Abstract

Antibiotic-associated colitis is a gastrointestinal complication of antibiotic use commonly seen in hospitalised patients, with Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) colitis being the most common type. We present a case of haemorrhagic colitis secondary to Klebsiella oxytoca following self-initiated amoxicillin–clavulanic acid use. An 85-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain and mucobloody diarrhoea. History was notable for an ongoing 5-day course of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid use. The CT scan of her abdomen revealed extensive diffuse thickening of the ascending and transverse colon. Stool culture grew K. oxytoca, an established cause of haemorrhagic colitis. She declined colonoscopy but recovered with withdrawal of all antibiotics and conservative treatment. We should be vigilant to haemorrhagic colitis following antibiotic use which is not always C. difficile related.

Keywords: infection (gastroenterology), gastroenterology

Background

Antibiotic-associated haemorrhagic colitis (AAHC) is a subtype of antibiotic-associated colitis, which is especially associated with the use of penicillin antibiotics.1 2 Causality by Klebsiella oxytoca has been demonstrated in animal models and biopsy specimens of patients with colitis.3 4 We report a patient with haemorrhagic colitis caused by K. oxytoca after a course of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid for an upper respiratory tract infection. Although symptoms are similar to Clostridium difficile colitis, we should be watchful for AAHC caused by K. oxytoca, as management is conservative and further antibiotic use could be detrimental.

Case presentation

An 85-year-old Chinese woman with a past medical history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia and hypothyroidism, presented to the emergency department of our hospital with a 1-day history of severe, cramping, intermittent low abdominal pain and seven to eight episodes of mucobloody diarrhoea. These were associated with nausea, but no vomiting or fever. There was no history of recent travel, sick contacts, smoking, alcohol use or allergies. Her daily medications included amlodipine, glipizide, simvastatin and levothyroxine. A week prior to presentation, she had a fever and sore throat and had been taking amoxicillin–clavulanic acid for 5 days prior to presentation for a presumed upper respiratory tract infection.

Investigations

On physical examination, she was calm, cooperative and in no acute distress. She weighed 59 kg and was 160 cm tall. Her blood pressure was 116/58 mm Hg, heart rate 70 per minute, temperature 97.8°F, respiratory rate 18 per minute and arterial oxygen saturation was 96% on ambient air. Head and neck examination was normal, oral mucosa was moist, with no oral thrush or ulcers noted. There were no abnormal lung or heart sounds. Abdomen was soft, non-distended, non-tender, with no rebound or guarding and normal bowel sounds. Digital rectal examination was remarkable for mucobloody stool.

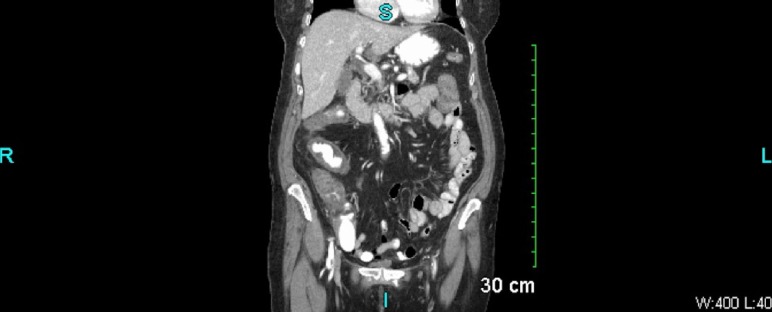

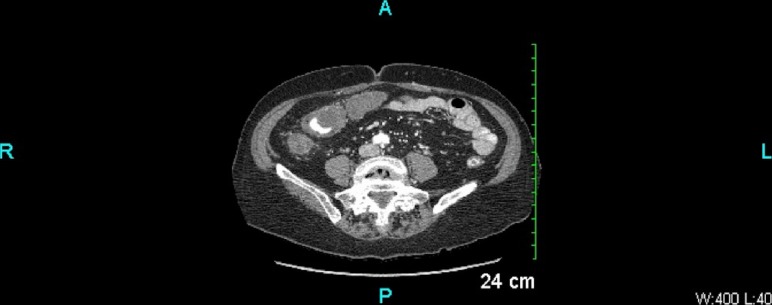

Her laboratory tests showed leucocytosis of 13 900/µL with 87% neutrophils, haemoglobin 13.4 mg/dL, potassium 3.7 mmol/L, bicarbonate 22 mmol/L and an anion gap of 8. Recent outpatient labs showed thyroid-stimulating hormone level of 1.863 mIU/L and haemoglobin-A1C of 6.0%. Other laboratory data were normal. A contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen (figures 1 and 2) showed extensive diffuse thickening of the ascending and transverse colon extending from the caecum to splenic flexure with mild surrounding fat stranding. There was no obstruction, perforation or abscesses seen. Stool studies including stool leucocytes, ova and parasites, and C. difficile toxin PCR were negative. Stool culture was positive for K. oxytoca which has been reported to cause AAHC.3 4

Figure 1.

Coronal CT image of the abdomen and pelvis showing extensive diffuse thickening of the ascending and transverse colon extending from the caecum to splenic flexure with mild surrounding fatty stranding. No obstruction, perforation or abscess is seen.

Figure 2.

Transverse CT image of the abdomen and pelvis showing extensive diffuse thickening of the ascending and transverse colon extending from the caecum to splenic flexure with mild surrounding fatty stranding. No obstruction, perforation or abscess is seen.

Differential diagnosis

Possible diagnoses in this patient included antibiotic-associated colitis (secretory, functional, osmotic or haemorrhagic), ischaemic colitis, infectious colitis and inflammatory bowel disease. Prior to the availability of the results of stool studies, antibiotic-associated colitis due to C. difficile was strongly suspected due to the recent antibiotic use. However, with the stool culture results, AAHC secondary to K. oxytoca was the most likely diagnosis. No further bacteria including Salmonella, Shigella, Aeromonas, Plesiomonas, Edwardsiella, Campylobacter or Escherichia coli species were isolated. She had no previous personal or family history of inflammatory bowel disease.

Treatment

She was admitted to the medical floor and was initially started on clear liquid diet, intravenous fluids and intravenous metronidazole as empiric treatment for infectious colitis likely secondary to C. difficile colitis. However, her symptoms did not improve and her white cell count trended up to 19 500/µL. Stool culture results obtained on the third day of hospitalisation led to the eventual diagnosis of AAHC secondary to K. oxytoca. Intravenous metronidazole was immediately discontinued which led to a remarkable improvement in the patient’s symptoms and laboratory values over the next day or two.

Outcome and follow-up

Her symptoms of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea completely resolved following cessation of antibiotic therapy and with supportive care. She declined to undergo a colonoscopy. Her diet was advanced to a low-fibre diet and she was discharged home in a stable condition on hospital day 5. She was scheduled for an outpatient gastroenterology follow-up and was counselled to avoid unnecessary antibiotic use in future.

Discussion

Antibiotic-associated colitis is an undesirable complication of antibiotic use causing diarrhoea. Impaired carbohydrate metabolism, hastened gut motility and decreased metabolism and excretion of bile acids, are some of the mechanisms by which antibiotics may cause osmotic, functional or secretory diarrhoea, respectively.5 Haemorrhagic colitis related to antibiotic use has also been described.3 4

AAHC is a distinct form of antibiotic-associated colitis most commonly associated with use of penicillin derivatives.1 Most case reports of AAHC due to K. oxytoca in the medical literature are from Asia and Europe and there have been very few similar cases reported in the USA. The first North American case was described in 2004.6 Quinolones, macrolides and cephalosporins have also been associated with such cases of AAHC.7–9 A causal association has been demonstrated between AAHC and toxigenic strains of K. oxytoca via experimental animal models and also colonic biopsy specimens from patients with acute colitis.3 4 Conversely, it has also been shown that Klebsiella oxytoca plays no role in the development of non-haemorrhagic antibiotic-associated colitis.10

Due to the inherent resistance of Klebsiella to penicillin, its use leads to an overgrowth of K.oxytoca in the colon of colonised individuals.3 Toxigenic strains of Klebsiella in high concentrations then induce mucosal damage and cell death via cytotoxin production leading to a predominantly right-sided colitis.2 3 Our patient most likely developed haemorrhagic colitis due to amoxicillin–clavulanic acid use.

Management of AAHC due to K. oxytoca is mainly conservative.3 Patients should be supported with fluids, antiemetics and diet as tolerated. Colonoscopy and biopsy are important to demonstrate macroscopical and histological features of haemorrhagic colitis. All antibiotics should be immediately withdrawn. Concurrent non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should also be stopped as they have been associated with colitis and diarrhoea and may potentially worsen AAHC.3

Hence, our case report illustrates the need to consider K. oxytoca colitis as a differential diagnosis in patients presenting with antibiotic-associated colitis. This is even more important in patients diagnosed with AAHC and negative C. difficile testing. Isolation of K. oxytoca in stool cultures should prompt immediate withdrawal of all antibiotics and continuation of supportive therapy. While not a common diagnosis, it does carry significant morbidity and a potential for mismanagement and adverse patient outcomes. Our case aims to increase vigilance to K. oxytoca-associated haemorrhagic colitis to avoid unnecessary and potentially harmful treatments.

Learning points.

Clostridium difficile colitis is not the only cause of antibiotic-associated colitis.

Antibiotic use can lead to antibiotic-associated haemorrhagic colitis due to Klebsiella oxytoca.

Prompt recognition of antibiotic-associated haemorrhagic colitis is crucial as delay in diagnosis can lead to unnecessary and potentially harmful interventions causing more morbidity and delay in recovery.

Footnotes

Contributors: OA: drafting of manuscript. NS: concept and drafting of manuscript. MS and BSP: literature review.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Moulis H, Vender RJ. Antibiotic-associated hemorrhagic colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 1994;18:227–31. 10.1097/00004836-199404000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toffler RB, Pingoud EG, Burrell MI. Acute colitis related to penicillin and penicillin derivatives. Lancet 1978;2:707–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(78)92704-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Högenauer C, Langner C, Beubler E, et al. Klebsiella oxytoca as a causative organism of antibiotic-associated hemorrhagic colitis. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2418–26. 10.1056/NEJMoa054765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beaugerie L, Metz M, Barbut F, et al. Klebsiella oxytoca as an agent of antibiotic-associated hemorrhagic colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003;1:370–6. 10.1053/S1542-3565(03)00183-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Högenauer C, Hammer HF, Krejs GJ, et al. Mechanisms and management of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis 1998;27:702–10. 10.1086/514958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J, Cachay ER, Hunt GC. Klebsiella oxytoca: a rare cause of severe infectious colitis: first north american case report. Gastrointest Endosc 2004;60:142–5. 10.1016/S0016-5107(04)01537-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koga H, Aoyagi K, Yoshimura R, et al. Can quinolones cause hemorrhagic colitis of late onset? Report of three cases. Dis Colon Rectum 1999;42:1502–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyauchi R, Kinoshita K, Tokuda Y. Clarithromycin-induced haemorrhagic colitis. BMJ Case Rep 2013;2013:bcr2013009984 10.1136/bcr-2013-009984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellaïche G, Le Pennec MP, Choudat L, et al. [Value of rectosigmoidoscopy with bacteriological culture of colonic biopsies in the diagnosis of post-antibiotic hemorrhagic colitis related to Klebsiella oxytoca]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 1997;21:764–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zollner-Schwetz I, Högenauer C, Joainig M, et al. Role of Klebsiella oxytoca in antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:e74–e78. 10.1086/592074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]