Abstract

Objectives

Financial strain represents a perceived inability to meet financial needs and obligations and is associated with poorer health outcomes. Distinct facets of perceived social support may mitigate the deleterious effects of financial strain on health. The present study examined the extent to which appraisal, belonging, and tangible social support ameliorate the effects of financial strain on health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

Methods

A community sample (N = 238; 67.2% female; MAge = 43.4 years, SD = 13.1) completed in-person surveys as part of a larger study of health behaviors.

Results

Greater financial strain and less social support were associated with poorer HRQoL. Additionally, both appraisal and belonging support moderated the effects of financial strain on some HRQoL components, such that higher appraisal and belonging support were associated with diminished effects of financial strain on HRQoL.

Conclusions

These findings suggest nuanced associations between financial strain and HRQoL. Implications for prevention and intervention programs are discussed.

Keywords: financial strain, social support, health-related quality of life, buffering effect

INTRODUCTION

Financial strain refers to difficulty affording food, clothing, housing, major items (eg, car), furniture/household equipment, leisure activities, and bills1 and represents an undesirable mismatch between income and the combination of expenses and accumulated debt.2 In this way, financial strain does not represent objective measures of socioeconomic status (SES), but rather income inadequacy relative to expenses. Importantly, financial strain is related to, but distinct from, income and other traditional SES indicators.3–5 As evidence of its distinction, there is considerable variation in the severity of financial strain experienced by people of a similar income strata.6 Additionally, unlike traditional, objective measures of SES, financial strain is applicable to individuals of all SES strata. Heightened financial strain can negatively impact self-esteem and personal control.7,8 Theoretical models of stress posit that the chronic stress that develops as a byproduct of financial strain can lead to poorer health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease, elevated blood pressure, overall poor physical health, and depression.1,6,9,10

Despite the strong association between financial strain and health outcomes, little work has examined how financial strain may impact health more broadly. Specifically, extant work has focused on presence of disease, whereas health is comprehensively defined as a ‘state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being—not merely the absence or presence of disease or infirmity’.11 Thus, it is important to not only examine objective measures of health, but also consider health-related quality of life (HRQoL). HRQoL is a multidimensional assessment of well-being and health status that captures both physical and mental health, and thus can help determine how disease, injury, and disability impact physical and mental health problems that are not disease or disorder-specific.12 Indeed, poorer HRQoL is associated with higher mortality rates and a higher prevalence of disability.13,14 This construct can also aid in identifying subgroups with relatively poor perceived health across multiple domains and may inform interventions that target these subgroups.12 Despite the clear utility and importance of examining HRQoL determinants, little work has been devoted to this effort.

Robust evidence indicates that lower SES, as measured by either objective or subjective measures, is associated with poorer HRQoL.15,16 Interestingly, subjective measures of SES (eg, subjective social status) have been shown to predict HRQoL even after controlling for objective measures of SES,15 suggesting that subjective measures may capture elements of SES that uniquely relate to poor HRQoL. Conceptually, financial strain may contribute to poorer HRQoL after accounting for traditional, objective SES items because this construct taps into an element of subjective SES that is not assessed by traditional SES items (eg, inadequate income to expenses ratio).17 Indeed, initial empirical evidence suggests that greater financial strain contributes to poor self-rated health (1 element of HRQoL) after controlling for objective SES.18,19 Thus, despite overlap between subjective and objective financial strain,20 the uniqueness of subjective financial strain appears to affect HRQoL to a greater extent. However, this line of research has been limited to only one aspect of HRQoL. Given that improving HRQoL and identifying its determinants is a central public health goal,12 it is imperative that work focus on elucidating determinants of poor HRQoL across its multiple dimensions. Moreover, identifying modifiable determinants of HRQoL may provide clinicians with avenues to address potential health disparities.

In addition to evaluating determinants of HRQoL, there may be utility in identifying buffers that mitigate the adverse effects of financial strain on HRQoL. Most notably, perceived social support is posited to buffer the effects of stressful events on health.21–23 For instance, social support by partners of unemployed job seekers is associated with lower relationship discord and depressive symptoms in both partners.24 Moreover, in line with theoretical models of chronic stress, empirical data indicates that the negative impact of financial strain on mental health outcomes, including depressive symptoms,25 and poorer self-rated health,26 is offset by greater social support. In addition to a potential buffering effect of social support, greater social support is also empirically associated with decreased stress and improved health behavior27 as well as inversely related to poor HRQoL.28 This evidence suggests personal and social factors may work in tandem to modulate the relationship between financial strain and HRQoL.

Despite promising initial evidence supporting the premise that social support may counteract the impact of financial strain on health, no research has examined the stress buffering effects of perceived social support on the association between financial strain and HRQoL. Notably, previous work maintains that specific dimensions of social support may be more or less effective as coping resources in the presence of financial strain, yet little effort has been devoted to elucidating these potentially differential effects. As some research has found social capital, encompassing both community resources as well as family and friend connections, mitigates the adverse impacts of financial strain on self-rated health,6 the extent to which tangible versus emotional resources more or less buffer these relationships remains unknown. Such findings have the ability to more directly inform clinical efforts toward fostering specific forms of social support for individuals experiencing financial strain. Thus, the current work has the potential for high practical utility and theoretical significance.

The current study addressed these gaps by examining the relation between financial strain, perceived social support, and 4 indicators of poor HRQoL (ie, self-rated health, poor mental and physical health days, and activity limited days due to poor physical or mental health) among a diverse community sample of adults. Consistent with extant theoretical and empirical work that posits related, yet unique dimensions of social support,29 the current study examined 3 dimensions of perceived social support (ie, appraisal, belonging, and tangible support) separately. It was hypothesized that greater financial strain and lower perceived social support, across each dimension of perceived social support, would relate to poorer HRQoL outcomes. Additionally, consistent with the stress-buffering hypothesis,21 it was hypothesized that the effect of financial strain on HRQoL would depend on level of perceived social support. Specifically, we hypothesized that financial strain would be more strongly related to HRQoL among those with low, as opposed to high, levels of perceived social support.

METHODS

Participants

A total of 248 adults were recruited from the Dallas metropolitan area through flyers posted for a health behavior study on the University of Texas Southwestern campus and local advertising circulars.30 A convenience sampling approach was used. Individuals were eligible to participate in the study if they were at least 18 years of age, possessed a valid home address, a functioning telephone number, and demonstrated > 6th grade English literacy level on the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM).31,32 Of those screened, 10 were excluded because they were not able to demonstrate the minimum literacy level, leaving a total study sample of 238 participants.

Measures

Socioeconomic status/demographic variables

Sex, race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White vs. Non-White), age (years), years of education (0 = No formal schooling to 20 = Post-graduate degree), health insurance status (0 = no health insurance, 1= any health insurance), and past year family income (0 = Less than $5000 to 8 = $100,000 or greater) were assessed. Consistent with previous work,15 years of education and past year family income were treated as continuous variables.

Financial strain questionnaire

The financial strain questionnaire (adapted from an economic strain measure)1 is an 8-item questionnaire used to assess participants' difficulty with affording food, clothing, housing, major items, furniture, leisure activities, and bills. Items were rated on a scale from 0 to 4 (eg, no difficulty, some difficulty, great difficulty, and could not afford). Total scores could range from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating greater financial strain (α = .91).

Interpersonal support evaluation list

The Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL-12)29 is a 12-item self-report measure of the perceived availability of social support, which contains 3 subscales. The appraisal (advice or guidance) subscale measures the perceived availability of others with whom one can talk about problems. The belonging (empathy, acceptance, concern) subscale measures the perceived availability of others’ with whom one may engage in activities. Finally, the tangible support subscale measures the perceived availability of material aid (help or assistance, such as material or financial aid). Items are rated on a 4-point scale, and scores range from 4 to 16 on each subscale. For the present study, the appraisal (α = .80), belonging (α = .84), and tangible support (α = .82) subscales were utilized, with higher scores indicating greater social support.

Health-related quality of life

Items to assess health related quality of life (HRQoL) were drawn from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey.33 Items assessed (a) self-rated health; (b) poor physical health days; (c) poor mental health days; and (d) activity limited days due to poor physical or mental health. Self-rated health was assessed with a single item with which participants rated their health on a 5-point scale from poor (1) to excellent (5). Consistent with prior work,18,34 self-rated health was dichotomized (0 = poor, fair; 1 = good, very good, excellent). This item has been shown to prospectively predict mortality across studies.14 The number of poor physical health days during the past month was assessed with the question: “Now thinking about your physical health, which includes physical illness and injury, for how many days during the past 30 days was your physical health not good?” The number of poor mental health days during the past month was assessed by: “Now thinking about your mental health, which includes stress, depression, and problems with emotions, for how many days during the past 30 days was your mental health not good?” Lastly, participants reported the number of days in the previous 30 days in which poor physical or mental health limited their ability to perform usual activities. These items have demonstrated excellent to moderate retest reliability.35

Procedure

Data were collected as part of a quasi-experimental intervention study that examined the short-term impact of a mobile phone intervention on sedentary time in a diverse community sample.30 Interested individuals contacted the research office and were briefly pre-screened for basic eligibility criteria, including at least 18 years of age, possessing a valid home address, and having a functioning telephone number (see Participants section above); those eligible at the pre-screener were scheduled to attend the initial study visit. The details of the study were reviewed at the first visit, eligibility was verified via the REALM, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Eligible participants completed study questionnaires on laptop computers and some participated in the intervention. Briefly, the intervention study was a post hoc addition to a study designed to characterize proximal predictors of health behavior using mobile phone–based ecological momentary assessment. See Kendzor and colleagues30 for additional details of the study design. Participants received a $50 gift card and a parking token for the completion of the initial visit. The current study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, and the University of Houston. The current study is based on secondary analyses of the initial visit (pre-intervention) data. Data collection began in December 2012 and concluded in November 2013.

Analytic Strategy

Sample descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations among study variables were examined. Next, the main and interactive effects of financial strain and perceived social support on HRQoL were tested. Self-rated health was examined with a logistic regression (Model 1). The 3 other dimensions of HRQoL (i.e., poor physical health days, poor mental health days, and activity limited days due to poor physical or mental health) were examined using generalized estimating equations (GEE) wherein they were treated as a multivariate outcome (Model 2). GEEs were employed because of the interest in the marginal expectations.36 More specifically, we were interested in the average estimated number of poor HRQoL days across all 3 days items for a set of predictors. A benefit to this analytic approach is that it reduces the potential for spurious findings by limiting the number of separate analyses needed to study HRQoL items with commensurate responding. Thus, 2 outcomes were of interest in the present study: (1) dichotomous self-rated health and (2) multivariate outcome created from the 3 days HRQoL items. The 3 poor health days HRQoL items (ie, poor physical health days, poor mental health days, and activity limited days due to poor physical or mental health) exhibited a negative binominal distribution; thus a negative binominal distribution was specified with a log link for the GEEs and an unstructured correlation structure was specified for each GEE. Coefficients were exponentiated to derive Rate Ratios (RR), which can be interpreted as percent increases or decreases in outcomes for each unit increase in the predictor. Three separate logistic and 3 separate GEE models were conducted to examine each dimension of social support (appraisal, belonging, and tangible support) as independent moderators of the associations between financial strain and HRQoL. The predictor and moderators were centered to improve interpretability. The predictor, moderator, interaction term, and covariates, including sex, race, age, education, health insurance status, and past year family income, were simultaneously entered into the model. For GEE models, the rate of change, percent increases or decreases in outcomes for each unit increase in the predictor, was examined at 1 SD above and below the centered moderator for each analysis. A Bonferroni correction was employed to decrease rate of Type 1 error. Based on this correction, level of significance was adjusted to .017 (ie, .05/3) for the logistic regression parameters as well as the GEE parameters.

RESULTS

Descriptive Analyses

The majority of participants were African American (51.7%) and female (67.2%) with an average age of 43.4 (SD = 13.1) years. See Table 1 for participant characteristics. Zero-order correlations among all study variables are presented in Table 2. Overall, financial strain was negatively correlated with the 3 social support subscales and correlated with all 4 HRQoL items (ie, negative correlation with self-rated health and positive correlations with number of poor mental and physical health days and activity limited days). Social support subscales positively correlated with one another, and were significantly correlated with HRQoL items (ie, positive correlation with self-rated health and negative correlations with number of poor mental and physical health days and activity limited days). All HRQoL items were correlated with one another. Specifically, weak negative correlations emerged between self-rated health and all other HRQoL items (rs range: −0.26 to −0.34), and moderate positive correlations emerged between poor physical health days, poor mental health days, and limited activity due to poor health days (rs range: 0.44 to 0.57).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| M(SD)/N[%] | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Men | 78 [32.8] | -- |

| Women | 160 [67.2] | -- |

| Race | ||

| African American | 123 [51.7] | -- |

| Non-Hispanic White | 73 [30.7] | -- |

| Hispanic | 28 [11.8] | -- |

| Asian | 8 [3.4] | -- |

| American Indian | 2 [0.8] | -- |

| Multiracial | 4 [1.7] | -- |

| Age | 43.4 (13.1) | 19–68 |

| Education (years completed) | 13.7 (2.4) | 5–20 |

| Health Insurance | ||

| No Health Insurance | 93 [39.1] | -- |

| Any Health Insurance | 145 [60.9] | -- |

| Family Income for Past 12 Months | ||

| Less than $5000 | 58 [24.4] | -- |

| $5000–11, 999 | 31 [13.0] | -- |

| $12,000–15,999 | 16 [6.7] | -- |

| $16,000–24,999 | 21 [8.8] | -- |

| $25,000–34,999 | 18 [7.6] | -- |

| $35,000–49,999 | 29 [12.2] | -- |

| $50,000–74,999 | 27 [11.3] | -- |

| $75,000–99,999 | 18 [7.6] | -- |

| $100,000 or greater | 18 [7.6] | -- |

| Financial Strain Score | 10.9 (7.7) | 0–24 |

| Perceived Social Support | ||

| Appraisal Subscale | 13.2 (3.1) | 4–16 |

| Belonging Subscale | 12.6 (3.1) | 4–16 |

| Tangible Support Subscale | 13.0 (3.0) | 4–16 |

| Health-related Quality of Life | ||

| Self-Rated Health (% poor/fair) | 66 [27.7] | -- |

| Poor Physical Health Days | 2.8 (5.9) | 0–30 |

| Poor Mental Health Days | 4.5 (7.0) | 0–30 |

| Limited Activity Due to Poor Health Days | 2.1 (5.0) | 0–30 |

Note. N = 238; M(SD) = Mean (Standard Deviation). Education: 0 = no formal schooling to 20 = post-graduate degree); Financial strain: Financial Strain Questionnaire;1 Perceived social support: Interpersonal Evaluation List subscales;29 Heath-related quality of life: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System items.33

Table 2.

Correlations among Variables

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Sex | -- | |||||||||||||

| 2. | Race | .06 | -- | ||||||||||||

| 3. | Age | -.01 | .10 | -- | |||||||||||

| 4. | Education | .07 | −.36*** | −.28*** | -- | ||||||||||

| 5. | Health Insurance | −.14* | .27*** | .13* | −.25*** | -- | |||||||||

| 6. | Income | .11 | −.26*** | −.17** | .54*** | −.45*** | -- | ||||||||

| 7. | Financial Strain | .05 | .21** | .25*** | −.46*** | .40*** | −.68*** | -- | |||||||

| 8. | Appraisal Subscale | .15* | −.08 | −.18** | .30*** | −.10 | .26*** | −.40*** | -- | ||||||

| 9. | Belonging Subscale | .10 | .08 | −.20** | .10 | .01 | .09 | −.32*** | .63*** | -- | |||||

| 10. | Tangible Support Subscale | .14* | .03 | −.17** | .22** | −.09 | .27*** | −.42*** | .72*** | .76*** | -- | ||||

| 11. | Self-Rated Healtha | −.05 | −.19** | −.22*** | .20** | −.06 | .12 | −.30*** | .35*** | .28*** | .25*** | -- | |||

| 12. | Poor Physical Health Days | −.02 | −.08 | .21** | −.16* | .02 | −.16* | .23*** | −.13* | −.15* | −.23*** | −.34*** | -- | ||

| 13. | Poor Mental Health Days | .02 | −.05 | .03 | −.09 | .04 | −.11 | .20** | −.26*** | −.25*** | −.30*** | −.31*** | .44*** | -- | |

| 14. | Limited Activity Due to Poor Health Days | .07 | −.03 | .11 | −.20** | −.05 | −.11 | .29*** | −.23*** | −.22** | −.29*** | −.26*** | .45*** | .57*** | -- |

N = 238;

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05.

Note. Point-biseral and biseral correlations were conducted for correlations that included a dichotomous variable and continuous variable whereas Pearson’s correlations were conducted for correlations that included 2 continuous variables. All non-dichotomous variables were treated as continuous (see59). Sex: 0=men and 1=women; Race: 0=Non-Hispanic White and 1=Non-White; Education: 0 = no formal schooling to 20 = post-graduate degree; Insurance Status: 0= Any health insurance and 1=No health insurance; Annual family income: 0 = less than $5,000 to 8 = $100,000 or greater; Financial strain: Financial Strain Questionnaire;1 Appraisal, belonging, and tangible support subscales: Interpersonal Evaluation List subscales;29 Self-rated health (0=poor/fair and 1=good/very good/excellent), poor physical health days, poor mental health days, and limited activity due to poor health days: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System items.33 Financial strain, appraisal subscale, belonging subscale, and tangible support subscale are scored such that larger values represent more optimum outcomes; poor physical health days, poor mental health days, and limited activity due to poor health days are scored such that smaller values represent more optimum outcomes.

Correlations between the continuous self-rated health item and other health-related quality of life items (ie, poor physical health, poor mental health, and limited activity days) evinced consistently lower correlations relative to observed correlations among poor physical health, poor mental health, and limited activity days (r’s range: −0.29 to −0.39).

Financial Strain and Self-rated Health

Three logistic regression models were conducted with self-rated health as the outcome and financial strain, social support (each dimension entered separately in its respective model), the interaction term, and covariates as predictors. The first model included the appraisal subscale and was significant (χ2 (9) = 54.20, p < .001, Pseudo R2 = .19). The conditional main effects, ie, effect of predictor when interacting predictor is zero, of financial strain and appraisal support were significant. Specifically, greater financial strain was associated with greater odds of reporting poor/fair self-rated health, and less perceived appraisal support was associated with greater odds of reporting poor/fair self-rated health. The interaction term, ie, financial strain by appraisal support, was non-significant; see Table 3.

Table 3.

Odds ratio results from logistic regression analyses for main and interactive effects of financial strain and dimensions of perceived social support on self-rated health.

|

Appraisal Subscale as Moderator

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | |||||

| OR | SE | p | Lower | Upper | |

|

|

|||||

| Sex | 0.617 | 0.229 | .193 | 0.298 | 1.276 |

| Race | 0.384 | 0.162 | .023 | 0.168 | 0.878 |

| Age | 0.972 | 0.014 | .049 | 0.946 | 1.000 |

| Education | 1.054 | 0.095 | .563 | 0.883 | 1.258 |

| Insurance Status | 1.152 | 0.438 | .710 | 0.547 | 2.428 |

| Income | 0.822 | 0.080 | .043 | 0.679 | 0.994 |

| Financial Strain | 0.908 | 0.030 | .003 | 0.852 | 0.968 |

| Appraisal Subscale | 1.236 | 0.077 | .001 | 1.094 | 1.397 |

| Financial Strain * Appraisal | 0.996 | 0.007 | .603 | 0.982 | 1.011 |

|

| |||||

|

Belonging Subscale as Moderator

| |||||

| 95% CI | |||||

| OR | SE | p | Lower | Upper | |

|

|

|||||

| Sex | 0.675 | 0.246 | .282 | 0.330 | 1.381 |

| Race | 0.343 | 0.145 | .011 | 0.150 | 0.784 |

| Age | 0.975 | 0.014 | .068 | 0.949 | 1.002 |

| Education | 1.101 | 0.098 | .277 | 0.925 | 1.310 |

| Insurance Status | 1.132 | 0.425 | .740 | 0.543 | 2.363 |

| Income | 0.835 | 0.080 | .061 | 0.691 | 1.008 |

| Financial Strain | 0.906 | 0.029 | .003 | 0.850 | 0.966 |

| Belonging Subscale | 1.185 | 0.074 | .007 | 1.049 | 1.339 |

| Financial Strain * Belonging | 0.993 | 0.008 | .402 | 0.978 | 1.009 |

|

| |||||

|

Tangible Support Subscale as Moderator

| |||||

| 95% CI | |||||

| OR | SE | p | Lower | Upper | |

|

|

|||||

| Sex | 0.670 | 0.245 | .274 | 0.327 | 1.373 |

| Race | 0.348 | 0.147 | .012 | 0.153 | 0.795 |

| Age | 0.970 | 0.013 | .031 | 0.944 | 0.997 |

| Education | 1.068 | 0.094 | .451 | 0.900 | 1.268 |

| Insurance Status | 1.196 | 0.442 | .628 | 0.580 | 2.468 |

| Income | 0.820 | 0.078 | .037 | 0.680 | 0.988 |

| Financial Strain | 0.903 | 0.029 | .002 | 0.848 | 0.962 |

| Tangible Subscale | 1.111 | 0.075 | .120 | 0.973 | 1.267 |

| Financial Strain * Tangible | 1.005 | 0.008 | .561 | 0.989 | 1.021 |

Note. N=238. Sex: 0=men and 1=women; Race: 0=Non-Hispanic White and 1=Non-White; Education: 0 = no formal schooling to 20 = post-graduate degree; Insurance Status: 0= Any health insurance and 1=No health insurance; Annual family income: 0 = less than $5,000 to 8 = $100,000 or greater; Financial strain: Financial Strain Questionnaire;1 Appraisal, belonging, and tangible support subscales: Interpersonal Evaluation List subscales;29 Self-Rated Health (0 = poor/fair and 1 = good/very good/excellent): Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System items.33

The second model included the belonging subscale and was significant (χ2(9) = 48.66, p < .001, Pseudo R2 = .17). The conditional main effects of financial strain and belonging support were significant. Specifically, greater financial strain was associated with greater odds of reporting poor/fair self-rated health, and less perceived belonging support was associated with greater odds of reporting poor/fair self-rated health. The interaction term, ie, financial strain by belonging support, was non-significant; see Table 3.

The third model included the tangible subscale and was significant (χ2(9) = 45.88, p < .001, Pseudo R2 = .16). The conditional main effect of financial strain was significant, and the conditional main effect of tangible support was non-significant. Specifically, greater financial strain was associated with greater odds of reporting poor/fair self-rated health. The interaction term, ie, financial strain by belonging support, was not significant; see Table 3.

Financial Strain and Multivariate Days Outcome

Model with appraisal support as moderator

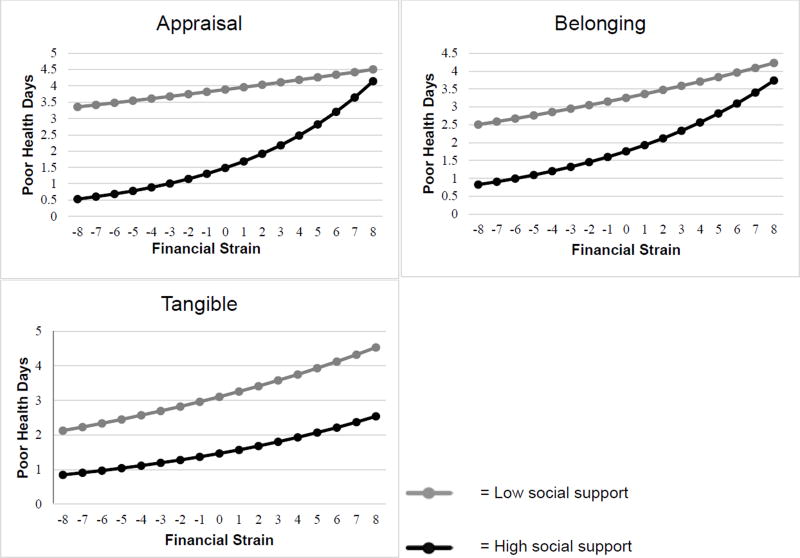

Table 4 displays the results of the GEE analyses that examined the remaining HRQoL dimensions (ie, poor physical health days, poor mental health days, and activity limited days due to poor physical or mental health) as a combined outcome in a multivariate framework and financial strain, social support (each dimension entered separately in its respective model), the interaction term, and covariates as predictors. Conditional main effects revealed that greater financial strain and less perceived appraisal support were associated with a greater number of HRQoL days in the past month. The interaction term between financial stain and the appraisal subscale was significant. Examination of rates of change revealed a significant rate of change between financial strain and poor HRQoL days among participants with high perceived appraisal support (RR = 1.14, p < .001). Interpretation of the Rate Ratio suggested that for each unit increase in financial strain, participants with high perceived appraisal support experienced 14% more poor HRQoL days. Financial strain was not significantly associated with rate of change in poor HRQoL days among participants with low perceived appraisal support (RR = 1.02, p = .17). See Figure 1.

Table 4.

Results from GEE analyses for main and interactive effects of financial strain and dimensions of perceived social support on health-related quality of life outcomes.

| Appraisal Subscale as Moderator

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | |||||

| b | SE(b) | p | Lower | Upper | |

|

|

|||||

| Sex | .420 | .130 | .001 | .165 | .674 |

| Race | −.624 | .138 | <.001 | −.894 | −.354 |

| Age | .008 | .005 | .087 | −.001 | −.018 |

| Education | −.034 | .031 | .280 | −.095 | .027 |

| Insurance Status | −.413 | .139 | .003 | −.686 | −.141 |

| Income | .013 | .033 | .698 | −.051 | .077 |

| Financial Strain | .073 | .010 | <.001 | .051 | .096 |

| Appraisal Subscale | −.156 | .021 | <.001 | −.199 | −.113 |

| Financial Strain * Appraisal | .018 | .003 | <.001 | .013 | .023 |

|

| |||||

|

Belonging Subscale as Moderator

| |||||

| 95% CI | |||||

| b | SE(b) | p | Lower | Upper | |

|

|

|||||

| Sex | .249 | .134 | .063 | −.014 | .512 |

| Race | −.355 | .145 | .015 | −.639 | −.070 |

| Age | .007 | .005 | .139 | −.002 | −.017 |

| Education | −.078 | .032 | .015 | −.141 | −.015 |

| Insurance Status | −.292 | .145 | .044 | −.577 | .008 |

| Income | .011 | .035 | .751 | −.057 | .079 |

| Financial Strain | .064 | .012 | <.001 | .040 | .087 |

| Belonging Subscale | −.100 | .023 | <.001 | −.145 | −.055 |

| Financial Strain * Belonging | .008 | .003 | .006 | .002 | .014 |

|

| |||||

|

Tangible Support Subscale as Moderator

| |||||

| 95% CI | |||||

| b | SE(b) | p | Lower | Upper | |

|

|

|||||

| Sex | .261 | .135 | .053 | −.003 | .527 |

| Race | −.384 | .145 | .008 | −.669 | −.100 |

| Age | .008 | .005 | .107 | −.002 | −.018 |

| Education | −.080 | .032 | .013 | −.144 | .017 |

| Insurance Status | −.245 | .145 | .092 | −.530 | .040 |

| Income | .054 | .034 | .115 | −.013 | .122 |

| Financial Strain | .058 | .012 | <.001 | .035 | .082 |

| Tangible Subscale | −.126 | .024 | <.001 | −.173 | −.078 |

| Financial Strain * Tangible | .004 | .003 | .210 | −.002 | .009 |

Note. N=238. Sex: 0=men and 1=women; Race: 0=Non-Hispanic White and 1=Non-White; Education: 0 = no formal schooling to 20 = post-graduate degree; Insurance Status: 0= Any health insurance and 1=No health insurance; Annual family income: 0 = less than $5,000 to 8 = $100,000 or greater; Financial strain: Financial Strain Questionnaire;1 Appraisal, belonging, and tangible support subscales: Interpersonal Evaluation List subscales;29 Poor physical health days, poor mental health days, and limited activity due to poor health days: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System items.33

Figure 1.

Predicted number of poor health days across high and low levels of social support dimensions across levels of financial strain. Financial strain was centered at the mean. Social support was recentered at 1 standard deviation above and below the mean to derive high and low values, respectively.

Model with belonging support as moderator

Conditional main effects revealed that greater financial strain and less perceived belonging support were associated with a greater number of poor HRQoL days in the past month. The interaction term between financial strain and the belonging subscale was significant. Examination of rates of change revealed a significant rate of change between financial strain and poor HRQoL days across participants with low and high perceived belonging support (RR = 1.04, p = .011 and RR = 1.09, p < .001, respectively). Interpretation of the rate ratio suggests that for each unit increase in financial strain, participants low on belonging support reported 4% more poor HRQoL days. Among participants high on belonging support, a 1 unit increase in financial strain was associated with 9% more poor HRQoL days. See Figure 1.

Model with tangible support as moderator

Conditional main effects revealed that greater financial strain and less perceived tangible support were also associated with more poor HRQoL days in the past month. The interaction term between financial stain and perceived tangible support was non-significant (p > .05). See Figure 1.

DISCUSSION

Current findings provide preliminary evidence for the deleterious effect of financial strain on health-related quality of life, the benefit of social support on heath-related quality of life, and the buffering agency of social support dimensions for the negative impact of financial strain on health-related quality of life among a diverse community sample of adults. Importantly, the current study extends existing literature by examining associations between financial strain, social support, and health-related quality of life assessed across all 4 CDC HRQoL items. Specifically, self-rated health was evaluated individually, and poor physical and mental health days and days with limited activity resulting from poor physical or mental health were examined as a single multivariate outcome of health-related quality of life (ie, poor health days outcome). Consistent with hypotheses, greater financial strain was associated with poorer health-related quality of life across both outcomes. In partial support of hypotheses, less appraisal and belonging social support were related to both poorer health-related quality of life outcomes, but tangible support was only associated with the days outcome. Finally, results indicated a significant moderating role of the appraisal subscale and belonging subscale for the relation between financial strain and health-related quality of life outcome that concurrently assessed poor physical and mental health days as well as days with limited activity resulting from poor physical or mental health (ie, poor health days outcome). Importantly, these relations were significant after controlling for theoretically-relevant covariates, including sex, race, age, education, health insurance status, and income.

Findings indicated that financial strain and facets of social support were significantly associated with health-related quality of life within the current sample. Consistent with previous work, financial strain and appraisal and belonging dimensions of social support were related to self-rated health.26,37 Interestingly, the tangible support subscale was not related to self-rated health. Extant work among college students also indicated a non-significant association between tangible support and self-rated health.37 This may reflect offsetting effects of receiving tangible support, which may provide practical assistance but may also be associated with shame and stigma.38,39 Thus, perceiving that one has emotional support and a perception of belonging to a community may be more salient predictors of self-rated health than perceiving one is able to receive material support if needed, which may be associated with negative self-conscious emotions. Additionally, current results indicated that financial strain and social support not only negatively impact self-rated health, but also the poor health days outcome. Although the current study focused on subjective health across multiple domains, current findings largely align with empirical work on objective measures of health. Given the extensive evidence indicating an association between objective and subjective measures of health,40,41 current findings may, in part, stem from a central conceptual factor that subjective and objective measures of health share. Nevertheless, these findings bolster support for influential theoretical models of stress, social support, and health and extend this work by highlighting the salience of subjective health across multiple domains. Together, the current work underscores the importance of financial strain and social support as social determinants of poor health among adults.

Although it was hypothesized that all 3 dimensions of social support would buffer against the negative impact of financial strain on health-related quality of life, inconsistent moderating effects were observed. Specific to self-rated health, none of the social support dimensions had a significant impact on the negative association between financial strain and this outcome. Thus, whereas financial strain and 2 dimensions of social support (ie, appraisal and belonging) uniquely related to self-rated health, there was no interaction between these determinants. Extensive work has implicated a robust association between financial stressors and poorer self-rated health.14,19,42 As such, the benefit of general social support may not be strong enough to combat this association. Importantly, however, other research suggests that perceived social support related to specific groups (eg, church-based social support) may be more pertinent to the relation between financial strain and self-rated health than perceived social support more generally (ie, not organization specific).26 Because the current measure of social support was intended to assess general social support across each of the 3 dimensions and did not specify a specific group/organization it is possible that different findings may have emerged had we assessed social support across specific areas of life. Future research may consider examining how group/organization-specific (eg, church, work place, family) social support may moderate the impact of financial strain on self-rated health.

In partial support of hypotheses, the appraisal and belonging support dimensions moderated the relation between financial strain and the poor health days outcome. High appraisal and belonging social support had the strongest buffering effect when lower financial strain was reported. Thus, findings highlight that perceived availability of others and belonging support may be most impactful when lower levels of financial strain are experienced. Additionally, tangible support did not emerge as a significant moderator. Previous work has reported mixed findings regarding tangible support as a buffer against poor health outcomes.25,43 Consistent with Krause and colleagues,25 tangible support may not be as relevant of a social support dimension to protect against deleterious effect of financial strain on health as the other dimensions. Specifically, in contrast to other stressors related to poorer health outcomes, the effects of financial strain may be more fundamentally related to psychosocial factors rather than tangible factors, as supported by the present findings. Additionally, for some individuals, financial strain is chronic.44 The perception that others are available to offer material or financial support may be perceived as a short-term solution to a chronic problem, and may not get to the crux of how financial strain negatively impacts health. Continued research is needed to further delineate and corroborate the present findings.

Theoretically, the present findings add to the rich and ever expanding literature on social capital theory45 by bridging the typically disparate areas of research focused on economic and social inequality and social networks. The present study, unique from extant work, highlights how one’s perception of their financial adequacy can impact health and the effect of social capital or support has on these relations. Moreover, the current data are largely incongruent with the neo-materialistic perspective, which suggests that inadequate access to resources accounts for the relation between social determinants of health, such as financial strain, and poor health.46–48 Indeed, that tangible social support did not emerge as a buffer against the negative influence of financial strain on poorer health-related quality of life, and appraisal and belonging support demonstrated moderating effects for the aforementioned relation, to a degree, provides evidence for the appropriateness of taking a psychosocial approach to understanding these associations. For example, psychosocial factors more closely related to affect, such as perceived guidance and acceptance from others, may be more likely to offset deleterious effects of financial strain on health-related quality of life rather than perceived financial support; thus, it does not appear that the mere inadequacy of money leads to poorer health.

Clinically, current findings underscore the impact of financial strain on poor health-related quality of life among a diverse community sample, and highlight the importance of emotional and belonging social support. Based on these data, it may be advisable for community prevention and intervention programs targeted toward individuals at risk of or living with moderate to lower levels of financial strain to integrate money management education and skills training with psychoeducation on the potential positive benefits of social support for coping. This might include programs reaching the newly divorced, education associated with bankruptcy filings, credit counseling, and other debtor or debt consolidation counseling/programming. Considering the recent economic crisis, it may be beneficial for such programs to develop and disseminate educational materials and skills training opportunities that discuss the detrimental impact of financial strain and the associated stress on physical and mental health, as well as provide a platform where those experiencing financial strain have the opportunity to practice behaviors that may lead to decreased financial strain, including budgeting, identifying and discussing needs from wants, and tracking money spent. The nature of these programs and groups may in and of themselves provide an opportunity to develop social support, particularly appraisal and belonging support, from others experiencing similar difficulties. Indeed, for in-person groups addressing the aforementioned aspects of financial strain, such discussions may have the added benefit of facilitating a sense of connectedness and support among group members, which may ultimately act as a protective factor against poor health-related quality of life.

Although not a primary aim of the investigation, there are several noteworthy findings from the current data. First, it is noteworthy that the social support dimensions were related, but distinct constructs. Indeed, these constructs shared approximately 40–58% of the variance. Similarly, the variance shared between each social support dimension and financial strain varied (appraisal: 16%; belonging: 10%; tangible: 18%). This observation provides additional empirical evidence for the distinctiveness of the social support dimensions as well as the uniqueness of financial strain from social support constructs. In light of the current findings for the unique buffering effects and the limited shared variance with one another and disparate overlap with financial strain, the current study provides additional empirical evidence that these 3 dimensions of social support are distinct and should be considered individually in empirical work. Second, present findings provided additional support for the uniqueness of financial strain and income. Specifically, these constructs shared 46% of their variance; suggesting that these dimensions of SES are related, yet distinct constructs. As further evidence for their unique properties, tests of multicollinearity were explored. Guidelines to identify multicollinearity suggest a tolerance value of less than .10 or .20 and a variance inflation factor (VIF) value of greater than 10 may indicate multicollinearity (see49 for review). Across all models, the tolerance and VIF statistics did not indicate multicollinearity (financial strain: tolerance range [.44-.46], VIF range [2.17–2.28]; income: tolerance range [.43-.44], VIF range [2.26–2.31]). Thus, the present data provide further evidence for the uniqueness of financial strain and income, and also underscore the importance of considering both dimensions of SES when examining their impact on health outcomes.

There are several limitations to the current study. First, the present work was cross-sectional and therefore causality cannot be determined. Future work is needed to prospectively determine directional effects of the observed associations. Indeed, a longitudinal design would provide clearer, more robust information about these relations. Second, the current study relied on self-report measures and outcomes derived from single item measures. Future research could benefit by utilizing multi-method approaches and minimizing the role of method variance in the observed relations as well as employing a structural equation modeling approach to examine relations. Although a more parsimonious multivariate model was employed to 3 of the 4 health-related quality of life items in the present study, a structural equation model may be a useful tool to comprehensively model HRQoL across all 4 items. Indeed, this is an important area for future research given resent work that has identified a unidimensional latent HRQoL construct across the 4 items (see50). Additionally, the currently employed HRQoL measure captures very specific, and albeit somewhat limited, dimensions of HRQoL. Despite the numerous advantages of the presently employed measure,51 alternative measures of HRQoL, such as the Short Form Survey Instrument52 or the WHO Quality of Life Assessment,53 may offer more comprehensive evaluations of this construct and should be explored in future studies. Along similar lines, future research would benefit from examining the proposed relations using objective measures of social support, as the current study included only measures of perceived social support.

Third, the current study focused on social support as a moderator and did not examine potential mediation pathways that may further explain relations between variables. Thus, despite the current study being guided by influential theoretical work, current findings cannot refute the possibility that the studied variables may operate through an indirect pathway that leads to poorer health-related quality of life, potentially through perceived stress.54 To comprehensively evaluate the potential mediating pathways that may explain the observed relations, future work should be devoted to examining a conceptual moderated-mediation model that considers the effect of financial strain and social support in addition to potential mediators, such as perceived stress, on health-related quality of life outcomes. Fourth, the current sample size did not permit inclusion of additional variables that may have influenced findings. Therefore, it will be important for future research to examine the present pattern of findings in a larger sample wherein additional potential confounds, including substance use,55 exercise,56 and chronic illness,57 can be controlled. Similarly, considering the secondary data analysis nature of the present study, an a priori power analysis was not conducted. To ensure adequate power to detect effects for more complex models, an a priori power analysis should be conducted prior to data collection.

Finally, participants in the present study represented a convenience sample of adults from a single metropolitan area (Dallas, TX) who were willing to participate in a paid research study. As a result, relative to reports from the Census Bureau for the ethnic breakdown and median income of this area,58 the present study over-sampled African Americans and adults from lower income strata, and under-sampled non-Hispanic Whites and Hispanic. Thus, although the sample benefitted from racial/ethnic diversity, the generalizability of results may be limited, in part, due to selection bias. Indeed, participants who enrolled in the present study may have been more motivated to participate for compensation relative to general community members and/or may have had a specific interest in sedentary behavior intervention studies. As such, the present findings should be interpreted as preliminary evidence for the observed relations; yet, potential biases resulting from the present sample may preclude generalizability beyond the present sample. In an effort to extend current findings to a broader population, additional research is needed to evaluate the observed pattern of findings in a community sample more representative of the population from which it is derived as well as using data derived from a population-based survey study.

The present study contributes to the wider literature by providing preliminary evidence for social support as a protective element against the deleterious effects of stress on health outcomes, specifically, health-related quality of life among a community sample of adults. Moreover, the current research extends previous literature by highlighting the importance of considering social support as a multi-faceted construct with differential predictive abilities with regard to health outcomes and as a buffering agent for stress. Perceptions that one’s peers, family, or friends provide social support through emotional or physical connections may be more influential on health than perceptions that one can receive material or financial support, even when experiencing stress related to financial difficulties. Prevention and intervention programs aimed at reducing the negative effects of financial strain may benefit from strengthening healthy social bonds that encourage perceptions of availability and belonging support.

Acknowledgments

American Cancer Society (US) (MRSGT-10-104-01-CPHPS) (PI: Darla E Kendzor, PhD)

American Cancer Society (US) (MRSGT-12-114-01-CPPB) (PI: Michael S Businelle, PhD)

National Institutes of Health (US) (P30CA016672)

National Institute of Drug Abuse (F31DA043390) (PI: Lorra Garey, MA)

Footnotes

Human Subjects Approval Statement

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, and the University of Houston. Informed consent was obtained from screened eligible participants prior to data collection.

Conflict of Interest and Disclosure Statement

All authors of this article declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Lorra Garey, Department of Psychology, University of Houston, Houston, TX.

Lorraine R. Reitzel, Department of Psychological, Health, and Learning Sciences, University of Houston, Houston, TX.

Amber M. Anthenien, Department of Psychology, University of Houston, Houston, TX.

Michael S. Businelle, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK.

Clayton Neighbors, Department of Psychology, University of Houston, Houston, TX.

Michael J. Zvolensky, Department of Psychology, University of Houston, Houston, TX.

David W. Wetter, University of Utah and the Huntsman Cancer Institute, Salt Lake City, UT.

Darla E. Kendzor, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK.

References

- 1.Pearlin LI, Lieberman MA, Menaghan EG, Mullan JT. The stress process. J Health Soc Behav. 1981;22(4):337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peirce RS, Frone MR, Russell M, Cooper ML. Relationship of financial strain and psychosocial resources to alcohol use and abuse: The mediating role of negative affect and drinking motives. J Health Soc Behav. 1994;35(4):291–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kahn JR, Pearlin LI. Financial Strain over the Life Course and Health among Older Adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2006;47(1):17–31. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmerman FJ, Katon W. Socioeconomic status, depression disparities, and financial strain: what lies behind the income-depression relationship? Health economics. 2005;14(12):1197–1215. doi: 10.1002/hec.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szanton SL, Allen JK, Thorpe RJ, et al. Effect of financial strain on mortality in community-dwelling older women. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2008;63(6):S369–S374. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.6.s369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frank C, Davis CG, Elgar FJ. Financial strain, social capital, and perceived health during economic recession: A longitudinal survey in rural Canada. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2014;27(4):422–438. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2013.864389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayhew KP, Lempers JD. The relation among financial strain, parenting, parent self-esteem, and adolescent self-esteem. J Early Adolesc. 1998;18(2):145–172. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Price RH, Choi JN, Vinokur AD. Links in the chain of adversity following job loss: How financial strain and loss of personal control lead to depression, impaired functioning, and poor health. J Occup Health Psychol. 2002;7(4):302–312. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.7.4.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steptoe A, Brydon L, Kunz-Ebrecht S. Changes in financial strain over three years, ambulatory blood pressure, and cortisol responses to awakening. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(2):281–287. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000156932.96261.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams ED, Kooner I, Steptoe A, Kooner JS. Psychosocial factors related to cardiovascular disease risk in UK South Asian men: A preliminary study. Br J Health Psychol. 2007;12(4):559–570. doi: 10.1348/135910706X144441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Official Records of the World Health Organization. Vol. 2. Geneva, Switzerland: 1946. Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization as adopted by the International Health Conference; p. 100. In: (ed.) OW, ed. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor VR. Measuring healthy days: Population assessment of health-related quality of life. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Adult and Community Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jia H, Muennig P, Lubetkin E, Gold M. Predicting geographical variations in behavioural risk factors: An analysis of physical and mental healthy days. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(2):150–155. doi: 10.1136/jech.58.2.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;28(1):21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garey L, Reitzel LR, Kendzor DE, Businelle MS. The potential explanatory role of perceived stress in associations between subjective social status and health-related quality of life among homeless smokers. Behav Modif. 2016;40(1–2):303–324. doi: 10.1177/0145445515612396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zahran HS, Kobau R, Moriarty DG, et al. Health-related quality of life surveillance— United States, 1993–2002. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2005;54(4):1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Angel RJ, Frisco M, Angel JL, Chiriboga DA. Financial strain and health among elderly Mexican-origin individuals. J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44(4):536–551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Castro A, Gee GC, Takeuchi DT. Examining alternative measures of social disadvantage among Asian Americans: The relevance of economic opportunity, subjective social status, and financial strain for health. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12(5):659–671. doi: 10.1007/s10903-009-9258-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Savoy EJ, Reitzel LR, Nguyen N, et al. Financial strain and self-rated health among Black adults. Am J Health Behav. 2014;38(3):340–350. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.38.3.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adler NE, Epel ES, Castellazzo G, Ickovics JR. Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy, White women. Health Psychol. 2000;19(6):586–592. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.6.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98(2):310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lakey B, Cohen S. Social support theory and measurement. Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists. 2000:29–52. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thoits PA. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. J Health Soc Behav. 2011;52(2):145–161. doi: 10.1177/0022146510395592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vinokur AD, Price RH, Caplan RD. Hard times and hurtful partners: How financial strain affects depression and relationship satisfaction of unemployed persons and their spouses. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;71(1):166–179. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krause N. Chronic financial strain, social support, and depressive symptoms among older adults. Psychol Aging. 1987;2(2):185–192. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.2.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krause N. Exploring the stress-buffering effects of church-based and secular social support on self-rated health in late life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61(1):S35–S43. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.1.s35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bandiera FC, Atem F, Ma P, Businelle MS, Kendzor DE. Post-quit stress mediates the relation between social support and smoking cessation among socioeconomically disadvantaged adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;163:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strine TW, Chapman DP, Balluz L, Mokdad AH. Health-related quality of life and health behaviors by social and emotional support: Their relevance to psychiatry and medicine. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43(2):151–159. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0277-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, Hoberman HM. Social Support: Theory, Research and Applications. Springer; 1985. Measuring the functional components of social support; pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kendzor DE, Shuval K, Gabriel KP, et al. Impact of a mobile phone intervention to reduce sedentary behavior in a community sample of adults: A quasi-experimental evaluation. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(1) doi: 10.2196/jmir.5137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: A shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993;25(6):391–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy PW, Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, Decker BC. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine (REALM): A quick reading test for patients. J Reading. 1993;37(2):124–130. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prevention CDC. [Accessed December 12 2014];Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey. 2013 http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/pdf-ques/2013brfss_english.pdf.

- 34.Chang H-L, Fisher FD, Reitzel LR, Kendzor DE, Nguyen MAH, Businelle MS. Subjective sleep inadequacy and self-rated health among homeless adults. Am J Health Behav. 2015;39(1):14–21. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.39.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andresen EM, Catlin TK, Wyrwich KW, Jackson-Thompson J. Retest reliability of surveillance questions on health related quality of life. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(5):339–343. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.5.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghisletta P, Spini D. An introduction to generalized estimating equations and an application to assess selectivity effects in a longitudinal study on very old individuals. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2004;29(4):421–437. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hale CJ, Hannum JW, Espelage DL. Social support and physical health: The importance of belonging. J Am Coll Health. 2005;53(6):276–284. doi: 10.3200/JACH.53.6.276-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bolger N, Zuckerman A, Kessler RC. Invisible support and adjustment to stress. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79(6):953–961. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.6.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keene DE, Cowan SK, Baker AC. ‘When You’re in a Crisis Like That, You Don’t Want People to Know’: Mortgage strain, stigma, and mental health. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(5):1008–1012. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hagstromer M, Ainsworth BE, Oja P, Sjostrom M. Comparison of a subjective and an objective measure of physical activity in a population sample. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7(4):541–550. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.4.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pinquart M. Correlates of subjective health in older adults: A meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. 2001;16(3):414. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.16.3.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tucker-Seeley RD, Harley AE, Stoddard AM, Sorensen GG. Financial hardship and self-rated health among low-income housing residents. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(4):442–448. doi: 10.1177/1090198112463021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Åslund C, Larm P, Starrin B, Nilsson KW. The buffering effect of tangible social support on financial stress: Influence on psychological well-being and psychosomatic symptoms in a large sample of the adult general population. Int J Equity Health. 2014;13(1):85. doi: 10.1186/s12939-014-0085-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kahn JR, Pearlin LI. Financial strain over the life course and health among older adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2006;47(1):17–31. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Szreter S, Woolcock M. Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33(4):650–667. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krieger N, Chen JT, Coull BA, Selby JV. Lifetime socioeconomic position and twins’ health: An analysis of 308 pairs of United States women twins. PLoS Med. 2005;2(7):e162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Link BG, Phelan JC. Understanding sociodemographic differences in health--the role of fundamental social causes. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(4):471–473. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.4.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Phelan JC, Link BG, Diez-Roux A, Kawachi I, Levin B. “Fundamental Causes” of social inequalities in mortality: A test of the theory. J Health Soc Behav. 2004;45(3):265–285. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O’brien RM. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual Quant. 2007;41(5):673–690. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yin S, Njai R, Barker L, Siegel PZ, Liao Y. Summarizing health-related quality of life (HRQOL): Development and testing of a one-factor model. Popul Health Met. 2016;14(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s12963-016-0091-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Slabaugh SL, Shah M, Zack M, et al. Leveraging health-related quality of life in population health management: The case for healthy days. Popul Health Manag. 2016;20(1):13–22. doi: 10.1089/pop.2015.0162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saxena S, Carlson D, Billington R, Orley J. The WHO quality of life assessment instrument (WHOQOL-Bref): The importance of its items for cross-cultural research. Qual Life Res. 2001;10(8):711–721. doi: 10.1023/a:1013867826835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adams DR, Meyers SA, Beidas RS. The relationship between financial strain, perceived stress, psychological symptoms, and academic and social integration in undergraduate students. J Am Coll Health. 2016;64(5):362–370. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2016.1154559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Coste J, Quinquis L, D’Almeida S, Audureau E. Smoking and health-related quality of life in the general population. Independent relationships and large differences according to patterns and quantity of smoking and to gender. PloS one. 2014;9(3):e91562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Focht BC. Exercise and health-related quality of life. In: Acevedo EO, editor. The Oxford Handbook of Exercise Psychology. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Megari K. Quality of life in chronic disease patients. Health Psychol Res. 2013;1(3) doi: 10.4081/hpr.2013.e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.United States Census Bureau. [Accessed April 20, 2017];QuickFacts 2015: Dallas, TX (on-line) Available at: https://http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/LND110210/4819000.

- 59.Rhemtulla M, Brosseau-Liard PÉ, Savalei V. When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychol Methods. 2012;17(3):354–373. doi: 10.1037/a0029315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]