Abstract

Abciximab, the first approved glycoprotein (GP IIb/IIIa) inhibitor, is being widely used during acute coronary syndromes and offers the promising approach to antithrombotic therapy. We present a case of a young woman who initially received abciximab infusion for undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention of left anterior descending artery and was eventually diagnosed with abciximab-induced delayed thrombocytopaenia. This case outlines the importance of close follow-up of these patients to prevent serious adverse events.

Keywords: Cardiovascular system, Safety, Unwanted effects / adverse reactions

Background

Abciximab is widely being used during acute coronary syndromes and offers the promising approach to antithrombotic therapy. However, the use of abciximab has been associated with increased risk of thrombocytopaenia. Most cases are usually mild, but deaths have also been reported in some instances of severe thrombocytopaenia. The purpose of this case report is to increase awareness of abciximab-induced thrombocytopaenia among clinicians as early diagnosis could be invaluable in preventing the serious adverse outcomes.

Case presentation

A 20-year-old woman with medical history of obesity (body mass index of 41 kg/m2) and smoking (one pack per day) presented with atypical chest pain symptoms of 2 weeks duration. Her family history was negative for premature coronary artery disease and social history was otherwise unremarkable. On presentation, she had blood pressure of 163/100 mm Hg, respiratory rate of 22/min and heart rate of 102 beats/min. Physical examination was remarkable for S3 on cardiac examination. Initial blood work including complete blood count, basic metabolic panel and urine pregnancy test was negative. Suddenly, she developed a sustained monomorphic pulseless ventricular tachycardia (rate >200 beats/min) requiring emergent defibrillation. Following ECG showed anterior ST elevations with inferior reciprocal changes (figure 1). The initial set of troponins were elevated with the peak level of 5.03 ng/mL (reference range <0.030 ng/mL). She was immediately started on intravenous heparin, and emergent coronary angiography was performed that demonstrated 100% proximal occlusion of the left anterior descending artery (pLAD). Abciximab bolus was added to intravenous heparin before proceeding with coronary intervention. pLAD was successfully recanalised using 3.5×18 mm drug-eluting stent with re-establishment of TIMI grade 3 flow. Ventriculogram showed severely depressed 30% ejection fraction and severe anteroapical hypokinesis. There was no evidence of coronary dissection during coronary angiography. Repeat echocardiogram next day after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) showed 40%–45% ejection fraction with a moderate area of hypokinesis in anteroapical wall.

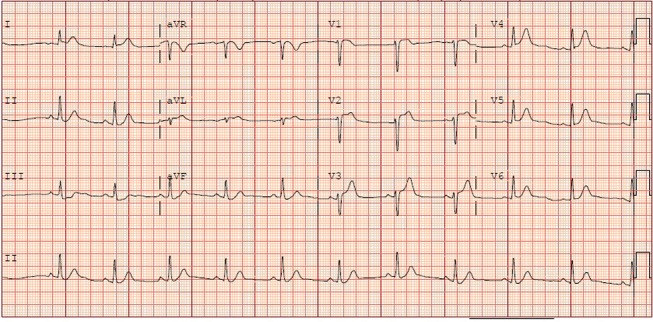

Figure 1.

ECG demonstrating anterior ST elevations with inferior reciprocal changes in our patient.

Investigations

A comprehensive hypercoagulability workup was considered given her young age (inclusive of antithrombin functional activity, factor V Leiden genetic testing, lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibodies, protein S and protein C levels) and was unremarkable. Inflammatory markers including erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C reactive protein were within normal reference range. Her haemoglobin A1c and lipid panel also showed no abnormalities. After an uncomplicated hospital course, she was discharged home on the third day on aspirin, prasugrel, atorvastatin and metoprolol succinate. Eight days after undergoing PCI, on her routine follow-up, it was noted on her complete blood count that platelets count dropped from 2 15 000 (day of discharge) to nadir 7000/μL (table 1).

Table 1.

Showing timeline of blood cell lines in our patient

| Timeline | Platelet count (per μL) | White cell count (per μL) | Haemoglobin (g/dL) |

| First admission | |||

| Day 1 (April 13 2015, underwent percutaneous coronary intervention with abciximab infusion) |

223 000 |

9000 |

13 |

| Day 4 (April 17 2015, discharged) |

215 000 |

6000 |

11.6 |

| Day 8 (April 21 2015, close outpatient follow-up) |

7000 |

6500 |

11.9 |

| Second admission | |||

| Day 1 (April 21 2015, readmitted, workup and treatment started) |

7000 | 6500 | 11.9 |

| Day 2 | 21 000 | 5200 | 11.4 |

| Day 3 | 52 000 | 7100 | 11.7 |

| Day 4 | 69 000 | 11 000 | 11.7 |

| Day 7 (April 28 2015, discharged) |

379 000 |

15 900 |

13.3 |

| Day 14 (May 4 2015, 1-week follow-up) |

335 000 |

12 900 |

12.5 |

| Day 36 (May 27 2015, 1-month follow-up) |

245 000 |

5000 |

12.5 |

| Day 63 (June 23 2015, 2-month follow-up) |

213 000 |

7500 |

12.8 |

Differential diagnosis

Workup for pseudothrombocytopaenia (citrate tube) and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) (fibrinogen, D-dimer, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time) was unremarkable. Peripheral blood smear was negative for schistocytes. Repeat renal function was normal and heparin immune thrombocytopaenia (HIT) panel for heparin–platelet factor 4 antibody was negative as well. After excluding potential causes of thrombocytopaenia, diagnosis of delayed abciximab-induced thrombocytopaenia was considered most likely.

Treatment

Emergent platelet transfusion was considered. She was started on oral prednisone and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) resulting in normalisation of her platelet counts within 7 days of therapy (table 1).

Outcome and follow-up

Reinstitution of aspirin and prasugrel was considered with no recurrence of thrombocytopaenia on follow-up.

Discussion

Platelet aggregation is one of the most crucial steps in coronary artery thrombus formation. A better understanding of the pathophysiology of thrombus formation has led to the development of newer agents to modulate the process of platelet aggregation. Of these, agents targeting the glycoprotein (GP IIb/IIIa) receptor are currently approved and recommended particularly in the setting of PCI. GP llb/llla belongs to the family of integrin receptor and serves as a receptor for von Willebrand factor1 and plays a key role in platelet aggregation. Abciximab, the first approved GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor, is being widely used during acute coronary syndromes and offers the promising approach to antithrombotic therapy.2 The chimeric Fab fragment of abciximab is directed against GP IIb/IIIa receptor3 and prevents the adhesion between fibrinogen, von Willebrand factor and other adhesive proteins,4 making it an effective and reliable antiplatelet agent of choice.

However, the use of abciximab has been associated with increased risk of thrombocytopaenia,5 similar to other GP llb/llla agents (tirofiban and eptifibatide). Most cases are usually mild, but deaths have also been reported in some instances of severe thrombocytopaenia.6 Acute profound life-threatening thrombocytopaenia has been reported in 1% of cases.4 The proposed mechanism is believed to be the formation of antibodies against its chimeric structural peptide sequence,7 the same sequence that provides abciximab its specificity for GP lla/lllb receptor. Moreover, another mechanism suggests that binding of GP llb/llla receptors to platelet surfaces results in increased number of ligand-induced binding sites on platelet surfaces causing platelet destruction.8 The reported incidence of thrombocytopaenia is 1% on first exposure and more than 10% on second exposure.7 The time of onset of thrombocytopaenia can be delayed up to 8–10 days in some patients after the initial dose of the drug,7 9 as seen in our patient. Acute thrombocytopaenia (0–4 days) is believed secondary to naturally occurring antibodies, while delayed thrombocytopaenia (5–10 days) is considered secondary to formation of antibodies to its chimeric peptide sequence.10 11

The diagnosis of abciximab-induced thrombocytopaenia should be considered usually after ruling out HIT, pseudothrombocytopaenia and DIC,12 as in our case. Currently, there is no standardised test11 and abciximab-specific antibodies are non-sensitive and non-specific.8 13 As the immune response is drug dependent, the thrombocytopaenia usually resolves with the clearance of drug after cessation and formation of new platelets by bone marrow.10 14 Treatment includes prompt cessation of the drug if platelet count drops below 50 000/μL. Platelet transfusion should be considered with if there is any stigmata of bleeding or platelet count drops below 20 000/μL.11 15 In cases of profound thrombocytopaenia, it may be reasonable to consider high dose IVIG and corticosteroids11 as in our case, although data of effectiveness of these supporting measures in acute settings are still lacking. So far, there are no reports of thrombocytopaenia associated with the use of prasugrel. Although aspirin may be rarely associated with thrombocytopaenia, our patient tolerated aspirin and prasugrel well with no recurrence of thrombocytopaenia on follow-up, confirming the diagnosis of delayed abciximab-induced thrombocytopaenia.

Learning points.

Delayed abciximab-induced thrombocytopaenia may be an underappreciated entity in mild and/or undiagnosed cases.

Clinicians should be aware of potential life-threatening thrombocytopaenia associated with it.

We propose close monitoring for platelet counts in these patients, at least for initial 1–2 weeks post discharge as early diagnosis could be invaluable in preventing the serious adverse outcomes.

Footnotes

Contributors: MJ and SB were responsible for the manuscript preparation, writing and data collection. KB and LC were responsible for the revision and critique review of the article.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Hynes RO. Integrins: a family of cell surface receptors. Cell 1987;48:549–54. 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90233-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.EPIC Investigators. Use of a monoclonal antibody directed against the platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor in high-risk coronary angioplasty. N Engl J Med 1994;330:956–61. 10.1056/NEJM199404073301402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coller BS. Platelet GPIIb/IIIa antagonists: the first anti-integrin receptor therapeutics. J Clin Invest 1997;99:1467–71. 10.1172/JCI119307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Usta C, Turgut NT, Bedel A. How abciximab might be clinically useful. Int J Cardiol 2016;222:1074–8. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.07.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aster RH. Immune thrombocytopenia caused by glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. Chest 2005;127(2 Suppl):53S–9. 10.1378/chest.127.2_suppl.53S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCorry RB, Johnston P. Fatal delayed thrombocytopenia following abciximab therapy. J Invasive Cardiol 2006;18:E173–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aster RH, Bougie DW. Drug-induced immune thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med 2007;357:580–7. 10.1056/NEJMra066469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peters MN, Press CD, Moscona JC, et al. Acute profound thrombocytopenia secondary to local abciximab infusion. Proc 2012;25:346–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtis BR, Divgi A, Garritty M, et al. Delayed thrombocytopenia after treatment with abciximab: a distinct clinical entity associated with the immune response to the drug. J Thromb Haemost 2004;2:985–92. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00744.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giupponi L, Cantoni S, Morici N, et al. Delayed, severe thrombocytemia after abciximab infusion for primary angioplasty in acute coronary syndromes: moving between systemic bleeding and stent thrombosis. Platelets 2015;26:498–500. 10.3109/09537104.2014.898181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arnold DM, Nazi I, Warkentin TE, et al. Approach to the diagnosis and management of drug-induced immune thrombocytopenia. Transfus Med Rev 2013;27:137–45. 10.1016/j.tmrv.2013.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Llevadot J, Coulter SA, Giugliano RP. A practical approach to the diagnosis and management of thrombocytopenia associated with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2000;9:175–80. 10.1023/A:1018779116791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nowakowski K, Rogers J, Nelson G, et al. Abciximab-induced thrombocytopenia: management of bleeding in the setting of recent coronary stents. J Interv Cardiol 2008;21:100–5. 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2007.00296.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Caterina R, Zimarino M. Understanding the complexity of abciximab-related thrombocytopenia. Thromb Haemost 2010;103:484–6. 10.1160/TH10-01-0016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giugliano RP. Drug-induced thrombocytopenia: is it a serious concern for glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors? J Thromb Thrombolysis 1998;5:191–202. 10.1023/A:1008887708104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]