Abstract

Background

As more is understood regarding the human microbiome, it is increasingly important for nurse scientists and health care practitioners to analyze these microbial communities and their role in health and disease.16S rRNA sequencing is a key methodology in identifying these bacterial populations that has recently transitioned from use primarily in research to having increased utility in clinical settings.

Objectives

The objectives of this review are to: (a) describe 16S rRNA sequencing and its role in answering research questions important to nursing science; (b) provide an overview of the oral, lung and gut microbiomes and relevant research; and (c) identify future implications for microbiome research and 16S sequencing in translational nursing science.

Discussion

Sequencing using the 16S rRNA gene has revolutionized research and allowed scientists to easily and reliably characterize complex bacterial communities. This type of research has recently entered the clinical setting, one of the best examples involving the use of 16S sequencing to identify resistant pathogens, thereby improving the accuracy of bacterial identification in infection control. Clinical microbiota research and related requisite methods are of particular relevance to nurse scientists—individuals uniquely positioned to utilize these techniques in future studies in clinical settings.

Keywords: 16S rRNA sequencing, human microbiome, nursing research, translational research

Research on the human microbiome, once a fairly unknown field, has grown exponentially in the past decade. Human beings are now known to be born with certain bacteria, archaea, and viruses that live as symbionts. All humans are “colonized” at birth and further develop and perturb the microbiome in response to different environmental factors and stimuli. These bacteria also serve important roles in human processes; for example, some bacteria in the human microbiome benefit their human host by assisting in digesting complex molecules (den Besten et al., 2013). Not all bacterial inhabitants are beneficial, however: disease-causing pathogens can proliferate in the microbiome, potentially leading to life-threatening conditions such as metabolic endotoxemia (Patterson et al., 2016). Understanding the many trillion bacterial inhabitants of the human microbiome and how they interact with their host is essential, not only from a research viewpoint, but also from a clinical perspective. Using the 16S rRNA gene to identify bacteria in these multiple biomes is the first step.

In 2008, with the start of the Human Microbiome Project (HMP), a National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded collaboration aimed at characterizing the healthy microbiome, scientists have begun to understand some of the characteristics of core, healthy microbiomes (Huse, Ye, Zhou, & Fodor, 2012; Human Microbiome Consortium, 2012b). Less is known, however, about the dynamic changes that occur in the microbiome, the importance and magnitude of which is becoming clearer as the microbiome has been identified in a multitude of body sites and implicated in an ever-increasing number of diseases (Blaser, 2014). Better characterized microbiomes such as the oral, skin, and gut have evolving implications in health and disease (Clemente, Ursell, Parfrey, & Knight, 2012; Schloss, 2014; Xu et al., 2015). But biomes such as the lung, and vaginal microbiomes are emerging as important clinical research targets (Beck, Young, & Huffnagle, 2012; Ravel et al., 2011). Many diseases and conditions have been correlated with microbiome dysbiosis, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Mammen & Sethi, 2016), inflammatory bowel disease (Bakhtiar et al., 2013), dermatitis and other atopic diseases (Grice et al., 2008), as well as bacterial vaginosis and stillbirth (Han et al., 2010; Ravel et al., 2011).

This paper will provide an overview of the importance of the human microbiome in health and disease and outline a key methodology to interpret these complex communities. Developing an understanding of the microbiome and the methods used to describe it is particularly relevant to nurse scientists. Although many other disciplines merge bench science with symptom science, nurse scientists are uniquely positioned to contribute to the growing translational science of the microbiome because of their strong research history in symptomology. The significance of 16S sequencing in answering research questions important to nursing science will be illustrated by first presenting a review of three clinically relevant microbiomes—the oral, lung and gut microbiomes. Then, the human microbiome will be explored in the clinical environment, with particular emphasis on the use of 16S rRNA microbiome sequencing in tracking outbreaks of resistant bacteria. Finally, limitations to advancing current microbiome research will be broadly considered.

Background

Table 1 lists useful websites with information about current research on the human microbiome.

TABLE 1.

Useful Websites About Microbiome Research

| Host | URL |

|---|---|

| University of Maryland Institute for Genome Science | http://www.igs.umaryland.edu |

| University of Chicago The Microbiome Centera | https://microbiome.uchicago.edu |

| NIH Human Microbiome Project Microbial Reference Genomes | http://www.hmpdacc.org/reference_genomes/reference_genomes.php |

| NIH Human Microbiome Project dbGaP Genotypes and Phenotypes | www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/study.cgi?study_id=phs000228.v3.p1 |

| American Gut Project | http://americangut.org/ |

Note. NIH = National Institutes of Health.

In collaboration with Argonne National Laboratory, Lemont, IL and Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, MA.

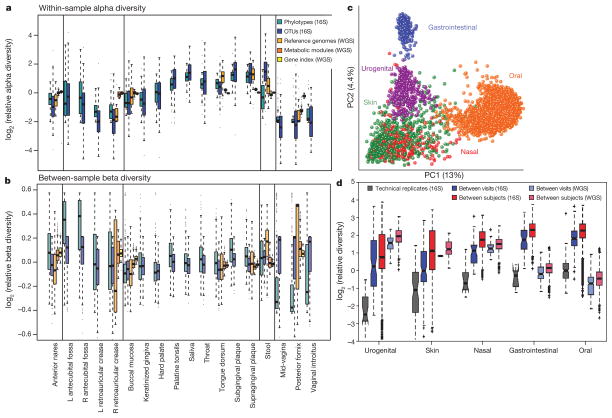

The Healthy Microbiome

In order to understand the role of the microbiome in disease, scientists must have a baseline from which to compare. Fortunately, the HMP has undertaken an unprecedented categorization of the healthy human microbiome of several different body sites through 16S sequencing of multiple variable regions (Human Microbiome Project Consortium, 2012a, 2012b). The goal of the HMP was to sequence 3,000 genomes from both cultured and uncultured bacteria (http://www.hmpdacc.org/reference_genomes/reference_genomes.php), contributing not only to the understanding of the healthy biome, but also assembling the largest reference database for future comparison and classification (Jumpstart Consortium HMP Working Group, 2012). Samples were collected from 242 adults resulting in 5,177 taxonomically characterized communities comprising the airway, skin, oral, gut, and vaginal biomes (Human Microbiome Consortium, 2012a). One hundred and thirty-one individuals were sampled at an additional time point in order to examine longitudinal changes. Results were characterized by the number and abundance of each organism in order to describe overall diversity. Oral and stool communities were the most diverse, while vaginal communities showed the lowest diversity (Human Microbiome Project Consortium, 2012b). Diversity was further classified into alpha and beta, with alpha representing the diversity of organisms within each site and beta describing the differences in species composition between subjects. For example, saliva had high alpha diversity and a number of unique organisms, but when examining the beta diversity across individuals, the overall oral microbiome was similar, resulting in a low-beta diversity. The skin microbiome had the highest beta diversity and lower alpha diversity, logically depicting the susceptibility of this microbiome to environmental perturbations. In general, changes in the human microbiome within subjects over time was much smaller than the intersubject variability, implying that the microbiome is relatively stable over time, yet unique to each individual (Human Microbiome Project Consortium, 2012b). Communities were affected by outside factors such as oxygen, moisture, pH, host immunology, and microbial interactions (Human Microbiome Project Consortium, 2012b). With the wealth of data characterizing the healthy microbiome now available as a result of the HMP, researchers must seek to further understand the complexities of the human microbiome and delve deeply into functional metabolomics of these bacteria to advance knowledge of their role in health and disease.

16S rRNA and Next-Generation Sequencing to Characterize the Human Microbiome

Historically, identification of bacteria relied solely upon culture methods that often failed to identify certain bacteria that do not grow in common media (Srinivasan et al., 2015). This method of bacterial identification is especially challenging when examining a community of organisms with different individual growth characteristics. Many organisms resist growth in culture like Burkholderia spp. and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Srinivasan et al., 2015).

The 16S rRNA sequencing method has allowed for a simple and effective alternative to microbial culture. The 16S rRNA gene codes for a ribosomal subunit that is widely conserved among bacteria and contains hypervariable regions interspersed among conserved regions of its sequence (Clarridge, 2004). These hypervariable regions are unique to each bacterial species, allowing for classification or taxonomy. The conserved regions, on the other hand, allow for the development of universal primers that bind to known sequences shared among most bacteria. Short read sequencing of approximately 200–400 base pairs is capable of targeting one or several proximal regions through the use of specific primers that align to the conserved regions on either side of the hypervariable target (Ghyselinck, Pfeiffer, Heylen, Sessitsch, & De Vos, 2013). Of the nine hypervariable regions, some regions better characterize bacteria and the choice of which region, and therefore the appropriate primers to use, is an important step in study design (Ghyselinck et al., 2013; Mizrahi-Man, Davenport, & Gilad, 2013). For example, the V1-V3 region is preferred by some in studies examining the oral microbiome (Zheng et al., 2015). This issue of selection of the hypervariable regions is by no means straightforward and remains controversial. Some scientists believe that sequencing multiple variable regions is the best option, providing a nonbiased, comprehensive view of these complex microbiomes (Barb et al., 2016).

Before next generation sequencing, most research characterizing bacterial communities utilized Sanger sequencing, which allowed for longer reads—often greater than 500 base pairs (Vincent, Derome, Boyle, Culley, & Charette, in press). However, the increased speed, reduced cost, simpler protocols, and comparable read lengths of next-generation sequencers have allowed them to virtually replace Sanger sequencing (Rhoads & Au, 2015). Regardless of sequencing method, final results are represented in operational taxonomic units (OTUs), which is a sequence identifying an organism usually at the genus or species level (Dickson et al., 2016).

One of the major constraints in all microbiome studies is the complexity and amount of data that is obtained (Dudhagara et al., 2015). These “big datasets” require a careful bioinformatics plan for analysis in order to provide clear, concise results capable of furthering scientific discovery in this rapidly changing field. The nurse scientist requires collaboration with experienced bioinformaticists who understand the issues and complexity involved in theses analyses. Scientists may also collaborate with a microbiome research center; examples are the University of Maryland’s Institute for Genome Science (http://www.igs.umaryland.edu/) and the University of Chicago’s Microbiome Center, which coordinates with Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, Illinois and Marine Microbiological Labs at Woods Hole, Massachusetts (https://microbiome.uchicago.edu/).

Selected Microbiomes

In this section, microbiomes of particular interest to researchers are reviewed. Detailed information about studies cited is available (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1).

The Oral Microbiome

The mouth contains many different structures and tissues, each of which hosts a characteristic biotic community. However, in the HMP data, a comparison of the tongue and saliva specimens reveals that they share similar genera (Human Microbiome Project Consortium, 2012b). The type and abundance of organisms in the plaque microbiota vary greatly between samples collected above the gum line (supragingival) or below (subgingival) (Segata et al., 2012). Additionally, saliva bathes the entire cavity, continuously introducing some of its bacteria into other oral samples. More specifically, saliva represents an example of a microbiome with high alpha but low beta diversity (Human Microbiome Project Consortium, 2012b). These distinct environments present multiple challenges to researchers, as all sites are dynamic, microbial communities constantly changing over time in response to different stimuli and diseases. It is difficult to know how to compare the different regions, and it is even more difficult to decide which region, if any, is representative of the entire oral microbiome. In the HMP, nine sites from the oral cavity were sampled from healthy volunteers: the saliva, tongue dorsum, hard palate, buccal mucosa, keratinized gingiva or gums, palatine tonsils, throat and supra- and subgingival plaque (Human Microbiome Project Consortium, 2012b). The results demonstrated that the alpha diversity was influenced by body habitat as all oral samples grouped together in a principal components analysis (Figure 1; Human Microbiome Project Consortium, 2012b.). HMP participants were healthy volunteers who met about 35 major exclusion criteria, including some directly relevant to the oral microbiome: periodontal disease, more than eight missing teeth, halitosis and untreated cavitated carious lesions or oral abscesses (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/study.cgi?study_id=phs000228.v3.p1). Therefore, assumptions cannot be made about diversity among participants with good oral hygiene, for example.

FIGURE 1.

Principal components analysis of samples from the Human Microbiome Project revealing variation by body site, as skin, urogenital, gastrointestinal, nasal and oral microbiome each cluster separately. From the Human Microbiome Project Consortium (2012b). Used with permission.

Core oral microbiome

Based on molecular methods, it is not clear whether a “core oral microbiome” exists (Zaura, Keijser, Huse, & Crielaard, 2009), which is a concept redefining the diversity of the oral microbiome. Keijser et al. (2008) identified 3,621 species-level phylotypes (DNA sequences that are compared to a database) in saliva and over 6,888 in plaque. This estimate of diversity in the oral microbiome is much greater than previously reported. K. Li, Bihan, & Methé (2013) studied the HMP database and identified a relatively small and stable core oral microbiome in all nine oral sites. In addition, this study examined a minor core microbiome where bacteria were in low abundance, but present in the majority of the samples. For example, the tongue dorsum revealed three important taxa: Actinomycetales unclassified, Bacilli unclassified, and Peptostreptococcaceae peptostreptococcus (K. Li et al., 2013). Identification of these low abundance microorganisms provided support for the hypothesis of a “minor core oral microbiome” (K. Li et al., 2013). Future studies may benefit from knowledge about the presence or absence of these organisms.

The oral microbiome and pneumonia

In the clinical setting, interest in the oral cavity began with publication of papers linking plaque biofilm, sampled from patients receiving care in medical ICUs and elderly living in institutions, with pathogens later associated with nosocomial infections (El-Solh et al., 2004; Fourrier, Duvivier, Boutigny, Roussel-Delvallez, & Chopin, 1998; Heo, Haase, Lesse, Gill, & Scannapieco, 2008; Scannapieco, Stewart, & Mylotte, 1992). Results showed an important association between pathogens identified in the mouth and bacteria in the lung. The proposed pathogenic theory included aspiration of pathogen-contaminated saliva trafficked to the lungs where pneumonia developed. The saliva-to-lung hypothesis became the driving force behind randomized control trials in critical care to examine whether oral decontamination would decrease pneumonias in intubated, critically ill patients (Bergmans et al., 2001; Houston et al., 2002; DeRiso, Ladowski, Dillon, Justice, & Peterson, 1996; Segers, Speekenbrink, Ubbink, van Ogtrop, & de Mol, 2006). Three out of four studies used chlorhexidine oral rinses in a cardiac surgery population (DeRiso et al., 1996; Houston et al., 2002; Segers et al., 2006) and one (Bergmans et al., 2001) used a combination of topical antibiotics applied to the oral cavity. The Bergmans et al. (2001) study was performed in three critical care units in the Netherlands in a mixed critical care population. Segers et al. (2006) used chlorhexidine rinses and chlorhexidine ointment in the nasal passages. All four studies demonstrated effectiveness: decrease in nosocomial infections in the treatment group (DeRiso et al., 1996; Segers et al., 2006), decrease in nosocomial pneumonia in a subgroup of patients intubated longer than 24 hours (Houston et al., 2002), and decrease in ventilator-associated pneumonia in the treatment group (Bergmans et al., 2001). Findings from these studies and a recent meta-analysis (Hua et al., 2016) provide strong evidence to support the use of oral hygiene care that includes chlorhexidine mouthwashes or gel in decreasing the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). The Institute for Healthcare Improvement developed other strategies to decrease the risk of VAP and called these strategies that included among others a “sedation vacation” and peptic ulcer prophylaxis, the VAP Bundle (Resar et al., 2005). A recent study provides an extensive cost-benefits analysis of the traditional VAP Bundle and other methods to prevent VAP (Branch-Elliman, Wright, & Howell (2015).

Oral–gut microbiome connection

The oral and gut microbiomes may be linked. Using the HMP database, Ding and Schloss (2014) found that the oral and gut microbiomes were predictive of each other, despite differences in the microbiota; they speculated that, although the gut and oral microbiome have different members, the “oral bacterial populations seed the gut” (p. 358). Dysbiosis in the salivary microbiome of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (Crohn’s disease n = 21; ulcerative colitis n = 14) when compared to healthy controls (n = 24) provides additional information about an oral–gut link (Said et al., 2014); the dysbiosis was characterized by a significant increase in Prevotella and Veillonella and a decrease in two other genera, Streptococcus and Haemophilus in IBD patients compared to healthy controls (Said et al., 2014). This finding could be important in future studies of the gut and oral microbiomes, potentially helping to define both. This connection could also have important clinical implications. For example, if this change in the oral microbiome communities was consistent across populations and predictive of IBD, a simple, salivary sample could be used for diagnosis. Future studies examining the predictive ability of salivary biomarkers are needed.

Lung Microbiome

Until recently, infectious disease texts have described the lung as sterile (Mandell, Bennett, & Dolin, 2010), a fact now known to be incorrect. Pulmonologists and microbiologists held the “sterile hypothesis” due to an inability to identify bacteria using conventional culture methods in normal, healthy individuals. A large percentage of the bacteria that compose the oral and lung microbiomes are unculturable or difficult to grow in the clinical laboratory (Bahrani-Mougeot et al., 2007). In addition, sampling of the lower respiratory tract is difficult, invasive, and requires a skilled bronchoscopist in order to obtain samples safely. Identification of members of the lung microbiome has advanced with 16S rRNA sequencing, resulting in a much more detailed understanding of the microbial makeup of the lung biome (Dickson, Erb-Downward, Martinez, & Huffnagle, 2016).

One of the first studies suggesting an association between bacteria and inflammation in the lung was performed to test this relationship in mice (Herbst et al., 2011). Although this study did not use sequencing it provided evidence of a connection. Germ-free mice were found to have airway hyperactivity and alteration in certain immune cell lines compared to controls when stimulated with ovalbumin—a protein and immune stimulant, a process that was reversed when the germ free mice were colonized with the commensal bacteria from the controls. In another study, 16S rRNA was used to identify bacteria from airway microbiota obtained through bronchial lavages and protective specimen brushings in three groups: asthmatics (n = 11), patients with chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD) (n = 5), and healthy controls (n = 8) (Hilty et al., 2010). Not only were none of the airways sterile, the microbiota of patients with asthma or COPD was described as “disturbed.” Despite the small sample size, prior thinking was challenged and the concept of the sterile bronchial tree and lung added to the evidence that disease states and dysbiosis of the microbiome were somehow related. A subsequent study by Charlson et al. (2012) collected samples from multiple upper airway sites in six normal volunteers with “potential heavy lung colonization” and compared oral and lung samples. This study and others provided strong support that the lung has a unique microbiome (Charlson et al., 2011; Dickson et al., 2014; Morris et al., 2013).

Historically, microbiome studies have been limited by small sample size. This is especially true in the lung microbiome studies, perhaps because of the invasive nature of the sampling. However, accumulation of data in large, public-access reference databases may correct this limitation (McDonald, Birmingham, & Knight, 2015).

Recently, researchers have begun to investigate the relationship between the gut and lung microbiomes. A study performed in mice infected with Streptococcus pneumoniae found that intact intestinal microbiota conferred pathogenic protection when compared to mice that had their gut microbiota depleted (Schuijt et al., 2016). The alveolar macrophages of the mice with depleted gut microbiomes had decreased ability to engulf and destroy bacteria (Schuijt et al., 2016). Like the germ-free mice studied by Herbst et al. (2011) that were less likely to respond appropriately to airway inflammation than mice with a normal microbiome, the gut–lung axis demonstrated in this study highlights that communication between two different microbiomes may play an important role in disease protection. A recent review highlights this complexity by relating the dysbiosis of the gut to the lung microbiome and the impact of chronic lung disease (O’Dwyer, Dickinson & Moore, 2016).

Gut Microbiome

The gut microbiome is one of the most studied biomes and has been shown to contain the greatest number of organisms, the vast majority of which are located in the colon (Sender, Fuchs, & Milo, 2016). The number of bacteria in the gut microbiome has been estimated to range from 1013 to 1014 organisms (about 100 trillion) (Gill et al., 2006). (Recently, the number of bacteria in the entire body was estimated to be about 3.9 × 1013; Sender et al., 2016). No matter what the final number of bacteria is estimated to be, it is undisputed that the vast majority of the gut bacteria belong to two major bacterial phyla: Bacteriodetes and Firmicutes (Mahowald et al., 2009).

The gut microbiota serve an important role in the gastrointestinal system by breaking down short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) (Krajmalnik-Brown, Ilhan, Kang, & DiBaise, 2012). Disruption of the normal bacterial community (gut dysbiosis) has been implicated in irritable bowel syndrome (Kennedy, Cryan, Dinan, & Clarke, 2014), inflammatory bowel disease (Rehman et al., 2016) and gastrointestinal malignancy (Abreu & Peek, 2014). Human and animal studies have also directly linked changes in the gut microbiota to obesity (Graessler et al., 2013; Kasai et al., 2015; Ridaura et al., 2013; Turnbaugh et al., 2009). Antibiotics have been shown to create gut dysbiosis by disrupting the balance of the microbiota (Modi, Collins, & Relman, 2014), a change that can be lasting. For example, macrolide antibiotics changed the gut microbiome for up to two years when fecal samples of 142 children were studied (Korpela et al., 2016). Antibiotic use also has been implicated in changes in gut microbiota and weight gain, especially in children (Saari, Virta, Sankilampi, Dunkel, & Saxen, 2015; Scott et al., 2016). Antibiotic exposure, bacterial resistance genes and the gut microbiome represent a complex area of research that requires further study (Halpin et al., 2016; Raymond et al., 2016)

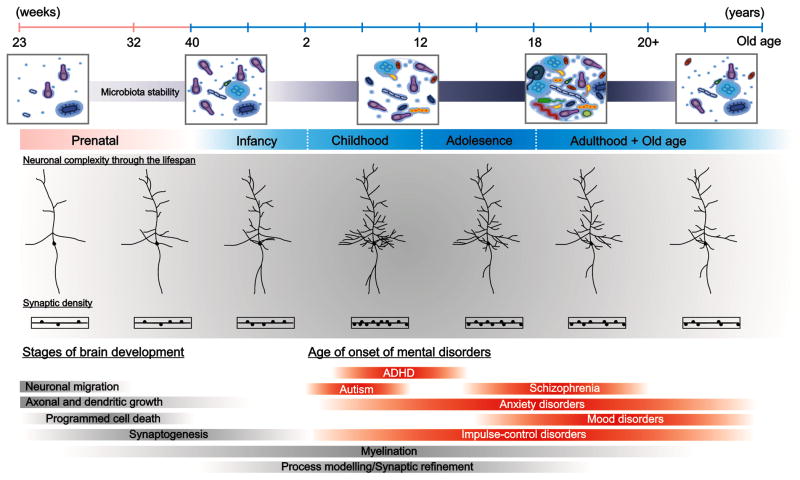

Gut microbiome across the lifespan

Figure 2 represents a graph of important microbiome changes over time (Borre et al., 2014). The gut microbiome is formed early in life and is influenced at birth by many factors, including maternal health (Mueller, Bakacs, Combellick, Grigoryan, & Dominguez-Bello, 2015). Gut microbiome varies distinctly as a function of vaginal or Cesarean section (C-section) delivery (Rutayisire, Huang, Liu, & Tao, 2016). The skin bacteria of infants were associated with maternal vaginal microbiomes, whereas that of the C-section babies were composed of skin bacteria (Dominguez-Bello et al., 2010). The implications of these findings could be most important for infant health, as the percentage of C-section births is approximately 32% (Hamilton, Martin, Osterman, Curtin, & Matthews, 2015, p. 7) and babies born by C-section may have delayed establishment of their microbiomes (Dominguez-Bello, Blaser, Ley, & Knight, 2011). As the child matures, the microbiome gradually becomes more diverse (Borre et al., 2014), a trend that is reversed in older age when diversity decreases and a change in certain taxa occurs (Jackson et al., 2016). Fecal specimens from 13 young adults and 178 Caucasian, elderly individuals (64 to 102 years) showed that the gut microbiota changed with location of the elderly resident (assisted living, day-hospital, rehabilitation, long-term care or community) and diversity of the diet (Claesson et al., 2012); differences in the gut microbiome with diet, as well as with health outcomes such as increased fragility (significantly correlated), blood pressure and geriatric depression.

FIGURE 2.

Dynamic changes in the microbiome throughout life as communication takes place between the central nervous system and the gastrointestinal tract. As development occurs, microbiome stability changes and during infancy, adolescence and old age may contribute to development of mental health disorders. ADHD = attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. From Borre et al. (2014). Used with permission.

Brain–gut microbiome interaction

One of the most interesting and potentially productive areas for future gut microbiome research is the connection between the gut microbiome and the brain. Information about significant gut-brain research studies and their major outcome measures is tabled in Supplemental Digital Content 2 and discussed below.

There is direct communication between the gut microbiome and the brain, and many believe this communication occurs reciprocally (Bauer, Huus, & Finlay, 2016; Carabotti, Scirocco, Maselli, & Severi, 2015; Kelly, Clarke, Cryan, & Dinan, 2016; Q. Li & Zhou, 2016). Mouse studies have examined this interaction (Clarke et al., 2013; Davari, Talaei, Alaei, & Salami, 2013; Desbonnet et al., 2015; Diaz Heijtz et al., 2011; Tsurugizawa et al., 2009). The microbiome gut–brain axis has been directly linked to anxiety (Clarke et al., 2013), depression (Claesson et al., 2012), autism (Finegold et al., 2010), and Alzheimer’s disease (Bhattacharjee & Lukiw, 2013).

The immune (Erny et al., 2015) and endocrine systems (El Aidy, Dinan, & Cryan, 2015) may also be affected by the gut microbiome. These fascinating gut-brain connections are being examined; however, the complexity and state of early phase research limits a detailed review at this time. Evidence to support the interaction between gut microbes, the immune system, the neuroendocrine system, and the “psychoneuroimmunology network” is summarized in El Aidy et al. (2016). An example of this interaction is the role of the chronic stress predisposing humans to increased gut permeability and translocation of bacteria from the gut lumen into the circulation; some evidence suggests that probiotics can reverse this trend (Liu, Jiang, Zhou, Song, & Zhang, 2016).

Difficulties in gut microbiota sample processing and storage

Challenges involving specimen collection, processing, and storage are particularly pertinent to gut microbiome investigations, as most microorganisms reside in the gastrointestinal tract and fecal microbiome composition undergoes marked change over time, which complicates specimen storage and sampling protocols (Song et al., 2016). Effective sampling methods are needed to advance understanding of the gut microbiome (Gorzelak et al., 2015). However, no consensus exists regarding either standard sample collection and processing practices or sequencing protocols and storage methods are rarely sufficiently addressed in manuscripts (Thomas, Clark, & Doré, 2015), presenting significant obstacles for ongoing research. Gorzelak et al. (2015) proposed freezing feces within 15 minutes of defecation, storing specimens in a frost-free freezer for up to three days and homogenizing stool to reduce microbiome variability across sampled microenvironments. However, other storage recommendations include immediate freezing of samples at -80 °C, storage at 4 ° C followed by freezing at -80 °C or addition of a stabilization agent (Thomas et al., 2015). Still, others maintain that variations in short-term storage conditions do not alter bacterial community composition significantly (Lauber, Zhou, Gordon, Knight, & Fierer, 2010). The choice of stabilization reagent is another challenge for researchers utilizing “omics” methods, as these procedures often necessitate the simultaneous preservation of DNA, RNA, and other metabolites, thereby preventing the use of an agent optimized for a single molecule (Song et al., 2016). Certainly, the literature presents a plethora of sample storage and processing options for the researcher, underscoring the need for standardized and optimized protocols for cross-study comparison (Gorzelak et al, 2015; Thomas et al., 2015).

Clinical Applications

Hospital-Acquired Infections and 16S rRNA Identification of Bacteria

Hospital-acquired infections are an increasingly important issue in clinical microbiology and epidemiology. Accurate tracking and identification of pathogens, particularly those resistant to antibiotics, is of utmost importance (Punina, Makridakis, Remnev, & Topunov, 2015). Currently, culture methods are usually employed to identify the responsible pathogen and broad-spectrum antibiotics are utilized during the period prior to identification of causative pathogens (Lax & Gilbert, 2015). Identification of the pathogen is fundamental for proper antibiotic stewardship. Use of 16S rRNA sequencing is a feasible, emerging tool for clinical microbiology laboratories to accelerate pathogen identification and identify bacteria that otherwise could not otherwise be successfully cultured. Using 16S rRNA to assess the entire bacterial community allows for the analysis of hospital surfaces and equipment that often harbor pathogens, informing hospital cleaning regimens and epidemiology practices to reduce the spread of infection.

Use of 16S rRNA sequencing is particularly useful in situations where a patient’s specimen may contain hundreds of organisms, as traditional culture techniques may fail to isolate the organism of interest. Furthermore, 16S sequencing allows characterization of the complete bacterial community for an informed treatment decision. The 16S sequencing approach can be used to characterize bacterial communities that are typically hard to identify (Bharadwaj et al., 2012). For example, Bharadwaj et al. (2012) examined the effect of 16S sequencing on treatment outcomes in a clinical setting over a four-year period in 172 patients. These 172 patients had bacteria that were difficult to identify by standard clinical laboratory methods. In 140 patients, the organism identified did not change clinical management. However, in 24 patients with mycobacteria or other gram-positive bacilli with retrievable, clinical information, the additional information gained from the 16S sequencing led to treatment modification, initiation or discontinuation in 14 patients. Early hospital discharge was facilitated in many instances. Importantly, all 14 patients with treatment changes were alive 30 days postinfection, suggesting that using 16S sequencing to guide treatment potentially may save lives. Of the remaining 10 patients, six received appropriate therapy before the results of the molecular tests were available, two patients died and two left against medical advice (Bharadwaj et al., 2012).

Another clinical example involved a pipeline tested on samples from cystic fibrosis patients; it was especially useful for low-prevalence or hard to identify bacteria (Salipante et al., 2013). Additionally, 16S methodology was much faster and more cost effective for detailed analysis than traditional methods, producing results within one day.

Toma et al. (2014) used novel next-generation sequencing in mechanical ventilator patients, subjecting 44 tracheal aspirate samples to Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT, Pacific Biosciences of California, Inc.) long-read 16S sequencing that uses approximately 95% of the 16S rRNA gene instead of merely one or two hypervariable regions. The authors in this study identified clinically important genera that were not identified in the clinical culture results (Toma et al., 2014).

In a review examining the microbiota as a target for infection control interventions, researchers outline emerging methods that harness the microbiome to combat antibiotic-resistant infections (Pettigrew, Johnson, & Harris, 2016). Proposed solutions include the introduction of commensals, or probiotics, to help patients maintain a healthy microbial community less susceptible to overgrowth and antibiotic resistant infection. At present, studies have produced mixed results and more research is necessary to understand the efficacy of probiotic administration for infection prevention.

16S rRNA and Bacterial Sensitivities

Although 16s rRNA sequencing has enlarged understanding of the human microbiome, taxonomic resolution is a limitation, as often the lowest classification possible is at the genus level. This is not as informative or powerful for identification of species- or strain-specific pathogens. Additionally, antibiotic sensitivities cannot be ascertained, making this an area where culture methods remain necessary. Whole genome sequencing is gaining traction over 16S sequencing, as improved resolution and strain-level mutations can inform antibiotic resistance. Researchers at the NIH Clinical Center used whole genome sequencing to track a carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae outbreak (Snitkin et al., 2012), demonstrating its utility in hospital epidemiology through the identification of the specific transmission route. In the clinical microbiological setting, whole genome sequencing for isolate characterization remains limited, primarily due to increased cost, time, education and training of staff (Kwong, McCallum, Sintchenko, & Howden, 2015). User-friendly bioinformatics pipelines are under development and represent a critical next step towards universal adoption of whole genome sequencing in clinical microbiology and epidemiology.

Clinical Implications and Future Directions for Nurse Scientists

Table 2 highlights nursing research questions related to the oral, lung and gut microbiome discussed below.

TABLE 2.

Microbiome Questions for Nursing Research

| Microbiome | Priority questions for nursing research |

|---|---|

| Oral |

|

| Lung |

|

| Gut |

|

Oral Microbiome

The oral microbiome is a rich area for multidisciplinary studies between nurse scientists, dentists, and others interested in this complex environment. Because of nursing’s role in direct patient care, from routine assessment to providing oral care and patient education, nurse scientists are especially well-positioned to design studies examining this important biome in special populations (Ames et al., 2012). Research is relatively more feasible because the oral cavity is accessible. Nurse scientists designing oral microbiome studies must think carefully, however, about which site or sites in the oral cavity they should sample. Sites selected should be based upon the populations of interest and the aims of the study, but training and ease of collection should also be considered. Development of an antimicrobial peptide that that specifically targets Streptococcus mutans, a major cause of caries, illustrates the translational nature of oral microbiome research (Guo et al., 2015). Similar manipulations may have a role in the future treatment for disease and are important areas for nurse scientists to address.

Lung Microbiome

There are many opportunities for clinical studies examining the lung microbiome in healthy individuals and individuals with diseases such as pneumonia and asthma. This is especially true with regards to the challenges in obtaining samples. There is a procedure for bronchoscopy to prevent or decrease contamination from oral specimens (Charlson et al., 2012), but bronchoscopy is still not without risk—making justification for its use in research with healthy individuals somewhat problematic. Careful attention to study design and outcomes is essential. Research examining less invasive routes of effectively sampling the lung microbiome would be especially useful, as would larger studies examining associations between the lung and other microbiomes.

Gut Microbiome

Future studies investigating the role of the gut microbiome across the lifespan will have far-reaching implications. The health status of an elderly population might be followed by examining their gut microbiome at regular intervals and adjusting diet and nutritional supplements not only to improve physical function, but also to decrease depression and anxiety. Longitudinal studies in the elderly that collect reliable and valid measures of patient-reported outcomes in combination with frequent gut microbiome sampling are feasible in rehabilitation or nursing home settings. Maternal–child health studies are needed to further clarify the role of antibiotics in early childhood and the effects of C-section on the gut microbiomes of infant gut microbiome. Research is needed to identify specific bacteria that can serve as biomarkers in the gut microbiome at all ages, in healthy and diseased populations. An example of a direct clinical application of gut microbiome research and a future direction for nurses is the success of fecal transplants. In recent years, fecal transplants have been very successful in treating patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infections. A recent systematic review that included two randomized control trials, 28 case-series, and two case reports showed fecal microbiome transplant provided resolution of symptoms in 85% of all cases (Drekonja et al., 2015)

An emerging research area that is particularly relevant for nurse scientists is the drug metabolism of xenobiotics or foreign substances by the bacteria in gastrointestinal tract (GI). In contrast to drugs metabolized by the liver, metabolism of foreign compounds by the gut microbiome converts hydrophilic compounds (water soluble) into a hydrophobic form (water insoluble) such that they can absorbed into the body (Kim, 2015; Sousa et al., 2008). However, only a handful of drugs have been reported to be metabolized by GI tract bacteria (Haiser & Turnbaugh, 2013). In this review, the authors listed approximately 40 drugs metabolized by the human gut microbiota (Haiser & Turnbaugh, 2013). One important issue is that the majority of drugs are absorbed in the upper GI tract, whereas the majority of bacteria are located in the large intestine of humans (Klaassen & Cui, 2015; Sousa et al., 2008). There is also limited information available on xenobiotic metabolism in other microbiomes of the human body (Tralau, Sowada, & Luch, 2015). Specific drugs that are metabolized by the GI microbiome have been extensively reviewed in several recent publications (Haiser & Turnbaugh, 2013; H. Li, He, & Jia, 2016; Sousa et al., 2008; Tralau et al., 2015;). We refer the reader to these articles for an in-depth discussion on individual drugs.

Clinically important examples of drugs metabolized by the GI microbiome include sulfasalazine and lactulose. Sulfasalazine is metabolized by azoreductases from bacteria in the distal small bowel and colon to 5-aminosalicylic acid and sulfapyridine (Ardizzone & Bianchi Porro, 2002; Plosker & Croom, 2005). Lactulose is a synthetic metabolized by disaccharidases from bacteria in the colon to lactic acid and acetic acid (Clausen & Mortensen, 1997; Phongsamran, Kim, Cupo Abbott, & Rosenblatt, 2010). Furthermore, relevant issues that should be addressed to facilitate drug metabolism studies during drug development include identification of the specific bacteria involved in drug metabolism, further development of methods to identify metabolites, further development of animal models, and exploring the relationship between hepatic drug metabolizing enzymes and the microbiome (Kang et al., 2013).

Limitations of Current Microbiome Research

Microbiome research is largely descriptive science; few intervention studies exist. Researchers are attempting to describe the human microbiota to understand health and ultimately prevent diseases. Large studies such as the HMP have focused on healthy individuals. Overall, study samples are predominately white and lack significant racial or ethnic diversity. In fact, many studies fail to report the complete demographic information, yet give great detail about the molecular analysis. Evidence indicates microbiome may vary by geography (Nasidze, Li, Quinque, Tang, & Stoneking, 2009). In this study, saliva was sampled and compared with research participants from 12 different global locations. Further work comparing different ethnic and racial groups and their micorbiomes will be important. Small sample size limits the generalizability of most microbiome studies. Larger studies will be more feasible as overall costs of molecular sequencing methods decline and analysis is streamlined. Already, the American Gut Project attempts to address this need through a crowd-sourced study design (http://americangut.org/). Nevertheless, cost remains a practical limitation and judging the most cost-effective option is difficult. Many companies offering molecular techniques exist and consistent prices are not advertised or easily-accessible. The decision to purchase a next-generation sequencer platform and perform DNA extraction and sequencing in-house or to outsource these processes is a major decision point in study planning and design. Limited funding or lack of experienced personnel, including laboratory scientists and bioinformatists, may prohibit in-house investigation. Despite these limitations, microbiome research remains rich, capable of being harnessed to understand health and disease.

Conclusion

The human microbiome represents a fertile area of study for nurse scientists. Molecular sequencing is an essential tool in elucidating the microbiome. Each microbiome has large implications for advancing knowledge of disease occurrences and treatment. Understanding the strengths and the limitations of microbiome research and different methods of microbial identification is crucial to designing clinical studies. As metagenomics rapidly changes and new technologies constantly emerge, it is imperative for scientists to remain current and assemble the interdisciplinary teams required to operationalize, implement, analyze and interpret the human microbiome.

Supplementary Material

Table that details information about studies cited. .doc

Table that presents information about significant gut-brain research studies and their major outcome measures. .doc

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge this work was supported by the Clinical Center Nursing Department, National Institutes for Health.

The authors wish to thank CDR Leslie Wehrlen, RN, MS, OCN, USPHS, for her development of Supplemental Digital Content #2. The authors wish to thank Sarah Mudra, BS, BA, Post-Baccalaureate Intramural Research Award Recipient for manuscript revisions and editing.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Nancy J. Ames, Clinical Nurse Scientist, Nursing Department, National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center, Bethesda, MD.

Alexandra Ranucci, Post-Baccalaureate Intramural Research Award Recipient, Nursing Department, National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center, Bethesda, MD.

Brad Moriyama, Clinical Pharmacist, Pharmacy Department, National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center, Bethesda, MD

Gwenyth R. Wallen, Chief Nurse Officer (Acting), Nursing Department, National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center, Bethesda, MD.

References

- Abreu MT, Peek RM., Jr Gastrointestinal malignancy and the microbiome. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1534–1546e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames NJ, Sulima P, Ngo T, Barb J, Munson PJ, Paster BJ, Hart TC. A characterization of the oral microbiome in allogeneic stem cell transplant patients. PLOS ONE. 2012;7(10):e47628. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardizzone S, Bianchi Porro G. Comparative tolerability of therapies for ulcerative colitis. Drug Safety. 2002;25:561–582. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200225080-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahrani-Mougeot FK, Paster BJ, Coleman S, Barbuto S, Brennan MT, Noll J, … Lockhart PB. Molecular analysis of oral and respiratory bacterial species associated with ventilator-associated pneumonia. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2007;45:1588–1593. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01963-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtiar SM, LeBlanc JG, Salvucci E, Ali A, Martin R, Langella P, … Azevedo V. Implications of the human microbiome in inflammatory bowel diseases. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2013;342:10–17. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barb JJ, Oler AJ, Kim HS, Chalmers N, Wallen GR, Cashion A, … Ames NJ. Development of an analysis pipeline characterizing multiple hypervariable regions of 16S rRNA using mock samples. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(2):e0148047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer KC, Huus KE, Finlay BB. Microbes and the mind: Emerging hallmarks of the gut microbiota-brain axis [Review] Cellular Microbiology. 2016;18:632–644. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck JM, Young VB, Huffnagle GB. The microbiome of the lung. Translational Research: The Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 2012;160:258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger M, Gray JA, Roth BL. The expanded biology of serotonin. Annual Review of Medicine. 2009;60:355–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.042307.110802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmans DCJJ, Bonten MJM, Gaillard CA, Paling JC, van der Geest S, van Tiel FH, … Stobberingh EE. Prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia by oral decontamination: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. American Journal of Respiratory and Crital Care Medicine. 2001;164:382–388. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.3.2005003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj R, Swaminathan S, Salimnia H, Fairfax M, Frey A, Chandrasekar PH. Clinical impact of the use of 16S rRNA sequencing method for the identification of “difficult-to-identify” bacteria in immunocompromised hosts. Transplant Infectious Disease. 2012;14:206–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2011.00687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee S, Lukiw WJ. Alzheimer’s disease and the microbiome [Opinion] Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 2013;7:153. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaser MJ. The microbiome revolution [Review] Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2014;124:4162–4165. doi: 10.1172/jci78366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borre YE, O’Keeffe GW, Clarke G, Stanton C, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Microbiota and neurodevelopmental windows: Implications for brain disorders. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2014;20:509–518. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branch-Elliman W, Wright SB, Howell MD. Determining the ideal strategy for ventilator-associated pneumonia prevention. Cost-benefit analysis. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2015;192:57–63. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201412-2316OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresnahan M, Hornig M, Schultz AF, Gunnes N, Hirtz D, Lie KK, … Lipkin WI. Association of maternal report of infant and toddler gastrointestinal symptoms with autism: Evidence from a prospective birth cohort. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:466–474. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carabotti M, Scirocco A, Maselli MA, Severi C. The gut-brain axis: Interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Annals of Gastroenterology. 2015;28:203–209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson ES, Bittinger K, Chen J, Diamond JM, Li H, Collman RG, Bushman FD. Assessing bacterial populations in the lung by replicate analysis of samples from the upper and lower respiratory tracts. PLOS ONE. 2012;7(9):e42786. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson ES, Bittinger K, Haas AR, Fitzgerald AS, Frank I, Yadav A, … Collman RG. Topographical continuity of bacterial populations in the healthy human respiratory tract. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2011;184:957–963. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201104-0655OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claesson MJ, Jeffery IB, Conde S, Power SE, O’Connor EM, Cusack S, … O’Toole PW. Gut microbiota composition correlates with diet and health in the elderly. Nature. 2012;488:178–184. doi: 10.1038/nature11319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke G, Grenham S, Scully P, Fitzgerald P, Moloney RD, Shanahan F, … Cryan JF. The microbiomegut–brain axis during early life regulates the hippocampal serotonergic system in a sex-dependent manner. Molecular Psychiatry. 2013;18:666–673. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarridge JE., III Impact of 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis for identification of bacteria on clinical microbiology and infectious diseases [Review] Clinical Microbiology Review. 2004;17:840–862. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.4.840-862.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clausen MR, Mortensen PB. Lactulose, disaccharides and colonic flora. Drugs. 1997;53:930–942. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199753060-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente JC, Ursell LK, Parfrey LW, Knight R. The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: An integrative view [Review] Cell. 2012;148:1258–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davari S, Talaei SA, Alaei H, Salami M. Probiotics treatment improves diabetes-induced impairment of synaptic activity and cognitive function: Behavioral and electrophysiological proofs for microbiome-gut-brain axis. Neuroscience. 2013;240:287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK, Venema K, Reijngoud DJ, Bakker BM. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. Journal of Lipid Research. 2013;54:2325–2340. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R036012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRiso AJ, Ladowski JS, Dillon TA, Justice JW, Peterson AC. Chlorhexidine gluconate 0.12% oral rinse reduces the incidence of total nosocomial respiratory infection and nonprophylactic systemic antibiotic use in patients undergoing heart surgery. Chest. 1996;109:1556–1561. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.6.1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desbonnet L, Clarke G, Shanahan F, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Microbiota is essential for social development in the mouse [Letter] Molecular Psychiatry. 2014;19:146–148. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desbonnet L, Clarke G, Traplin A, O’Sullivan O, Crispie F, Moloney RD, … Cryan JF. Gut microbiota depletion from early adolescence in mice: Implications for brain and behaviour. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2015;48:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz Heijtz R, Wang S, Anuar F, Qian Y, Björkholm B, Samuelsson A, … Pettersson S. Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:3047–3052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010529108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson RP, Erb-Downward JR, Martinez FJ, Huffnagle GB. The microbiome and the respiratory tract. Annual Review of Physiology. 2016;78:481–504. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021115-105238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson RP, Erb-Downward JR, Prescott HC, Martinez FJ, Curtis JL, Lama VN, Huffnagle GB. Cell-associated bacteria in the human lung microbiome. Microbiome. 2014;2:28. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding T, Schloss PD. Dynamics and associations of microbial community types across the human body. Nature. 2014;509:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nature13178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Bello MG, Blaser MJ, Ley RE, Knight R. Development of the human gastrointestinal microbiota and insights from high-throughput sequencing. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1713–1719. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Bello MG, Costello EK, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Fierer N, Knight R. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:11971–11975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002601107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drekonja D, Reich J, Gezahegn S, Greer N, Shaukat A, MacDonald R, … Wilt TJ. Fecal microbiota transplantation for clostridium difficile infection: A systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2015;162:630–638. doi: 10.7326/m14-2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudhagara PR, Bhavsar SP, Bhagat C, Ghelani A, Bhatt S, Patel R. Web resources for metagenomics studies. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2015;13:296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Solh AA, Pietrantoni C, Bhat A, Okada M, Zambon J, Aquilina A, Berbary E. Colonization of dental plaques: A reservoir of respiratory pathogens for hospital-acquired pneumonia in institutionalized elders. Chest. 2004;126:1575–1582. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.5.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Aidy S, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Gut microbiota: The conductor in the orchestra of immune-neuroendocrine communication. Clinical Therapeutics. 2015;37:954–967. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Aidy S, Stilling R, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Microbiome to brain: Unravelling the multidirectional axes of communication. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2016;874:301–336. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-20215-0_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erny D, Hrabě de Angelis AL, Jaitin D, Wieghofer P, Staszewski O, David E, … Prinz M. Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nature Neuroscience. 2015;18:965–977. doi: 10.1038/nn.4030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finegold SM, Dowd SE, Gontcharova V, Liu C, Henley KE, Wolcott RD, … Green JA., III Pyrosequencing study of fecal microflora of autistic and control children. Anaerobe. 2010;16:444–453. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourrier F, Duvivier B, Boutigny H, Roussel-Delvallez M, Chopin C. Colonization of dental plaque: A source of nosocomial infections in intensive care unit patients. Critical Care Medicine. 1998;26:301–308. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199802000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghyselinck J, Pfeiffer S, Heylen K, Sessitsch A, De Vos P. The effect of primer choice and short read sequences on the outcome of 16S rRNA gene based diversity studies. PLOS ONE. 2013;8(8):e71360. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill SR, Pop M, Deboy RT, Eckburg PB, Turnbaugh PJ, Samuel BS, … Nelson KE. Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science. 2006;312:1355–1359. doi: 10.1126/science.1124234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorzelak MA, Gill SK, Tasnim N, Ahmadi-Vand Z, Jay M, Gibson DL. Methods for improving human gut microbiome data by reducing variability through sample processing and storage of stool. PLOS ONE. 2015;10( 9):e0134802. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graessler J, Qin Y, Zhong H, Zhang J, Licinio J, Wong ML, … Bornstein SR. Metagenomic sequencing of the human gut microbiome before and after bariatric surgery in obese patients with type 2 diabetes: Correlation with inflammatory and metabolic parameters. Pharmacogenomics Journal. 2013;13:514–522. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2012.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grice EA, Kong HH, Renaud G, Young AC, Bouffard GG, Blakesley RW, … Segre JA. A diversity profile of the human skin microbiota. Genome Research. 2008;18:1043–1050. doi: 10.1101/gr.075549.107. doi:10.1101%2Fgr.075549.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L, McLean JS, Yang Y, Eckert R, Kaplan CW, Kyme P, … He X. Precision-guided antimicrobial peptide as a targeted modulator of human microbial ecology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112:7569–7574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1506207112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haiser HJ, Turnbaugh PJ. Developing a metagenomic view of xenobiotic metabolism. Pharmacological Research. 2013;69:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpin AL, de Man TJB, Kraft CS, Perry KA, Chan AW, Lieu S, … McDonald LC. Intestinal microbiome disruption in patients in a long-term acute care hospital: A case for development of microbiome disruption indices to improve infection prevention. American Journal of Infection Control. 2016;44:830–836. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MJK, Curtin SC, Mathews TJ. Births: Final data for 2014. National Vital Statistics Report. 2015;64(12):1–63. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr64/nvsr64_12.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han YW, Fardini Y, Chen C, Iacampo KG, Peraino VA, Shamonki JM, Redline RW. Term stillbirth caused by oral Fusobacterium nucleatum. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010;115:442–445. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cb9955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo SM, Haase EM, Lesse AJ, Gill SR, Scannapieco FA. Genetic relationships between respiratory pathogens isolated from dental plaque and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients in the intensive care unit undergoing mechanical ventilation. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2008;47:1562–1570. doi: 10.1086/593193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst T, Sichelstiel A, Schär C, Yadava K, Bürki K, Cahenzli J, … Harris NL. Dysregulation of allergic airway inflammation in the absence of microbial colonization. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medine. 2011;184:198–205. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1574OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilty M, Burke C, Pedro H, Cardenas P, Bush A, Bossley C, … Cookson WO. Disordered microbial communities in asthmatic airways. PLOS ONE. 2010;5(1):e8578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston S, Hougland P, Anderson JJ, LaRocco M, Kennedy V, Gentry LO. Effectiveness of 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate oral rinse in reducing prevalence of nosocomial pneumonia in patients undergoing heart surgery. American Journal of Critical Care. 2002;11:567–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua F, Xie H, Worthington HV, Furness S, Zhang Q, Li C. Oral hygiene care for critically ill patients to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016;2016(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008367.pub3. Article: CD008367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Microbiome Project Consortium. A framework for human microbiome research. Nature. 2012a;486:215–221. doi: 10.1038/nature11209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Microbiome Project Consortium. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012b;486:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huse SM, Ye Y, Zhou Y, Fodor AA. A core human microbiome as viewed through 16S rRNA sequence clusters. PLOS ONE. 2012;7(6):e34242. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M, Jeffery IB, Beaumont M, Bell JT, Clark AG, Ley RE, … Steves CJ. Signatures of early frailty in the gut microbiota. Genome Medicine. 2016;8:8. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0262-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumpstart Consortium Human Microbiome Project Data Generation Working Group. Evaluation of 16S rDNA-based community profiling for human microbiome research. PLOS ONE. 2012;7(6):e39315. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang MJ, Kim HG, Kim JS, Oh DG, Um YJ, Seo CS, … Jeong HG. The effect of gut microbiota on drug metabolism. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 2013;9:1295–1308. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2013.807798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai C, Sugimoto K, Moritani I, Tanaka J, Oya Y, Inoue H, … Takase K. Comparison of the gut microbiota composition between obese and non-obese individuals in a Japanese population, as analyzed by terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism and next-generation sequencing. BMC Gastroenterology. 2015;15:100. doi: 10.1186/s12876-015-0330-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keijser BJF, Zaura E, Huse SM, van der Vossen JMBM, Schuren FHJ, Montijn RC, … Crielaard W. Pyrosequencing analysis of the oral microflora of healthy adults. Journal of Dental Research. 2008;87:1016–1020. doi: 10.1177/154405910808701104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JR, Clarke G, Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Brain-gut-microbiota axis: Challenges for translation in psychiatry. Annals of Epidemiology. 2016;26:366–372. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy PJ, Cryan JF, Dinan TG, Clarke G. Irritable bowel syndrome: A microbiome-gut-brain axis disorder? World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;20:14105–14125. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i39.14105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH. Gut microbiota-mediated drug-antibiotic interactions. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 2015;43:1581–1589. doi: 10.1124/dmd.115.063867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaassen CD, Cui JY. Review: Mechanisms of how the intestinal microbiota alters the effects of drugs and bile acids. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 2015;45:1505–1521. doi: 10.1124/dmd.115.065698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korpela K, Salonen A, Virta LJ, Kekkonen RA, Forslund K, Bork P, de Vos WM. Intestinal microbiome is related to lifetime antibiotic use in Finnish pre-school children. Nature Communications. 2016;7:10410. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krajmalnik-Brown R, Ilhan ZE, Kang DW, DiBaise JK. Effects of gut microbes on nutrient absorption and energy regulation. Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 2012;27:201–214. doi: 10.1177/0884533611436116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong JC, McCallum N, Sintchenko V, Howden BP. Whole genome sequencing in clinical and public health microbiology. Pathology. 2015;47:199–210. doi: 10.1097/pat.0000000000000235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauber CL, Zhou N, Gordon JI, Knight R, Fierer N. Effect of storage conditions on the assessment of bacterial community structure in soil and human-associated samples. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2010;307:80–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.01965.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lax S, Gilbert JA. Hospital-associated microbiota and implications for nosocomial infections. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2015;21:427–432. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, He J, Jia W. The influence of gut microbiota on drug metabolism and toxicity. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 2016;12:31–40. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2016.1121234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K, Bihan M, Methé BA. Analyses of the stability and core taxonomic memberships of the human microbiome. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e63139. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Zhou JM. The microbiota-gut-brain axis and its potential therapeutic role in autism spectrum disorder. Neuroscience. 2016;324:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Jiang XY, Zhou LS, Song JH, Zhang X. Effects of probiotics on intestinal mucosa barrier in patients with colorectal cancer after operation: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3342. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000003342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahowald MA, Rey FE, Seedorf H, Turnbaugh PJ, Fulton RS, Wollam A, … Gordon JI. Characterizing a model human gut microbiota composed of members of its two dominant bacterial phyla. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:5859–5864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901529106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mammen MJ, Sethi S. COPD and the microbiome. Respirology. 2016;21:590–599. doi: 10.1111/resp.12732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell GI, Bennett JE, Dolin R. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases. 7. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald D, Birmingham A, Knight R. Context and the human microbiome. Microbiome. 2015;3:52. doi: 10.1186/s40168-015-0117-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizrahi-Man O, Davenport ER, Gilad Y. Taxonomic classification of bacterial 16S rRNA genes using short sequencing reads: Evaluation of effective study designs. PLOS ONE. 2013;8(1):e53608. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi SR, Collins JJ, Relman DA. Antibiotics and the gut microbiota. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2014;124:4212–4218. doi: 10.1172/JCI72333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris A, Beck JM, Schloss PD, Campbell TB, Crothers K, Curtis JL, … Weinstock GM. Comparison of the respiratory microbiome in healthy nonsmokers and smokers. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2013;187:1067–1075. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201210-1913OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller NT, Bakacs E, Combellick J, Grigoryan Z, Dominguez-Bello MG. The infant microbiome development: Mom matters. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2015;21:109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasidze I, Li J, Quinque D, Tang K, Stoneking M. Global diversity in the human salivary microbiome. Genome Research. 2009;19:636–643. doi: 10.1101/gr.084616.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naseer MI, Bibi F, Alqahtani MH, Chaudhary AG, Azhar EI, Kamal MA, Yasir M. Role of gut microbiota in obesity, type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. CNS & Neurological Disorders Drug Targets. 2014;13:305–311. doi: 10.2174/18715273113126660147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Dwyer D, Dickson RP, Moore BB. The lung microbiome, immunity, and the pathogenesis of chronic lung disease. Journal of Immunology. 2016;196:4839–4847. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Mahony SM, Marchesi JR, Scully P, Codling C, Ceolho AM, Quigley EM, … Dinan TG. Early life stress alters behavior, immunity, and microbiota in rats: Implications for irritable bowel syndrome and psychiatric illnesses. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;65:263–267. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson E, Ryan PM, Cryan JF, Dinan TG, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF, Stanton C. Gut microbiota, obesity and diabetes [Review] Postgraduate Medicine Journal. 2016;92:286–300. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew MM, Johnson JK, Harris AD. The human microbiota: Novel targets for hospital-acquired infections and antibiotic resistance [Review] Annals of Epidemiology. 2016;26:342–347. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phongsamran PV, Kim JW, Cupo Abbott J, Rosenblatt A. Pharmacotherapy for hepatic encephalopathy. Drugs. 2010;70:1131–1148. doi: 10.2165/10898630-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plosker GL, Croom KF. Sulfasalazine: A review of its use in the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Drugs. 2005;65:1825–1849. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565130-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punina NV, Makridakis NM, Remnev MA, Topunov AF. Whole-genome sequencing targets drug-resistant bacterial infections. Human Genomics. 2015;9:19. doi: 10.1186/s40246-015-0037-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, Schneider GM, Koenig SSK, McCulle SL, … Forney LJ. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:4680–4687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002611107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond F, Ouameur AA, Déraspe M, Iqbal N, Gingras H, Dridi B, … Corbeil J. The initial state of the human gut microbiome determines its reshaping by antibiotics. ISME Journal. 2016;10:707–720. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehman A, Rausch P, Wang J, Skieceviciene J, Kiudelis G, Bhagalia K, … Ott S. Geographical patterns of the standing and active human gut microbiome in health and IBD. Gut. 2016;65:238–248. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resar R, Pronovost P, Haraden C, Simmonds T, Rainey T, Nolan T. Using a bundle approach to improve ventilator care processes and reduce ventilator-associated pneumonia. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2005;31:243–248. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(05)31031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoads A, Au KF. PacBio sequencing and its applications. Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics. 2015;13:278–289. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridaura VK, Faith JJ, Rey FE, Cheng J, Duncan AE, Kau AL, … Gordon JI. Gut microbiota from twins discordant for obesity modulate metabolism in mice. Science. 2013;341:1241214. doi: 10.1126/science.1241214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutayisire E, Huang K, Liu Y, Tao F. The mode of delivery affects the diversity and colonization pattern of the gut microbiota during the first year of infants’ life: A systematic review. BMC Gastroenterology. 2016;16:86. doi: 10.1186/s12876-016-0498-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saari A, Virta LJ, Sankilampi U, Dunkel L, Saxen H. Antibiotic exposure in infancy and risk of being overweight in the first 24 months of life. Pediatrics. 2015;135:617–626. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Said HS, Suda W, Nakagome S, Chinen H, Oshima K, Kim S, … Hattori M. Dysbiosis of salivary microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease and its association with oral immunological biomarkers. DNA Research. 2014;21:15–25. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dst037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salipante SJ, Sengupta DJ, Rosenthal C, Costa G, Spangler J, Sims EH, … Hoffman NG. Rapid 16S rRNA next-generation sequencing of polymicrobial clinical samples for diagnosis of complex bacterial infections. PLOS ONE. 2013;8(5):e65226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scannapieco FA, Stewart EM, Mylotte JM. Colonization of dental plaque by respiratory pathogens in medical intensive care patients. Critical Care Medicine. 1992;20:740–745. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199206000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schloss PD. Microbiology: An integrated view of the skin microbiome. Nature. 2014;514:44–45. doi: 10.1038/514044a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuijt TJ, Lankelma JM, Scicluna BP, de Sousa e Melo F, Roelofs JJ, de Boer JD, … Wiersinga WJ. The gut microbiota plays a protective role in the host defence against pneumococcal pneumonia. Gut. 2016;65:575–583. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott FI, Horton DB, Mamtani R, Haynes K, Goldberg DS, Lee DY, Lewis JD. Administration of antibiotics to children before age 2 years increases risk for childhood obesity. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:120–129. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segata N, Haake SK, Mannon P, Lemon KP, Waldron L, Gevers D, … Izard J. Composition of the adult digestive tract bacterial microbiome based on seven mouth surfaces, tonsils, throat and stool samples. Genome Biology. 2012;13:R42. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segers P, Speekenbrink RGH, Ubbink DT, van Ogtrop ML, de Mol BA. Prevention of nosocomial infection in cardiac surgery by decontamination of the nasopharynx and oropharynx with chlorhexidine gluconate: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2460–2466. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.20.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. Are we really vastly outnumbered? Revisiting the ratio of bacterial to host cells in humans. Cell. 2016;164:337–340. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snitkin ES, Zelazny AM, Thomas PJ, Stock F, Henderson DK, Palmore TN, Segre JA. Tracking a hospital outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae with whole-genome sequencing. Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4:148ra116. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song SJ, Amir A, Metcalf JL, Amato KR, Xu ZZ, Humphrey G, Knight R. Preservation methods differ in fecal microbiome stability, affecting suitability for field studies. mSystems. 2016;1:e00021–16. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00021-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa T, Paterson R, Moore V, Carlsson A, Abrahamsson B, Basit AW. The gastrointestinal microbiota as a site for the biotransformation of drugs. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2008;363:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan R, Karaoz U, Volegova M, MacKichan J, Kato-Maeda M, Miller S, … Lynch SV. Use of 16S rRNA gene for identification of a broad range of clinically relevant bacterial pathogens. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(2):e0117617. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas V, Clark J, Doré J. Fecal microbiota analysis: An overview of sample collection methods and sequencing strategies. Future Microbiology. 2015;10:1485–1504. doi: 10.2217/fmb.15.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toma I, Siegel MO, Keiser J, Yakovleva A, Kim A, Davenport L, … Simon GL. Single-molecule long-read 16S sequencing to characterize the lung microbiome from mechanically ventilated patients with suspected pneumonia. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2014;52:3913–3921. doi: 10.1128/jcm.01678-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tralau T, Sowada J, Luch A. Insights on the human microbiome and its xenobiotic metabolism: What is known about its effects on human physiology? Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 2015;11:411–425. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2015.990437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsurugizawa T, Uematsu A, Nakamura E, Hasumura M, Hirota M, Kondoh T, … Torii K. Mechanisms of neural response to gastrointestinal nutritive stimuli: The gut-brain axis. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:262–273. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, Ley RE, … Gordon JI. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457:480–484. doi: 10.1038/nature07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent AT, Derome N, Boyle B, Culley AI, Charette SJ. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) in the microbiological world: How to make the most of your money. Journal of Microbiological Methods. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2016.02.016. (in press) doi:1016/j.mimet.2016.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]