Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus mucocutaneous ulcer (EBVMCU) is a rare form of EBV lymphoproliferative disorder. The disease was recently described in 2010 for the first time in a case series and it was recently identified by the WHO classification of haematological malignancies as a separate category among the EBV lymphoproliferative disorders. We present a case of EBVMCU of the colon presenting as an ulcerating inflammatory mass in a female in her mid-60s who presented initially with abdominal pain and diarrhoea. The patient had extensive workup for her disease and due to progression of her symptoms, she was taken for an exploratory laparotomy. During the procedure, there was an inflammatory mass at the caecum and severe inflammation of the caecum and the terminal ileum and right hemicolectomy was performed. Diagnosis was confirmed by histopathology as EBV-positive lymphoproliferative disorder best classified as EBV-positive mucocutaneous ulcer.

Keywords: Gastroenterology, Pathology

Background

Epstein–Barr virus mucocutaneous ulcer (EBVMCU) is a rare form of EBV lymphoproliferative disorder which was recently recognised as a separate entity in 2010.1 Dojcinov et al described a case series of 26 patients with well-demarcated ulcers involving the skin, oral cavity, colon and rectum.1 The main risk factor for developing these ulcers is immunosuppression, including age-related immunosenescence.1 2

The diagnosis relies mainly on the histopathology and immunostaining to detect cluster of differentiation (CD)-30, CD-15 and EBV- encoded RNA (EBER).1 3

It is essential that physicians be aware of this new entity and differentiate it from other forms of EBV lymphoproliferative disorders since their therapeutic approaches are different. Since 2010, the disease has been reported in different case reports with different outcomes.3–5

Uncertainty surrounds the treatment options and the prognosis of this new disease due its rarity and the lack of randomised controlled trials to compare different treatment strategies.

Case presentation

A 64-year-old Caucasian female presented to the hospital after being referred by her gastroenterologist following a colonoscopy, which was done as part of workup of iron deficiency anaemia.

Initially, she presented to her gastroenterologist with the complaints of abdominal pain and intermittent diarrhoea of 1 year duration. The patient described colicky abdominal pain, poorly localised to the right side of the lower abdomen, which increased in intensity after meals. She reported losing 10 pounds over the past 6 months. The patient also endorsed feeling fatigue and tired easily with occasional shortness of breath on exertion. The patient had been seen by her primary care physician and she was diagnosed as having iron deficiency anaemia and she was started on oral iron replacement initially and later on she was switched to intravenous iron replacement. The patient was then scheduled for outpatient colonoscopy as part of workup of iron deficiency anaemia; following the procedure she developed severe abdominal pain and consequently she was referred to the hospital.

The patient had an extensive medical history which included coronary artery disease complicated by ischaemic cardiomyopathy and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, chronic atrial fibrillation treated with radiofrequency ablation and biventricular implantable cardiac defibrillator, hypothyroidism, partial seizures and depression. The patient was on anticoagulation with apixaban for her chronic atrial fibrillations, levetiracetam, carbamazepine, levothyroxine, sertraline, multivitamin and loperamide.

An abdominal examination revealed diffuse tenderness on palpation. A digital rectal examination did not show any masses but revealed a positive bedside faecal occult blood test.

Investigations

The patient’s laboratory investigations were significant for haemoglobin of 10.8 (Ref: 12–16 g/dL), mean corpuscular volume (MCV) 85 (Ref: 80–100 fL), mean corpuscular Hemoglobin (MCH) 27 (Ref: 26–34 pg). Stool was tested for Clostridium difficile toxins, Giardia, E. coli, Shigella, Salmonella and Cryptosporidium and none was detected.

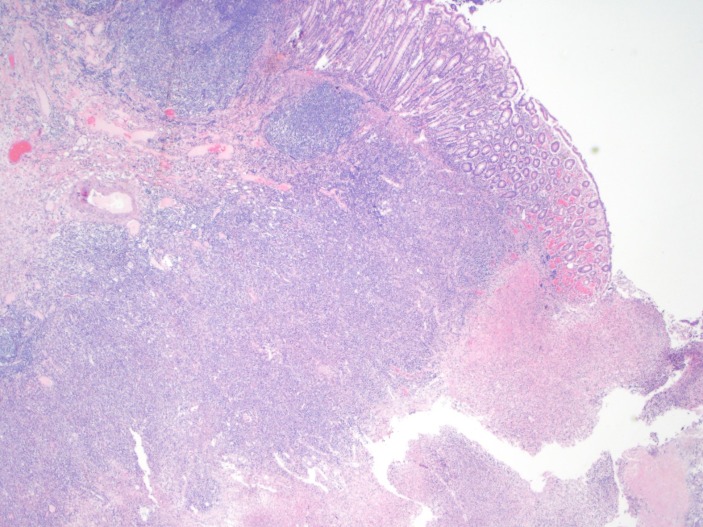

The colonoscopy, which was done prior to her referral to the hospital, showed a partially necrotic ulcer with surrounding colonic wall inflammation at the caecum and multiple biopsies were taken. Results of the biopsies came back as colonic mucosal fragments showing focal ulceration and features of inflammation (figure 1); however, there was no evidence of crypt distortion, crypt abscesses, granulomas or malignancy.

Figure 1.

Colonic mucosal fragments showing focal ulceration, focal acute cryptitis and infiltration by acute inflammatory cells in the lamina propria. (H&E original magnification ×100).

CT angiography (CTA) of the abdomen was done and showed wall thickening of the caecum and terminal ileum with mildly prominent mesenteric lymph nodes with patent celiac, superior and inferior mesenteric arteries.

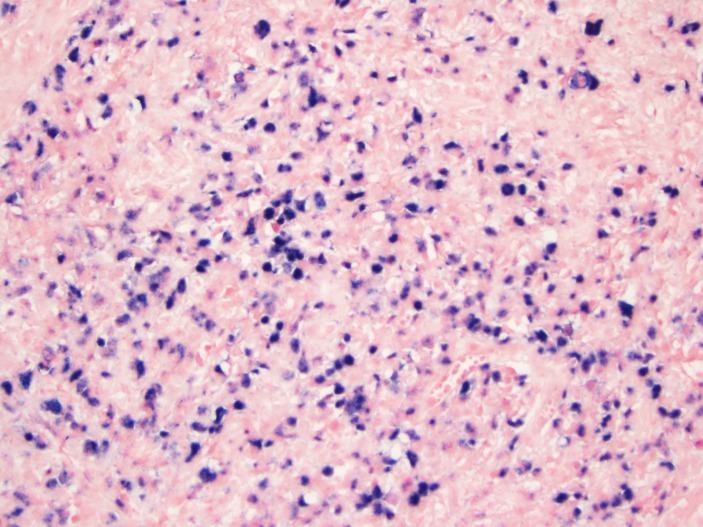

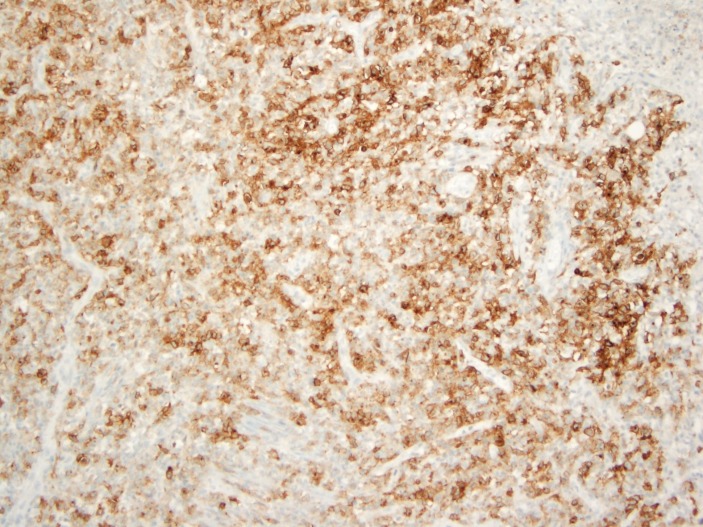

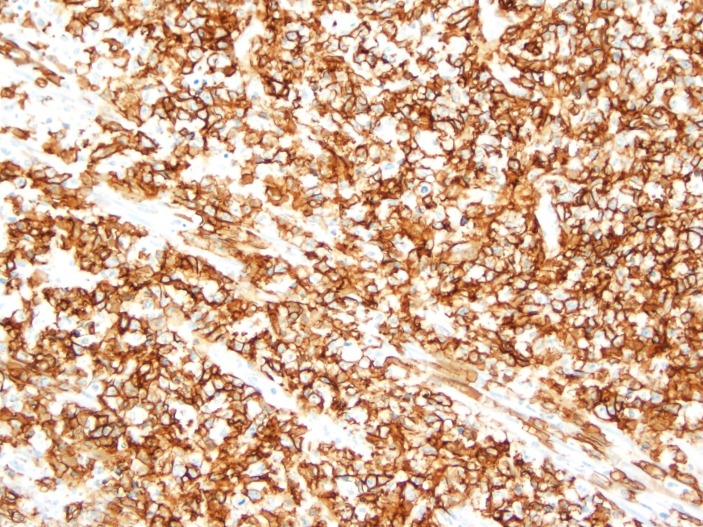

During the hospital stay and due to progression of her abdominal pain, the patient was taken to the operation room for an exploratory laparotomy. During the procedure, an inflammatory mass was seen at the caecum with redness and inflammation of the caecum and terminal ileum and consequently it was decided to proceed with right hemicolectomy. The results of the histopathology and special stains came as EBV-positive lymphoproliferative disorder best classified as EBVMCU, this was based on the immunostaining which tested positive for EBER (figure 2), CD-30 (figure 3) and CD-20 (figure 4). Mesenteric lymph nodes were reactive. Patient was referred to oncology service for bone marrow biopsy though she did not follow-up.

Figure 2.

In situ hybridisation for Epstein–Barr virus encoded RNA. (Original magnification ×200).

Figure 3.

Positive staining by CD-30 immunohistochemical stain. (Original magnification ×100).

Figure 4.

Positive staining by CD-20 immunohistochemical stain. (Original magnification ×200).

Differential diagnosis

The initial differential diagnosis was either chronic ischaemic colitis given the patient’s age and comorbidities or malignancy which was again supported by the patient’s age and the fact that she had iron deficiency anaemia. Other differential diagnosis includes infective colitis, ulcerative colitis, diffuse large cell lymphoma and other EBV lymphoproliferative disorders.

Treatment

The patient was initially treated with bowel rest; she was allowed to eat a liquid diet. She was also started on intravenous ciprofloxacin and metronidazole and she was given pain medications. Unfortunately, her abdominal pain intensified, so the patient was taken by the surgical team for an exploratory laparotomy.

During the surgery, there was an inflammatory mass at the caecum. The distal ileum had erythema, which involved the distal foot and half of the distal small bowel; however, the changes on the small bowel serosal surface were very subtle except for the ileocaecal valve, where the inflammatory mass was contained. The ascending colon appeared unremarkable beyond the mass, as did the transverse and the left colon also, which appeared unremarkable.

Given the findings described above, a decision was made to undergo right hemicolectomy with primary anastomosis.

The postoperative period was unremarkable with no complications and the patient’s symptoms improved. The patient was discharged home in stable medical conditions.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient’s symptoms improved after the surgery and the patient was discharged home. We followed up with the patient by phone calls and the patient was free from symptoms at 1 and 3 months follow-up. The patient was admitted to different institution about 6 months after her initial presentation with gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to anticoagulation as well as heart failure exacerbation. She passed away during that hospitalisation.

Discussion

EBVMCU is a rare form of extranodal lymphoproliferative disorder.2 6 The disease was initially recognised for the first time in 2010, in a case series which reported 26 cases of EBVMCU with overall similar clinical, pathological and prognostic features.1

The disease has been added to the lymphoid and haematopoietic tumour classification by the WHO and currently is classified as a separate category, previously it was part of diffuse large B cell lymphoma.7 8

According to the most recent systematic review, published in 2016, there are about 52 cases of EBVMCU reported in the literature; 52% reported in the oropharynx, 29% in the skin and 19% in the gastrointestinal tract.3

Immunosuppressed patients are at higher risk to get the disease, whether their immunosuppression is related to age-related immunosenescence (which affects innate and adaptive immunity), immunosuppressive therapy, chemotherapy, organ transplant or even stress-related transient immunosuppression.9–11

The disease presents as a superficial, sharply demarcated ulcer involving skin and mucous membranes.1 2 Reported cases described ulcers in the skin, oral mucosa, oesophagus, ileum and rectum.1 12 Although it is considered under the umbrella of lymphoproliferative disease, EBVMCU requires less immunosuppression to develop compared with malignant lymphoproliferative diseases and distinguishing between them is very important as the treatment will differ.12

The disease can create a diagnostic dilemma and confusion among physicians since it is a relatively new entity and can have a vague presentation when it affects the gastrointestinal tract. The diagnosis is usually based on the results of pathology, which typically show patchy necrosis, polymorphous infiltrate with large atypical transformed B cells which resemble Hodgkin’s/Reed–Sternberg-like cells that are CD-30 and CD-15 positive with variable CD-20, positive in situ hybridisation for EBER and a rim of reactive CD-3 positive T cells surrounding the base of the ulcer.1 9 13 Our patient histology slides showed a mixture of lymphocytes and immunoblasts. Immunostaining tested positive for EBER, CD-30 and CD-20 which favours the diagnosis.

EBVMCU in general has a waxing and waning course of illness and originally was believed to carry a good prognosis with resolution of the lesions on withdrawal of the offending immunosuppressive agent.1 4 Since its initial description in 2010, many case reports have been published with variable courses of illness.4–6

In the current era of uncertainty, the treatment approach for this relatively new entity remains a big challenge due to the lack of strong supportive evidence. In some case reports and case series, observation in conjunction with stopping the immunosuppressive therapy was sufficient for treatment of the EBVMCU,1 5 6 while some cases were treated with radiotherapy, chemotherapy or combination of both.1 4 6 In a case report by Magalhaes et al, an oral EBVMCU in a patient with diabetes was treated conservatively and a repeated biopsy after 2 months showed a healed ulcer; follow-up after a 12-month period showed that the patient remained free of recurrence.4 On the other hand, Moran et al described a case of EBVMCU of the colon in a patient with Crohn’s disease treated with infliximab and methotrexate, even after stopping the immunosuppressive agents the ulcer failed to regress and progressed to Hodgkin’s lymphoma after 18 months which shows the gloomy side of the EBVMCU.5

More researches are needed at the current time to guide the physicians to choose the correct treatment modality as well as to understand the prognosis of EBVMCU.

Learning points.

Physicians should be able to recognise EBVMCU as a new entity among EBV lymphoproliferative disorders.

The diagnosis of EBVMCU relies on the histopathology and immunophenotyping.

Immunosuppression is the main risk factor for EBVMCU and stopping the immunosuppressive agent is a crucial part of the treatment.

Footnotes

Contributors: MO, MAS and EAS took care of the patient in the hospital. MO and MAS wrote the manuscript. EAS reviewed the manuscript. SAH reviewed the case, edited it and reviewed the related literature.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Dojcinov SD, Venkataraman G, Raffeld M, et al. EBV positive mucocutaneous ulcer – a study of 26 cases associated with various sources of immunosuppression. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:405–17. 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181cf8622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dojcinov SD, Venkataraman G, Pittaluga S, et al. Age-related EBV-associated lymphoproliferative disorders in the Western population : a spectrum of reactive lymphoid hyperplasia and lymphoma age-related EBV-associated lymphoproliferative disorders in the Western population : a spectrum of reactive lymph. Blood 2012;117:4726–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts TK, Chen X, Liao JJ. Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges of EBV-positive mucocutaneous ulcer: a case report and systematic review of the literature. Exp Hematol Oncol 2015;5:13 10.1186/s40164-016-0042-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magalhaes M, Ghorab Z, Morneault J, et al. Age-related Epstein-Barr virus-positive mucocutaneous ulcer: a case report. Clin Case Rep 2015;3:531–4. 10.1002/ccr3.287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moran NR, Webster B, Lee KM, et al. Epstein Barr virus-positive mucocutaneous ulcer of the colon associated Hodgkin lymphoma in Crohn's disease. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:6072–6. 10.3748/wjg.v21.i19.6072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ok CY, Papathomas TG, Medeiros LJ, et al. EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly. Blood 2013;122:328–40. 10.1182/blood-2013-03-489708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asano N, Yamamoto K, Tamaru J, et al. Age-related Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: comparison with EBV-positive classic Hodgkin lymphoma in elderly patients. Blood 2009;113:2629–36. 10.1182/blood-2008-06-164806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The updated WHO classification of hematological malignancies. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood 2016;127:2375–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hart M, Thakral B, Yohe S, et al. EBV-positive mucocutaneous ulcer in organ transplant recipients: a localized indolent posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder. Am J Surg Pathol 2014;38:1522–9. 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ling PD, Lednicky JA, Keitel WA, et al. The dynamics of herpesvirus and polyomavirus reactivation and shedding in healthy adults: a 14-month longitudinal study. J Infect Dis 2003;187:1571–80. 10.1086/374739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aw D, Silva AB, Palmer DB. Immunosenescence: emerging challenges for an ageing population. Immunology 2007;120:435–46. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02555.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen B-J, Fang C-L, Chuang S-S. Epstein-Barr virus-positive mucocutaneous ulcer. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2016:2–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swerdlow SH, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Willemze R, et al. Cutaneous B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: report of the 2011 Society for Hematopathology/European Association for haematopathology workshop. Am J Clin Pathol 2013;139:515–35. 10.1309/AJCPNLC9NC9WTQYY [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]