Abstract

Cystic retrorectal tumours are a very rare entity that pose a problem in differential diagnosis between congenital cyst and other lesions. We present a 49-year-old female patient presenting a perineal bulge which was discovered simulating a vaginal birth associated with prolapsed haemorrhoids grade IV. The interest of this case resides in the surgical indication of a big presacral cyst demonstrated via CT causing acute intense pain due to pelvic organ compression, as no emergent surgery management has been reported up to date.

Keywords: gastrointestinal surgery, general surgery

Background

Cystic retrorectal tumours are a very rare entity that pose a problem in differential diagnosis between congenital cyst and other lesions. Surgical resection is considered the best approach, since as much as malignant degeneration can appear up to 21% of cases with very poor prognosis.1 Definitive diagnosis is given by pathological examination of the surgical specimen.

An incidence between 0.00025 and 0.014 has been reported with a larger prevalence in women (female:male ratio 3:1). The differential diagnosis is wide and includes a congenital origin in most of cases and neurogenic, osseous or inflammatory origin.2 Congenital cystic lesions are the most common, and they represent up to 40% of retrorectal tumours. They are mainly benign and can be classified in dermoid cyst, epidermoid cyst, hamartoma, teratoma and enterogenic cyst.1 3

Most of benign retrorectal cysts are asymptomatic and are an incidental finding during imaging or rectal examinations. However, big masses can lead to symptoms related with neighbour organ compression such as constipation, abdominal pain or overflow urinary incontinence.4 To date, no retrorectal tumour requiring emergency surgery has been reported.

The diagnosis of these lesions is often an incidental finding during imaging examination due to other pathology. Although most are touchable by rectal examination, CT has been widely considered as the gold standard to establish extension and decide surgery approach. In the last few years, rectal contrast-enhanced pelvic MRI has become an important tool providing higher resolution and optimal assessment of relation with rectum, nerves and pelvic muscles. Nowadays, the role of needle biopsy is controversial. Most authors do not recommend it considering that it can favour secondary infection of cystic lesions and it does not allow to discard malignancy in solid lesions despite a negative result.1 3

Surgical approach is the best treatment option because definitive diagnosis is not given until histopathological examination of the specimen. In tumours smaller than 8 cm not reaching S3 level, transacral approach is preferred. However, transabdominal or combined approach is recommended in larger lesions extending above sacral promontory or when malignancy is suspected, since pelvic structures, vessels and nerves are better visualised.2 3 5

Case presentation

We present a 49-year-old female patient with severe intellectual disability and epilepsy who was admitted in the emergency room with 1-month history of psychomotor agitation. The patient had come 1 week earlier with no evidence of organic pathology after adjustment of psychiatric treatment. During urinary catheterisation, a perineal bulge was discovered simulating a full-term birth associated with prolapsed haemorrhoids grade IV. Physical examination confirmed an extrinsic compression of the posterior vaginal wall with initial signs of ischaemia (figure 1). Although no signs of sepsis were observed, blood analysis showed C reactive protein of 250 mg/L, creatine kinase of 6798 U/L and lactate of 15 mmol/L. A CT scan was performed showing a left ovarian mass of 10×7 cm and a presacral cyst of 10×17 cm displacing rectosigmoid colon and bladder anteroposteriorly and uterus and vagina anteriorly and extending above S1 level (figure 2). No infection of the cyst was suspected given that no signs of sepsis appeared and the cystic image on CT was homogeneous and without presence of gas.

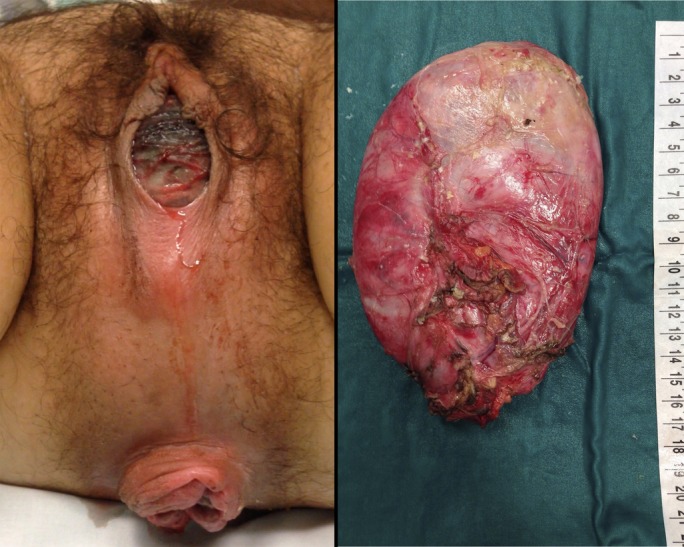

Figure 1.

On the left, perineal examination showing congested posterior vaginal wall prior to surgery. On the right, surgical specimen.

Figure 2.

CT imaging. On the left, axial slices showing displaced rectum (arrow) and uterus (asterisk). On the middle, coronal slice showing high extension up to iliac crests. On the right, sagittal slice showing relation with sacral bone and extension above the promontory. Ovarian cyst is not shown in this slice.

In light of the possibility of pelvic organ ischaemia, emergent surgery was indicated. Given that the tumour extended above S3 level, transabdominal approach combined with posterior approach if needed was decided.

Laparotomy revealed a retrorectal cyst displacing all pelvic organs. Mesorectal and rectovaginal wall dissection were performed. During enucleation, cyst perforation occurred obtaining ‘caseum’ content. After resection, vaginal wall viability was recovered slowly, and a pneumatic test was performed assuring rectal integrity.

The pathological examination showed a cystic lesion with an internal squamous epithelium layer compatible with epidermoid cyst.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient had a long postoperative recovery due to agitation and digestive intolerance. After almost 2 months of stay and given the persistent agitation and physical contention requirements, an electroconvulsive therapy was performed. Full recovery and discharge were achieved after 10 sessions.

Learning points.

The interest of this case resides in the surgical indication of a big presacral cyst demonstrated via CT causing acute intense pain due to pelvic organ compression, as no emergent surgery management has been reported up to date. As it is known, several approaches are available for resecting retrorectal tumours depending on tumour extension. In this case, pelvic ischaemia was caused by a big mass reaching above S3 level, so an anterior transabdominal approach was considered, since pelvic organs are much better visualised. Recovery after surgery was satisfactory, but early discharge was not possible due to preoperative comorbidity.

Footnotes

Contributors: EA-S and SP-S equally contributed in data collection and article writing. OCS and JP-G contributed in data acquisition.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Glasgow SC, Birnbaum EH, Lowney JK, et al. Retrorectal tumors: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Dis Colon Rectum 2005;48:1581–7. 10.1007/s10350-005-0048-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boscà A, Pous S, Artés MJ, et al. Tumours of the retrorectal space: management and outcome of a heterogeneous group of diseases. Colorectal Dis 2012;14:1418–23. 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.03016.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin C, Jin K, Lan H, et al. Surgical management of retrorectal tumors: a retrospective study of a 9-year experience in a single institution. Onco Targets Ther 2011;4:203–8. 10.2147/OTT.S25271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bullard Dunn K. Retrorectal tumors. Surg Clin North Am 2010;90:163–71. 10.1016/j.suc.2009.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Du F, Jin K, Hu X, et al. Surgical treatment of retrorectal tumors: a retrospective study of a ten-year experience in three institutions. Hepatogastroenterology 2012;59:1374–7. 10.5754/hge11686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]