Abstract

Background

Lysosomal dysfunction is implicated in human heart failure for which ischemic heart disease is the leading cause. Altered myocardial expression of cathepsin D (CTSD), a major lysosomal protease, was observed in human heart failure but its pathophysiological significance has not been determined.

Methods and Results

Western blot analyses revealed an increase in the precursor but not the mature form of CTSD in myocardial samples from explanted human failing hearts with ischemic heart disease, which is recapitulated in chronic myocardial infarction produced via coronary artery ligation in Ctsd+/+ but not Ctsd+/− mice. Mice deficient of Ctsd displayed impaired myocardial autophagosome removal, reduced autophagic flux, and restrictive cardiomyopathy. After induction of myocardial infarction, weekly serial echocardiography detected earlier occurrence of left ventricle chamber dilatation, greater decreases in ejection fraction and fractional shortening, and lesser wall thickening throughout the first 4 weeks; pressure-volume relationship analyses at 4-week revealed greater decreases in systolic and diastolic functions, stroke work, stroke volume, and cardiac output; greater increases in the ventricular weight to body weight and the lung weight to body weight ratios and larger scar size were also detected in Ctsd+/− mice compared with Ctsd+/+ mice. Significant increases of myocardial autophagic flux detected at 1 and 4 weeks after induction of myocardial infarction in the Ctsd+/+ mice were diminished in the Ctsd+/− mice.

Conclusions

Myocardial CTSD upregulation induced by myocardial infarction protects against cardiac remodeling and malfunction, which is at least in part through promoting myocardial autophagic flux.

Keywords: autophagy, myocardial infarction, protease, cathepsin D, gene targeting

Subject codes: Basic Science Research, Heart Failure, Myocardial Infarction, Chronic Ischemic Heart Disease, Myocardial Biology

Intracellular protein degradation takes place primarily in proteasomes and lysosomes. Proteasomal and lysosomal dysfunctions are associated with cardiac pathogenesis but the pathophysiological significance of these changes remains poorly understood.1 Substrates are delivered to, and degraded by, lysosomes through either heterophagy or autophagy. Autophagy is further classified into microautophagy, chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA), and macroautophagy;1 of which only macroautophagy requires formation of autophagosomes to send cargos to lysosomes. Although microautophagy and CMA in cardiomyocytes are rarely studied, macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy) has been extensively investigated for its involvement in cardiac health and disease.2, 3 However, it is worthy note that among the many reports on alterations of cardiac autophagy, only a few have emphasized that inadequate lysosomal degradation could be a potential underlying cause for the observed increases in autophagosomes.4–9 This is because the concept “autophagic flux” was not widely recognized then and, as a result, it often was not vigorously assessed.10

Cargo digestion within lysosomes relies on lysosomal hydrolases. The most important lysosomal hydrolases are protease cathepsins.11 Cathepsins are subdivided into 3 subfamilies based on the active-site amino acids: the serine proteases cathepsin A (CTSA) and CTSG, the aspartic proteases CTSD and CTSE, and the cysteine cathepsins (i.e., cathepsins B, C, F, H, K, L, O, S, V, X, and W).12 Several cathepsins were investigated for their cardiac roles using genetically modified animal models. For example, Ctsl deficiency was shown to hasten cardiac remodeling and dysfunction after myocardial infarction (MI) and exacerbate cardiac pathology induced by aortic constriction in mice;13, 14 whereas knockout of Ctsb or Ctsk displayed protection against pressure overload-induced maladaptive cardiac remodeling.15, 16 Ctsk deficiency also attenuated aging-induced cardiac dysfunction and high fat diet-induced cardiac hypertrophy and malfunction in mice.17, 18 These studies indicate that the role of different cathepsins in cardiac pathogenesis varies and must be determined individually.

Cathepsin D (CTSD) is ubiquitously and abundant ly expressed cathepsin, synthesized in the rough endoplasmic reticulum as preprocathepsin D which contains a signal peptide targets the 52kD procathepsin D (CTSD-p) to the endosomal-lysosomal pathway.19, 20 Removal of the 44 amino acid N-terminal propeptide produces the 48kD intermediate form and a further proteolytic cleavage results in the CTSD mature form (CTSD-m) consisting of a 34kD and a 14kD chain.20 With the creation of Ctsd global knockout mice,21 CTSD has been studied for its role in immune homeostasis22, apoptosis,23 cancer development,24, 25 neurodegeneration,26, 27 and retina diseases.28 Changes in myocardial CTSD expression are also frequently used as an indicator of autophagic activity, assuming a key role for CTSD in lysosomal degradation of autophagosomes;29–31 however, this assumption has not been formally tested.

A potentially significant involvement of CTSD derangement in cardiovascular pathophysiology has been suggested by clinical observations. For examples, decreased myocardial CTSD protein levels in human dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and increased plasma levels of CTSD in patients with acute coronary syndrome were reported;32, 33 furthermore, a higher level of serum CTSD was associated with atherogenesis,34 increased risk of coronary events,35 carotid intima-media thickness,36 and endothelial dysfunction.37 However, important questions regarding how CTSD deficiency affects cardiac function and whether the altered myocardial CTSD expression plays an important role in cardiac pathogenesis remain unanswered. Hence, we sought to address them in this study.

Here we demonstrate that myocardial CTSD-p but not CTSD-m proteins are increased in human end-stage heart failure (HF) resulting from ischemic heart disease (IHD) and in mouse model of chronic MI, CTSD is required for autophagosome removal and thereby promotes autophagic flux in mouse hearts, myocardial CTSD upregulation induced by MI protects against post-MI cardiac remodeling and malfunction and this protection is at least in part through increasing myocardial autophagic flux.

Methods

Human Myocardial CTSD Detection

Left ventricular (LV) free wall tissues were collected from explanted human hearts with end-stage HF resulting from ischemic heart disease (IHD) during cardiac transplantation using a standardized protocol. Informed consent was obtained at the time each subject was listed for transplant. Four non-failing controls without a history of cardiac diseases were procured from brain-dead organ donors whose hearts were deemed unacceptable for transplantation. Informed consent for research use of these hearts was obtained from the appropriate next kin by the organ procurement organization (Gift of Life, Inc., Philadelphia, PA). All hearts were arrested in situ with ice-cold cardioplegia solution (Viaspan®, DuPont, Wilmington, DE), transported to the laboratory on wet ice, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen within two hours, and stored at −80°C until protein extraction was performed. The research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Minnesota. All research was conducted in compliance with Good Clinical Practice standards and all applicable NIH research requirements. For western blot analyses, crude proteins were extracted using the RIPA buffer.38

Animal Models

Creation of mice with germline ablation of Ctsd was reported.21 The Ctsd+/− mice were maintained in the C57BL/6 inbred background. Permanent ligation of the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) was performed to induce MI in 3-month-old mixed-sex Ctsd+/+ and Ctsd+/− mice under anesthesia and mechanical ventilation.

The protocol for the care and use of animals in this study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of South Dakota and conforms to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996).

Western Blot Analyses

Western blot analyses for specific proteins in myocardium were performed as previously described.39

Immunofluorescence Confocal Microscopy

Cryosections of 4% paraformaldehyde fixed ventricular myocardium were processed for immunofluorescence staining of CTSD and confocal microscopy as we previously described.40

Autophagic Flux Assay

Mice were intraperitoneally injected with bafilomycin-A1 (BFA1, LC Laboratories; 1.868mg/kg) or vehicle control (DMSO). At 1 hour after the injection, ventricular myocardium was sampled from the mice for western blot analyses for LC3-II levels as previously described.4

Echocardiography

Two-dimensional echocardiogram guided M-mode echocardiography was performed on anesthetized mice as previously described.41

Pressure-Volume Relationship Analyses

Mice anesthetized via inhalation of 2.5% Isoflurane were orally intubated and mechanically ventilated. A 1.4F Millar Mikro-Tip catheter transducer (model SPR-839, Millar Instruments) was inserted into the right common carotid artery and advanced to the LV chamber. After stabilizing for 30min, LV pressure and volume were recorded; the other parameters were derived from the PowerLab software.40 Both saline calibration and cuvette calibration were applied before data exportation.

Infarct Scar Size Determination

Perfusion fixed LV was processed to obtain 5-μm cryosections. Masson trichrome staining (Thermo Scientific kit) was conducted on LV cross-sections at the papillary muscle level, and digital images were captured with a microscope. The fibrotic area (i.e., the infarct scar size) stained blue was measured using ImagePro Plus 6.0 software. The percentage of scar size was calculated as reported.42

Statistics

Western blot densitometry data are presented as dot plots with mean±SEM superimposed, where differences between 2 groups or among multiple groups were evaluated in SPSS for statistical significance using respectively un-equal variance t test or Welch’s ANOVA followed by Games-Howell test. Statistical tests for other results are specified table footnotes or figure legends. P value <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Alterations of myocardial CTSD proteins in HF resulting from IHD

Myocardial expression of cathepsins has not been well studied in IHD. Hence, we measured myocardial CTSB, CTSD, and CTSK protein levels in explanted human hearts with IHD. Western blot analyses revealed a significant increase in CTSD precursor (CTSD-p) but not the mature form (CTSD-m) in human HF resulting from IHD, compared with the non-failing donor hearts (Figure 1A~1C). However, no significant changes in CTSB or CTSK were discerned in the same human samples (Supplementary Figure I). We also measured myocardial CTSB, CTSD, and CTSK proteins in a mouse model of surgically induced MI. The results show that myocardial Ctsd-p and Ctsd-m were significantly increased at 7 and 14 days post-MI and, in agreement with the findings from human IHD, CTSD-p remained increased but the CTSD-m returned to a level only modestly higher than the sham control level by 28 days post-MI when more severe HF was evident (Figure 1D~1F). CTSB proteins were also markedly increased while mature CTSK was slightly decreased (p<0.01) at 7 days post-MI; however, both returned to the sham control level by 28 days post-MI (Supplementary Figures II, III).

Figure 1. Changes in myocardial CTSD protein levels in heart failure resulting from IHD.

A–C: Representative images and densitometry data of western blot analyses for myocardial CTSD in explanted human hearts with IHD. D–F: Representative images and densitometry data of western blot analyses for myocardial CTSD in wild type mice at the indicated time points after myocardial infarction (MI). Both CTSD precursor (CTSD-p) and the 34-kD mature (CTSD-m) forms were detected and quantified. N=3 males +1 female for each group. G: Fluorescence confocal micrographs. Cryosections of myocardial samples from 7-day post MI or sham control were processed for immunofluorescence staining for CTSD (red). F-actin was stained with Alexa Fluor® 488 Phalloidin (green) and the nuclei stained blue with DAPI. The added white dash line in the border zone row demarcates between infarct zone and the survival area. **p<0.01.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analyses showed that myocardial Ctsd mRNA levels in the infarct zone and in the remote area at 7 days post-MI were ~6.5 and 4 folds of those in the sham controls (Supplementary Figure IV). Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy reveals that the increases of CTSD proteins are evident in both the infarct zone and the remote area where CTSD is primarily located in cardiomyocytes (Figure 1G). Taken together, the data from both humans and animal experiments consistently show an upregulation of cardiac CTSD-p in HF resulting from IHD, prompting us to determine the pathophysiological significance of CTSD derangement.

Ctsd is required for autophagosome removal in mouse hearts

Although Ctsd null mice were characterized for non-cardiac defects, the role of Ctsd in autophagy remains obscure. To test whether Ctsd participates in autophagosome removal, we performed myocardial LC3-II flux assay in Ctsd+/−, Ctsd+/− and Ctsd+/+ littermate mice at baseline. Ctsd+/− mice displayed ~50% reduction of all forms of CTSD proteins in the heart compared with Ctsd+/+ mice and, as expected, neither CTSD-p nor CTSD-m were detectable in Ctsd−/− mice (Figure 2A~2C). Importantly, myocardial LC3-II in Ctsd−/− mice was significantly increased (Figure 2D, 2E and data not shown). To decipher the cause of the LC3-II increase, we treated the mice with bafilomycin A1 (BFA1), an inhibitor of the vacuolar proton ATPase that is known to inhibit lysosomal function and the fusion between autophagosomes and lysosomes.43 We found that myocardial LC3-II were significantly increased at 1 hour after BFA1 administration in both WT and Ctsd+/− mice, but this increase was very modest in Ctsd−/− mouse (Figure 2D, 2E); meanwhile, there was no significant difference in myocardial LC3-II levels among the three genotypes treated with BFA1. These data indicate that myocardial autophagic flux is severely decreased by Ctsd deficiency and Ctsd indeed plays an essential role in removing autophagosomes in the heart.

Figure 2. Myocardial autophagic flux is decreased in Ctsd null mice.

A–C: Western blot analyses for myocardial CTSD in 24-day-old wild type (WT), Ctsd+/− and Ctsd−/− mice. D and E: Myocardial autophagic flux assays in mice. Bafilomycin A1 (BFA1, 3μmol/kg body weight) or vehicle control (DMSO) was administrated via an intraperitoneal injection 1 hour before tissue harvest. N=2 males + 2 females for each group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

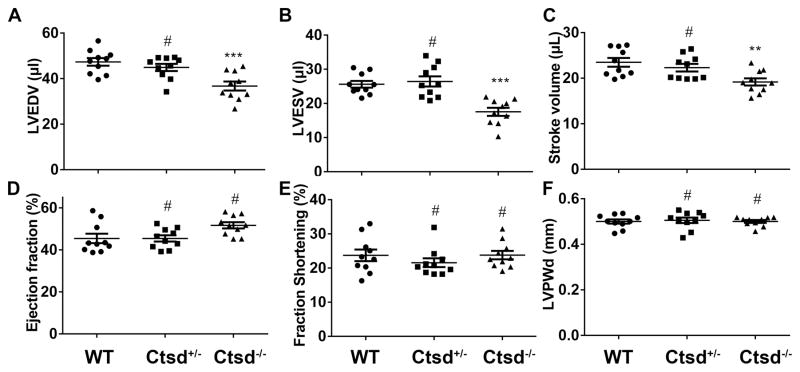

Ctsd−/− mice develop restrictive cardiomyopathy

The neural, endocrinal, digestive, and immunological phenotypes of Ctsd deficient mice were widely studiedsystems;20, 21, 44 however, the impact of Ctsd deficiency on the cardiovascular system surprisingly has not been reported. Despite 50% reduction of myocardial CTSD proteins (Figure 2), Ctsd+/− breeder mice at baseline did not display any discernible gross abnormality at least for their first 10 months of age but Ctsd−/− mouse lifespan is less than 4 weeks (Supplementary Figure V), in agreement with previous reports.21 Echocardiography studies revealed significant decreases in LV end-diastolic and end-systolic dimensions and volumes (p<0.001) and in stroke volume (p<0.01) in Ctsd−/− mice, compared with the Ctsd+/+ littermate mice at 24 days of age; however, the ejection fraction (EF), fractional shortening (FS), and posterior wall thickness were not discernibly altered Echocardiography did not reveal any abnormality in the Ctsd+/− mice (Figure 3, Supplementary Figure VI). These data indicate that Ctsd deficiency causes restrictive cardiomyopathy.

Figure 3. Parameters derived from echocardiography.

M-mode echocardiography was performed on 24-day-old mice of the indicated genotypes. Values are expressed as means ± SEM from 10 mice per group. WT, wild type littermate (4 males + 6 females); for Ctsd+/−, n=5 males+5 females; for Ctsd−/−, n= 6 males + 4 females; LVEDV, left ventricular end diastolic volume; LVESV, left ventricular end systolic volume; #p>0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, vs. the WT group, one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey’s test.

Dynamic changes in post-MI myocardial autophagic flux

Autophagy in post-MI hearts was studied in a few previous reports but autophagic flux has not been vigorously examined.30, 31, 45 Hence, we determined myocardial autophagic flux in wild type mice at 7, 14, and 28 days post-MI. The border zone of the infarct induced by LAD ligation and the equivalent area of sham control were harvested at 1 hour after intraperitoneal injection of lysosome inhibitor BFA1 or vehicle control. The BFA1 treatment significantly increased LC3-II in both sham and MI groups, indicative of the effective lysosomal inhibition by BFA1 and detectable clearance of autophagosomes in myocardium within the 1 hour duration. Among vehicle-treated groups, although none of the post-MI groups showed significantly higher LC3-II than their sham controls, there is a tendency that LC3-II decreases from 7 to 28 days post-MI, with the difference between 7-day and 28-day post-MI being statistically significant. Among BFA1-treated groups, LC3-II levels in all the MI groups were significantly higher than that in the sham controls but there were no significant differences among the post-MI groups (Figure 4). Taken together, these results demonstrate that myocardial autophagic flux is persistently elevated within 28 days post-MI.

Figure 4. Dynamic changes in LV function and chamber dimension and in myocardial autophagic flux.

A and B: LV ejection fraction and end diastolic internal diameter (LVIDd) were derived from serial echocardiography performed on the day before (0 day, 3 months of age) and weekly after the permanent LAD ligation (3 males + 4 females) or sham surgery (2 males + 3 females) in wild type mice. Data were analyzed in SAS Studio using a two way repeated-measures ANOVA. Violations of the sphericity assumption resulted in the use of the Huynh-Feldt correction. Tukey’s HSD test was used for pair-wise comparison for each time point. C and D: Representative images (C) and pooled quantitative data (D) of western blot analyses for myocardial LC3-II to assess autophagic flux. Myocardial samples from the border zone of MI hearts and the equivalent area of sham control hearts were examined. GAPDH on the same membrane was probed for loading control. For each group, 2 male and 2 female mice at 3 months of age were used. *p<0.05 vs. the BFA1 treated sham group; †p<0.05.

Blocking CTSD upregulation exacerbates post-MI cardiac remodeling and malfunction in mice

The role of CTSD upregulation in diseased hearts was unknown; hence, we sought to determine the impact of Ctsd haploinsufficiency on post-MI hearts. As revealed by examinations at 7 and 28 days post-MI, myocardial Ctsd upregulation induced by MI was prevented in the Ctsd+/− mice (Figure 5A~5F) and this blockage is more complete in the remote area than in the infarct zone (Supplementary Figure VII), which was associated with a larger scar size, greater ventricular weight to body weight ratio, and greater lung weight to body weight ratio at 28 days post-MI in the Ctsd+/− MI group compared with the Ctsd+/+ MI group (Figure 5G~5J). Serial echocardiography performed immediately before and 1-, 2-, 3-, and 4-weeks after LAD ligation revealed hastened progression of LV chamber dilatation and malfunction (greater decreases in FS and EF) with diminished LV posterior wall thickening in the Ctsd+/− MI group, compared with the Ctsd+/+ MI group (Figure 6 and Supplementary Figure VIII). The more severe post-MI cardiac malfunction in Ctsd+/− mice than Ctsd+/+ mice at 28 days post-MI was also confirmed by LV P-V relationship analyses (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure IX). Virtually all parameters derived from the P-V relationship are comparable between Ctsd+/− and Ctsd+/+ sham groups. In Ctsd+/+ mice, MI induced significantly decreases in stroke work, stroke volume, cardiac output, EF, FS, maximal dP/dt, and minimal dP/dt and significantly increases in the end diastolic volume, end systolic volume, and Tau. Except for the change in end diastolic volume, all these MI-induced alterations were more pronounced in Ctsd+/− mice. Thus, morphometric and functional assessments overwhelmingly show that blocking Ctsd upregulation exacerbates post-MI cardiac remodeling and malfunction.

Figure 5. Effects of Ctsd haploinsufficiency on post-MI mouse hearts.

A–F: Western blot analyses for myocardial CTSD at 7 days (A–C) and 28 days (D–F) post-MI. For each group, 2 male and 2 female mice at 3 months of age were used. G and H, Scar size at 28 days post-MI determined with Masson’s trichrome staining. Viable myocardium was stained red whereas fibrotic tissue (i.e., infarct area) stained blue. Bar=1mm. Three male and 5 female mice were included for the WT MI group; 5 male+3 female mice for the Ctsd+/− MI group. I, The ventricular weight to body weight ratio (VW/BW) from 5 male and 5 female mice for each group. J, The lung weight to body weight ratio (Lung W/BW) from 4 male and 4 female mice for each group. Unpaired t test (H) or one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey’s test (I, J) was used; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Figure 6. The time course of post-MI cardiac remodeling and malfunction assessed with serial echocardiography.

Ctsd+/− and littermate wild type (WT) mice at 3-months–of-age were subject to LAD ligation (MI) or sham surgery (Sham). Serial echocardiography was performed at one day before (day 0) and 7, 14, 21, and 28 days after the surgery. LV, left ventricle; LVPWd, end-diastolic LV posterior wall thickness; LVPWs, end-systolic LV posterior wall thickness; LVIDd, end-diastolic LV internal dimension; LVIDs, end-systolic LV internal dimension. Mean ± SEM for each time point are plotted. The time course data were converted to area under curve (AUC) for each mouse and the differences in AUC among the 4 groups were evaluated using two way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (see Supplementary Figure XI for detailed AUC comparison). *p<0.05 and **p<0.01, WT MI group (n=7 mice; 3 males+4 females) vs. Ctsd+/− MI group (n=7 mice, 3 males+4 females). n=5 mice (2 males+2 females) for each sham group.

Table 1.

LV Pressure-Volume Relationship Analyses at 28 Days Post-MI

| WT Sham (n=4m+4f) | WT MI (n=3m+5f) | Ctsd+/− Sham (n=4m+4f) | Ctsd+/− MI (n=3m+5f) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 408±2 | 495±11* | 400±2 | 499±6* |

| Stroke work (mmHg*μL) | 717±44 | 435±10* | 717±21 | 229±20*§ |

| Cardiac output (μL/min) | 4323±113 | 3772±169† | 3980±131 | 2729±118*§ |

| Stroke volume (μL) | 9.8±0.7 | 7.1±0.2* | 8.1±0.3 | 5.3±0.3*§ |

| End-systolic volume (μL) | 7.4±0.7 | 16.3±0.6* | 7.6±0.6 | 18.9±0.6*|| |

| End-diastolic volume (μL) | 17.2±0.6 | 23.3±0.6* | 15.6±0.5 | 24.2±0.3* |

| End-systolic pressure (mmHg) | 88.6±1.8 | 90.8±1.5 | 87.8±1.6 | 87.3±1.2 |

| End-diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 8.3±0.7 | 14.4±1.3† | 10.7±0.6 | 21.2±2.0*# |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 69.1±2.6 | 38.3±1.7* | 68.2±3.9 | 23.9±0.9*# |

| dP/dtmax (mmHg/s) | 7118±333 | 5609±139* | 6118±217|| | 4461±176*# |

| −dP/dtmax (mmHg/s) | 5764±229 | 4353±195* | 4964±254 | 3200±84*# |

| Tau (ms) | 10.9±0.4 | 15.0±0.81‡ | 10.7±0.4 | 18.4±1.0*|| |

WT, wild type; m, male; f, female;

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001 vs. the sham group of the same genotype;

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001 vs. WT group undergone the same surgery; two way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test

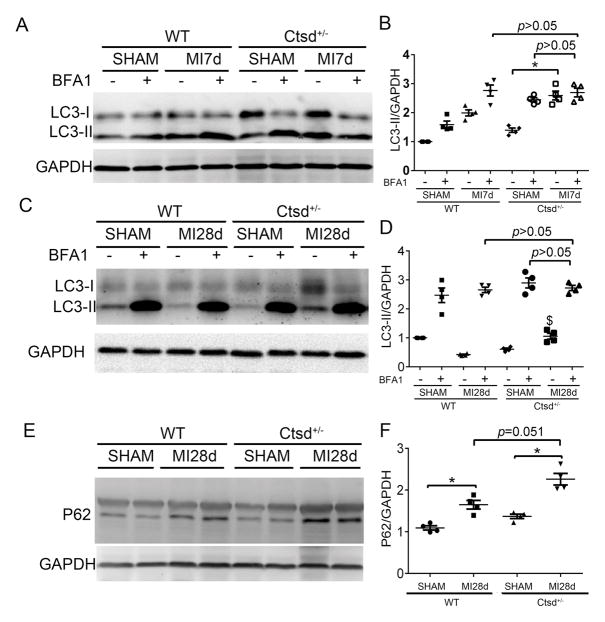

Blocking CTSD upregulation impairs autophagic flux in post-MI hearts

As described earlier, Ctsd deficiency impairs myocardial autophagic flux (Figure 2) and persistent increases of myocardial autophagic flux are evident in post-MI hearts (Figure 4), which prompted us to examine the hypothesis that exacerbation of post-MI cardiac malfunction and maladaptive remodeling by Ctsd haploinsufficiency is caused by impairment of autophagic flux. We compared changes in post-MI myocardial autophagic flux between Ctsd+/− and Ctsd+/+ mice. Consistent with results shown in Figure 4, myocardial LC3-II flux at both 7 and 28 days post-MI was significantly increased in Ctsd+/+ mice; however, this increase was substantially attenuated by Ctsd haploinsufficiency (Figure 7A~7D), indicating that although Ctsd+/− does not affect autophagic flux at baseline it diminishes the MI-induced increase in autophagic flux via impairing autophagosome removal. This conclusion is also supported by changes in p62/SQSTM1 protein levels, a known substrate of autophagy. At 28 days after surgery, myocardial p62 proteins, which were comparable in the sham control groups, were significantly increased by MI and, importantly, this increase tended to be more pronounced in Ctsd+/− mice than in Ctsd+/+ mice (Figure 7E and 7F).

Figure 7. Effect of Ctsd haploinsufficiency on post-MI myocardial autophagic flux.

Three-months-old mice were subject to LAD ligation or sham surgery (2 males + 2 females for each group). A–D: LC3-II flux assays on 7 days (A and B) and 28 days (C and D) post-MI. Representative images (A, C) and pooled quantitative data (B, D) of western blot analyses for myocardial LC3-II are shown. E and F, Western blot analyses for cardiac p62. *p<0.05; $p<0.05 vs. the WT MI without BFA1 group.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have unveiled that myocardial CTSD-p, but not CTSB or CTSK proteins, is significantly upregulated in human end-stage HF resulting from IHD, which is also verified in mouse models of chronic MI. For the first time, the autophagic flux in post-MI hearts is directly measured and the results support the notion that post-MI myocardial autophagic activity is significantly increased. Through testing Ctsd−/− mice, we demonstrate that CTSD plays an indispensable role in the removal of autophagosomes in the heart. Moreover, we have established that MI-induced myocardial CTSD upregulation contributes to the enhanced autophagy and protects against post-MI ventricular remodeling and HF progression.

CTSD deficiency impairs myocardial autophagosome removal and causes restrictive cardiomyopathy

Lysosomes are responsible for the cargo removal in heterophagy and autophagy. As a major lysosomal aspartyl protease, CTSD is expected to play an important role in lysosomal proteolysis. Indeed, loss-of-function mutations of the CTSD gene are linked to human lysosome storage disease such as neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 10 (NCL10);26, 46 and mice with global or neuroectoderm-specific deletion of Ctsd display abnormalities that recapitulate main manifestations of human NCL10 disease.47 This, however, does not necessarily mean that CTSD is generally required for autophagic flux. There is evidence both for and against the notion that Ctsd is required for general autophagic flux. For example, increases in autophagosomes were observed in Ctsd null mouse brains,48, 49 which is consistent with impaired autophagosome removal but is also interpreted by some as evidence for induction of autophagy by Ctsd deficiency.49 On the other hand, inhibition of CTSD activity through overexpressing an inactive CTSD significantly decreased the degradation of endogenous α-synuclein but failed to mitigate autophagic flux in cultured SH-SY5Y cells;50 similarly, targeting Ctsd in mouse pancreatic acinar cells was reported to have no effect on autophagic activity.51 To our best knowledge, no reported study had performed a definitive autophagic flux assay on any organ/tissue of the Ctsd null mice. Using the well-accepted LC3-II flux assay, we have found that at the baseline condition, myocardial autophagic flux is not discernibly altered in Ctsd+/− mice but is significantly impaired in Ctsd−/− mice due to defective removal of autophagosomes as evidenced by accumulation of LC3-II at baseline and failure of BFA1-mediated lysosomal inhibition to increase LC3-II (Figure 2). Notably, Ctsd deficiency led to increases in CTSB, lysosome associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1), and LAMP2 proteins in the heart (Supplementary Figure X), which is in agreement with reports for other tissues/organs,44, 51 but these presumably compensatory responses apparently fail to effectively compensate for Ctsd deficiency, demonstrating that Ctsd is indispensable for autophagosome removal in myocardium.

The autophagic impairment caused by Ctsd deficiency is not harmless to the heart as we have detected restrictive cardiomyopathy in Ctsd−/− mice as reflected by reduced end diastolic volume and stroke volume with preserved EF and FS, in absence of cardiac hypertrophy (Figure 3).

Myocardial CTSD-p is increased in IHD

Serum CTSD proteins or activity were always higher in post-MI humans than age-matched controls.33, 52 As an alternate to renin, the increased CTSD may catalyze angiotensin II formation which is known to promote post-MI maladaptive cardiac remodeling.52 However, post-MI patients with major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) showed a lower average serum CTSD activity than those without MACE during a 6-month follow-up.33 It was unclear whether the post-MI increases in serum CTSD was accompanied by a reciprocal decrease of myocardial CTSD; now our results indicate this is very unlikely because we found significant increases in myocardial CTSD-p with CTSD-m unchanged in humans with IHD (Figure 1A~1C). This IHD-associated change is also sharply different from what was reported for human DCM which showed a marked CTSD-m reduction,32 but it is recapitulated in post-MI mouse hearts (Figure 1D~1F). In mice, myocardial CTSD-p proteins were increased throughout the first 4 weeks post-MI but CTSD-m, which was elevated at 1 and 2 weeks post-MI, returned to the sham control level at 4 weeks post-MI (Figure 4E). Notably, myocardial CTSB was markedly increased while mature CTSK was decreased at 7 days post-MI but neither was altered at 28 days post-MI in mice, which is consistent with the results from explanted human hearts with IHD. These findings indicate that cardiac changes of cathepsins during IHD are isoform-dependent and the change of individual isoforms (e.g., CTSD and CTSK) in the failing hearts is etiology-specific as myocardial CTSD was shown to decrease and CTSK to increase in human HF resulting from idiopathic DCM.16, 32

MI-induced CTSD upregulation promotes autophagic flux and protects against cardiac remodeling and malfunction

Here we have determined for the first time the effect of blocking CTSD upregulation on the progression of post-MI cardiac remodeling and HF. The MI-induced increases in myocardial CTSD proteins were completely prevented by Ctsd heterozygous knockout (Figure 5), which exacerbated post-MI LV chamber dilatation, decreases in EF and FS (Figure 6), the depression of LV contractile and relaxation function and cardiac output (Table 1), and pulmonary congestion and increased scar size (Figure 5). These results compellingly demonstrate that MI-induced CTSD upregulation confers protection against post-MI cardiac remodeling and malfunction.

Several previous studies have shown increases in autophagosome abundance in ischemic myocardium;30, 31, 45 here our LC3-II flux assay results (Figure 4) reveal explicitly for the first time that the increases are indeed caused by autophagic activation. Increased expression of CTSD was frequently used as an evidence of enhanced autophagy;29–31 however, the role of CTSD upregulation in promoting autophagy in diseased hearts has not been established until the present study. Blocking CTSD upregulation via Ctsd haploinsufficiency abolished the post-MI increase of myocardial autophagic flux via limiting the removal of autophagosomes (Figure 7), demonstrating that the CTSD upregulation is indispensable to increasing autophagic flux in post-MI hearts.

Studies manipulating cardiac autophagy have overwhelmingly shown a protective role for increased autophagy against myocardial ischemic injury and post-MI remodeling likely via promoting protein and organelle quality control.30, 31, 45 Taken together, our data indicate that IHD-induced upregulation of myocardial CTSD is critically adaptive and this protection is at least in part through promoting myocardial macroautophagy. Conceivably, it is likely that CTSD upregulation could also enhance other aspects of lysosomal function (e.g., heterophagy and other forms of autophagy) but that remains to be tested in the future.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

What’s new?

Myocardial levels of lysosomal protease cathepsin D (CTSD), but not cathepsin B or K, were increased in explanted failing human hearts with ischemic heart disease and these changes were recapitulated in a chronic myocardial infarction mouse model.

Through global knockout of the Ctsd gene, we showed that CTSD deficiency impairs myocardial autophagy and causes restrictive cardiomyopathy in mice.

Autophagic activity is increased in the post-MI hearts and this increase is associated with an upregulation of CTSD.

Preventing the heart from upregulating CTSD during MI exacerbates adverse cardiac remodeling and dysfunction in mice.

What are the clinical implications?

Lysosomal dysfunction is implicated in human heart failure due to ischemic disease.

Cathepsins are the proteases responsible for protein degradation in lysosomes.

Deficiency of cathepsin D, found in explanted heart from patients with advanced ischemic heart disease, was shown to contribute to adverse myocardial remodeling in a mouse model.

Our findings suggest that decreases in CTSD activity would be detrimental in ischemic heart disease.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This work is supported in part by NIH grants HL072166, HL085629, HL131667 (to XW) and HL111480 (to FL) and by a National Natural Science Foundation of China grant # 81570278-H0203 (to XW).

We thank Dr. Lisa McFadden for assistance in statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Wang X, Robbins J. Proteasomal and lysosomal protein degradation and heart disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;71:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lavandero S, Chiong M, Rothermel BA, Hill JA. Autophagy in cardiovascular biology. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:55–64. doi: 10.1172/JCI73943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ren J, Taegtmeyer H. Too much or not enough of a good thing--The Janus faces of autophagy in cardiac fuel and protein homeostasis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;84:223–226. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Su H, Li J, Osinska H, Li F, Robbins J, Liu J, Wei N, Wang X. The COP9 signalosome is required for autophagy, proteasome-mediated proteolysis, and cardiomyocyte survival in adult mice. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:1049–1057. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng Q, Su H, Ranek MJ, Wang X. Autophagy and p62 in cardiac proteinopathy. Circ Res. 2011;109:296–308. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.244707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Su H, Li F, Ranek MJ, Wei N, Wang X. COP9 signalosome regulates autophagosome maturation. Circulation. 2011;124:2117–2128. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.048934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li DL, Wang ZV, Ding G, Tan W, Luo X, Criollo A, Xie M, Jiang N, May H, Kyrychenko V, Schneider JW, Gillette TG, Hill JA. Doxorubicin Blocks Cardiomyocyte Autophagic Flux by Inhibiting Lysosome Acidification. Circulation. 2016;133:1668–1687. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma X, Liu H, Foyil SR, Godar RJ, Weinheimer CJ, Hill JA, Diwan A. Impaired autophagosome clearance contributes to cardiomyocyte death in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation. 2012;125:3170–3181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.041814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qin Q, Qu C, Niu T, Zang H, Qi L, Lyu L, Wang X, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti P, Janicki JS, Wang XL, Cui T. Nrf2-Mediated Cardiac Maladaptive Remodeling and Dysfunction in a Setting of Autophagy Insufficiency. Hypertension. 2016;67:107–117. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gottlieb RA, Andres AM, Sin J, Taylor DP. Untangling autophagy measurements: all fluxed up. Circ Res. 2015;116:504–514. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakai A, Yamaguchi O, Takeda T, Higuchi Y, Hikoso S, Taniike M, Omiya S, Mizote I, Matsumura Y, Asahi M, Nishida K, Hori M, Mizushima N, Otsu K. The role of autophagy in cardiomyocytes in the basal state and in response to hemodynamic stress. Nat Med. 2007;13:619–624. doi: 10.1038/nm1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turk V, Stoka V, Vasiljeva O, Renko M, Sun T, Turk B, Turk D. Cysteine cathepsins: from structure, function and regulation to new frontiers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1824:68–88. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun M, Ouzounian M, de Couto G, Chen M, Yan R, Fukuoka M, Li G, Moon M, Liu Y, Gramolini A, Wells GJ, Liu PP. Cathepsin-L ameliorates cardiac hypertrophy through activation of the autophagy-lysosomal dependent protein processing pathways. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000191. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun M, Chen M, Liu Y, Fukuoka M, Zhou K, Li G, Dawood F, Gramolini A, Liu PP. Cathepsin-L contributes to cardiac repair and remodelling post-infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;89:374–383. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu QQ, Xu M, Yuan Y, Li FF, Yang Z, Liu Y, Zhou MQ, Bian ZY, Deng W, Gao L, Li H, Tang QZ. Cathepsin B deficiency attenuates cardiac remodeling in response to pressure overload via TNF-alpha/ASK1/JNK pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;308:H1143–1154. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00601.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hua Y, Xu X, Shi GP, Chicco AJ, Ren J, Nair S. Cathepsin K knockout alleviates pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertension. 2013;61:1184–1192. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hua Y, Robinson TJ, Cao Y, Shi GP, Ren J, Nair S. Cathepsin K knockout alleviates aging-induced cardiac dysfunction. Aging Cell. 2015;14:345–351. doi: 10.1111/acel.12276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hua Y, Zhang Y, Dolence J, Shi GP, Ren J, Nair S. Cathepsin K knockout mitigates high-fat diet-induced cardiac hypertrophy and contractile dysfunction. Diabetes. 2013;62:498–509. doi: 10.2337/db12-0350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasilik A, Neufeld EF. Biosynthesis of lysosomal enzymes in fibroblasts. Synthesis as precursors of higher molecular weight. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:4937–4945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benes P, Vetvicka V, Fusek M. Cathepsin D--many functions of one aspartic protease. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;68:12–28. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saftig P, Hetman M, Schmahl W, Weber K, Heine L, Mossmann H, Koster A, Hess B, Evers M, von Figura K, et al. Mice deficient for the lysosomal proteinase cathepsin D exhibit progressive atrophy of the intestinal mucosa and profound destruction of lymphoid cells. EMBO J. 1995;14:3599–3608. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conus S, Perozzo R, Reinheckel T, Peters C, Scapozza L, Yousefi S, Simon HU. Caspase-8 is activated by cathepsin D initiating neutrophil apoptosis during the resolution of inflammation. J Exp Med. 2008;205:685–698. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conus S, Pop C, Snipas SJ, Salvesen GS, Simon HU. Cathepsin D primes caspase-8 activation by multiple intra-chain proteolysis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:21142–21151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.306399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laurent-Matha V, Huesgen PF, Masson O, Derocq D, Prebois C, Gary-Bobo M, Lecaille F, Rebiere B, Meurice G, Orear C, Hollingsworth RE, Abrahamson M, Lalmanach G, Overall CM, Liaudet-Coopman E. Proteolysis of cystatin C by cathepsin D in the breast cancer microenvironment. FASEB J. 2012;26:5172–5181. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-205229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vashishta A, Ohri SS, Vetvicka V. Pleiotropic effects of cathepsin D. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2009;9:385–391. doi: 10.2174/187153009789839174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Domenico F, Tramutola A, Perluigi M. Cathepsin D as a therapeutic target in Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2016;20:1393–1395. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2016.1252334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koch S, Scifo E, Rokka A, Trippner P, Lindfors M, Korhonen R, Corthals GL, Virtanen I, Lalowski M, Tyynela J. Cathepsin D deficiency induces cytoskeletal changes and affects cell migration pathways in the brain. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;50:107–119. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Comitato A, Sanges D, Rossi A, Humphries MM, Marigo V. Activation of Bax in three models of retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:3555–3562. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-13917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu H, Tannous P, Johnstone JL, Kong Y, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, Le V, Levine B, Rothermel BA, Hill JA. Cardiac autophagy is a maladaptive response to hemodynamic stress. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1782–1793. doi: 10.1172/JCI27523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yan L, Vatner DE, Kim SJ, Ge H, Masurekar M, Massover WH, Yang G, Matsui Y, Sadoshima J, Vatner SF. Autophagy in chronically ischemic myocardium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13807–13812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506843102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanamori H, Takemura G, Goto K, Maruyama R, Tsujimoto A, Ogino A, Takeyama T, Kawaguchi T, Watanabe T, Fujiwara T, Fujiwara H, Seishima M, Minatoguchi S. The role of autophagy emerging in postinfarction cardiac remodelling. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;91:330–339. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kostin S, Pool L, Elsasser A, Hein S, Drexler HC, Arnon E, Hayakawa Y, Zimmermann R, Bauer E, Klovekorn WP, Schaper J. Myocytes die by multiple mechanisms in failing human hearts. Circ Res. 2003;92:715–724. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000067471.95890.5C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamac AH, Sevgili E, Kucukbuzcu S, Nasifov M, Ismailoglu Z, Kilic E, Ercan C, Jafarov P, Uyarel H, Bacaksiz A. Role of cathepsin D activation in major adverse cardiovascular events and new-onset heart failure after STEMI. Herz. 2015;40:912–920. doi: 10.1007/s00059-015-4311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lusis AJ. Atherosclerosis. Nature. 2000;407:233–241. doi: 10.1038/35025203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goncalves I, Hultman K, Duner P, Edsfeldt A, Hedblad B, Fredrikson GN, Bjorkbacka H, Nilsson J, Bengtsson E. High levels of cathepsin D and cystatin B are associated with increased risk of coronary events. Open Heart. 2016;3:e000353. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2015-000353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moallem SA, Nazemian F, Eliasi S, Alamdaran SA, Shamsara J, Mohammadpour AH. Correlation between cathepsin D serum concentration and carotid intima-media thickness in hemodialysis patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2011;43:841–848. doi: 10.1007/s11255-010-9729-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ozkayar N, Piskinpasa S, Akyel F, Turgut D, Bulut M, Turhan T, Dede F. Relation between serum cathepsin D levels and endothelial dysfunction in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nefrologia. 2015;35:72–79. doi: 10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2014.Oct.12609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hou N, Ye B, Li X, Margulies KB, Xu H, Wang X, Li F. Transcription Factor 7-like 2 Mediates Canonical Wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling and c-Myc Upregulation in Heart Failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9:e003010. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.116.003010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li J, Horak KM, Su H, Sanbe A, Robbins J, Wang X. Enhancement of proteasomal function protects against cardiac proteinopathy and ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3689–3700. doi: 10.1172/JCI45709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tian Z, Zheng H, Li J, Li Y, Su H, Wang X. Genetically induced moderate inhibition of the proteasome in cardiomyocytes exacerbates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Circ Res. 2012;111:532–542. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.270983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Su H, Li J, Menon S, Liu J, Kumarapeli AR, Wei N, Wang X. Perturbation of cullin deneddylation via conditional Csn8 ablation impairs the ubiquitin-proteasome system and causes cardiomyocyte necrosis and dilated cardiomyopathy in mice. Circ Res. 2011;108:40–50. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.230607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takagawa J, Zhang Y, Wong ML, Sievers RE, Kapasi NK, Wang Y, Yeghiazarians Y, Lee RJ, Grossman W, Springer ML. Myocardial infarct size measurement in the mouse chronic infarction model: comparison of area- and length-based approaches. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2007;102:2104–2111. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00033.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamamoto A, Tagawa Y, Yoshimori T, Moriyama Y, Masaki R, Tashiro Y. Bafilomycin A1 prevents maturation of autophagic vacuoles by inhibiting fusion between autophagosomes and lysosomes in rat hepatoma cell line, H-4-II-E cells. Cell Struct Funct. 1998;23:33–42. doi: 10.1247/csf.23.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qiao L, Hamamichi S, Caldwell KA, Caldwell GA, Yacoubian TA, Wilson S, Xie ZL, Speake LD, Parks R, Crabtree D, Liang Q, Crimmins S, Schneider L, Uchiyama Y, Iwatsubo T, Zhou Y, Peng L, Lu Y, Standaert DG, Walls KC, Shacka JJ, Roth KA, Zhang J. Lysosomal enzyme cathepsin D protects against alpha-synuclein aggregation and toxicity. Mol Brain. 2008;1:17. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-1-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsui Y, Takagi H, Qu X, Abdellatif M, Sakoda H, Asano T, Levine B, Sadoshima J. Distinct roles of autophagy in the heart during ischemia and reperfusion: roles of AMP-activated protein kinase and Beclin 1 in mediating autophagy. Circ Res. 2007;100:914–922. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000261924.76669.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mole SE, Cotman SL. Genetics of the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses (Batten disease) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852:2237–2241. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ketscher A, Ketterer S, Dollwet-Mack S, Reif U, Reinheckel T. Neuroectoderm-specific deletion of cathepsin D in mice models human inherited neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 10. Biochimie. 2016;122:219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koike M, Nakanishi H, Saftig P, Ezaki J, Isahara K, Ohsawa Y, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Watanabe T, Waguri S, Kametaka S, Shibata M, Yamamoto K, Kominami E, Peters C, von Figura K, Uchiyama Y. Cathepsin D deficiency induces lysosomal storage with ceroid lipofuscin in mouse CNS neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6898–6906. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-06898.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koike M, Shibata M, Waguri S, Yoshimura K, Tanida I, Kominami E, Gotow T, Peters C, von Figura K, Mizushima N, Saftig P, Uchiyama Y. Participation of autophagy in storage of lysosomes in neurons from mouse models of neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinoses (Batten disease) Am J Pathol. 2005;167:1713–1728. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61253-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crabtree D, Dodson M, Ouyang X, Boyer-Guittaut M, Liang Q, Ballestas ME, Fineberg N, Zhang J. Over-expression of an inactive mutant cathepsin D increases endogenous alpha-synuclein and cathepsin B activity in SH-SY5Y cells. J Neurochem. 2014;128:950–961. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mehanna S, Suzuki C, Shibata M, Sunabori T, Imanaka T, Araki K, Yamamura K, Uchiyama Y, Ohmuraya M. Cathepsin D in pancreatic acinar cells is implicated in cathepsin B and L degradation, but not in autophagic activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;469:405–411. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Naseem RH, Hedegard W, Henry TD, Lessard J, Sutter K, Katz SA. Plasma cathepsin D isoforms and their active metabolites increase after myocardial infarction and contribute to plasma renin activity. Basic Res Cardiol. 2005;100:139–146. doi: 10.1007/s00395-004-0499-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.