Abstract

Purpose Targeting of the PD-1/PD-L1 signalling pathway is a promising treatment strategy in several cancers. The aim of this study was to assess the expression of PD-L1 on tumour cells and tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in gastric cancer (GC) and its prognostic impact.

Materials and Methods A total of 240 patients who were diagnosed with GC at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre (SYSUCC) from May 2008 to December 2013 were included in this study. PD-L1 expression was detected by immunohistochemistry (IHC) in all GC tumour specimens. The Cox proportional hazard regression model was used to assess the association between PD-L1 expression and overall survival (OS).

Results The positive rates of PD-L1 expression on tumour cells and TILs were 74.8% and 65.8%, respectively. Patients with poor tumour differentiation had higher positive rates of PD-L1 expression on tumour cells (p=0.023). There was no significant association between PD-L1 expression on tumour cells and other clinicopathological data. In TILs, PD-L1 expression was significantly higher in patients who underwent surgery (p=0.031) and were in the late stage (p=0.021) than those without surgery and in the early stage. Patients with positive PD-L1 expression on TILs had a significantly shorter five-year OS than those with negative PD-L1 expression (14.2 vs 18.3; p=0.001); therefore, PD-L1 expression on TILs is an independent prognostic factor. However, PD-L1 expression on tumour cells is not associated with OS (p=0.945).

Conclusion Our findings suggest that PD-L1 expression on TILs may be a predictive factor for immunotherapy of PD-1/PD-L1 pathway inhibitors.

Keywords: gastric cancer, PD-L1, TILs.

Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fourth most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide 1. For GC patients in the early stage, surgery is the curative treatment. Conventional treatment modalities such as surgery combined with chemotherapy or chemo-radiotherapy do not achieve good prognosis of advanced-stage GC 2. Although new chemotherapeutic agents have improved response rates compared with previous chemotherapeutic regimens, the five-year survival rate of patients with advanced GC is still only 20-30% 3. Thus, new therapeutic strategies are urgently needed.

Recent clinical trials targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 signalling pathway using monoclonal antibodies have yielded promising results in several cancers 4-7. Preliminary results regarding PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in patients with metastatic GC are also promising, and phase III studies have already begun 8. Previous studies have reported that PD-L1 is expressed on different tumour types including GC, and its expression on tumours or tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) is correlated with clinicopathological features and survival 9-12.

In this study, we examined PD-L1 expression on tumours and TILs in patients with GC and its correlation with clinicopathological variables as well as overall survival (OS) to determine the prognosis and predictive value of PD-L1 expression on GC, and which patients may benefit from agents targeting PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors.

Patients and Methods

Patients

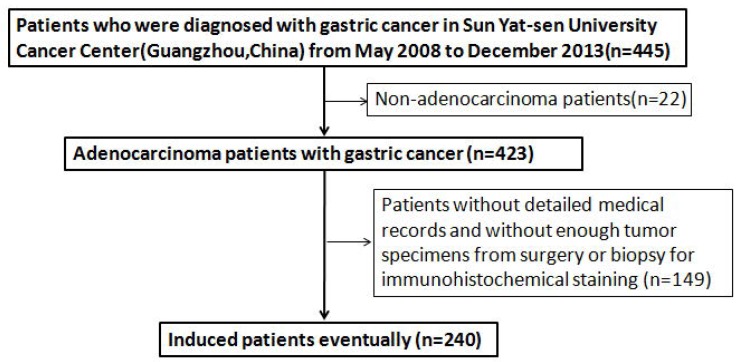

A total of 240 patients who were diagnosed with GC at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre (SYSUCC) from May 2008 to December 2013 were screened for eligibility. Patients were included only if they met both of the following criteria: 1) the pathological tumour type was adenocarcinoma; and 2) the patient had detailed medical records and sufficient tumour specimens from surgery or biopsy for immunohistochemical staining of PD-L1. Figure 1 summarises the process of patient enrolment. The clinicopathological features included age, gender, stage, differentiation, tumour location, and surgery status. Clinical stage was determined according to the tumour-node-metastasis (TNM) classification of the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)/International Union against Cancer (UICC) staging system. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of SYSUCC. All patients provided written informed consent before sample collection.

Figure 1.

Flowing chart of the enrollment

Immunohistochemical analysis

PD-L1 expression on human GC specimens was assessed by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining using a rabbit monoclonal anti-human antibody (E1L3N™, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA; 1:75). Sections (5-µm thickness) were cut from the formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumour block and routinely deparaffinised and rehydrated. For antigen retrieval, slides were heated in a microwave oven for 30 min in citrate buffer solution (pH=7.4) and cooled slowly to room temperature for 20 min. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 8 min. Sections were then incubated with the anti-PD-L1 antibody overnight (> 12 h). Slides were subsequently rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) three times and incubated with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies. After incubation, slides were washed again with PBS and visualised using diaminobenzidine. Mayer's haematoxylin was used to counterstain the sections, which were dehydrated and mounted.

Two pathologists blinded to the patients' information independently assessed the expression of PD-L1. The semi-quantitative H-score (maximum value of 300 corresponding to 100% of tumour cells positive for PD-L1 with an overall staining intensity score of 3) was calculated by multiplying the percentage of stained cells by an intensity score (0, absent; 1, weak; 2, moderate; and 3, strong). Cases with greater than 10% PD-L1 expression on tumour cells were considered positive. PD-L1 expression was also detected on TILs in the same manner.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, NY). Pearson's chi-squared or Fisher's exact tests were used to assess correlations between PD-L1 expression and clinicopathological variables. The Kaplan-Meier test was used to generate the OS curves and the log-rank test was used to evaluate differences in OS. Univariate and multivariate analyses of prognostic factors were performed using the Cox proportional hazard regression model. A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 240 patients with GC were included in this study. The clinicopathological features of the enrolled patients are shown in Table 1. The mean age of all patients at diagnosis was 59.1 (range: 24-85) years; 72 (30%) were female and 168 (70%) were male. According to UICC/AJCC, the number of patients diagnosed at Ⅰ/Ⅱ(early stage) and Ⅲ/Ⅳ(late stage) were 44 (18.3%) and 196 (81.7%), respectively. Tumour differentiation was classified as follows: poor, 170 (70.8%); well, 70 (29.2%). Tumour location was classified as follows: proximal, 74 (30.8%); remote, 87 (36.3%); body, 52 (21.7%); and other, 27 (11.3%). Of the 240 patients in the cohort, 41(17.1%) underwent surgery.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for 240 Patients with gastric cancer

| Characteristics | All cohort | |

|---|---|---|

| N0. | % | |

| No. of patients | 240 | 100 |

| Age(years) | ||

| ≤59.1 | 120 | 50 |

| >59.1 | 120 | 50 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 72 | 30 |

| Male | 168 | 70 |

| T-stage | ||

| 1 | 6 | 2.5 |

| 2 | 14 | 5.8 |

| 3 | 115 | 47.9 |

| 4 | 105 | 43.8 |

| N-stage | ||

| 0 | 22 | 9.2 |

| 1 | 51 | 21.3 |

| 2 | 67 | 27.9 |

| 3 | 100 | 41.7 |

| M-stage | ||

| 0 | 180 | 75 |

| 1 | 60 | 25 |

| Stage | ||

| Ⅰ-Ⅱ | 44 | 18.3 |

| Ⅲ-Ⅳ | 196 | 81.7 |

| Differentiation | ||

| poor | 170 | 70.8 |

| well | 70 | 29.2 |

| Tumor location | ||

| Proximal | 74 | 30.8 |

| Remote | 87 | 36.3 |

| Body | 52 | 21.7 |

| Other | 27 | 11.3 |

| Surgery | ||

| No | 41 | 17.1 |

| Yes | 199 | 82.9 |

PD-L1 expression on tumour cells and TILs

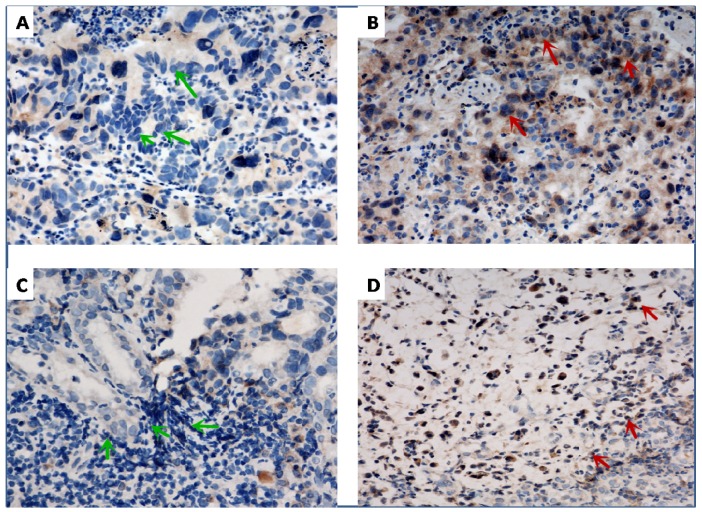

Representative PD-L1 staining is shown in Figure 2. The status of PD-L1 expression (presented by the H-score) is shown in Table 2. With regard to tumour cells, PD-L1 expression was negative in 62 (25.8%) patients and positive in 178 (74.2%) patients. With regard to TILs, PD-L1 expression was negative in 82 patients (34.2%) and positive in 158 patients (65.8%).

Figure 2.

Representative of immunohistochemical staining for programmed cell death-ligand-1 (PD-L1) in gastric cancer. Negative (A, green arrow) and positive (B, red arrow) PD-L1 expression on tumor cells, respectively. Negative (C, green arrow) and positive (D, red arrow) PD-L1 expression in TILs, respectively. ×400 magnification.

Table 2.

The expression of PD-L1 in Patients with gastric cancer

| PD-L1 expression | All cohort | |

|---|---|---|

| N0. | % | |

| On tumor cells | ||

| negative | 62 | 25.8 |

| positive | 178 | 74.2 |

| On TILs | ||

| negative | 82 | 34.2 |

| positive | 158 | 65.8 |

Correlations between patient characteristics and PD-L1 expression

We explored correlations between patient characteristics and the expression of PD-L1 on tumour cells and TILs. As shown in Table 3, patients with poor tumour differentiation had a higher positive rate of PD-L1 expression on tumour cells (p=0.023). There was no significant association between PD-L1 expression on tumour cells and other clinicopathological data, including age (p=0.184), gender (p=1.000), stage (p=0.849), surgery (p=0.337), or tumour location (p=0.881). In TILs, as shown in Table 4, PD-L1 expression was significantly higher in patients who underwent surgery (p=0.031) and were in the late stage (p=0.021) than in those without surgery and in the early stage. However, no significant difference was observed between PD-L1 expression on TILs and other clinicopathological variables, including age (p=0.683), gender (p=0.767), differentiation (p=0.455), or tumour location (p=0.413).

Table 3.

The correlation between PD-L1 expression on tumor and clinicopathological features of patients with GS

| Characteristics | N | PD-L1 negative, N (%) | PD-L1 positive, N (%) | X2 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 62 (25.8) | 178 (74.2) | |||

| Age, years | |||||

| <59 | 36 (58.1) | 84 (47.2) | |||

| ≥59 | 26 (41.9) | 94 (52.8) | 2.175 | 0.184 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 19 (30.6) | 53 (29.8) | |||

| Male | 43 (69.4) | 125 (70.2) | 0.017 | 1.000 | |

| Stage | |||||

| Ⅰ-Ⅱ | 12 (19.4) | 32 (18.0) | |||

| Ⅲ-Ⅳ | 50 (80.6) | 146 (82.0) | 0.058 | 0.849 | |

| Differentiation | |||||

| Poor | 51 (82.3) | 119 (66.9) | |||

| Well | 11 (17.7) | 59 (33.1) | 5.281 | 0.023 | |

| Surgery | |||||

| Yes | 54 (87.1) | 145(81.5) | |||

| No | 8 (12.9) | 33(18.5) | 1.031 | 0.337 | |

| Tumor location | |||||

| Proximal | 18 (29.0) | 56 (31.5) | |||

| Remote | 21 (33.9) | 66 (37.1) | |||

| Body | 15 (24.2) | 37 (20.8) | |||

| other | 8 (12.9) | 19 (10.7) | 0.668 | 0.881 |

Table 4.

The correlation between PD-L1 expression on TILs and clinicopathological features of patients with GS

| Characteristics | N | PD-L1 negative, N (%) | PD-L1 positive, N (%) | X2 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 63 (43.7) | 81 (56.3) | |||

| Ages, years | |||||

| <59 | 43 (52.4) | 77 (48.7) | |||

| ≥59 | 39 (47.6) | 81 (51.3) | 0.296 | 0.683 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 26 (31.7) | 46 (29.1) | |||

| Male | 56 (68.3) | 112 (70.9) | 0.173 | 0.767 | |

| Stage | |||||

| Ⅰ-Ⅱ | 22(26.8) | 22(13.9) | |||

| Ⅲ-Ⅳ | 60 (73.2) | 136 (86.1) | 6.005 | 0.021 | |

| Differentiation | |||||

| Poor | 61 (74.4) | 109 (69) | |||

| Well | 21 (25.6) | 49 (31) | 0.763 | 0.455 | |

| Surgery | |||||

| Yes | 74 (90.2) | 125 (79.1) | |||

| No | 8 (9.8) | 33 (20.9) | 4.721 | 0.031 | |

| Tumor location | |||||

| Proximal | 23 (28) | 51 (32.3) | |||

| Remote | 32 (39) | 55 (34.8) | |||

| Body | 18 (22) | 34 (21.5) | |||

| other | 9 (11) | 18 (11.4) | 0.591 | 0.901 |

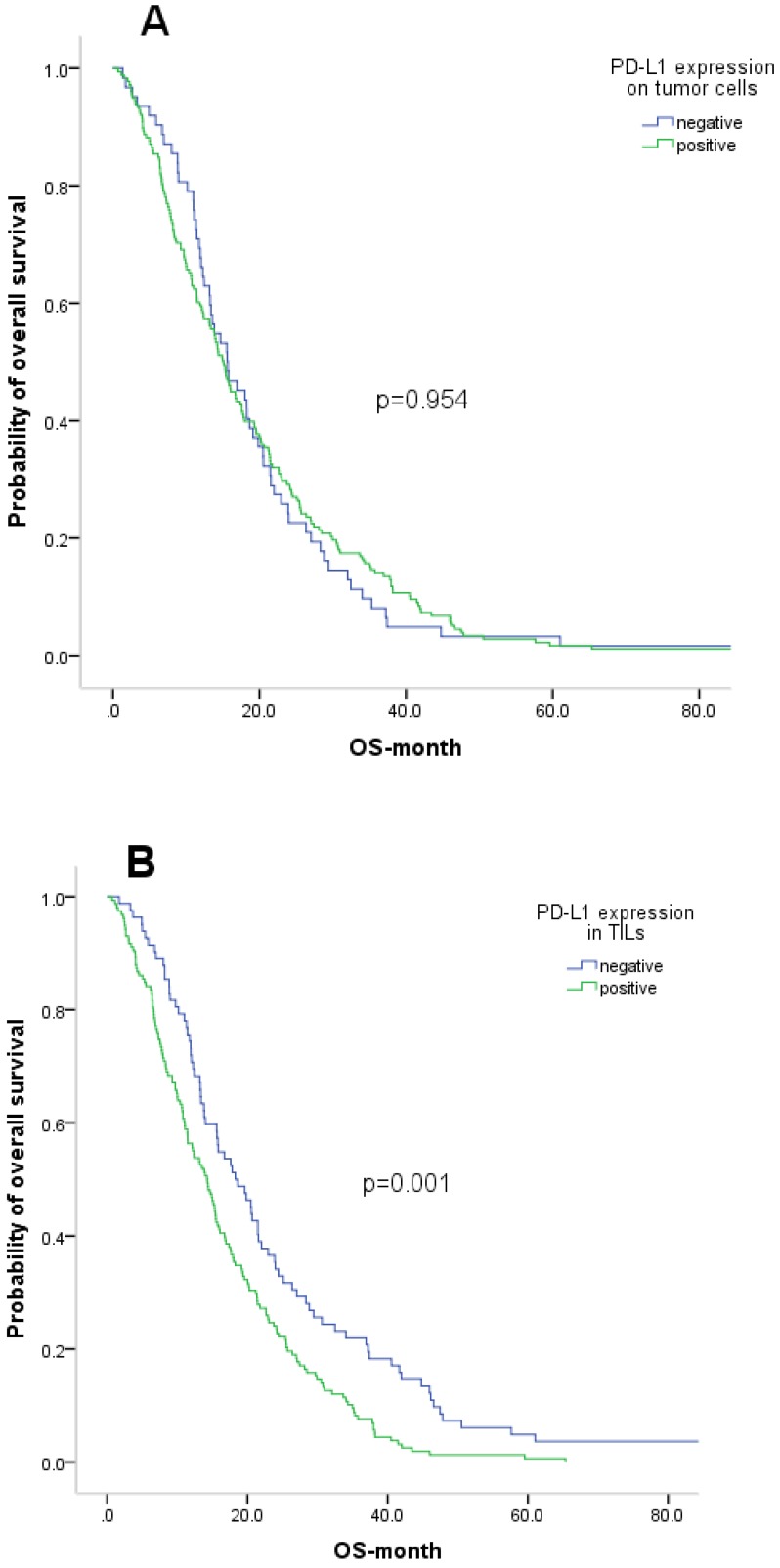

Survival estimates for PD-L1 expression and other variables

We also evaluated the prognostic value of PD-L1 expression and other clinicopathological features. At the time of analysis, all 240 patients were deceased. The median OS of the patient cohort was 15.3 months. OS according to PD-L1 expression on tumour cells and TILs is shown by Kaplan-Meier curves in Figure 3. Patients with positive PD-L1 expression on TILs had a significantly shorter five-year OS than those with negative PD-L1 expression (14.2 vs 18.3; p=0.001). However, PD-L1 expression on tumour cells was not associated with OS (p=0.945). Additionally, late stage and no surgery were significantly correlated with poor survival.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curve analysis of overall survival (OS) in gastric cancer patients. A. Correlation between PD-L1 expression on tumor cells and OS. B. Correlation between PD-L1 expression on TILs and OS

The Cox proportional hazards model was applied to identify the independent prognostic effects of the clinicopathological variables and PD-L1 expression. PD-L1 expression on TILs was identified as an independent predictive factor for OS (p=0.005). Surgery was also identified as an independent predictor for OS (p<0.001).

Discussion

In the current study, we assessed the level of PD-L1 expression on tumour cells and TILs and its association with OS in GC patients. We found that PD-L1 is not only expressed on tumour cells, but is also expressed on TILs at a high rate (65.8%). PD-L1 expression on tumour cells is not correlated with OS. However, PD-L1 expression on TILs is significantly associated with OS and is an independent prognostic factor. To our knowledge, this is the first report to show that high levels of PD-L1 expression on TILs are correlated with poorer OS in GC. We also determined the association between PD-L1 expression on tumour cells and TILs with clinicopathological features.

Agents used to target the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway have recently been reported to exert promising clinical benefits in several advanced cancers 4-7. High PD-L1 expression on tumour cells is associated with prognosis in several malignancies 13-15. We found that PD-L1 was expressed in 74.2% of patients with GC, consistent with a previous study that reported a positive rate of PD-L1 expression in 50.8% of 132 GC patients 16. The effect of PD-L1 expression on prognosis remains controversial. In our study, we did not observe a correlation between PD-L1 expression and OS on tumor cells. The same conclusion was reported by Tatsuro Tamura 12. However, some papers showed that positive PD-L1 expression on tumour cells is associated with a shorter OS in GC patients 17-20. In other report, GC patients with positive PD-L1 expression on tumour cells had a significantly improved OS 21. In Eto`s report 17, the patients with II/III stage GC were enrolled. However, in our study, we not only enrolled patients with II/III GC, but also the cohort with I/IV GC. Other reasons might contribute to the difference of the present and previous studies: small number of patients enrolled, different antibodies used to detect PD-L1 and no universal standard for PD-L1 expression. Further studies are needed to reveal the precise mechanism of PD-L1 up-regulation in GC.

In a series of clinical trials using PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, PD-L1 expression on tumour cells was identified as a biomarker to predict patient response to anti-PD-1 therapy. However, patients with negative PD-L1 expression on tumour cells also respond to anti-PD-L1 therapy. Thus, new predictive biomarkers targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is urgently needed. PD-L1 is expressed not only on tumour cells but also on TILs. Activated T cells secrete cytokines such as interferon-γ, which can induce PD-L1 expression on the tumour microenvironment, including tumour cells and TILs. Our current study revealed that positive PD-L1 expression on TILs was present in more than half of all GC patients examined, which was supported by a previous study in which PD-L1 was determined to be expressed on tumour-infiltrating mononuclear cells in 58 of 143 patients with urothelial carcinoma 11. Moreover, our current data provide evidence that positive PD-L1 expression on TILs is statistically correlated with poorer OS. Importantly, PD-L1 expression on TILs, but not tumour cells, is an independent prognostic factor. This result led us to speculate that PD-L1 expression on TILs, rather than tumour cells, could be more relevant to the inhibitory effects. The predictive role of PD-L1 expression on TILs was also observed in urothelial carcinoma. Some reports have found a positive association between PD-L1 expression on TILs and response to PD-1 inhibitor treatment 7. A phase I clinical trial evaluating the efficacy to MPDL3280A, an anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody, found a correlation between PD-L1 expression on TILs and treatment response in several solid tumour types 22. These results support the use of PD-L1 expression on TILs as a predictive biomarker in GC for inmmunotherapies.

Previous studies have reported a relationship between PD-L1 expression and clinicopathological parameters in various cancer types 25-27. PD-L1 overexpression on tumour cells of GC patients has reportedly been associated with various clinicopathological variables, such as pathological stage, tumour size, and location 16, 26, 27. In our study, we found no significant relationship between PD-L1 expression on tumour cells and clinicopathological variables, including age, gender, stage, surgery, or tumour location in GC patients, except for type of differentiation. Patients with poor differentiation had a higher rate of positive PD-L1 expression on tumour cells. With regard to TILs, several studies have reported that PD-L1 expression is not associated with clinicopathological features 28. In our study, we observed a correlation between PD-L1 expression on TILs and pathological stage and surgery. PD-L1 overexpression was significantly higher in patients without surgery or those in stage III/IV. Several reasons may contribute to the differences between the present and previous findings. First, the baseline characteristics among these studies are of great heterogeneity and their outcomes could be affected. Second, inter-laboratory detection for PD-L1 expression is unstable, so this may affect the relationship between PD-L1 expression and clinicopathological variables. Third, the standard of high and low PD-L1 expression differed among these studies.

Our study had some limitations. First, it was a retrospective analysis, which may be affected by potential selection biases. Second, more research is needed to explore the intrinsic mechanisms by which PD-L1 expression on TILs affects survival in GC patients. Finally, the heterogeneity of PD-L1 expression on the tumour environment may limit the ability to adequately assess the data presented herein.

Conclusion

PD-L1 was expressed not only on tumour cells but also on TILs. PD-L1 expression on tumour cells was associated with differentiation, and its expression on TILs was correlated with both stage and surgery. Additionally, PD-L1 expression on TILs, but not tumour cells, was significantly associated with OS, and was identified as an independent prognostic factor. Our findings suggest that PD-L1 expression on TILs may be a predictive factor for immunotherapy using PD-1/PD-L1 pathway inhibitors.

Table 5.

Univariable and Multivariable Cox Regression Analyses Predicting OS in 240 Patients with gastric cancer

| Parameters | Median OS | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | P | HR(95%CI) | P value | ||

| Ages,years | |||||

| ≤59 | 16.7 (14.0-19.5) | referent | - | ||

| >59 | 14.0 (11.3-16.6) | 1.058 (0.819-1.365) | 0.667 | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 15.6 (13.3-17.9) | referent | - | ||

| Male | 15.1(12.7-17.5) | 1.094 (0.828-1.444) | 0.527 | ||

| Stage | |||||

| Ⅰ-Ⅱ | 23.9 (17.6-30.2) | referent | - | referent | - |

| Ⅲ-Ⅳ | 14.2 (12.7-15.8) | 1.556 (1.119-2.165) | 0.009 | 1.339(0.955-1.878) | 0.080 |

| Differentiation | |||||

| Poor | 14.4 (12.7-16.1) | referent | - | ||

| Well | 17.7 (11.8-23.6) | 0.795(0.601-1.052) | 0.109 | ||

| Tumor PD-L1 | |||||

| Negative | 19.52(15.49-23.55) | referent | - | - | |

| Positive | 19.31(16.93-21.68) | 0.991(0.740-1.328) | 0.954 | ||

| TIL PD-L1 | |||||

| Negative | 18.3(14.0-22.5) | referent | - | referent | - |

| Positive | 14.2(11.8-16.6) | 1.622(1.229-2.140) | 0.001 | 1.502(1.130-1.995) | 0.005 |

| Surgery | |||||

| No | 10.0(5.4-14.5) | referent | - | referent | - |

| Yes | 16.1 (14.0-18.1) | 0.481(0.341-0.678) | <0.001 | 0.516(0.365-0.730) | <0.001 |

| Tumor location | |||||

| Proximal | 15.6 (11.8-19.4) | ||||

| Remote | 15.4 (12.7-18.2) | ||||

| Body | 14.9 (12.9-16.9) | referent | |||

| other | 15.3 (4.5-26.2) | 1.079(0.947-1.230) | 0.253 | ||

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; HR, hazard ratio;TIL:tumor infiltration lymphocyte

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Tingting Cai for her excellent technical assistance.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM. et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee J, Lim DH, Kim S. et al. Phase III trial comparing capecitabine plus cisplatin versus capecitabine plus cisplatin with concurrent capecitabine radiotherapy in completely resected gastric cancer with D2 lymph node dissection: the ARTIST trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:268–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yazici O, Sendur MA, Ozdemir N. et al. Targeted therapies in gastric cancer and future perspectives. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:471–89. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i2.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rizvi NA, Mazieres J, Planchard D. et al. Activity and safety of nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, for patients with advanced, refractory squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 063): a phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:257–65. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70054-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR. et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ. et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2455–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Guillebon E, Roussille P, Frouin E. et al. Anti program death-1/anti program death-ligand 1 in digestive cancers. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2015;7:95–101. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v7.i8.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alsina M, Moehler M, Hierro C. et al. Immunotherapy for Gastric Cancer: A Focus on Immune Checkpoints. Target Oncol. 2016;11:469–77. doi: 10.1007/s11523-016-0421-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hino R, Kabashima K, Kato Y. et al. Tumor cell expression of programmed cell death-1 ligand 1 is a prognostic factor for malignant melanoma. Cancer-Am Cancer Soc. 2010;116:1757–66. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishii H, Azuma K, Kawahara A. et al. Significance of programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression and its association with survival in patients with small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:426–30. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellmunt J, Mullane SA, Werner L. et al. Association of PD-L1 expression on tumor-infiltrating mononuclear cells and overall survival in patients with urothelial carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:812–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tamura T, Ohira M, Tanaka H. et al. Programmed Death-1 Ligand-1 (PDL1) Expression Is Associated with the Prognosis of Patients with Stage II/III Gastric Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:5369–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y, Huang S, Gong D. et al. Programmed death-1 upregulation is correlated with dysfunction of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T lymphocytes in human non-small cell lung cancer. Cell Mol Immunol. 2010;7:389–95. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2010.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hino R, Kabashima K, Kato Y. et al. Tumor cell expression of programmed cell death-1 ligand 1 is a prognostic factor for malignant melanoma. Cancer-Am Cancer Soc. 2010;116:1757–66. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schalper KA, Velcheti V, Carvajal D. et al. In situ tumor PD-L1 mRNA expression is associated with increased TILs and better outcome in breast carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:2773–82. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang L, Qiu M, Jin Y. et al. Programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression on gastric cancer and its relationship with clinicopathologic factors. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:11084–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eto S, Yoshikawa K, Nishi M. et al. Programmed cell death protein 1 expression is an independent prognostic factor in gastric cancer after curative resection. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:466–71. doi: 10.1007/s10120-015-0519-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hou J, Yu Z, Xiang R. et al. Correlation between infiltration of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells and expression of B7-H1 in the tumor tissues of gastric cancer. Exp Mol Pathol. 2014;96:284–91. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu C, Zhu Y, Jiang J. et al. Immunohistochemical localization of programmed death-1 ligand-1 (PD-L1) in gastric carcinoma and its clinical significance. Acta Histochem. 2006;108:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu YX, Wang XS, Wang YF. et al. Prognostic significance of PD-L1 expression in patients with gastric cancer in East Asia: a meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:2649–54. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S102616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim JW, Nam KH, Ahn SH. et al. Prognostic implications of immunosuppressive protein expression in tumors as well as immune cell infiltration within the tumor microenvironment in gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:42–52. doi: 10.1007/s10120-014-0440-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herbst RS, Soria JC, Kowanetz M. et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature. 2014;515:563–7. doi: 10.1038/nature14011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geng L, Huang D, Liu J. et al. B7-H1 up-regulated expression in human pancreatic carcinoma tissue associates with tumor progression. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134:1021–7. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0364-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan ZK, Ye F, Wu X. et al. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of programmed cell death ligand1 (PD-L1) expression in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:462–70. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.02.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fang W, Hong S, Chen N. et al. PD-L1 is remarkably over-expressed in EBV-associated pulmonary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma and related to poor disease-free survival. Oncotarget. 2015;6:33019–32. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boger C, Behrens HM, Mathiak M. et al. PD-L1 is an independent prognostic predictor in gastric cancer of Western patients. Oncotarget. 2016;7:24269–83. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamura T, Ohira M, Tanaka H. et al. Programmed Death-1 Ligand-1 (PDL1) Expression Is Associated with the Prognosis of Patients with Stage II/III Gastric Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:5369–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zou MX, Peng AB, Lv GH. et al. Expression of programmed death-1 ligand (PD-L1) in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes is associated with favorable spinal chordoma prognosis. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8:3274–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]