Abstract

Cryptococcosis is a recognised opportunistic infection in immunocompromised patients. The long-term adverse effect profile of fingolimod, an immunomodulating agent approved for use in multiple sclerosis in 2010, is only just emerging. We report the first case to our knowledge of a patient presenting with obstructive hydrocephalus secondary to cryptococcal meningitis in the setting of fingolimod therapy. Extensive posterior fossa leptomeningeal inflammation with associated cerebellar oedema resulted in effacement of the fourth ventricle and obstructive hydrocephalus requiring urgent ventriculostomy. Induction, consolidative and maintenance antifungal therapy was prescribed and subsequent conversion to a ventriculoperitoneal shunt was successful in relieving the patient’s ventriculomegaly. Awareness of these rare, novel and life-threatening complications of fingolimod-associated immunocompromise is critical as the use of such drugs is expected to rise.

Keywords: immunological products and vaccines, meningitis, multiple sclerosis, infection (neurology), neurosurgery

Background

Multiple sclerosis is an auto-inflammatory condition involving T lymphocytes in the demyelination of central nervous system (CNS) axons. Development of disease-modifying therapies have led to challenges in identifying their potential long-term unintended side effects.

Fingolimod is the first oral agent approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (2010) and European Medicines Agency (2011) for maintenance therapy of relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. Its mechanism of action is through downregulation of T cell sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors with subsequent lymphopaenia from T cell sequestration. The safety profile of fingolimod is reported to be comparable with other agents from landmark trials with no increased risk of serious infection when compared with placebo.1 However, instances of opportunistic infections are beginning to emerge.

The aim of this publication is to highlight the possibility of significant opportunistic infections in patients with multiple sclerosis on immunomodulating agents and present the rare complication of obstructive hydrocephalus that has not been previously described in this setting. Differentiating between the neurological symptoms of CNS cryptococcosis and hydrocephalus can be challenging but is essential to avoid preventable morbidity and mortality.

Case presentation

A 61-year-old woman presented with a 2-week history of headache and neck pain exacerbated by exertion (eg, coughing). There was associated nausea, vertigo and an unintentional loss of 10 kg in weight. She had an extensive travel history to the UK, Netherlands, Poland, United Arab Emirates, South Africa and Thailand in the last 12 months.

Her medical history was significant for relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis diagnosed 10 years prior. She was commenced on fingolimod (Gilenya) 3 years ago when she tested positive to John Cunningham virus antibodies and her previously prescribed natalizumab (Tysabri) infusions were discontinued. She subsequently developed a fingolimod-induced lymphopaenia, which was monitored.

The patient was initially alert on presentation with a Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) of 15. Apart from right-beating nystagmus on right lateral gaze, neurological examination was unremarkable with no papilloedema. On the second night following her admission, she reported worsening headache and was noted to be increasingly drowsy with confused speech and a GCS of 14.

Investigations

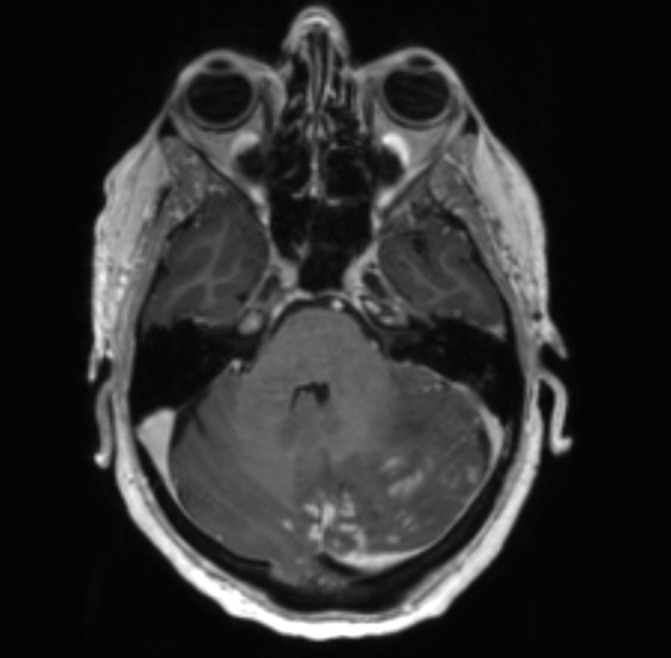

Full blood examination showed profound lymphopaenia (120/μL) with a CD4 count of 5/μL and CD8 count of 9/μL. Serum cryptococcal antigen serology was positive. MRI showed extensive posterior fossa leptomeningeal nodular enhancement and oedema causing mass effect on the fourth ventricle and early cerebellar tonsillar herniation (see figure 1). There was dilation of the third and lateral ventricles consistent with obstructive hydrocephalus. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) obtained on subsequent insertion of an external ventricular drain was positive for cryptococcal antigen.

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced axial T1-weighted magnetic resonance image showing extensive left cerebellar leptomeningeal enhancement associated with significant oedema, mass effect and effacement of the fourth ventricle.

Differential diagnosis

A neoplastic process was considered as a differential for leptomeningeal enhancement elicited on MRI especially in the setting of unintentional weight loss. However, reactivity to serum and CSF cryptococcal antigen subsequently confirmed the diagnosis of an opportunistic fungal infection.

Treatment

Antifungal therapy with liposomal amphotericin B (4 mg/kg per day) and flucytosine (25 mg/kg 6 hourly) was commenced immediately on diagnosis of cryptococcal antigen in the patient’s serum. An external ventricular drain (EVD) was subsequently inserted on an urgent basis following the patient’s clinical deterioration. This remained in situ while the patient’s symptoms and neurological status improved before being converted to a ventriculoperitoneal shunt 7 days later. After 30 days of induction antifungal therapy, the patient proceeded to consolidation therapy with 2 months of 800 mg oral fluconazole and planned maintenance therapy with 200 mg oral fluconazole for 12 months. Fingolimod was discontinued and transitioned to subcutaneous copaxone injections.

Outcome and follow-up

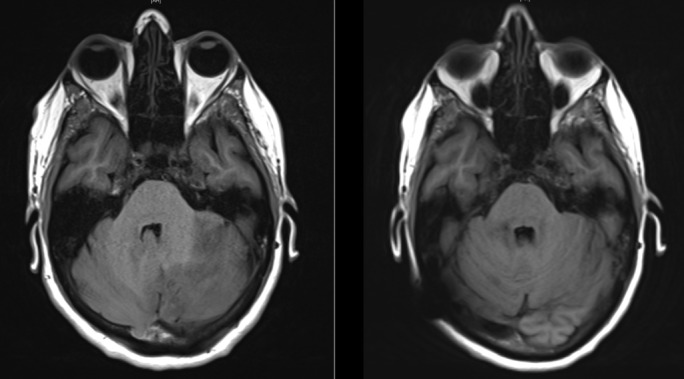

MRI neuroimaging at 6 weeks’ follow-up showed improvement of the previous posterior fossa mass effect with re-expansion of the fourth ventricle and reduction in size of the third and lateral ventricles (see figure 2). However, the patient developed new urinary incontinence with new subcortical signal changes including the right and left superior frontal gyri on MRI. Differentials included a relapse of demyelinating disease or immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Her symptoms improved following treatment with a weaning regimen of intravenous and oral steroids. This delicate balance highlights the complexities in the novel management of multiple sclerosis.

Figure 2.

Axial T1-weighted magnetic resonance image showing improvement in posterior fossa mass effect from presentation (left) to 6 weeks later (right) following medical and surgical therapy.

Discussion

This case is unique in that it is the first in the available literature to describe fourth ventricular compression and hydrocephalus resulting from extensive CNS cryptococcosis secondary to fingolimod therapy. Malignancies, reactivation of viral infections and opportunistic infections in patients on fingolimod therapy have been described in scant case reports emerging in recent years.2–5 While early evidence is notable for showing a reasonable safety profile for fingolimod, it is expected that further recognition of potentially serious complications will arise with increasing and more prolonged use of this oral immunomodulating agent. Cryptococcal meningitis in the developed world is rare and limited to immunocompromised populations such as patients with multiple sclerosis receiving fingolimod. Infection by this encapsulated yeast organism, Cryptococcus neoformans, is the most common life-threatening opportunistic fungal CNS infection.

While raised intracranial pressure with or without hydrocephalus is recognised as a potential sequelae of the chronic stages of CNS cryptococcosis, acute obstructive hydrocephalus is very rare.6 The exact mechanism of chronic CSF outflow dysregulation remains uncertain and is postulated to result from chronic inflammation of the basal meninges and possible arachnoid villi obstruction. Acute mass effect obstruction from a discrete parenchymal or leptomeningeal lesion is extremely uncommon.

Hydrocephalus can present with headache, vomiting, decreased conscious state, ataxia and visual symptoms such as diplopia and transient visual obscurations. Evidently, these can overlap with meningoencephalitis, making it difficult to distinguish between the inflammatory process of cryptococcal infection and ventricular obstruction. In cases such as this where neuroimaging has identified the presence of a dilated ventricular system, we advocate that ventricular decompression is indicated especially if there is deterioration in the patient’s condition despite initiation of medical therapy.

The timing of ventricular shunting with the stage of cryptococcal infection remains subject to debate. Active CNS infection has previously been reported to be a relative contraindication to shunt insertion as early shunt malfunction, prevention of mycological cure and seeding infection to the peritoneal cavity were described as theoretical risks.6 7 However, these events have alternatively been reported to be unlikely to eventuate and early CSF diversion has in fact been recommended to avoid development of irreversible neurological complications of raised intracranial pressure.7 Following multidisciplinary discussion within our institution and review of the available literature, we proceeded to insertion of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt 7 days after insertion of the temporary external ventriculostomy as a balance between reasonable duration of antifungal therapy and the increasing risk of EVD infection with prolonged external CSF drainage in an immunocompromised patient.

No clear guidelines exist in either the medical or surgical management of cryptococcal meningitis specific to the setting of fingolimod immunosuppression. Diagnostic considerations include serum culture and cryptococcal serology, neuroimaging and, most critically, CSF sampling for microscopy, culture and antigen testing. Detectable cryptococcal antigen in both serum and CSF confirmed the diagnosis of cryptococcosis in our case. Although no cryptococcal organisms were identified on India Ink stain or cultured from CSF samples, we note that CSF was collected (through insertion of an EVD) after the institution of antifungal therapy, which had been commenced without delay on positive serum cryptococcal serology. Antifungal protocols can be extrapolated from regimes used for non-human immunodeficiency virus immunocompromised patients.4 Neurosurgical intervention is indicated to attain CSF when lumbar puncture is contraindicated and to relieve raised intracranial pressure with temporary and/or permanent ventriculostomy.

Learning points.

Acute obstructive hydrocephalus is a life-threatening neurosurgical emergency and is rarely witnessed in acute cryptococcal meningitis.

This is the first documented case of fingolimod immunosuppression resulting in severe central nervous system cryptococcosis and hydrocephalus requiring urgent decompression.

Symptoms of hydrocephalus and meningoencephalitis may overlap and physician vigilance is required for prompt investigation and management.

The long-term adverse effect profile of fingolimod as a disease-modifying agent in multiple sclerosis is not well understood, and further cases of opportunistic infections are likely to emerge as its utility increases.

Footnotes

Contributors: CP, IB and RJ contributed equally in the planning, literature review, conception, design, analysis and review of the manuscript. CP contributed in the acquisition of information and data, development and submission of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Kappos L, Cohen J, Collins W, et al. Fingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis: an integrated analysis of safety findings. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2014;3:494–504. 10.1016/j.msard.2014.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forrestel AK, Modi BG, Longworth S, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcus in a patient with multiple sclerosis treated with fingolimod. JAMA Neurol 2016;73:355 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.4259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Achtnichts L, Obreja O, Conen A, et al. Cryptococcal meningoencephalitis in a patient with multiple sclerosis treated with fingolimod. JAMA Neurol 2015;72:1203 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.1746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang D. Disseminated cryptococcosis in a patient with multiple sclerosis treated with fingolimod. Neurology 2015;85:1001–3. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samaraweera AP, Cohen SN, Akay EM, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: a cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder in a patient on fingolimod for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2016;22:122–4. 10.1177/1352458515597568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang LM. Ventriculoperitoneal shunt in cryptococcal meningitis with hydrocephalus. Surg Neurol 1990;33:314–9. 10.1016/0090-3019(90)90198-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park MK, Hospenthal DR, Bennett JE. Treatment of hydrocephalus secondary to cryptococcal meningitis by use of shunting. Clin Infect Dis 1999;28:629–33. 10.1086/515161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]