Abstract

Endarteritis is a major complication in patients with patent ductus arteriosus, causing significant morbidity and mortality. We report an adult patient with asymptomatic patent ductus arteriosus and endarteritis involving the main pulmonary artery and secondary infective spondylodiscitis at the L5–S1 intervertebral disc caused by Abiotrophia defectiva. A. defectiva, commonly referred to as nutritionally variant streptococci, cannot be identified easily by conventional blood culture techniques from clinical specimens. Its isolation was confirmed by 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing. The patient was successfully managed with a combination of penicillin G and gentamicin, pending surgical repair of the patent ductus arteriosus.

Keywords: Cardiovascular medicine, Infectious diseases, Bone and joint infections

Background

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is the third most common congenital cardiac anomaly with an incidence of one in 2000 live births.1 Campbell studied the natural history and progression of PDA and reported that 34% of the patients do not survive beyond 40 years of age and 61% beyond 60 years, with the the most common causes of mortality being congestive cardiac failure, infective endocarditis or pulmonary arterial hypertension.2 The prompt and accurate identification of the pathogen is essential for successful treatment of infective endocarditis. Abiotrophia defectiva, previously referred to as nutritionally variant streptococcus (NVS), has been increasingly implicated in endocarditis among patients with pre-existing cardiac disease.3–5 We report a case of infective endarteritis and infective spondylodiscitis secondary to bacteraemia caused by A. defectiva in an adult patient with asymptomatic PDA.

Case presentation

A 54-year-old female with asymptomatic PDA, which was diagnosed during a general medical check-up presented to our outpatient clinic with fever and low back pain for a duration of 6 weeks. The fever was high grade and associated with chills and the progressively worsening back pain was restricting her routine activities. She had visited multiple general practitioners, who had treated her with short courses of antibiotics (cefixime and azithromycin for 1 week) and analgesics, but with no improvement in her symptoms. She did not have any other comorbid illnesses.

On clinical examination she was pale, febrile (39.5°C) and had tachycardia (110 beats/min) with no peripheral signs of subacute bacterial endocarditis. Physical examination revealed a grade 4 continuous murmur in the upper left sternal border. There were no signs of cardiac failure.

Investigations

Laboratory investigations revealed anaemia with a haemoglobin level of 7.9 g/dL, a white cell count of 11.8×103/µL, normal serum creatine (1.31 mg%) and normal albumin (3.9 g/dL).

All four blood cultures obtained prior to initiation of antibiotics were flagged positive within 10 hours in the automated BacT/ALERT (Biomerieux, Durham, North Carolina) blood culture system. Microscopy revealed Gram-positive cocci in short chains. Fine alpha haemolytic colonies resembling colonies of enterococci were seen on sheep blood agar after overnight incubation. The colonies were catalase negative, showed no esculin hydrolysis or growth on MacConkey agar and were susceptible to penicillin, ceftriaxone and vancomycin but resistant to erythromycin by dilution method (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines). The Vitek 2 COMPACT automated system (Biomerieux) identified the organism to be Globicatella sanguinis (99% probability) based on biochemical characteristics. However the 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequencing identified it as A. defectiva.

Testing for the presence of 16S rRNA is not the routine standard of care in our institution; however, as the patient had a clinical diagnosis of infective endocarditis with the organism isolated in four different cultures, it was vital to identify the organism. Molecular methods are known for their high sensitivity and specificity, with rapid identification and precision.6 We recommend the use of sequencing by repeated isolation of an organism which will further accurately guide the choice of therapy.

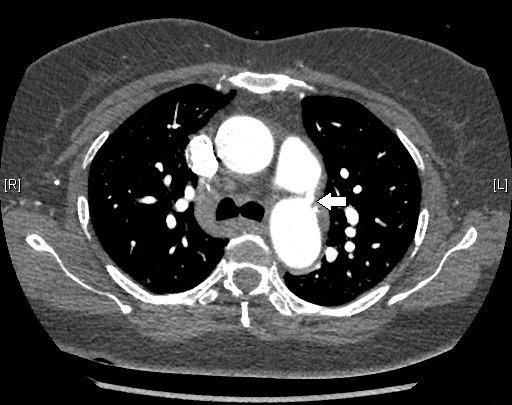

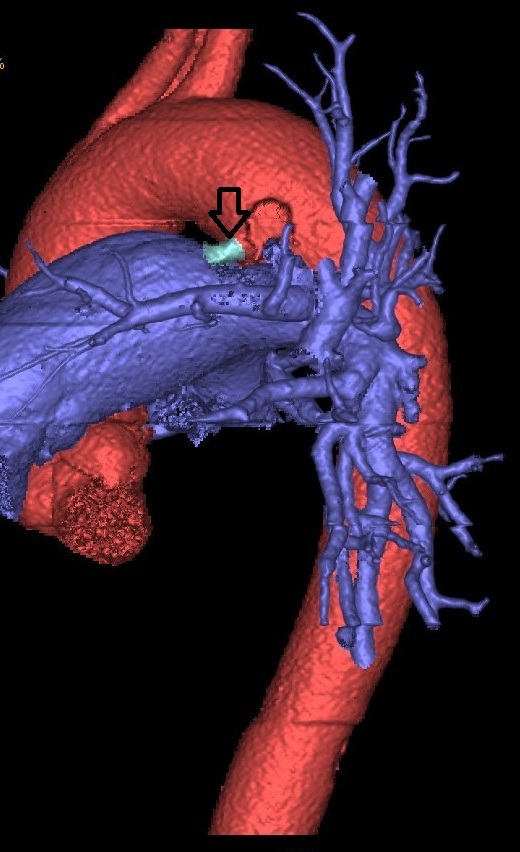

A transoesophageal echo revealed mild wall thickening of the main pulmonary artery at the site of PDA. The differential diagnosis for wall thickening in PDA is repeated trauma from the shunt on the wall causing remodelling of the muscular wall of the artery, endarteritis, mycotic aneurysm or a precursor lesion for the development of pulmonary arterial hypertension. In this case, with repeated isolation of the organism, the thickening is likely to be due to infective endarteritis. Contrast-enhanced CT of the heart with reconstruction revealed no intracardiac vegetations or abscesses (figures 1 and 2). MRI of the lumbosacral spine revealed altered signal intensity along the contiguous end plates of L5–S1, with para-vertebral oedema suggestive of infective spondylodiscitis (figure 3). This finding along with fever and positive blood cultures fulfilled the criteria for bacterial endarteritis.

Figure 1.

CT scan of the heart confirming the presence of patent ductus arteriosus in the patient.

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional reconstruction image of patent ductus arteriosus.

Figure 3.

Infective spondylodiscitis at the L5–S1 vertebral level.

Treatment

The patient was initiated on intravenous penicillin G along with gentamicin. The course in the hospital was uneventful and surgical repair of PDA was planned after 6 weeks of antibiotic treatment.

Discussion

The earliest reported case series on congenital cardiac lesions in the year 1914 by Hamilton and Abbot7 described the occurrence of pulmonary endarteritis in patients with PDA. The proposed mechanisms include trauma to the vascular endothelium by the high turbulence of blood flow from the aorta. Many reported cases in literature are significant for their adverse outcomes.8–12

A. defectiva is a part of the normal flora of human mucosal surfaces lining the intestinal and genitourinary tracts.13 It is implicated as a causative agent in various infections like osteomyelitis, sinusitis, corneal ulcers and abscesses, and life-threatening endocarditis.14 Based on 16S rRNA sequencing, it was identified as a separate genus Abiotrophia, which is distinct from the genus Streptococcus. 15 Conventional blood culture methods could not isolate these organisms because of their highly specific nutritional requirements. However, with the advent of automated blood culture systems endowed with rich nutritional supplements, the isolation and identification of these organisms have become increasingly possible.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) is increasingly being used in many laboratories for identification of organisms. In a study evaluating the performance of MALDI-TOF MS for the identification of Gram-positive organisms, the system correctly identified around 99% of the isolates to the genus level.16 Schulthess et al 16 have proposed an algorithm which could potentially be put to use in laboratories. NVSs have poor representation in the database, and increasing isolation of these organisms might lead to improvement of the database and advance the utility of the test.

Jayakeerthi and Kanungo17 reported a case of PDA with infective endocarditis caused by A. defectiva. 17 Identification was confirmed by enhanced growth on pyridoxal enriched medium and inability to grow on sheep blood agar without Streptococcus aureus streak.

The case we report highlights the combination of a rare pathology and an unusual pathogen for endarteritis. The source of the infection is possibly from the oral cavity. There is a great need for accurate identification using molecular methods when rare pathogens are involved. Although the clinical management would not have differed considerably in this case, if we had relied on the Vitek identification of G sanguinis, its sufficiency cannot be taken for granted. There is a 91.59% sequence similarity between both these organisms. The 8.41% difference could not be detected by the Vitek 2 system.

A study by Senn et al 18 on the clinical manifestations of Abiotrophia and Granulicatella revealed that the infections caused by Abiotrophia were more commonly seen in immunocompetent individuals and that treatment failure, relapse and mortality rates are higher in infections caused by A. defectiva than Granulicatella.

The isolate obtained from the patient was susceptible to penicillin and hence she was initiated on intravenous penicillin G 24 million units in four divided doses and gentamicin at 3 mg/kg for 2 weeks. The plan was to continue therapy for 6 weeks in view of infective spondylodiscitis, following which she was to undergo surgical repair of PDA.19 She was afebrile at discharge and showed significant clinical recovery.

Learning points.

Infective endocarditis is a complication of patent ductus arteriosus that is known to cause significant morbidity and mortality.

Abiotrophia defectiva is a potential pathogen that is known to cause serious infection in human beings.

The need for molecular methods for correct identification of rare pathogens cannot be overemphasised.

Treatment failure and relapses in Abiotrophia species are common and hence require administration of appropriate antibiotics for longer duration with close monitoring of the clinical outcome.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Aparna Irodi for radiodiagnosis and Dr V Balaji for help with the microbiology tests.

Footnotes

Contributors: ATM: involved in conceptualisation, acquisition of data, data analysis and writing of the case report, and is the guarantor. SKP: involved in data analysis and writing of the case report. JD: involved in writing of the case report. SS: involved in critical revision of the case report and its approval for submission.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Wiyono SA, Witsenburg M, de Jaegere PP, et al. Patent ductus arteriosus in adults: case report and review illustrating the spectrum of the disease. Neth Heart J 2008;16:255–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Campbell M. Natural history of persistent ductus arteriosus. Br Heart J 1968;30:4–13. 10.1136/hrt.30.1.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baroz F, Clément P, Levy M, et al. [Abiotrophia defectiva: an unusual cause of endocarditis]. Rev Med Suisse 2016;12:1242–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pinkney JA, Nagassar RP, Roye-Green KJ, et al. Abiotrophia defectiva endocarditis. BMJ Case Rep 2014. 10.1136/bcr-2014-207361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kalavakunta JK, Davenport DS, Tokala H, et al. Destructive Abiotrophia defectiva endocarditis. J Heart Valve Dis 2011;20:111–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burd EM. Validation of laboratory-developed molecular assays for infectious diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev 2010;23:550–76. 10.1128/CMR.00074-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Manges M. Patent ductus arteriosus with infective pulmonary endarteritis. Trans Am Climatol Clin Assoc 1916;32:313–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Matsukuma S, Eishi K, Hashizume K, et al. A case of pulmonary infective endarteritis associated with patent ductus arteriosus: surgical closure under circulatory arrest. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;59:563–5. 10.1007/s11748-010-0729-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Navaratnarajah M, Mensah K, Balakrishnan M, et al. Large patent ductus arteriosus in an adult complicated by pulmonary endarteritis and embolic lung abscess. Heart Int 2011;6:e16 10.4081/hi.2011.e16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kadakia R, Giullian J, Dokainish H. Patent ductus arteriosus complicated by pulmonary artery endarteritis in an adult. Echocardiography 2004;21:665–7. 10.1111/j.0742-2822.2004.04013.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sugimura Y, Katoh M, Toyama M. Patent ductus arteriosus with pulmonary endarteritis. Intern Med 2013;52:2157–8. 10.2169/internalmedicine.52.0897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bilge M, Uner A, Ozeren A, et al. Pulmonary endarteritis and subsequent embolization to the lung as a complication of a patent ductus arteriosus—a case report. Angiology 2004;55:99–102. 10.1177/000331970405500115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. George RH. The isolation of symbiotic streptococci. J Med Microbiol 1974;7:77–83. 10.1099/00222615-7-1-77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Christensen JJ, Facklam RR. Granulicatella and Abiotrophia species from human clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol 2001;39:3520–3. 10.1128/JCM.39.10.3520-3523.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kawamura Y, Hou XG, Sultana F, et al. Transfer of Streptococcus adjacens and Streptococcus defectivus to Abiotrophia gen. nov. as Abiotrophia adiacens comb. nov. and Abiotrophia defectiva comb. nov., respectively. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1995;45:798–803. 10.1099/00207713-45-4-798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schulthess B, Brodner K, Bloemberg GV, et al. Identification of Gram-positive Cocci by use of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry: comparison of different preparation methods and implementation of a practical algorithm for routine diagnostics. J Clin Microbiol 2013;51:1834–40. 10.1128/JCM.02654-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jayakeerthi SR, Kanungo R. Satelliting streptococci in an adult male with foetal heart. Indian J Med Microbiol 2002;20:223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Senn L, Entenza JM, Greub G, et al. Bloodstream and endovascular infections due to Abiotrophia defectiva and Granulicatella species . BMC Infect Dis 2006;6:9 10.1186/1471-2334-6-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al. Infective endocarditis. Circulation 2005;111:e394–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]