Abstract

A 52-year-old woman with a medical history of cervical and thyroid cancer, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, uncontrolled diabetes and heavy smoking was diagnosed with a new metastatic cholangiocarcinoma. While undergoing palliative chemotherapy, she developed dysarthria and left-sided weakness. Imaging studies showed multiple bilateral ischaemic strokes. On hospital days 2 and 5, she developed worsening neurological symptoms and imaging studies revealed new areas of ischaemia on respective days. Subsequent workup did not revealed a clear aetiology for the multiple ischaemic events and hypercoagulability studies were only significant for a mildly elevated serum D-dimer level. Although guidelines are unclear, full-dose anticoagulation with low molecular weight heparin was initiated given her high risk of stroke recurrence. She was discharged to acute rehabilitation but, within a month, she experienced complications of her malignant disease progression and a new pulmonary thromboembolism. The patient died soon after being discharged home with hospice care.

Keywords: Stroke, Cancer intervention, Prevention, Oncology, Therapeutic indications

Background

Patients with cancer have a substantial risk of ischaemic strokes, increasing their morbidity and mortality by more than twofold. This is a commonly recognised but poorly studied clinical situation, which represents a significant management challenge and brings together several medical fields. Ischaemic stroke is the second most common brain lesion in patients with cancer and, after an initial ischaemic stroke, accounts for 31% of all recurrent thromboembolic incidents in these patients.1 2 The pathophysiology of cancer-associated ischaemic stroke has been described, but the specific mechanisms linked to distinct patient and disease characteristics are not well known.3–6 There are no current diagnostic or therapeutic guidelines for the prevention and treatment of cancer-associated strokes. Initiation of anticoagulation therapy for secondary stroke prevention in such circumstance remains controversial and clinical management of these patients is challenging. We describe a case of multiple recurrent ischaemic strokes in a patient with cholangiocarcinoma. We present this case to emphasise the need for more studies that could shed light on the risk stratification and appropriate management of recurrent strokes in patients with a history of remote or current cancer. We also want to highlight the lack of current guidelines for the initiation of anticoagulation therapy for secondary stroke prevention in cancer-associated strokes.

Case presentation

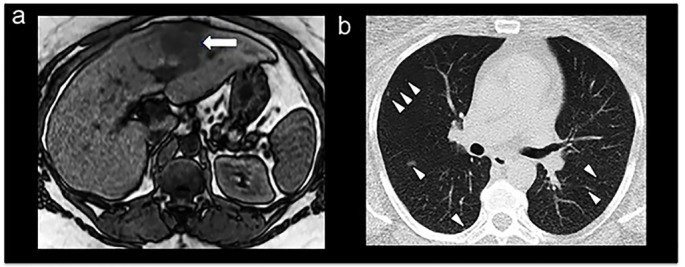

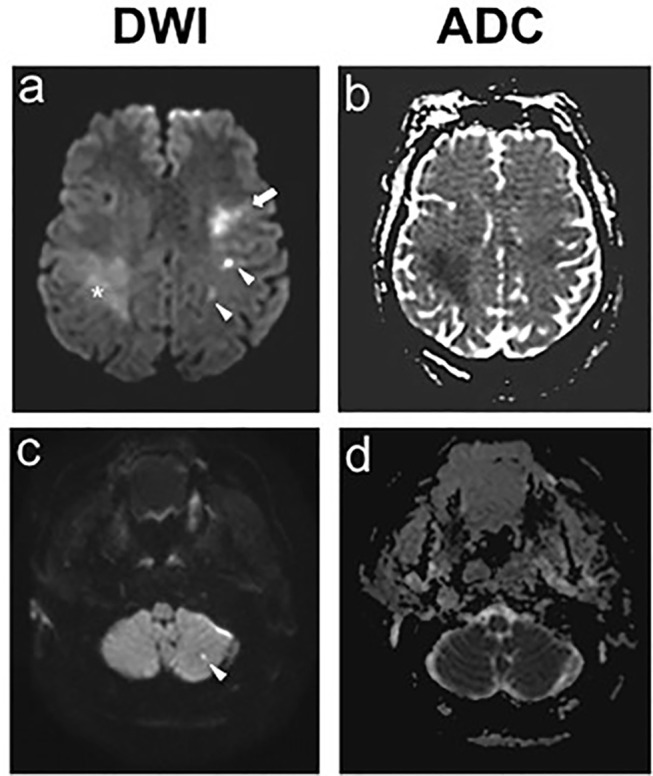

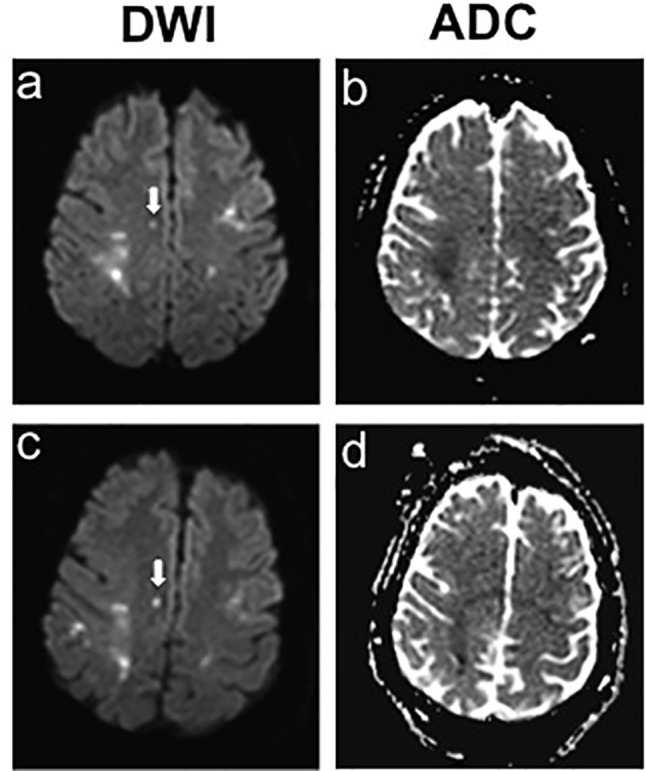

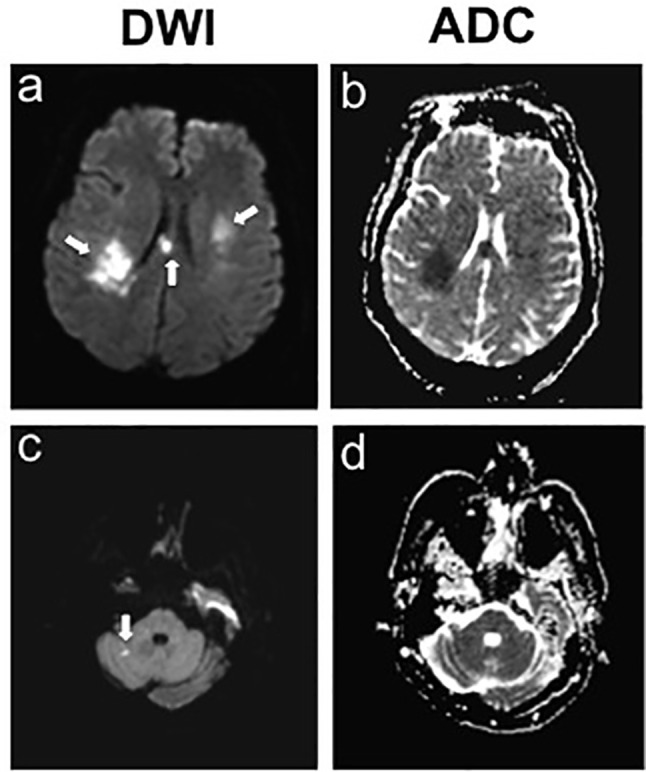

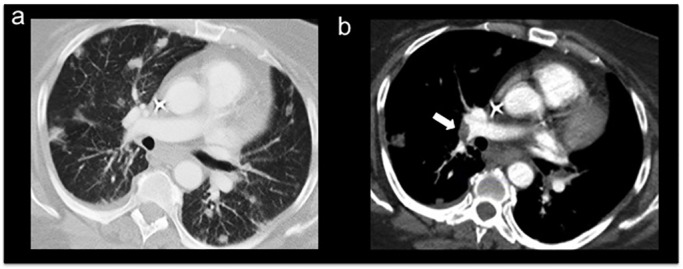

This is the case of a 52-year-old woman with a recently diagnosed liver mass with multiple bilateral metastatic pulmonary nodules (figure 1A,B). She had a history of cervical and thyroid cancer 10 and 4 years ago, respectively, both currently in remission. The malignancy was initially detected as a new unexpected liver finding on surveillance imaging for her cervical cancer history. MRI with MR cholangiopancreatography and pathology via CT-guided percutaneous core biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma. The patient also had a medical history of hypertension, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, asthma, morbid obesity, hypothyroidism, neuropathy and arthritis, as well as a 62 pack-years smoking history. The patient underwent systemic palliative chemotherapy with cisplatin and gemcitabine for 5 months, and 6 days after her eighth cycle of chemotherapy, she presented to the emergency department with altered mental status, sudden onset of left upper and lower extremities’ weakness and slurred speech for 1 day. The patient also described having mild shortness of breath for a few days and diffuse bilateral wheezing was noted during examination. The patient was not in acute respiratory distress; vital signs and oxygen saturation on room air were within normal limits during this admission. The patient had a medical history of asthma and received a combination of beta-adrenergic and anticholinergic bronchodilator (DuoNeb) which improved her symptoms. With regard to the neurological symptoms, the last known normal (LKN) time was determined as 7 hours prior to admission. A non-contrast head CT scan was unremarkable; however, brain MRI findings were consistent with acute multiple non-haemorrhagic strokes. These infarcts involved the right frontal and temporoparietal areas, in the vascular territory of the right middle cerebral artery bilaterally (figure 2A,B). Infarcts also involved the left cerebellum corresponding to the vascular distribution of the posteroinferior cerebellar artery (figure 2C,D). The patient was admitted to the neurology stroke service for stroke workup and poststroke care. On the second day of hospitalisation, she experienced agitation, worsening dysarthria and left-sided weakness. MRI studies showed a new small infarct in the deep white matter of the right hemisphere, specifically in the right parasagittal frontal lobe (figure 3). On hospital day 5, the patient re-experienced worsening dysarthria and increased weakness at the left upper and lower extremities. There was also sensory deficits to light touch and proprioception at the left side. A repeat brain MRI demonstrated a new stroke within the body of the corpus callosum and right cingulate gyrus (figure 4A,B), as well as the superior aspect of the right cerebellar hemisphere (figure 4C,D). When compared with the patient’s prior brain imaging studies, the remaining acute and subacute strokes were essentially stable in appearance. After this clinical event, the patient had a stable hospital stay until discharge to an acute rehabilitation centre.

Figure 1.

Non-contrast abdominal MRI showing a mass on the left liver lobe (arrow) as a typical hypointense lesion on a T1-weighted image (A). Non-contrast chest CT showing discrete multiple bilateral lung nodules at the time of diagnosis (B; arrowheads).

Figure 2.

Hospital day 1, brain MRI showed bilateral middle cerebral artery strokes (A,B) and left posterior inferior cerebellar artery strokes (C,D: ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; DWI, diffusion weighted imaging.

Figure 3.

Hospital day 2, brain MRI showed small newly developed strokes in the right parasagittal frontal lobe. ADC, apparent diffusion coefficients; DWI, diffusion weighted imaging.

Figure 4.

Hospital day 5, brain MRI showed two foci of new ischaemia within the body of the corpus and right cingulate gyrus, as well as the superior aspect of the right cerebellar hemisphere. DWI= diffusion weighted imaging; ADC= apparent diffusion coefficient.

Investigations

At the acute presentation and after the two episodes of sudden neurological deterioration, the patient underwent urgent non-contrast head CT and brain MRI studies. Initial tests were performed and showed that haemoglobin A1c was 6.8%, low-density lipoprotein was 100 mg/dL and high-density lipoprotein was 51 mg/dL. They also showed pancytopenia associated with the recent chemotherapy treatments and elevated alkaline phosphatase levels due to the underlying cholangiocarcinoma. Extensive workup to investigate the stroke aetiology was conducted, and the relevant findings are discussed below in relation to each differential diagnosis.

Differential diagnosis

Several differential diagnoses wereconsidered, as described in the following sections.

Embolic strokes due to cardiac aetiology

The patient had history of several major conventional vascular risk factors such as hypertension, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, heavy smoking and dyslipidaemia. Imaging studies confirmed recurrent acute ischaemic strokes in multiple vascular territories, suggestive of embolic or—less likely—hypotensive or watershed aetiologies. Workup was done to investigate a cardioembolic aetiology for the acute stroke: head and neck CT angiography with and without contrast was unremarkable. Continuous ECG did not reveal any concomitant acute myocardiac ischaemia or arrhythmias, and cardiac enzymes were unremarkable. A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) showed no atrial enlargement and no evidence of intracardiac thrombus or patent foramen ovale. However, there was moderate hypokinesis in the anterior septal wall with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 40%. This mild left ventricular systolic dysfunction was considered to be a result of the recent use of chemotherapeutic agents and less likely to be the predisposing source for thrombus formation. After discussion with cardiology team, no loop recorder was implanted at the moment given the patient’s cancer diagnosis, poor prognosis and immunocompromised state. Instead, an event monitor was to be considered prior to discharge for the purpose of long-term rhythm monitoring.

Embolic strokes due to infective endocarditis

Given the immunocompromised state of the patient secondary to recent chemotherapy, blood cultures, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C reactive protein (CRP) studies were obtained to address a suspicion of endocarditis. A high ESR of 45 mg/dL (normal range 0–20 mg/dL) and a high CRP of 1.52 mg/dL (normal <0.5 mg/dL) were found. There was one positive blood culture for Gram-positive cocci in clusters, coagulase negative, but subsequent blood cultures were negative which favoured the probability of a contaminated specimen. Throughout the hospital stay, there was no evidence of bacteraemia and no clinical findings sustained suspicion for endovascular infection.

In light of her advanced malignancy, non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE) was also considered as a manifestation of the cancer-associated hypercoagulability. In contrast to infectious endocarditis, in NBTE there is deposition of small, sterile and friable vegetations on valvular surfaces leading to a thrombogenic state and embolic strokes. Notably, no valve vegetations or murmur were reported in this patient on the TTE.4 7 8 But, the lesions on the heart valves in NBTE are commonly missed and transoesophageal echocardiography (TEE) has been shown to be more sensitive in detecting vegetations than TTE.7 The team considered conducting a TEE once the patient was in a more stable clinical condition, but this was not done due to comorbidities and high risk of bleeding. Early in the inpatient management, the patient had severe thrombocytopenia due to recent chemotherapy. Later, after the multiple recurrent episodes of acute ischaemic events, the patient was placed on full dose anticoagulation for secondary stroke prevention. The TEE was going to be pursued as outpatient, but after discharge the patient discontinued any interventions and opted for supportive care only. Since conducting a more sensitive TEE was not possible in this patient, the diagnosis of NBTE cannot be completely rule out.7

Brain metastasis in the setting of advanced cholangiocarcinoma

Notably, multiple, non-specific, left-sided hyperintensities were seen in the initial brain MRI fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR)images and, given the patient’s known advanced cancer state, these findings suggested the possibility of metastatic brain disease. For further investigation, a complete non-contrast and contrast brain MRI was conducted. This study confirmed the prior ischaemic findings, and the multiple areas of mild contrast enhancement observed were considered to be due to blood–brain barrier breakdown rather than brain metastases.

Ischaemic stroke associated with the chemotherapy agents

There is a likely relationship between ischaemic stroke and malignancy, and the risk elevates even higher in patients treated with chemotherapy. This has been reported in association with cisplatin-based chemotherapy and in some cases with gemcitabine. Our patient was undergoing a regimen combining these two medications and therefore there was a chance of ischaemic stroke as an adverse effect of the chemotherapy itself. Similar to published reports, the initial stroke developed within 1–2 weeks after the last chemotherapy session; however, it is not common to have multiple recurrent strokes linked to chemotherapy agents and a definitive proof of causality is difficult to establish.9 Although less likely, another possible aetiology was chemotherapy-induced thrombotic microangiopathy such as thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura related to gemcitabine exposure, but the patient did not have the clinical features indicative of this clinical scenario.10–12

Embolic source due to hypercoagulable state in the setting of remote and active malignancy

After the multiple recurrent ischaemic events, and in the setting of malignancy and obesity, hypercoagulable states were investigated. Main coagulation studies (prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and international normalised ratio) were within normal ranges. Duplex ultrasonogram of the lower extremities ruled out deep venous thrombosis (DVT) as the source of the embolic events, and notably the patient was undergoing DVT prophylaxis since admission. Extensive hypercoagulable workup was conducted and results for fibrinogen, antithrombin III, protein C, protein S, factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene mutation analysis, dilute Russell’s venom viper time screen, cardiolipins, antiphospholipid antibodies and heparin-induced antibodies were all found to be normal. The only significant finding was an elevated D-dimer level of 3.19 mg/dL (normal value <0.5 mg/dL). Similarly, a second D-dimer level was measured and found to be elevated at 5.7 mg/dL after the third recurrent stroke. Interestingly, several studies have reported elevated D-dimer levels in recurrent cancer-associated strokes and have suggested it as a biomarker of a hypercoagulable state and a predictor of the short-term risk of ischaemic strokes in cancer patients.13–20

In cancer-associated thrombosis, the Khorana score is the most validated method that helps to assess venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk in cancer outpatients receiving chemotherapy and to inform recommendation for thromboprophylaxis.21 22 The calculated Khorana score for our patient using baseline data at the time of chemotherapy was 1 point (body mass index >35 kg/m2) for an intermediate VTE risk of 1.8%–2.0% at 2.5 months. Our patient developed three ischaemic strokes and one VTE all within 6 months after initiation of chemotherapy. Of note, to the best of our knowledge, there is no published data on large cohort studies using this score for risk prediction of arterial events such as ischaemic strokes in patients with cancer.

Treatment

Following the first diagnosis of acute ischaemic stroke, the patient was stabilised clinically and was promptly initiated on the early key poststroke medical protocol according to national guidelines. The patient had a LKN time of more than 4.5 hours and also had pancytopenia with a low platelet count secondary to the recent chemotherapy treatments. Thrombolytic therapy was not appropriate, and she was admitted to a dedicated stroke unit for medical management. Treatment included blood pressure and glucose control, fluid management and swallowing assessment. Antihypertensives were withheld on day 1 of admission to facilitate permissible hypertension given a mild hypotensive state; they were then resumed to achieve moderate blood pressure control during the rest of the hospital course. She was also initiated antithrombotic therapy with aspirin and statin therapy, as well as inpatient DVT prophylaxis with subcutaneous heparin. After the third stroke, full-dose anticoagulation with therapeutic low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) was initiated (enoxaparin 120 mg twice a day subcutaneously). Although guidelines about anticoagulation for stroke prevention in patients with are unclear, this approach was initiated by consensus between neurology and haematology–oncology in view of the patient’s dramatic high-stroke recurrent risk. The possible hypercoagulable state due to the advanced malignancy and the potential for bleeding on anticoagulation were also discussed with the patient.

With regard to the metastatic cholangiocarcinoma, the patient’s most recent cycle of palliative chemotherapy was 6 days prior to the onset of the first neurological event, and further oncological regimen was put on hold until acute neurological issues were resolved. In general, the prognosis of patients with unresectable stage IV cholangiocarcinoma is poor, and therapies such as systemic chemotherapy have failed to show any significant increase in survival. Thus, the benefit of palliative measures should always be weighted against the potential side effects of the therapy. Prior to discharge, the goals of cancer care were discussed with the oncology team and the patient. It was recommended a multidisciplinary supportive care to achieve clinical stabilisation and a close follow-up with oncology as outpatient to decide about resuming palliative chemotherapy. Also, it was discussed additional palliative measures such as relief of symptoms, placement of a biliary stent to bypass obstructions and management of cholangitis to address future quality-of-life concerns due to possible progression of the malignancy.

Outcome and follow-up

After a 7-day hospitalisation, the patient was discharged to acute rehabilitation with instructions to receive continuous anticoagulation with enoxaparin (120 mg subcutaneously, twice a day). The patient followed up with haematology–oncology as an outpatient 2 weeks after discharge, and still had significant residual dysarthria and weakness in the left upper and lower extremities. Given her overall medical status, the patient decided not to resume the palliative chemotherapy treatments and to continue supportive care at the rehabilitation centre. One month later, the patient presented to the ED complaining of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and anorexia for 3 days. She was found to have sepsis secondary to acalculous cholecystitis, progression of the cancer and a complicated urinary tract infection related to long-term Foley catheterisation and chronic urinary retention. The patient also had shortness of breath and mild hypoxaemia, and subsequent workup found remarkable progression of her multiple lung metastases and a new onset pulmonary embolism (figure 5A,B); despite being prescribed anticoagulation therapy with enoxaparin as an outpatient. Due to her advanced cholangiocarcinoma, overall disease burden and multiple comorbidities, the patient was not a surgical candidate for cholecystectomy or for additional palliative chemotherapy. She opted for a cholecystostomy tube placement for symptomatic relief, and after achieving clinical stability, the patient and her family decided on her discharge home with hospice assistance and with the appropriate comfort measures. The patient died 2 days after being discharged.

Figure 5.

Contrast chest CT and pulmonary embolism protocol showing disease burden and significant progression of the multiple bilateral lung metastasis (A) and filling defect consistent with pulmonary embolism in the right lower lobe pulmonary artery (B).

Discussion

In this report, we present a patient who developed multiple early recurrent ischaemic strokes while undergoing chemotherapy for metastatic cholangiocarcinoma. As in this case, patients with active cancer may have multiple conventional vascular risk factors which could be the main underlying stroke aetiology.5 6 However, compared with the general population, patients with cancer are in a hypercoagulable state that increases their risk of events such as venous thromboembolism, arterial thrombosis, migratory superficial thrombophlebitis, NBTE and disseminated intravascular coagulation.7 23 24 In addition, besides coagulation disorders, other mechanisms such as direct cancer effect, paraneoplastic syndrome and complications of cancer treatment have been identified as possible causes of stroke in patients with cancer.1 25–27 In our patient, a number of factors pointed towards the probability of an embolic stroke aetiology due to cancer-associated thrombosis. These factors included the patient’s negative workup for the main traditional stroke risk factors, the presence of advanced-stage cancer, the occurrence of multiple early recurrent strokes in distinct vascular territories and the elevated D-dimer levels. In regard to D-dimer levels, several groups have studied D-dimer as a marker of a cancer-associated hypercoagulable state and in some cases high levels of D-dimer have been correlated with an increased risk of early recurrent events in patients with cancer after an initial acute ischaemic stroke.13–18 However, it is important to note that the predictive utility of this biomarker is not always this straightforward. This is because D-dimer levels could also be influenced by the advanced malignancy itself (such as large tumour burden, progression and metastasis without thrombosis), increased age, diabetes and other factors.14 15 28–31 Nonetheless, elevated D-dimer levels may be helpful in recognising ischaemic stroke as the initial presentation of an underlying malignancy in patients with cryptogenic stroke and multiterritorial brain lesions.32 33 That being said, in this patient, the suspicion of cancer-associated thrombosis was further strengthened when the patient also developed a new pulmonary embolism, a manifestation of hypercoagulability more frequently identified in patients with active cancer.

Further research is needed to better understand cancer-specific prothrombotic effects and how active inflammatory and immune response mechanisms may play a role in the pathogenesis of stroke.26 27 There are only a few large-scale epidemiological reports that systemically study the incidence, mechanism and appropriate treatment of recurrent stroke in patients with cancer. One of the most recent comprehensive studies determined that the majority of patients with cancer with recurrent thromboembolic events after ischaemic stroke had reached a metastatic disease stage. In addition, the most common histological tumour type was adenocarcinoma and the most common type of malignancy was lung cancer.1 Prior studies have determined that other common cancer types linked to recurrent stroke in patients are breast, gastrointestinal and gynaecological cancers.1 27 34 In the literature, we only found one reported case of recurrent ischaemic stroke in the setting of cholangiocarcinoma.35 Some studies found that the median time from diagnosis of underlying cancer to stroke was about 1 year, but in a number of patients with stroke could occur as early as 1 month or as late as several years after the cancer diagnosis. Interestingly, in some patients with stroke can be the initial sign of cancer, and approximately 84% of such patients had a second stroke within the following 4 months.1 2 32–34

Anticoagulation in high-risk vascular events is an established treatment. However, the use of risk-stratified thromboprophylaxis in patients with active malignancy as a strategy for the prevention of arterial, as well as venous, thromboembolic events is a less common intervention. Most clinical trials of cancer-associated thrombosis and the use of anticoagulation have focused on the treatment and prevention of cancer-associated venous thrombosis and clear guidelines have been established.36 37 Several large studies have focused on the risk assessment, safety and compliance with thromboprophylaxis for VTE in patients with cancer.38–42 However, it is uncertain how much these data can be extrapolated to guide clinical decision making for the use of anticoagulation in regards to arterial thrombotic events such as ischaemic strokes.

Controversies remain concerning the initiation of anticoagulation therapy and the optimal choice of medication for secondary stroke prevention in the setting of active malignancy. The goal of anticoagulation therapy in these patients would be to decrease their substantial risk of short-term stroke recurrence while also considering their risk of bleeding. However, there is not enough data to support the claim that early anticoagulation would be beneficial. One retrospective study suggested that treatment with LMWH may be more effective than warfarin for lowering the risk of stroke recurrence, but it was limited by a small sample size, confounding factors and a short study period.16 There is also an ongoing randomised phase I/II trial evaluating enoxaparin versus aspirin in patients with active cancer and first-ever acute ischaemic stroke to compare these treatments’ safety and efficacy in preventing recurrent thromboembolic events (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01763606). But, currently, the role of thromboprophylaxis for secondary stroke prevention in patients with active cancer is not addressed in current stroke or cancer treatment guidelines. Since this is an important evolving area of research, large-scale randomised prospective studies are needed to establish patient-specific and disease-specific diagnostic and treatment algorithms for acute and recurrent strokes in patients with cancer.

In closing, the interrelationship between ischaemic stroke and cancer is a complex one. As the life expectancy of the general population increases and the survival rate of patients with cancer improves, the coexistence of stroke and cancer in adult patients will continue to be common. This report seeks to highlight the intricacies of this correlation. It emphasises the relevance of establishing a distinct stroke aetiology on a patient-by-patient basis, especially when active malignancy is present. This, in turn, can have important implications for the prognosis, therapeutic management and prevention of recurrent stroke in patients with cancer.

Learning points.

Clinicians should remain alert for thromboembolic events (both arterial and venous) in patients with cancer as a possible cause of any clinical deterioration. Even though their risk is significantly increased with advanced cancer, delay in diagnosis is not uncommon and may negatively impact patient morbidity and mortality.

Identifying stroke aetiology in the setting of malignancy can be complex due to the presence of traditional cerebrovascular risk factors in many adult oncology patients, but this is crucial to defining treatment and prevention strategies.

Some studies have associated elevated D-dimer levels with a high risk of early recurrent ischaemic strokes in patients with cancer. Thus, it can be beneficial to consider D-dimer levels for risk stratification of recurrent events as part of the acute inpatient stroke management of certain patients with active cancer.

There are no current recommendations to support any benefit of early anticoagulation for secondary stroke prevention after acute stroke in patients with cancer. However, it should be considered if cancer-associated hypercoagulability is likely to be the main stroke aetiology.

Footnotes

Contributors: GAS-A: substantial contributions to the conceptualisation of the work, data acquisition and interpretation; drafting and revision of the work, final approval of the final version and analysis or interpretation of data; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. JZC: substantial contributions to the conceptualisation of the work, data acquisition and interpretation; revision of the work, approval of the final version; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. RKT: substantial contributions to the conceptualisation and design of the work and data supervision and interpretation; revision of the work, approval of the final version; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Navi BB, Singer S, Merkler AE, et al. . Recurrent thromboembolic events after ischemic stroke in patients with Cancer. Neurology 2014;83:26–33. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Navi BB, Reiner AS, Kamel H, et al. . Association between incident Cancer and subsequent stroke. Ann Neurol 2015;77:291–300. 10.1002/ana.24325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seok JM, Kim SG, Kim JW, et al. . Coagulopathy and embolic signal in Cancer patients with ischemic stroke. Ann Neurol 2010;68:n/a–9. 10.1002/ana.22050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schwarzbach CJ, Schaefer A, Ebert A, et al. . Stroke and Cancer: the importance of cancer-associated hypercoagulation as a possible stroke etiology. Stroke 2012;43:3029–34. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.658625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim SG, Hong JM, Kim HY, et al. . Ischemic stroke in cancer patients with and without conventional mechanisms: a multicenter study in Korea. Stroke 2010;41:798–801. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.571356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dearborn JL, Urrutia VC, Zeiler SR. Stroke and Cancer- A complicated relationship. J Neurol Transl Neurosci 2014;2:1039. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. el-Shami K, Griffiths E, Streiff M. Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis in cancer patients: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Oncologist 2007;12:518–23. 10.1634/theoncologist.12-5-518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bang OY, Seok JM, Kim SG, et al. . Ischemic stroke and cancer: stroke severely impacts cancer patients, while cancer increases the number of strokes. J Clin Neurol 2011;7:53–9. 10.3988/jcn.2011.7.2.53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li SH, Chen WH, Tang Y, et al. . Incidence of ischemic stroke post-chemotherapy: a retrospective review of 10,963 patients. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2006;108:150–6. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2005.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Govind Babu K, Bhat GR. Cancer-associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Ecancermedicalscience 2016;10:649 10.3332/ecancer.2016.649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Werner TL, Agarwal N, Carney HM, et al. . Management of cancer-associated thrombotic microangiopathy: what is the right approach? Am J Hematol 2007;82:295–8. 10.1002/ajh.20783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Blake-Haskins JA, Lechleider RJ, Kreitman RJ. Thrombotic microangiopathy with targeted Cancer agents. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17:5858–66. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee MJ, Chung JW, Ahn MJ, et al. . Hypercoagulability and mortality of patients with stroke and active cancer: the OASIS-CANCER study. J Stroke 2017;19:77–87. 10.5853/jos.2016.00570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nam KW, Kim CK, Kim TJ, et al. . D-dimer as a predictor of early neurologic deterioration in cryptogenic stroke with active cancer. Eur J Neurol 2017;24:205–11. 10.1111/ene.13184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nam KW, Kim CK, Kim TJ, et al. . Predictors of 30-day mortality and the risk of recurrent systemic thromboembolism in cancer patients suffering acute ischemic stroke. PLoS One 2017;12:e0172793 10.1371/journal.pone.0172793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jang H, Lee JJ, Lee MJ, et al. . Comparison of Enoxaparin and Warfarin for Secondary Prevention of Cancer-Associated Stroke. J Oncol 2015;2015:1–6. 10.1155/2015/502089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kono T, Ohtsuki T, Hosomi N, et al. . Cancer-associated ischemic stroke is associated with elevated D-dimer and fibrin degradation product levels in acute ischemic stroke with advanced Cancer. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2012;12:468–74. 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00796.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mytnik M, Stasko J. D-dimer, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, prothrombin fragments and protein C - role in prothrombotic state of colorectal cancer. Neoplasma 2011;58:235–8. 10.4149/neo_2011_03_235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lip GY, Chin BS, Blann AD. Cancer and the prothrombotic state. Lancet Oncol 2002;3:27–34. 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00619-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. De Cicco M. The prothrombotic state in cancer: pathogenic mechanisms. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2004;50:187–96. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2003.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, Culakova E, et al. . Development and validation of a predictive model for chemotherapy-associated thrombosis. Blood 2008;111:4902–7. 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Angelini D, Khorana AA. Risk Assessment scores for cancer-associated venous thromboembolic disease. Semin Thromb Hemost 2017. 10.1055/s-0036-1597281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bick RL. Cancer-associated thrombosis. N Engl J Med 2003;349:109–11. 10.1056/NEJMp030086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bick RL. Cancer-associated thrombosis: focus on extended therapy with dalteparin. J Support Oncol 2006;4:115–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Matijevic N, Wu KK. Hypercoagulable states and strokes. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2006;8:324–9. 10.1007/s11883-006-0011-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cestari DM, Weine DM, Panageas KS, et al. . Stroke in patients with cancer: incidence and etiology. Neurology 2004;62:2025–30. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000129912.56486.2B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang YY, Cordato D, Shen Q, et al. . Risk factor, pattern, etiology and outcome in ischemic stroke patients with cancer: a nested case-control study. Cerebrovasc Dis 2007;23:181–7. 10.1159/000097639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nwose EU, Richards RS, Jelinek HF, et al. . D-dimer identifies stages in the progression of diabetes mellitus from family history of diabetes to cardiovascular complications. Pathology 2007;39:252–7. 10.1080/00313020701230658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ebara S, Marumo M, Yamabata C, et al. . Inverse associations of HDL cholesterol and oxidized HDL with d-dimer in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Thromb Res 2017;155:12–15. 10.1016/j.thromres.2017.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tardy B, Tardy-Poncet B, Viallon A, et al. . Evaluation of D-dimer ELISA test in elderly patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Thromb Haemost 1998;79:38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Righini M, Goehring C, Bounameaux H, et al. . Effects of age on the performance of common diagnostic tests for pulmonary embolism. Am J Med 2000;109:357–61. 10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00493-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Goedee S, Naber A, Rovers JM, et al. . Ischaemic stroke as initial presentation of systemic malignancy. BMJ Case Rep 2014;2014:bcr2013202122 10.1136/bcr-2013-202122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bond LM, Skrobo D. Multiple embolic cerebral infarcts as the first manifestation of metastatic ovarian cancer. BMJ Case Rep 2015;2015:bcr2015211521 10.1136/bcr-2015-211521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Taccone FS, Jeangette SM, Blecic SA. First-ever stroke as initial presentation of systemic Cancer. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2008;17:169–74. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2008.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chaiyasit K, Wiwanitkit V. Ischemic stroke in a patient with cholangiocarcinoma: a case study. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2012;70:833 10.1590/S0004-282X2012001000019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lyman GH, Bohlke K, Falanga A; American Society of Clinical Oncology. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and treatment in patients with Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Oncol Pract 2015;11:e442–e444. 10.1200/JOP.2015.004473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Donnellan E, Khorana AA. Cancer and venous thromboembolic disease: a review. Oncologist 2017;22:199–207. 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Spyropoulos AC, McGinn T, Khorana AA. The use of weighted and scored risk assessment models for venous thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost 2012;108:1072–6. 10.1160/TH12-07-0508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rabinovich E, Bartholomew JR, Wilks ML, et al. . Centralizing care of cancer-associated thromboembolism: the Cleveland clinic experience. Thromb Res 2016;147:102–3. 10.1016/j.thromres.2016.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kuderer NM, Culakova E, Lyman GH, et al. . A validated risk score for venous thromboembolism is predictive of cancer progression and mortality. Oncologist 2016;21:861–7. 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Khorana AA, Yannicelli D, McCrae KR, et al. . Evaluation of US prescription patterns: are treatment guidelines for cancer-associated venous thromboembolism being followed? Thromb Res 2016;145:51–3. 10.1016/j.thromres.2016.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Khorana AA, Dalal M, Lin J, et al. . Incidence and predictors of venous thromboembolism (VTE) among ambulatory high-risk cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy in the United States. Cancer 2013;119:648–55. 10.1002/cncr.27772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]