Abstract

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a highly prevalent disease worldwide with many cases being metastasised to various organs during the time of initial presentation. Metastatic RCC to the breast is a rare entity and can mimic primary breast carcinoma. In this article, we present a 63-year-old Caucasian woman presented with a breast mass that was detected by screening mammography and found to have a biopsy proven grade-II clear RCC in the breast tissue. Despite the high incidence and prevalence of primary breast cancer, metastasis from extramammary should be suspected in patients with a prior history of other cancers. In this brief literature review, we also highlight the survival benefit from surgery and close follow-up in selected group of patients with metastatic, metachronous and solitary RCC.

Keywords: urological cancer, breast cancer, screening (oncology)

Background

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a very common malignancy with ~65 000 new case diagnosed annually in the USA.1 RCC commonly metastasise to the lungs, bone, liver, brain, and less commonly to ovaries and intestine.2 Only few case reports have described the involvement of breast tissue with RCC with estimated frequency of <0.1% of cases.2 Primary breast cancer is an extremely common malignancy in women, with an estimaedone in eight women in the USA develop breast cancer in their lifetime; however, metastases to the breast from extramammary tumours are generally considered rare.3–7

Breast metastases from RCC can occur in both synchronous (at same time of primary cancer diagnosis) and metachronous (metastases appear later in the disease course) patterns with correspondence to the primary tumour.6 7 Metastatic RCC to the breast tissue is rare; therefore, a high index of suspicion is needed to establish the diagnosis. This is especially true in patient with a prior history of nephrectomy or known history of RCC. The treatment and prognosis of these patients are different compared with primary breast cancer.3

Case presentation

A 63-year-old Caucasian woman with a medical history of hypertension and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus who was referred to our women's health clinic for evaluation of an abnormal routine screening mammography. Her past medical history was significant for right-sided clear RCC that was treated with radical nephrectomy 5 years prior to this presentation. At that time, patient had a vague abdominal pain and found to have a right kidney mass by CT. The kidney mass measured 5 cm in the biggest dimension and was localised to the right kidney upper pole with no evidence of perinephric spread, vascular invasion or distant metastasis. Tumour staging at that time revealed stage-1 RCC with T1bN0M0 (tumour size ~5 cm, no lymph nodes involvement or distal metastases) with estimated 5-year survival of 92.6%. Pathological grading of the tumour using Fuhrman nuclear grading of clear cell RCC revealed grade-II clear RCC (nucleus size ~17 µm with irregular shape and no nucleoli seen). Five-year survival was estimated at 84%. Risk score usingUniversity of California-Los Angeles' integrated staging system revealed low-risk tumour (localised, T1, Fuhrman nuclear grade-II and asymptomatic) with 5-year survival of 91.1%. After surgery, the patient underwent regular follow-up by uro-oncology department every 3 months for 1 year, then every 6 months afterwards with no evidence of local cancer recurrence on CT.

At the time of evaluation, the patient had no complaints and denied any self-detected breast mass. The patient’s body habitus was noticed for morbid obesity, with body mass index of 42. Vital signs at the time of evaluation were within normal limits. Breast examination revealed large breasts with no palpable masses, skin changes, tenderness or nipple discharge. The rest of physical examination was unremarkable. No lymphadenopathy was appreciated during physical examination.

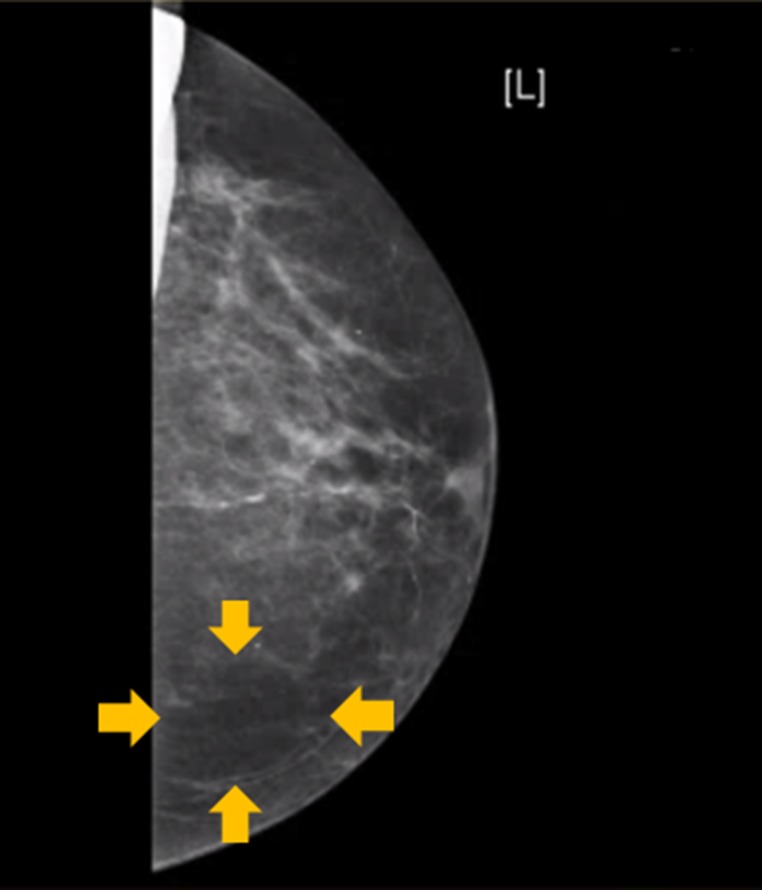

Breast mammography, which was performed as part of the patient’s annual screening, revealed a suspicious lesion in the left breast. The lesion was described as ~4×4 cm, dense, well-circumscribed mass between the lower quadrants of the left breast with no microcalcification or macrocalcification (figure 1). These findings are suspicious for tumours that can be of a benign or malignant nature, warranting further evaluation with more invasive testing.

Figure 1.

Screening mammography of the left breast showing a dense, well-circumscribed mass in the lower part of the breast. No microcalcifications or macrocalcifications are seen. These findings were highly suspicious for a breast tumour.

Investigations

Further evaluation of the breast lesion with imaging and biopsy was performed. Left breast ultrasonography with Doppler demonstrated a hypoechoic homogeneous nodule with peripheral vascularity at 6 o’ clock position, 6 cm from the left nipple measuring ~6×6×5 cm (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Ultrasonography of the left breast demonstrating a hypoechoic homogeneous nodule with peripheral vascularity at 6 o’ clock position. The nodule is nearly 6 cm from the left nipple and measuring nearly 6×6×5 cm.

A stereotactic, mammography-guided, 16-gauge core needle biopsy of the left breast was performed (figure 3A). Pathology result showed clear cells on H&E suggestive of metastatic RCC to the breast (figure 3B).

Figure 3.

(A) Stereotactic, mammography-guided, 16-gauge core needle biopsy of the left breast. The test was performed using a low dose X-ray and carried excellent outcomes mainly due to its low invasive nature in comparison to conventional breast biopsy. Usually no skin scar is left using this technique. (B) Pathology analysis from the core needle biopsy showing clear cell renal carcinoma, H&E x400 original magnifications.

Further staging of the disease is essential at this point. Therefore, CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis was performed and showed no evidence of masses or lymphadenopathy. A fluorodeoxyglucose, enhanced positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan did not reveal any active uptake lesions beside the known left breast mass.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnoses of a solitary breast mass include malignant and benign tumours. Primary breast malignancy includes ductal carcinoma, follicular carcinoma and carcinoma in situ. Metastasis to the breast from extramammary tumours such as melanoma, lung malignancy, lymphoma and leukaemia are the most frequently reported but still considered rare, with an estimated frequency of 0.4%–2% of total breast cancers.8 9

Treatment

After the diagnosis was confirmed with a tissue biopsy, and CT and FDG-PET scans showed no evidence of other metastatic lesions in any other areas of the body, the patient underwent a surgical excision of the mass. A left breast lumpectomy was performed and clear surgical margins were successfully obtained. Pathology analysis of the surgical specimen confirmed the diagnosis of RCC (figure 4A). Special staining was positive for vimentin with positive expression of antimembrane metalloendopeptidase antibody to cluster of differentiation-10 and surface membrane staining for RCC (figure 4B–D). Oestrogen receptors, cytokeratin-7 and S100 were negative. Therefore, the pathology analysis confirmed the diagnosis of clear RCC with metastasis to the breast. Pathological grading of the tumour using Fuhrman nuclear grading of clear cell RCC revealed grade-II clear RCC (nucleus size ~17 µm with irregular shape and no nucleoli seen). Selective sentinel axillary lymph nodes dissection was performed with no evidence of RCC on pathology. The patient had an uncomplicated surgical procedure.

Figure 4.

(A) Pathology analysis of the breast mass that was surgically obtained after lumpectomy showing clear cells suggestive of renal cell carcinoma, H&E x100 original magnification. Special staining for clear cell renal carcinoma shown in: (B) positive vimentin immunohistochemical stain, (C) positive expression of antimembrane metalloendopeptidase antibody to cluster of differentiation-10 and (D) immunohistochemical stain with detectable surface membrane staining for clear cell renal carcinoma, x100 original magnification.

The disease was staged as T1bNxM1 at this point. Despite the calculated Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) score for metastatic RCC in this patient was zero, suggesting a median survival of 20 months, metastatic RCC is generally known to be associated with poor prognosis and unfavourable outcomes.10 Thus, shared decision-making with the patient was attempted regarding the next step of the management. The patient preferred watchful waiting with close follow-up over further treatment options with immunotherapy.

Outcome and follow-up

A close follow-up plan was scheduled for the patient with a multidisciplinary team approach including primary care, breast and uro-oncology clinics. Follow-up CT continued every 3 months with no evidence of recurrent or metastatic disease detected during follow-up.

Discussion

In this case study, we highlight two important teaching points. First, screening mammography has been shown to be an effective imaging modality for early detection of primary breast malignancy; however, in rare circumstances like our case, it may detect secondary metastasis to the breast.11 Second, an isolated metastatic and metachronous RCC to the breast may be treated with surgical resection alone. In this circumstance, watchful waiting and a close follow-up is required. This is specially true if the metastatic disease detected early in the disease course with no other distant lesions.

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in women in the USA and other western industrialised countries.5–7 11 The incidence of breast cancer has increased dramatically in the last few decades to involve at least one out ofeight women in the USA.7 This increase in incidence and prevalence of breast cancerhas occurred predominately in primary breast malignancy. However, metastatic breast tumours from other cancers have remained rare, in particular metastatic RCC.12 13 Among nearly 65 000 new cases of RCC diagnosed annually in the USA, only 15 cases of RCC with metastases to the breast have been described in the literature.1 Our index case was found to have breast lesion on screening mammography, which warranted further diagnostic testing. Pathology analysis of the lesion revealed metastatic RCC that was initially treated with radical nephrectomy 5 years prior to the current presentation.

Reviewing the literature using PubMed central and MedLine searching, the phrases ‘Renal Cell Carcinoma’, ‘solitary breast metastasis’ and ‘secondary breast malignancy’ revealed only 15 sporadic cases that discussed the nature of this metastatic disease. In RCC, metastatic disease can occur in two forms: metachronous metastasis which occurs in a later course of the disease with no evidence of metastasis found at time of diagnosis (like in our case) or synchronous metastasis with functionally active metastatic disease at the time of initial diagnosis.14 15 Both types of metastases can occur in solitary or multiple forms. Thyavihally et al15 discussed 3 years and 5 years post metastatic lesion resection survival in RCC with metachronous solitary metastasis, which was found to be 58% and 35%, respectively. However, synchronous metastasis had a 3-year survival of only <20%. The cohort was conducted on 1863 patients treated for RCC between 1988 and 2001. Of these cases, 43 had solitary metastases to different locations in both synchronous and metachronous forms.15 Main locations of metastases included lungs, bone, liver and brain. A complete response to non-surgical treatment modalities was found in only <15% of cases, whereas surgical resection of the tumour was associated with better survival and outcomes. Therefore, aggressive surgical resection of both primary and metastatic lesions may be justified for this group of patients.3 4 12 13 15 Moreover, RCC has been shown to have an initial presentation as metastatic disease in nearly 23% of patients as shown in the study by Ritchie and De Kernion et al14 which described 25% of RCC survivals to develop metastatic disease within 5 years after nephrectomy. Although it is well known that patients with metastatic RCC have poor prognosis and a high relapse rate within 6 months, our patient continued to have negative scans and no evidence of relapse within 1 year of follow-up. This may suggest a role for surgical resection alone with close follow-up in patients with isolated metastases to the breast. This supports the previously described evidence to favour surgical resection in metastasised RCC to the bones and lungs.10 16

Systemic therapy for metastasised RCC is showing a promise with few types of immunotherapies have been Food and Drug Administration approved for the disease treatment.2 Also, stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (thermal ablation in particular) is currently the most studied treatment option for patients who are at high risk for surgical operations. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy is approved for localised RCC and has been shown to have favourable outcomes when compared with other modality of radiotherapy.17 Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy is currently under investigation for metastatic RCC treatment.18

The treatment approach in this rare case was associated with positive outcomes. However, it is important to highlight few special points that may not be applicable in other circumstances. First, our patient had a metachronous metastatic lesion that was detected by routine mammography screening. No other signs of active disease were detected beside the breast mass, as CT and FDG-PET scan showed no localised masses, and no metabolically active lesions, respectively. Therefore, the applicability of the same treatment modality with only surgical resection to patients who do not fall into this category may be disputable. Second, the RCC recurrence occurred in our index case 5 years after the initial cancer resection. Thus, the applicability of the same treatment strategy in patients present after longer or shorter duration from the initial cancer resection is unknown. Further case studies and research to better illustrate the benefits from surgical resection alone versus combined therapy are needed.

Patient’s perspective.

When my doctor called me to come to the office to discuss the results of my breast mammography, I was concerned about breast cancer because my mother died from this disease. I was scared of having mastectomy. Then I learned that the lump in my breast was a spread of the kidney cancer I had in the past. I am glad and thankful that I have no cancer recurrence on the follow up tests.

Learning points.

Breast metastasis of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a rare disease.

Mammography screening for breast cancer may coincidentally detect breast metastases of other tumours.

Surgical resection can be an effective treatment option for patients with isolated, metachronous and metastatic RCC to the breast.

Further case studies and research are needed to show long-term outcomes in patients undergoing surgical removal of secondary breast malignancy with or without systemic therapy.

Footnotes

Contributors: SMD and AAA authored the manuscript and conducted the literature review. AAA reviewed and interpreted the images and designed the figures. ARA and FHS critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript prior to submission.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Gandaglia G, Ravi P, Abdollah F, et al. Contemporary incidence and mortality rates of kidney cancer in the United States. Can Urol Assoc J 2014;8:247–52. 10.5489/cuaj.1760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choueiri TK, Motzer RJ. Systemic therapy for metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2017;376:354–66. 10.1056/NEJMra1601333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falco G, Buggi F, Sanna PA, et al. Breast metastases from a renal cell carcinoma. a case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep 2014;5:193–5. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2014.01.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahrous M, Al Morsy W, Al-Hujaily A, et al. Breast metastasis from renal cell carcinoma: rare initial presentation of disease recurrence after 5 years. J Breast Cancer 2012;15:244–7. 10.4048/jbc.2012.15.2.244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tarone RE. Breast Cancer trends among young women in the United States. Epidemiology 2006;17:588–90. 10.1097/01.ede.0000229195.98786.ee [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson WF, Katki HA, Rosenberg PS. Incidence of breast Cancer in the United States: current and future trends. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103:1397–402. 10.1093/jnci/djr257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeSantis C, Ma J, Bryan L, et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64:52–62. 10.3322/caac.21203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al Samaraee A, Khout H, Barakat T, et al. Breast metastasis from a melanoma. Ochsner J 2012;12:149–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moschetta M, Telegrafo M, Lucarelli NM, et al. Metastatic breast disease from cutaneous malignant melanoma. Int J Surg Case Rep 2014;5:34–6. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2013.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bullock A, McDermott DF, Atkins MB. Management of metastatic renal cell carcinoma in patients with poor prognosis. Cancer Manag Res 2010;2:123–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harding C, Pompei F, Burmistrov D, et al. Breast Cancer screening, incidence, and mortality across US counties. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1483–9. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alzaraa A, Vodovnik A, Montgomery H, et al. Breast metastasis from a renal cell Cancer. World J Surg Oncol 2007;5:25 10.1186/1477-7819-5-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Botticelli A, De Francesco GP, Di Stefano D. Breast metastasis from clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Ultrasound 2013;16:127–30. 10.1007/s40477-013-0026-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ritchie AW, deKernion JB. The natural history and clinical features of renal carcinoma. Semin Nephrol 1987;7:131–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thyavihally YB, Mahantshetty U, Chamarajanagar RS, et al. Management of renal cell carcinoma with solitary metastasis. World J Surg Oncol 2005;3:48 10.1186/1477-7819-3-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhat S. Role of surgery in advanced/metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Indian J Urol 2010;26:167–76. 10.4103/0970-1591.65381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell SP, Song DY, Pierorazio PM, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for the treatment of clinically localized renal cell carcinoma. J Oncol 2015;2015:1–6. 10.1155/2015/547143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheung P, Thibault I, Bjarnason GA. The emerging roles of stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2014;8:258–64. 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]