Abstract

Introduction

Zhi Sou San (ZSS), a traditional Chinese prescription, has been widely applied in treating cough. The purpose of this meta-analysis was to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of ZSS for cough.

Methods

We searched relevant articles up to 5 March 2017 in seven electronic databases: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, PubMed, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Cqvip Database (VIP), China Biology Medicine disc (CBM), and Wanfang Data. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were eligible, regardless of blinding. The primary outcome was the total effective rate.

Results

Forty-six RCTs with a total of 4007 participants were identified. Compared with western medicine, ZSS significantly improved the total effective rate (OR: 4.45; 95% CI: 3.62–5.47) and the pulmonary function in terms of FEV1 (OR: 0.35; 95% CI: 0.24–0.46) and decreased the adverse reactions (OR: 0.05; 95% CI: 0.02–0.01) and the recurrence rate (OR: 0.30; 95% CI: 0.16–0.57). However, there was no significant improvement in the cough symptom score comparing ZSS with western medicine.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis shows that ZSS has significant additional benefits and relative safety in treating cough. However, more rigorously designed investigations and studies, with large sample sizes, are needed because of the methodological flaws and low quality of the included trials in this meta-analysis.

1. Introduction

Cough is the most common symptom among individuals seeking medical care. According to the duration, cough is divided into three types: acute, subacute, and chronic [1]. Acute cough (less than 3 weeks in duration) is the most predominant symptom of common cold or acute viral upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) [2, 3]. Acute cough from the common cold is usually transient and minor, but it may be life-threatening when it is caused by a serious illness [2]. Dyspnea, tachypnea, thoracic pain, hemoptysis, a severely worsened general state, and changes in vital signs are the major danger signs of acute cough [4]. Cough lasting from 3 to 8 weeks is categorized as subacute cough [5]. Postinfectious cough (PIC) is the most common cause of subacute cough [5]. Chronic cough is described as a cough that persisted for more than 8 weeks in adults [6] and more than 4 weeks in children (age < 15 years) [7]. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), asthma syndromes, smoker's cough, nonasthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis, and upper airway cough syndrome (UACS) associated with postnasal drip (rhinitis or rhinosinusitis) are the most common conditions associated with chronic cough in adults who are nonsmokers and are not receiving therapy with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor [6, 8–10]. Unexplained chronic cough should be diagnosed as chronic cough with no etiology identified after evaluation and supervised therapeutic trial(s) that follow published best-practice guidelines [11].

Recent guidelines have attempted to provide directions in the treatment and management of cough. Patients with acute cough associated with the common cold can be treated with first-generation antihistamine/decongestant (A/D) preparation, expectorants, or mucolytics [3, 8]. Acute cough accompanying a cold or acute bronchitis/sinusitis usually resolves without any specific medicinal treatment. Any antibiotic treatment of uncomplicated upper respiratory tract infections should be avoided according to the guideline [4]. Although the inhaled ipratropium or inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) may be useful for PIC, the optimal treatment is not known [8, 57]. Cough variant asthma (CVA) should be initially treated with inhaled bronchodilators and ICSs [8]. Dietary and lifestyle modification, acid suppression therapy, and prokinetic therapy are recommended in patients with chronic cough due to GERD [8]. Current recommendations on managing UACS include A/D or intranasal corticosteroids [6]. Multimodality speech pathology therapy and therapeutic trial of gabapentin are recommended for adults with unexplained chronic cough [11].

ZSS, a formula originating from Qing Dynasty, is commonly used in treating cough nowadays. Tan et al. [58], Zhang [59], and Meng et al. [60], respectively, reported that ZSS is the most frequently used formula in the treatment of PIC and CVA. ZSS is composed of seven herbs: Platycodon grandiflorum, Fine Leaf Schizonepeta herb, Tatarian Aster root, Sessile Stemona root/Japanese Stemona root/Tuber Stemona root, Willowleaf Swallowwort Rhizome, tangerine peel, and liquorice root. According to the theory of TCM, ZSS could loose the evil Qi and calm the lung Qi. Compared to its counterparts, ZSS is peaceful and gentle, not too cold or hot.

Modified Zhi Sou San (MZSS) could improve the symptoms of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in rats of northwest China with cold dryness syndrome and delay the velocity of decreased lung function [61]. An experiment showed that the antiasthmatic mechanisms of MZSS were related to its significant reduction in contents of endothelin-1 and nitric oxide, eosinophilia, and the damage of lung tissue [62].

Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses showed that ZSS might be effective in treating diseases-induced cough (including PIC, CVA, and laryngeal cough) [63–65]. Jing et al. reported that MZSS or MZSS combined with western medicine had better safety and efficacy than western medicine alone in treating PIC [63]. ZSS or ZSS combined with western medicine had superior effect and lower recurrence rate than western medicine alone in treating CVA [64]. Wang et al. reported that, compared with western medicine, ZSS had good efficacy and less adverse reactions in treating laryngeal cough [65]. Although the aforementioned reviews and meta-analyses elaborated that ZSS was more effective and safe than western medicine in treating diseases-induced cough, whether ZSS is the alternative medicine in treating cough is not confirmed. More trials and evidences are needed. So this meta-analysis was aimed at summarizing and evaluating the evidence from RCTs and determining whether ZSS is more effective and safer than western medicine in the treatment of cough.

2. Methods

2.1. Research Protocol

This meta-analysis is reported in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.

2.2. Databases and Search Strategies

We searched relevant articles up to 5 March 2017 in seven electronic databases: CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and PubMed in English and CNKI, VIP, CBM, and Wanfang Data in Chinese. The search terms used for databases were as follows: (cough or cough∗) for cough AND (zhisousan or zhisou san or zhisou powder) for ZSS AND randomized or controlled or clinical research.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

Studies included had to meet the following criteria: (a) types of studies: any RCTs with ZSS or MZSS administrated orally in patients with cough were eligible, regardless of blinding; (b) types of participants: any patients diagnosed with cough regardless of sex, age, country, or underlying disease were included; (c) types of interventions: any variants of ZSS regardless of the herbs in the ZSS archetype replaced, added, or removed were included; the control group was taking the western medicine; (d) types of outcomes: the primary outcome was the total effective rate (clinical cure rate plus obvious cure rate plus showing effective rate). The clinical efficacy classified as clinical cure, obvious cure, and showing effective and not effective rate was based on the guiding principle of clinical research on new drugs of TCM and/or the diagnostic criteria of TCM syndrome. The secondary outcomes were the score of TCM symptom, cough symptom score (such as cough diary or visual analog scale), the adverse reactions, the pulmonary function test results, and the recurrence rate.

2.4. Study Selection and Data Extraction

Two independent investigators (Ningchang Cheng and Jia Zhu) screened the titles and abstracts of the searched articles. The trials obviously not meeting the inclusion criteria were excluded. We emailed the corresponding authors of the trials which possibly meet the inclusion criteria to ensure that the included trials were RCTs. Any disagreements were dissolved by consensus and discussions. All articles included were judged by the third reviewer (Pinpin Ding). Data extracted included the authors, year of publication, country, sample size, participants (mean age, cough duration), cough inducing disease, details of ZSS interventions, details of control inventions, treatment duration, outcome measurements, and adverse events [66].

2.5. Assessment of Risk of Bias

According to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (version 5.0.2), the risk of bias was assessed in seven domains, such as random sequence generation and allocation concealment for selection bias, blinding of participants and personnel for performance bias, blinding of outcome assessment for detection bias, incomplete outcome data for attrition bias, selective outcome reporting for reporting bias, and other sources of bias.

2.6. Data Analysis

Review Manager Software (Version 5.3, Copenhagen, the Nordic Cochrane Centre, the Cochrane Collaboration, 2014) was used for data analysis. Heterogeneity between similar studies is evaluated by chi-square test and I2 statistic. There is moderate heterogeneity between studies, if P < 0.05 and I2 > 50%, and sensitivity analysis is needed. The enumeration data is evaluated as dichotomous data and expressed as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). The measurement data is evaluated as continuous data and expressed as mean difference (MD) with 95% CI. Statistical significant difference was considered as P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

We identified 905 articles through electronic searching. After duplicates were removed, 263 records were screened. The full texts of 141 studies were assessed for eligibility after screening the titles and abstracts. 95 studies were excluded with reasons of full text being unavailable, not being RCTs, the controlled group not taking western medicine, and not relevant trials. Finally, 46 studies [12–56, 67] were included in this meta-analysis. A flowchart in the form of PRISMA is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of literature searching.

All the included trials originated from China and were published from 2004 to 2016. The total number of participants analyzed in the meta-analysis was 4007, of which 2077 received ZSS or MZSS, while 1930 received western medicine alone. The baseline characteristics of the included trials were shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the included trials.

| Author | Year | Country | Cough inducing disease | Sample size (I/C) | Intervention group | Control group | Age (years) (I/C) |

Cough duration (I/C) |

Intervention duration | Outcome measurements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dong [12] | 2014 | China | Postsurgical cough | 52/53 | ZSS | Gentamicin + α-chymotrypsin | 32–65 | NR | 3 d | ① |

| Cai [13] | 2013 | China | PIC | 36/36 | MZSS | Ketotifen or ambroxol | 6–15/7–19 | NR | 5 d | ① |

| Cai [14] | 2011 | China | PIC | 30/30 | MZSS | Meptin + ketotifen + azithromycin | 18–60/21–55 | 21–55 d/22–54 d | 7 d | ① |

| Cao [15] | 2011 | China | PIC | 30/27 | ZSS | Cephalexin + compound guaiacol potassium oral solution | 3–8/4–10 | 15 d–1 y/10 d–10 m | 7 d | ① |

| Jin [16] | 2016 | China | PIC | 40/40 | MZSS | Pentoxyverine + loratadine | 50.08 ± 7.82/49.85 ± 7.85 | 24.53 ± 8.40 d/23.88 ± 7.90 d | 10 d | ① |

| Ju [17] | 2010 | China | PIC | 56/56 | MZSS | Chlorphenamine maleate | 37.5l ± 9.47/40.18 ± 10.56 | 40.5 ± 11.5 d/41.2 ± 12.7 d | 15 d | ① + ② |

| Kan [18] | 2010 | China | PIC | 30/30 | MZSS | Dextromethorphan + chlorphenamine maleate | 45.47 ± 8.36/44.59 ± 8.72 | 4.8 ± 1.2 wk/4.6 ± 1.5 wk | 10 d | ① |

| Kan [19] | 2011 | China | PIC | 33/32 | MZSS | Roxithromycin id | 2–10/2–10 | 4 wk–3 m/4 wk–3 m | 14 d | ① |

| Li [20] | 2013 | China | PIC | 30/30 | MZSS | Asmeton | 32.19 ± 5.86/33.35 ± 5.72 | 36.6 ± 6.9 d/33.2 ± 7.5 d | 7 d | ① + ③ |

| Liang [21] | 2014 | China | PIC | 84/84 | MZSS | Pentoxyverine | 32.1 ± 1.7/31.9 ± 2.4 | 14.3 ± 2.0 d/14.0 ± 1.9 d | NR | ① + ③ |

| Liu and Qiu [22] | 2012 | China | PIC | 38/40 | MZSS | Pentoxyverine + chlorphenamine maleate | 19–53/18–55 | 3–8 wk | NR | ① + ③ |

| Liu [23] | 2014 | China | PIC | 68/64 | MZSS | Ketotifen + carbetapentane citrate | 36.0 ± 6.8/38.0 ± 7.5 | 33.0 ± 7.5 d/35.0 ± 8.5 d | 10 d | ① |

| Lu [24] | 2012 | China | PIC | 43/43 | MZSS | Ketotifen + meptin + azithromycin | 34.3 ± 1.4 | 38 ± 2.1 d | 7 d | ① |

| Qiu [25] | 2012 | China | PIC | 28/28 | MZSS | Chlorphenamine maleate + cartussin | 22–55/20–60 | 19–49 d/23–46 d | 15 d | ① |

| Qiu [26] | 2011 | China | PIC | 82/78 | MZSS | Dextromethorphan + loratadine | 33.5 ± 8.6/34.3 ± 8.8 | 18 ± 3.0 d/17.6 ± 2.0 d | 7 d | ① + ③ |

| Qiu [27] | 2012 | China | PIC | 35/30 | MZSS | Compound pholcodine syrup + asmeton + azithromycin | 14–65/15–65 | NR | 3 d | ① |

| Sun [28] | 2011 | China | PIC | 58/52 | MZSS | Chlorpheniramine maleate + methyl bromide | 19–57/20–58 | 14–40 d/16–41 d | 7 d | ① |

| Tao [29] | 2011 | China | PIC | 30/30 | MZSS | Pseudoephedrine hydrochloride sustained release capsules | 40.2 ± 8.7/39.5 ± 7.5 | 40.5 ± 13 d/42.8 ± 10.0 d | 7 d | ① + ② |

| Zhu [30] | 2010 | China | PIC | 62/30 | MZSS | Azithromycin | 2 m–13/5 m–13 | 2–4 d/1–5 d | 3 wk | ① |

| Chen [31] | 2004 | China | Laryngeal cough | 39/39 | MZSS | Roxithromycin id + Zhikelu | 5–87/7–82 | 5 d–2 y/3 d–1.5 y | 5 d | ① |

| Fang [32] | 2014 | China | Laryngeal cough | 43/43 | MZSS | Setastine + carbetapentane citrate + new bromide | 40/41 | 3–12 wk/3–12 wk | 14 d | ① |

| Hu [33] | 2013 | China | Laryngeal cough | 59/54 | MZSS | Budesonide | 34–63/32–64 | 3–8 wk/3–7.3 wk | 7 d | ① + ⑤ |

| Huang [34] | 2013 | China | Laryngeal cough | 60/60 | MZSS | Cefuroxime axetil + phenergan syrup | 16–64/17–65 | 7 d–3 m/7 d–3 m | 10 d | ① + ③ + ⑤ |

| Liu [35] | 2004 | China | Laryngeal cough | 72/38 | MZSS | Amoxicillin or cefradine + phenergan cough syrup | 31.3 ± 2.1/30.1 ± 2.3 | 42 ± 2.3 d/43.3 ± 6.7 d | 4 d | ① |

| Gong [36] | 2007 | China | CVA | 40/40 | MZSS | Ketotifen + doxofylline + salbutamol aerosol | 41.3 ± 10.3/38.5 ± 11.8 | 2–36 m/2–30 m | 28 d | ① + ④ |

| Lu [37] | 2007 | China | CVA | 35/34 | MZSS | Terbutaline + cetirizine | 9.6/9.2 | 1.3 m/1.4 m | 14 d | ① |

| Liu [35] | 2012 | China | CVA | 28/25 | MZSS | Shah Mette Lo fluticasone propionate | 43.79 ± 12.58/42.16 ± 10.77 | 3.42 ± 2.17 m/3.55 ± 2.29 m | 14 d | ① + ② |

| Qu [38] | 2006 | China | CVA | 30/30 | MZSS | Terbutaline | 38.2 ± 12.5/40.3 ± 13.2 | 7.5 ± 8.5 m/8.0 ± 7.0 m | 30 d | ① + ④ |

| Tao [39] | 2014 | China | CVA | 55/55 | MZSS | Montelukast sodium + budesonide aerosol | 2–11/2.5–12 | 3–33 m/4–36 m | 4 wk | ① |

| Wang [40] | 2011 | China | CVA | 60/60 | MZSS | Conventional treatment for cough | 2–9/2.5–10 | NR | 10 d | ① |

| Yu et al. [41] | 2016 | China | CVA | 52/52 | MZSS | Shah Mette Lo fluticasone powder | 40.9 ± 6.8/41.5 ± 7.2 | 8.5 ± 2.2 m/8.2 ± 2.4 m | 30 d | ① + ② + ④ |

| Zhang [42] | 2009 | China | CVA | 30/30 | MZSS | Ceftazidime + dexamethasone | 2–66 | NR | 14 d | ① + ② |

| Shao [43] | 2004 | China | Cough | 60/48 | MZSS | Cefradine | 14–66/12–62 | NR | 14 d | ① |

| Cai [44] | 2011 | China | Chronic cough | 24/24 | MZSS | Conventional treatment for cough | 26–70/20–65 | 8–36 wk/10–42 wk | 14 d | ① |

| Dai et al. [45] | 2015 | China | Chronic cough | 26/26 | MZSS | Desloratadine + ambroxol | 37.83 ± 10.43/36.40 ± 11.89 | 28.55 ± 26.71 wk/34.73 ± 24.17 wk | 14 d | ① |

| Huang [46] | 2014 | China | Chronic cough | 45/45 | MZSS | Chlorphenamine + aminophylline + ambroxol | 24–75 | 8 wk–2 y | 14 d | ① + ③ |

| Qiao [47] | 2016 | China | Chronic cough | 40/40 | MZSS | Cefuroxime axetil + ambroxol + dextromethorphan | 54.6 ± 7.9 | 3.3 ± 1.6 y | 1 m | ① + ③ |

| Tao [48] | 2013 | China | Chronic cough | 40/40 | MZSS | Azithromycin + ambroxol | 20–76 | NR | 7 d | ① |

| Wang and Guo [49] | 2016 | China | Chronic cough | 50/50 | MZSS | Chlorpheniramine maleate + salbutamol + methyl bromide | 4.65 ± 1.94/5.46 ± 2.53 | NR | 7 d | ① |

| Yang [50] | 2015 | China | Chronic cough | 47/47 | MZSS | Asmeton | 41.6 ± 5.7 | 10.4 ± 1.9 | 7 d | ① + ③ |

| Ye [51] | 2009 | China | Chronic cough | 30/30 | MZSS | Asmeton | 19–46 | NR | 7 d | ① |

| Zhang [52] | 2016 | China | Chronic cough | 44/44 | MZSS | Ambroxol | 50 ± 2.96/51 ± 2.63 | NR | 14 d | ① + ⑤ |

| Dang and Yang [53] | 2008 | China | Allergic cough | 38/38 | MZSS | Ketotifen + aminophylline | 2–12/2–12 | 1–6.6 m/1–5.9 m | 7 d | ① |

| Zhang [54] | 2014 | China | Allergic cough | 25/25 | MZSS | Terbutaline | 6.25 ± 3.05/6.05 ± 3.12 | 8.09 ± 15.45 m/7.86 ± 15.36 m | 4 wk | ① + ③ |

| Hu [55] | 2015 | China | Acute cough | 60/60 | ZSS | Asmeton | 37 ± 11/36 ± 10 | 18 ± 6 d/16 ± 7 d | 14 d | ① |

| Huang [56] | 2011 | China | Acute cough | 80/40 | MZSS | Amoxicillin | 19–35/20–34 | 0.5–7 d/0.5–6.5 d | 3 d | ① |

y, year; m, month; wk, week; d, day; NR: not reported. Note. ① The total effective rate, ② cough symptom score, ③ the adverse reactions, ④ the pulmonary function test results, and ⑤ the recurrence rate.

In the final selected studies, postsurgical cough accounted for one study [12], cough accounted for one study [43], allergic cough accounted for two studies [53, 54], acute cough accounted for one study [56], laryngeal cough accounted for six studies [31–35, 55], CVA accounted for eight studies [36–42, 67], chronic cough accounted for nine studies [44–52], and PIC accounted for eighteen studies [13–30].

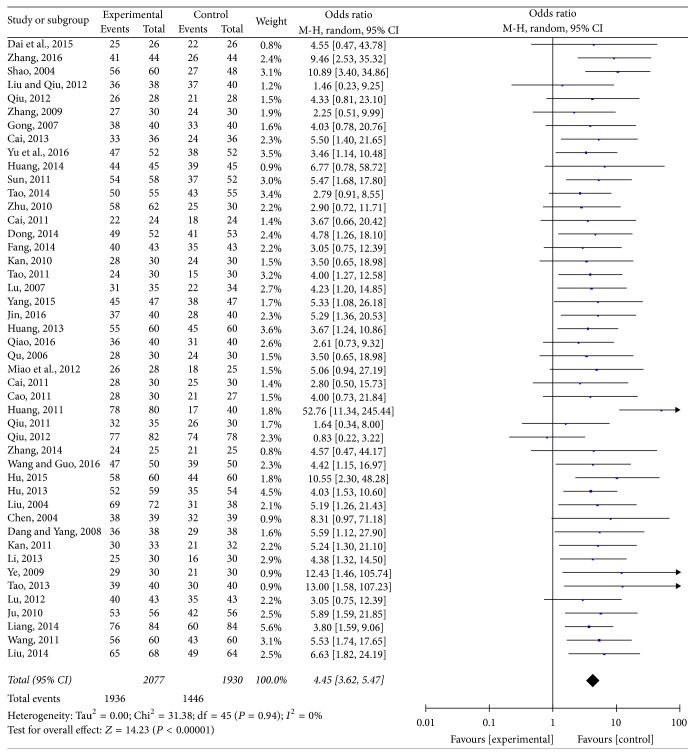

3.2. The Total Effective Rate

All trials finally selected reported data on total clinical response rate [12–56, 67]. As for the fact that there was no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%; P = 0.94), a random-effects model was applied (Figure 2). The meta-analysis showed that a significant improvement in the total effective rate (OR: 4.45; 95% CI: 3.62–5.47) was observed when comparing ZSS to western medicine alone.

Figure 2.

The effective rate comparing ZSS to western medicine alone.

3.3. Cough Symptom Score

Five trials reported data on cough symptom score [17, 29, 41, 42, 67]. After sensitivity analysis, a trial [17] was excluded. As for the fact that there was no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%; P = 0.53), the meta-analysis showed that there was no significant improvement in the cough symptom score (OR: −0.72; 95% CI: −0.79–−0.65).

3.4. The Adverse Reactions

Nine trials mentioned the adverse reactions as the secondary outcome [20–22, 26, 34, 46, 47, 50, 54]. As is shown in Figure 3, a random-effects model was applied; there was no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 43%; P = 0.09). The meta-analysis showed that a significant decrease in the adverse reactions (OR: 0.05; 95% CI: 0.02–0.01) was observed when comparing ZSS to western medicine alone.

Figure 3.

The adverse reactions comparing ZSS to western medicine alone.

3.5. The Pulmonary Function Test Results

Three trials provided data on the pulmonary function test results [36, 38, 41]. Two trials reported FEV1 (L) [38, 41]. The meta-analysis with random-effects model showed that ZSS significantly improved the pulmonary function in terms of FEV1 (I2 = 0%; P = 0.46; OR: 0.35; 95% CI: 0.24–0.46) in comparison to western medicine alone (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The pulmonary function test results comparing ZSS to western medicine alone.

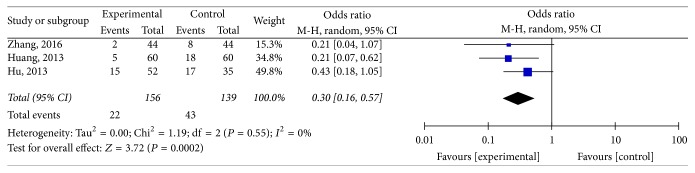

3.6. The Recurrence Rate

There were three studies that talked about the recurrence rate [33, 34, 52]. Results (Figure 5) indicated that ZSS obviously decreased the recurrence rate compared with western medicine (I2 = 0%; P = 0.55; OR: 0.30; 95% CI: 0.16–0.57).

Figure 5.

The recurrence rate comparing ZSS to western medicine alone.

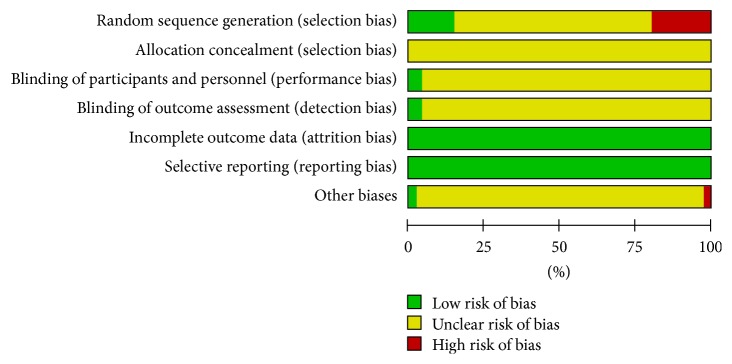

3.7. Assessing the Risk of Bias of the Included Studies

The risk of bias of the finally included trials was not low. The selection bias was high due to the fact that wrong methods were applied in random sequence generation. Because multiple studies failed in blinding of participant and outcome assessment, the performance and detection biases were high (Figures 6 and 7) (+ indicates low risk of bias, − indicates high risk of bias, and ? indicates unclear risk of bias).

Figure 6.

Risk of bias graph of the included trials.

Figure 7.

Risk of bias summary of the included trials.

4. Discussion

A wide variety of pharmacological agents have been used in treating cough, such as antibiotic, ketotifen, asmeton, dextromethorphan, and ICSs [68]. No matter what caused cough, those mentioned agents were broadly used in remedying cough. “Zhisou,” by its Chinese definition, means relieving cough. So ZSS is one formula that has the behavior of relieving cough and it is widely applied in China, Korea, and Japan. It is necessary and attractive to compare ZSS and western medicine commonly used in curing cough. This meta-analysis was aimed at evaluating the effect and safety between ZSS and aforementioned western medicines. However, we could not find any studies originating from Japan or Korea in those databases that we have searched. It may be due to the fact that the authors of this meta-analysis all come from China; they do not master Japanese language and Korean language.

As we know, this meta-analysis is the first one about using ZSS in treating cough. This meta-analysis included studies of a wide range of conditions, such as acute cough, chronic cough, PIC, and CVA. The main findings of this meta-analysis are as follows: ZSS significantly improved the total effective rate and the pulmonary function in terms of FEV1, ZSS decreased the adverse reactions and the recurrence rate compared with western medicine, and ZSS appeared to be safe, well-tolerant, and more effective in treating cough.

However, we should admit that several limitations exist concerning this study. Firstly and foremost, the sample sizes of RCTs were small and limited. So, it was difficult to find out the influence of contingency factors. Secondly, insufficient reporting of random sequence generation and allocation concealment were the major methodological flaws in most of the included trials, which could result in selection bias and decrease the reliability of the evidence. Thirdly, the overall methodological quality of included trials was low due to the lack of blinding of participants and personnel and outcome assessment. On the whole, the finally included studies failed to follow CONSORT guidelines for RCTs; the risk of bias assessment was assessed as high risk or unclear risk in a majority of the RCTs. Therefore, RCTs with high quality and large sample are required to be done in the future.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81473609).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Ningchang Cheng and Jia Zhu designed this study, interpreted the results, made the literature research, extracted data, performed the statistical analysis, and revised the manuscript. Pinpin Ding evaluated the quality of the included studies and drafted the manuscript.

References

- 1.Morice A. H., Fontana G. A., Belvisi M. G., et al. ERS guidelines on the assessment of cough. European Respiratory Journal. 2007;29(6):1256–1276. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00101006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irwin R. S. Guidelines for treating adults with acute cough. American Family Physician. 2007;75(4):476–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eccles R., Turner R. B., Dicpinigaitis P. V. Treatment of acute cough due to the common cold: multi-component, multi-symptom therapy is preferable to single-component, single-symptom therapy—a pro/con debate. Lung. 2016;194(1):15–20. doi: 10.1007/s00408-015-9808-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holzinger F., Beck S., Dini L., etal. The diagnosis and treatment of acute cough in adults. Deutsches Rzteblatt International. 2014;111(20):356–363. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwon N.-H., Oh M.-J., Min T.-H., Lee B.-J., Choi D.-C. Causes and clinical features of subacute cough. Chest. 2006;129(5):1142–1147. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.5.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGarvey L. P. A., Polley L., MacMahon J. Review series: chronic cough: common causes and current guidelines. Chronic Respiratory Disease. 2007;4(4):215–223. doi: 10.1177/1479972307084447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang A. B., Glomb W. B. Guidelines for evaluating chronic cough in pediatrics: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129(1) doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.260S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irwin R. S., et al. Diagnosis and management of cough executive summary: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129(1):p. 1S. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.1S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lahiri K. R., Landge A. A. Approach to chronic cough. Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2014;81(10):1027–1032. doi: 10.1007/s12098-014-1391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poulose V., Tiew P. Y., How C. H. Approaching chronic cough. Singapore Medical Journal. 2016;57(2):60–63. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2016028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Randel A. ACCP releases guideline for the treatment of unexplained chronic cough. American Family Physician. 2016;93(11):p. 950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong J. Clinical observation on treating cough after breast cancer surgery with general anesthesia with Zhisou San. Yunnan Journal of TCM. 2014;35(2):18–20. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai D. L. Check the observation of 50 cases of cough cough after cold treatment of Paris powder plus. China Medical Herald. 2013;14:350–350. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai Q. H. Treatment of 30 cases of post infectious cough with the combination of Sanao Decoction and Zhisou San. Journal of Practical Medicine. 2011;27(1):131–132. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao S. M. Treatment of 30 cases of infantile cough due to exogenous cough with Zhisou San. Henan Journal of TCM. 2011;31(2):173–173. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin L. L. Clinical observation on treating cough with modified Zhisou San. Guangming traditional Chinese Medicine. 2016;31(13):1897–1898. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ju Y. R. Treatment of 56 cases of cough with the combination of sanao decoction and zhisou san. Chinese Medicine Modern Distance Education of China. 2010;8(3):39–40. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kan J. Clinical observation on treating cough after cold with modified Zhisou San. Hubei Journal of TCM. 2010;32(6):41–42. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kan Y. Clinical observation on the treatment of chronic cough in children with modified Zhisou powder. Guiding Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy. 2011;17(4):44–46. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y. Clinical observation on treating 30 cases of post infectious cough with modified Zhisou San. Neimenggu Journal of TCM. 2013;32(17):13–14. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang Y. T. Clinical observation on treating post infectious cough with modified Zhisou San. Ningxia Medical Journal. 2014;36(11):1074–1075. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu C. G., Qiu S. L. Clinical observation on the treatment of 38 cases of cough after cold with the mixture of chuanxiongchatiao san and zhisou san. Journal of New Chinese Medicine. 2012;9:13–14. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Z. P. Clinical observation on treating cough after cold with modified Zhisou San. Chinese Manipulation Rehabilitation Medicine. 2014;8:131–132. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu Y. M. Clinical observation on treating cough after cold with the combination of Sanao Decoction and Zhisou San. Health Must-read. 2012;11(7):208–208. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qiu C. H. Treatment of 30 cases of post infectious cough with the combination of Sanao Decoction and Zhisou San. Shandong Journal of TCM. 2012;6:409–410. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qiu W. D. Clinical observation on treating cough after cold with modified Zhisou San. Journal of Guangxi TCM University. 2011;14(4):11–12. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qiu W. D. Treatment of 35 cases of post infectious cough with the combination of Sanao Decoction and Zhisou San. Chinese and Foreign Health Abstracts. 2012;9(21):407–407. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun H. H. Treatment of 58 cases of post infectious cough with modified Zhisou San. China Medical Herald. 2011;18(1):95–96. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tao J. Clinical observation on the treatment of post infectious cough with modified Zhisou powder. Chinese Journal of Modern Drug Application. 2011;5(15):6–7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu H. M. Clinical study on treatment of 62 cases of mycoplasma infection in children with modified Zhisou San. Academic Medicine Xuzhou. 2010;30(9):602–603. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen X. M. Treatment of 39 cases of laryngeal cough with Jiawei Zhishou San. Zhejiang Journal of TCM. 2004;39(10):431–431. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fang J. Treatment of 43 cases of laryngeal cough with Jiawei Zhishou San. Jiangsu Journal of TCM. 2014;46(9):33–34. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu X. H. Clinical observation on the treatment of laryngeal cough by Zhisou powder combined with yangyin qingfei decoction. Chinese Journal of Information on TCM. 2013;20(5):78–79. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang L. Y. Clinical observation on treating 60 cases of laryngeal cough with cough powder. Clinical Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2013;19:83–84. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu X. H. Clinical observation on the treatment of cough with Zhisou san due to cough and scattered. Guangxi Journal of TCM. 2004;27(2):27–28. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gong C. J. Effect of jiawei zhisousan on airway hyperresponsiveness in patients with cough variant asthma. Beijing Journal of TCM. 2007;26(3):147–149. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu K. H. Treatment of 35 cases of cough variant asthma with modified Zhisou San. Shanxi Journal of TCM. 2007;28(4):390–391. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qu N. N. Professor Ma Zhi's experience in treating cough variant asthma by addition and subtraction. Chinese Archives of TCM. 2006;24(2):212–213. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tao H. J. Observation on 55 cases of cough variant asthma in children treated with Dongxing Zhisousan. Journal of Practical Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2014;6:494–494. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Z. B. Treatment of 60 cases of cough variant asthma in children with the combination of Sanao Decoction and Zhisou San. Guangming Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2011;10:2049–2050. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu G. Q., et al. Clinical research on treating wind cold violating lung syndrome cough variant astluna with zhisousan decoction. World Chinese Medicine. 2016;11(1):58–61. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang C. H. Clinical observation on treatment by Jiawei Zhisou San of 30 cases of cough variant asthma in children with cough caused by wind evil. Beijing Journal of TCM. 2009;28(8):619–621. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shao C. D. Treatment on cough with modified Zhisousan. Shanxi Journal of TCM. 2004;25(12):1066–1067. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cai J. Treatment of 48 cases of chronic cough with jiawei zhishou san. China Medical Herald. 2011;1(24):328–328. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dai B., et al. Clinical observation on 26 cases of chronic cough treated by modified Zhisou powder. Hunan Journal of TCM. 2015;31(7):42–43. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang H. Analysis of curative effect and safety of the treatment of chronic cough with Zhisou San combined with Sanao Tang. Journal of Practical Chinese Medicine. 2014;18:182–183. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qiao M. F. Clinical analysis of the treatment of chronic cough with the combination of five kinds of decoction of Poria and Gansu. Guangming traditional Chinese Medicine. 2016;31(11):1529–1530. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tao Y. A. Clinical observation on treatment of 80 cases of chronic cough with Zhisou San. Henan Journal of TCM. 2013;b10:196–196. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang X., Guo N. Effect of Beilou Zhisou powder in the treatment of children with chronic cough. Journal of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine. 2016;8(3):319–321. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang K. J. Clinical observation on treatment of 43 cases of chronic cough with Zhisou San. Medical Information. 2015;25 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ye Y. Clinical observation on treatment of 60 cases of chronic cough with Zhisou San. China Medical Herald. 2009;6(29):86–86. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang B. Analysis of the curative effect of Chinese herbal medicine on chronic cough. Medicine. :218–218. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dang Y., Yang G. Treatment of 38 cases of allergic cough in children with the combination of sanao decoction and zhisou san. Henan Journal of TCM. 2008;28(12):85–86. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang W. R. Clinical study on the treatment of allergic cough with zhisou powder and modified allergic decoction. Neimenggu Journal of TCM. 2014;33(14):p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hu X. D. Clinical efficacy and safety analysis of traditional Chinese medicine for relieving cough. Chinese Medicine. 2015;10(8):1130–1132. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang S. Y. Treatment of 80 cases of upper respiratory tract infection in pregnant women with Jiawei Zhisousan. Chinese Journal of Ethnomedicine and Ethnopharmaey. 2011;20(1):121–121. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Braman S. S. Postinfectious cough: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129(1):138S–146S. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.138s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tan X. Y., et al. Literature research on treatment of cough after infection by traditional Chinese medicine. China Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy. 2012;12:3195–3197. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang X. Y. Characteristics of Cough Syndrome after Infection and Literature Review of TCM Treatment. Beijing University of TCM; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meng F. P., et al. Modern literature research on prescription prescription of Chinese medicine for asthma treatment based on Text Mining. China Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy. 2015;10:3490–3493. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gao Z. Effect of modified Zhisou powder on the lung function of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease model rats of northwest China cold dryness syndrome. China Medical Abstracts (Internal Medicine) 2014;34(3):p. 133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu N. Y., et al. Experimental study on treatment of allergic asthma guinea pigs with different fractions of Modified Zhisousan. Journal of Chinese Medicinal Materials. 2006;29(5):462–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jing J., et al. Zhisou san in treatting cough induced by infections based on randomized clinical trials meta-analysis. Chinese Journal of Experimental Traditional medical Formulae. 2013;19(16):343–348. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hu J. Q., et al. Evaluation of zhisousan in the treatment of cough variant asthma. China Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2015;30(3):333–336. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Y., et al. Meta-analysis of zhisou powder in the treatment of laryngeal cough. Asia-Pacific Tmditional Medicine. 2017;13(2) [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gagnier J. J., Boon H., Rochon P., Moher D., Barnes J., Bombardier C. Reporting randomized, controlled trials of herbal interventions: an elaborated CONSORT statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;144(5):364–367. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-5-200603070-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miao Q., et al. Jiawei zhisou san in treatment of twenty-eight cases with cough variant asthma. Chinese Journal of Experimental Traditional Medical Formulae. 2012;18(5):227–230. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yancy W. S., Jr., McCrory D. C., Coeytaux R. R., et al. Efficacy and tolerability of treatments for chronic cough: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2013;144(6):1827–1838. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]