Abstract

Molybdenum is an essential nutrient for metabolism in plant, bacteria, and animals. Molybdoenzymes are involved in nitrogen assimilation and oxidoreductive detoxification, and bioconversion reactions of environmental, industrial, and pharmaceutical interest. Molybdoenzymes contain a molybdenum cofactor (Moco), which is a pyranopterin heterocyclic compound that binds a molybdenum atom via a dithiolene group. Because Moco is a large and complex compound deeply buried within the protein, molybdoenzymes are accompanied by private chaperone proteins responsible for the cofactor’s insertion into the enzyme and the enzyme’s maturation. An efficient recombinant expression and purification of both Moco-free and Moco-containing molybdoenzymes and their chaperones is of paramount importance for fundamental and applied research related to molybdoenzymes. In this work, we focused on a D1 protein annotated as a chaperone of steroid C25 dehydrogenase (S25DH) from Sterolibacterium denitrificans Chol-1S. The D1 protein is presumably involved in the maturation of S25DH engaged in oxygen-independent oxidation of sterols. As this chaperone is thought to be a crucial element that ensures the insertion of Moco into the enzyme and consequently, proper folding of S25DH optimization of the chaperon’s expression is the first step toward the development of recombinant expression and purification methods for S25DH. We have identified common E. coli strains and conditions for both expression and purification that allow us to selectively produce Moco-containing and Moco-free chaperones. We have also characterized the Moco-containing chaperone by EXAFS and HPLC analysis and identified conditions that stabilize both forms of the protein. The protocols presented here are efficient and result in protein quantities sufficient for biochemical studies.

Keywords: chaperone protein, molybdenum cofactor, thermofluor shift assay, molybdoenzymes

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Molybdoenzymes use a wide range of substrates to catalyze diverse redox reactions in bacteria, plants, and animals. Bacterial molybdoenzymes are responsible, for example, for anaerobic respiration, degradation of aromatic and aliphatic hydrocarbons [1] and oxochlorate [2,3], and metabolism of arsenate [4] and sulfate [5]. In plants, molybdoenzymes take part in nitrate assimilation (nitrate reductases), purine catabolism (xanthine dehydrogenase) [6], hormone synthesis (aldehyde oxidase), and detoxification (sulfite oxidase) [7]. Similarly, in humans, several molybdoenzymes have been identified including xanthine oxidoreductase [8], sulfite and aldehyde oxidase [9], and mitochondrial amidoxime reducing components 1 and 2 (mARC1 and mARC2) [10,11]. The plethora of substrates capable of being utilized by molybdoenzymes prompted researchers to investigate their potential applications in bioremediation [1,2], agriculture [12], drug synthesis and medicine [13].

The crucial component of molybdoenzymes is a structure called the molybdenum cofactor (Moco) [14] that forms the active site of the molybdoenzyme. In Moco, a pterin, known as molybdopterin (MPT), serves as a scaffold for the molybdenum atom. Moco must be synthesized de novo in a cell, and the process of Moco synthesis is complex, involving several synthesis pathways and requiring facilitation by multiple proteins [15]. The cofactor moiety isolated from molybdoenzymes is very unstable, and currently, Moco precursors are obtained through chemical synthesis, or isolation and subsequent derivatization of Moco obtained from natural sources [16].

Proteins belonging to the dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) reductase family contain the bis-molybdopterin guanine dinucleotide (bis-MGD) type of Moco. In bis-MGD, the molybdenum atom is coordinated through two dithiolene groups of two MGD moieties [17–19]. In E. coli, the in vivo process of production of bis-MGD cofactor consists of four main steps: a) the conversion of GTP into cyclic pyranopterin monophosphate (cPMP) by S-adenosyl methionine (SAM)-dependent radical enzymes [20] and cyclic pyranopterin monophosphate synthase accessory protein, b) the insertion of sulfur and formation of molybdopterin (MPT) by MPT synthase [21,22], c) the insertion of molybdenum, which is sequestered as a molybdate oxyanion (MoO42−) [23] into MPT by molybdopterin adenylyltransferase (MogA) [24] and molybdopterin molybdenumtransferase (MoeA) [18] and d) the further modification of Moco to form a dinucleotide derivative of Moco, the MPT-guanine dinucleotide (MGD) cofactor.

The malfunctions of molybdoenzymes due either to mutations in the enzymes or insufficient molybdenum cofactor production can cause various diseases in humans. For example xanthinuria can be caused by a mutation in the gene coding for xanthine dehydrogenase [25], and a molybdenum cofactor deficiency (MoCD) type A is a rare metabolic disease caused by mutations in genes coding for proteins involved in a cofactor synthesis. Improper functioning of molybdoenzymes can result in increased levels of metabolites (sulfites) that are toxic if not broken down. MoCDs are linked to brain dysfunction and neurological damage, treatable by daily injections with cofactor precursor, cPMP [26].

Because redox molybdoenzymes (such as steroid C25 dehydrogenase (S25DH) [27], ethylbenzene dehydrogenase (EBDH) [1], nitrate reductase (NarGH) [28], and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) reductase [29] require cofactor insertion in the cytoplasm, they can only be transported through the membrane in a folded form [30]. A Moco insertion step into an apo-enzyme is assisted by a chaperone protein. Almost all molybdoenzymes have a private chaperone protein that binds Moco and inserts it into the target apo-enzyme [31]. Subsequently, molybdoenzyme can be transported through membranes through a TAT-pathway which allows for translocation of fully folded proteins across biological membranes [32]; TAT-pathway substrates possess a characteristic N-terminal amino acid sequence motif that is recognized by a protein from TAT-pathway system [33]. Our focus of this work revolved around a D1 chaperone protein that is considered responsible for loading a maturated form of Moco to the α subunit of S25DH from Sterolibacterium denitrificans (Chol-1ST, DSMZ 13999T) [34] and for transport regulation of folded S25DH enzyme across the membrane via the TAT-pathway [27].

S25DH catalyzes the oxygen-independent hydroxylation of the tertiary C25 carbon atom of the aliphatic side chain of cholesterol and other sterol compounds as well as sterol derivatives (e.g. calciferol) [13,35] to the respective tertiary alcohol [27]. S25DH is a heterotrimer with αβγ composition that belongs to the DMSO reductase family. The α subunit contains bis-MGD and an iron-sulfur cluster, the β subunit contains four iron sulfur clusters, and the γ subunit contains a heme b[27]. S25DH can be used as a catalyst in the industrial production of calcifediol, which is used in the treatment of vitamin D3 deficiency and rickets [13,36], or 25-hydroxycholesterol, which is an important regulator of immune function [37,38]. An efficient overexpression system could also expedite research regarding the reaction mechanism of hydroxylation of tertiary carbon atoms by structural experiments combined with computational studies (Rugor et al., to be published).

E. coli is a prokaryotic model organism that plays an important role in industrial microbiology, biotechnology, and genetic engineering, both in research and application [39]. It is a facultative anaerobe whose metabolism can change in the presence or absence of oxygen. Under aerobic conditions, E. coli uses O2 as a terminal electron acceptor, while it grows anaerobically by fermentation or respiration [40]. When E. coli respires under anaerobic conditions, it can use acceptors such as nitrate, DMSO, trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), or fumarate [41]. The presence of an electron acceptor induces the expression of a specific reductase: for example, TMAO reductase is expressed in the presence of TMAO, and DMSO and fumarate reductases are expressed when sulfoxides or fumarate are present, respectively [42]. On the molecular level, an FNR (fumarate-nitrate reduction) [43] transcription regulator is responsible for the switch between aerobic and anaerobic respiration in E. coli. Under anaerobic conditions, the FNR monomer acquires the [4Fe-4S]2+ cluster, and the protein dimerizes and binds to the promotor regions of target genes, leading to the activation of genes whose products function in anaerobic energy metabolism [44–46]. The presence of O2 leads to the decomposition of the [4Fe-4S]2+ cluster and FNR dimer by monomer dissociation [47] and subsequent repression of expression of genes involved in anaerobic respiration.

E. coli is an organism widely used in the overproduction of recombinant proteins. One of the main obstacles in S25DH heterologous overexpression may be the lack of an efficient molybdenum cofactor production by E. coli. Although successful overexpression under anaerobic conditions of recombinant molybdoenzyme such as nitrate reductase A (NarGHI) [48] or DmsABC [41,49,50] has been reported, it is unclear if the E. coli Moco loading machinery is compatible with recombinant S. denitrificans proteins.

For proteins overexpressed under aerobic conditions, E. coli can be cultured on either rich, minimal, defined, or undefined media [51,52], depending on the need of further experiments. When recombinant protein production is carried out in E. coli under anaerobic conditions, an electron acceptor is added to the growth medium to allow for anaerobic respiration. Under anaerobic conditions, the presence of nitrate guarantees the overexpression of nitrate reductase [53]. The addition of DMSO or fumarate to the culture medium ensures that E. coli uses these compounds as terminal electron acceptors for growth.

Apart from studies on the biochemistry of molybdoenzymes, chaperone proteins involved in their maturation such as NarJ [54], DmsD [55] or TorD [56] from E. coli have been also studied. So far, little is known about the D1 chaperone responsible for S25DH maturation or cofactor loading. Here, we present our efforts to optimize both the production of the Moco in E. coli during the overexpression of D1 protein and the yield of the D1 chaperone in both Moco-containing and Moco-free forms. The presented protocols were suitable for further analysis of the protein by extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS), high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and thermofluor shift assays.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genetic construct preparation

Using the StarGate® system (IBA GmbH, Göttingen, Germany), the D1 gene (GeneBank: JQ292999.1) of S25DH was cloned into the pASG-IBA5 and pASG-IBA35 vectors according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer. The initial pEntry vector with the D1 gene was obtained from a laboratory stock (the D1 gene was cloned from S. denitrificans genomic DNA). The resulting plasmids were referred to as pASG-IBA5+D1 and pASG-IBA35 + D1. To prepare expression vectors using the MCSG system [57], the gene coding for D1 was amplified using the following oligonucleotides: D1_For: TACTTCCAATCCAATGCCATGCAAATGAGCAATGCAAACAATACGG, and D1_Rev: TTATCCACTTCCAATGTTAATGTGGCGTGCCGGCCTTCTGC, and the gene was then cloned into the pMCSG7 vector using the protocol described in Ref. [57]. Oligonucleotides for PCR reactions were synthesized by Genomed (Warsaw, Poland). The resulting plasmid was referred to as pMCSG7+D1. Schematic diagrams of vectors used in this study are presented in Supplemental Fig. S1.

Bacterial strains

During the course of the study two E. coli strains, DH5α (#18265017, LifeTechnologies) and BL21(DE3)RILP (#230280, Agilent Technologies) were used. These strains were tested for efficient overexpression of the D1 protein (Uniprot ID: H9NN97). Unless mentioned otherwise, both strains are collectively referred to as “E. coli” in the following subsections.

Selecting the vector type (pASG-IBA5 vs pASG-IBA35)

E. coli cells harboring pASG-IBA5+D1 or pASG-IBA35+D1 plasmids were grown aerobically in 50 mL of Luria-Bertani (LB) medium with ampicillin (#K029.4, Carl Roth) at a final concentration of 100 μg/mL overnight at 37 °C. For anaerobic cultures, 400 mL of LB or M9ZB media were prepared in a 500 mL bottle. The bottle was closed with a rubber stopper, degassed with N2, and autoclaved. The overnight aerobic culture was transferred to the medium through a syringe, without opening the bottle. Cells were cultured at 37 °C in the presence of ampicillin (100 μg/mL) with shaking until they reached an OD600 of 0.8. 15 mins before induction, the culture was supplemented with Na2MoO4 to a final concentration of 10 mM. Protein production was induced by addition of anhydrotetracycline (AHT) (#37919, Sigma-Aldrich) to a final concentration of 0.2 μg/mL. Overexpression was carried out at 18 °C overnight or for 2 h at 37 °C. To test the aerobic conditions, the overnight aerobic culture was transferred to 200 mL LB medium containing ampicillin (100 μg/mL). 15 min before AHT induction the culture was supplemented with Na2MoO4 as for anaerobic conditions.

Investigation of growth conditions and medium type

E. coli cells harboring the pASG-IBA35+D1 plasmid were grown aerobically in 50 mL of LB medium overnight at 37 °C. The overnight bacterial culture was transferred to LB or M9ZB medium. In all tested conditions 100 μg/mL ampicillin (#K029.4, Carl Roth) was used for antibiotic selection.

For anaerobic cultures, the 400 mL of LB or M9ZB media were prepared in a 500 mL bottle that was closed with a rubber stopper, degassed with N2 and sterilized by autoclaving. The overnight aerobic culture was transferred to the medium through a syringe, without opening the bottle. In the case when the M9ZB medium was tested, cells were grown at 37 °C with shaking, and induced with AHT (0.2 μg/mL final) when the culture reached an OD600 of 0.8. When cells grew anaerobically in LB medium, they were induced at an OD600 of 0.5. The culture was supplemented with Na2MoO4 (10 mM final concentration) 15 min before induction with AHT (0.2 μg/mL final). The culture was grown for 2 h at 37 °C and then cells were pelleted. The pellet was stored at −80 °C for a few days before purification.

Aerobic expression: pMCSG7+D1 in BL21(DE3)RILP cells

For expression under aerobic conditions BL21 (DE3)RILP cells harboring the pMCSG7 plasmid with the D1 gene were grown in 50 mL of Lennox LB medium (#LBL405, BioShop Canada Inc.) with 100 μg/mL ampicillin (#K029.4, Carl Roth) and 34 μg/mL chloramphenicol (#227920250, Acros Organics) overnight at 37 °C with shaking. The next day, the culture was transferred to 4 L of Terrific-Broth (TB) medium (#TER409, BioShop Canada Inc.) with ampicillin and chloramphenicol for selection, and cells were grown at 37 °C until the culture reached an OD600 of 1.2. The temperature was decreased to 18 °C, and cells were induced with 0.15 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (#CN08.3, Carl Roth). Protein production took place overnight at 18 °C. Cells were centrifuged and the pellet was stored at −80 °C for a few days before purification.

Purification of D1 protein expressed from pASG-IBA5 vector in DH5α cells under anaerobic conditions

Protein purification was carried out under N2 atmosphere (N2/H2 filled glovebox, Coy Laboratory Products). Cell pellets were suspended in 10 mL of a lysis buffer containing 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, DNase (#10104159001, Roche), lysozyme (#8259.2, Roth) and protease inhibitor (cOmplete, EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets, Roche). Cells were sonicated for 3 min with 3 s on and 5 s off, and the lysate was clarified by centrifugation for 40 min at 40 000 rcf. Lysates were applied to 0.5 mL of Strep-Tactin® Sepharose® resin (#2-1201-010, IBA GmbH) equilibrated with the lysis buffer. Resin with bound protein was washed with 5 mL of the lysis buffer. The protein was eluted with a buffer containing 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl and 2.5 mM desthiobiotin (#2-1000-002, IBA GmbH).

Purification of D1 protein expressed from pASG-IBA35 vector in DH5α cells under anaerobic conditions (D1anaerobic)

Protein purification was carried out under N2 atmosphere (N2/H2 filled glovebox, Coy Laboratory Products). Cell pellets were suspended in 10 mL of a lysis buffer containing 2 mM imidazole, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.7, 150 mM NaCl, DNase (#10104159001, Roche), lysozyme (#8259.2, Roth) and protease inhibitors (cOmplete, EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets, Roche). Cells were sonicated for 3 min with 3 s on and 5 s off, and the lysate was clarified by centrifugation for 40 min at 40 000 rcf. The lysate was applied to 750 μL of NiNTA (#2-3206-010, IBA GmbH) resin equilibrated with lysis buffer. Resin with bound protein was washed with 5 mL of a buffer containing 10 mM imidazole, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.7, and 600 mM NaCl. The protein was eluted with a buffer containing 250 mM imidazole, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.7, and 150 mM NaCl. D1anaerobic was concentrated on Amicon® Ultra filters (#UFC901024, Millipore) with a 10 kDa cut-off to a final concentration of 14 mg/mL, as measured by a Bradford assay.

Purification of D1 protein expressed from pMCSG7 vector in BL21(DE3)RILP cells under aerobic conditions (D1aerobic)

For aerobic protein purification, the cell pellet was suspended in 100 mL of a lysis buffer composed of 2 mM imidazole, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.7, 150 mM NaCl, DNase (#10104159001, Roche), lysozyme (#8259.2, Roth), and protease inhibitors (cOmplete, EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets, Roche). Cells were sonicated for 10 min with 3 s on and 5 s off, and the lysate was clarified by centrifugation for 40 min at 40 000 rcf. The lysate was applied to 3 mL of NiNTA (#2-3206-010, IBA GmbH). The resin with bound protein was washed with 5 mL of buffer containing 10 mM imidazole, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.7, and 600 mM NaCl. The protein was eluted with a buffer containing 250 mM imidazole, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.7, and 150 mM NaCl. The N-terminal 6xHis-tag was removed by recombinant 6xHis-tagged Tobacco Etch Virus (rTEV). Proteolytic cleavage was carried out overnight at 4 °C during dialysis in 1 L of a digestion buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl 7.9, 150 mM NaCl and β-mercaptoethanol. To remove the rTEV protease, cleaved tag, and uncut protein the dialyzed protein was loaded onto 3 mL of NiNTA resin previously equilibrated with the digestion buffer. Flow through was collected, concentrated using Amicon® Ultra filters (#UFC901024, Millipore) with a 10 kDa cut-off, and loaded onto a size exclusion Superdex200 column equilibrated with digestion buffer (without β-mercaptoethanol) attached to AKTA FPLC purification system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Fractions containing the D1 protein were pooled together and concentrated on Amicon® Ultra filters with a 10 kDa cut-off to 14 mg/mL or 18 mg/mL, as measured by absorbance at 280 nm using a Biotek Epoch plate reader.

Analysis of molybdenum content

Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) analyses were carried out using an ELAN 6100 mass spectrometer (Perkin Elmer). According to the certification the molybdenum detection level was in a range between 0.3 nM and 10 μM. A buffer, in which analyzed protein was stored, was used as a blank. Molybdenum content in each protein sample was compared to its content in the buffer control. The final volume of each sample was 5 mL and the protein concentration used for analysis was 10 μM.

Crystallization trials

Crystallization of D1 protein was performed under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions. For anaerobic conditions, crystallization trials for D1 were set in a glove box using the following crystallization screens: Index (#HR2-144) and SaltRx (#HR2-107 and #HR2-109) from Hampton Research. For aerobic trials crystallization of D1 was set up using the following screens: Peg Ion (#HR-2-139) and Crystal Screen (#HR2-133) from Hampton Research, TOP96 (#TOP96-10ML), MCSG1 (#MCSG1-4T), MCSG2 (#MCSG2-4T), MCSG3 (#MCSG3-4T), and MCSG4 (#MCSG4-4T) from Anatrace. In case of D1aerobic protein, different concentrations of protein were tested: 6 mg/mL, 8 mg/mL, 10 mg/mL, 12 mg/mL, and 18 mg/mL. Under anaerobic conditions, a crystallization drop was constituted by mixing protein with a crystallization buffer in a glovebox as a sitting drop. Under aerobic conditions, drops were set as a sitting drop against 1.5 M NaCl using 0.2 μL of commercially available crystallization screens and 0.2 μL of protein using Mosquito (TTP Labtech). Optimization of crystallization conditions that gave positive hits in aerobic conditions was done using Optimatrix Maker (Rigaku). Crystallization experiments of D1aerobic in complex with guanine and/or ammonium molybdate, and streptomycin were also set. Preliminary diffraction data were collected using SuperNova diffractometer (Rigaku Oxford Diffraction) equipped with microfocus CuKα (1.54 Å) and CCD Atlas detector. Data was indexed using HKL3000 [58].

Thermofluor shift assay (TSA)

A thermofluor shift assay was used to screen for conditions (such as buffering compound or the presence of ligands) that may stabilize or destabilize a protein [59]. Initial concentrations of D1aerobic and D1anaerobic protein, and SYPRO Orange label (#S6651, LifeTechnologies) were checked in a test run. The assay was carried out in a 96-well plate (Hard-Shell PCR Plates # HSP9601, BioRad) in a CFX Connect (buffer screening) or CFX 96 (ligand screening) Real-Time PCR (BioRad). The total reaction volume was 25 μL. D1 protein in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 and 150 mM NaCl was tested at 4 concentrations: 0.5 mg/mL, 1 mg/mL, 2 mg/mL, and 4 mg/mL. SYPRO Orange concentration was tested at dilutions 1:5000 and 1:2500 of the 5000× concentrated stock solution prepared in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 and 150 mM NaCl.

Buffers and ligand screening were done using a similar protocol as was used for protein concentration tests with a few exceptions. 2.5 μL of D1aerobic at 18 mg/mL in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 and 150 mM NaCl buffer was mixed with 1 μL of the working stock solution of SYPRO Orange. The SYPRO Orange working stock solution was prepared by a 100× dilution of the 5000× concentrated stock solution in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 and 150 mM NaCl. For buffer screening, the solution of respective buffer was added to the sample for the final volume to be 25 μL. The compositions of buffers are presented in Table 1. For ligand screening, 5 μL of the ligand was added to the sample followed by addition of 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 to a final volume of 25 μL. The list of ligands is presented in Table 2. All solutions of ligands were prepared in water. Protein, buffers, and ligands were added to wells in a 96-well plate (Hard-Shell PCR Plates, BioRad) with a multichannel pipette. The 96-well plates were sealed with Optical Sealing Tape (BioRad, #2239444) and centrifuged at 200 rpm for 2 min. Unfolding curves were generated using a temperature gradient from 20 °C to 95 °C with a heating rate of 1 °C/min. Melting temperature values (Tm) were determined from the maximum of the first derivative of the raw data.

Table 1.

Composition of buffers used in TSA analysis.

| Buffer number | Compound (100mM) | Mass ratio | Supplier |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Succinic acid | 2 | Bioshop (Suc444) |

| Sodium dihydrogen phosphate | 7 | Sigma (S9638) | |

| Glycine | 7 | Sigma (G7126) | |

|

| |||

| 2 | Citric acid anhydrous | 2 | Bioshop (CIT002) |

| HEPES | 3 | Sigma (H3375) | |

| CHES | 4 | Sigma (C2885) | |

|

| |||

| 3 | Malonic acid | 2 | Sigma (M1296) |

| Imidazole | 3 | Acros Organics (288324) | |

| Boric acid | 3 | Poch (531360115) | |

|

| |||

| 4 | Sodium propionate | 2 | Sigma (P1880) |

| Sodium cacodylate | 1 | Sigma (CO250) | |

| Bis-Tris propane | 2 | Bioshop (BTP501) | |

|

| |||

| 5 | Sodium acetate | 1 | Poch (805670119) |

| Bis-Tris | 1 | Roth (9140.3) | |

| Bicine | 1 | Bioshop (BIC703) | |

|

| |||

| 6 | L-Malic | 1 | Sigma (M8307) |

| MES | 2 | Sigma (M8250) | |

| Tris | 2 | Bioshop (TRS001) | |

|

| |||

| 7 | Sodium tartrate dihydrate | 3 | Sigma (S4797) |

| Bis-Tris | 2 | Roth (9140.3) | |

| Glycylglycine | 2 | Bioshop (GGL888) | |

Table 2.

A list of ligands used in TSA experiments.

| Group | Compound | Concentration | Supplier |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aminoacids | L-Asparagine | 30 mM | Sigma A0884 |

| L-Tryptophan | 30 mM | Sigma 93659 | |

| L-Tyrosine | 30 mM | Sigma T3754 | |

| L-Leucine | 30 mM | Sigma L8912 | |

| L-glutamine | 30 mM | Sigma G8540 | |

| L-Phenylalanine | 30 mM | Sigma P2126 | |

| L-Histidine | 30 mM | Sigma H6034 | |

| L-Methionine | 30 mM | Sigma M5308 | |

| L-Cysteine | 30 mM | Sigma C7352 | |

| L-Lysine | 30 mM | Acros 173730250 | |

| L-Arginine | 30 mM | Sigma A5006 | |

|

| |||

| Sugars | α-D-Glucose | 10 mM | Aldrich 158968 |

| D-(−)-Fructose | 10 mM | Sigma F0127 | |

| D-Sorbitol | 10 mM | Sigma S3889 | |

| D-(+)-Mannose | 10 mM | Fluka 63582 | |

| L-(−)-Fucose | 10 mM | Sigma F2252 | |

| D-(+)-Galactose | 10 mM | Sigma-Aldrich G6404 | |

| D-(+)-Glucosamine hydrochloride | 10 mM | Sigma G4875 | |

| α-D-Glucose 1-phosphate disodium salt hydrate | 2 mM | Sigma G7000 | |

| α-D-Galactosamine 1-phosphate | 2 mM | Sigma G5134 | |

|

| |||

| Antibiotics | Apramycin sulfate salt | 10 mM | Sigma A2024 |

| Ampicillin sodium salt | 10 mM | Sigma-Aldrich A9518 | |

| Paromomycin sulfate salt | 10 mM | Sigma P5057 | |

| Cefuroxime sodium salt | 10 mM | Sigma C4417 | |

| Tetracycline | 10 mM | Sigma 87128 | |

| Streptomycin sulfate salt | 10 mM | Sigma-Aldrich S6501 | |

| Cephalosporin C zinc salt | 10 mM | Sigma 3270 | |

|

| |||

| Nucleosides | Adenosine 5′-diphosphate sodium salt | 2 mM | Sigma A2754 |

| Guanosine 5′-triphosphate sodium salt hydrate | 2 mM | Sigma 8877 | |

| Adenosine 5′-triphosphate disodium salt hydrate | 2 mM | Sigma A7699 | |

| Adenosine 5′-monophosphate disodium salt | 2 mM | Sigma 01930 | |

| Guanosine 5′-diphosphate sodium salt | 2 mM | Sigma G7127 | |

| Cytidine 5′-monophosphate disodium salt | 2 mM | Sigma C1006 | |

| Thymidine 3′:5′-cyclic monophosphate sodium salt | 2 mM | Sigma T6754 | |

|

| |||

| Cofactors | β-Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide hydrate | 2mM | Sigma-Aldrich N7004 |

| β-Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, reduced disodium salt hydrate | 2mM | Sigma N8129 | |

| β-Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide 2′-phosphate reduced tetrasodium salt hydrate | 2mM | Sigma N1630 | |

| Flavin adenine dinucleotide disodium salt hydrate | 10 mM | Sigma F6625 | |

|

| |||

| CoA and derivatives | Coenzyme A sodium salt hydrate | 10 mM | Sigma C3144 |

| Acetyl coenzyme A lithium salt | 10 mM | Sigma A2181 | |

| Palmitoyl coenzyme A lithium salt | 10 mM | Sigma P9716 | |

| Malonyl coenzyme A lithium salt | 10 mM | Sigma M4263 | |

| Isobutyryl coenzyme A lithium salt | 10 mM | Sigma I0383 | |

| DL-β-Hydroxybutyryl coenzyme A lithium salt | 10 mM | Sigma H0261 | |

|

| |||

| Reducing agents | DL-Dithiothreitol (DTT) | 5 mM | Promega V3155 |

| 2-Mercaptoethanol | 5 mM | Aldrich M6250 | |

| Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP) | 5 mM | Aldrich C4706 | |

|

| |||

| Salts | Sodium chloride | 10 mM | Fisher Scientific S6403 |

| Cadmium chloride | 10 mM | Fluka 20906 | |

| Ammonium Molybdate | 10 mM | Fisher Scientific A-674 | |

| Zinc chloride | 10 mM | Sigma-Aldrich 208086 | |

| Nickel(II) chloride hexahydrate | 10 mM | Sigma N5766 | |

| CoCl2 | 10 mM | Sigma C-3169 | |

| CuCl2 | 10 mM | Sigma-Aldrich 307483 | |

| MgCl2 | 10 mM | J. T. Baker 2444-01 | |

| Ammonium sulfate | 10 mM | Sigma-Aldrich A4915 | |

|

| |||

| Denaturating agents | Urea | 10 mM | Fisher Scientific U15-3 |

| Urea | 1 M | Fisher Scientific U15-3 | |

| Urea | 3.5 M | Fisher Scientific U15-3 | |

| Guanidine hydrochloride | 10 mM | Sigma G3272 | |

| Guanidine hydrochloride | 1 M | Sigma G3272 | |

| Guanidine hydrochloride | 3.5 M | Sigma G3272 | |

|

| |||

| Buffers | Tris | 100 mM | RPI T60044 |

| Tris 100 mM 50 mM sodium citrate | 100 mM / 50 mM | RPI T60044 / Sigma S4641 | |

| Tris 100 mM 50 mM imidazole | 100 mM / 50 mM | RPI T60044 / Sigma-Aldrich 56750 | |

| HEPES | 100 mM | Fisher Scientific BP310 | |

| MES | 100 mM | Sigma M3671 | |

| BisTris | 100 mM | Sigma B9754 | |

| BisTris Propane | 100 mM | Sigma B9410 | |

| MOPS | 100 mM | Sigma M1254 | |

| CHES | 100 mM | Sigma C2885 | |

|

| |||

| Others | Glycerol | 20% | Alfa Aesar A16205 |

| Caffeine | 2 mM | Sigma-Aldrich C0750 | |

| Adenine hydrochloride | 2 mM | Sigma A8751 | |

| Cytosine | 2 mM | Sigma C3506 | |

| Xanthine | 2 mM | Fluka 95490 | |

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC FPLC)

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) analysis was carried out on an AKTA FPLC purification system using a Superdex200 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with a buffer composed of 50 mM Tris-HCl 7.8 and 150 mM NaCl. Two samples of D1 protein were used, one with 10 mM of dithiothreitol (DTT) and the other without a reducing agent. 15 nmol of each sample of D1aerobic protein were injected onto the column. 0.1 μmol of guanosine diphosphate (GDP) were added to the sample to check possible binding to D1aerobic. Protein molecular mass was evaluated based on a calibration curve prepared using the following protein standards: ferritin–440 kDa, conalbumin–75 kDa, carbonic anhydrase–29 kDa, and ribonuclease 14 kDa. Standards were purchased from GE Healthcare Life Sciences.

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC HPLC)

HPLC analysis was carried out on Agilent 1100 VL LC/MSD using a Yarra SEC-2000 column (Phenomenex). The column was equilibrated with 6M guanidine-HCl and 50 mM sodium phosphate pH 6.5 buffer. 20 μL of the D1anaerobic protein were transferred into a glass vial under anaerobic atmosphere, and 20 μL of buffer composed of 8M guanidine-HCl and 50 mM sodium phosphate pH 6.5 were added to the protein. 20 μL of D1aerobic protein was mixed with 20 μL of the same buffer under aerobic conditions. A reducing agent (DTT) was added where indicated into protein samples. The mobile phase did not contain DTT. 10 μL samples were injected into the column. Protein molecular mass was evaluated based on calibration curve prepared using following protein standards: conalbumin–75 kDa, ovoalbumin–44 kDa, and ribonuclease 14 kDa. Standards were purchased from GE Healthcare Life Sciences.

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy

X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) was carried out as previously described in detail [60]. Samples for XAS were loaded into 2 × 10 × 10 mm acrylic sample cuvettes within an anaerobic glove box and frozen using a liquid nitrogen-cooled cold block. XAS data were acquired at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) with the SPEAR storage ring containing 500 mA at 3.0 GeV. Data were collected using the structural molecular biology XAS 7-3 and 9-3, both of which are equipped with Si(220) double crystal monochromators, and Rh coated mirrors, with the mirror set so that critical angle corresponds to about 23 keV in order to reject harmonics. The use of an upstream vertically collimating mirror combines excellent monochromator energy resolution and energy stability. Incident and transmitted X-ray intensities were monitored using nitrogen-filled ionization chambers using a sweeping voltage of 1.8 kV to ensure the linear response of the ionization chambers, and X-ray absorption was measured as the Mo Kα fluorescence excitation spectrum using an array of 30 germanium detectors [61] together with zirconium filters and a Soller slit assembly to preferentially reject scattered radiation so as to maintain the detector count rate in the pseudo-linear regime. High-speed analog detector readout electronics were used with a Gaussian shaping time of 0.125 μs. Samples were maintained at a temperature of approximately 10K during data collection using an Oxford instruments liquid helium flow cryostat. For each data set, between eight and fourteen scans each of 40 minutes duration were accumulated, and the energy was calibrated by reference to the absorption of a molybdenum foil measured simultaneously with each scan, assuming a lowest energy inflection point of 20003.9 eV. The energy threshold of the extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) oscillations (k = 0 Å−1) was assumed to be 20025.0 eV.

XAS data analysis

The EXAFS oscillations χ(k) were quantitatively analyzed by curve-fitting using the EXAFSPAK suite of computer programs [http://ssrl.slac.stanford.edu/exafspak.html] as previously described [62], using ab initio theoretical phase and amplitude functions calculated using the program FEFF version 8.25 [63]. No smoothing, filtering or related operations were performed on the data.

RESULTS

The D1 chaperone is a link between E. coli-synthesized Moco and recombinant overexpressed S25DH. The first goal of this project was to optimize growth conditions for efficient production of the Moco-loaded D1 chaperone which, would allow for protocols suitable for producing active recombinant S25DH. The second goal was to develop a method for obtaining high amounts of soluble protein for biophysical and biochemical studies. The developed methods should allow for selective production of both Moco-loaded and Moco-free D1 protein. This feature would streamline further studies on the mechanism of Moco loading by the molybdenum enzyme chaperones.

Optimization of the genetic construct and purification strategy

Optimization of purification methods was conducted before comparing affinity purification systems based on His-tag and Strep-tag. Under aerobic and anaerobic growth conditions, we tested two vectors: pASG-IBA5, which harbors an N-terminal Strep-tag, and pASG-IBA35, which harbors an N-terminal 6xHis-tag. In all cases, DH5α cells were used. Expression and purification utilizing pASG-IBA35 + D1 and immobilized Ni2+ metal affinity chromatography (Ni2+IMAC) were found to be superior to protocols using the pASG-IBA5+D1 vector: a) in anaerobic conditions, the yield of purified D1 protein was 20× higher for pASG-IBA35 + D1 than for pASG-IBA5+D1 (4.25 mg compared to 0.2 mg of purified protein per 1 L of M9ZB medium), b) in aerobic conditions, protein yield was 12× higher when the pASG-IBA35+D1 vector was used (12 mg compared to 0.9 mg of protein of purified protein per 1 L of LB medium).

Optimization of the bacterial strain and medium composition

To select the most optimal E. coli strain and growth conditions, we used pASG-IBA35+D1 vector and aerobic Ni2+ IMAC purification. UV-VIS measurements were carried out immediately after the final purification step (elution from column).

We compared the performance of two strains of E. coli – BL21 (DE3)RILP and DH5α, which originate from different ancestors (B and K12 strain, respectively) and show differences in some metabolic pathways [64]. We tested aerobic and anaerobic conditions and media types. We also analyzed cell growth rate, the yield of purified protein, and Moco retention in the protein. Proteins containing Moco with molybdenum atom have been reported to exhibit a signature absorption peak in the visible range (~450 nm) [65] that is lost during the oxidation of Moco and loss of molybdenum thiolate ligands. The exact absorption peak wavelength depends on the environment of the Moco. For D1anaerobic, we observed a characteristic peak at 410 nm. During the optimization of protein production, we monitored the absorbance at 410 nm as well as the presence of molybdenum by ICP-MS to confirm Moco retention. The list of tested conditions and analysis results are briefly described here and summarized in Supplemental Table 1.

DH5α cells cultured under aerobic conditions in LB medium (DH5αaerobic) reached an OD600 of 0.6 within 3 hours after inoculation and were then induced with AHT. The yield of the purified protein was 5 mg of D1 from a 400 mL culture (Supplemental Fig. S2B), but the protein did not show absorbance at 410 nm and did not contain the molybdenum. When DH5α cells grew under anaerobic conditions in LB medium (DH5αanaerobic-LB), the culture grew slowly and cells reached OD600 of 0.5 after several hours, but they did not grow any further. The yield of purified protein was 0.2 mg from a 400 mL culture (Supplemental Fig. S2B) and there was no detected absorbance at 410 nm. The low amount of the protein did not allow for ICP-MS analysis. When DH5α cells grew under anaerobic conditions using M9ZB minimal medium (DH5αanaerobic-M9ZB) supplemented with NaNO3, the culture reached an OD600 of 0.6 within 4 hours, purified protein absorbed at 410 nm, and molybdenum was detected by ICP-MS. The purification yield was comparable to yields from aerobic cultures (3.4 mg from a 400 mL culture) (Supplemental Fig. S2A).

BL21 (DE3)RILP cells grew well under aerobic conditions in LB medium, the yield of purified protein (4.8 mg/400 mL) was comparable to yield from DH5αaerobic (Supplemental Fig. S3B), and the purified protein did not absorb at 410 nm. Poor growth was observed for BL21 (DE3)RILP cells that grew using NaNO3 as the sole source of electron acceptors in respiratory chain. The cultures did not grow beyond an OD600 of 0.2; consequently, D1 overexpression levels were not tested. We tested an alternative electron acceptor, fumarate, as a negative control. The yield of D1 protein purified from RILP cells that grew using M9ZB medium supplemented with fumarate was 1.2 mg from a 400 mL culture (Supplemental Fig. S3A), but the overexpressed protein did not absorb at 410 nm even if NaNO3 was added just before protein induction with AHT. The molybdenum levels for all samples from BL21 (DE3)RILP were below the detection limits of ICP-MS. There was not enough protein to test samples from BL21 (DE3)RILP cultured anaerobically in the presence of NaNO3 in M9ZB or LB media (Supplemental Table 1).

We concluded that modified M9ZB medium, anaerobic conditions and DH5α cells are suitable for production of D1 protein, showing UV-VIS features of Moco and molybdenum retention. Since there was no significant difference in the amount of protein produced when D1 was overexpressed over-night at 18°C or for 2 hours at 37°C, we decided to follow the 2 hours’ protocol in the later experiments.

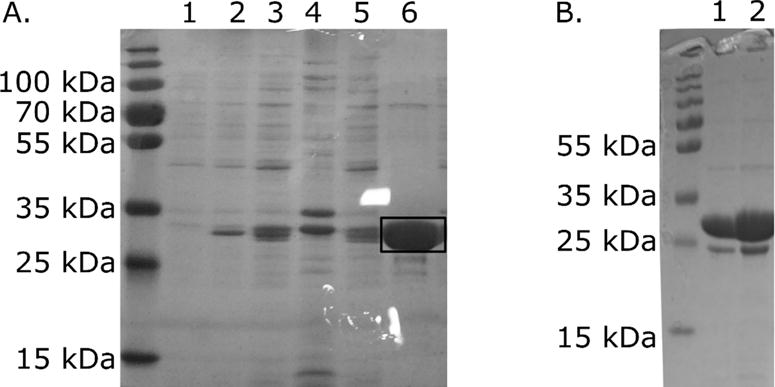

Finally, the purification protocol was optimized to be carried out under anaerobic conditions and resulted in a yield of 5 mg of pure D1 protein from 400 mL M9ZB medium (Fig. 1 AB). For further discussion, we will refer to the protein purified according to this protocol as D1anaerobic. The protein was concentrated to 14 mg/mL and analyzed by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) HPLC-DAD and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) experiments to verify the presence of Moco. Further analysis showed that the protein expressed under aerobic conditions in BL21 (DE3)RILP was free of Moco (Fig. 2A).

Figure 1.

D1anaerobic protein purity. Protein was expressed in DH5α from the pASG-IBA35 vector A. Steps of D1anaerobic purification process. Numbers above the gel mark fractions: 1 – before induction, 2- after induction, 3 – lysate, 4- pellet after centrifugation at 40 000 rcf, 5- NiNTA flow through, 6 – elution (this D1anaerobic protein batch was used for EXAFS experiments). The marked band with mass 30 kDa corresponds to D1 protein. B. The purity of D1anaerobic protein batch used for TSA, crystallization and SEC HPLC analysis (lanes 1 and 2).

Fig. 2.

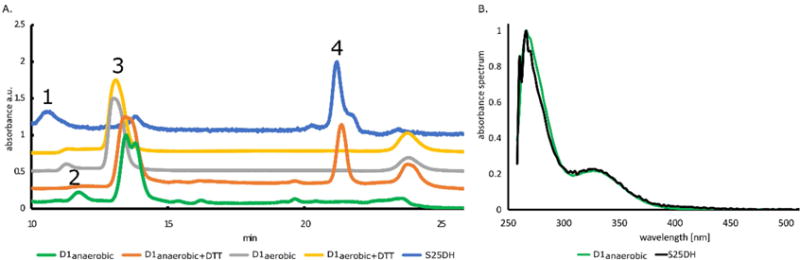

SEC HPLC-DAD analysis of D1anaerobic, D1aerobic and S25DH proteins. A. HPLC elution profile of D1anaerobic (green – without DTT, orange – with DTT), D1aerobic (grey – without DTT, yellow – with DTT) and S25DH (blue). For D1aerobic (green line), three peaks were detected with masses corresponding to 29 kDa and 32 kDa, known as monomeric fractions (peak 3), and 59 kDa, known as dimer (peak 2). For D1anaerobic (grey line), two peaks were detected; dimer (peak 2) and monomer (peak 3). In samples with DTT, there was only a single peak (peak 3) detected with a mass corresponding to 32 kDa (D1anaerobic) or 35 kDa (D1aerobic). B. Absorption spectra of compounds released from analyzed proteins (peak 4). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Size exclusion chromatography with diode array detector (SEC HPLC-DAD)

We used SEC HPLC analysis to check whether the D1anaerobic protein contained Moco. An anaerobically purified native S25DH enzyme [27] was used as a positive control, while D1aerobic served as a negative control. Chromatograms of all samples confirmed the presence of proteins (peaks 1, 2, and 3 Fig. 2A). The detected peak 4 in D1anaerobic and S25DH samples corresponds to a small molecule, as deduced from its retention time (Fig. 2A). The small molecular compound (peak 4) was eluted separately from the D1anaerobic only in the presence of DTT, suggesting the presence of a disulfide bond between this compound and the protein. The absorbance spectra of the compounds present in the S25DH sample and separated from the D1anaerobic sample overlapped with each other (Fig. 2B). This compound was not detected in the D1aerobic sample. D1anaerobic and D1aerobic proteins existed as monomers (~30 kDa), with a small portion of dimeric fraction (~60 kDa). When DTT was present, only the monomeric form of D1 was detected (Fig. 2A).

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy

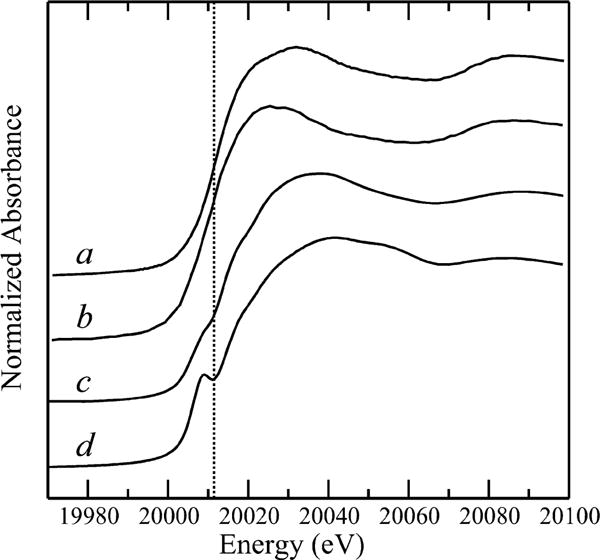

A comparison of the Mo K-edge X-ray absorption near-edge spectra with those of selected Mo enzymes shows clearly distinct near-edge spectra, as shown in Fig. 3. The enzymes for which spectra are shown were selected to represent the diverse coordination environments of molybdenum enzyme systems, a wider range of near-edge spectra are compared in George, G.N., 2017 [60]. Ordinary Mo K-edge XAS spectra have substantial broadening due to the short core-hole lifetime of the Mo 1s level, but nevertheless a careful comparison of features can be informative. One characteristic feature of Mo enzyme near-edge spectra is the 1s→4d “oxo-edge” feature observed in the K-edge spectra of some enzymes. This is best seen for the cis-dioxo Mo(VI) site of sulfite oxidase in Figure 3D. This feature is a formally dipole-forbidden Δl=+2 transition but which gains dipole-allowed Δl=+1 intensity through admixture of p-orbitals through ligand π-bonding [66]. The absence of this feature in the spectrum of the D1 chaperone suggests the absence of Mo=O bonds (Fig. 3). The EXAFS, together with the best fits, are shown in Fig. 4. The EXAFS shows a clear beat around k = 8 Å−1 with two peaks clearly observed in the Fourier transform (Fig. 4B). In agreement with the near-edge spectra, no low-R peak at ~ 1.7 Å characteristic of Mo=O backscattering is observed in the Fourier transform. The transform peaks are primarily typical of Mo—S backscattering at ~2.3 Å with a substantial presence of Mo····Metal backscattering giving rise to the pronounced transform peak at ~2.7 Å. The EXAFS curve-fitting analysis [60, 67] indicates that the EXAFS fits best to three Mo—S at 2.32 Å, with one or two long Mo—O at 2.20 Å. The longer-range metal backscattering fits well to two Mo····Fe, Ni or Cu at 2.72 Å, clearly indicating the unexpected presence of a multi-metallic cluster.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of Mo K-edge X-ray absorption near-edge spectra of the D1 chaperone (a) with Klebsiella pneumoneii nitrogenase MoFe protein (b), oxidized Rhodobacter sphaeroides DMSO reductase (c), and oxidized human sulfite oxidase (d). The vertical broken line is included to guide the eye to relative shifts of the spectra.

Figure 4.

D1 chaperone Mo K-edge EXAFS (solid line) and best fit (broken line) (a) together with the corresponding EXAFS Fourier transforms (phase corrected for Mo—S backscattering) (b). EXAFS curve-fitting gives best fits with a mixed Mo—S/Mo—O first shell coordination with 3 Mo—S at 2.321(3) Å (σ2=0.0044(5)Å2) and 2 Mo—O at 2.21(5) Å (σ2=0.0031(7)Å2) with 2 Mo····Fe at 2.727(2) (σ2=0.0016(3)Å2). We note that 2 Mo····Cu at 2.717(2) (σ2=0.0025(1)Å2) gave an essentially equivalent fit but with a more chemically reasonable value for σ2.

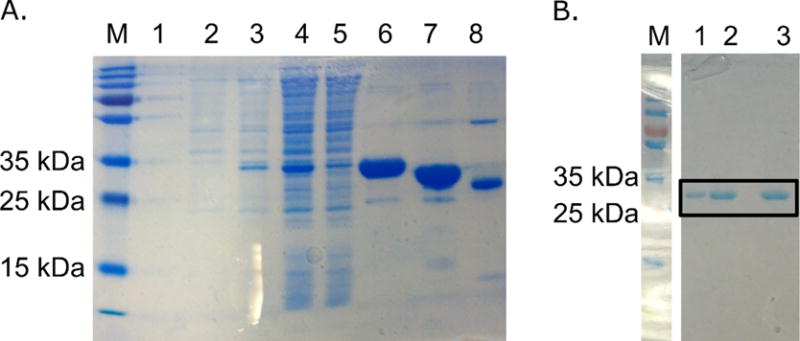

Characterization of D1aerobic – size exclusion chromatography and GDP binding

Having confirmed that D1 protein expressed in a B strain derivative in aerobic conditions does not contain Moco, we decided to use this strain for production of the protein without the cofactor for further analysis. We decided to use a vector with a cleavable N-terminal His-tag, the pMCSG7 vector. BL21(DE3)RILP cells reached an OD600 of 0.8 7 hours after inoculation, and the yield of purified protein was 16 mg from 1 L of TB (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

D1aerobic protein purity. Protein was expressed in BL21(DE3)RILP from pMCSG7+D1 vector. A. Steps of D1aerobic purification process. Numbers above the gel mark fractions: 1 – before induction, 2- after induction, 3 – lysate, 4- pellet after centrifugation at 40 000 rcf, 5- NiNTA flow through, 6 – elution, 7 – D1aerobic digested with rTEV, 8 – rTEV sample. B. The purity of D1aerobic protein after SEC FPLC. This protein batch was used for TSA, ITC, crystallization and SEC FPLC analysis (lanes 1, 2 and 3).

After prolonged exposure of D1aerobic protein to atmospheric air (oxygen), stable oligomeric conglomerates were shown, as verified by SEC. This change in protein oligomerization state was completely reversible upon addition of a reducing agent (DTT) (Fig. 6), thereby supporting the assumption regarding the presence of protein surface cysteines that are prone to oxidation and formation of intermolecular disulfide bridges. SEC fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) elution profiles of D1aerobic protein incubated with DTT indicate the apparent mass of D1aerobic as being between monomer and dimer (45 kDa), while the apparent mass of protein without addition of DTT was between dimer and tetramer (110 kDa) (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

SEC FPLC elution profile of D1aerobic protein. A. Oligomerization of D1aerobic after incubation in aerobic atmosphere. D1aerobic forms oligomers in size of app. 110 kDa (black line) upon prolonged exposure to atmospheric oxygen. This process is reversible after addition of reducing agent (green line), the apparent size of D1aerobic protein is 45 kDa). Normalized data of absorbance at 280 nm are presented.

SEC HPLC analysis of the D1aerobic protein revealed that it did not contain a ligand that could potentially be co-purified with recombinant D1aerobic protein (Fig. 2A). Therefore, D1aerobic samples could be used for binding experiments to check possible interactions with molecules resembling bis-MGD (Moco type) fragments, such as guanosine diphosphate (GDP). The analysis of available crystal structures of a sulfurtransferase, a chaperone protein for a formate dehydrogenase with bound guanosine diphosphate (GDP) (PDB ID: 4PDE) [68], and biochemical studies on a DmsD chaperone protein [69,70] suggested that the GDP or GTP can be used to detect interactions between a chaperone and guanosine nucleotide moiety of MGD (Moco type). Therefore, we used GDP as an MGD surrogate and we checked whether D1aerobic interacts with GDP by thermofluor shift assay (TSA), SEC FPLC and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). There was no significant change in protein stability when TSA measurements were performed using different concentrations of GDP, suggesting a lack of GDP binding to D1aerobic. The differences in recorded melting temperatures for various GDP concentrations were less than 3 °C between each condition, with no correlation between dTm and GDP concentration (Fig. 7A). The lack of interactions between the D1 protein and GDP was additionally confirmed by SEC FPLC (Fig. 7B) and ITC (Fig. 7C). The absorption peak of GDP is 254 nm, but it also absorbs at 280 nm, so the absorption of the complex of GDP and D1 protein should have a slightly higher absorbance measured at 280 nm than that of the D1 protein alone. After adding an excess of GDP, we observed the unbound GDP in late eluting fractions and did not observe a change in absorbance of the D1aerobic sample (Fig. 7B). ITC analysis showed that the addition of GDP to the D1aerobic protein did not generate heat attributable to the binding (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7.

No interaction between chaperone D1 and GDP was detected by thermofluor shift assay (TSA), size exclusion chromatography and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). A. Data from TSA experiments show that the stability of D1aerobic is not affected by GDP. TSA was performed in a presence of decreasing GDP concentrations. Tm of D1aerobic equaled 38 °C. The recorded change of D1aerobic stability in the presence of GDP was less than 3 °C for each condition. B. Data from size exclusion chromatography. The absorbance at 280 nm of D1aerobic protein did not change when GDP was added to the sample indicating that GDP does not interact with a protein. C. Data from ITC experiments of D1aerobic with GDP. The plot presents integrated heat values of each injection. The blank values were subtracted from heat values generated after titration of GDP to D1aerobic. No interaction between D1aerobic and GDP was detected by ITC.

Stability tests and ligand screening by thermofluor shift assay (TSA)

We checked the influence of Moco presence on protein stability and assessed how pH and the presence of ligands affected the melting temperature (Tm) of D1. The respective stabilities of D1aerobic and D1anaerobic proteins were analyzed in a series of buffers (Table 1) based on triple component buffer systems [71] developed for the optimization of protein crystallization. We measured the stability of proteins within a pH range of 6.0–8.0. The D1 protein was most stable at pH ≥ 7.0 for both anaerobic and aerobic samples. One exception was recorded for buffer #1, in which the protein was most stable at pH of 6.0 and 6.5. In some buffers (aerobic #2, #4, #6, Fig. 8 and Table 1), there was a main single transition recorded with a Tm around 40 °C, while for buffer #1 (aerobic), there were at least two main transitions recorded, suggesting two main unfolding (melting) events occurring during sample denaturation.

Fig. 8.

Stability of D1aerobic and D1anaerobic measured by TSA. The numbers from 1 to 7 correspond to different buffers the compositions of which are presented in Table 1. The numbers above each chart correspond to the pH value of a given buffer. Green and orange plots represent recorded Tm values, while red and blue plots the dTm = Tm (D1anaerobic)-Tm (D1aerobic.) (top) or dTm = Tm (D1anaerobic)-Tm (D1anaerobic exposed to air) (bottom). A color scale for each type of plot is presented next to the plot. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The interpretation of the melting curves of the anaerobic samples was not straightforward. Although there was one main transition, the plotted peak (-d(RFU)/dT) was broader than for aerobic samples and its shape suggested that there were several unfolding events occurring at the similar temperature. Overall, both D1aerobic and D1anaerobic proteins were more stable at higher pH values, and pH values below 6.5 were detrimental for protein stability (maximum observed dT of 17°C when the pH changes from pH 6.0 to 8.0 for anaerobic buffer #5). D1aerobic was slightly more stable at lower pH values (pH 6.0) than D1anaerobic while D1anaerobic preferred higher pH (7.5–8.0) than D1aerobic (7.0–7.5).

We also tested the stability of D1anaerobic after overnight exposure to the atmospheric oxygen (Fig. 8). The exposed samples were measured in the same set of buffers covering the pH range between 6.0 and 8.0 (Table 1). The most significant decrease in D1anaerobic stability was observed for buffer #4 at pH 7.5 (dT −3°C), while the most significant increase was observed for buffer #6 at pH 6.0 (dT 4°C). These differences are similar to those between buffers used for measuring D1aerobic. Stability.

In addition to identifying conditions that improve D1 stability, we determined whether particular compounds that may bind to D1 in the absence of Moco stabilize or destabilize D1 protein. We designed a 96-well plate with compounds of various chemical composition, such as nucleotides, purine-based compounds, sugars, antibiotics, metal ions, and amino acids (Table 2). Sugars, purine based ligands, and nucleotides did not affect protein stability; virtually no change in protein melting temperature was observed (less than dT = 3 °C). In the presence of aromatic amino acids (Trp, Tyr, and Phe), there was no transition observed for D1aerobic. Other tested amino acids did not change protein stability (dT less than 3 °C). We observed a significant increase of D1aerobic stability in the presence of zinc (dT = 25 °C), nickel (dT = 12 °C), and cadmium (dT = 12 °C) ions as well as one aminoglycoside antibiotic, streptomycin (dT = 10 °C) (Fig. 9 and Supplemental Fig. S4 AB). For two other aminoglycoside antibiotics, apramycin and paromomycin, two transition states were detected, with the main denaturation event happening around 40 °C and the second, less pronounced event at 55 °C. We observed D1aerobic destabilization in the presence of ammonium molybdate (dT 19 °C) (Fig. 9). There was no transition observed for D1aerobic in the presence of CuCl2, CoCl2, Tris (2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP), FAD, Hepes, 3.5 M urea, or guanidinium hydrochloride (1 M and 3.5 M). Supplemental Fig. S5 presents the results of TSA for all measured compounds that had an influence on Tm of D1aerobic.

Fig. 9.

TSA measurements for ligands. Measurements were done in triplicate; an average value is shown. Tm for the D1 protein is 40°C. All tested compounds are listed in Table 2. Compounds for which it was not possible to calculate Tm or for which the dTm was less than 3°C are not presented on the plot. The list of compounds for which Tms was recorded is presented in Supplemental Fig. S5.

Crystallization trials

The quality and amount of purified D1anaerobic and D1aerobic was sufficient for crystallization trials (Fig. 1B and Fig. 5B). The initial screening using commercial sparse screening kits resulted in the following crystallization conditions for D1aerobic that were further improved by grid optimization: (a) 0.2 M zinc acetate dihydrate, 20% Peg 3350 pH 6.4 (Hampton Research, PegIon, #C2) and (b) 0.2 M MgCl2 hexahydrate, 30% PEG 4000, 0.1 M Tris-HCl pH 8.5 (Hampton Research, Crystal Screen, #A6).

The conditions with magnesium chloride resulted in small crystals (30 μm × 30 μm) diffracting to 9Å (Supplemental Fig. S6). Indexing of the collected data was consistent with a primitive monoclinic lattice, with unit cell parameters a=73, b=180, c=113 and β=102°. Crystals that grew in the presence of zinc ions were too small and fragile for harvesting.

DISCUSSION

Optimizing the recombinant expression of complex and multi-subunit enzymes that rely on diverse cofactors is a daunting task. The process of overexpression of such enzymes in an active form is much more complicated. For example, when proteins such as S25DH are assembled and loaded with a redox cofactor within the cytoplasm, they must be transported through the membrane in a fully folded form to the dedicated periplasmic space [72], which involves tight regulations by specific chaperones for cofactor insertion [15]. Although the protocol for purification of the steroid C25 dehydrogenase from its natural source has been already established [27] and simplified [35], the successful recombinant expression of the S25DH would have a significant impact on the production of sterol-based pharmaceutics. To tackle the multi-subunit, multi-cofactors issue we have adopted a “divide-and-conquer” strategy [73] – the main goal of obtaining the protein with a cofactor was divided into smaller independent steps that were separately solved, leading to the answer of how to obtain the cofactor-loaded chaperone.

In this work, we report an optimized protocol for production of a D1 chaperone protein involved in the maturation of α subunit of S25DH. We have developed protocols for the expression and purification of this protein loaded with Moco and without Moco depending on the growth conditions, system for protein overexpression and E. coli bacterial strain. These two protocols allow others to choose a method to produce the soluble and pure recombinant chaperone protein suitable for further protein-based studies or applications. The resulting amount of purified protein is sufficient for biochemical and biophysical studies, including procedures in which protein without a cofactor may be needed, such as binding assays, antibody production, structural characterization, and protein stability assays.

Determination of the Moco presence in D1 protein

One of our main goals in this study was to increase D1 yield. Using the 6xHis-tagged construct instead of the Strep-tagged construct resulted in an improvement in the amount of produced protein. Doing so may have influenced D1 mRNA performance during protein synthesis or introduced positive changes in protein conformation, thereby diminishing D1’s aggregation. The observed higher yield may have also resulted from a greater binding capacity of NiNTA resin than that of Strep-Tactin resin. This difference was also noted in the manufacturers’ manuals. Additionally, because Strep-Tactin is a protein-based resin, it loses its capacity and stability over time. This decrease in resin performance may also lead to incomplete binding of a protein to the Strep-Tactin (Supplemental Fig. S7) resin that also results in an observed lower yield of purified Strep-tagged protein. We did not observe a significant decrease in the performance of resin composed of nitrilotriacetic (NTA) acid, which is a component of NiNTA resins. We used immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) for D1 purification, as the differences in genetic construct and type of purification resin resulted in 20× better protein yield. E. coli native proteins that nonspecifically interact with NiNTA resin [74,75] were removed from the purified protein sample by SEC (Fig. 5B).

Next, we focused on optimizing a protocol for the production of D1 protein loaded with Moco. We tested E. coli strain, medium type, and culture growth conditions. We checked two E. coli strains of different ancestry, DH5α (K12 strain derivative) and BL21 (DE3)RILP (B strain derivative). Although DH5α cells are typically used for plasmid amplification rather than for protein production, DH5α cells produced D1 loaded with Moco when cultured anaerobically on M9ZB minimal media supplemented with molybdenum sulfate and NaNO3. Supplementation with NaNO3 under anaerobic conditions was especially crucial because NaNO3 is a very effective inducer of the expression of a molybdoenzyme, nitrate reductase. Because the nitrate reductase production is induced, all metabolic pathways involved in molybdenum cofactor synthesis are active. Therefore, the subsequent induction of D1 chaperone protein overexpression by AHT was conducted in an environment satisfying the conditions for cofactor synthesis [76,77].

The BL21 (DE3)RILP strain was not able to produce large amounts of the protein loaded with Moco; this may be due to metabolic differences between DH5α and BL21 (DE3)RILP [64]. All descendants of E. coli B type cells lack the fnr gene [64]. Fumarate-nitrate regulator (FNR) directly or indirectly regulates, as a transcriptional regulator, the expression of a very large number of genes and operons and controls many aspects of metalloprotein biosynthesis in E. coli[78]. Additionally, due to the lack of the modE gene, BL21 cells also demonstrate impaired molybdenum transport activity [64]. ModE is a molybdenum-responsive transcriptional regulator that also acts as an enhancer of the expression of genes coding for molybdoenzymes, both directly and indirectly [79]. Inefficient Moco production in BL21 (DE3)RILP allowed us to develop and optimize protocols for the production of Moco-free protein for biochemical or biophysical studies.

Analysis of the D1anaerobic sample suggests the presence of the same type of cofactor as in S25DH. The presence of the bis-MGD type of Moco in S25DH is predicted based on similarity to other proteins of the DMSO reductase family. SEC HPLC analysis shows that the absorption spectra of cofactors isolated from D1anaerobic and S25DH protein were identical with a comparable retention time (Fig. 2B). EXAFS analysis confirmed the presence of molybdenum and sulfur atoms (Mo-S) environment indicating presence of molybdenum cofactor in D1anaerobic. The EXAFS analysis shows that the molybdenum coordinates three sulfurs (Fig. 4). As D1 has only two cysteines and exists in monomeric form, it is likely that at least one dithiolate ligand of Moco is coordinated by the molybdenum atom. The third sulfur may come either from the protein or from a second dithiolate (in the case of the bis-MGD type of Moco). Because the cofactor dissociates from D1anaerobic under denaturing conditions only after the addition of DTT (Fig. 2B), and mature enzymes from the DMSO reductase family contain bis-MGD, these data may be explained by a model in which bis-MGD is covalently attached to D1anaerobic by a disulfide bond in our D1anaerobic samples. It is unclear whether this covalent attachment is of biological relevance, as the EXAFS results indicated unexpected Mo····(Cu,Ni,Fe) interactions. D1anaerobic could contain nickel ions due to the adopted purification strategy, and the presence of Ni2+ may explain the observed EXAFS spectra. The nickel ions may form Mo-Ni-S clusters similar to Mo-Cu-S clusters observed in copper poisoning [80] and possibly affect the interaction between D1anaerobic and bis-MGD. Such Mo-Ni-Cu clusters are known in small molecule literature [81] and have also been reported in complexes containing Mo bound with a dithiolene ligand [82].

Effectively, we have demonstrated that an anaerobic environment and NaNO3 supplementation are necessary for efficient production of recombinant protein containing Moco and that the E. coli produced Moco/MGD can be incorporated into D1 chaperone.

Biochemical characterization of Moco-free D1 chaperone

The protocols for anaerobic and aerobic expression and purification of D1 were efficient enough to carry out experiments to determine protein stability, oligomerization state, and binding propensity for various ligands. When working with protein overproduction, efforts are often directed toward optimizing conditions that prevent protein aggregation and degradation.

We determined conditions that stabilized the protein. The protein was most stable at pH higher than 7.0, and D1anaerobic preferred a pH higher than that preferred by D1aerobic. D1aerobic was most stable in buffer #1 at pH 6.0 and 6.5, suggesting that the interactions between buffer components and D1aerobic changed the pH stability profile of the protein or that the protein-buffer component complex formed at a lower pH (Fig. 8).

The differences in thermal stability between D1anaerobic and D1aerobic are buffer-dependent. At the optimal pH, D1anaerobic was more stable than D1aerobic in buffers #3, #5, and #6, while D1aerobic was more stable in buffers #1, #2, #4, and #7. The variability of Tm in different conditions but with the same pH value is higher for D1aerobic than for D1anaerobic suggesting that the D1aerobic is more affected by the buffer components, presumably due to the formation of protein-buffer complexes in lieu of the cofactor. D1anaerobic incubated overnight at atmospheric air (and presumably with oxidized, partially decomposed Moco) did not show any major changes in its Tm (less than dT = 4 °C) (Fig. 8), which suggests either relative stability of Moco when bound to D1 protein or efficient stabilization of the protein by Moco degradation products (Fig. 8).

The D1aerobic protein was well stabilized by streptomycin as well as chloride salts of some divalent metal ions, e.g., ZnCl2, NiCl2, and CdCl2 (Fig. 9 and Supplemental Fig. S4A). The influence of zinc ions on D1aerobic was also noticed in crystallization experiments, as crystals were formed in conditions with zinc salts. Metals are known to affect protein thermal stability and shape because residues that bind metal often undergo conformational changes upon metal binding [83]. Histidines, cysteines, glutamic acid, and aspartic acid most commonly bind to metal ions [84], and metal binding proteins quite often possess characteristic motifs of interaction. Comparative analyses of crystal structures in the PDB revealed that zinc and nickel most often bind cysteines or histidines [84]. D1 has 7 histidines and 2 cysteines so there are possible sites of interactions. The mode of stabilization, however, needs to be determined since no common metal binding motifs were detected by several servers predicting metal binding sites in protein: IonCom [85], SeqChed [86], ZincExplorer [87] (results not shown). Coincidentally, as EXAFS analysis demonstrated that molybdenum in D1anaerobic formed Mo-Ni clusters, it is possible that the binding site for divalent transition metals in D1 overlaps with the Moco binding site.

Streptomycin was another compound that stabilized D1 protein (Fig. 9). It is a branched molecule with two guanidinium groups close to each other, resembling a set of two arginines. An RR sequence is a motif characteristic of a twin arginine system (TAT). This motif is recognized by the translocation system and its recognition is blocked by the chaperone until the transported protein matures [32]. It has been shown that other molybdoenzyme maturation chaperones recognize the TAT signal motif directly [88,89]. Two arginines present in the N-terminal fragment of metalloproteins are recognized by a chaperone molecule, and the protein is then transported through a membrane. It is likely that the streptomycin’s guanidinium groups are recognized in a similar way to arginines and that interaction stabilizes the D1 chaperone. No change in D1aerobic stability was observed in the presence of arginine by TSA. We used the streptomycin to carry out the crystallization screens, but we did not observe the improvement on D1 crystallizability.

There was no change in the fluorescence signal when D1aerobic was incubated with 3.5 M urea, FAD, 1 M and 3.5 M guanidine, CoCl2, or CuCl2, indicating that the protein may have denatured upon mixing with these compounds before the actual measurements. For TCEP, a Tm of around 20°C was recorded, suggesting strong destabilization effects of this reducing compound on D1aerobic (Supplemental Fig. S5).

Our crystallization trials resulted in several conditions in which crystals were formed (Supplemental Fig. S6). Each of the promising conditions were optimized, but unfortunately, we were unsuccessful at this point in obtaining crystals diffracting better than 9 Å. There are several potential reasons why the protein may not form crystals of a quality suitable for successful structure determination. The protein may have a high degree of structural flexibility, and it is possible that the sample may not be homogenous. In FPLC analysis, we observed that D1aerobic changes its oligomerization state upon exposure to oxygen, which is reversible by the addition of a reducing agent, indicating intramolecular disulfide bridge formation. Although the influence of reducing agents on crystallization experiments was tested, it did not improve the quality of crystals. It is possible that during crystallization, the reducing agent oxidized leading to the oxidation of protein cysteines, subsequent formation of disulfide bridges, and consequently protein oligomerization. SEC FPLC in non-denaturing conditions showed a higher apparent mass of both the monomer and dimer than the mass calculated from the sequence (Fig. 6), while the results from SEC HPLC in denaturing conditions agreed with the masses calculated for the monomer and dimer (Fig. 2A). The SEC analysis suggests the elongated shape of the protein or partial disorder because deviation from the globular shape affects elution time [90]. High protein disorder usually correlates with poor protein crystallizability [91,92].

Several previous studies showed that GDP can act as a Moco surrogate in Moco-free proteins [68]. The surface signature consistent with the guanine binding site has been also detected in the structure of a D1 homolog [70]. Because the HPLC analysis indicated that D1aerobic was not bound to any UV-VIS absorbing molecule (Fig. 2A), we were interested in determining whether GDP could act as a Moco surrogate. We ran several experiments to detect this putative interaction: simple SEC analysis under native conditions, ITC, and TSA. Addition of the GDP to the protein sample did not change its absorbance at 280 nm (Fig. 7B), indicating that no additional molecule was bound to the protein. No heat of binding was detected when titrating D1aerobic with the GDP using ITC (Fig. 7C), and protein thermal stability of D1aerobic was not affected when GDP was added (Fig. 7A). These results suggest that D1aerobic does not bind Moco/MGD through the nucleoside fragment alone.

CONCLUSIONS

An efficient system for molybdenum cofactor production would positively impact analytical, biochemical, and pharmaceutical studies. We developed efficient methods for production and purification of chaperone proteins containing Moco, which would provide a precursor source of Moco and a high amount of protein for further analysis. The EXAFS and TSA results described here provide background for further studies on Moco cofactor assembly and chaperone functions. The optimized method for anaerobic chaperone production presented here was necessary and crucial to develop the system for overexpression of active steroid C25 dehydrogenase (Rugor et al., to be published), validating our divide-and-conquer strategy.

Suggested future directions include development of methods for isolation of Moco from recombinant D1 protein. The purified D1anaerobic protein loaded with Moco can serve as a natural source of the cofactor for further chemical modifications that may be easily separated from a protein under reducing conditions. Overexpression of the chaperone protein alone guarantees that the extracted Moco is not contaminated with other cofactors present in more complex molybdoenzymes. Moreover, the D1 protein can also be used for Moco stabilization by binding to it under various conditions. Future plans may also include further trials in the structure determination to gain more insight into the process of maturation of cofactor-containing multi-subunit proteins.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

S25DH chaperone D1 has been purified in aerobic and anaerobic conditions

Molybdenum cofactor (Moco) presence in D1 was confirmed by EXAFS and HPLC analysis

D1 protein has been characterized by Thermofluor Shift Assay

Buffer conditions and small molecules that stabilize D1 have been identified

Methods of selection between Moco-free and Moco-loaded protein are presented

Acknowledgments

We thank Przemyslaw J. Porebski and Barat Venkataramany for valuable comments and for critical reading of the manuscript. This research was possible through funding from the Marian Smoluchowski Krakow Research Consortium – a Leading National Research Centre KNOW supported by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education. E.N. was supported by the Foundation for Polish Science. E.N., A.R., and M.S. acknowledge the financial support of the Polish institutions: National Centre for Research and Development [grant number LIDER/33/147/L-3/11/NCBR] and National Science Centre [grant number 2012/05/D/ST4/00277]. W.M. and M.P.C. acknowledge the financial support of the National Institutes of Health [grant number R01GM117325]. Research at the University of Saskatchewan was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, with other support from a Canada Research Chair (G.N.G.), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), and the Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation (SHRF). Portions of this research were carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, a Directorate of SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science by Stanford University. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program (P41RR001209).

Abbreviations

- Moco

molybdenum cofactor

- TSA

thermofluor shift assay

- EXAFS

extended X-ray absorption fine structure

- SEC

size exclusion chromatography

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- FPLC

fast protein liquid chromatography

- ICP-MS

inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry

- bis-MGD

bis-molybdopterin guanine dinucleotide

- S25DH

steroid C25 dehydrogenase

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

- GDP

guanosine diphosphate

- DTT

dithiothreitol

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Kniemeyer O, Heider J. Ethylbenzene dehydrogenase, a novel hydrocarbon-oxidizing molybdenum/iron-sulfur/heme enzyme. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:21381–21386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101679200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leimkuhler S, Iobbi-Nivol C. Bacterial molybdoenzymes: old enzymes for new purposes. FEMS microbiology reviews. 2016;40:1–18. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuv043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nilsson T, Rova M, Smedja Backlund A. Microbial metabolism of oxochlorates: a bioenergetic perspective. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1827:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saltikov CW, Newman DK. Genetic identification of a respiratory arsenate reductase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:10983–10988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834303100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng C, Tollin G, Enemark JH. Sulfite oxidizing enzymes. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2007;1774:527–539. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hofmann NR. Opposing Functions for Plant Xanthine Dehydrogenase in Response to Powdery Mildew Infection: Production and Scavenging of Reactive Oxygen Species. The Plant cell. 2016;28:1001. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mendel RR, Hansch R. Molybdoenzymes and molybdenum cofactor in plants. Journal of experimental botany. 2002;53:1689–1698. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erf038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishino T, Okamoto K, Eger BT, Pai EF, Nishino T. Mammalian xanthine oxidoreductase – mechanism of transition from xanthine dehydrogenase to xanthine oxidase. The FEBS journal. 2008;275:3278–3289. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajagopalan KV. Molybdenum: an essential trace element in human nutrition. Annual review of nutrition. 1988;8:401–427. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.08.070188.002153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krompholz N, Krischkowski C, Reichmann D, Garbe-Schonberg D, Mendel RR, Bittner F, Clement B, Havemeyer A. The mitochondrial Amidoxime Reducing Component (mARC) is involved in detoxification of N-hydroxylated base analogues. Chemical research in toxicology. 2012;25:2443–2450. doi: 10.1021/tx300298m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ott G, Havemeyer A, Clement B. The mammalian molybdenum enzymes of mARC. Journal of biological inorganic chemistry : JBIC : a publication of the Society of Biological Inorganic Chemistry. 2015;20:265–275. doi: 10.1007/s00775-014-1216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaiser BN, Gridley KL, Ngaire Brady J, Phillips T, Tyerman SD. The role of molybdenum in agricultural plant production. Annals of botany. 2005;96:745–754. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warnke M, Jung T, Dermer J, Hipp K, Jehmlich N, von Bergen M, Ferlaino S, Fries A, Muller M, Boll M. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 Synthesis by Enzymatic Steroid Side-Chain Hydroxylation with Water. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55:1881–1884. doi: 10.1002/anie.201510331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zdunek-Zastocka E, Lips HS. Plant molybdoenzymes and their response to stress. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum. 2003;25:437–452. doi: 10.1007/s11738-003-0026-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mendel RR, Leimkuhler S. The biosynthesis of the molybdenum cofactors. Journal of biological inorganic chemistry : JBIC : a publication of the Society of Biological Inorganic Chemistry. 2015;20:337–347. doi: 10.1007/s00775-014-1173-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leimkuhler S, Wuebbens MM, Rajagopalan KV. The History of the Discovery of the Molybdenum Cofactor and Novel Aspects of its Biosynthesis in Bacteria. Coordination chemistry reviews. 2011;255:1129–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leimkuhler S. The Biosynthesis of the Molybdenum Cofactor in Escherichia coli and Its Connection to FeS Cluster Assembly and the Thiolation of tRNA. Advances in Biology. 2014;2014:21. doi: 10.1155/2014/808569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nichols JD, Rajagopalan KV. In vitro molybdenum ligation to molybdopterin using purified components. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:7817–7822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413783200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hille R. The Mononuclear Molybdenum Enzymes. Chemical reviews. 1996;96:2757–2816. doi: 10.1021/cr950061t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]