Abstract

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is a systemic vasculitis characterised by necrotising inflammatory changes in small-sized and medium-sized vessels and granuloma formation. It most commonly involves the kidneys and respiratory tract, but it can present with widespread manifestations involving any organ system. Rarely, it causes coronary vasculitis which can precipitate a severe cardiomyopathy. Here, we report a patient who presented in cardiogenic shock requiring vasopressors and was found to have extensive myocardial ischaemia secondary to coronary vasculitis. Further investigation led to a diagnosis of GPA, and he responded to treatment with corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide and plasmapheresis.

Keywords: cardiovascular medicine, ischaemic heart disease, vasculitis, rheumatology

Background

Coronary vasculitis is an uncommon but potentially devastating complication of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA). Due to the non-specific clinical presentation of GPA-associated cardiac disease, patients may face delayed diagnosis and treatment. Evaluation for systemic vasculitides is not ordinarily part of the workup for acute heart failure but should be considered in appropriate situations. As our patient’s coronary perfusion was compromised by local inflammatory changes rather than atherosclerotic plaque rupture, he required treatment with an anti-inflammatory regimen and plasmapheresis and would not have responded to standard treatment for an acute coronary syndrome. This case illustrates that systemic vasculitides can present with diverse clinical manifestations that may mimic more common conditions, and timely identification of the vasculitis is crucial to initiate appropriate therapy. The severity of illness seen here and within prior sparse case reports emphasises the importance of considering vasculitis in the evaluation of unexplained heart failure.

Case presentation

A 50-year-old man with a history of diabetes mellitus, chronic sinusitis and undifferentiated colitis presented to an outside hospital after a fall at home. He reported several months of worsening fatigue and generalised weakness along with a 14 kg unintentional weight loss and said he had been virtually bedridden for the 6 weeks preceding presentation. He also reported a cough productive of blood-tinged sputum for the previous 10 days. On the day of presentation he suffered a mechanical fall and was unable to rise due to right leg weakness. The remainder of his history, including social and family history, was unrevealing.

On initial evaluation, he was haemodynamically stable and his examination was notable for right leg weakness and a collapsed nasal bridge. He was found to have renal failure with a blood urea nitrogen of 88 mg/dL and a creatinine of 4.9 mg/dL, compared with a normal baseline. Chest CT revealed bibasilar ground glass opacities and consolidations as well as several poorly defined nodules throughout the lung fields. A CT of his abdomen and pelvis showed no acute abnormalities.

Inflammatory and rheumatological studies included negative antinuclear antibody and rheumatoid factor and normal complement levels. His proteinase-3 (PR3) level, the antigenic determinant of c-ANCA (anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies) class, was elevated to >8 units/mL. Taken in the context of his physical examination findings, renal failure, haemoptysis and abnormal chest CT, a diagnosis of GPA was presumed. He subsequently underwent a renal biopsy to confirm the diagnosis and while awaiting the results was treated empirically with intravenous methylprednisolone 1 g/day. His renal biopsy eventually revealed crescentic glomerulonephritis with focal pauci-immune PR3-ANCA-associated necrotising arteritis.

The day following completion of steroids, the patient developed acute-onset shortness of breath, tachycardia and hypoxia, ultimately requiring non-invasive positive pressure ventilation.

Investigations

ECG was notable for a new left bundle branch block and poor R wave progression. The patient’s serum troponin level rapidly rose to a peak of 159 ng/mL. B-type natriuretic peptide was significantly elevated at 2544 pg/mL.

A transthoracic echocardiogram showed a reduced ejection fraction of 15% to 20% and severe hypokinesis of the septum, apex, inferior wall and anterior wall as well as moderate hypokinesis of the lateral wall (video 1). Given the patient’s clinical decompensation, he was transferred emergently to our facility to cardiac catheterisation.

Video 1.

Echocardiography showing depressed biventricular ejection fraction, widespread hypokinesis and biventricular dilation.

Differential diagnosis

The patient’s initial presentation to our facility with decompensated heart failure and a significant elevation in serum troponin led to high suspicion for acute coronary syndrome. Acute myocarditis was also considered. In conjunction with his renal failure, cardiomyopathy caused by coronary vasculitis remained on the differential.

Treatment

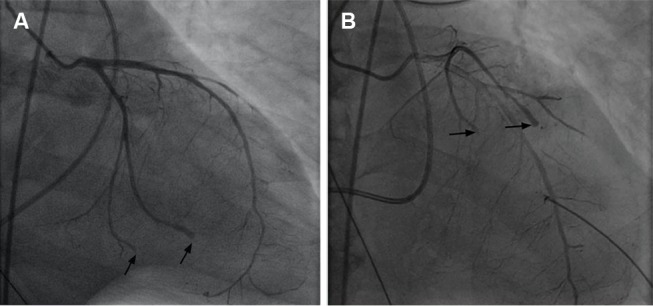

On presentation to our facility, the patient required intubation and mechanical ventilation for worsening hypoxaemia prior to cardiac catheterisation. Coronary angiography revealed a normal left main coronary artery and left anterior descending artery with cut-off of the distal portion of the diagonal. His circumflex artery showed abrupt cut-off of OM2 and OM3 (figure 1). The main portion of his right coronary artery was without disease, but there was diffuse narrowing in distal branches (videos 2 and 3). These findings were consistent with the clinical suspicion of coronary vasculitis. No atherosclerotic culprit lesion was identified.

Figure 1.

Cardiac catheterisation revealing abrupt cut-offs in the distal portions of multiple coronary vessels, consistent with embolisation or severe vasculitis.

Video 2.

Coronary angiography demonstrating abrupt cut-offs of multiple coronary vessels, but no major vessel occlusion or clear atherosclerotic lesion.

Video 3.

Coronary angiography with diffuse cut-offs of small distal branches of right coronary artery.

Right heart catheterisation revealed right atrial pressure of 12 mm Hg, right ventricular pressure of 50/12 mm Hg and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure of 25 mm Hg. His left ventricular end-diastolic pressure was 25–30 mm Hg. Cardiac output was noted to be 7.8 L/min.

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit following cardiac catheterisation and was again treated with corticosteroids with the addition of cyclophosphamide. The following morning, plasmapheresis was initiated. He remained intubated for 2 days and required intermittent vasopressor support for hypotension. After completing 3 days of intravenous methylprednisolone, he was started on a long-term prednisone taper. He underwent a total of seven plasmapheresis sessions over the 15 days after presentation to our institution.

Due to our patient’s critical illness, cardiac MRI was not obtained in lieu of empiric treatment of the vasculitis. Given the unique angiography findings in conjunction with the other systemic findings noted, the diagnosis of coronary vasculitis secondary to GPA was felt to be overwhelmingly likely, and an MRI would not have changed clinical management. Similarly, a positron emission tomography (PET)-CT was considered given a recent multicentre review demonstrating that fluorodeoxyglucose-PET/CT is highly sensitive in identifying ANCA-associated vasculitides; however, it would not have altered the management strategy we pursued given the extremely high clinical suspicion for coronary vasculitis.1

Outcome and follow-up

While the patient’s respiratory status improved and he was successfully extubated, his renal function continued to deteriorate. He eventually required haemodialysis and remains on thrice-weekly dialysis and monthly cyclophosphamide treatments, with plan to transition to rituximab on an outpatient basis.

Six weeks after his hospitalisation, a repeat echocardiogram revealed modest improvement in the left ventricular ejection fraction to 25%. He remains on a beta-blocker but has not started an ACE inhibitor or diuretic due to low blood pressure. He has an external defibrillator and is being considered for an implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

Discussion

Cardiac involvement in GPA is uncommon, although its exact prevalence remains unclear.2–4 Despite its rarity, a wide range of cardiovascular complications have been described in patients with GPA, including pericarditis, cardiomyopathy, coronary arteritis, conduction abnormalities and valvular disease.2 5 6 In a large-scale retrospective review, Walsh et al7 reported that 5.7% of 535 patients with newly diagnosed GPA had cardiovascular clinical findings, and that these patients had a significantly higher rate of disease relapse than patients without cardiac disease. Separately, McGeoch et al2 found that 3.3% of patients with GPA had associated cardiac findings; the most common manifestations were pericarditis and cardiomyopathy, while only two patients in the cohort (0.4%) had coronary artery involvement. All patients with cardiac disease in this series presented with cardiopulmonary symptoms, including chest pain, dyspnoea and syncope; these patients did not have higher rates of mortality or disease relapse.

While cases of cardiac involvement in GPA are not exceedingly rare, there are only sparse reports of severe coronary vasculitis or cardiogenic shock secondary to GPA. Unusually, our patient presented with decompensated heart failure and a significant elevation of his troponin, reflecting widespread myocardial damage secondary to coronary occlusion. Coronary vasculitis in GPA can have devastating clinical consequences. Shah et al8 describe a patient who presented with recurrent ST-elevation myocardial infarctions, with coronary angiography revealing evolving areas of coronary occlusion consistent with a vasculitic process. She was also found to have elevated c-ANCA level with strong positivity against PR3 antigen, but unfortunately died while pursuing optimal therapy. A similar case described by Lawson et al9 involved a young man with GPA who died from cardiogenic shock and acute myocardial infarction related to vasculitic changes.

Given the rapid and catastrophic decline such patients may have, the clinician must be mindful of this presentation of coronary vasculitis and pursue appropriate treatment of the vasculitis expeditiously. In our case, thorough evaluation and examination revealing mononeuritis multiplex, saddle nose deformity, acute kidney failure and acute respiratory failure allowed for quick diagnosis so that appropriate therapy could be initiated.

Learning points.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) has a wide range of clinical manifestations and can involve organ systems other than the kidneys and respiratory tract.

Coronary vasculitis in the setting of GPA can provoke myocardial ischaemia and acute heart failure; vasculitides should be considered in the differential for unexplained cardiac disease when appropriate.

Myocardial ischaemia from coronary vasculitis is treated with high-dose glucocorticoids, cyclophosphamide and plasmapheresis and will not respond to usual treatment for acute coronary syndrome. The progression of disease may be severe and fatal.

Footnotes

Contributors: VR was involved in the planning, outline, background research including literature review and writing of this manuscript. He also edited and formatted the document and incorporated images. AP took part in the planning and background research for the paper and wrote sections of the manuscript. He also acquired and reviewed the cardiac catheterisation images. DG was involved in the planning and literature review for this paper, writing of the manuscript and editing and revision prior to submission. GC played a role in the planning and organisation of the project, acquisition of patient data and revision of the manuscript. All four physicians above were involved in the care of this patient.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Soussan M, Abisror N, Abad S, et al. . FDG-PET/CT in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis: case-series and literature review. Autoimmun Rev 2014;13:125–31. 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGeoch L, Carette S, Cuthbertson D, et al. . Cardiac involvement in granulomatosis with polyangiitis. J Rheumatol 2015;42:1209–12. 10.3899/jrheum.141513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miloslavsky E, Unizony S. The heart in vasculitis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2014;40:11–26. 10.1016/j.rdc.2013.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hazebroek MR, Kemna MJ, Schalla S, et al. . Prevalence and prognostic relevance of cardiac involvement in ANCA-associated vasculitis: eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis and granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Int J Cardiol 2015;199:170–9. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.06.087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliveira GH, Seward JB, Tsang TS, et al. . Echocardiographic findings in patients with Wegener granulomatosis. Mayo Clin Proc 2005;80:1435–40. 10.4065/80.11.1435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dewan R, Trejo Bittar HE, Lacomis J, et al. . Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis presenting with coronary artery and pericardial involvement. Case Rep Radiol 2015;2015:1–5. 10.1155/2015/516437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walsh M, Flossmann O, Berden A, et al. . Risk factors for relapse of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:542–8. 10.1002/art.33361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah AH, Kinnaird TD. Recurrent ST elevation myocardial infarction: what is the Aetiology? Heart Lung Circ 2015;24:e169–e172. 10.1016/j.hlc.2015.04.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawson TM, Williams BD. Silent myocardial infarction in Wegener's granulomatosis. Br J Rheumatol 1996;35:188–91. 10.1093/rheumatology/35.2.188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]