Abstract

A young amateur wrestler presented with a burst fracture of the seventh cervical vertebra with complete paraplegia. He was treated with surgery for spine stabilisation and was actively rehabilitated. Adolescents and teenagers are indulging in high-contact sports like wrestling, without proper training and technical know-how, which can lead to severe injuries and possibly, permanent handicap or death. Trainers, assistants and institutions should be well equipped to diagnose and provide initial care of people with a spinal injury to prevent a partial injury from progressing to complete injury. Athletes, coaches and the public should be aware of methods of first aid and how to transport a patient with a cervical spine injury. Authorities should take steps to improve infrastructures in training institutions and ambulance services. Specialised spinal centres should be established throughout the country for management and rehabilitation of patients with paraplegia.

Keywords: trauma, spinal cord, orthopaedics, physiotherapy (sports medicine)

Case presentation

A 19-year-old male was brought to our emergency department with pain in the neck, inability to move both lower limbs and lack of sensation in the lower half of the body. He had been practising wrestling with a friend and fell onto his head with his opponent falling on top of him. He developed sudden onset pain in the posterior aspect of the neck and was unable to move both lower limbs. He was taken to hospital by car in sitting position, and after an X-ray examination and CT scan was referred to our institute with a Philadelphia Collar in the supine position. He reached our institute 9 hours after his injury. He was diagnosed as having a C7 burst fracture (figure 1), with complete paraplegia of the lower limbs with an American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) grade A on the ASIA Impairment Scale. Gardner-Well tongs skull traction was applied and treatment was started with methylprednisolone at a dose of 30 mg/kg bolus over 15 min and then as an infusion at the rate of 5.4 mg/kg/hour for 23 hours beginning 45 min after the bolus. Anterior corpectomy, stabilisation and fusion were carried out through the anterior approach to stabilise the spinal segment. Postoperative X-ray examinations were satisfactory (figure 2) and the postoperative period was uneventful.

Figure 1.

(A) The burst fracture of C7 vertebra in the CT sagittal section view of the cervical spine; (B) the CT axial section with fracture of C7 and retropulsion of the fragment in the canal.

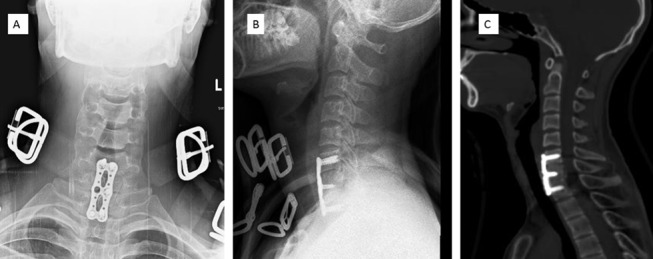

Figure 2.

(A, B) The postoperative anteroposterior and lateral view of the C spine with the implant in situ. (C) The CT sagittal section of the cervical spine after stabilisation with the implant in situ.

He received continuous intermittent catheterisation, and regular physiotherapy for the lower limbs, and back care to prevent pressure sores (decubitus ulcer) due to lack of sensation. He received counselling from a psychiatrist and clinical psychologist to prevent depression and reduce his mental distress. A custom-made spinal orthosis with an extended cervical collar was made to support his cervical spine. After application of the spinal orthosis, the Gardner-Well traction was removed at 3 weeks, and he was discharged. Details of back and spine care and continuous intermittent catheterisation were taught to those who would assist him. He came to us after 1 month with a decubitus ulcer over the sacral region (figure 3), for which wound debridement and a rotational flap were provided. He was admitted for wheelchair mobilisation at 3 months after surgery and remains in a wheelchair. No signs of neurological recovery were seen at 6 months' follow-up.

Figure 3.

A stage four decubitus ulcer over the sacral region.

Social and personal history of the child

The patient was a college student with a healthy personal and social life before the injury. His aim was to get a government job or to become a charted accountant and start a private tax consultancy. He had begun to learn wrestling in the past 2 months. He used to receive ‘Kushti’ training with his friends at college and nearby training centres after the college hours. However, he was not receiving regular, systematic training and a coach was not present when he was injured. He had developed an interest in wrestling from watching local tournaments, and owing to the recent popularity of Olympic wrestlers in India. He was also inspired by the movie ‘Dangal’ based on the biopic of Indian wrestler Geetha Kumari Phogat. However, he did not know all the grips and techniques as he had started practising only recently and had no information about the types of possible serious injuries.

After the injury, he developed paraplegia and was confined to a wheelchair and looked after by his father and brother. No signs of depression were seen during the initial hospital administration period. However, he was less optimistic at 6 months' follow-up as there was no evidence of neurological recovery. He has not yet restarted at college but is planning to do this in the coming month.

Global health problem list

A distressing increase in the number of adolescents and young people involved in contact sports without proper training or know-how.

Lack of awareness among rural youth about the injuries which can be sustained from high-contact sports.

Lack of infrastructure, education and trained coaches and medical personnel involved in contact sports.

Ignorance of those in primary care about transportation of a patient with cervical spine injury.

Lack of specialised centres of excellence in spine injury management in the country.

High morbidity and poor quality of life in patients with paraplegia and quadriplegia.

Global health problem analysis

History and popularity of wrestling in India

Wrestling is one of the oldest forms of combat sports in the world, referred to in many ancient books and illustrations. It has been depicted in the cave drawings in France from 15 000 years ago. Wrestling has also been mentioned in Homer's Iliad, ancient Greek and Egyptian literature. In India, wrestling as a means of sport and combat dates back to the Vedic period. The great Indian epics, Mahabharata and Ramayana, give details of many wrestling battles called ‘Dhwandha Yudha’ and ‘Malla Yudha.’ Indian wrestling belongs to a type of folk wrestling. This is a form of traditional wrestling belonging to a particular region or culture for which the rules may not be standardised by the International governing body for wrestling—United World Wrestling (UWW). Six wrestling disciplines are recognised by UWW: male and female freestyle wrestling, Greco-Roman wrestling, amateur pankration, beach wrestling and belt wrestling.1 The popularity of wrestling in India has skyrocketed in recent years owing to the success of many of the Indian wrestlers in international competitions—for example, the 2014 Commonwealth games at which Indian wrestlers won five gold, six silver and two bronze medals.

Catastrophic cervical spine injury

The spectrum of spinal injuries in sports encompasses cervical sprains/strains, brachial plexus injuries, cervical spinal stenosis, intervertebral disc prolapse or cervical fracture and dislocations. A catastrophic cervical spinal cord injury occurs with structural distortion of the cervical spinal column and is associated with actual or potential damage to the spinal cord.2 If the level of spinal injury is above C5, there is a risk of sudden death for the athlete due to the inability to transmit respiratory or circulatory control from the brain. The spinal injury can be a complete or incomplete injury. ASIA has defined the extent of spinal cord injury using an impairment scale.3

ASIA A—Complete injury. No motor or sensory function in sacral segments S4–S5.

ASIA B—Incomplete injury. Sensory, but not motor, function is preserved below the neurological level.

ASIA C—Incomplete injury. Motor function is retained below the neurological level, and most key muscles below the neurological level have a muscle power of <3.

ASIA D—Incomplete injury. Motor function is preserved below the neurological level, and most key muscles below the neurological level have a muscle power that is ≥3 (useful motor power).

ASIA E—Sensory and motor function is normal.

The term quadriplegia refers to impairment or loss of motor and sensory function in the cervical segments of the spinal cord owing to damage to neural structures within the spinal canal, leading to impairment of function in the upper limb, lower limb, trunk and pelvic organs. Tetraplegia results in impairment of function in the arms and in the trunk, legs and pelvic organs.3

The term paraplegia refers to impairment or loss of motor and sensory function in the thoracic, lumbar or sacral segments of the spinal cord. In paraplegia the upper limb function is spared, but the trunk, lower limbs and pelvic organs may be involved depending on the level of injury.3

Lack of awareness among young athletes about possible injuries in high-contact sports

According to the latest report by the WHO, between 250 000 and 500 000 people have a traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) every year.4

Traumatic paraplegia occurs most often among young men between the ages of 21 and 35 years, and therefore it is considered to be a social problem that affects part of the economically active population.5 According to WHO, 20–40 individuals per million of population acquire a SCI each year and 82% of them are male, with 56% of injuries occurring between the age of 16 and 30 years.5

Two decades ago, SCIs constituted only 2–3% of sports-related injuries overall.6 However, recent studies have shown that it now accounts for up to 9% of the total injuries.7 In the developed countries, sports injuries are the second most common cause of spinal injuries in the first three decades of life.8 Seven per cent of all new spinal injuries in the USA are due to sports-related injuries.9 The incidence of sports-related spinal injuries in Japan is 1.95 per million per year.10

No spinal injury registry is available in India to calculate the incidence and severity of injuries11 and no data are available on sports-related injuries, including spinal injuries, in India. There is a recent resurgence of many sports like badminton, football, etc, but there are also many other high-contact sports which have gained popularity in India, such as wrestling and Kabaddi, for which the youth in most geographical regions receive insufficient training at the start of their career. It is in the early part of their career that athletes in contact sports like wrestling are more prone to injury. Strauss and Lanese assessed the pattern of injuries in wrestling during several tournaments and found that the younger wrestlers (8–14 year-olds) were injured at a rate of 3.78/100 tournament participants, whereas for high-school wrestlers the rate was 11.15/100.12

Most athletes are not taught the proper techniques of the sport for injury prevention and discontinue the sport after injuries early in their career. Only the most talented receive structured training from professional coaches. Most amateur athletes are unaware of the anatomy of their body and the severe injuries which can occur during training or competitions.

Lack of infrastructure, education and trained coaches and involvement of medical personnel in contact sports

Most wrestlers in India achieve their initial training in the sport from teachers called ‘gurus’ at specific places called ‘Akhadas.’ Most of these teachers are veteran wrestlers who start coaching when their wrestling career ends. Even though many of these teachers are skilled wrestlers who are well versed in their craft, they lack the training to diagnose an injury early and provide effective first aid during an emergency. In the urban area, it is mainly the schools and colleges which provide training for wrestling competitions. In many such educational institutions, a single instructor provides training in all the sports and games in the institution, and in some there is no proper training infrastructure. Most training institutions in India have no medical or paramedical support staff to provide fiirst aid or resuscitation during an emergency. Such a gap in grass root level training results in early injuries to the athletes, some of which are severe and end an athlete's career in sports.

Ignorance of the initial care and transportation of a patient with cervical spine injury

Until quite recently, the importance of expert rescue and first aid in cervical spine injuries was not realised. The consequences of inappropriate manipulation of the neck or of trying to make an injured person stand up can convert an incomplete spinal cord injury into a complete injury. An analysis of post-traumatic paraplegic patients in India by Pandey et al observed that the primary modes of transport of a patient with SCI vary but most do not include an ambulance or other expert services.13 The means of transportation include cars, auto rickshaw, bullock carts and scooters. The ambulance service for the transport of patients to hospital was used for only 25% of patients. Ignorance of the precautionary steps needed to prevent neurological deterioration during transport of patients with cervial spine injury was found in 82% of cases.

Delay in presentation to the hospital

In India, there is often a delay in presentation of patients with SCI to hospital., owing to a lack of knowledge among relatives about the seriousness of the injury, and lack of knowledge of medical and paramedical staff in hospitals in rural areas. The study by Pandey et al observed that patients with spinal injury are moved between an average of at least two hospitals before coming to specialised spinal units.13 Air transport of patients with spinal injury which is available in many developed countries, is almost non-existent in India owing to the huge population, lack of funding and insufficiency of spinal care centres.

According to Lalwani et al the place of first medical encounter is decided more often by the relatives, bystanders and police, and in most instances is the closest medical facility, which may be grossly inadequate to deal with serious trauma.11

Lack of specialised centres of excellence in spine injury management in the country

In a vast country like India the number of specialised centres of excellence in spine injury management is inadequate. In most developed countries, the rehabilitation of paraplegic patients is one of the most important goals of treatment.

There is a demand for specialised spinal trauma centres across the country, accessible to people from all strata of society, for global management of spinal cord injuries. Proper coordination between the peripheral primary care centres and the spinal care centres is required. Additionally, associated medical, and paramedical personnel should be adequately trained in first aid and the transport of patients with spinal injury.

Rehabilitation and quality of life

Most patients with spinal cord injury are typically physically active young men belonging to the earning population. A severe spinal injury can affect the socioeconomic balance in the family.

The quality of life of paraplegics and quadriplegics is much reduced as compared with that of normal individuals. Catastrophic spinal injuries cause high mortality and morbidity. The most famous example is Christopher Reeve, the American actor who portrayed Superman in the movies. He became a quadriplegic in 1995 after an injury to the cervical spine after falling from a horse and was later confined to wheelchair and needed a portable ventilator. In 2002 he started the Christopher and Dana Reeve Paralysis Resource Centre, which promoted stem cell research for SCI and rehabilitation of patients with SCI. He died at the age of 52 from cardiac arrest following sepsis from an infected decubitus ulcer. According to Middleton et al who conducted a 50-year analysis study involving 2014 patients with SCI, 88 people with tetraplegia (8.2%) and 38 individuals with paraplegia (4.1%) died within the first year.14 Among the patients who survived the first year, overall 40-year survival rates were 47% and 62% for people with tetraplegia and paraplegia, respectively.14

According to the study by Kemp and Krause, 41% of patients with spinal injury had significant depressive symptoms compared with only 22% of people with polio and and 15% of non-disabled people.15

Management of patients with SCI in spinal units with dedicated experts for comprehensive rehabilitation improves the outcome.16 Studies have shown that patients with spinal injury presenting early to a specialised spine centre have a better functional outcome after rehabilitation than patients presenting late.17

Studies have emphasised the need to bring together patients with SCI into regional spinal units.16

We have observed that many paraplegic and quadriplegic patients respond very well to the care as long as they are in hospital. After discharge to home, the quality of care for the patient deteriorates, and complications develop as family members become busy with their own occupations. This happened to our patient who developed a pressure sore 1 month after discharge from the hospital.

Countries such as Australia provide ‘extended spinal care’, in which healthcare professionals visit the patients with spinal injury at their home and give medical help, detect complications and aid in rehabilitation. Prabhaka et al in their study discussed a home visit programme for patients with SCIs conducted in Ahmedabad, India and observed that it reduced the number of readmissions by improving the quality of care for patients.18 According to Chappell et al, 50–60% patients with an SCI remain unemployed after injury.19

Patients with a spinal injury should be treated by a comprehensive rehabilitation team consisting of a doctor, nurse, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, psychologist, prosthetic and orthotic engineer and a social worker. The government should take steps to aid the rehabilitation of these disabled patients. Rehabilitation schemes and house visits can be integrated into national programmes to maximise the benefit, including health education, providing wheelchairs, job reservations and pension.

Recommendations for prevention and management of acute SCIs in athletes

The National Athletic Trainers Association has published a position statement providing recommendations to trainers and emergency healthcare professionals for the prevention and management of potentially catastrophic cervical spine injuries.2 20 21 The important recommendations are

Coaches and emergency care personnel (ECP) should be familiar with safety rules for prevention of cervical injuries and should ensure that the rules are strictly followed.

Coaches and ECP should be aware of the specific causes of cervical spine injury and the mechanism of these injuries in contact sports.

Coaches and athletes should be educated about the rules for preventing spinal injuries, such as avoiding spearing during tackles, protecting the head during tackles and fall, etc.

Athletes, trainers and ECP should be well versed in the use, maintenance and care of protective sports gear.

An emergency action plan (EAP) should be formulated before every sports event. The EAP should have a team leader in charge of the training, and practice of skills in managing a spinal injury. Adequate equipment for spinal stabilisation and transport of victims should be arranged. The EAP should be known to the local authorities and hospitals before the event so that adequate facilities are arranged.

Regular training drills and practice sessions should be conducted for ECP to improve their skills and coordination on manual head stabilisation, patient immobilisation, securing airway access, transfer to the health facility, etc.

Loss of consciousness, midline cervical pain or tenderness, spinal deformity and neurological deficits are indicators of potential cervical spine injury. In such situations, the spinal injury EAP should be activated. The cervical spine should be kept in a neutral position. Traction of the cervical spine should be avoided.

The airway should be secured by the most experienced person and rescue breathing should be provided. Advanced airway management techniques can be used if trained rescuers are present.

A spine board or other equipment which immobilises the whole body should be used for transport of the injured athletes. Transferring the athlete to these devices can be done by the log roll technique or lift and slide technique. A rigid collar, such as the Philadelphia Collar, should be placed before moving the patient to the spinal board.

Removal of athletic gear from the athlete’s body should ideally be delayed until the victim reaches the hospital or other medical facility. This is to avoid aggravating the injury to the cervical spine. An exception to this rule is when the sports equipment prevents the cervical immobilisation and proper alignment of the spine, or face masks are present which interfere with airway access during resuscitation. The emergency care providers should be aware of the equipment parts and the techniques for their removal.

The coach or team doctor should accompany the injured person to the hospital.

If a catastrophic cervical spine injury is suspected, a CT scan is better than a plain X-ray examination as the primary diagnostic investigation in athletes who have sports gear and helmet in situ.

Patient’s perspective.

During initial hospital stay

"I came to know that I had a fracture in my neck and due to that, my spinal cord got damaged. I landed on my neck while playing with my friend on the wrestling mat and my friend lost balance and fell on top of me. I am not able to feel anything beyond by abdomen and I am not able to move my legs. I also have some tingling in my right little finger and hand. The doctor has told that such type of injury has only little chance of recovery’. The prospect of not able to walk and lead a normal life terrifies me. I am only 19 years old, and I want to get well. I am praying to God and I am leaving everything on my God."

At 6 months' follow-up

"I have no pain in my neck now, and I can use the wheelchair. There is no neurological improvement even now. My hopes of walking are slowly fading. I feel sad and helpless at times but my family gives me strength. They take care of me. I don't feel my bowel and bladder and have to seek help for all my activities. I lie down in bed most of the time watching television. I cannot go out with my friends. Only my close friends come and visit me once in a while. My life has changed totally, and it won't be the same ever. I wish to continue my studies and attain my degree. I have read a lot about spine injuries and now realise the mistakes done by people like me. It was an accident, but who knows….maybe it could have been avoided."

Learning points.

Coaches and athletes should be educated about spinal injuries and their mechanism, recognition of injuries and preventive measures to minimise cervical spine injuries.

Spinal injuries should be ruled out in contact sports injuries with unconsciousness or altered level of consciousness, neurological deficits, significant midline spine pain or tenderness, or an obvious spinal column deformity.2

Athletes, coaches and supporting staff should be well versed in manual cervical spine stabilisation techniques. They should also be taught to establish the airway, breathing and providing cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

A long spine board and hard cervical collars should be made readily available in institutions which provide coaching in contact sports like wrestling.

Government and authorities should take measures to rehabilitate the athletes with spinal injuries to help them lead a dignified life.

Necessary steps must be taken to improve ambulance services, establish spinal centres across the country and create and maintain spinal injury registers nationally and monitor the quality of data collected.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to conception and design of the paper. JKNK acquired the data and drafted the article. RJ acquired the data. SPM corrected the final manuscript, and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.United World Wrestling. https://unitedworldwrestling.org/disciplines (accessed 15 Feb 2017).

- 2.Casa DJ, Guskiewicz KM, Anderson SA, et al. National athletic trainers' association position statement: preventing sudden death in sports. J Athl Train 2012;47:96–118. 10.4085/1062-6050-47.1.96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ditunno JF, Young W, Donovan WH, et al. The international standards booklet for neurological and functional classification of spinal cord injury. American Spinal Injury Association. Paraplegia 1994;32:70–80. 10.1038/sc.1994.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hagen EM. How to prevent early mortality due to spinal cord injuries? New evidence & update. Indian J Med Res 2014;140:5–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalyani HH, Dassanayake S, Senarath U. Effects of paraplegia on quality of life and family economy among patients with spinal cord injuries in selected hospitals of Sri Lanka. Spinal Cord 2015;53:446–50. 10.1038/sc.2014.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maroon JC, Bailes JE. Athletes with cervical spine injury. Spine 1996;21:2294–9. 10.1097/00007632-199610010-00025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical center. Spinal Cord Injury (SCI)Facts and Figures at a Glance. https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/Public/Facts_2016.pdf (accessed 25 Apr 2017).

- 8.Nobunaga AI, Go BK, Karunas RB. Recent demographic and injury trends in people served by the Model Spinal Cord Injury Care Systems. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999;80:1372–82. 10.1016/S0003-9993(99)90247-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mueller FO, Cantu RC, Van Camp SP, et al. Catastrophic Injuries in High School and College Sports. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Sport Science Monograph Series, 1996:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katoh S, Shingu H, Ikata T, et al. Sports-related spinal cord injury in Japan (From the nationwide spinal cord injury registry between 1990 and 1992). Spinal Cord 1996;34:416–21. 10.1038/sc.1996.74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lalwani S, Singh V, Trikha V, et al. Mortality profile of patients with traumatic spinal injuries at a level I trauma care centre in India. Indian J Med Res 2014;140:40–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strauss RH, Lanese RR. Injuries among wrestlers in school and college tournaments. JAMA 1982;248:2016–9. 10.1001/jama.1982.03330160064026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pandey V, Nigam V, Goyal TD, et al. Care of post-traumatic spinal cord injury patients in India: an analysis. Indian J Orthop 2007;41:295–9. 10.4103/0019-5413.36990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Middleton JW, Dayton A, Walsh J, et al. Life expectancy after spinal cord injury: a 50-year study. Spinal Cord 2012;50:803–11. 10.1038/sc.2012.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kemp BJ, Krause JS. Depression and life satisfaction among people ageing with post-polio and spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil 1999;21:241–9. 10.1080/096382899297666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nwadinigwe CU, Iloabuchi TC, Nwabude IA. Traumatic spinal cord injuries (SCI): a study of 104 cases. Niger J Med 2004;13:161–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scivoletto G, Morganti B, Molinari M. Early versus delayed inpatient spinal cord injury rehabilitation: an Italian study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005;86:512–6. 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prabhaka MM, Thakker TH. A follow-up program in India for patients with spinal cord injury: paraplegia safari. J Spinal Cord Med 2004;27:260–2. 10.1080/10790268.2004.11753758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chappell P, Wirz S. Quality of life following spinal cord injury for 20-40 year old males living in Sri Lanka. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal 2003;14:162–78. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swartz EE, Boden BP, Courson RW, et al. National athletic trainers' association position statement: acute management of the cervical spine-injured athlete. J Athl Train 2009;44:306–31. 10.4085/1062-6050-44.3.306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Athletics Trainers Association. Appropriate Prehospital Management of the Spine-Injured Athlete Updated from 1998 document. http://www.nata.org/sites/default/files/executive-summary-spine-injury-updated.pdf (accessed May 2017).