Abstract

Propafenone is a Vaughan Williams class 1c antiarrhythmic medication widely used for treatment of arrhythmias. Although the long-term safety of propafenone use has not been established, it is commonly used for treatment of atrial fibrillation in patients with no structural heart disease. Propafenone is well known as pill-in-the-pocket treatment for its effect in terminating paroxysmal episodes of atrial fibrillation. Herein, we discuss an unusual adverse reaction to propafenone in a patient who presented with symptomatic bradycardia and hypotension. The aim of this article is to increase physician awareness for propafenone toxicity and its management, with a focused literature review on propafenone pharmacotherapy.

Keywords: Cardiovascular medicine, Pacing and electrophysiology, Drug interactions

Background

Propafenone is a Vaughan Williams class 1c antiarrhythmic medication that has a structural similarity to β-blockers with a local anaesthetic effect.1 2 It causes direct stabilisation on the myocardial membrane, resulting in an upstroke velocity (phase 0) reduction of the action potential.3 4 Propafenone causes reduction in fast inward potential by sodium channels, reduces spontaneous automaticity and prolongs the effective refractory period. It affects mainly the Purkinje fibres and to a smaller extent the myocardial fibres.3 Propafenone has a modest oral bioavailability in low doses that can increase more than threefold with higher doses.2 It has been recognised to be metabolised in two main patterns. Nearly 90% of patients metabolise propafenone into two active metabolites, 5-hydroxypropafenone by CYP2D6 (cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily D, polypeptide 6) and N-depropylpropafenone (norpropafenone) by CYP3A4 and CYP1A2. In these patients, its half-life is 2–10 hours. Less than 8% of patients have a defected 5-hydroxypropafenone metabolites pathway, leading to a delayed metabolism and a half-life of 10–32 hours. In these so-called slow metabolisers, increased norpropafenone metabolite levels can be more profound and facilitate propafenone toxicity.2 5

Case presentation

A 68-year-old white man with a history of hypertension and diet-controlled diabetes mellitus presented with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation that was treated with a combination of metoprolol tartrate 50 mg daily and propafenone 150 mg twice daily. He could not tolerate the β-blocker and propafenone combination because of symptomatic junctional bradycardia; therefore, metoprolol was discontinued. He continued to be treated with propafenone alone 150 mg three times a day. The patient was able to tolerate the medicine for a week with no complications or reported symptoms. His other medications included apixaban, hydrochlorothiazide and valsartan.

Seven days after the propafenone adjustment, the patient presented to the emergency department with an episode of cardiogenic syncope associated with light-headedness, nausea and vomiting. On evaluation in the emergency department, he was noted to have bradycardia (heart rate, 44 beats/min (bpm)) and hypotension (blood pressure, 82/57 mm Hg) with no evidence of orthostatic hypotension. The rest of his physical examination, including cardiac examination, was non-remarkable.

Investigations

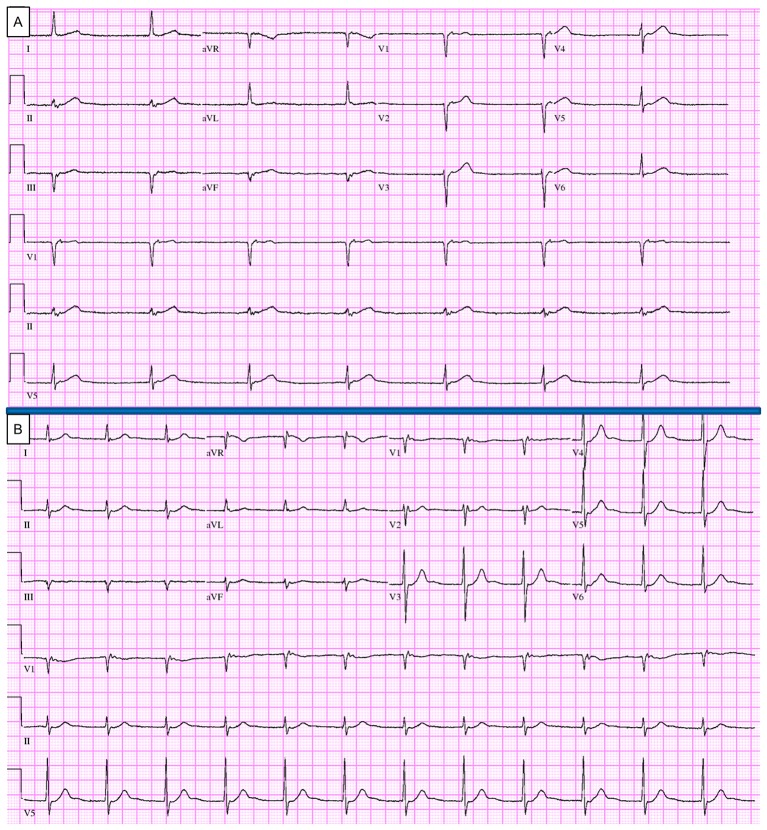

Electrocardiography revealed junctional bradycardia (figure 1A). Atropine 0.5 mg was given intravenously and repeated three times before the heart rate increased to 64 bpm. Repeat electrocardiography showed an accelerated junctional rhythm (figure 1B). The patient’s symptoms of light-headedness, nausea and vomiting persisted, along with hypotension, despite fluid resuscitation. Therefore, he was admitted to the intensive care unit and was administered dopamine at a drip rate of 5 mg/hour, which led to marked improvement in his blood pressure.

Figure 1.

(A) At the time of presentation, junctional bradycardia with heart rate of 34 beats/min. (B) After 2.5 mg atropine administration, accelerated junctional rhythm. The patient stayed symptomatic despite improved heart rate, mainly because of the junctional rhythm or the relatively low systolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg, or both. aVF, augmented vector foot; aVL, augmented vector left; aVR, augmented vector right.

All laboratory work-up and blood testing results were unremarkable. An infectious aetiological factor was ruled out. Lactate level was not elevated; troponin T was negative. CT angiography was negative for pulmonary embolism or dissection. Echocardiography identified no structural abnormalities in the heart, found normal left and right ventricular size and function, and found a left ventricular ejection fraction of 64%. Propafenone serum level was found to be 2.8 mcg/mL, indicating an excessive drug level and a potential toxic effect.

Treatment

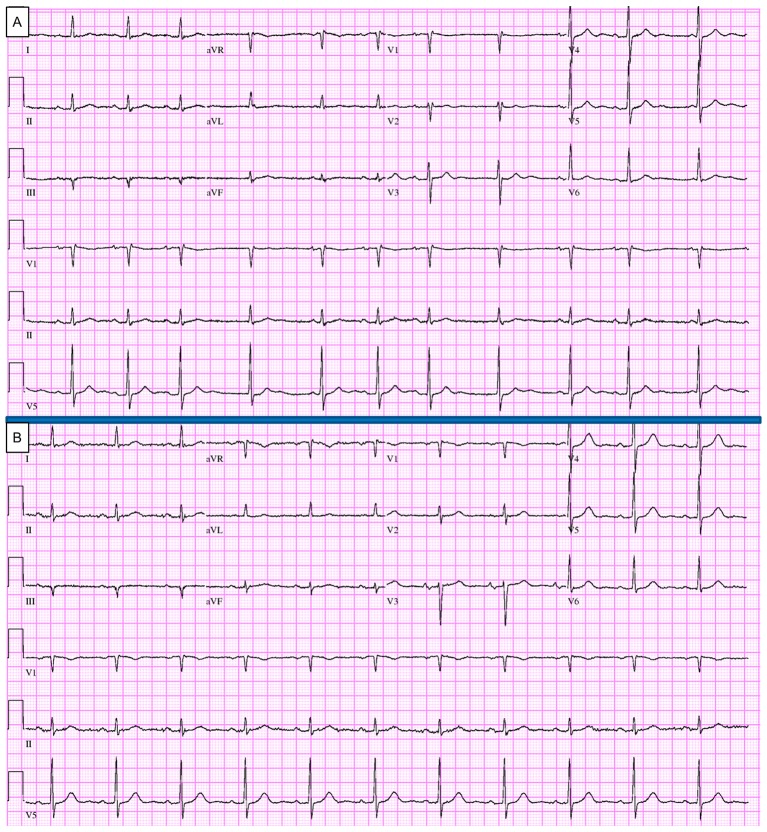

All medications were withheld, including propafenone, hydrochlorothiazide and valsartan. Eight hours after presentation in the emergency department, the patient expressed symptomatic improvement; his blood pressure was 114/89 mm Hg and heart rate was 72 bpm. Fluctuations in and out of sinus rhythm with competing junctional pacemaker and blocked premature atrial contractions were noted at that time (figure 2A). Overnight, the patient’s sinus rhythm converted completely to normal rhythm (figure 2B). The dopamine drip was tapered gradually, and the patient was discharged home successfully. Blood pressure medications were resumed gradually except for propafenone, the culprit in his presentation. The patient underwent an elective cryoablation of the pulmonary vein with a successful result.

Figure 2.

(A) Eight hours after admission, electrocardiography showing normal sinus rhythm and first-degree atrioventricular block alternating with competing junctional pacemaker and blocked premature atrial contractions. (B) At the time of discharge (38 hours after presentation and 40 hours after last propafenone dose), normal sinus rhythm with heart rate of 70 beats/min. aVF, augmented vector foot; aVL, augmented vector left; aVR, augmented vector right.

Outcome and follow-up

Follow-up in 1, 3 and 6 months showed no new symptoms or further syncopal attacks.

Discussion

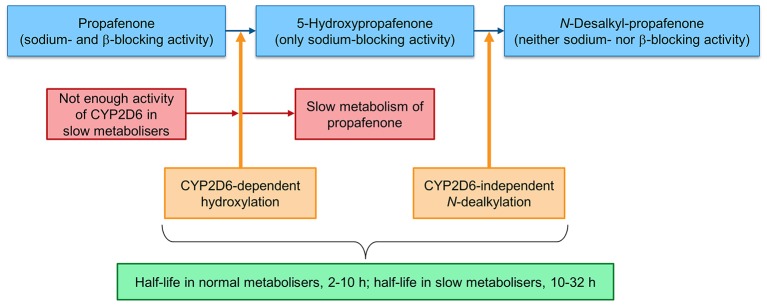

A class 1C antiarrhythmic medication, propafenone is widely used to treat atrial fibrillation and other arrhythmias. It is well known as a pill-in-the-pocket treatment for its effect in terminating arrhythmias, particularly paroxysmal episodes of atrial fibrillation.6 Propafenone has a sodium channel blockade activity that stabilises the myocardial cell membrane by prolonging the effective refractory period and increasing the diastolic excitability threshold.1 Propafenone also has a β-adrenergic blocking activity.2 In individuals who process propafenone normally, the drug undergoes extensive CYP2D6-dependent metabolism in the liver to form 5-hydroxypropafenone (5-hydroxy metabolites).7 The 5-hydroxy metabolites have potent sodium-blocking activity and no β-adrenergic activity. Therefore, individuals with normal metabolism (nearly 90% of the general public) have minimal β-blocking manifestation if they receive propafenone.2 Then, the 5-hydroxy metabolites will be converted to N-desalkyl-propafenone by a CYP2D6-independent dealkylation pathway (figure 3). N-desalkyl-propafenone has a weak sodium channel and β-blocking activity (inactive form). In individuals with intact CYP2D6 function, the propafenone half-life is 2–10 hours. Nearly 10% of the general population is genetically classified as slow metabolisers. This group has a defective CYP2D6-metabolising function.2 In these patients, the propafenone half-life is prolonged and can be up to 32 hours, making them vulnerable to propafenone toxicity secondary to the β-blockade and negative inotropic effect.2–4 Similarly, patients treated simultaneously with propafenone and a P450 enzyme inhibitor (such as certain antibiotics and antidepressants) can have iatrogenic propafenone toxicity. In both conditions, the serum level of 5-hydroxypropafenone metabolites is expected to be low because propafenone is not metabolised, resulting in disproportionate accumulation of the drug in the body.2 3 8 9

Figure 3.

The normal metabolism of propafenone via CYP2D6-mediated pathway in the liver (blue). In so-called slow metabolisers, propafenone converts to the hydroxy metabolites in a slower manner, leading to emergence of propafenone toxicity. Of note, difference is seen in propafenone half-life of slow metabolisers compared with normal metabolisers (green).

Propafenone toxicity has a wide range of clinical manifestations, both cardiac and extracardiac. Sinus bradycardia, rapid ventricular rates, nausea and dizziness are described in the literature to be commonly associated with propafenone toxicity.2 4 One of the main problems with propafenone is slowing atrial flutter or atrial tachycardia and facilitating one to one (1:1) AV conduction and rapid ventricular rates. Other cardiac manifestations that might be related to propafenone toxicity include junctional escape rhythm, sinoatrial and atrioventricular block, pauses, bundle branch block, transient hypotension and cardiac arrest.3 Syncope has been described in some literature as well.10

When propafenone toxicity is suspected, the medication must be discontinued immediately. Current and recent medication use should be reviewed carefully to rule out concomitant use of P450 inhibitors that may slow propafenone metabolism. Although not required to establish the diagnosis, serum tests of propafenone and 5-hydroxy metabolites are commercially available and can help confirm the diagnosis. A high propafenone serum level in conjugation with a low level of 5-hydroxy metabolites points to slow metaboliser status rather than drug overdose, in which both levels are expected to be high.2

Wagner et al 8 compared propafenone slow metabolisers with individuals having normal metabolism and found a significant difference in the serum level of the drug. Interestingly, these patients also were noted to be slow metabolisers of metoprolol and diltiazem, which have been attributed to competitive inhibition of CYP450 enzyme. This is probably the reason why our patient was not able to tolerate metoprolol initially, before propafenone was started.

Although genetic testing was not performed because of his clinical improvement after propafenone discontinuation, our patient was likely a slow propafenone metaboliser secondary to a CYP2D6 functional defect. Dysfunction of the enzyme explains his intolerance to the combination of metoprolol and propafenone because it likely resulted in a synergistic β-blockade effect. Although we did not test the serological levels of 5-hydroxy metabolites for this patient because of the high clinical suspicion of propafenone toxicity, the patient’s improvement with medication discontinuation was highly suggestive of the diagnosis.

Patient’s perspective.

The symptoms I had when I was sick were related to the medicine I started to take for the funny heart rhythm. My doctor told me not to take this medicine in the future as my body couldn’t handle it well. I underwent heart ablation, and since then I feel very good.

Learning points.

Propafenone undergoes extensive metabolism by hepatic cytochrome P450.

Propafenone level can be toxic when the drug is administered in conjugation with a CYP2D6 inhibitor.

Patients with a genetic CYP2D6 functional defect might be susceptible to propafenone toxicity.

Physicians should be aware of the clinical manifestations of propafenone toxicity.

Footnotes

Contributors: AAA authored the manuscript, designed the figures and conducted the literature review. YOG and COA interpreted the figures and reviewed the manuscript. FK carefully reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript prior to submission.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Amerini S, Bernabei R, Carbonin P, et al. Electrophysiological mechanism for the antiarrhythmic action of propafenone: a comparison with mexiletine. Br J Pharmacol 1988;95:1039–46. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11737.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mörike K, Magadum S, Mettang T, et al. Propafenone in a usual dose produces severe side-effects: the impact of genetically determined metabolic status on drug therapy. J Intern Med 1995;238:469–72. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1995.tb01225.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aronson JK, Meyler’s side effects of cardiovascular drugs. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kerns W, English B, Ford M. Propafenone overdose. Ann Emerg Med 1994;24:98–103. 10.1016/S0196-0644(94)70168-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Su Y, Liang BQ, Feng YL, et al. Assessment of 25 CYP2D6 alleles found in the Chinese population on propafenone metabolism in vitro. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2016;94:895–9. 10.1139/cjpp-2015-0509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Konety SH, Olshansky B. The "pill-in-the-pocket" approach to atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1150–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhou SF. Polymorphism of human cytochrome P450 2d6 and its clinical significance: part I. Clin Pharmacokinet 2009;48:689–723. 10.2165/11318030-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wagner F, Jähnchen E, Trenk D, et al. Severe complications of antianginal drug therapy in a patient identified as a poor metabolizer of metoprolol, propafenone, diltiazem, and sparteine. Klin Wochenschr 1987;65:1164–8. 10.1007/BF01733250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Slawson MH, Johnson-Davis KL. Quantitation of flecainide, mexiletine, Propafenone, and amiodarone in serum or plasma using liquid Chromatography-Tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Methods Mol Biol 2016;1383:11–19. 10.1007/978-1-4939-3252-8_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mansourati J, Khattar P. Benefit and concern about the "pill-in-the-pocket". J Med Liban 2013;61:101–4. 10.12816/0000410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]