1. BACKGROUND

The medical and social context of prostate cancer (PCa) has changed dramatically since the introduction of PSA testing for early detection in the late 1980s,1 leading to a peak in incidence in the developed world in the 1990s and again a decade later.2 Since that time, novel PCa treatments have rapidly emerged in the radiation and medical oncology field, as well as surgical advances.3 The recent emergence of active surveillance for low‐risk disease has further expanded possible treatment approaches.4 Market forces from consumers, clinicians, and the therapeutic industry have driven changes in clinical and surgical management and treatment; however, psycho‐oncological research and survivorship care arguably has lagged behind. Specifically, although men are surviving longer, they may not be surviving well. In 2012, there were over 1.1 million incident cases of PCa diagnosed and more than 300 000 deaths worldwide.5 Five‐year prevalence estimates suggest that there are over 3.8 million PCa survivors globally6 with this expected to increase rapidly in future.7 The challenges we face in meeting the needs of these men and their families into the future are vast.

Up to 75% of men treated for localised PCa report severe and persistent treatment side‐effects including sexual dysfunction, poor urinary or bowel function.8 Psychosocial concerns are prevalent with 30%‐50% of PCa survivors reporting unmet sexuality, psychological, and health system and information needs9, 10 and 10%‐23% of men clinically distressed.11 Risk of suicide is increased after PCa diagnosis12, 13 and can persist for a decade or more.14 In the longer term, 30%‐40% of PCa survivors report persistent health‐related distress, worry, low mood15 and diminished quality of life (QoL).16 Partners of PCa survivors also experience ongoing psychological concerns and changes in their intimate relationships17; with these impacts driven in part by the man's level of distress, sexual concerns and physical QoL.18

In 2011, our group published the first criterion‐based systematic review of psychosocial interventions for men with PCa and their partners.19 We concluded that group cognitive‐behavioural interventions and psycho‐education appeared to be helpful in promoting better psychological adjustment and QoL for men with localised PCa, and coping skills training for female partners may improve their QoL. However, data were limited by inconsistent results and low study quality. In response to the increasing burden of PCa, uncertainties about optimal psychosocial care, and additions to the literature, we updated and extended this review with the intent of determining benefit and acceptability, and considering intervention content and format. In brief, we considered the range of psychosocial and psychosexual interventions that may be optimal, and for whom.

2. METHODS

Two clinical questions guided the review20: In men diagnosed with PCa (Q1) and/or in their partners/carers (Q2), what is the effectiveness of different psychosocial or psychosexual interventions compared with (i) other psychosocial or psychosexual interventions, or (ii) usual care or no intervention, in maintaining or improving QoL or psychological wellbeing? Psychosocial or psychosexual interventions were included if they had one or more of the following components: education (psycho‐education, psycho‐sexual education, PCa education), cognitive‐behavioural (cognitive restructuring, behaviour change, cognitive‐behavioural stress management), relaxation (relaxation techniques, meditation), supportive counselling (counselling/psychotherapy, health professional discussion), peer support (peer support, social support including discussion within a group of peers), communication (skill development to encourage communication with partners, health professionals or generally) and decision support (aids or tools to assist decisions about PCa treatment or use of sexual aids). The review and reporting of results were guided by the PRISMA statement.21 Ethical approval was not required.

2.1. Search strategy

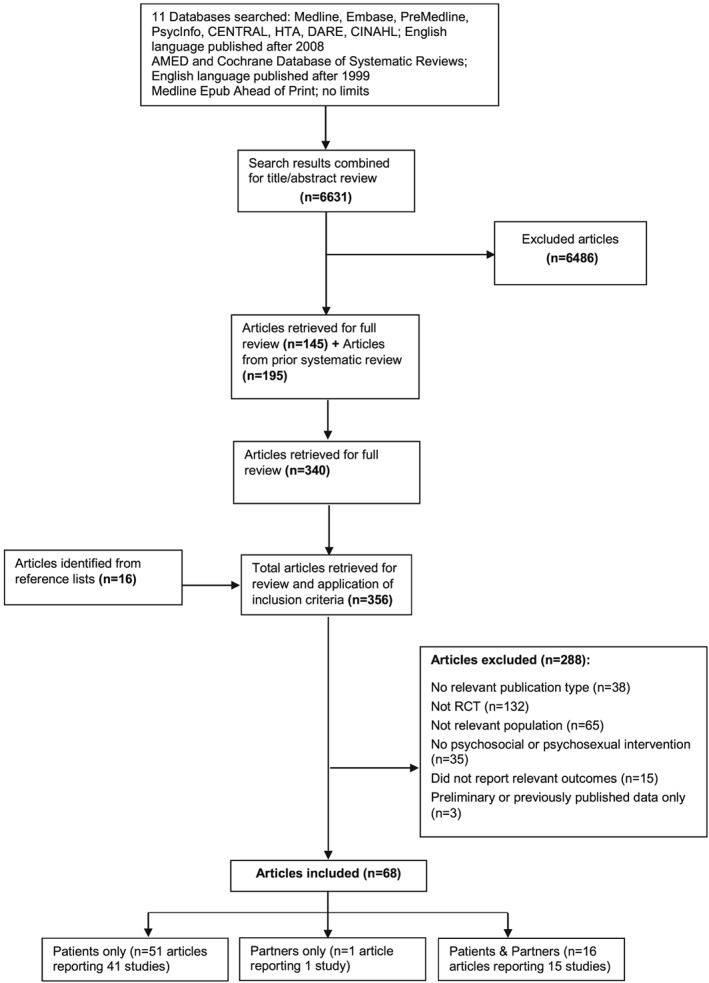

Our prior review (until December 1, 2009) identified 195 articles that met criteria for the current study.19 Searches were updated from 2009 onwards. Eleven relevant databases were searched (eg, MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, and CINAHL; Figure 1) up to January 9, 2017. Free‐text terms and database‐specific subject headings for PCa and psychological and QoL outcomes were used (Appendix A shows full search strategies). Reference lists of included articles were also searched. ClinicalTrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov/) (June 2016) and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/) (October 2016) were searched for ongoing and completed trials and associated publications.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection for systematic review

2.2. Selection criteria

Studies were included if the following pre‐specified criteria were met:

Randomised controlled trial design.

≥80% of participants were men diagnosed with PCa (no restrictions on disease stage or time since diagnosis) and/or partners/carers of men with PCa or results for men with PCa and/or partners/carers were reported separately.

Intervention(s) were psychosocial or psychosexual.

Outcome(s) reported were psychosocial (including psychological, relationships, decision‐making), health‐related QoL, and sexuality outcomes (including sexual function, bother, and use of erectile dysfunction aids or treatments). Mediator outcomes such as cognitive reframing and coping were not included.

Outcomes were assessed using validated scales or scales adapted from these.

Intervention(s) were compared with usual care or supportive attention or no intervention, and/or another intervention(s) with different psychosocial or psychosexual components, and/or the same intervention components with a different mode(s) of delivery. Multimodal interventions such as lifestyle interventions were only included if they had a psychosocial or psychosexual component.

Published in English language.

Published after December 31, 1999 up to January 9, 2017.

Two authors reviewed titles and abstracts and excluded irrelevant articles and duplicates. Full‐text articles that potentially met criteria were then retrieved and reviewed by one author. A random sample of 5% of articles was assessed for inclusion by 2 authors with 100% agreement achieved.

2.3. Data extraction

One author extracted pre‐specified study characteristics (eg, participant demographics, PCa treatments, intervention content, delivery and results) and another checked each extract. To support data extraction, published descriptions of interventions were content analysed to create a framework of common psychosocial or psychosexual intervention components (Appendix B).

2.4. Risk of bias

The Cochrane Collaboration's tool was used to assess risk of bias regarding sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel collecting outcome data, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources (eg, difference in follow‐up between arms).22 Blinding is difficult to achieve in psychological trials where consent mechanisms require participants to understand differences in treatments, which are often clearly discernible to the participant (eg, therapist‐delivered intervention vs self‐help materials).19 On this basis, blinding was excluded from assessment. Clinical trial registries at https://clinicaltrials.gov/, http://www.isrctn.com/, and http://www.anzctr.org.au/ were searched for protocols of included studies to identify pre‐specified outcomes and determine whether there was a risk of bias from selective outcome reporting. Differences in evaluations were resolved by discussion and where necessary adjudication by a third author.

2.5. Intervention acceptability

The criteria of Yanez et al23 were used to identify and evaluate aspects of interventions that indicate acceptability: ≥40% recruitment rate, ≥70% retention at end of intervention or follow‐up (or <30% withdrawal), and ≥70% average intervention attendance.

2.6. Analyses

It was anticipated that some trials may be underpowered.19 Thus, an intervention was considered potentially beneficial compared with usual care or better than another intervention if for at least one reported outcome (at the longest reported follow‐up), there was in favour of the intervention(s): (i) a statistically significant difference between arms; (ii) a moderate or large standardised effect size (eg, Cohen's d ≥ 0.5, η 2 ≥ 0.06); or (iii) a difference in mean score changes from baseline calculated by ANCOVA or multiple linear regression between arms ≥10% of the scale of the differences in means. For a given measurement scale, results from subscales were only considered in the absence of an overall score.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Search results

In all, 6631 citations were identified of which 161 full‐text (including 16 identified from reference lists) were retrieved and evaluated as well as 195 articles from the prior review.19 Of the total 356 full‐text articles assessed for inclusion, 68 articles met criteria and reported a total of 57 RCTs. Forty‐one RCTs reported in 51 articles (2 publications for 10 studies) included only patients (Q1); 1 RCT included only partners (Q2); 15 RCTs reported in 16 articles (2 publications for 1 study) included patients and partners (Q1 and Q2) (Figure 1). Most studies were excluded because of study design or population not meeting criteria, or results for patients or partners/carers were not reported. Clinical trial registry searches identified 47 trials: 25 completed (16 included in the review); 20 ongoing; 2 terminated (slow accrual, funding unavailable).

3.2. Risk of bias

Risk of bias from sequence generation (61% Q1; 64% Q2) and allocation concealment (71% Q1; 79% Q2), was unclear, and high for incomplete outcome data (43% Q1; 43% Q2) for most studies. Risk of bias from selective outcome reporting was also high for majority of partner studies (43%) and unclear for patient studies (63%). Most studies were low risk for other sources of bias (70% Q1; 86% Q2) (Appendix C).

3.3. Trial characteristics

Included trials randomised 8378 men (range 27‐740; 48% of trials had <100 participants), and 1313 partners (range 27‐263; 57% of trials had <100 participants; >90% partners were female in 14 trials; >80% partners were spouses in 12 trials). Most (67%) trials were conducted in North America. In 10 trials (4 including partners), participation was determined by socio‐demographic background (eg, African‐American), emotional state (eg, distress), or QoL (eg, urinary or sexual dysfunction, ADT treatment side‐effects, fatigue). When reported, mean or median age was below 65 years in 49% of trials for patients and below 65 years in 100% of trials for partners. In approximately half of trials (57% of patient trials, 40% of partner trials) reporting college/university education, >50% of participants were university/college educated. In 25 trials (45%), men were diagnosed with or treated for localised disease in the previous 6 months (14 trials enrolled men prior to treatment or treatment decision). Men with recurrent or metastatic disease and their partners were included in 16% and 21% of trials, respectively.

The number of relevant outcomes measured by trials varied from 1 to 16 (patient) and 2 to 12 (partner). Most common outcomes for patients were sexual bother and/or function and mental health; and for partners were relationships, general and cancer‐specific distress. Trials reported 41 patient, 1 patient and partner, and 1 partner person‐focused (targeted and delivered to the individual or person) interventions and 14 couple‐focused interventions (targeted and delivered to the couple as a dyad) (Appendix D). Most interventions were compared with usual or standard care; however, what the comparison group entailed was rarely described. Follow‐up ranged from immediately post‐intervention to approximately 19 months (person‐focused, Median = 3 months) or 12 months (couple‐focused, Median = 6 months) post‐intervention.

3.4. Intervention acceptability

Trials comprising interventions that were person‐focused were more acceptable than couple‐focused interventions (recruitment: 72% vs 29%; retention: 74% vs 64%). Approximately 40% of person and couple interventions indicated acceptable mean attendance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Acceptability of included trials comprising person‐ (n = 43) and couple‐ (n = 14) focused interventions

| Acceptability category | Person* N (%) | Couple N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Recruitment | ||

| No: <40% | 8 (19%) | 6 (43%) |

| Yes: ≥40% | 31 (72%) | 4 (29%) |

| Unclear: Not reported | 4 (9%) | 4 (29%) |

| 2. Retention/Withdrawal | ||

| No: Retention <70%; Withdrawal > 30% | 2 (5%) | 1 (7%) |

| Yes: Retention ≥70%; Withdrawal ≤ 30% | 32 (74%) | 9 (64%) |

| Unclear: Not reported | 9 (21%) | 4 (29%) |

| 3. Attendance | ||

| No: <70% | 7 (16%) | 2 (14%) |

| Yes: ≥70% | 18 (42%) | 6 (43%) |

| Unclear: Not reported | 18 (42%) | 6 (43%) |

Includes 2 person‐focused trials for partners both rated acceptable on recruitment, retention, and attendance.

3.5. Intervention effects

Three trials reported couple‐focused interventions that, compared with usual care, increased partner distress about sexual function,24 worsened partner challenge appraisal,25 and reduced relationship satisfaction and intimacy for partners who had high levels of these constructs at baseline26 (Appendix D). By contrast, for patients, all intervention effects indicated improvement. Four trials included outcomes of interest27, 28, 29, 30 but did not report comparative results and were excluded. The remaining 29 trials (21 person‐focused: 20 patients, 1 partner and patient; 8 couple‐focused) showed a benefit for psychosocial or psychosexual outcomes (Table 2). Most (80%) person‐focused interventions were for men with localised disease. Of the effective interventions, most (95% person‐focused, 86% couple‐focused) significantly impacted patient outcomes. No person‐focused trials had a significant effect on relationship outcomes. No couple‐focused trials improved decision‐making outcomes or fatigue. No trials had a significant effect on partner QoL or sexuality outcomes regardless of intervention focus. Table 3 reports intervention components.

Table 2.

Person ‐ (N = 21) and couple ‐ (N = 8) focused trials that significantly (or moderate‐large effect size) and positively impacted psychosocial or psychosexual outcomes

| Study | N | Intervention(s) that had an effect | Comparison | Components | Deliverer | Follow‐up | Outcomes impacted | Sig level or effect size * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person‐focused interventions | ||||||||

|

Badger 2011,2013 Patients + partners |

71 | 1. Interpersonal psychotherapy + cancer education: patient and partner | 2. Health education attention: patient and partner |

1. E, SC, PS, C 2. E |

1. Nurse or social worker 2. Research assistants |

8 weeks post‐intervention |

Depression • Patient • Partner Negative affect • Patient Stress • Patient Fatigue • Patient • Partner Social well‐being • Partner Spiritual well‐being • Patient • Partner |

P < 0.001 P < 0.05 P < 0.001 P < 0.001 P < 0.01 P < 0.01 P < 0.01 P < 0.01 P < 0.01 |

|

8 (patients) or 4 (partners) individual telephone sessions over 8 weeks | ||||||||

|

Bailey 2004 |

39 |

Uncertainty management: cognitive reframing tailored to patient needs 5 weekly individual telephone sessions |

UC | E, CB, C, DS | Nurse | ~5 weeks post‐intervention | QoL | P = 0.01 |

|

Berry 2012,2013 |

494 |

Decision support 1 individual internet session |

UC | E, C, DS | Self‐admin | 6 months post‐intervention | Decisional uncertainty | P = 0.04 |

|

Campo 2014 |

40 |

Qigong 24 twice weekly group face‐to‐face sessions |

Stretch control | R | Qigong master and instructors | 1 week post‐intervention |

Fatigue Distress |

P = 0.02 P = 0.002 |

|

Carmack‐Taylor 2006,2007 |

134 |

1. 30 minutes expert speaker or facilitated discussion 2. 90 minutes expert speaker or facilitated discussion Both interventions 21 group face‐to‐face sessions over 6 months |

UC |

1. E, PS 2. E, PS |

Facilitator supervised by clinical psychologist | 6 months post‐intervention |

Anxiety Depression |

Sub‐group P = 0.02 Sub‐group P = 0.002 |

|

Chabrera 2015 |

142 |

Decision aid Individual printed |

UC | E, C, DS | Self‐admin | 3 months post‐baseline | Decisional conflict | P < 0.001 |

|

Chambers 2013 |

740 |

Telephone psycho‐educational 5 individual sessions: 2 pre‐tx, and 3 weeks, 7 weeks and 5 months post‐tx |

UC | E, CB, R, DS | Nurse Counsellor | 24 months post‐tx |

Cancer‐specific distress Mental health |

Sub‐group P < 0.008 Sub‐group P = 0.04 |

|

Diefenbach 2012 |

91 |

1. Prostate Interactive Educational System with or without tailoring to patient's information seeking style (combined results from arms)

1 individual internet/CD‐ROM session |

2. Control Read Standard National Cancer Institute booklets on PCa for 45 minutes 1 individual booklet |

1. E, DS 2. E |

Self‐admin | Immediately post‐intervention |

Confident about tx choice Prefer more information |

P = 0.02 P = 0.02 |

|

Hacking 2013 |

123 |

Decision navigation 1 individual face‐to–face or telephone session, audiotape and written notes |

UC | DS | Research assistants | 6 months post‐consult |

Decisional self‐efficacy Decisional regret |

P = 0.009 P = 0.04 |

|

Lepore 2003; Helgeson 2006 |

250 |

1. Education + group discussion (with family member/friend) 2. Education Both 6 weekly face‐to‐face group sessions |

Standard medical care |

1. E, PS 2. E |

Multiple health professionals | 12 months post‐ intervention |

Mental health Depression Sexual bother |

Sub‐group P < 0.05 Sub‐group P < 0.05 P < 0.01 |

|

Mishel 2009 |

252 |

1. Decision navigation: Patient only 2. Decision navigation: Patient and support person Both information + telephone calls to review content, identify/formulate questions and practise skills delivered to patient and/or support person individually (not dyad) Both individual/couple booklet, DVD and 4 telephone calls over 7‐10 days |

Control |

1. E, SC, C, DS 2. E, SC, C, DS |

Nurse, Self‐admin | 3 months post‐baseline | Decisional regret | P = 0.01 |

|

Penedo 2006; Molton 2008 |

191 |

1. 10‐week group CB stress management techniques + relaxation training 10 weekly group face‐to‐face sessions |

2. Half‐day stress management seminar (same content) 1 group face‐to‐face session |

1. E, CB, R, SC, PS, C 2. E |

Therapist | 12‐13 weeks post‐baseline |

Cancer‐related QoL Sexual function |

P < 0.05 Sub‐group P < 0.05 |

|

Penedo 2007 |

93 |

1. 10‐week group CB stress management techniques + relaxation training 10 weekly group face‐to‐face sessions |

2. Half‐day stress management seminar (same content) 1 group face‐to‐face session |

1. E, CB, R, SC, PS, C 2. E |

Therapist | 12‐13 weeks post‐baseline | Cancer‐related QoL | P = 0.006 |

|

Petersson 2002 |

118 |

Group rehabilitation programme (only or + individual support) including psychosocial components + physical activity 8 group face‐to‐face sessions over 8 weeks + booster group session after 2 months + written information |

No group intervention | E, CB, R | Multiple health professionals | 3 months post‐intervention start | Cancer‐related distress (Avoidance) |

Sub‐group P < 0.01 |

|

Schofield 2016 |

331 |

Nurse‐led group psycho‐educational consultation 4 x group face‐to‐face sessions (beginning, mid, completion, and 6 weeks post‐radiotherapy) + 1 individual session after 1st group consultation |

UC | E, PS, C | Uro‐oncology nurse | 6 months post‐tx | Depression | P = 0.0009 |

|

Siddons 2013 |

60 |

CB group intervention 8 group face‐to‐face sessions over 8 weeks |

Wait‐list | E, CB, R, C | Psychologist |

8 weeks (end of intervention) |

Masculine self‐esteem Sexual confidence Sexual QoL Orgasm satisfaction |

P = 0.037 P = 0.001 P = 0.046 P = 0.047 |

|

Traeger 2013 |

257 |

1. 10‐week group CB stress management techniques + relaxation training 10 weekly group face‐to‐face sessions |

2. Half‐day stress management seminar (same content) 1 group face‐to‐face session |

1. E, CB, R, SC, PS, C 2. E |

Therapist | 12‐13 weeks post‐baseline | Emotional well‐being | P < 0.05 |

|

Weber 2004 |

30 |

Peer support 8 individual face‐to‐face sessions over 8 weeks |

UC | PS | Peer (>3 years PCa survivor) | 8 weeks post‐baseline | Sexual bother | P = 0.014 |

|

Weber 2007 a,b |

72 |

Peer support 8 individual face‐to‐face sessions over 8 weeks |

UC | PS | Peer (>3 years PCa survivor) | 8 weeks post‐baseline |

Depression Self‐efficacy |

P = 0.03 P = 0.005 |

|

Wootten 2015, 2016 |

142 |

1. Online psycho‐education + moderated peer online forum (PsychE + F) 6 individual sessions over 10 weeks |

2. Moderated peer online forum (F) Individually accessed over 10 weeks |

1. E, CB, PS, C 2. PS |

Self‐admin | 6 months post‐baseline |

Distress Decisional regret Sexual satisfaction |

P = 0.02 P = 0.046 Sig level NR, Difference 1.24 (95%CI 0.25‐2.22) |

|

Yanez 2015 |

74 |

1. CB stress management + relaxation/stress reduction techniques 10 weekly group online sessions |

2. Health promotion attention‐control 10 weekly group online sessions |

1. E, CB, R, PS, C 2. E |

Therapist | 6 months post‐baseline | Depression | Cohen's d 0.5 |

| Couple‐focused interventions | ||||||||

|

Campbell 2007 |

30 |

Partner assisted coping skills training 6 ~weekly dyadic telephone sessions |

UC | E, CB, R, C | Therapist | ~6 weeks post‐baseline |

Sexual bother •Patient Depression • Partner |

Cohen's d 0.5 0.5 |

|

Chambers 2015 |

189 |

1. Peer‐delivered telephone support 2. Nurse‐delivered telephone counselling 8 (recruited pre‐surgery) or 6 (recruited post‐surgery) dyadic telephone sessions: 2 pre‐surgery and/or 6 post‐surgery over 22 weeks |

UC |

1. E, CB, PS, C 2. E, CB, SC, C, DS |

PCa Nurse counsellor | 12 months post‐recruitment |

Use of ED tx Patient |

p < 0.01 |

|

Couper 2015 |

62 |

Cognitive‐existential couple therapy 6 weekly dyadic face‐to‐face sessions |

UC | CB, SC | Mental health professional | 9 months post‐baseline |

Relationship function Partner |

P = 0.009 |

|

Giesler 2005 Patient data only |

99 |

Post‐tx nursing support 6 monthly dyadic sessions; 2 face‐to‐face and 4 telephone sessions |

UC | E, C | Oncology nurse | 12 months post‐tx |

Sexual limitation Cancer worry |

P = 0.02 P = 0.03 |

|

Manne 2011 |

71 |

Intimacy‐Enhancing Therapy 5 dyadic face‐to‐face sessions over 8 weeks |

UC | E, CB, SC, C | Therapist | 8 weeks post‐ baseline |

Cancer concern • Patient Cancer‐related distress • Partner Relationship satisfaction • Partner Intimacy • Partner |

Sub‐group P = 0.02 Sub‐group P = 0.02 Sub‐group P = 0.0002 Sub‐group P = 0.001 |

|

Thornton 2004 |

80 patients, 65 partners |

Pre‐surgical communication enhancement 1 dyadic face‐to‐face session |

UC delivered by a nurse | SC, C | Trained counsellor | 1 year post‐surgery |

Stress Partner |

partial η2 = 0.12 |

|

Titta 2006 Patient data only |

57 |

Intracavernous injection‐focused sexual counselling for couples following patient training in PGE1‐intracavernous injections Six 3‐monthly dyadic face‐to‐face sessions |

Control (partner invited to follow‐up visits every 3 months) | E, SC, C | NR | 18 months post‐surgery |

Erectile function Sexual satisfaction Sexual desire |

P < 0.05 P < 0.05 P < 0.05 |

|

Walker 2013 |

27 |

Educational intervention for couples to maintain intimacy 1 dyadic face‐to‐face session + booklet |

UC | E | Researcher familiar with ADT | 6 months post‐enrolment |

Intimacy •Patient Dyadic adjustment • Patient • Partner |

Cohen's d 0.6 1.0 0.5 |

Precision of effect and size of effect correspond to longest reported follow‐up; size of effect only reported if not significant. C, Communication; CB, Cognitive‐behavioural; DS, Decision Support; E, Education; ED, Erectile dysfunction; NS, Not significant; PCa, Prostate cancer; PS, Peer Support; QoL, Quality of Life; R, Relaxation; SC, Supportive Care; Tx, treatment; UC, Usual or standard care

Table 3.

Inclusion of specific components in effective in N = 34 person‐focused interventions and N = 9 couple‐focused interventions

| Components | Person‐focused interventions* | Couple‐focused interventions* |

|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | |

| Education | 85% (29) | 78% (7) |

| (psycho‐education, psycho‐sexual education, PCa education) | ||

| Communication | 44% (15) | 78% (7) |

| (partner, sexual, health professional, general or type not specified) | ||

| Peer support | 41% (14) | 11% (1) |

| (peer discussion, social support^) | ||

| Cognitive‐behavioural | 29% (10) | 56% (5) |

| (cognitive restructuring, behaviour change, cognitive‐behavioural stress management) | ||

| Decision support | 24% (8) | 11% (1) |

| (PCa treatment, sexual aids) | ||

| Relaxation | 24% (8) | 11% (1) |

| (meditation, relaxation techniques) | ||

| Supportive counselling | 12% (4) | 56% (5) |

| (counselling/psychotherapy, health professional discussion) |

Note that some trials had multiple arms and more than one effective intervention.

Social support may include general group discussion with peers.

NB. Total percentages may exceed 100% because of multiple intervention components.

PCa, prostate cancer.

3.5.1. Person‐focused

Decision making

Six trials improved patient decision‐making mostly for men diagnosed with early stage disease and/or recruited prior to treatment. Decision support, aid, or navigation reduced patient uncertainty,31, 32 conflict,33 and regret34, 35 about their treatment decision, and a combined online psycho‐educational intervention and moderated peer forum also reduced regret.36, 37 Patient self‐efficacy or confidence in their decision‐making was increased by decision navigation34 and interactive education interventions.38

Quality of life

An uncertainty management intervention improved QoL for patients on watchful waiting.39 In 2 trials, a 10‐week cognitive‐behavioural stress management intervention improved cancer‐specific QoL for patients with early stage disease.40, 41, 42

Fatigue

Participants who received Qigong43 or a health education intervention44, 45 experienced reduced fatigue.

Sexuality

Five trials reported better sexuality outcomes (80% of trials included majority of men who had radical prostatectomy). Combined education and group discussion,46, 47 and peer support,48 decreased sexual bother. A 10‐week group cognitive‐behavioural stress management intervention improved sexual function for men treated with prostatectomy (88% erectile dysfunction (ED)) who had high interpersonal sensitivity.40, 41 Sexual satisfaction improved for patients in a combined online psycho‐educational intervention and moderated peer support forum.7, 36 Only one trial improved multiple sexual outcomes; in addition to increased sexual QoL and orgasm satisfaction, Siddons et al49 reported increased masculine self‐esteem and sexual confidence for men treated with radical prostatectomy (90% ED) and who received a cognitive‐behavioural group intervention. Overall, 60% of trials reported follow‐up immediately following or close to intervention delivery.

Mental health

Eleven trials improved patient mental health outcomes. Patients receiving a combined online psycho‐educational intervention and moderated peer forum had less distress.36, 37 Qigong also decreased distress43; and a nurse‐led psycho‐education intervention50 and peer support51, 52 reduced depression. In 2 trials, a 10‐week cognitive‐behavioural stress management intervention improved emotional well‐being53 and depression.23

Mental health and cancer‐specific distress improved in younger, more highly educated patients who received a tele‐based psycho‐educational intervention.54 A multi‐modal intervention including cognitive‐behavioural therapy also reduced cancer‐related distress (avoidance) in patients with a monitor (cognitive scanning) coping style.55 Patients with high‐baseline depression or anxiety showed improvement in these constructs if they were allocated to either a multi‐modal intervention including either 30 or 90 minutes of an expert speaker/facilitated discussion.56, 57 In another trial, patients with lower baseline depression were less depressed if they received a combined education and group discussion intervention.46, 47 In this same study, patients with lower self‐esteem at baseline had less depression and better mental health if they participated in either a combined education and group discussion or education only intervention.

One trial improved patient and partner mental health outcomes.44, 45 Patients in the health education attention intervention had less depression, negative affect, stress, and greater spiritual well‐being. Effects on stress were more pronounced for men who were less educated, and greater reductions in depression were experienced if men were older, had lower PCa‐specific QoL, active chemotherapy, less social support or cancer knowledge. Patients receiving combined psychotherapy and education had more positive affect if they were more highly educated, had higher PCa‐specific QoL, or more social support. Partners in the health education intervention had improved depression, social, and spiritual well‐being.44, 45

3.5.2. Couple‐focused

Quality of life

Intimacy‐enhancing therapy increased cancer‐specific QoL for patients with early stage disease and higher symptom‐related concerns at baseline.26

Sexuality

Four trials improved sexuality outcomes for patients only. Coping skills training reduced sexual bother,58 and intracavernous injection‐focused sexual counselling increased patient sexual function, sexual satisfaction, and desire.59 Post‐treatment nursing support lessened the extent to which sexual dysfunction interfered with spousal role activities.60 Prostate cancer nurse‐delivered and peer‐delivered telephone counselling interventions uniquely reported increased use of ED treatment at 12‐month post‐recruitment follow‐up for men with localised disease who had prostatectomy.61

Mental health

Mental health was improved in 5 trials, predominantly for partners. Coping skills training reduced partner's depressed mood.58 Pre‐surgical communication enhancement intervention reduced partner stress.62 Cancer‐related distress lessened in younger women receiving cognitive‐existential couple therapy,63 and partners with high levels of baseline distress receiving intimacy enhancing therapy.26 Cancer‐related worry also reduced for patients receiving post‐treatment nursing support.60

Relationships

Three trials improved relationship outcomes, mostly for partners. Cognitive‐existential couple therapy enhanced relationship function for female spouses.63 Intimacy enhancing therapy was associated with improved partner relationship satisfaction and intimacy for partners with lower baseline scores on these variables.26 Education to maintain intimacy also improved intimacy for patients starting ADT, and dyadic adjustment for patients and their female partners.64

3.6. Intervention delivery

Effective person‐focused interventions were most commonly delivered in an individual (53%) or group (47%) setting; face‐to‐face (50%), via telephone (26%) or online (26%); by a psychologist/counsellor (41%), nurse (29%) or self‐administered (26%). Couple‐focused interventions were delivered to dyads most commonly face‐to‐face (67%) or by telephone (44%); by a psychologist/counsellor (44%) or nurse (22%).

4. DISCUSSION

Psychosocial and psychosexual intervention can improve decision‐related distress, mental health, domain‐specific, and health‐related QOL in men with PCa. Combinations of educational, cognitive behavioural, communication, and peer support have been most commonly applied and found effective; followed by decision support and relaxation; and to a much lesser extent supportive counselling. These components were often used in a multi‐modal approach, and delivered through both face‐to‐face and remote technologies, with therapist, nurse or peer support. In sum, multi‐modal psychosocial and psychosexual care for men with PCa, particularly localised disease, is both acceptable and effective.

The evidence is less clear for the female partners of these men and couples as a dyadic unit. Couple‐focused interventions were the least acceptable approach and almost half of the couple interventions produced poorer outcomes for partners. When couple interventions were effective, they improved relationship outcomes for the partner but not the man; had a positive effect on the partner's mental health but conversely; improved sexuality outcomes for the man but not the partner. No interventions improved sexuality outcomes for female partners. Based on these results, effective and acceptable interventions for female partners and couples remain an area of uncertainty. It may be that couples interventions have been primarily focused on the PCa survivor's needs, leaving the partner's concerns poorly managed. This is an area where significant further work is required to understand the needs and preferences of couples, and to determine approaches to improve sexual and relationship satisfaction for both partners.

Limitations of the research to date include small sample sizes; low statistical power; suboptimal statistical methods in some studies; inconsistency in measurement approaches; a lack of diversity in participants—particularly with regards to gay and bisexual men; men with advanced PCa; and men from socio‐economically deprived; and non‐Anglo‐Saxon backgrounds. Long‐term survivorship outcomes (>2 years) are yet to be addressed. In addition, intervention components were often described in a vague way such that it was not always clear what was actually delivered; and treatment fidelity and therapist adherence was in most studies not well described. Strengths of the current review by comparison with previous reviews include a departure from a narrow focus on specific intervention type(s), single outcomes, or sub‐groups; a consideration of acceptability as well as statistical significance; and examination of not only intervention effectiveness but also who benefits by considering the influences of socio‐demographic and medical characteristics of men and their partners; intervention format and delivery; and acceptability.

4.1. Clinical implications

Standards for psychosocial care with regards to screening for distress are now widely accepted,65 and the validity of the distress thermometer for men with PCa is well established with clear cut‐offs for caseness.11 In this review, approximately one‐quarter of interventions reported effects moderated by socio‐demographic or psychosocial variables; with age, educational level, domain‐specific QOL, baseline mental health, and social support important considerations in designing care. Hence, as well as taking into account levels of distress, it is also important to consider factors that both moderate intervention effectiveness and place men at risk of greater psychosocial distress and poorer QOL (such as age, domain‐specific QOL, socio‐economic deprivation) over the longer term.16 Survivorship care plans for PCa will need to be stepped according to the type and depth of need.66, 67 In conclusion, there is sufficient evidence to recommend multi‐modal psychosocial and psychosexual interventions for men with PCa; with distress screening and risk and need assessment built in to tailor support to the individual. As yet, there is insufficient evidence to confirm the optimal approach for female partners and couples.

We note that in this review education and communication support was commonly applied effectively across both person and couples‐focused interventions. By contrast, supportive counselling was often used for couples, whereas for patients peer support was more common. This may reflect in part what support methods are acceptable to men. Care approaches also need to consider the impact of PCa on men's masculine identities and embed sensitivity to these masculinities in psychosocial and psychosexual interventions in a way that extends beyond a reductionist focus on erectile dysfunction.65

4.2. Future research

There is a need for improvement in the field in study quality, especially with regard to treatment fidelity. Where interventions are multimodal better clarity about therapy components would assist application by clinicians. There remain gaps in knowledge about effective interventions for men with advanced cancer and how to best help couples and partners warrants further investigation. Finally, expanded research is needed targeting the needs of gay and bisexual men and those from non‐Anglo‐Saxon and socio‐economically deprived backgrounds.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Centre for Research Excellence in Prostate Cancer Survivorship (APP1116334).

APPENDIX A.

SEARCH STRATEGIES USED

For Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Embase, MEDLINE, PREMEDLINE and PsycINFO, and MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print databases (OVID):

| # | Searches |

|---|---|

| 1 | exp Prostatic Neoplasms/ |

| 2 | (prostat* adj3 (cancer* or carcinoma* or malig* or tumo?r* or neoplas* or metastas* or adeno*)).mp. |

| 3 | exp Neoplasms/ |

| 4 | exp Prostate/ |

| 5 | 3 and 4 |

| 6 | 1 or 2 or 5 |

| 7 | exp Affective Symptoms/ |

| 8 | exp affective disorders/ |

| 9 | affective disorders.mp. |

| 10 | exp Mood Disorders/ |

| 11 | mood*.mp. |

| 12 | exp Depression/ |

| 13 | depress*.mp. |

| 14 | exp Anxiety Disorders/ |

| 15 | exp Anxiety/ |

| 16 | anxiet*.mp. |

| 17 | anxious.mp. |

| 18 | exp Psychosomatic Medicine/ |

| 19 | exp Stress, Psychological/ |

| 20 | psycholog*.mp. |

| 21 | psychosoci*.mp. |

| 22 | (psycho adj soci*).mp. |

| 23 | (intrusive adj (thinking or thoughts)).mp. |

| 24 | intrusiveness.mp. |

| 25 | exp Mental Fatigue/ |

| 26 | exp “Conflict (Psychology)”/ |

| 27 | exp Emotions/ |

| 28 | emotion*.mp. |

| 29 | unhapp*.mp. |

| 30 | happiness*.mp. |

| 31 | sad.mp. |

| 32 | sadness.mp. |

| 33 | (anhedon* or melanchol* or fear* or worr*).mp. |

| 34 | (stress* or distress* or nervous* or nervos*).mp. |

| 35 | (uncertainty or hope or wellbeing).mp. |

| 36 | well being*.mp. |

| 37 | exp Adaptation, Psychological/ |

| 38 | exp Adjustment/ |

| 39 | (cognitive adj3 adjustment).mp. |

| 40 | exp Decision Making/ |

| 41 | decision making.mp. |

| 42 | decisional uncertainty.mp. |

| 43 | decisional regret.mp. |

| 44 | (decision* adj3 satisf*).mp. |

| 45 | exp Mental Health/ |

| 46 | Behavioral Symptoms/ |

| 47 | exp Attitude to Health/ |

| 48 | exp Patient Satisfaction/ |

| 49 | exp Personal Satisfaction/ |

| 50 | ((relationship or sexual) adj3 satisfaction).mp. |

| 51 | self efficacy.mp. |

| 52 | conflict*.mp. |

| 53 | (quality adj4 (life or living)).mp. |

| 54 | exp “Quality of Life”/ |

| 55 | quality of life.mp. |

| 56 | (QOL or HRQOL).mp. |

| 57 | exp Social Support/ |

| 58 | social support.mp. |

| 59 | Interpersonal Relations/ |

| 60 | exp interpersonal relationships/ |

| 61 | exp interpersonal interaction/ |

| 62 | social interaction.mp. |

| 63 | exp Personal Autonomy/ |

| 64 | autonomy.mp. |

| 65 | exp “independence (personality)”/ |

| 66 | exp Fatigue/ |

| 67 | (fatigue* or tiredness or libido* or impot*).mp. |

| 68 | exp Libido/ |

| 69 | sex drive.mp. |

| 70 | erectile dysfunction.mp. |

| 71 | exp Sexual Dysfunction, Physiological/ |

| 72 | exp Sexual Dysfunctions, Psychological/ |

| 73 | exp Sexual Function Disturbances/ |

| 74 | sexual dysfunction.mp. |

| 75 | exp Sexuality/ |

| 76 | sexuality.mp. |

| 77 | exp Self Concept/ |

| 78 | self image.mp. |

| 79 | (intimacy or wife or wives or dyad* or spous* or partner* or carer* or caregiv* or relational).mp. |

| 80 | exp marital relations/ |

| 81 | or/7‐80 |

| 82 | 6 and 81 |

| 83 | Randomized Controlled Trial.pt. |

| 84 | Pragmatic Clinical Trial.pt. |

| 85 | exp Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic/ |

| 86 | “Randomized Controlled Trial (topic)”/ |

| 87 | Randomized Controlled Trial/ |

| 88 | Randomization/ |

| 89 | Random Allocation/ |

| 90 | Double‐Blind Method/ |

| 91 | Double Blind Procedure/ |

| 92 | Double‐Blind Studies/ |

| 93 | Single‐Blind Method/ |

| 94 | Single Blind Procedure/ |

| 95 | Single‐Blind Studies/ |

| 96 | Placebos/ |

| 97 | Placebo/ |

| 98 | (random* or sham or placebo*).ti,ab,hw. |

| 99 | ((singl* or doubl*) adj (blind* or dumm* or mask*)).ti,ab,hw. |

| 100 | ((tripl* or trebl*) adj (blind* or dumm* or mask*)).ti,ab,hw. |

| 101 | 83 or 84 or 85 or 86 or 87 or 88 or 89 or 90 or 91 or 92 or 93 or 94 or 95 or 96 or 97 or 98 or 99 or 100 |

| 102 | 82 and 101 |

| 103 | limit 102 to English language |

| 104 | limit 103 to yr = “2000‐current” |

Used Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health filter for identifying randomised controlled trials (https://www.cadth.ca/resources/finding‐evidence accessed 17/02/2016)

For Health Technology Assessments (HTA) and Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) databases (Ovid):

| # | Searches |

|---|---|

| 1 | exp Prostatic Neoplasms/ |

| 2 | (prostat* adj3 (cancer* or carcinoma* or malig* or tumo?r* or neoplas* or metastas* or adeno*)).mp. |

| 3 | exp Neoplasms/ |

| 4 | exp Prostate/ |

| 5 | 3 and 4 |

| 6 | 1 or 2 or 5 |

| 7 | exp Affective Symptoms/ |

| 8 | exp affective disorders/ |

| 9 | affective disorders.mp. |

| 10 | exp Mood Disorders/ |

| 11 | mood*.mp. |

| 12 | exp Depression/ |

| 13 | depress*.mp. |

| 14 | exp Anxiety Disorders/ |

| 15 | exp Anxiety/ |

| 16 | anxiet*.mp. |

| 17 | anxious.mp. |

| 18 | exp Psychosomatic Medicine/ |

| 19 | exp Stress, Psychological/ |

| 20 | psycholog*.mp. |

| 21 | psychosoci*.mp. |

| 22 | (psycho adj soci*).mp. |

| 23 | (intrusive adj (thinking or thoughts)).mp. |

| 24 | intrusiveness.mp. |

| 25 | exp Mental Fatigue/ |

| 26 | exp “Conflict (Psychology)”/ |

| 27 | exp Emotions/ |

| 28 | emotion*.mp. |

| 29 | unhapp*.mp. |

| 30 | happiness*.mp. |

| 31 | sad.mp. |

| 32 | sadness.mp. |

| 33 | anhedon*.mp. |

| 34 | melanchol*.mp. |

| 35 | fear*.mp. |

| 36 | worry*.mp. |

| 37 | stress*.mp. |

| 38 | distress*.mp. |

| 39 | nervous*.mp. |

| 40 | nervos*.mp. |

| 41 | uncertainty.mp. |

| 42 | hope.mp. |

| 43 | wellbeing*.mp. |

| 44 | well being*.mp. |

| 45 | cope.mp. |

| 46 | coping.mp. |

| 47 | conflict.mp. |

| 48 | conflicts.mp. |

| 49 | exp Adaptation, Psychological/ |

| 50 | exp Adjustment/ |

| 51 | (cognitive adj3 adjustment).mp. |

| 52 | exp Decision Making/ |

| 53 | decision making.mp. |

| 54 | decisional uncertainty.mp. |

| 55 | decisional regret.mp. |

| 56 | (decision* adj3 satisf*).mp. |

| 57 | exp Mental Health/ |

| 58 | Behavioral Symptoms/ |

| 59 | exp Attitude to Health/ |

| 60 | exp Patient Satisfaction/ |

| 61 | exp Personal Satisfaction/ |

| 62 | ((relationship or sexual) adj3 satisfaction).mp. |

| 63 | self efficacy.mp. |

| 64 | (quality adj4 (life or living)).mp. |

| 65 | exp “Quality of Life”/ |

| 66 | quality of life.mp. |

| 67 | QOL.mp. |

| 68 | HRQOL.mp. |

| 69 | exp Social Support/ |

| 70 | social support.mp. |

| 71 | Interpersonal Relations/ |

| 72 | exp interpersonal relationships/ |

| 73 | exp interpersonal interaction/ |

| 74 | social interaction.mp. |

| 75 | exp Personal Autonomy/ |

| 76 | autonomy.mp. |

| 77 | exp “independence (personality)”/ |

| 78 | exp Fatigue/ |

| 79 | fatigue.mp. |

| 80 | tiredness.mp. |

| 81 | exp Libido/ |

| 82 | libido.mp. |

| 83 | sex drive.mp. |

| 84 | erectile dysfunction.mp. |

| 85 | impotence.mp. |

| 86 | exp Sexual Dysfunction, Physiological/ |

| 87 | exp Sexual Dysfunctions, Psychological/ |

| 88 | exp Sexual Function Disturbances/ |

| 89 | sexual dysfunction.mp. |

| 90 | exp Sexuality/ |

| 91 | sexuality.mp. |

| 92 | exp Self Concept/ |

| 93 | self image.mp. |

| 94 | relational*.mp. |

| 95 | intimacy*.mp. |

| 96 | wife.mp. |

| 97 | wives.mp. |

| 98 | dyad*.mp. |

| 99 | spous*.mp. |

| 100 | partner*.mp. |

| 101 | exp marital relations/ |

| 102 | carer*.mp. |

| 103 | caregiv*.mp. |

| 104 | or/7‐103 |

| 105 | 6 and 104 |

For Allied and Complementary Medicine (AMED) database (OVID):

| # | Searches |

|---|---|

| 1 | prostatic neoplasms/ |

| 2 | (prostat$ adj5 (cancer$ or Neoplas$ or malignan$)).mp. |

| 3 | 1 or 2 |

| 4 | clinical trials/ or random allocation/ |

| 5 | random$.mp. |

| 6 | trial.mp. |

| 7 | 4 or 5 or 6 |

| 8 | 3 and 7 |

| 9 | limit 8 to (English and yr = “2000‐Current”) |

For CINAHL database (EBSCO):

| # | Searches |

|---|---|

| S17 | S3 AND S15 Published date: 2009‐2016; English language; Exclude MEDLINE records |

| S16 | S3 AND S15 |

| S15 | S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 |

| S14 | TX allocat* random* |

| S13 | (MH “Quantitative Studies”) |

| S12 | (MH “Placebos”) |

| S11 | TX placebo* |

| S10 | TX random* allocat* |

| S9 | (MH “Random Assignment”) |

| S8 | TX randomi* control* trial* |

| S7 | TX ((singl* n1 blind*) or (singl* n1 mask*)) or TX ((doubl* n1 blind*) or (doubl* n1 mask*)) or TX ((tripl* n1 blind*) or (tripl* n1 mask*)) or TX ((trebl* n1 blind*) or (trebl* n1 mask*)) |

| S6 | TX clinic* n1 trial* |

| S5 | PT Clinical trial |

| S4 | (MH “Clinical Trials+”) |

| S3 | S1 OR S2 |

| S2 | TX (prostat* N3 (cancer* OR carcinoma* OR malignan* or tumo#r* OR neoplas* OR metast* OR adeno*)) |

| S1 | (MM “Prostatic Neoplasms”) |

Used SIGN filter for identifying randomised controlled trials (http://www.sign.ac.uk/methodology/filters.html#top accessed 17/02/2016)

APPENDIX B.

FRAMEWORK FOR CATEGORISING PSYCHOSOCIAL INTERVENTION COMPONENTS

Education

Psycho‐education: information or education about emotional impact of PCa and stress management; excludes cognitive‐behavioural approaches.

Psycho‐sexual education: information or education about sexuality or psycho‐sexual impact of PCa or treatment.

PCa education: information or education about PCa, treatment, and/or physical side effects.

Cognitive‐behavioural

Cognitive restructuring: working with cognitions, challenging negative thoughts, refocusing thoughts onto positives.

Behaviour change: Goal setting and problem solving or behavioural maintenance.

Cognitive behavioural stress management: intervention identified as CBSM.

Relaxation

Relaxation: meditation or relaxation techniques (eg, progressive muscle relaxation, Qigong, breathing exercises).

Supportive counselling

Counselling/psychotherapy (as identified by the study author): counselling or therapy offered as part of the intervention including sexual therapy, excludes cognitive‐behavioural approaches.

Health professional discussion: discussion with a health professional (excludes counselling/psychotherapy, routine/standard care).

Peer support

Peer support: shared experience with a peer who also has PCa (includes support groups, social support).

Social support: mentions social support generally and may also include informal peer support in a group setting, or does not specify type.

Communication

Partner: information or skill development to promote partners/couples communication (eg, treatment side‐effects, intimacy), excludes communication about sex.

Sexual: information or skill development to enable communication with partner about sex.

Health professional: information or skill development to encourage communication with health professional regarding treatment or post‐treatment concerns (eg, side‐effects).

Communication: general interpersonal communication or communication unspecified.

Decision support

PCa treatment: decision aid, tool or navigator to support PCa treatment decision.

Sexual aids: decision aid, tool or navigator to support decision to use erectile or other sexual aid or treatment.

APPENDIX C.

RISK OF BIAS ASSESSMENT OF TRIALS ADDRESSING QUESTION 1 (PATIENTS N = 56 TRIALS) AND QUESTION 2 (PARTNERS N = 14 TRIALS)

| Risk of bias category | Q1 N (%) | Q2 N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. What was the risk of bias from the random sequence generation? | ||

| Low: Adequate (eg, computer random number generator) | 20 (36) | 5 (36) |

| High: Inadequate | 2 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Unclear: Not reported | 34 (61) | 9 (64) |

| 2. What was the risk of bias from the allocation concealment? | ||

| Low: Adequately concealed (eg, central randomisation) | 16 (29) | 3 (21) |

| High: Inadequately concealed (eg, sealed envelopes) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Unclear: Concealment not reported or insufficient information to permit judgement | 40 (71) | 11 (79) |

| 3. What was the risk of bias from incomplete outcome dataa? | ||

| Low: Loss to follow‐up less than 50% and balanced across arms (<5% difference) | 19 (34) | 4 (29) |

| High: Loss to follow‐up greater than 50% or not balanced between arms or non ITT analyses | 24 (43) | 6 (43) |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | 13 (23) | 4 (29) |

| 4. What was the risk of bias from selective outcome reporting? | ||

| Low: Study protocol available and all pre‐specified outcomes reported | 7 (13) | 3 (21) |

| High: Study protocol available and not all pre‐specified outcomes reported | 14 (25) | 6 (43) |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement (eg, study protocol not found) | 35 (63) | 5 (36) |

| 5. What was the risk of bias from other sources**, a? | ||

| Low: Study appears free of other sources of bias | 39 (70) | 12 (86) |

| High: There is at least one important risk of bias from other sources | 14 (25) | 2 (14) |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to assess whether there is a risk of bias from other sources | 3 (5) | 0 (0) |

For primary outcome

Including differences in disease stage or follow‐up between arms, and analyses that did not consider baseline measures

ITT, intention‐to‐treat

APPENDIX D.

ELIGIBLE TRIALS INCLUDED IN THE REVIEW ADDRESSING QUESTION 1 (PATIENTS) AND QUESTION 2 (PARTNERS)

Table A1.

Trials comprising person‐focused interventions (N = 43: 41 patient only, 1 partner only, 1 patient and partner)

| Study | Participants # | Intervention | Intervention components | Comparator | Relevant outcomes | Precision of effect * | Size of effect * | Key findings | Acceptability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ames 2011 USA |

57 men with biochemical recurrence Median age 76 years |

Multi‐modal intervention which included psychosocial components Delivered by clinical psychologist, medical oncologist, dietician and physiatrist 8 group face‐to‐face sessions over 8 weeks Follow‐up 6 months post‐intervention |

E, CB, R, PS | Wait‐list control |

Mental health PCa‐related anxiety Stress Mood PCa‐related QoL |

NR NR NR NR NR |

−0.0 0.2 0.0 −0.1 0.1 |

The multi‐modal intervention did not significantly (or with a moderate or large effect size) improve outcomes |

100% retention at end of intervention 97% participants attended ≥6 of 8 intervention sessions 80% rated on a 5‐point scale helpfulness of intervention as 4 (very much) or 5 (extremely) |

|

Badger 2011, 2013 USA Patients + partners |

71 men and social network members (93% female; 83% partner, 13% family member, 4% friend) Men ≤6 months since tx Minimum 11% stage IV Patient M age 67 years; Partner M age 61 years |

1. Interpersonal psychotherapy + cancer education for patient and partner Delivered by nurse or social worker Patients: 8 individual telephone sessions over 8 weeks Partners: 4 individual telephone sessions over 8 weeks Follow‐up 8 weeks post‐intervention |

1. E, SC, PS, C 2. E |

2. Health education attention condition for patient and partner Delivered by research assistants Patients: 8 individual telephone sessions over 8 weeks Partners: 4 individual telephone sessions over 8 weeks |

Patients

Depression Positive affect Negative affect Stress Fatigue PCa‐related QoL Social well‐being Spiritual well‐being |

P < 0.001 NS P < 0.001 P < 0.001 P < 0.01 NS NS P < 0.01 |

NR NR NR NR NR NR NR NR |

The health education attention intervention significantly improved depression, negative affect, stress, fatigue, and spiritual well‐being when compared with psychotherapy + education intervention Men in the psychotherapy + education intervention had significantly greater improvement in positive affect if they were more highly educated, had higher PCa‐specific QoL or had more social support from friends Men in the health education intervention had significantly greater reduction in depression if they were older, had lower PCa‐specific QoL, were on active chemotherapy, had less social support or less cancer knowledge Men in the health education intervention had significantly greater reduction in stress if they were less educated |

40% recruitment rate 6% withdrew from psychotherapy + education intervention and 9% withdrew from education attention intervention 86% attendance in psychotherapy + education arm; 89% attendance in education attention intervention |

|

Partners

Depression Positive affect Negative affect Stress Fatigue Social well‐being Spiritual well‐being |

P < 0.05 NS NS NS P < 0.01 P < 0.01 P < 0.01 |

NR NR NR NR NR NR NR |

The health education attention intervention significantly improved depression, fatigue, social, and spiritual well‐being when compared with psychotherapy + education intervention | ||||||

|

Bailey 2004 USA |

39 men ≤10.3 years post‐tx decision on watchful waiting Stage T1‐3 (2% T3) M age 75 years |

Uncertainty management: cognitive reframing tailored to patient needs Delivered by a nurse 5 weekly individual telephone sessions Follow‐up ~5 weeks post‐intervention |

E, CB, C, DS | Usual care |

QoL (Cantrill's ladder) Mood |

P = 0.01 NS |

NR NR |

Uncertainty management intervention significantly improved QoL when compared with usual care |

76% recruitment rate 5% withdrew from intervention 95% follow‐up in both arms |

|

Beard 2011 USA |

54 men undergoing radiotherapy 91% ADT Stage M0 Median age 64 years |

Relaxation response therapy with cognitive restructuring (RRT) Delivered by psychologist 8 weekly individual face‐to‐face sessions during radiotherapy period Follow‐up 8‐12 weeks post‐intervention |

CB, R |

1. Wait‐list control 2. Reiki therapy |

Anxiety Depression Cancer‐related QoL Emotional well‐being subscale |

NS NS NS NS |

NR NR NR NR |

No significant improvements in outcomes were found when all 3 arms were compared |

73% recruitment rate 100% in Reiki and RRT arms completed study 89% in RRT arm attended all 8 sessions |

|

Berglund 2007 Sweden |

211 men ≤6 months since dx Stage 20% M1 M age 69 years |

1. Physical training + relaxation 2. Information sessions 3. Physical training + information sessions + relaxation Psychosocial components for all interventions delivered by physiotherapist (1, 3), nurse and urologist/oncologist (2, 3) All interventions comprised 7 group face‐to‐face sessions over 7 weeks Follow‐up 12 months |

1. R 2. E, PS 3. E, R, PS |

Standard care |

Anxiety Depression |

NS NS |

NR NR |

The multi‐modal interventions did not significantly improve outcomes |

50% recruitment rate 8% withdrew from physical training and physical training + information arms; 7% withdrew from information only arm—primarily because of transport issues |

|

Berry 2012, 2013 USA |

494 men recently dx and pre‐tx (50% had tx preference at baseline) Stage T1‐2 Median age 62‐63 years |

Decision support system Self‐administered 1 individual internet session Follow‐up 6 months post‐intervention |

E, C, DS + Clinic's usual educational resources (eg, pamphlets and links to reputable websites) |

Usual care |

Decisional uncertainty (100 unit scale) Decisional satisfaction Decisional regret Subgroup of men who made decision by 6 months Total decisional conflict (100 unit scale) |

P = 0.04 NS NS NS |

Coefficient −3.61 units NR NR −1.75 units |

Internet decision support significantly reduced decisional uncertainty when compared with usual care |

68% recruitment rate 100% compliance Authors identified good acceptability (M 25.1 on scale of 6‐30) |

|

Campo 2014 USA |

40 men <26 years since dx with significant fatigue and sedentary 48% ADT 61% Stage III‐IV Median age 72 years |

Qigong Delivered by qigong Master and his certified instructors 24 twice weekly group face‐to‐face sessions Follow‐up 1 week post‐intervention |

R |

Stretch control (24 twice weekly group face‐to‐face sessions) |

Fatigue (scale 0‐52) Distress |

P = 0.02 P = 0.002 |

Cohen's d NR ≥ 3‐point improvement in fatigue score for 69% qigong vs 38% controls −1.2 |

Qigong significantly improved fatigue and reduced distress when compared with stretch control however 47% had advanced disease in qigong arm compared with 82% in stretch control arm |

18% consented to eligibility assessment 20% withdrew from qigong arm; 35% withdrew from stretch control arm 85% median rate of attendance for qigong arm; 43% for stretch control |

|

Carmack‐Taylor 2006, 2007 USA |

134 men on ADT for next 12 months M age 69 years 12% depressed requiring clinical evaluation |

1. CB training to increase physical activity +30 minutes of expert speaker or facilitated discussion 2. 90 minutes of expert speaker or facilitated discussion All interventions delivered by a group facilitator who was supervised by a licenced clinical psychologist All interventions comprised 21 group face‐to‐face sessions over 6 months Follow‐up 6 months post‐intervention |

1. E, PS 2. E, PS |

Standard care |

Mental health Anxiety Depression Self‐esteem |

NS NS NS NS |

NR NR NR NR |

For the outcomes of depression and anxiety, there were significant group x baseline level interactions indicating that men with high rather than low baseline levels of depression (P = 0.02) or anxiety (P = 0.002) were more likely to benefit from either of the 2 interventions |

64% recruitment rate 4% 90 minutes E + PS and 3% controls withdrew 70% mean attendance rate for 90 minutes E + PS; ~82% attended at least 50% of sessions |

|

Chabrera 2015 Spain |

142 men with localised disease pre‐tx M age 69 years |

Decision aid Self‐administered Individual printed Follow‐up 3 months post‐baseline |

E, C, DS | Usual care | Decisional conflict | P < 0.001 |

Difference in change from baseline score −24.4 (100‐point scale) |

Decision aid significantly reduced decisional conflict when compared with usual care |

100% recruitment of eligible men 84% intervention and 82% control had follow‐up |

|

Chambers 2013 Australia |

740 men with localised disease pre‐tx M age 63 years |

Telephone psycho‐educational intervention Delivered by nurse counsellors 5 individual telephone sessions: 2 pre‐tx, and at 3 weeks, 7 weeks and 5 months post‐tx Follow‐up 24 months post‐tx |

E, CB, R, DS | Usual care |

Cancer‐specific distress Decisional uncertainty PSA anxiety Mental health Well‐being Sexual bother |

NS NS NS NS NS NS |

NR NR NR NR NR NR |

For a subgroup of participants who were younger with higher education levels, the psycho‐educational intervention significantly improved mental health (P = 0.04) and cancer‐specific distress (P < 0.008) |

82% recruitment rate At 6 months post‐tx, 7% withdrawn in intervention arm; 5% withdrawn in control arm 100% median rate of intervention attendance |

|

Chambers 2017 Australia |

189 men with metastatic disease and/or castration‐resistant biochemical progression 99% had received ADT M age 71 years 40% significant baseline distress |

1. Mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy (MBCT) Delivered by health professionals with oncology experience and professional training in MBCT 8 weekly group teleconference sessions Follow‐up 9 months post‐baseline |

1. E, CB, R, PS 2. E |

2. Minimally enhanced usual care Self‐administered Individual CD and information |

Psychological distress Cancer‐specific distress PSA anxiety PCa‐specific QoL |

NS NS NS NS |

NR NR NR NR |

MBCT did not significantly improve outcomes compared with minimally enhanced usual care |

46% recruitment rate 14% withdrew from MBCT arm and 6% withdrew from minimally enhanced usual care arm 30% attended all 8 MBCT sessions 72% of 61 men who completed a satisfaction survey rated intervention as very to extremely helpful |

|

Daubenmier 2006; Frattaroli 2008 USA |

93 men on active surveillance Stage T1‐T2 M age 66 years |

Multi‐modal lifestyle intervention including 1 hour/day stress management practice Deliverer of intervention NR Introduced at 1‐week residential retreat Weekly group face‐to‐face sessions ongoing Follow‐up 24 months post‐baseline |

R, PS | Usual care |

Mental health Stress Sexual function |

NS NS NS |

NR NR NR |

The multi‐modal intervention did not significantly improve outcomes |

51% recruitment rate Mean self‐reported programme adherence 95% at 24 months 91% intervention and 86% control completed 12‐month post‐baseline assessments |

|

Davison 2007 Canada |

324 men recently dx and considering tx Stage T1‐T2 M age 62 years |

1. Individualised decision support Self‐administered 1 individual interactive computer session Follow‐up 4‐6 weeks post‐baseline (after decision made) |

1. E, DS 2. E |

2. Generic decision support Self‐administered 1 individual video session |

Decisional conflict | NS | NR | Individualised decision support intervention did not significantly improve decisional conflict when compared with generic decision support |

86% recruitment rate 100% compliance 91% individualised intervention and 90% generic intervention post‐intervention follow‐up Mean total rating of satisfaction with preparation in decision making was 2.80 for individualised arm and 2.67 for generic arm. The individualised intervention was rated higher in helping considering pros and cons and communicating opinions |

|

Diefenbach 2012 USA |

91 men 4‐6 weeks since dx who had not made a tx decision Stage T1‐T2 M age 62 years |

1. Prostate Interactive Educational System (PIES) with or without tailoring to patient's information seeking style (combined results from both PIES arms)

Self‐administered 1 individual internet/CD‐ROM session Follow‐up immediately post‐intervention |

1. E, DS 2. E |

2. Control Asked to read Standard National Cancer Institute booklets on PCa for 45 minutes Self‐administered 1 individual booklet |

Confident about tx choice Prefer more time to decide Prefer more information Feel informed |

P = 0.02 NS P = 0.02 NS |

NR NR NR NR |

The interactive education intervention improved confidence about tx choice and reduced preference for more information when compared with printed information (however, baseline levels of confidence about tx choice were not measured) |

75% recruitment rate 100% compliance 82% PIES with tailoring, 75% PIES without tailoring and 79% controls had post‐intervention follow‐up Mean rating of helpfulness in decision making was 4.29 for tailored PIES, 4.10 for non‐tailored arm and 1.79 for control, scored 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much) |

|

Dieperink 2013 Denmark |

161 men 4 weeks since radiotherapy Stage T1‐T3 (46% T3) M age 68‐69 years |

Individualised psychosocial (2 sessions) and physical therapy (2 sessions) counselling Psychosocial components delivered by radiation therapists 2 individual psychosocial face‐to‐face sessions over 12‐14 weeks Follow‐up 22 weeks post‐baseline |

SC | Usual care |

Mental health Sexual QoL |

NS NS |

NR NR |

The multi‐modal intervention did not significantly improve outcomes |

77% recruitment rate 3% withdrew from intervention; 2% withdrew from control 90% had 100% attendance rate |

|

Feldman‐Stewart 2012 Canada |

156 men with a new dx and making a tx decision Stage T1‐T2 60% ≥ 60 years |

1. Decision aid—Information + explicit values clarification exercises Self‐administered 1 individual computerised session Follow‐up 12‐18 months post‐decision |

1. E, DS 2. E |

2. Decision aid—Information only Self‐administered 1 individual computerised session |

Decision regret | NS | NR | Including values clarification exercises in a decision aid did not significantly improve decision regret when compared with a decision aid providing information only |

37% recruitment rate (refusal because of: knowing what tx preferred or not needing further resources/help) 100% intervention completion and immediate post‐intervention follow‐up |

|

Hack 2007 Canada |

425 men attending primary tx consultation with radiation oncologist Stage T1‐4 (15% T3‐4) M age 67 years |

Audiotape of tx consultation with radiation oncologist Individual audiotape Follow‐up 12 weeks post‐consultation |

E, DS | No audio‐tape of tx consultation |

PCa‐related QoL Mood |

NS NS |

NR NR |

An audiotape of radiotherapy tx consultation did not significantly improve outcomes |

96% recruitment rate 35% of those who received tape did not listen to it M 83.0 for patients who listened to the tape (0 extreme dislike‐100 extreme like); 47% rated it ≥75 |

|

Hacking 2013 UK |

123 men newly dx with localised or early stage disease considering tx options and referred to urologist M age 65‐67 years |

Decision navigation Delivered by research assistants 1 individual face‐to–face or phone session, audiotape and written notes Follow‐up 6 months post‐consultation |

DS | Usual care |

Decisional self‐efficacy Decisional conflict Decisional regret Anxiety Depression Mental adjustment to cancer: Fighting spirit Anxiety Fatalism |

P = 0.009 NS P = 0.04 NS NS NS NS NS |

NR NR NR NR NR NR NR NR |

Decision navigation significantly increased decisional self‐efficacy and reduced decision regret when compared with usual care |

43% recruitment rate 2% withdrew from intervention prior to medical consultation At 6 months, men in the intervention arm used the consultation plan M 3.3 times, the consultation summary M 3.1 times and listened to the audiotape M 2.4 times 92% of respondents rated the intervention as very helpful before the urologist consultation |

|

Huber 2013 Germany |

203 men attending pre‐prostatectomy consultation M age 63 – 64 years |

Multimedia‐supported pre‐operative education Delivered by physician 1 individual computer‐based session Follow‐up 6‐10 hours after pre‐operative education |

E |

Standard pre‐operative education Delivered by physician |

Anxiety Decisional confidence |

NS NS |

Difference −0.5 −0.3 |

The addition of multimedia‐support to standard pre‐operative education did not significantly improve outcomes |

96% recruitment rate 100% compliance Complete satisfaction with pre‐operative education reported by 69% intervention and 52% control (P = 0.016) |

|

Kim 2002 USA |

152 men undergoing radiotherapy Stage A‐C (21% stage C) M age 71 years |

Specific information about radiotherapy procedures and side effects Self‐administered Individual audiotapes of 2 information sessions Follow‐up at end of radiotherapy tx |

E |

General information about radiotherapy Self‐administered Individual audiotapes of 2 information sessions |

Negative affect Fatigue |

NS NS |

NR NR |

Providing specific information did not significantly improve outcomes when compared with providing general information | Cannot assess |

|

Lepore 2003; Helgeson 2006 USA |

250 men ≤1 month since tx started Stage T1‐3 (12.8% T3) M age 65‐66 years |

1. Education + group discussion (attended with a family member or friend) Education delivered by urologist, oncologist, dietician, oncology nurse and clinical psychologist Group discussion delivered by male clinical psychologist to patients and by female oncology nurse to female family members 6 weekly group face‐to‐face sessions 2. Education only Delivered by urologist, oncologist, dietician, oncology nurse and clinical psychologist 6 weekly face‐to‐face group sessions Follow‐up 12 months post‐ intervention |

1. E, PS 2. E |

Standard medical care |

Mental health Depression Sexual function Sexual bother |

NS NS NS P < 0.01 |

NR NR NR NR |

Education and group discussion intervention significantly reduced sexual bother when compared with standard care For depression, there was a significant group x self‐esteem interaction indicating that men with lower self‐esteem were more likely to benefit from either intervention and a significant group x baseline depression interaction indicating that men with lower baseline depression levels were likely to benefit from education + group discussion intervention (P < 0.05) For mental health, there was a significant group x self‐esteem interaction indicating that men with lower self‐esteem were more likely to benefit from either intervention (P < 0.05) |

85% consented to assessment for eligibility; 77% of those eligible agreed to participate 67% mean attendance rate in both intervention arms Helpfulness M 4.22 (scored 1 not at all to 5 very) |

|

Manne 2004 USA Partners only |

60 female partners of men dx with any stage of PCa (5% Stage IV) M age 60 years 18% clinically significant distress (MHI score > 1.5 SD > normative mean) 49% had IES score > 19, ie, high cancer‐related distress |

Psychosocial educational groups for wives/partners Delivered by radiation oncologist, nutritionist, clinical psychologists and social worker 6 weekly group face‐to‐face sessions Follow‐up 1 month post‐ intervention |

E, CB, R, C |

Standard psycho‐social care Support from a social worker and referral to a community mental health professional |

Distress Cancer related‐distress Relationship communication about cancer |

NS NS NS |

NR NR NR |

Psychosocial education groups did not significantly improve outcomes when compared with standard psychosocial care |

57% recruitment rate (refusal because of: distance from centre, time and health problems) 11% drop‐out from intervention and 9% from control 85% mean attendance rate for intervention |

|

McQuade 2016 USA |

66 men scheduled to undergo radiotherapy Stage I‐III (21% ≥ T3a) M age 65 years |

Qigong/Tai chi Delivered by trained qigong master 3 individual or group face‐to‐face sessions per week during radiotherapy (6‐8 weeks) Follow‐up 3 months post‐radiotherapy |

R |

1. Light exercise Delivered by exercise physiologist 3 individual or group face‐to‐face sessions per week during radiotherapy (6‐8 weeks) 2. Wait‐list control |

Fatigue | NS | NR | A qigong and tai chi programme during radiotherapy did not significantly improve fatigue when compared with a light exercise programme or usual care |

38% recruitment rate 81% intervention, 73% light exercise control and 92% wait‐list control had follow‐up at end of intervention |

|

Mishel 2002 USA Reported patient data only |

252 couples (% female partner unclear) Men ≤2 weeks since catheter removal following surgery or ≤3 weeks since radiotherapy start Stage T1‐3 (27% T3) Patient M age 64 years |

1. Uncertainty management—Patient only Delivered by nurse 8 weekly individual phone calls 2. Uncertainty management—Patient and support person Delivered by nurse 8 weekly individual (not dyad) phone calls Follow‐up 7 months post‐baseline |

1. E, CB, C 2. E, CB, C |

Usual care |

Illness appraisal/ uncertainty Symptom intensity Symptom number Sexual function Sexual satisfaction |

NS NS NS NS P = 0.02 |

NR NR NR NR NR |

For patients, sexual satisfaction was significantly different between arms over time however actual effects of uncertainty management intervention were unclear | 77% recruitment rate |

|

Mishel 2009 USA Reported patient data only |

252 couples (~80% married or partnered) Men 10‐14 days pre‐tx consultation Stage T1‐2b Patient M age 63 years |

1. Decision navigation—Patient only Information + telephone calls to review content, identify/ formulate questions and practise skills Phone calls delivered by nurse Individual self‐administered booklet, DVD and 4 phone calls over 7‐ 10 days 2. Decision navigation—Patient and primary support person Intervention as for patient only intervention delivered to both patient and their support person individually (not dyad) Phone calls delivered by nurse Individual/couple self‐administered booklet, DVD and 4 phone calls over 7‐10 days Follow‐up 3 months post‐baseline |

1. E, SC, C, DS 2. E, SC, C, DS |

Control Handout on staying healthy during tx |

Mood Well‐being Decisional regret |

NS NS P = 0.01 |

NR NR NR |

Patients in both decision navigation interventions had significantly lower decision regret scores than controls |

75% recruitment rate Helpfulness of information resources rated significantly (P < 0.05) higher for men in either tx group vs controls |

|

Osei 2013 USA |

40 men ≤5 years since dx M age 67 years |

1. Online support Us TOO International website Self‐administered 3 times per week individual internet sessions over 6 weeks Follow‐up 8 weeks post‐baseline |

1. E, PS 2. E |

2. Resource kit US TOO International pamphlets Self‐administered Individual booklet over 6 weeks |

Mental health Sexual QoL Life satisfaction (Well‐being) Relationship satisfaction Positive Negative |

NS NS NS NS NS |

NR NR NR NR NR |

Online support and information did not significantly improve outcomes when compared with printed information |

5% of patients who received invitation were interested and eligible 58% said online support community met all or most of their needs M satisfaction 3.01 (scale 1‐4) |

|

Parker 2009; Gilts 2013 USA |

159 men scheduled for prostatectomy Stage I‐III (12.6% stage III) M age 60‐61 years |

1. Pre‐surgical stress management sessions Delivered by clinical psychologist 4 individual face‐to‐face sessions (3 prior to surgery and 1 at 48 hours post‐surgery + printed materials + audiotape 2. Supportive attention Delivered by clinical psychologist 4 individual face‐to‐face sessions Follow‐up 12 months post‐surgery |

1. E, CB, R, SC, PS 2. SC |

No meetings with a clinical psychologist |

Mood Cancer‐related distress Mental health Sexual function Sexual bother Subgroup with all measures at baseline and 12 months Distress Marital relationship satisfaction |

NS NS NS NS NS NS NS |

NR NR NR NR NR NR NR |

Stress‐management and supportive care interventions did not significantly improve outcomes when compared with controls |

77% recruitment rate 58% stress management arm, 72% supportive attention arm and 69% controls had 6 weeks post‐surgery follow‐up |

|

Penedo 2006; Molton 2008 USA |

191 men <18 months since tx Stage T1‐T2 M age 65 years |

1. 10‐week group CB stress management techniques + relaxation training Co‐delivered by licenced clinical psychologist and/or master's level clinical psychology students 10 weekly group face‐to‐face sessions Follow‐up 12‐13 weeks post‐baseline |

1. E, CB, R, PS, C 2. E |

2. Half‐day seminar on stress management techniques Same content as 10‐week intervention Co‐delivered by licenced clinical psychologist and/or master's level clinical psychology students 1 group face‐to‐face session |

Cancer‐related QoL Follow‐up 12‐13 weeks post‐baseline Subgroup + additional participants 121 men who had undergone prostatectomy 88% significant ED M age 60 years Sexual function |

P < 0.05 P < 0.05 |

NR NR |