Abstract

Acute pulmonary oedema is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in pregnant and postpartum women. We present an unusual case of near-fatal acute pulmonary oedema in a pregnant woman, which was attributed to the acute onset of neurogenic pulmonary oedema secondary to epileptic seizure activity. The patient required supportive management in the intensive care setting for a short period and subsequently made complete recovery with regular neurological follow-up arranged for the management of her epilepsy.

Background

Acute pulmonary oedema is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in pregnant and postpartum women. Untreated it can have devastating consequences for the women and her fetus including cardiorespiratory arrest and death. We present an unusual case of near-fatal acute pulmonary oedema in a pregnant woman, which was attributed to the acute onset of neurogenic pulmonary oedema (NPE) secondary to epileptic seizure activity. To the best of our knowledge, this unusual case is the first case of NPE as a result of seizures in a pregnant patient to be reported in the literature.

Case presentation

A 28-year-old Caucasian woman presented in her third pregnancy having had two previous spontaneous vaginal deliveries with no significant complications. She routinely booked for antenatal care at 8 weeks gestation with a body mass index of 24. Her medical history included endometriosis for which she had previously undergone two laparoscopies. She was generally fit and healthy and did not take any regular medications. She had no known drug allergies and was a non-smoker.

During the course of her pregnancy, she was investigated for recurrent episodes of shortness of breath during the early second trimester. Each time she was seen her symptoms spontaneously resolved within a short period of time and subsequent investigations failed to reveal any clear cause of her symptom. Given the lack of worsening or on-going symptoms, she had no formal respiratory follow-up arranged.

She was routinely admitted to the antenatal ward at 37+4 weeks gestation due to unstable lie for a stabilising induction of labour. During her admission, while resting in the ward, she developed acute shortness of breath and tachypnoea. On initial assessment, she was found to be disorientated with evidence of minimal fresh bleeding from her mouth. Her partner reported she had been sitting talking as normal and had fallen to the floor having risen from her bed. He thought she may have fallen on her face and bitten her tongue. He reported she had become a little vague and disorientated prior to the fall incident.

On assessment she was found to be tachypnoeac at 30 bpm, tachycardic with a heart rate of 125 bpm and had reduced oxygen saturations of 92% in room air. During the course of investigations over the next half hour, she was subsequently noted to have developed frothy pink sputum, bilateral expiratory wheeze and fine bi-basal crepitations. Her condition progressed, and she became acutely unwell with increasing tachypnoea and tachycardia. Her oxygen saturations were noted to have dropped and fluctuating between 50% and 60% on 100% oxygen.

Investigations

The initial arterial blood gas revealed alarming figures suggestive of type one respiratory failure with extreme hypoxia and oxygen saturations of 52% on room air with a partial pressure of oxygen of 3.94. Repeat arterial blood gas analysis while receiving 100% oxygen via a Hudson mask revealed oxygen saturations of 64% with a partial pressure of 4.8 kPa.

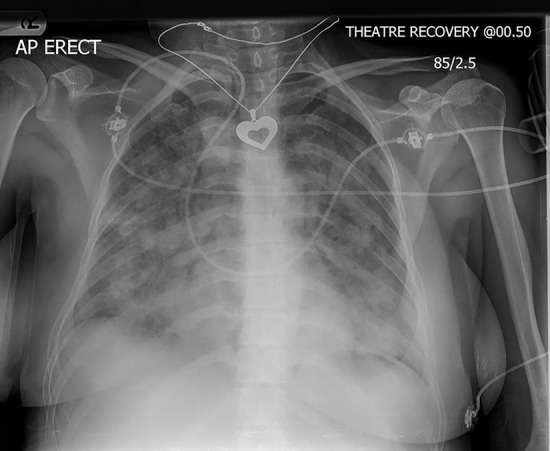

ECG demonstrated sinus tachycardia. Portable chest X-ray demonstrated diffuse fluffy white pulmonary infiltrates (figure 1). Following intubation and stabilisation, computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) was arranged. This confirmed extensive dense peri-hilar air space shadowing within both lungs. There was no pericardial or pleural effusion and no evidence of acute pulmonary thromboembolism. Aortic root was within normal limits.

Figure 1.

CXR showing diffuse bilateral pulmonary infiltrates. CXR, chest radiograph.

Differential diagnosis

The most common reason for an otherwise fit and healthy obstetric patient with no medical history to develop acute hypoxia with respiratory failure during the antenatal period is pulmonary embolism. While an amniotic fluid embolism may be considered, in the absence of rupture of membranes of labour and signs of labour this is extremely rare. Other important causes include sepsis, cardiomyopathy, aortic dissection and non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema or acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Having ruled pulmonary embolism (PE) and aortic dissection out by CTPA non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema secondary to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) was thought to be the most plausible explanation, although no clear trigger for the ARDS was initially apparent.

Treatment

A perimortem caesarean section was considered given concerns of potential catastrophic cardiorespiratory arrest. However, following intubation a small window was created to perform emergency caesarean section, during which time the patient remained haemodynamically critical but stable.

The patient was subsequently transferred and managed in the intensive care setting with high flow oxygen, diuretics and intravenous antibiotics and magnesium sulfate covering for sepsis and atypical pre-eclampsia among the differentials. She required inotropic support for the first 24 hours. As her condition improved and her oxygen requirements dropped, she was extubated 72 hours later. She remained stable and was subsequently stepped down from the intensive care setting 24 hours after extubation, day 4 postpartum.

Outcome and follow-up

During the course of her intensive care stay, various investigations and assessments were made. Cardiac echocardiogram and 24 hour Holter monitoring were essentially normal and thus cardiac causes were ruled out. There was no convincing evidence of pre-eclampsia (PET) on blood pressure observations or her blood and urine parameters. There was no convincing evidence of consolidation or chest sepsis and all microbiology investigations including blood cultures, sputum culture, Klebsiella, Legionella antigen, midstream urine sample (MSU), placental swabs and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) screen were negative, ruling out infection and sepsis as a likely cause.

She self-discharged home on day 9 postcaesarean section, with no evidence of any on-going respiratory dysfunction and a normal chest X-ray.

Prior to discharge, a neurologist was involved given the vague history that she may suffer with absence seizures and may also have had a seizure episode prior to the onset of the respiratory collapse. NPE was thus hypothesised as a potential explanation. Given the strong history of petit mal seizures, she was started on levetiracetam 1 g two times a day prior to discharge. Subsequent EEG studies, which were completed 6 weeks postpartum, reported idiopathic generalised epilepsy. Her epilepsy was subsequently clinically confirmed 2 weeks later when the patient was admitted via the emergency department having experienced full blown grand-mal epileptic seizures. Her antiepileptic medications were subsequently reviewed and optimised with regular neurological follow-up arranged.

Discussion

While pulmonary oedema is uncommon in pregnancy (0.08–0.5%),1 2 it is associated with significant morbidity and mortality if not recognised and treated promptly as highlighted repeatedly in previous confidential enquiries into maternal deaths.3 The use of tocolytic agents, cardiac disease, pre-eclampsia and iatrogenic fluid overload are well recognised aetiological factors of pulmonary oedema in pregnancy.3 The physiological changes associated with pregnancy, changes in hydrostatic pressures, colloid osmotic pressures and increased vascular permeability may all predispose pregnant women to develop acute pulmonary oedema.4 The ultimate extent to which a pregnant patient may compensate will depend on her cardiovascular reserve and the extent of the underlying disease burden.

NPE was first described by Shanahan5 in 1908. It is a rare but increasingly recognised complication of acute neurological injury with a reported prevalence between 2% and 8%.6 Its true prevalence is thought to be significantly greater but difficult to assess due to its poor recognition and diagnosis. The most common reported triggers of NPE are cerebral haemorrhage, trauma and epileptic seizures. The pathophysiology of NPE remains poorly understood. Theories suggest sudden increases in intracranial pressures leads to ischaemia effecting trigger zones causing a surge in centrally mediated sympathetic over-activity.6 In turn, there are associated triggers leading to pulmonary vascular changes, injury to capillary endothelium leading, fluid accumulation in the alveolar airspaces and intraalveolar haemorrhage.7

NPE most commonly occurs within minutes to hours of an acute neurological insult,6 but has also been reported in a delayed form up to 24 hours post the original insult.8 It is a diagnosis of exclusion once cardiogenic oedema and other pulmonary insults have been ruled out. Rapid progression to respiratory failure is one of the defining characteristics of NPE. As was the case in this patient, tachypneoa, tachycardia and central cyanosis tend to present. The presence of pink frothy sputum is one of the hallmarks of NPE.9 Chest radiograph characteristically shows diffuse bilateral infiltrates.

NPE mimics ARDS, with similar clinical presentation and radiological features but has distinctly different pathophysiology.6 It is associated with a high mortality rate of over 50%; however, this varies according to the underlying neurological insult rather than the acute respiratory compromise.6 The mainstay of treatment in the acute event is supportive including oxygenation, diuretics and inotropic support where required, with secondary management of the triggering neurological insult as appropriate. While the onset of profound hypoxia can be very abrupt, rapid resolution of symptoms in conjunction with rapid clearing of abnormalities on the chest X-ray is again indicative of the diagnosis.9

Neurological causes remain the third most common cause for maternal mortality from indirect causes.3 Epilepsy accounts for a significant number of these deaths with poorly controlled epilepsy, the main contributory risk factor.10 Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) is found to be the major cause of death in these patients.3 10 There is also increasing evidence to suggest that the incidence of NPE is far more prevalent than previously thought,9 and it may be an important aetiological factor for SUDEP.11–13 It is thus important that clinicians are aware of the clinical phenomena of NPE and suspect it in the differential diagnosis when presented with any patient who has a history of epilepsy or has suffered a neurological insult and subsequently develops unexplained acute respiratory compromise.

Implications of the gravid uterus, the physiological changes of pregnancy and considerations for the well-being and timely delivery of the fetus all add to the complexity of acute management of such potentially catastrophic conditions. To the best of our knowledge, this unusual case is the first case of NPE as a result of seizures in a pregnant patient to be reported in the literature. From time to time, clinicians will be challenged by complications from previously undiagnosed medical conditions. A systematic approach and early involvement of the multidisciplinary team is crucial to achieve good outcomes and reduce morbidity and mortality.

Patient's perspective.

I am grateful for all the kindness and care that was given to me by all the many members of the team. It has been a particularly difficult time for me and my family and we hope that sharing our case will help doctors to help other patients like myself in future.

Learning points.

Neurogenic pulmonary oedema is a recognised complication of epilepsy and other neurological insults.

Clinical staff should consider the diagnosis of NPE in any patient with a background history of neurological disease, in particular, epilepsy that suddenly develops profound hypoxia and respiratory compromise.

Clinical staff need to be trained in the early recognition and systematic management of acute respiratory compromise.

Early involvement of the multidisciplinary team is crucial to achieve good outcomes in the acutely unwell pregnant patient.

Footnotes

Contributors: HF and SV conceived the idea, and HF drafted the manuscript. SV and ES involved in overall supervision and advised on the drafting of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Sciscone AC, Ivester T, Largoza M, et al. Acute pulmonary edema in pregnancy. Obstet Gynaecol 2003;101:511–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poggi SH, Barr S, Cannum R, et al. Risk factors for pulmonary edema in triplet pregnancies. J Perinatol 2003;23:462–5. 10.1038/sj.jp.7210968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knight M, Tuffnell D, Kenyon S, et al. on behalf of MBRRACE-UK. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care—surveillance of maternal deaths in the UK 2011–13 and lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2009–13. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford, 2015. https//www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk/reports [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dennis AT, Solnordal BC. Acute pulmonary oedema in pregnancy. Aneasthesia 2012;67:646–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shanahan WT. Acute pulmonary edema as a complication of epileptic seizures. N Y Med J 1908;87:54–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Busl KM, Bleck TP. Neurogenic pulmonary edema. Crit Care Med 2015;43:1710–15. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao H, Lin G, Shi M, et al. The mechanism of neurogenic pulmonary edema in epilepsy. J Physiol Sci 2014;64:1880–6546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidson DL, Chawla LS, Selassie L, et al. Neurogenic pulmonary edema: successful treatment with IV phentolamie. Chest 2012;121:793–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fontes RB, Aguiar PH, Zanetti MV, et al. Acute neurogenic pulmonary edema: case reports and literature review. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 2003;15:144–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. Epilepsy in pregnancy. RCOG Greentop Guideline no. 68. London 2016. https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/guidelines/gtg68.

- 11.Rose S, Wu S, Jiang A, et al. Neurogenic pulmonary edema: an etiological factor for SUDEP? Epilepsy Behav 2015;52(Pt A):76–7. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Surges R, Thijs RD, Tan HL, et al Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: risk factors and potential pathomechanisms. Nat Rev Neurol 2009;5:1759–4758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Terrence CF, Rao GR, Perper JA. Neurogenic pulmonary edema in unexpected, unexplained death of epileptic patients. Ann Neurol 1981;9:458–64. 10.1002/ana.410090508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]