficile colitis, a stool sample revealed Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection. Antibiotic therapy was stopped due to the risk of lysis-mediated toxin release, but unfortunately, the patient continued to deteriorate. He developed several of the severe sequelae of E. coli O157:H7 infection, including haemolytic-uraemic syndrome with an acute kidney injury necessitating haemofiltration, plus progressively severe seizures requiring escalating antiepileptic treatment and intubation for airway protection. After a prolonged intensive care admission and subsequent recovery on the ward, our patient was discharged alive.

Keywords: infection (gastroenterology), endoscopy, epilepsy and seizures, acute renal failure

Background

July 2016 saw an outbreak of the phage type (PT) 34 Escherichia coli O157:H7 across the UK, with 161 cases eventually reported.1 This represents a particularly severe form of E. coli infection, with several known sequelae. Up to 9% of enterohaemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) O157:H7 infections are complicated by haemolytic-uraemic syndrome (HUS), a primary thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) syndrome which is characterised by microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia, acute kidney injury and thrombocytopaenia.2 3 Neurological involvement is recognised in 30% of cases, the most common manifestation of which is generalised or partial seizure activity.4

A severe colitis carrying many similarities to pseudomembranous colitis—which is classically associated with Clostridium difficile infection—as the presenting feature such as in this case, has been reported after Salmonella, Staphylococcus aureus and E. coli O157:H7 infections.5–7 Our case uniquely presented with E. coli-associated pseudomembranous colitis-like lesions and acute kidney injury secondary to HUS which progressed with neurological sequelae requiring airway protection.

Case presentation

A fully independent 75-year-old man with a medical history of metastatic prostate cancer was admitted to hospital with a 3-day history of lower abdominal pain, diarrhoea and three episodes of fresh blood per rectum. The patient had no recent travel history of note, could not recall consuming any extraordinary food items and had no unwell contacts. He was an ex-smoker with a 10 pack-year history, no evidence of alcohol excess, and prior to this admission was a carer for his wife, was independent with his activities of daily living and had an unlimited exercise tolerance. Other than advanced age, he had no risk factors for C. difficile infection (eg, recent antibiotic exposure, proton pump inhibitor exposure or prolonged hospital stay).8 On examination, abdomen was soft with mild suprapubic tenderness but no guarding or rigidity. Rectum examination was unremarkable. Respiratory, cardiovascular and neurological examinations on admission were normal. White cell count was raised on admission at 11.1×109/L with a neutrophilia of 9.78×109/L, and C reactive protein was 107 mg/L.

The patient was oliguric on admission with a normal serum creatinine of 86 µmol/L (estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) 76 mL/min) which increased on day 7 to 418 µmol/L (eGFR 11 mL/min). He was also found to have an elevated total bilirubin of 31 µmol/L (upper limit of normal 20 µmol/L). Also of note, on day 7, he had a serum urea of 39.3 mmol/L (normal range 2.5–7.8 mmol/L), a serum sodium of 136 mmol/L (normal range 133–146 mmol/L), a serum potassium of 4.4 mmol/L (normal range 3.5–5.3 mmol/L), an adjusted calcium of 2.23 mmol/L (upper limit of normal 2.60 mmol/L), a serum phosphate of 2.28 mmol/L (upper limit of normal 1.50 mmol/L), an albumin of 20 g/L (normal range 25–50 g/L), an alkaline phosphatase level of 136 U/L (upper limit of normal 130 U/L) and an alanine aminotransferase of 23 U/L (upper limit of normal 41 U/L). At this stage, his venous blood gas showed a pH of 7.42, a pCO2 of 4.8 (normal range 4.5–6.0 kPa), a pO2 of 4.8 kPa, a lactate of 1.0 (normal range 0.5–2.2 mmol/L) and a base excess of −0.7 (normal range −2 to 2). His full blood count on day 7 showed a haemoglobin of 127 g/L (normal range 130–180 g/L), a white cell count of 22.0 (normal range 3.6–11.0) and a platelet count of 74×109/L (normal range 140–400×109/L).

On day 11 of his admission, he had a short self-terminating generalised seizure, with upward rolling of the eyes, clenched fists and flexed posture.

Investigations

CT abdomen and pelvis on admission showed ‘thickening of the ascending, transverse and part of the descending colon, suggestive of a colitis’ (see figure 1).

E. coli O157:H7 PT34 (verotoxin gene positive, sequence type 11, stx subtype stx2a/stx2c and SNP address 5.156.1329.2502.2965.3081.3414) isolated from admission stool sample—result available on day 4 of admission, and Public Health England (PHE) was notified.

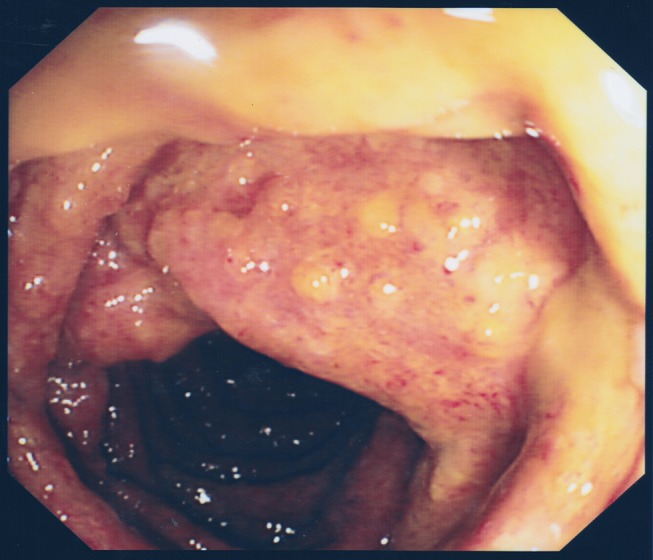

Flexible sigmoidoscopy on day 4 of admission showed ‘appearances of severe pseudomembranous colitis throughout the examined colon extending from the rectum to the mid transverse’ (see figure 2).

Biopsy from the flexible sigmoidoscopy showed ‘much of the surface epithelium is denuded and replaced by an exudate of fibrin, karyorrhectic debris and neutrophil polymorphs. Where intact, the mucosa shows significant crypt withering associated with active inflammation in the form of cryptitis and crypt abscess formation. The appearances are those of pseudomembranous colitis’.

Five days into the admission, a repeat CT showed that ‘the colon remains thickened and oedematous … the distal sigmoid and rectum are now also abnormal. The most dilated segment is the relatively normal looking caecum (7 cm). The thickened segments of the more proximal colon measure up to 4 cm’.

Blood film on day 5 of admission showed ‘neutrophilia with left shift; platelets mildly reduced; moderate number of red cell fragments present, moderate red cell crenation; there are red cell fragments present which would be consistent with a microangiopathic process’. Reticulocyte count at this point was 1.78% (normal range 0.2%–2.0%).

C. difficile toxin was not isolated on days 1, 7, 20 and 30 of admission, making C. difficile infection extremely unlikely.9 Testing was compliant with the PHE National Standards Methods for investigation and used the C. difficile Tox A/B II and C. diff Chek-60 enzyme immunoassays both from TechLab.

Initial doubt as to whether the apparent seizure episode was truly a seizure led to a concurrent serum prolactin to be taken; this was returned as 1022 mIU/L (upper limit of normal 450 mIU/L), evidence consistent with this episode having been a seizure.

Microscopy, culture and sensitivity testing from blood, urine and central line tip samples were persistently negative throughout admission.

CT brain performed on the day of seizure onset showed ‘a 10 mm well-defined area of rounded area of low attenuation in the right parietal lobe suggestive of an established area of damage, such as infarction’, but no new focal cause for the seizures.

Figure 1.

A transverse CT slice showing thickening of the transverse colon, suggestive of a colitis.

Figure 2.

Photograph taken at flexible sigmoidoscopy demonstrating appearances of severe pseudomembranous colitis.

Differential diagnosis

Ischaemic colitis—no specific risk factors present;

Inflammatory bowel disease—no personal or family history; endoscopic features not typical;

Infective colitis—other possible aetiological agents included EHEC, Salmonella spp, Shigella spp and C. difficile; the sigmoidoscopy finding of pseudomembranous colitis greatly escalated suspicion of C. difficile, with the identification of E. coli O157:H7 in the stool considerably changing the course of management;

Thrombotic thrombocytopaenic purpura (TTP), another primary TMA, was considered when the patient began to have seizures, but in the presence of a positive E. coli O157:H7 result and when coupled with his acute kidney injury, this pointed toward a diagnosis of HUS. Of note, our patient did not also have purpura on examination of the skin. Confidence in the diagnosis was increased as there had been other cases locally, although less severe.

Treatment

Our patient was discussed early with general surgery and was deemed for conservative management but was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) on day 5 of admission in anticipation of requiring renal replacement therapy. He started continuous veno-venous haemofiltration to manage his acute kidney injury—review by renal physicians recommended ongoing supportive care at this point.

With regard to antibiotic therapy, he was initially started on intravenous metronidazole 500 mg every 8 hours for presumed C. difficile infective colitis. Early on day 5, additional antibiotics (intravenous tigecycline, intravenous teicoplanin, intravenous metronidazole and oral vancomycin) were added. Later on day 5 of admission, in light of the positive E. coli O157:H7 result, the patient received a dose of intravenous immunoglobulin 0.4 g/kg, and all antibiotics were stopped due to the risk of bacterial lysis and toxin release.

A deterioration in the patient’s condition and seizure onset on day 11 of admission prompted a shift to broad-spectrum antibiotics to cover for possible translocation and bacterial sepsis—initially, 1 day of intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam was given but then was escalated to intravenous meropenem to improve central nervous system (CNS) cover. There was low suspicion that seizures were due to CNS infection though, and no lumbar puncture was performed. Meropenem continued for 7 days, when all antibiotics were stopped and the patient was stepped down to the ward environment.

With regard to seizure management, the patient was initially loaded with intravenous levetiracetam, to which sodium valproate was added when it was thought seizure activity was persisting throughout the night. Despite treatment, seizure activity gradually increased, and lack of improvement in his Glasgow Coma Scale score led to intubation the following day to protect his airway. An electroencephalogram while intubated did not show ictal activity, and he was extubated successfully the following day. Levetiracetam dose was increased to cover continuing myoclonic jerks and then stopped altogether 7 days later.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was discharged to a side room on the ward once stable and not requiring organ support. His renal function and stool habit gradually normalised on the ward after which he was successfully discharged home with a re-enablement care package. In total, our patient remained in the hospital for 43 days, 15 of which were spent in the ICU.

Discussion

Our case is the only one to date to the authors’ knowledge of pseudomembranous colitis resulting from E. coli O157:H7 infection (in the absence of C. difficile infection) associated with neurologically complicated HUS in an adult patient. Two other case reports of E. coli O157:H7 pseudomembranous colitis with C. difficile excluded exist in the literature, although one does not mention neurological involvement and the other is associated with TTP not HUS.10 11 One more recent case report of pseudomembranous colitis in E. coli O157:H7 infection describes a case in the absence of HUS in which progression to total colectomy was necessary.6

A feature of note in our case was the survival of the patient with supportive treatment despite poor prognostic features (elderly, requiring renal replacement therapy, comorbidities) in the face of a condition with considerable mortality.

Antibiotic therapy in E. coli O157:H7 infection is controversial, with studies suggesting they do not shorten duration of symptoms and that they may increase the risk of HUS through antibiotic-induced toxin release.12 13 However, results from the 2011 outbreak of E. coli O104:H4 in Germany showed no evidence of such toxin release with antibiotic therapy.14 In our case, empirical antibiotics were started when infective colitis was suspected, temporarily escalated due to concerns about sepsis and C. difficile and then stopped on microbiology advice following isolation of the E. coli O157:H7. The patient’s renal function had already started to deteriorate at this point, so it would be impossible to disentangle whether initial antibiotic therapy truly had precipitated HUS.

Learning points.

Although the most common cause of pseudomembranous colitis is Clostridium difficile, other causative organisms do exist including Escherichia coli O157:H7. Bear these organisms in mind if there is no clear recent history of antibiotic use.

Evidence on use of antibiotics in haemolytic-uraemic syndrome (HUS) is mixed, but current advice is to avoid their use.

Neurological involvement in HUS is relatively uncommon in adults.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Philippa Moore for her help and advice with respect to the microbiology of this case.

Footnotes

Contributors: JK authored the majority of the text and was involved in data acquisition. LS acquired and interpreted data and wrote the investigations section. RO and WD critically revised the article and gave final approval to its publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Public Health England. UK Government Website: news GOV.UK. [Online]. 2016. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/update-as-e-coli-o157-investigation-continues (accessed 23 Aug 2016).

- 2.Noris M, Remuzzi G. Hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005;16:1035–50. 10.1681/ASN.2004100861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell BP, Goldoft M, Griffin PM, et al. A multistate outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7-associated bloody diarrhea and hemolytic uremic syndrome from hamburgers. The Washington experience. JAMA 1994;272:1349 10.1001/jama.1994.03520170059036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eriksson KJ, Boyd SG, Tasker RC. Acute neurology and neurophysiology of haemolytic-uraemic syndrome. Arch Dis Child 2001;84:434–5. 10.1136/adc.84.5.434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hovius SE, Rietra PJ. Salmonella colitis clinically presenting as a pseudomembranous colitis. Neth J Surg 1982;34:81–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kendrick JB, Risbano M, Groshong SD, et al. A rare presentation of ischemic pseudomembranous colitis due to Escherichia coli O157:H7. Clin Infect Dis 2007;45:217–9. 10.1086/518990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pressly KB, Hill E, Shah KJ. Pseudomembranous colitis secondary to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). BMJ Case Rep 2016. 10.1136/bcr-2016-215225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bignardi GE. Risk factors for Clostridium difficile infection. J Hosp Infect 1998;40:1–15. 10.1016/S0195-6701(98)90019-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van den Berg RJ, Bruijnesteijn van Coppenraet LS, Gerritsen HJ, et al. Prospective multicenter evaluation of a new immunoassay and real-time PCR for rapid diagnosis of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in hospitalized patients. J Clin Microbiol 2005;43:5338–40. 10.1128/JCM.43.10.5338-5340.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrison DM, Tyrrell DL, Jewell LD. Colonic biopsy in verotoxin-induced hemorrhagic colitis and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). Am J Clin Pathol 1986;86:108–12. 10.1093/ajcp/86.1.108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richardson SE, Karmali MA, Becker LE, et al. The histopathology of the hemolytic uremic syndrome associated with verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli infections. Hum Pathol 1988;19:1102–8. 10.1016/S0046-8177(88)80093-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Proulx F, Turgeon JP, Delage G, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of antibiotic therapy for Escherichia coli O157:H7 enteritis. J Pediatr 1992;121:299–303. 10.1016/S0022-3476(05)81209-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freedman SB, Xie J, Neufeld MS, et al. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infection, antibiotics, and risk of developing hemolytic uremic syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2016;62:1251–8. 10.1093/cid/ciw099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menne J, Nitschke M, Stingele R, et al. Validation of treatment strategies for enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O104:h4 induced haemolytic uraemic syndrome: case-control study. BMJ 2012;345:e4565 10.1136/bmj.e4565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]