Abstract

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have emerged as potential key regulators of the inflammatory response, particularly by modulating the transcriptional control of inflammatory genes. lncRNAs may act as an enhancer or suppressor to inflammatory transcription, function as scaffold molecules through interactions with RNA-binding proteins in chromatin remodeling complexes, and modulate dynamic and epigenetic control of inflammatory transcription in a gene-specific and time-dependent fashion. Here, we will review recent literature regarding the role of lncRNAs in transcriptional control of inflammatory responses. Better understanding of lncRNA regulation of inflammation will provide novel targets for the development of new therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: chromatin remodeling; epigenetics; inflammation; long noncoding RNA (long ncRNA, lncRNA); NF-κB; toll-like receptor (TLR); transcription regulation

Introduction

Because of the potentially destructive nature of the inflammatory response, the expression of inflammation-related genes is finely regulated at multiple levels, including transcription, mRNA processing, translation, phosphorylation, and degradation. Transcription represents an essential, and often the most important, regulatory determinant of the inflammation process. Many signaling pathways and transcription factors are involved in the inflammatory response, including the transcription factor nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), 2 MAPK, and JAK/STAT pathways, together controlling a multitude of inflammatory response genes (1, 2). Upon activation, these pathways directly activate and induce the expression of a limited set of transcription factors that promote the transcription of inflammatory genes. Whereas the mechanisms of initial activation and subsequent nuclear translocation of associated transcription factors for these signaling pathways are well-characterized, how the transcription of inflammatory genes is finely controlled in the nucleus to ensure that each individual gene is transcribed at the “right” place at the “right” time remains elusive. Perhaps this can be best represented by the inflammatory transcription induced by NF-κB. The NF-κB signaling cascade can be activated by inflammatory signals, including LPS, TNF-α, IL-1β, and reactive oxygen species, among others; many Toll-like receptors (TLRs) also activate NF-κB (3–8). Prior to an activating signal, NF-κB dimers are sequestered in the cytoplasm and held inactive by association with IκB proteins (9). Activating stimuli cause IκB degradation (10, 11), and consequently, free NF-κB dimers translocate to the nucleus, bind to κB sites, and promote gene transcription (12). Common targets of NF-κB include inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, cytoprotective proteins, and proteins regulating cell differentiation, proliferation, and survival (13, 14). In addition to its initial cytoplasmic activation, both the recruitment of NF-κB to target genes in the nuclei and NF-κB-induced transcriptional events after recruitment are finely controlled events to ensure proper transactivation of NF-κB target genes (15). Indeed, several waves of gene transcription have been demonstrated in macrophages following LPS stimulation. Broadly, these waves are categorized as transcription of early inflammatory genes (e.g. Tnfa, Cxcl2, Ptgs2/Cox2, and Il1b) and late inflammatory genes (e.g. Ccl5, Saa3, Ifnb1, Il6, Il12b, Nos2/INOS, and Marco) (16–18). The underlying molecular mechanisms of this dynamic transcription are unclear, and the transcription of late inflammatory genes may require synthesis of additional molecules and chromatin remodeling triggered by NF-κB activation (18, 19).

Large-scale transcriptome studies have revealed that transcription of protein-coding genes is far outweighed by the production of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), including thousands of long ncRNAs (lncRNAs) (20, 21). Emerging evidence recognizes lncRNAs as key regulators of gene expression implicated in diverse cellular processes. Although lncRNAs have been identified in almost all immune cells, their function remains largely unknown (22, 23). However, recent studies demonstrate that lncRNAs can be induced in innate immune cells and may act as key regulators of the inflammatory response (22, 24–27). Increased understanding of how lncRNAs function in this manner may impact future therapies for inflammation-associated diseases. Here, we aim to concisely review the current body of knowledge regarding the role of lncRNAs in transcriptional control of the inflammatory response. For recent advances in general features of lncRNAs in immunity, readers are referred to more comprehensive reviews on the topic (28–32).

lncRNAs, models of transcriptional control and expression in response to inflammation

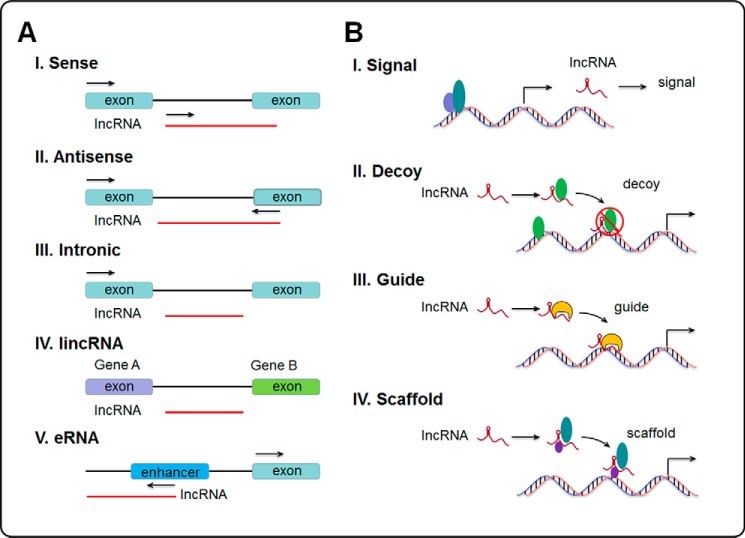

The definition of an lncRNA is a non-protein-coding transcript greater than 200 nucleotides in length, arbitrarily separating them from shorter classes of ncRNAs, such as the microRNAs. Multiple subclasses of lncRNAs have been proposed based upon their genomic locations (Fig. 1) (33–35). Long intergenic ncRNAs (lincRNAs) are located between protein-coding genes, whereas others are located and transcribed from introns of coding regions and are termed intronic lncRNAs, with reports suggesting that these form the largest class of lncRNAs (33). Sense lncRNAs are found on the sense strand of protein-coding genes, and may contain exons from these genes. Alternatively, antisense lncRNAs are located on the antisense strand and include natural antisense transcripts. Enhancer RNAs (eRNAs) are produced from the bidirectional transcription of enhancer regions (34). Although functionally different from mRNAs, the biogenesis of lncRNAs and mRNAs is remarkably similar. The majority of lncRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymerase II from genomic loci sharing similar chromatin states, are 5′-capped, spliced, and polyadenylated (22, 35).

Figure 1.

General classification of lncRNAs and their functional models in transcriptional control. A, classification of lncRNAs into five classes: exonic sense, intronic sense, antisense, bidirectional and intergenic, based upon their genomic locations and transcription (35). B, functional models of transcriptional control. lncRNAs may act as signals, decoys, guides or scaffolds to modulate gene expression at the transcriptional level (36).

lncRNAs are versatile molecules that can interact physically with DNA, other RNA, and protein, either through nucleotide base pairing or via formation of structural domains generated by RNA folding. These properties endow lncRNAs with a versatile range of capabilities to modulate gene transcription that are only beginning to be appreciated. Despite the great number of lncRNAs identified and the wide variety of effector proteins with which they are able to interact, four common mechanistic themes have been proposed (36). The first mechanistic theme that an lncRNA may exert its function through is by acting as a signal molecule. The specificity of lncRNA expression in specific cell and tissue types, along with their induction by many diverse stimuli, imply that lncRNAs can function as molecular signals in response to unique stimuli, serving as an indicator of transcriptional activity (37). Presumably acting to negatively regulate gene transcription, lncRNAs may function as decoys, the second mechanistic theme. These act as a decoy by binding their targets, without producing any further effect, as a mechanism of competitive regulation between lncRNAs and other molecules trying to exert an effect on the same molecular targets (38). Functionally opposite of the decoy, lncRNAs may act as guides, the next mechanistic theme. These lncRNAs bind their target effector proteins and serve to direct the ribonucleoprotein complex to sequence-specific sites, resulting in either positive or negative regulation of gene transcription (39). The final mechanistic theme is scaffolding, by which lncRNAs serve to bring multiple effector proteins or subunits of a complex together in a temporospatial fashion, coordinating their activities (40). These complexes can then mediate either transcriptional activation or repression or serve as guides, depending on the functional activities of the proteins involved (41, 42). In addition, new mechanisms are being discovered, such as eRNAs, which have been hypothesized to remain bound to enhancer regions, functioning to “tether” interacting proteins to the enhancer region (Fig. 1) (43). These mechanisms described above are not mutually exclusive, and many lncRNAs function by fulfilling more than one category (36).

Under normal circumstances, many lncRNAs are ubiquitously expressed across all human tissue types at a basal level and may be involved in maintaining cellular function (44). Similar to protein-coding inflammatory genes, many lncRNAs have been found to be targets of inflammatory pathways, and consequently, their expression profile is altered in various cell types during inflammation. Indeed, lncRNAs are differentially regulated in virus-infected cells (45) and in dendritic cells or macrophages following stimulation by ligands for TLR4 (LPS) and TLR2 (Pam3CSK4) (22, 26, 27). Through NF-κB signaling, lincRNA-Cox2, AS-IL1α, and PACER (p50-associated COX-2 extragenic RNA) are up-regulated in macrophages upon ligation of numerous TLRs, including TLR4 by LPS (26, 46, 47). Similarly, IL1β-eRNA, IL1β-RBT46, and lnc13 are induced in human monocytes and macrophages in response to LPS through NF-κB signaling (48, 49). NF-κB-interacting lncRNA (NKILA) is highly induced in response to IL-1β and TNF-α stimulation (50). Contrary to lncRNAs that are up-regulated in response to inflammation, lincRNA-EPS (erythroid prosurvival) is down-regulated upon TLR ligation through an NF-κB-dependent mechanism (51). Therefore, these lncRNAs may represent important members of an inducible inflammatory response. Whereas some inflammatory-responsive lncRNAs may only serve as molecular signals, it becomes clear that many others possess regulatory functions for controlling inflammatory gene expression, adding a new avenue for the transcriptional control of inflammatory responses.

lncRNAs as enhancers of the inflammatory response

Many lncRNAs can enhance the inflammatory response through a variety of means, commonly by increasing the transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines or other inflammatory target genes or by enhancing inflammatory signals, such as NF-κB signaling. THRIL (TNFα- and hnRNPL-related immunoregulatory lincRNA) is one of the many lncRNAs induced after TLR2 activation (52). Knockdown of THRIL suppresses the induction of TNF-α secretion, both after TLR2 activation and in unstimulated cells. Mechanistically, THRIL acts as a scaffold through interacting with heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein L (hnRNPL), and this complex binds to the TNF-α promoter to induce its transcription. Up-regulated after stimulation with LPS, IL-1β, or TNF-α, PACER has been shown to regulate the expression of a neighboring gene, PTGS2 (COX-2), a key inflammatory gene (46, 53, 54). PACER functions as a decoy by binding and sequestering NF-κB p50 homodimers, which lack transcription activation domains, away from the PTGS2 promoter. This sequestration promotes the formation and binding of NF-κB p50-p65 heterodimers to activate PTGS2 transcription. In response to Listeria monocytogenes infection and TLR1–4 activation, AS-IL-1α is highly up-regulated through NF-κB signaling (47). AS-IL-1α is required for the inducible expression of IL-1α. Knockdown of AS-IL-1α decreases acetylation of H3K9 and diminishes binding of RNA polymerase II to the transcription start site of IL-1α but not to control genes, indicating that AS-IL-1α specifically regulates the induction of IL-1α after TLR4 activation. Moreover, as they are transcribed from enhancer regions, several eRNAs, such as IL1β-eRNA and IL1β-RBT46, are found to be induced via NF-κB in response to TLR4 activation by LPS and are predominantly localized to the nucleus. Knockdown of IL1β-eRNA and IL1β-RBT46 together in activated cells specifically reduces the mRNA and protein levels of IL1-β and CXCL8, complying with their functional archetype as eRNAs (43, 48, 49).

lncRNAs as suppressors of the inflammatory response

Other lncRNAs have been identified to suppress or limit the extent of the inflammatory response. They achieve this effect by limiting the transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines or by interfering with inflammatory signal pathways, including NF-κB signaling. In this regard, lincRNA-EPS is down-regulated after TLR4 ligation with LPS, despite being highly expressed in resting macrophages (51, 55). lincRNA-EPS represses expression of immune response genes in resting macrophages, but after activation by microbial ligands such as LPS, this suppression is released, and gene transcription is induced. Accordingly, lincRNA-EPS deficient mice produce higher systemic levels of inflammatory cytokines in response to LPS challenge and are more prone to LPS-induced lethality (51). Mechanistically, lincRNA-EPS functions as a scaffold molecule and can interact with hnRNPL, which may partially explain how lincRNA-EPS is able to maintain a repressive chromatin state at the transcription start sites of many immune response genes. Another lncRNA implicated in suppression of the inflammatory response is Lethe. Knockdown of Lethe enhances the expression of several NF-κB target genes upon TNF-α stimulation (27). Lethe binds directly to the NF-κB p65 homodimer and acts as a decoy, preventing binding at the aforementioned target genes. Accordingly, overexpression of Lethe decreases p65 binding at NF-κB target genes such as Il6, Sod2, Il8, and Nfkbia upon TNF-α stimulation. Similar to Lethe, NKILA has been found to restrain NF-κB-driven inflammation. NKILA can mask the phosphorylation motifs of IκB to block IκB degradation, and thus it prevents the translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus, representing a class of lncRNAs that are able to regulate gene expression via post-translational modification of signaling proteins (49). Interestingly, lincRNA-p21 has been found to sequester p65 mRNA and thus attenuates the translation of p65, resulting in inhibition of basal and TNF-α-stimulated NF-κB activity, as measured by phospho-p65 (56). Taken together, it appears that induction of the above lncRNAs during inflammation provides negative regulatory feedback to inflammatory responses.

Curious case of lincRNA-Cox2

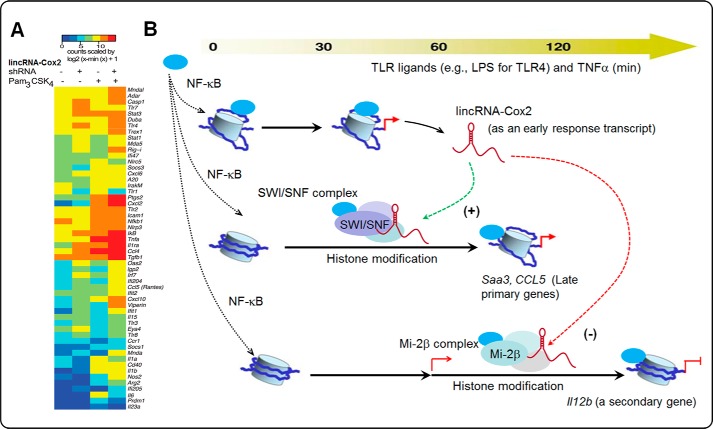

Arguably the best studied lncRNA that functions to modulate the inflammatory response is lincRNA-Cox2, which has been found to act as both an enhancer and a suppressor of inflammation in a gene-specific manner (18, 22, 26, 57). After TLR4 activation and ensuing NF-κB signaling, lincRNA-Cox2 was induced greater than 1000-fold in bone marrow-derived dendritic cells over the course of the following 12 h (22). Analysis of the expression time course revealed that it is an early primary NF-κB response gene, similar to Cxcl2 (18, 57). Functionally, silencing of lincRNA-Cox2 resulted in up-regulation of almost 800 genes and down-regulation of many other genes in non-stimulated cells (22, 57), suggesting a role for lincRNA-Cox2 in basal gene transcription. Many of these genes are inflammatory genes, including Ccl5, Cx3cl1, Ccrl, and IFN-stimulated genes, including Irf7, Oas1a, Oas1l, Oas2, Ifi204, and Isg15. Likewise, about 700 genes were found to be down-regulated, including Tlr1, Il6, and Il23α. Mechanistically, it appears that induction of lincRNA-Cox2 does not affect the NF-κB signaling cascades or RNA degradation machinery (57). Instead, lincRNA-Cox2 has been found to form a complex with heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) A/B and hnRNP-A2/B1, which together function to modulate the transcription of immune response genes (22, 26).

A more detailed analysis revealed that lincRNA-Cox2 knockdown causes a general down-regulation of the late primary responsive genes in LPS-stimulated macrophages (57). Different from the transcription of the late secondary responsive genes, transcription of the late primary genes does not require new protein synthesis (17, 18). Promoter recruitment of the ATP-dependent SWItch/Sucrose Non-Fermentable (SWI/SNF) complex has been demonstrated in the transcription of late primary response genes following NF-κB activation (26, 58). The SWI/SNF complex is a nucleosome remodeling complex composed of several proteins encoded by the SWI and SNF genes (e.g. SWIs, Brg1, or Brm) (58, 59). The SWI/SNF complex has DNA-stimulated ATPase activity and can destabilize histone-DNA interactions in reconstituted nucleosomes in an ATP-dependent manner (58, 60). After induction, lincRNA-Cox2 is assembled into the SWI/SNF complex through its interaction with the RNA-binding protein component (i.e. MyBBP1A, MYB-binding protein 1a) in both macrophages and microglia in response to LPS stimulation. This resulting lincRNA-Cox2–SWI/SNF complex can modulate SWI/SNF-associated chromatin remodeling and, consequently, transcription of late primary response genes in cells following LPS stimulation or microbial challenge (57). The involvement of an early response lincRNA in the transcription of late primary response genes may explain the “delayed but protein synthesis-independent” nature of these late primary genes. Complementarily, overexpression of lincRNA-Cox2 shifts the late primary genes, Saa3 and Ccl5, to become early response genes in murine macrophages in response to LPS stimulation (57).

Another study has shown that lincRNA-Cox2 is induced in intestinal epithelial cells in response to TNF-α and that its knockdown with siRNA significantly enhanced expression of Il12b (a late secondary responsive gene) in response to TNF-α compared with control siRNA after stimulation (61). Functionally, lincRNA-Cox2 promotes the recruitment of the Mi-2 nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase (Mi-2–NuRD) repressor complex to the promoter region of Il12b in intestinal epithelial cells in response to TNF-α stimulation. Recruitment of the Mi-2–NuRD complex facilitated by lincRNA-Cox2 suppresses the transcription of the Il12b gene through epigenetic histone modifications. Increased acetylation of H3K9 and H3K27 and decreased H3K27 methylation at the Il12b promoter region are found in intestinal epithelial cells following TNF-α stimulation. Knockdown of lincRNA-Cox2 attenuated the associated histone modifications in the Il12b promoter region induced by TNF-α (61).

This curious case of lincRNA-Cox2 indicates that lncRNAs can modulate inflammatory responses at every step of the regulatory network, including acting as an enhancer or suppressor to inflammatory transcription, functioning as scaffold molecules through their interactions with various RNA-binding proteins in chromatin remodeling complexes, and modulating dynamic and epigenetic control of gene transcription, in a gene-specific and time-dependent fashion (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Control of inflammatory response gene expression by lincRNA-Cox2. A, heat map representation of differentially regulated genes performed on RNA extracted from control or lincRNA-Cox2 shRNA knockdown mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages stimulated with Pam3CSK4 (a TLR2 ligand) for 5 h, based on the work of Carpenter et al. (30). B, lincRNA-Cox2 is an early NF-κB response gene. Upon induction, lincRNA-Cox2 is assembled into the SWI/SNF complex in macrophages in response to LPS stimulation. This resulting lincRNA-Cox2–SWI/SNF complex can modulate SWI/SNF-associated chromatin remodeling and, consequently, transcription of late primary response genes (e.g. Saa3 and Ccl5) in cells following LPS stimulation or microbial challenge (57). In addition, lincRNA-Cox2 can be assembled into the Mi-2–NuRD complex and subsequently recruited to the Il12b gene locus (a secondary response gene), resulting in trans-suppression through histone modification-mediated epigenetic mechanisms (61).

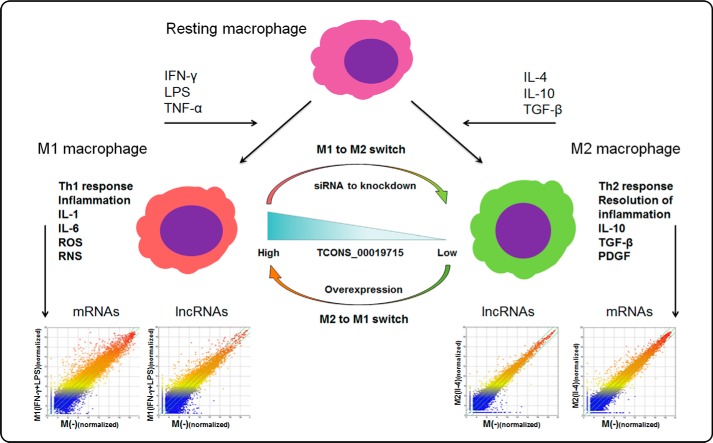

lncRNAs in macrophage M1/M2 switch

Another method by which lncRNAs may regulate the inflammatory process is by modulating the polarization state of macrophages. Upon activation, resting macrophages undergo phenotypic polarization based upon their microenvironment and transition into one of two functionally different states: the classically activated macrophage (M1) or an alternatively activated macrophage (M2). The M1 state is characterized by the production and release of pro-inflammatory mediators and is induced upon IFN-γ stimulation (62). Conversely, the M2 state is induced in response to IL-4 and has been proposed to be anti-inflammatory, serving as an immunomodulator by participating in the resolution of inflammatory responses (63, 64). The regulatory mechanisms controlling the expression of the constellation of genes in macrophages responding to activating conditions are not fully defined.

A recent report indicates that lncRNAs are partially responsible for the coordinated changes in gene expression occurring during macrophage polarization (65). A detailed genome-wide transcriptome analysis revealed a differentiated lncRNA expression profile in human monocyte-derived macrophages incubated in conditions causing activation toward M1 (IFN-γ + LPS) or M2 (IL-4) phenotypes. A total of 2252 intergenic lncRNAs were differentially expressed (fold change ≥2.0, p < 0.05) between the M2 (IL-4) group and M1 (IFN-γ + LPS) group. Among these lncRNAs, 1135 were up-regulated and 1117 were down-regulated (66). Interestingly, TCONS_00019715, an lncRNA located near the PAK1 gene, which encodes a protein important for macrophage polarization, is expressed at a higher level in M1 (IFN-γ + LPS) macrophages than in M2 (IL-4) macrophages. TCONS_00019715 expression was decreased when M1 (IFN-γ + LPS) converted to M2 (IL-4) and increased when M2 (IL-4) converted to M1 (IFN-γ + LPS). Knockdown of TCONS_00019715 following the activation of THP-1 human monocytic cells using IFN-γ and LPS diminished the expression of M1 (IFN-γ + LPS) markers and elevated the expression of M2 (IL-4) markers (66). Underlying mechanisms of the TCONS_00019715-mediated macrophage M1/M2 switch remain unclear. Therefore, a significantly altered lncRNA and mRNA expression profile occurs in macrophages exposed to different activating conditions. Dysregulation of some of these lncRNAs may play important roles in determining macrophage polarization (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

lncRNAs in M1 and M2 macrophage activation. Upon activation, resting macrophages can be activated into one of two functionally different states: the classically activated macrophage (M1, by IFN-γ, or LPS) or an alternatively activated macrophage (M2, by IL-4 or IL-10). Genome-wide analysis reveals differentiated lncRNA expression profiles of both mRNAs and lncRNAs in M1 (IFN-γ + LPS) and M2 (IL-4) macrophages (human monocyte-derived macrophages). Scatter plots show the variation in lncRNA and mRNA expression levels between the M1 (IFN-γ + LPS) and M2 (IL-4) and non-stimulated macrophages, based on the work of Huang et al. (66). TCONS_00019715 is expressed at a high level in M1 macrophages versus a lower level in M2 macrophages. Overexpression or knockdown of TCONS_00019715 causes reciprocal macrophage switch (66).

lncRNAs and pathogenesis of inflammatory disease

Because of the recently discovered functions of these many lncRNAs in the inflammatory response, it is not surprising that their dysregulation can lead to disease states. Although the underlying molecular mechanisms are still unclear, many lncRNAs have been implicated in the pathogenesis of various inflammatory diseases. THRIL has been found to be associated with Kawasaki disease, an inflammatory disease in children that can lead to coronary artery abnormalities and possible myocardial infarction (67). CXCL10, one of the genes found to be regulated by THRIL, is up-regulated in patients in the acute phase and has been identified as a possible biomarker of the disease (68). PACER is overexpressed in tissue samples from osteosarcoma when compared with control tissue and osteoblasts, and it enhances osteosarcoma cell proliferation and invasion (46). It is highly expressed in both knee and hip osteoarthritis chondrocytes when compared with non-osteoarthritic samples, suggesting a possible role in mediating inflammation-driven cartilage damage in osteoarthritis (54). Lethe is found to enhance the replication of the hepatitis C virus by suppressing interferon-stimulated gene expression after a type 1 interferon response (69). NKILA is found to serve as a tumor suppressor through a negative feedback loop of NF-κB and inhibits breast cancer progression and metastasis (50). lincRNA-p21 has been found to be a key negative regulator of NF-κB signaling in rheumatoid arthritis, and its decreased levels in disease may play a role in the inflammatory state seen in arthritic tissues (56). lnc13 has been implicated in celiac disease, a chronic, immune-mediated intestinal disorder that is triggered by ingested gluten (70). Levels of lnc13 are significantly down-regulated in samples from patients afflicted with celiac disease compared with control, suggesting that its down-regulation may be a contributing factor to the underlying inflammation in this disease (49).

Conclusions and perspectives

It has been found that a set of lncRNAs is induced in response to inflammation and that it plays a role in the regulation of gene transcription during the inflammatory response. This fine regulation is important for production of functional immune responses, and numerous studies have found that dysregulation of lncRNAs is associated with an array of human diseases. Thus far, we have learned that lncRNAs are able to enhance or suppress the inflammatory response in a gene-specific and time-specific fashion. They accomplish this fine regulation by acting as signals, decoys, guides, or scaffolds. As research in this area moves forward, continuing to uncover the mechanisms by which lncRNAs function, new mechanisms in addition to those summarized here will likely be found. Increasing our understanding of precisely how lncRNAs function in the regulation of inflammation will provide novel targets for the development of new therapeutic strategies for many inflammatory diseases.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants AI095532 and AI116323 and by the Creighton Cancer and Smoking Disease Research Program Award LB595 (to X.-M. C.). This is the first article in the Thematic Minireview Series: “Inflammatory transcription confronts homeostatic disruptions.” The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- NF-κB

- nuclear factor κB

- ncRNA

- non-coding RNA

- lncRNA

- long non-coding RNA

- lincRNA

- long intergenic ncRNA

- TLR

- Toll-like receptor

- hnRNPL

- heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein L

- eRNA

- enhancer RNA

- PACER

- p50-associated COX-2 extragenic RNA

- NKILA

- NF-κB-interacting lncRNA

- lincRNA-EPS

- lincRNA erythroid prosurvival

- THRIL

- TNFα- and hnRNPL-related immunoregulatory lincRNA

- hnRNP

- heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein

- SWI/SNF

- ATP-dependent SWItch/Sucrose NonFermentable

- Mi-2/NuRD

- Mi-2 nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase.

References

- 1. Pawate S., Shen Q., Fan F., and Bhat N. R. (2004) Redox regulation of glial inflammatory response to lipopolysaccharide and interferon γ. J. Neurosci. Res. 77, 540–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jung Y. J., Isaacs J. S., Lee S., Trepel J., and Neckers L. (2003) IL-1β-mediated up-regulation of HIF-1α via an NFκB/COX-2 pathway identifies HIF-1 as a critical link between inflammation and oncogenesis. FASEB J. 17, 2115–2117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adhikari A., Xu M., and Chen Z. J. (2007) Ubiquitin-mediated activation of TAK1 and IKK. Oncogene 26, 3214–3226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Qin H., Wilson C. A., Lee S. J., Zhao X., and Benveniste E. N. (2005) LPS induces CD40 gene expression through the activation of NF-κB and STAT-1α in macrophages and microglia. Blood 106, 3114–3122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fitzgerald D. C., Meade K. G., McEvoy A. N., Lillis L., Murphy E. P., MacHugh D. E., and Baird A. W. (2007) Tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) increases nuclear factor κB (NFκB) activity in and interleukin-8 (IL-8) release from bovine mammary epithelial cells. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 116, 59–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Renard P., Zachary M. D., Bougelet C., Mirault M. E., Haegeman G., Remacle J., and Raes M. (1997) Effects of antioxidant enzyme modulations on interleukin-1-induced nuclear factor κB activation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 53, 149–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chandel N. S., Trzyna W. C., McClintock D. S., and Schumacker P. T. (2000) Role of oxidants in NF-κB activation and TNF-α gene transcription induced by hypoxia and endotoxin. J. Immunol. 165, 1013–1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yamamoto M., Sato S., Mori K., Hoshino K., Takeuchi O., Takeda K., and Akira S. (2002) Cutting edge: a novel Toll/IL-1 receptor domain-containing adapter that preferentially activates the IFN-β promoter in the Toll-like receptor signaling. J. Immunol. 169, 6668–6672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baeuerle P. A., and Baltimore D. (1988) IκB: a specific inhibitor of the NF-κB transcription factor. Science 242, 540–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Beg A. A., Finco T. S., Nantermet P. V., and Baldwin A. S. Jr. (1993) Tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1 lead to phosphorylation and loss of IκBα: a mechanism for NF-κB activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 3301–3310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Henkel T., Machleidt T., Alkalay I., Krönke M., Ben-Neriah Y., and Baeuerle P. A. (1993) Rapid proteolysis of IκB-α is necessary for activation of transcription factor NF-κB. Nature 365, 182–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen F. E., Huang D. B., Chen Y. Q., and Ghosh G. (1998) Crystal structure of p50/p65 heterodimer of transcription factor NF-κB bound to DNA. Nature 391, 410–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lenardo M. J., and Baltimore D. (1989) NF-κB: a pleiotrophic mediator of inducible and tissue-specific gene control. Cell 58, 227–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pasparakis M., Luedde T., and Schmidt-Supprian M. (2006) Dissection of the NF-κB signaling cascade in transgenic and knockout mice. Cell Death Differ. 13, 861–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Natoli G., Saccani S., Bosisio D., and Marazzi I. (2005) Interactions of NF-κB with chromatin: the art of being at the right place at the right time. Nat. Immunol. 6, 439–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sen R., and Smale S. T. (2010) Selectivity of the NF-κB response. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a000257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bhatt D. M., Pandya-Jones A., Tong A. J., Barozzi I., Lissner M. M., Natoli G., Black D. L., and Smale S. T. (2012) Transcript dynamics of proinflammatory genes revealed by sequence analysis of subcellular RNA fractions. Cell 150, 279–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ramirez-Carrozzi V. R., Nazarian A. A., Li C. C., Gore S. L., Sridharan R., Imbalzano A. N., and Smale S. T. (2006) Selective and antagonistic functions of SWI/SNF and Mi-2b nucleosome remodeling complexes during an inflammatory response. Genes Dev. 20, 282–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Natoli G. (2009) Late-genes control of NF-κB-dependent transcriptional responses by chromatin organization. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 1, a000224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. ENCODE Project Consortium, Birney E., Stamatoyannopoulos J. A., Dutta A., Guigó R., Gingeras T. R., Margulies E. H., Weng Z., Snyder M., Dermitzakis E. T., Thurman R. E., Kuehn M. S., Taylor C. M., Neph S., Koch C. M., et al. (2007) Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature 447, 799–816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carninci P., Kasukawa T., Katayama S., Gough J., Frith M. C., Maeda N., Oyama R., Ravasi T., Lenhard B., Wells C., Kodzius R., Shimokawa K., Bajic V. B., Brenner S. E., Batalov S., et al. (2005) The transcriptional landscape of the mammalian genome. Science 309, 1559–1563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guttman M., Amit I., Garber M., French C., Lin M. F., Feldser D., Huarte M., Zuk O., Carey B. W., Cassady J. P., Cabili M. N., Jaenisch R., Mikkelsen T. S., Jacks T., Hacohen N., et al. (2009) Chromatin signature reveals over a thousand highly conserved large non-coding RNAs in mammals. Nature 458, 223–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Atianand M. K., and Fitzgerald K. A. (2014) Long non-coding RNAs and control of gene expression in the immune system. Trends Mol. Med. 20, 623–631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dempsey L. A. (2013) lncRNAs in immune cells. Nat. Immunol. 14, 1036 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Peng X., Gralinski L., Armour C. D., Ferris M. T., Thomas M. J., Proll S., Bradel-Tretheway B. G., Korth M. J., Castle J. C., Biery M. C., Bouzek H. K., Haynor D. R., Frieman M. B., Heise M., Raymond C. K., et al. (2010) Unique signatures of long noncoding RNA expression in response to virus infection and altered innate immune signaling. MBio. 1, e00206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Carpenter S., Aiello D., Atianand M. K., Ricci E. P., Gandhi P., Hall L. L., Byron M., Monks B., Henry-Bezy M., Lawrence J. B., O'Neill L. A., Moore M. J., Caffrey D. R., and Fitzgerald K. A. (2013) A long noncoding RNA mediates both activation and repression of immune response genes. Science 341, 789–792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rapicavoli N. A., Qu K., Zhang J., Mikhail M., Laberge R. M., and Chang H. Y. (2013) A mammalian pseudogene lncRNA at the interface of inflammation and anti-inflammatory therapeutics. Elife 2, e00762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Elling R., Chan J., and Fitzgerald K. A. (2016) Emerging role of long noncoding RNAs as regulators of innate immune cell development and inflammatory gene expression. Eur. J. Immunol. 46, 504–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Satpathy A. T., and Chang H. Y. (2015) Long noncoding RNA in hematopoiesis and immunity. Immunity 42, 792–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Carpenter S., and Fitzgerald K. A. (2015) Transcription of inflammatory genes: long noncoding RNA and beyond. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 35, 79–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Heward J. A., and Lindsay M. A. (2014) Long non-coding RNAs in the regulation of the immune response. Trends Immunol. 35, 408–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fitzgerald K. A., and Caffrey D. R. (2014) Long noncoding RNAs in innate and adaptive immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 26, 140–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. St Laurent G., Shtokalo D., Tackett M. R., Yang Z., Eremina T., Wahlestedt C., Urcuqui-Inchima S., Seilheimer B., McCaffrey T. A., and Kapranov P. (2012) Intronic RNAs constitute the major fraction of the non-coding RNA in mammalian cells. BMC Genomics 13, 504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kim T.-K., Hemberg M., Gray J. M., Costa A. M., Bear D. M., Wu J., Harmin D. A., Laptewicz M., Barbara-Haley K., Kuersten S., Markenscoff-Papadimitriou E., Kuhl D., Bito H., Worley P. F., Kreiman G., and Greenberg M. E. (2010) Widespread transcription at neuronal activity-regulated enhancers. Nature 465, 182–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Derrien T., Johnson R., Bussotti G., Tanzer A., Djebali S., Tilgner H., Guernec G., Martin D., Merkel A., Knowles D. G., Lagarde J., Veeravalli L., Ruan X., Ruan Y., Lassmann T., et al. (2012) The GENCODE v7 catalog of human long noncoding RNAs: analysis of their gene structure, evolution, and expression. Genome Res. 22, 1775–1789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang K. C., and Chang H. Y. (2011) Molecular mechanisms of long noncoding RNAs. Mol. Cell 43, 904–914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pandey R. R., Mondal T., Mohammad F., Enroth S., Redrup L., Komorowski J., Nagano T., Mancini-Dinardo D., and Kanduri C. (2008) Kcnq1ot1 antisense noncoding RNA mediates lineage-specific transcriptional silencing through chromatin-level regulation. Mol. Cell 32, 232–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kallen A. N., Zhou X. B., Xu J., Qiao C., Ma J., Yan L., Lu L., Liu C., Yi J. S., Zhang H., Min W., Bennett A. M., Gregory R. I., Ding Y., and Huang Y. (2013) The imprinted H19 lncRNA antagonizes let-7 microRNAs. Mol. Cell 52, 101–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Grote P., Wittler L., Hendrix D., Koch F., Währisch S., Beisaw A., Macura K., Bläss G., Kellis M., Werber M., and Herrmann B. G. (2013) The tissue-specific lncRNA Fendrr is an essential regulator of heart and body wall development in the mouse. Dev. Cell 24, 206–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yang L., Froberg J. E., and Lee J. T. (2014) Long noncoding RNAs: fresh perspectives into the RNA world. Trends Biochem. Sci. 39, 35–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Aguilo F., Zhou M. M., and Walsh M. J. (2011) Long noncoding RNA, polycomb, and the ghosts haunting INK4b-ARF-INK4a expression. Cancer Res. 71, 5365–5369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kotake Y., Nakagawa T., Kitagawa K., Suzuki S., Liu N., Kitagawa M., and Xiong Y. (2011) Long non-coding RNA ANRIL is required for the PRC2 recruitment to and silencing of p15(INK4B) tumor suppressor gene. Oncogene 30, 1956–1962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li X., Wu Z., Fu X., and Han W. (2014) lncRNAs: insights into their function and mechanics in underlying disorders. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 762, 1–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jiang C., Li Y., Zhao Z., Lu J., Chen H., Ding N., Wang G., Xu J., and Li X. (2016) Identifying and functionally characterizing tissue-specific and ubiquitously expressed human lncRNAs. Oncotarget 7, 7120–7133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhang Q., Chen C. Y., Yedavalli V. S., and Jeang K. T. (2013) NEAT1 long noncoding RNA and paraspeckle bodies modulate HIV-1 posttranscriptional expression. Mbio. 4, e00596–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Krawczyk M., and Emerson B. M. (2014) p50-associated COX-2 extragenic RNA (PACER) activates COX-2 gene expression by occluding repressive NF-κB complexes. eLife 3, e01776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chan J., Atianand M., Jiang Z., Carpenter S., Aiello D., Elling R., Fitzgerald K. A., and Caffrey D. R. (2015) A natural antisense transcript, AS-IL1α, controls inducible transcription of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1α. J. Immunol. 195, 1359–1363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. IIott N. E., Heward J. A., Roux B., Tsitsiou E., Fenwick P. S., Lenzi L., Goodhead I., Hertz-Fowler C., Heger A., Hall N., Donnelly L. E., Sims D., and Lindsay M. A. (2014) Long non-coding RNAs and enhancer RNAs regulate the lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response in human monocytes (published erratum appears in Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6814). Nat. Commun. 5, 3979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Castellanos-Rubio A., Fernandez-Jimenez N., Kratchmarov R., Luo X., Bhagat G., Green P. H., Schneider R., Kiledjian M., Bilbao J. R., and Ghosh S. (2016) A long noncoding RNA associated with susceptibility to celiac disease. Science 352, 91–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Liu B., Sun L., Liu Q., Gong C., Yao Y., Lv X., Lin L., Yao H., Su F., Li D., Zeng M., and Song E. (2015) A cytoplasmic NF-κB interacting long noncoding RNA blocks IκB phosphorylation and suppresses breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Cell 27, 370–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Atianand M. K., Hu W., Satpathy A. T., Shen Y., Ricci E. P., Alvarez-Dominguez J. R., Bhatta A., Schattgen S. A., McGowan J. D., Blin J., Braun J. E., Gandhi P., Moore M. J., Chang H. Y., Lodish H. F., Caffrey D. R., and Fitzgerald K. A. (2016) A long noncoding RNA lincRNA-EPS acts as a transcriptional brake to restrain inflammation. Cell 165, 1672–1685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Li Z., Chao T.-C., Chang K.-Y., Lin N., Patil V. S., Shimizu C., Head S. R., Burns J. C., and Rana T. M. (2014) The long noncoding RNA THRIL regulates TNFα expression through its interaction with hnRNPL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 1002–1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Smith W. L., DeWitt D. L., and Garavito R. M. (2000) Cyclooxygenases: structural, cellular, and molecular biology. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69, 145–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pearson M. J., Philp A. M., Heward J. A., Roux B. T., Walsh D. A., Davis E. T., Lindsay M. A., and Jones S. W. (2016) Long intergenic noncoding RNAs mediate the human chondrocyte inflammatory response and are differentially expressed in osteoarthritis cartilage. Arthritis Rheumatol. 68, 845–856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hu W., Yuan B., Flygare J., and Lodish H. F. (2011) Long noncoding RNA-mediated anti-apoptotic activity in murine erythroid terminal differentiation. Genes Dev. 25, 2573–2578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Spurlock C. F. 3rd., Tossberg J. T., Matlock B. K., Olsen N. J., and Aune T. M. (2014) Methotrexate inhibits NF-κB activity via lincRNA-p21 induction. Arthritis Rheumatol. 66, 2947–2957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hu G., Gong A. Y., Wang Y., Ma S., Chen X., Chen J., Su C. J., Shibata A., Strauss-Soukup J. K., Drescher K. M., and Chen X. M. (2016) LincRNA-Cox2 promotes late inflammatory gene transcription in macrophages through modulating SWI/SNF-mediated chromatin remodeling. J. Immunol. 196, 2799–2808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Euskirchen G. M., Auerbach R. K., Davidov E., Gianoulis T. A., Zhong G., Rozowsky J., Bhardwaj N., Gerstein M. B., and Snyder M. (2011) Diverse roles and interactions of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex revealed using global approaches. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Fan H. Y., Trotter K. W., Archer T. K., and Kingston R. E. (2005) Swapping function of two chromatin remodeling complexes. Mol. Cell 17, 805–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bouazoune K., Miranda T. B., Jones P. A., and Kingston R. E. (2009) Analysis of individual remodeled nucleosomes reveals decreased histone-DNA contacts created by hSWI/SNF. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 5279–5294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tong Q., Gong A. Y., Zhang X. T., Lin C., Ma S., Chen J., Hu G., and Chen X. M. (2016) LincRNA-Cox2 modulates TNF-α-induced transcription of Il12b gene in intestinal epithelial cells through regulation of Mi-2/NuRD-mediated epigenetic histone modifications. FASEB J. 30, 1187–1197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Nathan C. F., Murray H. W., Wiebe M. E., and Rubin B. Y. (1983) Identification of interferon-γ as the lymphokine that activates human macrophage oxidative metabolism and antimicrobial activity. J. Exp. Med. 158, 670–689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Jenkins S. J., Ruckerl D., Thomas G. D., Hewitson J. P., Duncan S., Brombacher F., Maizels R. M., Hume D. A., and Allen J. E. (2013) IL-4 directly signals tissue-resident macrophages to proliferate beyond homeostatic levels controlled by CSF-1. J. Exp. Med. 210, 2477–2491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Herbert D. R., Hölscher C., Mohrs M., Arendse B., Schwegmann A., Radwanska M., Leeto M., Kirsch R., Hall P., Mossmann H., Claussen B., Förster I., and Brombacher F. (2004) Alternative macrophage activation is essential for survival during schistosomiasis and down-modulates T helper 1 responses and immunopathology. Immunity 20, 623–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Recalcati S., Locati M., Marini A., Santambrogio P., Zaninotto F., De Pizzol M., Zammataro L., Girelli D., and Cairo G. (2010) Differential regulation of iron homeostasis during human macrophage polarized activation. Eur. J. Immunol. 40, 824–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Huang Z., Luo Q., Yao F., Qing C., Ye J., Deng Y., and Li J. (2016) Identification of differentially expressed long non-coding RNAs in polarized macrophages. Sci. Rep. 6, 19705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Shulman S. T. (1989) IVGG therapy in Kawasaki disease: mechanism(s) of action. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 53, S141–S146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ko T. M., Kuo H. C., Chang J. S., Chen S. P., Liu Y. M., Chen H. W., Tsai F. J., Lee Y. C., Chen C. H., Wu J. Y., and Chen Y. T. (2015) CXCL10/IP-10 is a biomarker and mediator for Kawasaki disease. Circ. Res. 116, 876–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Xiong Y., Yuan J., Zhang C., Zhu Y., Kuang X., Lan L., and Wang X. (2015) The STAT3-regulated long non-coding RNA Lethe promote the HCV replication. Biomed. Pharmacother. 72, 165–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Fernandez-Jimenez N., Castellanos-Rubio A., Plaza-Izurieta L., Irastorza I., Elcoroaristizabal X., Jauregi-Miguel A., Lopez-Euba T., Tutau C., de Pancorbo M. M., Vitoria J. C., and Bilbao J. R. (2014) Coregulation and modulation of NFκB-related genes in celiac disease: uncovered aspects of gut mucosal inflammation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23, 1298–1310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]