Abstract

Rectus sheath haematoma is a rare cause of abdominal pain. It can be easily confused for other causes of acute abdomen and may even lead to unnecessary laparotomies. Our patient has the rectus sheath haematoma because of violent coughing and on presentation had no obvious clinical sign pointing to the same. Diagnosis was made by a CT scan of the abdomen, and patient was treated conservatively. Rectus sheath haematomas are usually present on the posterior aspect of the rectus muscles and thus may not be clinically appreciable.

Keywords: Musculoskeletal syndromes, General practice / family medicine

Introduction

Rectus sheath haematoma (RSH) is a rare cause of abdominal pain. It can mimic other more life-threatening causes of acute abdomen. If not looked for it may cause clinicians to perform unnecessary laparotomies. Patients who are on anticoagulation are at high risk for getting RSH. Being mostly posterior in location in relation to the rectus muscle, it may not appreciable clinically on examination. A good history is necessary for diagnosis.

Case presentation

The patient was a 56-year-old male with significant medical history of coronary artery disease and presented to us with pain abdomen, which was periumbilical and severe. The patient had recent history of acute bronchitis and had been coughing a lot. The bronchitis was settling at the time of admission. He was not on any anticoagulants but was on aspirin. On examination, his abdomen was very tender. There was no mass palpable in the abdomen. There were no other significant clinical findings at the time. His vitals were stable. However, next day he was noted to have periumbilical ecchymosis (Cullen sign and Grey Turner sign, figure 1).

Figure 1.

Picture showing bruising around the umbilicus and flank because of the rectus sheath haematoma. The bruising around the umbilicus is called the Cullen sign and the bruising of the flank is called Grey Turner sign. Other causes of Cullen sign are acute pancreatitis, abdominal trauma and ectopic pregnancy. Other cause of Grey Turner sign is pancreatic necrosis.

Investigations

The complete blood count showed a haemoglobin of 12.1 g/dL against a baseline of around 14 g/dL. A CT scan of the abdomen was done which showed asymmetric lenticular thickening of the left rectus abdominus measuring up to 3.7 cm in thickness just above the level of the umbilicus. This spanned approximately 15 cm transversely and 22 cm cranial caudally (figures 2 and 3). This was suggestive of a confined RSH. Coagulogram and serum lipase were normal. There were no other lab abnormalities.

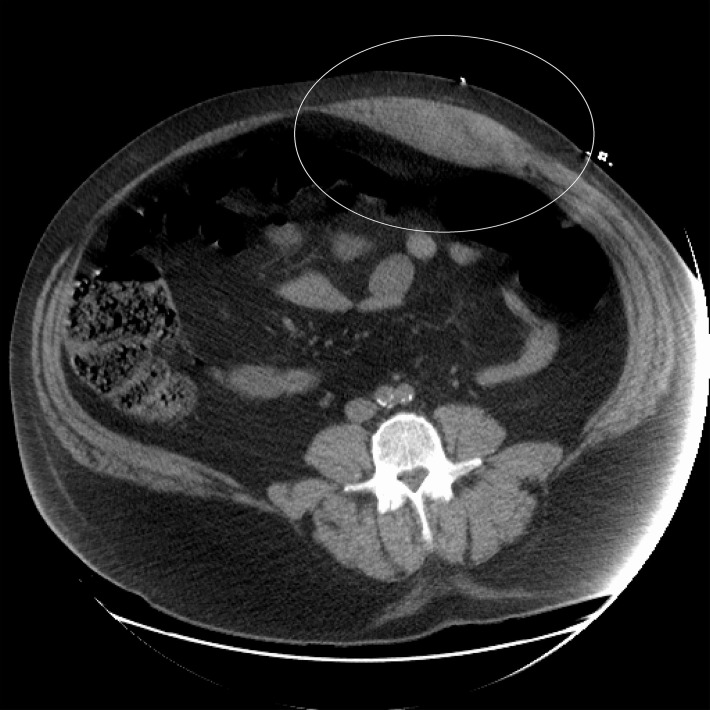

Figure 2.

CT scan showing the rectus sheath haematoma as pointed by the circle. Note the posterior location of the haematoma in relation to the rectus muscle.

Figure 3.

CT scan showing the rectus sheath haematoma. Note the long extent of the haematoma.

Differential diagnosis

This patient’s clinical history was suggestive of an acute abdomen, and the differentials were broad and RSH was not one of the top ones. The chief differentials on clinical history and exam were gut ischaemia, bowel obstruction, acute pancreatitis, appendicitis and a ruptured viscus. However, on radiological testing, these were ruled out and RSH was the final diagnosis.

Treatment

Patient was managed conservatively with rest, analgesics, haematoma compression, ice packs and monitoring of clinical status. A close watch was kept on the size of the haematoma and the haemoglobin of the patient. The RSH remained stable, and there was no observable drop in the haemoglobin of the patient.

Outcome and follow-up

Patient did well with conservative management, the haematoma size slowly decreased, the pain subsided and his haemoglobin came back up to 14 g/dL in 3–4 weeks at follow-up. The superficial ecchymosis resolved and the patient has been doing well since.

Discussion

RSH is an unusual cause of abdominal pain and an abdominal mass. Awareness of the condition and early diagnosis made with focused history, physical examination and imaging of the abdomen and pelvis may help decrease unnecessary workup for other conditions and lead to better triage of patients who present with RSH.1 Haematomas are more often seen in the lower segment of the rectus sheath posteriorly.2 This is because lower section of the muscle is the longest and consequently shortening during contraction is greatest.3 The posterior location of the haematoma may make it difficult to be appreciated on physical exam. Our patient had the haematoma in the posterior location making it difficult to be palpated. RSHs are usually caused either by rupture of one of the epigastric arteries or by a muscular tear. The immediate cause of the rupture may be trauma to the abdominal wall, surgery or excessively vigorous contractions of the rectus muscle. These vigorous contractions are often produced during strenuous exercise, severe coughing, vomiting or straining during defecation. In our patient, the cause of the RSH was vigorous coughing. The association with abdominal trauma has been noted in Ancient Greek literature. Anticoagulation has a strong association with RSH.4 Due to growing use of anticoagulants, more patients are expected to present with this condition thus making it important for the modern physician to be aware of the condition.5 Ultrasound may be the first imaging modality used for the diagnosis of RSH but sometimes CT scan is necessary to see the origin and extent of the haematoma.5

Learning points.

Rectus sheath haematoma can mimic other causes of acute abdomen and may sometimes prompt for a laparotomy unless it is specifically looked for.

Rectus sheath haematoma may not be palpable if it is present posteriorly and thus may be missed.

The history of violent coughing or severe abdominal strain may point to this diagnosis.

Footnotes

Contributors: KHC: planning, conduct, reporting, conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data. Writing the manuscript.

SS: acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data. Editing the manuscript.

GG: acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data. Editing the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Cherry WB, Mueller PS. Rectus sheath hematoma: review of 126 cases at a single institution. Medicine 2006;85:105–10. 10.1097/01.md.0000216818.13067.5a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fukuda T, Sakamoto I, Kohzaki S, et al. Spontaneous rectus sheath hematomas: clinical and radiological features. Abdom Imaging 1996;21:58–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Klingler PJ, Wetscher G, Glaser K, et al. The use of ultrasound to differentiate rectus sheath hematoma from other acute abdominal disorders. Surg Endosc 1999;13:1129–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cherry WB, Mueller PS. Rectus sheath hematoma: review of 126 cases at a single institution. Med Baltim 2006;85:105–10. 10.1097/01.md.0000216818.13067.5a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hatjipetrou A, Anyfantakis D, Kastanakis M, et al. Rectus sheath hematoma: a review of the literature. Int J Surg 2015;13 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]