Abstract

The mechanisms whereby progesterone (P4), acting via the progesterone receptor (PR), inhibits proinflammatory/contractile gene expression during pregnancy are incompletely defined. Using immortalized human myometrial (hTERT-HM) cells stably expressing wild-type PR-A or PR-B (PRWT), we found that P4 significantly inhibited IL-1β induction of the NF-κB target genes, COX-2 and IL-8. P4–PRWT transrepression occurred at the level of transcription initiation and was mediated by decreased recruitment of NF-κB p65 and RNA polymerase II to COX-2 and IL-8 promoters. However, in cells stably expressing a PR-A or PR-B DNA-binding domain mutant (PRmDBD), P4-mediated transrepression was significantly reduced, suggesting a critical role of the PR DBD. ChIP analysis of hTERT-HM cells stably expressing PRWT or PRmDBD revealed that P4 treatment caused equivalent recruitment of PRWT and PRmDBD to COX-2 and IL-8 promoters, suggesting that PR inhibitory effects were not mediated by its direct DNA binding. Using immunoprecipitation, followed by MS, we identified a transcriptional repressor, GATA zinc finger domain–containing 2B (GATAD2B), that interacted strongly with PRWT but poorly with PRmDBD. P4 treatment of PRWT hTERT-HM cells caused enhanced recruitment of endogenous GATAD2B to COX-2 and IL-8 promoters. Further, siRNA knockdown of endogenous GATAD2B significantly reduced P4–PRWT transrepression of COX-2 and IL-8. Notably, GATAD2B expression was significantly decreased in pregnant mouse and human myometrium during labor. Our findings suggest that GATAD2B serves as an important mediator of P4–PR suppression of proinflammatory and contractile genes during pregnancy. Decreased GATAD2B expression near term may contribute to the decline in PR function, leading to labor.

Keywords: gene expression, inflammation, nuclear receptor, progesterone, transcription corepressor

Introduction

The actions of progesterone (P4) 3 are mediated by progesterone receptors (PRs), PR-A and PR-B, which are products of a single gene and ligand-activated members of the nuclear receptor family. Classically, binding of P4 to PR induces conformational changes in PR, followed by its dimerization and translocation from the cytoplasm into the nucleus, where it either directly binds to progesterone response elements in PR target gene promoters or tethers to other transcription factors bound to their respective response elements in the promoter regions of target genes to modulate their transcriptional activity. Transcription factors with which PR interacts include specificity protein 1 (Sp1) (1), nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) (2), and activator protein 1 (AP1) (3). After binding to progesterone response elements or tethering to other DNA-bound transcription factors, PRs recruit coactivator or corepressor complexes, which possess activities for histone modification and chromatin remodeling, leading to the induction or repression of target gene expression (4). In the pregnant uterus, P4 plays a critical role through its actions to maintain myometrial quiescence throughout most of gestation.

Both term and preterm labor are associated with an increased inflammatory response. This is characterized by elevated concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-1β and IL-6) in amniotic fluid (5) and infiltration of the myometrium, cervix, and fetal membranes by neutrophils and macrophages (6–8). The invading immune cells secrete proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (9), resulting in activation of NF-κB and other proinflammatory transcription factors in the myometrium (7, 10). Activated NF-κB, in turn, increases contraction-associated protein (CAP) gene expression (e.g. connexin 43 (CX43/GJA1) (7, 11) and oxytocin receptor (OXTR) (12)) as well as the expression of other inflammation-associated genes, such as prostaglandin F2α receptor (13) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2/PTGS2) (14, 15).

The mechanisms whereby P4–PR maintains uterine quiescence during pregnancy are diverse and probably include the direct antagonistic interaction of PR with proinflammatory transcription factors, such as NF-κB or AP-1 (15, 16), and other genomic actions, including increased expression of inhibitor of κBα (IκBα) and MAPK phosphatase 1 (MKP-1/DUSP1), which act to block activation of proinflammatory transcription factors (15, 17). We also observed that P4–PR blocks myometrial contractility by increasing expression of the gene encoding the transcriptional repressor, ZEB1, which binds to and suppresses expression of CX43 and OXTR (18).

The finding in rodents that circulating levels of maternal P4 decline precipitously near term (19) led to the concept that term labor is associated with P4 withdrawal. However, in humans and guinea pigs, circulating P4 levels remain elevated throughout pregnancy and into labor, as do myometrial levels of PR (20). Notably, even in mice, maternal P4 levels at term remain well above the Kd for binding to PR (21). These findings have led to the concept that parturition in all species is initiated by a concerted series of biochemical events that act to impair PR function and antagonize its ability to maintain myometrial quiescence. Some of the mechanisms postulated to contribute to the functional withdrawal of progesterone–PR prior to labor at term include a decrease in PR coregulators (22–25), increased expression of the inhibitory PR isoform, PR-C, an increase in the ratio of PR-A to PR-B (10, 26–28), and enhanced local metabolism of P4 to inactive products (29). However, the details of how these mechanisms are integrated to orchestrate the functional withdrawal of P4–PR during late gestation remain unknown.

To better understand the mechanism(s) responsible for the decline of PR function prior to labor at term, in the present study, we observed that the DNA-binding motif of PR plays an important role in P4-mediated inhibition of endogenous proinflammatory genes. We further observed that transrepressive activity of P4–PR occurred at the level of transcription initiation and was mediated by decreased recruitment of NF-κB p65 and RNA polymerase II (RNA Pol II) to the COX-2 and IL-8 promoter regions. Thus, we postulated that nuclear proteins interacting with the PR DNA-binding motif may play an important role in P4–PR–mediated transrepression. Using mass spectrometry to identify proteins that differentially interacted with PRWT versus the PRDBD mutants, we identified a transcriptional repressor, GATAD2B, which interacted with the PR DNA-binding motif and served an important role in P4–PR suppression of proinflammatory and CAP gene expression during pregnancy. We propose that during late gestation, a decrease in GATAD2B expression contributes to the decline in PR function and thereby contributes to the initiation of labor at term.

Results

Inhibitory effects of P4 on NF-κB–mediated reporter activity in HEK-293 cells is lost by mutagenesis of the PR DBD

To further define mechanisms underlying P4–PR–mediated anti-inflammatory responses, we first identified the functional domain(s) of PR important for these effects using transiently transfected HEK-293 cells. HEK-293 cells were used because they are easily transfectable and lack endogenous PR but contain cofactors required for transcriptional activity of transfected steroid receptors. Because sumoylation of nuclear receptors has been shown to play an important role in anti-inflammatory activity (30, 31), we used point mutagenesis to generate a PR-B K388R mutant in which the PR sumoylation site was disrupted (31–33). Previously, it was reported that the PR DBD contributed to P4–PR transrepressive activity on NF-κB p65-mediated transactivation in transfected cells; when the entire DBD was deleted, the P4–PR–mediated repressive activity was lost (2). To avoid causing major changes in PR structure, in the present study, we generated point mutations in two functional motifs within the DBD of PR. These included PR-B A604T, a point mutation in the D-box of the DBD, important for receptor dimerization, and PR-BmDBD, a triple mutation of the P-box, required for direct DNA binding (34). To test PR transrepression activity, an NF-κB–mediated reporter assay was used.

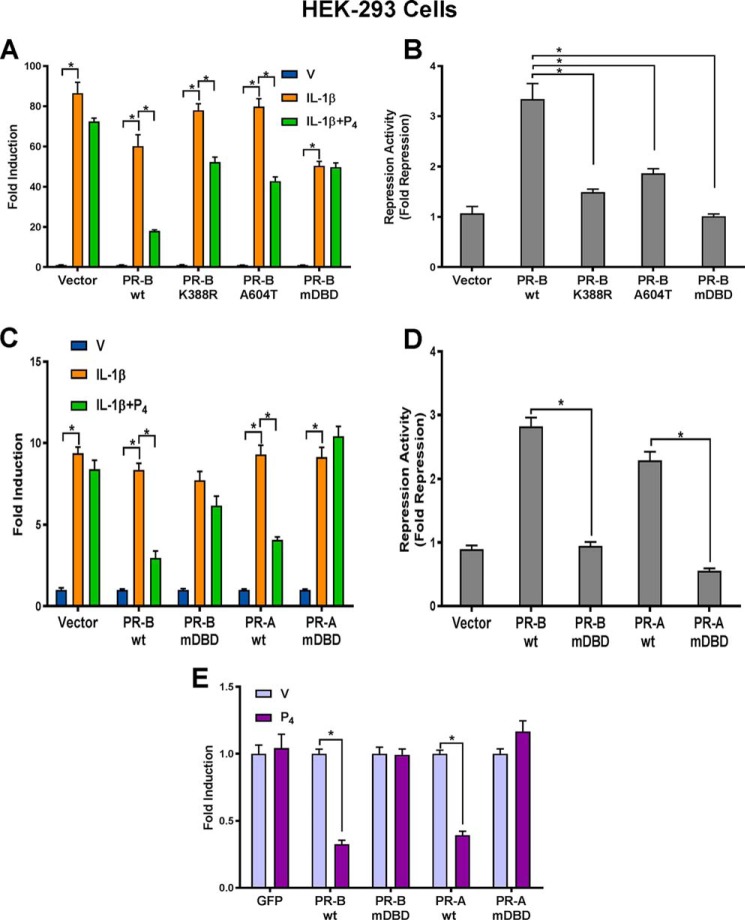

As shown in Fig. 1A, when HEK-293 cells were transiently transfected with a luciferase reporter plasmid containing five NF-κB consensus binding sites, treatment with IL-1β significantly induced luciferase activity compared with vehicle. Treatment with IL-1β + P4 did not affect luciferase activity because PR is not expressed in the HEK-293 cells. When cells were cotransfected with wild-type PR-B (PR-BWT) expression vector and reporter plasmids, treatment with P4 + IL-1β caused a significant decrease in luciferase activity compared with IL-1β alone. By contrast, in cells cotransfected with PR-BmDBD, P4-mediated repressive activity was completely lost. Whereas in cells cotransfected with expression vectors for PR-B mutants K388R or PR-B A604T, P4 repression of IL-1β-induced luciferase activity was still evident, the -fold repression was reduced significantly compared with the effects of PR-BWT (Fig. 1B). Taken together, these findings suggest that the sumoylation site, dimerization site, and DNA-binding motif of PR may play a role in P4 repression of NF-κB-mediated transcription. However, PR transrepression activity was most severely disrupted by mutation of the PR DNA-binding motif. To further study transrepressive efficacy of the PR-A isoform and effects of DBD mutations, HEK-293 cells were cotransfected with expression vectors encoding either PR-AWT, PR-BWT, or the corresponding DBD mutants. As can be seen in Fig. 1, C and D, when cells expressed PR-AWT or PR-BWT, co-treatment with P4 significantly inhibited IL-1β-induced luciferase activity to a similar extent. As observed for PR-BmDBD, mutation of the PR-A DBD (PR-AmDBD) completely blocked transrepression activity. To confirm that P4–PR–mediated repression of NF-κB activity was direct, rather than through an indirect mechanism, such as induction of IκBα (15, 43), a mammalian one-hybrid reporter assay was used. Using this assay, HEK-293 cells were cotransfected with Gal4–p65 CTD expression vector (35), encoding a chimeric protein comprised of the C-terminal transactivation domain (amino acids 286–551) of NF-κB p65 fused to the DBD of Gal4, a GAL4 luciferase reporter, and PRWT or PRmDBD expression vectors. The Gal4 DBD, containing a nuclear localization sequence, binds to Gal4-binding sites; luciferase activity is transactivated via the p65 transactivation domain. As shown in Fig. 1E, treatment with P4 significantly repressed luciferase activity compared with vehicle when cells were cotransfected either with PR-BWT or PR-AWT expression vectors. By contrast, cotransfection of PR-BmDBD or PR-AmDBD expression vectors failed to exert transrepressive activity. These data suggest that P4–PR directly repressed p65 transactivation and that the PR DNA-binding motif plays an important role in transrepression activity.

Figure 1.

Progesterone–PR–mediated repression of NF-κB reporter activity in HEK-293 cells is lost by mutagenesis of the PR DBD. A, HEK-293 cells were cotransfected with NF-κB-luciferase reporter constructs, Renilla luciferase plasmid, and expression vectors of PR-BWT and PR-B mutants, including PR-B K388R (sumoylation mutant), PR-B A604T (dimerization mutant), and PR-BmDBD P-box mutant. One day after transfection, cells were treated with DMSO (V), IL-1β (10 ng/ml), or IL-1β plus P4 (100 nm) for 6 h. B, repression activity/-fold repression of data shown in A was calculated by dividing the “-fold induction” for PR-BWT and each PR-B mutant in response to IL-1β by the -fold induction in response to IL-1β + P4. C, to further study the effects of DBD mutations on transrepression activity of PR-B and PR-A, HEK-293 cells were cotransfected with PR-BWT, PR-AWT, or the corresponding DBD mutants and with NF-κB-luciferase reporter constructs and Renilla luciferase plasmid. One day after transfection, cells were treated with DMSO (V), IL-1β (10 ng/ml), or IL-1β plus P4 (100 nm) for 6 h. D, repression activity of PR-BWT and PR-AWT and corresponding DBD mutants shown in C was calculated for cells transfected with each PR isoform and mutant by dividing the -fold induction in response to IL-1β by the -fold induction in response to IL-1β + P4. E, HEK-293 cells were cotransfected with Gal4–p65 C-terminal transactivation domain expression vector, GAL4 luciferase reporter, and PRWT or PRmDBD expression vector, as indicated. One day after transfection, cells were treated with DMSO (V) or P4 (100 nm) for 24 h. Cells from each experiment were then harvested, and firefly luciferase and Renilla luciferase activities were assayed. Relative luciferase activities were calculated by normalizing firefly luciferase activity to Renilla luciferase activity in the same samples to correct for transfection efficiencies. Data for experiments shown in A–E are the mean ± S.E. (error bars) of three replicate determinations for each treatment group. *, significant (p < 0.05) difference between samples.

PR DNA-binding motif mediates P4 repression of NF-κB-regulated gene expression in stably transfected human myometrial cells

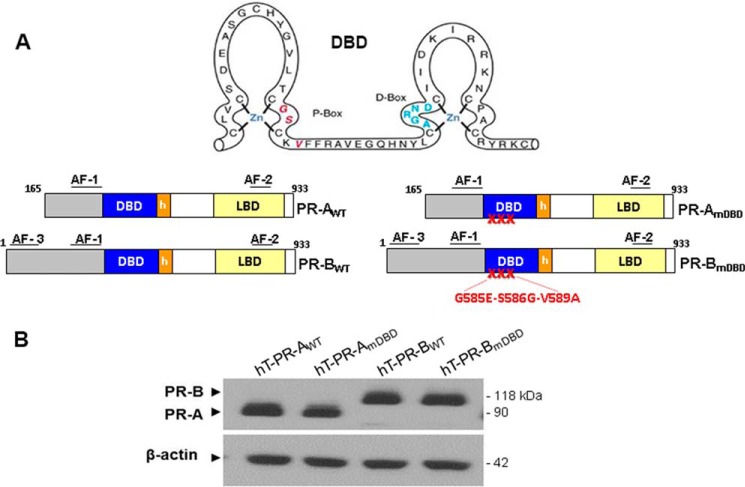

To evaluate the roles of PR-A and PR-B and their DNA-binding motifs in P4-mediated repression of endogenous proinflammatory and CAP gene expression, we utilized immortalized human myometrial cells (hTERT-HM) that lack endogenous PR to develop cell lines stably expressing either GFP alone or GFP-conjugated PR-BWT or PR-AWT or their corresponding DNA-binding domain mutants (PRmDBD) (Fig. 2A). These cells maintain characteristics of myometrial smooth muscle cells (36) and contract in response to a number of contractile stimuli (18, 37). As shown in the representative immunoblot (Fig. 2B), PR expression levels in the four genetically modified stable hTERT-HM cell lines were comparable.

Figure 2.

WT and mutant PR-A and PR-B isoforms are expressed at equivalent levels in stably transfected hTERT-HM cells. A, hTERT immortalized human myometrial cells were stably transformed using recombinant lentiviruses expressing PR-BWT, PR-BmDBD, PR-AWT, and PR-AmDBD conjugated to GFP at their N-terminal ends. PR-B DBD and PR-A DBD mutants (PRmDBD) contained a triple mutation (G584E/S585G/V589A) within the P-box region of the DBD. B, immunoblotting of total cell lysates revealed that levels of PR expression in the four stably transfected cell lines were equivalent. LBD, ligand-binding domain.

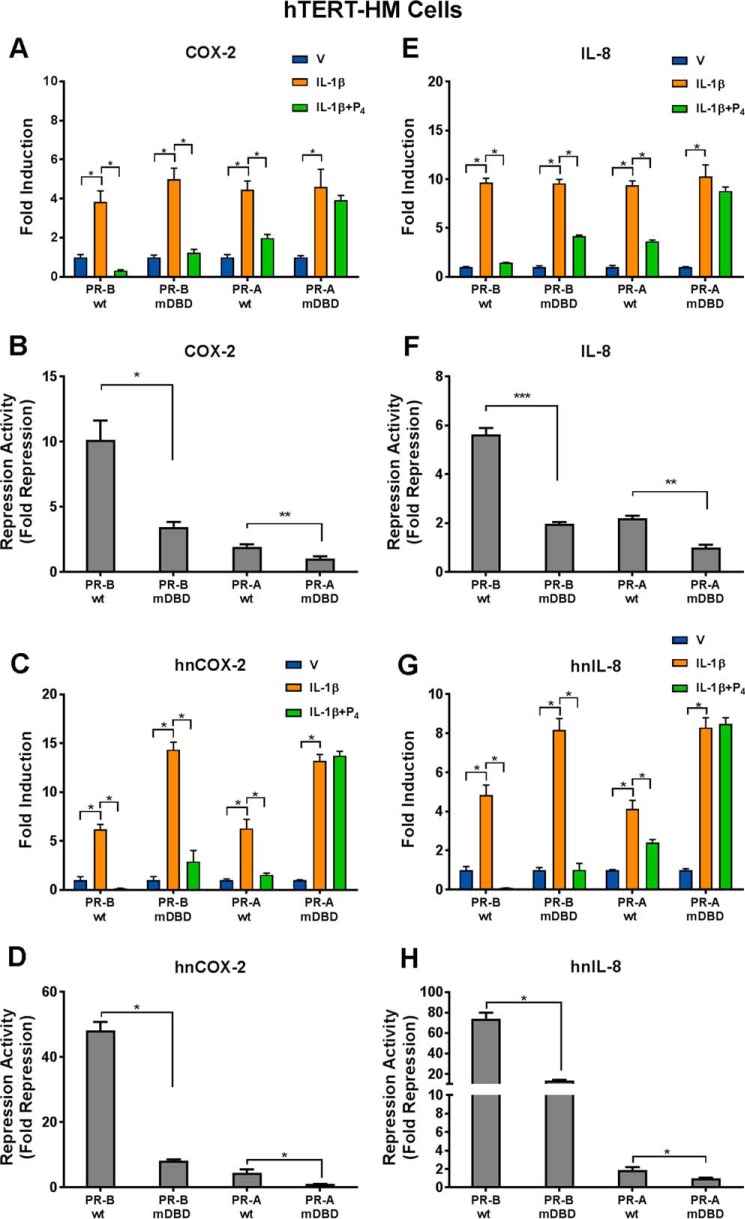

mRNA levels of proinflammatory and CAP genes in the cell lines cultured in the absence or presence of IL-1β with or without P4 for 2 h were analyzed by RT-qPCR. As shown in Fig. 3, in cells stably expressing either PR-BWT or PR-AWT, co-treatment with P4 significantly reduced IL-1β-induced COX-2 and IL-8 expression (Fig. 3, A and E), compared with IL-1β alone. Although both PR-BWT and PR-AWT had the capacity to repress COX-2 and IL-8 expression, the repressive activity mediated by PR-BWT was significantly greater than that of PR-AWT (Fig. 3, B and F). In cells stably expressing the PR-BmDBD mutant, P4-mediated repression activity was significantly reduced compared with cells expressing PR-BWT, whereas in cells expressing the PR-AmDBD mutant, P4 no longer could repress IL-1β–induced COX-2 and IL-8 mRNA expression (Fig. 3, B and F). Similar findings were obtained for endogenous mRNA expression of the proinflammatory genes, CCL-2 and IL-6 (data not shown).

Figure 3.

The PR DNA-binding motif plays an important role in P4-mediated transrepression of COX-2 and IL-8 promoter activity in human myometrial cells. hTERT-HM myometrial cells lines stably expressing either PR-BWT, PR-BmDBD, PR-AWT, or PR-AmDBD and cultured in the absence or presence of IL-1β with or without P4 were utilized. RT-qPCR was used to analyze expression of endogenous COX-2 (A–D) and IL-8 (E–H). A, B, E, and F, cells were treated with DMSO vehicle (V), IL-1β (10 ng/ml), or IL-1β + P4 (100 nm) for 2 h. Total RNA was extracted and reverse-transcribed, and the relative abundance of COX-2 (A) and IL-8 (E) mRNA transcripts was determined by qPCR. C, D, G, and H, to examine the effects of P4 on IL-1β induction of nascent COX-2 and IL-8 hnRNA expression, the uridine analog EU (200 μm) was added to the medium at the time that cells were placed in DMSO, IL-1β, or IL-1β + P4. After 40 min of treatment, total RNA was extracted, and the EU-labeled nascent RNA was isolated and reverse-transcribed. The relative abundance of nascent COX-2 (C) and IL-8 (G) mRNA transcripts was determined by qPCR. B, D, F, and H, -fold repression activity was calculated by comparing the levels of RNA expression in cells treated with IL-1β alone with the RNA levels after treatment with IL-1β plus P4. Data shown in A–H are the mean ± S.E. (error bars); significant (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001) difference between samples.

To determine whether the P4–PR–mediated transrepression activity occurred at the level of transcription initiation, the uridine analogue, 5-ethynyl uridine (EU), was used to label and isolate newly synthesized nascent RNA; levels of heterogeneous nuclear RNA (hnRNA) were analyzed by RT-qPCR. The hTERT-HM cells stably transfected with GFP conjugates of PR-AWT, PR-BWT, or the corresponding DBD mutants were cultured for only 40 min with or without IL-1β and with or without P4 to ensure that the level of hnRNA for a given gene was representative of transcriptional initiation. When cells were treated with IL-1β alone, COX-2 (Fig. 3C) and IL-8 (Fig. 3G) hnRNA levels were significantly increased compared with vehicle-treated cells. In both PR-BWT– and PR-AWT–expressing cells, co-treatment with P4 significantly reduced COX-2 and IL-8 hnRNA levels (Fig. 3, C and G) suggesting that P4–PR inhibition of IL-1β-induced expression is at the level of transcription initiation. In cells expressing PR-BmDBD, P4 retained its ability to repress transcription initiation, but transrepression activity was significantly reduced compared with cells expressing PRWT (Fig. 3, D and H). However, in PR-AmDBD–expressing cells, P4 completely lost its ability to repress transcription (Fig. 3, D and H). Taken together, P4–PR-mediated transrepression activity occurs at the level of transcription initiation, and the DNA-binding motif of PR appears to play a critical role. Moreover, PR-B appears to have more profound transrepressive activity than PR-A on IL-1β–mediated activation of proinflammatory gene expression. Because levels of PR expression in the four genetically modified hTERT-HM cell lines were comparable (Fig. 2B), the decreased repressive activities of PR-BmDBD, PR-AWT, and PR-AmDBD relative to PR-BWT cannot be attributed to differences in PR expression.

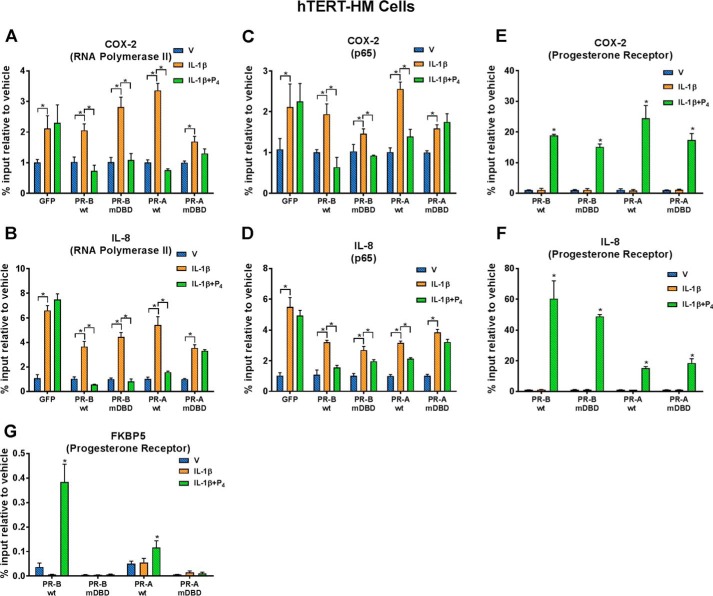

The PR DBD inhibits IL-1β-induced recruitment of NF-κB p65 and RNA Pol II to promoter regions of proinflammatory genes

To further define the mechanisms whereby P4–PR represses transcription of proinflammatory genes in human myometrial cells, ChIP was used to analyze the effects of IL-1β with or without P4 on recruitment of RNA Pol II, NF-κB p65, and PR to the COX-2 and IL-8 promoters. hTERT-HM cells stably expressing GFP or GFP conjugates of PR-AWT and PR-BWT and corresponding DBD mutants were cultured with or without IL-1β and with or without P4 for 40 min. In all cell lines, IL-1β significantly stimulated recruitment of RNA Pol II to a genomic region surrounding the COX-2 (Fig. 4A) and IL-8 (Fig. 4B) transcription start sites (TSS); co-treatment with P4 significantly decreased recruitment of RNA Pol II in cells stably expressing PR-BWT, PR-AWT, and PR-BmDBD. However, in cells expressing PR-AmDBD, P4 failed to inhibit recruitment of RNA Pol II (Fig. 4, A and B). Similar effects were observed for recruitment of NF-κB subunit p65 to NF-κB response elements of the COX-2 and IL-8 promoters (Fig. 4, C and D). Thus, whereas P4 significantly inhibited IL-1β–induced recruitment of p65 to the NF-κB response elements of the COX-2 and IL-8 promoters in PR-AWT–, PR-BWT–, and PR-BmDBD–expressing cells, the inhibitory effects of P4 were consistently not observed in hTERT-HM cells stably expressing PR-AmDBD (Fig. 4, C and D). Taken together, these findings suggest that P4–PR transrepression activity is mediated, in part, by inhibition of recruitment of endogenous NF-κB p65 and RNA Pol II to promoter regions of proinflammatory genes. Interestingly, when we used ChIP to analyze recruitment of PR-AWT, PR-BWT, PR-AmDBD, and PR-BmDBD to the genomic regions containing NF-κB response elements in the COX-2 (Fig. 4E) and IL-8 (Fig. 4F) promoters in the stably transfected hTERT-HM cells, PR recruitment was observed in cells treated with IL-1β + P4 (Fig. 4, E and F). Moreover, PR recruitment was unaffected by mutagenesis of the PR-A or PR-B DBD, compared with the corresponding PRWT (Fig. 4, E and F). By contrast, P4-mediated recruitment of PR-A and PR-B to the promoter of FKBP5, a direct PR target gene, was completely abrogated by mutation of their respective DBDs (Fig. 4G). This indicates that inhibitory effects of PR on proinflammatory and CAP gene expression are not mediated by direct DNA binding. Our findings, therefore, suggest that nuclear proteins that interact with the PR DBD may play an important role in P4–PR transrepression activity.

Figure 4.

Recruitment of endogenous RNA Pol II and NF-κB p65 to the COX-2 and IL-8 promoters was reduced by mutagenesis of the PR DBD in P4-treated hTERT-HM cells, whereas recruitment of PR was unaffected. ChIP analysis was used to study effects of P4 on recruitment of RNA polymerase II (A and B), p65 (C and D), and PR (E–G) to promoters of COX-2 (A, C, and E), IL-8 (B, D, and F), and FKBP5 (G) genes. The myometrial cells were treated with DMSO (V), IL-1β (10 ng/ml), or IL-1β plus P4 (100 nm) for 40 min prior to harvest and formalin treatment. qPCR was used to quantify the recruitment of RNA Pol II to the TSS and p65 and PR to the NF-κB-RE using specific primers (Table 1). -Fold recruitment is depicted as percentage input relative to the corresponding vehicle-treated sample. Data are the mean ± S.E. (error bars) of three replicate determinations for each treatment group. *, significant (p < 0.05) difference between samples.

GATAD2B (GATA zinc finger domain-containing 2B)/P66β selectively interacts with the PR DNA-binding domain

One of the mechanisms proposed to cause a decline in PR function during late gestation in myometrium is a decrease in PR coregulators (22). As mentioned, previous findings suggested that the DNA-binding motif of PR may serve an important role in P4–PR transrepression activity by interacting with nuclear corepressors (2). Based on the present findings, we hypothesized that whereas PR-BWT had the capacity to interact with such corepressors, the PR-A DBD mutant did not. Thus, to identify novel PR coregulators that mediate P4–PR anti-inflammatory activity, we sought to identify nuclear proteins that interacted with PR-BWT but not with PR-AmDBD.

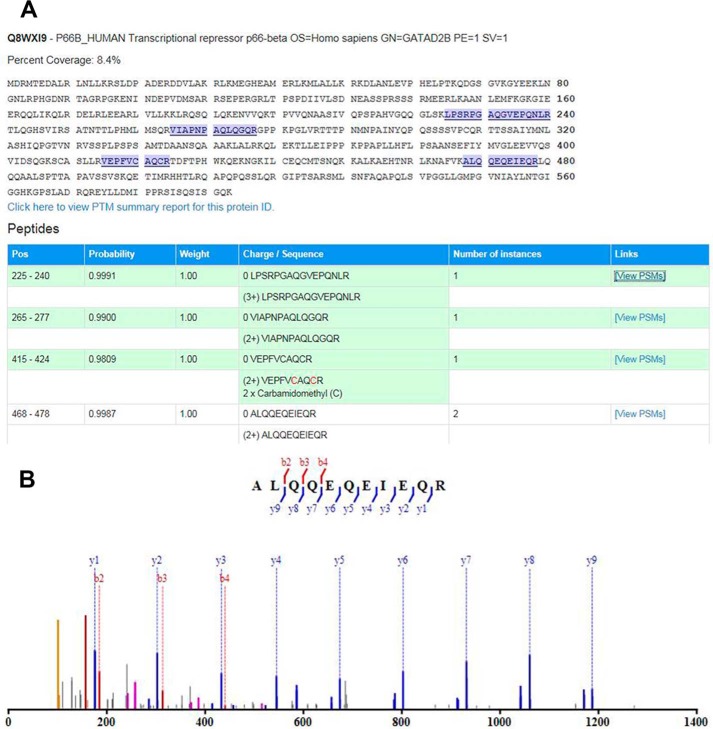

To obtain relatively large amounts of cell protein, we isolated nuclear extracts from HEK-293 cells stably expressing GFP alone, PR-BWT-GFP, and PR-AmDBD-GFP treated with IL-1β + P4 for 30 min. Antibodies to GFP were used to co-immunoprecipitate GFP-interacting proteins, followed by mass spectrometry analysis to identify proteins that had higher binding activity for PR-BWT versus PR-AmDBD (supplemental Table S1). Mass spectrometry values of PR-BWT– and PR-AmDBD–interacting proteins were normalized to those interacting with GFP alone. Proteins were selected with spectral counts >3 and a normalized ratio of PR-BWT versus PR-AmDBD of > 2.5. Using these criteria, 146 proteins were identified that interacted more strongly with PR-BWT than PR-AmDBD. Interacting proteins were further selected because of their known roles in transcriptional regulation. One of the proteins of potential interest that preferentially interacted with PR-BWT was GATAD2B, a component of the nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase (NuRD) complex (38, 39). Four unique peptides corresponding to GATAD2B were identified (Fig. 5A). The MS/MS spectrum of the most abundant GATAD2B peptide (residues 468–478) is shown (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

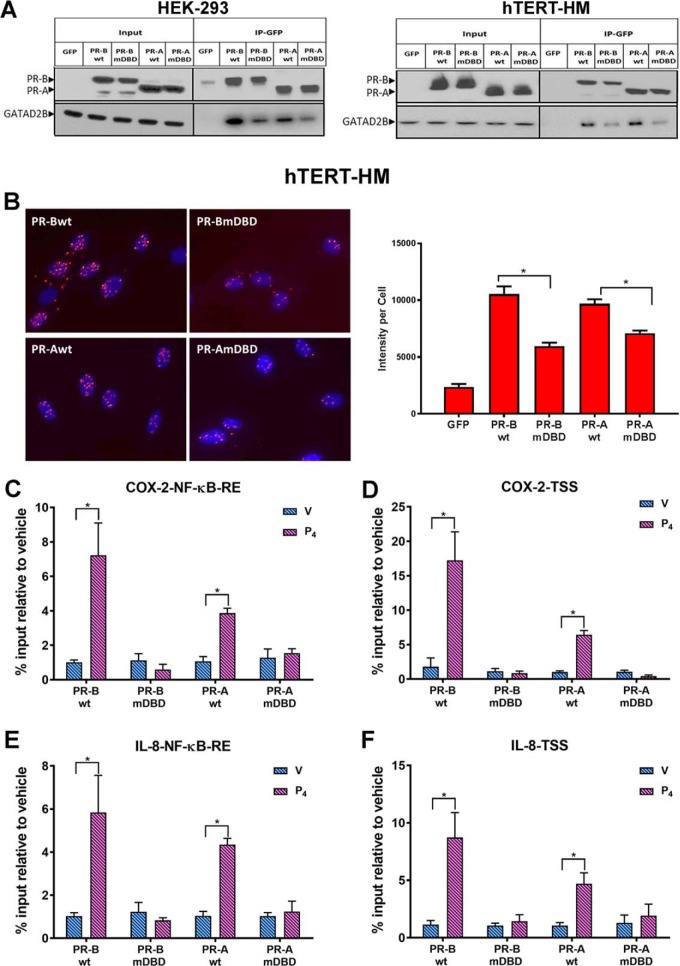

Mass spectrometry identification of GATAD2B/p66β as a PR-BWT–interacting protein. A, sequence of GATAD2B; four tryptic peptides identified by mass spectrometry analysis are highlighted. B, MS/MS spectrum of the most abundant tryptic peptide of GATAD2B, ALQQEQEIEQR, with fragment ion assignments labeled.

Using co-immunoprecipitation assays in HEK-293 (Fig. 6A, left) and hTERT-HM cells (Fig. 6A, right) stably transfected with WT and DBD mutant forms of PR-A and PR-B, we confirmed findings from mass spectrometry analysis indicating that PR-BWT specifically interacted with GATAD2B, whereas the association between PR-BmDBD and GATAD2B was weaker (Fig. 6A, left and right). Notably, PR-AWT also interacted more strongly with GATAD2B than did PR-AmDBD (Fig. 6A, left and right). To further validate the direct interaction between PR and GATAD2B in the hTERT-HM cells, a Duolink proximity ligation assay was used. As can be seen in Fig. 6B, when hTERT-HM cells were treated with IL-1β + P4 for 30 min, there was abundant red fluorescent signal in the nuclei of cells expressing PR-BWT or PR-AWT. This suggests a direct in vivo interaction of PRWT and GATAD2B. By contrast, the intensity of red fluorescent signal in cells expressing PR-BmDBD or PR-AmDBD was significantly lower compared with PRWT–expressing cells, suggesting that mutations in the DNA-binding motif of PR disrupted the interaction between PR and GATAD2B (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

PR interacts with GATAD2B and recruits GATAD2B to the COX-2 and IL-8 promoters in response to P4 treatment. A, co-immunoprecipitation assays (Co-IP) were performed in stably transfected HEK-293 (left) and in hTERT-HM (right) cells to validate interaction between PR and GATAD2B. Total cell proteins were isolated from cells stably expressing GFP-conjugated PR-BWT, PR-AWT, PR-BmDBD, or PR-AmDBD that had been treated with IL-1β (10 ng/ml) + P4 (1 nm) for 12 h and immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP magnetic beads. The eluted samples were collected for immunoblotting analysis of PR and GATAD2B with input as control. B, Duolink proximity ligation assays were used to detect the direct in vivo interaction between PR and GATAD2B. hTERT-HM myometrial cells stably expressing PR-AWT or PR-BWT or the corresponding DBD mutants were treated with IL-1β (10 ng/ml) + P4 (100 nm) for 40 min. Intensity of fluorescent signal per cell was calculated by normalizing red florescent PLA signals to cell number, which was quantified by DAPI signals (blue) in that image. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. for each treatment group (n = 6 fields/sample). C–F, ChIP assays were used to analyze the recruitment of GATD2B to an NF-κB response element or TSS in the COX-2 (C and D) and IL-8 gene (E and F) promoters. The myometrial cells were treated with DMSO (V), or P4 (100 nm) for 40 min. qPCR was used to quantify the recruitment of each factor to the promoter using specific primers (Table 1). -Fold recruitment is depicted as percentage input relative to the corresponding vehicle-treated sample. Data are the mean ± S.E. (error bars) of three replicate determinations for each treatment group. *, significant (p < 0.05) difference between samples.

Using ChIP, we observed that P4 treatment of hTERT-HM cells expressing PR-BWT or PR-AWT markedly enhanced recruitment of endogenous GATAD2B to the NF-κB response element (Fig. 6, C and E) and TSS (Fig. 6, D and F) regions of the COX-2 and IL-8 promoters. However, GATAD2B recruitment in response to P4 was abolished in hTERT-HM cells expressing the corresponding PR-A/-BmDBD (Fig. 6, C–F). Taken together, we have identified a nuclear protein, GATAD2B, which directly interacts with PR through the PR DNA-binding motif. Notably, PR also may exert its inhibitory effects by recruiting GATAD2B to transcription factors bound to other cis-acting elements (e.g. AP-1) in the proinflammatory gene promoters, not amplified by the primers used in this study. Previously, PR was reported to promote recruitment of corepressor p54nrb to an AP-1 response element in the Cx43/Gja1 promoter (23).

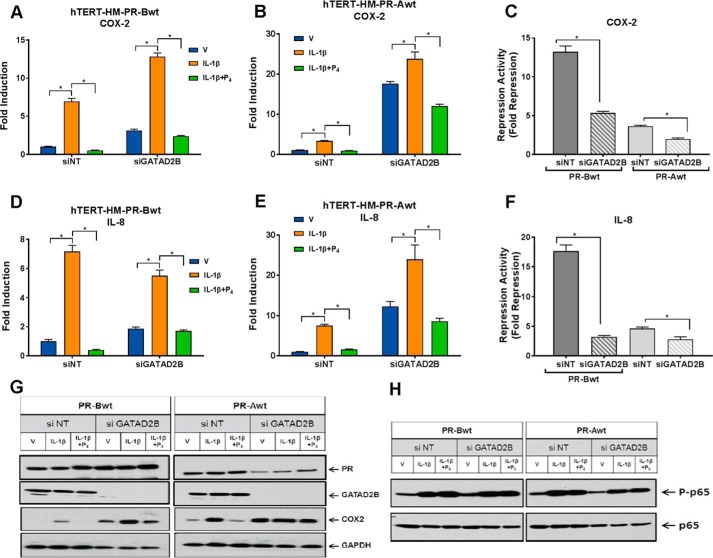

GATAD2B plays an important role in mediating P4–PR suppression of proinflammatory and CAP genes in the pregnant myometrium

To explore the role of GATAD2B in P4–PR–mediated transrepression activity, PR-BWT– and PR-AWT–expressing hTERT-HM cells were transfected with siRNA for GATAD2B or with a non-targeting siRNA, as control. The day after transfection, the cells were serum-starved by culturing them in DMEM/F-12 medium containing 1% charcoal-stripped serum for another 48 h. The cells were then treated with IL-1β with or without P4 for 2 h and harvested for mRNA expression analysis. As can be seen in Fig. 7 (A–F), in cells expressing PR-BWT or PR-AWT, siRNA-mediated knockdown of GATAD2B significantly reduced P4–PR–mediated repression of IL-1β–induced COX-2 (Fig. 7, A–C) and IL-8 (Fig. 7, D–F) mRNA expression compared with cells transfected with non-targeting siRNA. Knockdown of GATAD2B also blocked P4–PR–mediated suppression of endogenous COX-2 protein, which was clearly evident in cells transfected with nontargeting siRNA (Fig. 7G). Interestingly, we also observed that knockdown of endogenous GATAD2B resulted in up-regulation of the basal levels of IL-8 and COX-2 mRNA expression (Fig. 7, A–F) as well as levels of COX-2 protein expression (Fig. 7G). Notably, levels of NF-κB p65 phosphorylated at Ser-536, an NF-κB activation mark, were unaffected by GATAD2B knockdown (Fig. 7H), suggesting that the increased levels of COX-2 and IL-8 mRNA were not due to activation of NF-κB signaling. Together, these findings suggest that GATAD2B not only plays a role as corepressor of P4–PR–mediated anti-inflammatory activity, but also suppresses NF-κB target gene expression in a P4–PR–independent manner. The finding that knockdown of endogenous GATAD2B markedly reduced, but did not abolish, P4–PR repression of IL-1β and COX-2 expression suggests the possible role of other corepressors. A number of corepressors that interacted far more strongly with PR-BWT than with PR-AmDBD, identified by MS, including C-terminal binding proteins 1 and 2 and CNOT1 (supplemental Table S1), are the subject of ongoing investigations.

Figure 7.

GATAD2B plays an important role in P4-mediated transrepression activity. A–F, effects of siRNA-mediated knockdown of GATAD2B on P4 transrepression activity. hTERT-HM cells stably expressing PR-BWT or PR-AWT were transfected with 20 nm siRNAs targeting GATAD2B or non-targeting siRNA (siNT) control. Data are the mean ± S.E. (error bars) for each treatment group. *, significant (p < 0.05) difference between samples. GATAD2B siRNA transfection markedly reduced endogenous GATAD2B protein expression (G). After transfection, the cells were synchronized in phenol red-free medium supplemented with 1% charcoal-stripped FBS for another 48 h. The cells were then treated with DMSO vehicle (V), IL-1β (10 ng/ml), or IL-1β + P4 (100 nm). Effects of GATAD2B knockdown on COX-2 (A–C) and IL-8 (D–F) mRNA were analyzed after hormonal treatment for 2 h. C and F, repression activity was calculated by comparing the levels of mRNA expression in cells treated with IL-1β alone to mRNA expression after treatment with IL-1β + P4. Effects of siRNA-mediated knockdown of GATAD2B on COX-2 (G) and phospho-p65 at Ser-536 (H) proteins were assayed by immunoblotting after 4 or 2 h of hormonal treatment, respectively. Data are the mean ± S.E. of three replicate determinations for each treatment group. *, significant (p < 0.05) difference between samples.

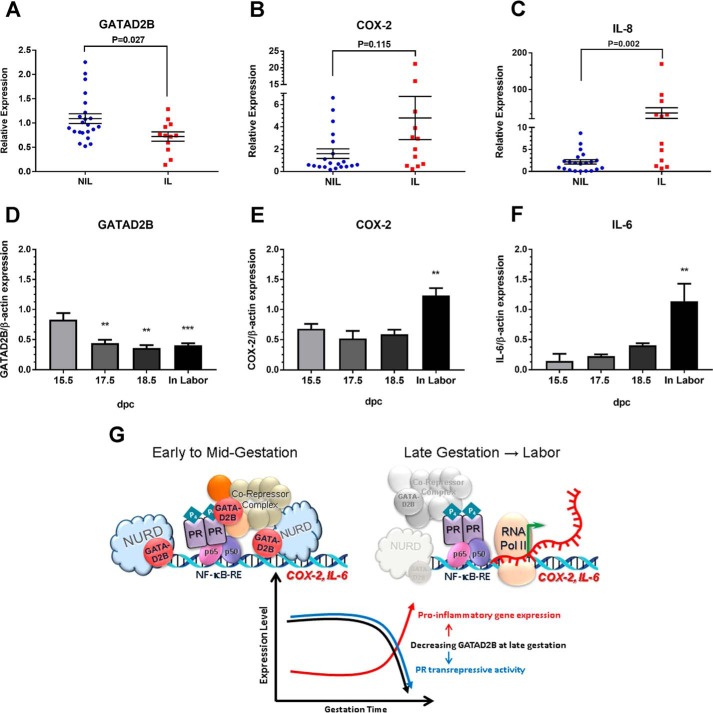

To determine the expression pattern of GATAD2B in human myometrium during pregnancy and labor, we used RT-qPCR to analyze mRNA levels in biopsies of term pregnant myometrium from women who were either in spontaneous labor (IL) or not in labor (NIL) at term. As can be seen in Fig. 8A, GATAD2B mRNA levels were significantly decreased in the IL samples compared with NIL samples. This was inversely correlated with IL-8 (Fig. 8C) mRNA levels, which were significantly increased in the IL myometrial tissues compared with NIL tissues. To determine whether this pattern of GATAD2B expression is conserved from humans to mice, we analyzed GATAD2B protein levels in myometrial tissues from timed pregnant mice at 15.5 days post coitum (dpc), 17.5 dpc, and 18.5 dpc and during active labor (19 dpc), signaled by the birth of the first pup. Shown are bar graphs representing combined scanned values from immunoblots of tissue lysates from three or more independent myometrial samples per gestational time point. GATAD2B protein levels were significantly reduced at 17.5 and 18.5 dpc and continued to decline during labor, compared with 15.5 dpc (Fig. 8D). In the same series of tissues, COX-2 (Fig. 8E) and IL-6 (Fig. 8F) protein levels remained relatively unchanged between 15.5 and 18.5 dpc and were up-regulated significantly during active labor. IL-8 levels are not shown because they were below detectable levels in the mouse myometrium. Taken together, our findings suggest that GATAD2B may play a key role in mediating P4–PR suppression of proinflammatory and CAP gene expression in the pregnant myometrium. A decline in myometrial GATAD2B expression during late gestation may contribute to the reduction in P4–PR–mediated anti-inflammatory activity and the increase in proinflammatory and CAP gene expression leading to parturition.

Figure 8.

GATAD2B is significantly decreased in human and mouse myometrium during labor. RT-qPCR was used to analyze GATAD2B (A), COX-2 (B), and IL-8 (C) mRNA expression in lower uterine segment myometrium of women in spontaneous labor (IL; n = 12) or not in labor (NIL; n = 20) at term. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to evaluate differences in GATAD2B, IL-8 and COX-2 expression between the NIL versus IL groups. p values are shown for each data set. Immunoblotting was used to analyze GATAD2B (D), COX-2 (E), and IL-6 (F) protein expression in three or more matched series of timed pregnant mouse myometrium between 15.5 dpc and labor (n ≥ 3 mice at each gestational time point). Each immunoblot was analyzed for β-actin as a control for loading and transfer. Scanned immunoblots were quantitated by densitometric analysis followed by correction for loading and transfer variances using ImageJ software. Combined data from scanned immunoblots are shown as bar graphs (arbitrary units (AU)). Data are the mean ± S.E. (error bars) for each group. For one-way analysis of variance, GATAD2B: F(3,12) = 10.57, p = 0.0011; COX-2: F(3,12) = 9.372, p = 0.0018; IL-6: F(3,8) = 8.219, p = 0.0079. Bonferroni's multiple comparison test was carried out post hoc using 15.5 dpc levels for comparison: **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; n = 4 mice at 15.5 dpc, 3 mice at 17.5 and 18.5 dpc, and 6 mice in labor. G, schematic model of the putative role of GATAD2B in suppression of myometrial contractile gene expression during pregnancy and labor.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to further define the mechanisms that mediate the inhibitory actions of P4–PR on expression of proinflammatory and CAP genes in the pregnant myometrium. We (15, 17, 40) and others (28, 41–43) previously obtained compelling evidence that P4–PR maintains uterine quiescence through its anti-inflammatory actions. We also demonstrated that P4–PR represses CAP gene expression via up-regulation of the inhibitory transcription factor, ZEB1 (18, 44). Recently, it was observed that P4 acting through PR-B recruits Jun/Jun homodimers and the corepressor complex, p54nrb–Sin3A–HDAC, to the promoter of the CAP gene CX43 (45) to inhibit its expression. Near term, it is suggested that the increased metabolism of P4 by 20α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (29) and an inflammation-induced increase in PR-A/PR-B ratio (26, 46, 47) causes PR-A to become unliganded and to recruit Fra2/JunD heterodimers (45). This switch may allow PR-A to serve as an activator of CX43 expression. However, the detailed molecular mechanism(s) by which PR exerts all of its repressive actions on proinflammatory and CAP genes remains incompletely defined.

It was first of interest to identify the domain(s) of PR required for its anti-inflammatory actions. Using an NF-κB–mediated reporter assay in HEK-293 cells transiently transfected with PRWT and PR-A and PR-B mutants, we observed that PR sumoylation, dimerization, and DNA-binding motifs all play an important role in P4-mediated repression of NF-κB transactivation. However, mutations in the PR DBD caused the greatest decline in PR anti-inflammatory activity. To further study the role of the DNA-binding motif in P4–PR–mediated transrepression activity, we created hTERT-HM immortalized myometrial cells stably expressing wild-type and DNA-binding domain mutant forms of PR-A and PR-B. Interestingly, we found that P4–PR repressed proinflammatory and CAP gene expression at the level of transcription initiation; this involved a block in IL-1β-induced recruitment of NF-κB p65 and RNA Pol II to the IL-8 and COX-2 promoters. Whereas both PR-BWT and PR-AWT had the ability to repress IL-1β induced initiation of transcription, PR-BWT had significantly higher repressive activity compared with PR-AWT. Furthermore, whereas P4-mediated repression of IL-1β-induced mRNA and hnRNA expression was moderately decreased in hTERT-HM cells expressing PR-BmDBD, in cells expressing PR-AmDBD, P4 completely lost its transrepression activity. Similarly, ChIP analysis revealed that in hTERT-HM cells expressing PR-AmDBD, the effect of P4 to inhibit p65 and Pol II recruitment to the COX-2 and IL-8 promoters observed in the other PR-expressing cell lines was prevented. Taken together, these results suggest that the unique 164-amino acid sequence at the N terminus of PR-B (BUS region), which is lacking in PR-A, plays an important role in P4-mediated transrepression function. The BUS region may act cooperatively with the DBD (common to PR-A and PR-B) to promote PR-B-mediated suppression of proinflammatory genes. ChIP revealed that both WT and DBD mutant forms of PR-A and PR-B were equivalently recruited to promoters of COX-2 and IL-8 genes in cells treated with IL-1β + P4. By contrast, P4-mediated recruitment of PR-A and PR-B to the promoter of FKBP5, a direct target of PR, was abrogated by mutation of their respective DBDs (Fig. 4G). These compelling findings suggest that the inhibitory effects of P4–PR on inflammatory gene expression are not mediated by direct DNA binding, but rather by tethering to other transcription factors. We hypothesize that the loss of transrepression activity of the PR-A DBD mutant resulted from decreased interaction of PR with proteins that contain a corepressor function.

To identify novel nuclear proteins that interact with the PR DNA-binding motif and serve a corepressor function for P4–PR–mediated anti-inflammatory actions, mass spectrometry (complex mixture ID) analysis was utilized. To select relevant proteins that interact with the PR DNA-binding motif and serve as PR corepressors in myometrial tissues, we used three criteria to narrow down candidates: 1) for PR DNA-binding motif–dependent interactions, we selected proteins that manifested ≥ 3-fold greater binding to PR-BWT compared with PR-AmDBD; 2) to identify PR interacting proteins with known corepressor function, the DAVID bioinformatics resource (48, 49) was used; and 3) to identify proteins known to be expressed in human myometrium, RNA expression levels of proteins of interest were analyzed using published data sets (50). GATAD2B was one of the nuclear proteins identified using all three criteria.

Human GATAD2B, also known as p66β, is a member of the transcription repressor Mi-2/nucleosome-remodeling and deacetylase (NuRD) complex (51). The NuRD complex contains six major members, including CHD3/4 ATPase, histone deacetylases 1/2 (HDAC1/2), methyl-CpG-binding domain 2/3 (MBD2/3), retinoblastoma-binding proteins 7/4 (RBBP7/4), metastasis-associated 1/2/3 (MTA1/2/3), and p66α/β. The NuRD complex is responsible for silencing of methylated genes by nucleosome remodeling and histone deacetylation. The N-terminal conserved CR1 region of GATAD2B is required for interaction with MBD2/3, MTA2, HDAC1/2, and RBBP7/4 and also plays an important role in GATAD2B-mediated repression activity (38, 39, 52). Using the Duolink proximity ligation assay, we observed a direct protein–protein interaction between PR and GATAD2B in human myometrial cells; mutations in the PR DNA-binding motif not only disrupted the PR-GATAD2B physical interaction but also abrogated P4-induced recruitment of GATAD2B to the COX-2 and IL-8 promoters. Thus, these findings suggest that the PR DNA-binding motif plays an important role in PR–GATAD2B interaction. In hTERT-HM cells, knockdown of GATAD2B expression by RNA interference resulted in a significant loss of P4–PR–mediated repression activity, supporting the functional role of GATAD2B in P4–PR–mediated transrepression. Interestingly, knockdown of GATAD2B also caused an increase in endogenous levels of COX-2 and IL-8 mRNA expression in untreated hTERT-HM cells. However, levels of NF-κB p65 phosphorylated at Ser-536, an NF-κB activation mark, were unaffected by GATAD2B knockdown (Fig. 7H), suggesting that the increased levels of COX-2 and IL-8 mRNA were not caused by activation of NF-κB signaling. Collectively, these data suggest that GATAD2B also may play a role in repression of NF-κB–mediated gene expression independent of P4 and PR.

As summarized in Fig. 8G, we have identified a novel PR-interacting factor, GATAD2B, which binds to the DNA-binding motif of PR tethered to inflammatory transcription factors (e.g. NF-κB) bound to the promoter regions of proinflammatory genes (e.g. COX-2 and IL-8). We propose that GATAD2B serves a role in P4-mediated transrepression of these proinflammatory genes by recruiting transcriptional repressors (e.g. the NuRD complex). Importantly, GATAD2B expression levels were found to be reduced in myometrial biopsies of women in labor, compared with not in labor, and in pregnant mouse myometrium during late gestation and labor. Thus, we suggest that decreased expression of GATAD2B causes a derepression of proinflammatory and CAP genes and contributes to the functional P4–PR withdrawal, leading to parturition (Fig. 8G).

Experimental procedures

Reagents and cell culture

Human immortalized myometrial (hTERT-HM) cells were maintained in DMEM/F-12 (Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS. HEK-293 cells were maintained in DMEM (Life Technologies) containing 7% (v/v) FBS. Cells were cultured and grown in a 95% air, 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C. For RNA and protein expression experiments, cells were seeded in maintenance medium; the next day, cells were incubated with phenol red-free medium supplemented with 1% charcoal-stripped serum (Life Technologies) for another 24 h prior to treatment. For treatment with various reagents, cells were incubated in phenol red–free medium with 1% charcoal-stripped FBS for the times indicated. Progesterone (Sigma), IL-1β (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA), and all other reagents used were of the highest quality available from commercial sources. Antibodies used for Western blotting included progesterone receptor (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), GATAD2B (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX), and GAPDH and COX-2 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK).

Cloning and generation of stably transfected PR-expressing cells

PR-BWT expression vector was a gift from Dr. Donald McDonnell at Duke University. hPR-AWT was generated by PCR using hPR-B as a template with primers to amplify the region from the first ATG of PR-A to the stop codon. PR-B DBD and PR-A DBD mutants (PRmDBD) carrying a triple mutation (G584E/S585G/V589A) in the P-box were generated using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA).

To generate recombinant lentiviruses, PR-BWT, PR-BmDBD, PR-AWT, and PR-AmDBD were subcloned into pLVX-GFP IRES Puro vector (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) to create N-terminal GFP-conjugated PR expression constructs. High-titer lentiviruses were generated according to the Lenti-X system specifications (Clontech). pLVX-GFP IRES Puro plasmid was used to create a “GFP only” recombinant virus and served as a control.

To generate cells stably expressing PR, human immortalized myometrial cells (hTERT-HM cells) (36), or HEK-293 cells were infected with the recombinant lentiviruses. Viral suspensions were titrated by infecting a fixed number of cells with various volumes of the viral suspension. The proportion of infected cells was determined using fluorescence microscopy for the detection of GFP expression. Cells with a low proportion of infection (10–30%) were selected for further study, because they contained approximately one integrant per host genome, thereby minimizing overexpression. GFP-positive cells were isolated by flow cytometry and used to establish the cell lines used thereafter. PR protein expression levels in the stable cell lines were routinely verified by immunoblotting (18) using PR-A/B rabbit mAb (Cell Signaling, A/B (D8Q2J) XP®, catalog no. 8757).

Reporter assay and RNA interference

For luciferase reporter assays, HEK-293 cells were seeded in 24-well plates and transfected using FuGENE HD transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science) with luciferase reporter constructs pGL4.32[luc2P/NF-κB-RE/Hygro] (Promega, Madison, WI) and Renilla luciferase plasmid to normalize for transfection efficiency. One day post-transfection, cells were treated with DMSO, IL-1β (10 ng/ml), or IL-1β plus P4 (100 nm) for 6 h. Cells from each experiment were harvested in passive lysis buffer (Promega). Firefly luciferase and Renilla luciferase activities were assayed using a Dual-Luciferase assay system (Promega). Relative luciferase activities were calculated by normalizing firefly luciferase activity to Renilla luciferase activity within the same samples to correct for transfection efficiencies.

For RNAi experiments, siRNA oligonucleotides against human GATAD2B and silencer-negative control oligonucle-otides purchased from Life Technologies were transfected using the Neon® transfection system (Life Technologies).

RT-qPCR assay

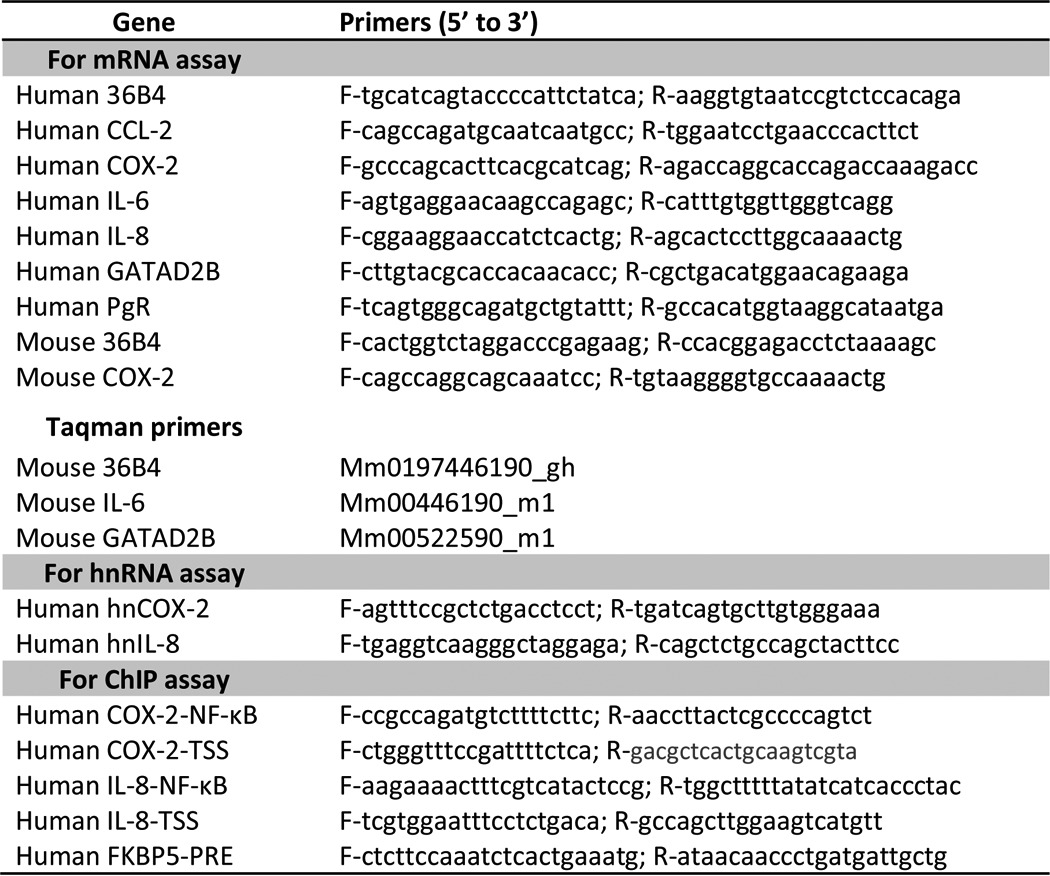

Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Foster City, CA). Approximately 1 μg of RNA was reverse-transcribed using a QuantiTect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen). For quantitative analysis of mRNA, the CFX384TM real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad) was used along with iTaq SYBR Green Supermix with ROX (Bio-Rad) or Taqman PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) for detection of PCR products. Relative arbitrary units were determined by comparative cycle times (Ct) of each transcript to Ct of acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein P0 (36B4) (endogenous control) and calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Taqman primers were obtained from Applied Biosystems. Primer sets are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sets

ChIP

ChIP assays were performed using the ChIP assay kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA), according to the manufacturer's recommendations and as described previously (15). Antibodies used for the ChIP assay included human PR-A/-B, p65 NF-κB subunit, non-immune IgG (Cell Signaling), RNA Pol II (Millipore), and GATAD2B (Bethyl Laboratories). Purified DNA was analyzed by qPCR. Primer sets are listed in Table 1.

Duolink proximity ligation assay

hTERT-HM cells were cultured on collagen-coated coverslips and treated with IL-1β (10 ng/ml) + P4 (100 nm) for 30 min. The cells were then incubated with blocking solution (provided with Duolink In Situ PLA probe, Sigma) for 30 min at 37 °C, followed by a 2-h incubation at 37 °C with primary mouse antibody against human PR (R&D Systems) and rabbit antibody against human GATAD2B (Bethyl Laboratories). Cells were washed twice using Wash Buffer A (Duolink In Situ Reagents, Sigma) and incubated with the appropriate anti-species secondary antibodies to which oligonucleotides had been conjugated (anti-rabbit PLA probe PLUS and anti-mouse PLA probe MINUS, Sigma) for 1 h at 37 °C. The cells were then treated with Duolink ligation-ligase solution for 30 min at 37 °C. Finally, cells were incubated with the Duolink amplification-polymerase solution for 60 min at 37 °C, followed by washing and mounting on slides with Duolink mounting medium with DAPI. Images were captured using a Nikon TE2000-U fluorescence microscope. Six images were acquired for each sample and quantified using BlobFinder software (53). Briefly, images were converted to 8-bit for segmentation for each channel. Intensity per cell was calculated by expressing normalized red florescent PLA signals with cell number, which was determined by DAPI signals in that image.

Human subjects and tissue acquisition

Lower uterine segment myometrial tissues were biopsied from pregnant women undergoing repeat cesarean section. Informed consent was obtained in writing from each woman before surgery using protocols approved by the institutional review board of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in accordance with the Donors Anatomical Gift Act of the State of Texas. Myometrial biopsies were collected from two groups of patients: 1) pregnant women who underwent cesarean section prior to the onset of labor at term with no evidence of infection and 2) pregnant women in active labor at term undergoing cesarean section. Myometrial smooth muscle was dissected from each biopsy, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C for subsequent protein and mRNA analysis.

Timed-pregnant mice and myometrial tissue collection

All animal studies were conducted in compliance with protocols approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Outbred virgin CD1/ICR mice were acquired from Harlan Laboratories (Harlan USA, Houston, TX). Mice were time-mated as described previously (54). Briefly, males and females were housed together between 1800 and 0600 h. Pregnancy was determined by the presence of a vaginal plug that morning and designated as 0.5 dpc. Mice were maintained on a diurnal 12-h light/12-h dark cycle with access to standard chow and water ad libitum. Timed-pregnant mice were euthanized at ∼1000 h on 15.5, 16.5, 17.5, and 18.5 dpc and during labor (IL) following the delivery of the first pup using isofluorane anesthetic inhalation (Baxter Healthcare Corp., San Juan, Puerto Rico) and cervical dislocation. Maternal myometrial tissues were isolated as described (54). All tissues were flash-frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C until analyzed.

Immunoblot analysis

Whole cell protein extracts were isolated from flash-frozen myometrial tissues homogenized in 1× radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing proteinase and protease inhibitors (Sigma). Homogenates were centrifuged at 5000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and supernatants were stored at −80 °C. Protein concentrations were quantified using the Bradford assay (BCA Protein Assay Kit, Pierce). Equivalent amounts of myometrial protein were added to 4× NuPage LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen). Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions (Bio-Rad) and transferred onto a PVDF membrane using the XCell SureLock electrophoresis system (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in 5% (w/v) nonfat dry milk in 1× PBS-T (PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20), washed with 1× PBS-T, and incubated at 4 °C overnight with primary antibody against GATAD2B/p66β (A301-281A, Bethyl Laboratories; 1:750), IL-6 (sc-57315, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:1200), COX-2 (ab15191, Abcam; 1:1000), and β-actin (ab8227, Abcam; 1:5000), to correct for loading and transfer. Membranes were washed and incubated for 1 h at room temperature in blocking buffer containing horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit-IgG (ab′)2 fragment (GE NA9340V, GE Healthcare), for GATAD2B, COX-2, and β-actin detection, or with m-IgGκ BP-HRP (sc-516102, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for IL-6 detection. Enhanced chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific) was used according to the manufacturer's protocol. Because GATAD2B (66 kDa) and COX-2 (69 kDa) proteins are of similar molecular weight, membranes were stripped following GATAD2B immunoblotting and reprobed using antibody against COX-2. Densitometric analyses of immunoreactive bands were quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). Corrected values from scanned immunoblots of myometrial GATAD2B, COX-2, and IL-6 protein levels during late gestation and labor were combined and analyzed.

Mass spectrometry

To identify novel nuclear proteins that interact with the PR DNA-binding motif and serve a corepressor function for P4–PR–mediated anti-inflammatory actions, we utilized mass spectrometry analysis of HEK-293 cells stably expressing GFP-conjugated PR-BWT or PR-AmDBD treated with IL-1β (10 ng/ml) plus P4 (100 nm) for 30 min. The stable HEK-293 cell lines were utilized for these studies because hTERT-HM cells grow slowly in culture and would probably yield insufficient amounts of nuclear protein. Moreover, in cotransfection experiments, the HEK-293 cells respond to P4 and IL-1β in a manner similar to the stably transfected hTERT-HM cells (i.e. PR-BWT markedly represses NF-κB transcriptional activity, whereas PR-AmDBD lacks this repressive effect) (Fig. 1). Nuclear protein fractions were isolated from these cell lines, as described (55), and immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP magnetic beads (MBL International, Nagoya, Japan) at 4 °C for 24 h. After washing the beads, supernatants were collected, and the immunoprecipitated nuclear proteins were loaded and run 5–10 mm into the resolving portion of an SDS–polyacrylamide gel. The gel was stained with SimplyBlue SafeStain (Invitrogen). The stained area for each sample was then excised and sent to the University of Texas Southwestern Proteomics Core for complex mixture ID analysis. Gel bands were digested overnight with trypsin (Promega) following reduction and alkylation with DTT and iodoacetamide (Sigma-Aldrich). Digested samples were extracted from the gel and cleaned by solid-phase extraction with Oasis HLB plates (Waters). The samples were then reconstituted and analyzed by LC/MS/MS, using a Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo) coupled to an Ultimate 3000 RSLC-Nano liquid chromatography system (Dionex). Proteins interacting with PR-BWT or PR-AmDBD were identified and quantified as described below.

To analyze MS data, raw MS data files were converted to a peak list format and analyzed using CPFP (central proteomics facilities pipeline) version 2.0.3 (56, 57). Peptide identification was performed using the X!Tandem (58) and open MS search algorithm (OMSSA) (59) search engines against the human database from Uniprot. Fragment and precursor tolerances of 20 ppm and 0.1 Da were specified; three missed cleavages were allowed. Carbamidomethylation of Cys was set as a fixed modification, and oxidation of Met was set as a variable modification. Label-free quantitation of proteins interacting with PR-BWT or PR-AmDBD across samples was performed using SINQ (spectral index quantitation software)-normalized spectral index software (60).

Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) assays

Co-IP assays were performed to validate interactions in vivo between PR and GATAD2B. Total cell proteins were isolated in cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 9803S) from hTERT-HM or HEK-293 cells stably expressing GFP-conjugated PR-BWT, PR-AWT, PR-BmDBD, or PR-AmDBD that were previously treated with IL-1β (10 ng/ml) + P4 (1 nm) for 12 h. Cell extracts (1500 μg) were then precleared with 80 μl of protein A/G PLUS-agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., catalog no. sc-2003) for 30 min and immunoprecipitated with 100 μl of anti-GFP magnetic beads for 24 h (MBL International Corporation, catalog no. D153-11). The beads were washed with cell lysis buffer three times and three times with lysis buffer containing 2 mm DTT and 500 mm NaCl. The eluted samples were then subjected to immunoblotting analysis of PR and GATAD2B using antibodies for PR-A/B (Cell Signaling, catalog no. 8757) and GATAD2B (Bethyl Laboratories, catalog no. A301-281A) with input as control.

Data analysis

Differences between groups were analyzed using either Student's t test or one-way analysis of variance, where appropriate, using GraphPad Prism version 7.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Statistical significance was set as a p value of <0.05.

Author contributions

C.-C. C. contributed to the conceptual design, conducted the experiments, interpreted the data, and wrote the paper. A. P. M. analyzed expression of GATAD2B, COX-2, and IL-6 proteins in pregnant mouse myometrium (Fig. 8, D–F), reviewed mass spectrometry data with the Proteomics Core, edited the manuscript, extended statistical analyses, and revised figures. I. H. analyzed expression of PR (Fig. 2B) and performed co-immunoprecipitation assays in stably transfected HEK-293 and hTERT-HM cell lines (Fig. 6A). W.-R. L. conducted the Duolink proximity ligation assays in hTERT-HM cells (Fig. 6B). C. R. M. contributed to the conceptual design of the studies, reviewed and interpreted the data, and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Andrew Lemoff (University of Texas Southwestern Proteomics Core) for analysis of the mass spectrometry data as well as helpful discussion regarding this work. We also thank Dr. Linda Hynan (Division of Biostatistics, Department of Clinical Sciences) for help in statistical analysis of data from human myometrial samples. The UT Southwestern Proteomics Core is supported by the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (Grant RP120613).

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants P01 HD011149 and P01 HD087150 (to C. R. M.) and by Prematurity Research Initiative Grant 21-FY14-146 from the March of Dimes Foundation (to C. R. M.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains supplemental Table S1.

- P4

- progesterone

- PR

- progesterone receptor

- hTERT-HM cells

- human telomerase reverse transcriptase immortalized human myometrial cell line

- TSS

- transcription start site(s)

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- EU

- 5-ethynyl uridine

- DBD

- DNA-binding domain

- mDBD

- DNA-binding domain mutant

- Pol

- polymerase

- NuRD

- nucleosome-remodeling and deacetylase

- hnRNA

- heterogeneous nuclear RNA

- IL

- in spontaneous labor

- NIL

- not in labor

- dpc

- days post-coitum

- IP

- immunoprecipitation.

References

- 1. Faivre E. J., Daniel A. R., Hillard C. J., and Lange C. A. (2008) Progesterone receptor rapid signaling mediates serine 345 phosphorylation and tethering to specificity protein 1 transcription factors. Mol. Endocrinol. 22, 823–837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kalkhoven E., Wissink S., van der Saag P. T., and van der Burg B. (1996) Negative interaction between the RelA(p65) subunit of NF-κB and the progesterone receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 6217–6224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tseng L., Tang M., Wang Z., and Mazella J. (2003) Progesterone receptor (hPR) upregulates the fibronectin promoter activity in human decidual fibroblasts. DNA Cell Biol. 22, 633–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lonard D. M., and O'Malley B. W. (2006) The expanding cosmos of nuclear receptor coactivators. Cell 125, 411–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cox S. M., Casey M. L., and MacDonald P. C. (1997) Accumulation of interleukin-1β and interleukin-6 in amniotic fluid: a sequela of labour at term and preterm. Hum. Reprod. Update 3, 517–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thomson A. J., Telfer J. F., Young A., Campbell S., Stewart C. J., Cameron I. T., Greer I. A., and Norman J. E. (1999) Leukocytes infiltrate the myometrium during human parturition: further evidence that labour is an inflammatory process. Hum. Reprod. 14, 229–236 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Condon J. C., Jeyasuria P., Faust J. M., and Mendelson C. R. (2004) Surfactant protein secreted by the maturing mouse fetal lung acts as a hormone that signals the initiation of parturition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 4978–4983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Osman I., Young A., Ledingham M. A., Thomson A. J., Jordan F., Greer I. A., and Norman J. E. (2003) Leukocyte density and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in human fetal membranes, decidua, cervix and myometrium before and during labour at term. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 9, 41–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Romero R., Espinoza J., Gonçalves L. F., Kusanovic J. P., Friel L., and Hassan S. (2007) The role of inflammation and infection in preterm birth. Semin. Reprod. Med. 25, 21–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Condon J. C., Hardy D. B., Kovaric K., and Mendelson C. R. (2006) Upregulation of the progesterone receptor (PR)-C isoform in laboring myometrium by activation of NF-κB may contribute to the onset of labor through inhibition of PR function. Mol. Endocrinol. 20, 764–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chow L., and Lye S. J. (1994) Expression of the gap junction protein connexin-43 is increased in the human myometrium toward term and with the onset of labor. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 170, 788–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fuchs A. R., Fuchs F., Husslein P., and Soloff M. S. (1984) Oxytocin receptors in the human uterus during pregnancy and parturition. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 150, 734–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Olson D. M. (2003) The role of prostaglandins in the initiation of parturition. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 17, 717–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Soloff M. S., Izban M. G., Cook D. L. Jr, Jeng Y. J., and Mifflin R. C. (2006) Interleukin-1-induced NF-κB recruitment to the oxytocin receptor gene inhibits RNA polymerase II-promoter interactions in cultured human myometrial cells. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 12, 619–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hardy D. B., Janowski B. A., Corey D. R., and Mendelson C. R. (2006) Progesterone receptor (PR) plays a major anti-inflammatory role in human myometrial cells by antagonism of NF-κB activation of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) expression. Mol. Endocrinol. 20, 2724–2733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee Y., Sooranna S. R., Terzidou V., Christian M., Brosens J., Huhtinen K., Poutanen M., Barton G., Johnson M. R., and Bennett P. R. (2012) Interactions between inflammatory signals and the progesterone receptor in regulating gene expression in pregnant human uterine myocytes. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 16, 2487–2503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen C. C., Hardy D. B., and Mendelson C. R. (2011) Progesterone receptor inhibits proliferation of human breast cancer cells via induction of MAPK phosphatase 1 (MKP-1/DUSP1). J. Biol. Chem. 286, 43091–43102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Renthal N. E., Chen C. C., Williams K. C., Gerard R. D., Prange-Kiel J., and Mendelson C. R. (2010) miR-200 family and targets, ZEB1 and ZEB2, modulate uterine quiescence and contractility during pregnancy and labor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 20828–20833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Virgo B. B., and Bellward G. D. (1974) Serum progesterone levels in the pregnant and postpartum laboratory mouse. Endocrinology 95, 1486–1490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Challis J. R. G., Matthews S. G., Gibb W., and Lye S. J. (2000) Endocrine and paracrine regulation of birth at term and preterm. Endocr. Rev. 21, 514–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pointis G., Rao B., Latreille M. T., Mignot T. M., and Cedard L. (1981) Progesterone levels in the circulating blood of the ovarian and uterine veins during gestation in the mouse. Biol. Reprod. 24, 801–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Condon J. C., Jeyasuria P., Faust J. M., Wilson J. W., and Mendelson C. R. (2003) A decline in progesterone receptor coactivators in the pregnant uterus at term may antagonize progesterone receptor function and contribute to the initiation of labor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 9518–9523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dong X., Yu C., Shynlova O., Challis J. R., Rennie P. S., and Lye S. J. (2009) p54nrb is a transcriptional corepressor of the progesterone receptor that modulates transcription of the labor-associated gene, connexin 43 (Gja1). Mol. Endocrinol. 23, 1147–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Leite R. S., Brown A. G., Strauss J. F. 3rd (2004) Tumor necrosis factor-α suppresses the expression of steroid receptor coactivator-1 and -2: a possible mechanism contributing to changes in steroid hormone responsiveness. FASEB J. 18, 1418–1420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xie N., Liu L., Li Y., Yu C., Lam S., Shynlova O., Gleave M., Challis J. R., Lye S., and Dong X. (2012) Expression and function of myometrial PSF suggest a role in progesterone withdrawal and the initiation of labor. Mol. Endocrinol. 26, 1370–1379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Merlino A. A., Welsh T. N., Tan H., Yi L. J., Cannon V., Mercer B. M., and Mesiano S. (2007) Nuclear progesterone receptors in the human pregnancy myometrium: evidence that parturition involves functional progesterone withdrawal mediated by increased expression of progesterone receptor-A. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92, 1927–1933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mesiano S., Chan E. C., Fitter J. T., Kwek K., Yeo G., and Smith R. (2002) Progesterone withdrawal and estrogen activation in human parturition are coordinated by progesterone receptor A expression in the myometrium. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 87, 2924–2930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tan H., Yi L., Rote N. S., Hurd W. W., and Mesiano S. (2012) Progesterone receptor-A and -B have opposite effects on proinflammatory gene expression in human myometrial cells: implications for progesterone actions in human pregnancy and parturition. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97, E719–E730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Williams K. C., Renthal N. E., Condon J. C., Gerard R. D., and Mendelson C. R. (2012) MicroRNA-200a serves a key role in the decline of progesterone receptor function leading to term and preterm labor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 7529–7534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Glass C. K., and Saijo K. (2010) Nuclear receptor transrepression pathways that regulate inflammation in macrophages and T cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 365–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Abdel-Hafiz H., Dudevoir M. L., and Horwitz K. B. (2009) Mechanisms underlying the control of progesterone receptor transcriptional activity by SUMOylation. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 9099–9108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Abdel-Hafiz H. A., and Horwitz K. B. (2012) Control of progesterone receptor transcriptional synergy by SUMOylation and deSUMOylation. BMC. Mol. Biol. 13, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Daniel A. R., Faivre E. J., and Lange C. A. (2007) Phosphorylation-dependent antagonism of sumoylation derepresses progesterone receptor action in breast cancer cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 21, 2890–2906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Quiles I., Millán-Ariño L., Subtil-Rodríguez A., Miñana B., Spinedi N., Ballaré C., Beato M., and Jordan A. (2009) Mutational analysis of progesterone receptor functional domains in stable cell lines delineates sets of genes regulated by different mechanisms. Mol. Endocrinol. 23, 809–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li H., Wittwer T., Weber A., Schneider H., Moreno R., Maine G. N., Kracht M., Schmitz M. L., and Burstein E. (2012) Regulation of NF-κB activity by competition between RelA acetylation and ubiquitination. Oncogene 31, 611–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Condon J., Yin S., Mayhew B., Word R. A., Wright W. E., Shay J. W., and Rainey W. E. (2002) Telomerase immortalization of human myometrial cells. Biol. Reprod. 67, 506–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Williams K. C., Renthal N. E., Gerard R. D., and Mendelson C. R. (2012) The microRNA (miR)-199a/214 cluster mediates opposing effects of progesterone and estrogen on uterine contractility during pregnancy and labor. Mol. Endocrinol. 26, 1857–1867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Brackertz M., Gong Z., Leers J., and Renkawitz R. (2006) p66α and p66β of the Mi-2/NuRD complex mediate MBD2 and histone interaction. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 397–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Allen H. F., Wade P. A., and Kutateladze T. G. (2013) The NuRD architecture. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 70, 3513–3524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hardy D. B., and Mendelson C. R. (2006) Progesterone receptor (PR) antagonism of the inflammatory signals leading to labor. Fetal Maternal Med. Rev. 17, 281–289 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Siiteri P. K., and Stites D. P. (1982) Immunologic and endocrine interrelationships in pregnancy. Biol. Reprod. 26, 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tibbetts T. A., Conneely O. M., and O'Malley B. W. (1999) Progesterone via its receptor antagonizes the pro-inflammatory activity of estrogen in the mouse uterus. Biol. Reprod. 60, 1158–1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shynlova O., Lee Y. H., Srikhajon K., and Lye S. J. (2013) Physiologic uterine inflammation and labor onset: integration of endocrine and mechanical signals. Reprod. Sci. 20, 154–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Renthal N. E., Williams K. C., and Mendelson C. R. (2013) MicroRNAs: mediators of myometrial contractility during pregnancy and labour. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 9, 391–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nadeem L., Shynlova O., Matysiak-Zablocki E., Mesiano S., Dong X., and Lye S. (2016) Molecular evidence of functional progesterone withdrawal in human myometrium. Nat. Commun. 7, 11565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Peters G. A., Yi L., Skomorovska-Prokvolit Y., Patel B., Amini P., Tan H., and Mesiano S. (2017) Inflammatory stimuli increase progesterone receptor-A stability and transrepressive activity in myometrial cells. Endocrinology 158, 158–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Amini P., Michniuk D., Kuo K., Yi L., Skomorovska-Prokvolit Y., Peters G. A., Tan H., Wang J., Malemud C. J., and Mesiano S. (2016) Human parturition involves phosphorylation of progesterone receptor-A at serine-345 in myometrial cells. Endocrinology 157, 4434–4445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Huang D. W., Sherman B. T., Tan Q., Kir J., Liu D., Bryant D., Guo Y., Stephens R., Baseler M. W., Lane H. C., and Lempicki R. A. (2007) DAVID Bioinformatics Resources: expanded annotation database and novel algorithms to better extract biology from large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W169–W175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Huang da W., Sherman B. T., and Lempicki R. A. (2009) Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 4, 44–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chan Y. W., van den Berg H. A., Moore J. D., Quenby S., and Blanks A. M. (2014) Assessment of myometrial transcriptome changes associated with spontaneous human labour by high-throughput RNA-seq. Exp. Physiol. 99, 510–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Torchy M. P., Hamiche A., and Klaholz B. P. (2015) Structure and function insights into the NuRD chromatin remodeling complex. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 72, 2491–2507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gong Z., Brackertz M., and Renkawitz R. (2006) SUMO modification enhances p66-mediated transcriptional repression of the Mi-2/NuRD complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 4519–4528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Allalou A., and Wählby C. (2009) BlobFinder, a tool for fluorescence microscopy image cytometry. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 94, 58–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Montalbano A. P., Hawgood S., and Mendelson C. R. (2013) Mice deficient in surfactant protein A (SP-A) and SP-D or in TLR2 manifest delayed parturition and decreased expression of inflammatory and contractile genes. Endocrinology 154, 483–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Liu X., and Fagotto F. (2011) A method to separate nuclear, cytosolic, and membrane-associated signaling molecules in cultured cells. Sci. Signal. 10.1126/scisignal.2002373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Trudgian D. C., and Mirzaei H. (2012) Cloud CPFP: a shotgun proteomics data analysis pipeline using cloud and high performance computing. J. Proteome. Res. 11, 6282–6290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Trudgian D. C., Thomas B., McGowan S. J., Kessler B. M., Salek M., and Acuto O. (2010) CPFP: a central proteomics facilities pipeline. Bioinformatics 26, 1131–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Craig R., and Beavis R. C. (2004) TANDEM: matching proteins with tandem mass spectra. Bioinformatics 20, 1466–1467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Geer L. Y., Markey S. P., Kowalak J. A., Wagner L., Xu M., Maynard D. M., Yang X., Shi W., and Bryant S. H. (2004) Open mass spectrometry search algorithm. J. Proteome Res. 3, 958–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Trudgian D. C., Ridlova G., Fischer R., Mackeen M. M., Ternette N., Acuto O., Kessler B. M., and Thomas B. (2011) Comparative evaluation of label-free SINQ normalized spectral index quantitation in the central proteomics facilities pipeline. Proteomics 11, 2790–2797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.