Abstract

Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) catheter site metastasis in cases of cholangiocarcinoma is reported sporadically. But it is unusual to see left-sided tumour metastasising to the right PTBD catheter site. Metastasis, in general, has a poor prognosis, but recurrence along the catheter tract in the absence of other systemic diseases can be a different scenario altogether. To date, there is no consensus on the management of this form of metastasis. But carefully selected patients can benefit from aggressive surgical resection. We report a case of a young patient with isolated chest wall metastasis 1 year after resection of left-sided hilar cholangiocarcinoma. The metastasis was resected and, on pathological analysis, was confirmed to be due to implantation of malignant cells along the tract of the PTBD catheter placed via a transpleural route.

Keywords: Biliary intervention, Surgery, Gastrointestinal surgery

Background

Since 1973, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) has been widely practised for malignant biliary obstruction with diagnostic, therapeutic and palliative intent.1 2 While minor complications such as pain (20%), catheter slippage (18%) and catheter block (27%) are common, more serious complications such as bleeding, flaring of cholangitis, biliary peritonitis and sepsis can occur in 7%–10% of cases.3 4 Moreover, there has been a growing concern for catheter tract metastases which occurs in 0.6%–6% of cases.5 Although many surgeons condemn the percutaneous route in favour of endoscopic drainage,6 the modality is still of immense value in high and complex biliary obstruction where the endoscopic route can fail.

Case presentation

A 41-year-old man presented to our clinic with a painful swelling on his right lower chest wall. On examination, a 5×5 cm hard tender nodule was palpable in the right anterolateral chest wall over the sixth rib and adjacent intercostal spaces (figure 1). The lump was fixed to the chest wall. The overlying skin was freely movable but showed a scar which corroborated with a previous PTBD insertion.

Figure 1.

Clinical (A), preoperative (B) and intraoperative (C) images of the chest wall metastasis (black arrow) and its relation with ribs marked with a marker during surgery.

On reviewing his medical records, it was found that he is a follow-up case for type-IIIB hilar cholangiocarcinoma. One year earlier, he had developed painless progressive cholestatic jaundice associated with loss of weight and appetite. His maximum preoperative serum bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase were 16 mg/dL and 425 IU/L, respectively. Cross-sectional imaging revealed bilobar intrahepatic biliary radical dilatation (IHBRD) with a heterogeneous soft tissue mass at the primary confluence (figure 2). The patient developed cholangitis during preoperative evaluation. Repeated endoscopic drainage attempts failed to negotiate the tight hilar stricture. Interventional radiology opinion was sought in desperation as cholangitis worsened. An 8 French PTBD catheter was placed via a transpleural approach into the right ductal system and advanced into the common bile duct. The left duct was drained simultaneously via an epigastric route. On recovery from cholangitis, he underwent left hepatectomy with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. Drainage catheters were removed during surgery. The histopathology report showed left ductal cholangiocarcinoma with clear surgical margins. The harvested lymph nodes harboured no metastasis. Following postoperative recovery, he received 45 Gy external beam radiation and three cycles of gemcitabine-based and oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy.

Figure 2.

Axial cut contrast-enhanced CT image of the primary tumour seen as hypodense soft tissue at the primary confluence (white arrow) with bilobar intrahepatic biliary radical dilatation.

Investigations

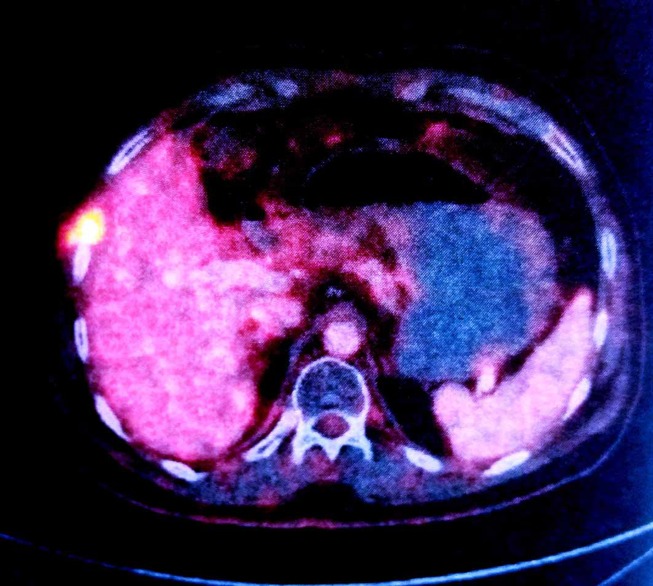

A follow-up positron emission CT (PECT) after completion of adjuvant therapy revealed an intensely fluoro deoxy glucose (FDG)-avid (maximum standardised uptake value (SUVmax) 10.80) lesion in the subcapsular region of segment VII of the liver extending through the sixth intercostal space into the subcutaneous plane associated with a cystic lesion (figure 3). Clinically, patient was asymptomatic and no lump was palpable. Image-guided Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) was also inconclusive and patient was closely followed up until the lesion became clinically apparent in 2-month time.

Figure 3.

Follow-up positron emission CT scan showing intensely FDG-avid right chest wall lesion in relation to the sixth rib abutting segment VII of the right lobe of the liver.

A contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen and chest was done at the present follow-up which revealed a heterogeneous soft tissue lesion (3.4×3.3×1.8 cm) in the right anterolateral chest wall extending through the sixth intercostal space and causing indentation on segment VII of the liver (figure 4). A true-cut biopsy confirmed it to be metastatic adenocarcinoma. As there was no clinical or radiological evidence of intra-abdominal and systemic dissemination and the recurrence was exactly at the old PTBD catheter site, a diagnosis of isolated implant metastasis of the catheter tract was made in a multidisciplinary meeting involving surgeons, radiologists and a radiotherapist. A decision of surgical resection via a direct transpleural core down approach was made.

Figure 4.

Axial contrast-enhanced CT image showing a heterogeneous cystic lesion in the right anterolateral chest wall.

Treatment

During surgery the metastasis was resected en-bloc from the skin down to the liver surface with segments of the sixth and seventh rib, intercostal muscle, parietal pleura and disc of the diaphragm keeping a 2 cm circumferential margin (figures 5 and 6). The diaphragmatic defect was closed using a PTFE patch. No attempt was made to reconstruct the rib cage defect. Soft tissue and skin flaps were mobilised and apposed primarily after placing a chest tube. The patient made an uneventful recovery and was discharged in a satisfactory condition.

Figure 5.

Intraoperative image showing en-bloc metastatectomy incorporating skin, soft tissue, rib segments, disc of diaphragm and part of the liver.

Figure 6.

En-bloc metastatectomy specimen comprising skin, subcutaneous tissue, rib segments, intercostal muscles, diaphragm and liver tissue.

Outcome and follow-up

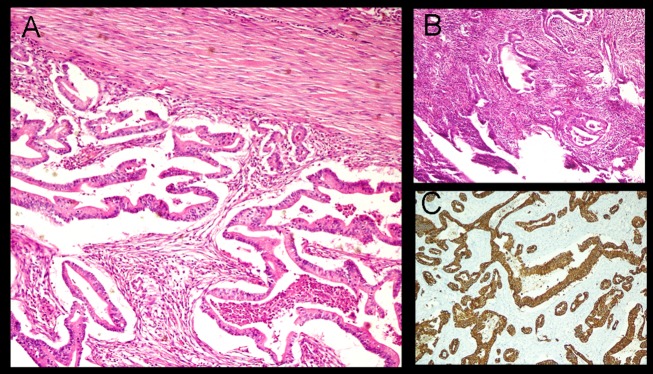

Pathological analysis of the resected specimen revealed a cystic nodule (2×2×1.5 cm) in the subcutaneous plane filled with greenish jelly. It had a wall thickness of 0.1 cm. Microscopic examination revealed a cyst wall lined by multilayered pleomorphic tumour cells with vesicular to hyperchromatic nuclei and moderate amount of cytoplasm (figure 7). The surrounding stroma showed desmoplastic reaction with myxoid degeneration and foamy macrophages. The epidermis and dermis were free but the underlying soft tissue, skeletal muscle and diaphragm were invaded by tumour cells. The resected wedge of the liver only showed features of chronic macrovesicular steatohepatitis. Tumour cells showed membranous positivity for CK 7 (figure 7) confirming our previous postulation of catheter tract implant metastasis.

Figure 7.

Photomicrograph of the specimen showing (A) irregular glands lined by moderately pleomorphic tumour cells with vesicular chromatin and prominent nucleoli in the deep dermis and (B) a typical neutrophil rich fibroinflammatory stroma (H&E 200×). (C) Immunostaining of tumour cells showing strong diffuse membranous positivity for CK 7 (200×).

Presently, the patient is asymptomatic and under close follow-up. After six postoperative weeks, a follow-up PECT (figure 8) was done which showed inflammatory changes at the surgical site (SUVmax 5.1). Serum carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19.9 level was 5.0 IU/mL. He was started on oral capecitabine therapy on completion of which PECT and CA 19.9 level will be repeated.

Figure 8.

Positron emission CT image after six postoperative weeks showing no residual disease except inflammatory changes at the surgical site.

Discussion

Metastasis of biliary and pancreatic tumours along the PTBD catheter tract is a unique phenomenon and less commonly reported than port site metastasis following laparoscopic removal of incidental gall bladder cancers. While the approximate incidence of port site metastasis is around 10%,7 catheter tract recurrence is seen in only 0.6%–6% of cases.5 The precise mechanism of catheter tract metastasis is unclear but appears analogous to the mechanism for port site metastasis. While venturi effect of pneumoperitoneum along with its immunity lowering capability promotes the seeding of malignant cells at port site, inflammation initiated by surgical trauma favours their proliferation. Given the observation that catheter tract recurrence is more likely with long duration catheters, multiple catheters, repeated manipulations or exchanges and that more than one-third of malignant biliary obstructions are associated with positive bile cytology,8 it is postulated that malignant cells in the bile stick to the catheter, puncture the needle or guide wire during manipulation and disseminate along the tract.

In 1982, Oleaga et al 9 reported the first case of cutaneous metastasis in hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Since then, similar cases have been reported anecdotally in the medical literature.2 4 5 8 10–16 In a retrospective review of PTBD tract metastasis by Sakata et al,5 the incidence of catheter tract metastasis was found to be 4.5%. A pooled analysis of all reported cases until 2005 (n=10) found that the median time to detection was 14 months postinsertion, 60% were isolated and 40% had well differentiated tumour histology.5 A similar review by Rosich-Medina et al 16 subsequently showed that the mean age of patients was 68 years and mean time to detection was 9 months with a male predominance. Based on their 30 years of experience (1977–2007) of treating 445 patients with cholangiocarcinoma with preoperative PTBD, Takahashi et al 6 reported 25 catheter tract recurrences in 23 patients (two patients with two metastases each; incidence 5.2%). These were predominantly metachronous in nature (82.6%), occurring within first 1.5 years of surgery. Prolonged catheterisation, multiple catheters or manipulations, papillary histology and well-differentiated tumours were found to significantly predispose to catheter tract seeding. In 2015, Liu et al 17 reviewed the English literature and found 30 reported cases of cutaneous metastasis in hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Half of these cases occurred at the PTBD catheter site and two-thirds were solitary. Three-fourth of them occurred in men.

In the absence of consensus, some observers considered catheter tract recurrence to be incurable and have taken a palliative approach while others have contemplated aggressive surgical resection.6 Takahashi et al 6 advocate en-bloc resection of isolated metastasis along with excision of the catheter tract, which may require liver resection. In their opinion, all PTBD catheter tracts should be extirpated during curative surgery of primary tumours. Shimizu et al,14 Uesaka et al 18 and Kondo et al 19 tried ethanol injection into the tract with mixed results. Overall survival after detection has been reported to be as poor as 4 months, with male sex, solitary lesions and recurrence within the first year having worst outcomes.6 17 However, the patient’s age and the number and size of the metastasis did not seem to affect the prognosis. Sakata et al 5 observed that 80% of patients with isolated PTBD tract metastasis survived more than a year following resection. The median survival of six patients undergoing resection was 22.5 months (range 9–65 months) with two surviving beyond 5 years and three surviving more than 2 years.5 In a review by Rosich-Medina et al,16 postexcision median survival was 10.5 months (n=4; range 8–18 months).

Learning points.

The small but sizeable risk of catheter tract seeding should be borne in mind while using percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) for biliary decompression in malignant biliary obstruction.

Complete extirpation or chemical ablation of such catheter tracts during curative surgery should be strongly considered to reduce the risk of subsequent recurrence.

Carefully selected patients of catheter tract recurrence with no other forms of systemic metastasis can benefit from aggressive surgical treatment.

Footnotes

Contributors: ST, CT and SM were involved in data acquisition, analysis and concept designing of the manuscript. ST and CT together drafted and revised it, while AB and SM provided intellectual input in writing the manuscript. ST and AB approved the version of the manuscript to be published. ST is accountable for the authenticity and accuracy of the article.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Molnar W, Stockum AE. Relief of obstructive jaundice through percutaneous transhepatic catheter--a new therapeutic method. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1974;122:356–67. 10.2214/ajr.122.2.356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Geramizadeh B, Giti R, Malekhosseini SA. Cutaneous metastasis of cholangiocarcinoma: report of two cases. Int J Organ Transplant Med 2013;4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mueller PR, van Sonnenberg E, Ferrucci JT. Percutaneous biliary drainage: technical and catheter-related problems in 200 procedures. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1982;138:17–23. 10.2214/ajr.138.1.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Balzani A, Clerico R, Schwartz RA, et al. Cutaneous implantation metastasis of cholangiocarcinoma after percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2005;13:0–-0.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sakata J, Shirai Y, Wakai T, et al. Catheter tract implantation metastases associated with percutaneous biliary drainage for extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:7024–7. 10.3748/wjg.v11.i44.7024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Takahashi Y, Nagino M, Nishio H, et al. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage catheter tract recurrence in cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg 2010;97:1860–6. 10.1002/bjs.7228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Berger-Richardson D, Chesney TR, Englesakis M, et al. Trends in port-site metastasis after laparoscopic resection of incidental gallbladder cancer: a systematic review. Surgery 2017;161 10.1016/j.surg.2016.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mizuno T, Ishizaki Y, Komuro Y, et al. Surgical treatment of abdominal wall tumor seeding after percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. Am J Surg 2007;193:511–3. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oleaga JA, Ring EJ, Freiman DB, et al. Extension of neoplasm along the tract of a transhepatic tube. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1980;135:841–2. 10.2214/ajr.135.4.841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Demas BE, Moss AA, Goldberg HI. Computed tomographic diagnosis of complications of transhepatic cholangiography and percutaneous biliary drainage. Gastrointest Radiol 1984;9:219–22. 10.1007/BF01887838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shorvon PJ, Leung JW, Corcoran M, et al. Cutaneous seeding of malignant tumours after insertion of percutaneous prosthesis for obstructive jaundice. Br J Surg 1984;71:694–5. 10.1002/bjs.1800710916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tersigni R, Rossi P, Bochicchio O, et al. Tumor extension along percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage tracts. Eur J Radiol 1986;6:280–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Loew R, Dueber C, Schwarting A, et al. Subcutaneous implantation metastasis of a cholangiocarcinoma of the bile duct after percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD). Eur Radiol 1997;7:259–61. 10.1007/s003300050147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shimizu Y, Yasui K, Kato T, et al. Implantation metastasis along the percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage sinus tract. Hepatogastroenteroly 2003;51:365–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Singh MK, Rodriguez-Davalos M, Wolf DC, et al. Metastatic cholangiocarcinoma at percutaneous drain site. Cureus 2013;5 10.7759/cureus.87 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rosich-Medina A, Liau SS, Jah A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from cholangiocarcinoma following percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage: case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep 2010;1:33–6. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2010.08.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu M, Liu BL, Liu B, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of cholangiocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:3066 10.3748/wjg.v21.i10.3066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Uesaka K, Kamiya J, Nagino M, et al. [Treatment of recurrent cancer after surgery for biliary malignancies]. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi 1999;100:195–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kondo S, Nimura Y, Hayakawa N, et al. Ethanol injection for prevention of seeding metastasis along the tract after percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. J Jpn Bil Assoc 1989;3:100–5. [Google Scholar]