Abstract

Background

To date there has been limited success with childhood obesity prevention interventions. This may be due in part, to the challenge of reaching and engaging parents in interventions. The current study used a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach to engage parents in co-creating and pilot testing a childhood obesity prevention intervention. Because CBPR approaches to childhood obesity prevention are new, this study aims to detail the creation, including the formation of the Citizen Action Group (CAG), and implementation of a childhood obesity prevention intervention using CBPR methods.

Methods

A CBPR approach was used to recruit community members to partner with university researchers in the CAG (n=12) to create and implement the Play it Forward! childhood obesity intervention. The intervention creation and implementation took two years. During year 1 (2011–2012), the CAG carried out a community needs and resources assessment and designed a community-based and family-focused childhood obesity prevention intervention. During year 2 (2012–2013), the CAG implemented the intervention and conducted an evaluation. Families (n = 50; 25 experimental/25 control group) with children ages 6–12 years participated in Play it Forward!

Results

Feasibility and process evaluation data suggested that the intervention was highly feasible and participants in both the CAG and intervention were highly satisfied. Specifically, over half of the families attended 75% of the Play it Forward! events and 33% of families attended all the events.

Conclusion

Equal collaboration between parents and academic researchers to address childhood obesity may be a promising approach that merits further testing.

Keywords: Community-based Participatory Research, Childhood Obesity Prevention, Family

INTRODUCTION

While the prevalence of childhood obesity may have started to plateau (Bethell, Simpson, Stumbo, Carle, & Gombojav, 2010; NIH, 2007; Ogden, Carroll, Curtin, Lamb, & Flegal, 2010; Ogden, Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2014; Wilson, 2009) childhood obesity more than doubled over the last two decades and is considered one of the most serious health problems facing youth (Ogden, Carroll, et al., 2010; Ogden, Lamb, et al., 2010; Ogden et al., 2006; Ogden et al., 2014). Childhood weight status strongly tracks into adulthood and has been linked to increased risk for cardiovascular disease, Type II diabetes, cancer and poor mental health as an adult (Daniels, 2006; Gordon-Larsen, The, & Adair, 2009; Merten, 2010; Pi-Sunyer, 2002; Popkin, 2007; Stovitz et al., 2010). Additionally, obesity places a large burden on the U.S. healthcare system with an estimated total cost of $147 billion per year in medical spending attributable to obesity (Finkelstein, Trogdon, Cohen, & Dietz, 2009).

To date, the majority of obesity interventions targeted to youth have been carried out in schools, health care clinics, or specialty care clinics (Caballero et al., 2003; Showell et al., 2013; Stevens, 2010; Story et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2015) with a focus on youth individual-level behaviors or school-level nutrition policies and practices. Although schools and health care clinics are a reasonable context for intervening, results have shown low to moderate success with reducing body mass index (BMI) and obesity using these types of interventions (Davison & Birch, 2001; Ebbeling, Pawlak, & Ludwig, 2002; Livingstone, 2006; Rao, 2008). Expert panels, researchers and the NIH have called for family-level and community-based interventions in order to address the multi-level systems in which youth reside and by which they are primarily influenced (Expert Committee Recommendations on the Assessment, Prevention, and Treatment of Child and Adolescent Overweight and Obesity, 2007; Lindsay, Sussner, Kim, & Gortmaker, 2006; Rhee, De Lago, Arscott-Mills, Mehta, & Davis, 2005). Thus, there is a critical need to address childhood obesity in a new way that will engage parents/families more fully in the intervention. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) (Israel, Eng, Schulz, & Parker, 2005; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003) methods are one such way because they engage community members and researchers as partners in co-creating interventions that address problems that have been resistant to traditional models of research (i.e., top-down). The main aim of this paper is to detail the CBPR process involved in the creation and implementation of a childhood obesity prevention intervention. Process evaluation and feasibility results will also be reported.

Community-based Participatory Research

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is an action research approach that emphasizes collaborative partnerships between community members, community organizations, and academic researchers to generate knowledge and solve local problems in order to have high potential for sustainability (Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003; Peterson & Gubrium, 2011). Hierarchical differences that can arise between academic researchers and partipcipants are flattened through this partnership and everyone works together to co-create knowledge and effect change throughout all aspects of the research process (Israel et al., 2003; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003). Each person contributes unique strengths and knowledge to improve the health and well-being of community members (Israel et al., 2003).

Several key tenets permeate CBPR projects (Israel et al., 2003; Israel et al., 2005; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003). First, CBPR acknowledges the community as a unit of identity in which all partners have membership. Second, CBPR emphasizes democratic partnerships between all project members as collaborators through every stage of knowledge- and intervention-development. Third, CBPR requires a deep investment in change that carries with it an element of challenging the status quo, improving the lives of members in a community and attending to social inequalities. Fourth, CBPR builds on strengths and resources within the community in order to address local concerns and solve relevant problems. Fifth, CBPR uses a cyclical process in which a problem is identified, solutions are developed within the context of the community’s existing resources, interventions are implemented, outcomes are evaluated, and interventions are modified in accord with new information as necessary. Sixth, CBPR promotes project partners’ humility and flexibility to accommodate changes as necessary and fosters co-learning and capacity building. Seventh, CBPR involves a long-term process and commitment to sustainability (Berge, Mendenhall, & Doherty, 2009; Doherty & Mendenhall, 2006; Doherty, Mendenhall, & Berge, 2010).

CBPR methods have gained increased credibility in health care and public health since the early 1990s (Israel et al., 2003; Israel et al., 2005; Minkler, 2000; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003). CBPR methods utilized in childhood obesity prevention interventions to date have typically involved partnering with schools or delivering the interventions within a community setting (e.g., community centers, health care clinics) (Bleich, Segal, Wu, Wilson, & Wang, 2013; Chomitz et al., 2010; Coffield, Nihiser, Sherry, & Economos, 2015; Economos et al., 2013; Hillier-Brown et al., 2014), rather than focusing on partnering with parent’s directly as part of the CBPR process. We are aware of one study that has applied CBPR methods using parent-engaged methods to childhood obesity (Davison, Jurkowski, Li, Kranz, & Lawson, 2013). The CBPR approach was used with parents of children ages 2–5 years who were enrolled in Head Start. Parents were equal partners in the development, implementation and evaluation of a CBPR childhood obesity prevention study. Parents and researchers conducted a community needs assessment and developed the Communities for Healthy Living (CHL) intervention which included a health communication campaign, family nutrition counseling, and a six week parent and child educational program. Results indicated that children reduced their rate of obesity, and sedentary behaviors and increased their levels of physical activity, and healthful dietary intake from pre- to post-intervention. However, this study did not include a control group and was conducted with young children. The current study aimed to corroborate results found in Davison’s (2013) CBPR childhood obesity prevention study, while also expanding results by testing the CBPR approach with parents of children ages 6–12 years and with a control group.

Theoretical Model

In carrying out the current study, we used the Citizen Health Care Model (Berge, Mendenhall, & Doherty, 2009; Doherty & Mendenhall, 2006; Doherty, Mendenhall, & Berge, 2010), a CBPR approach, to guide the study design, hypotheses, and analysis. As outlined in Table 1, Citizen Health Care begins with the notion that all personal health problems can also be seen as public problems. For example, childhood obesity can be viewed in terms of its consequences for families and the surrounding community. In addition, Citizen Health Care moves interdisciplinary collaboration from treating one individual at a time to collaborating with families and communities to effect change on a larger scale. The model is a systematic way to access a resource that is largely untapped: the knowledge, lived-experience, wisdom, and energy of individuals and their families who face challenging health issues in their everyday lives. The notion of “citizen” refers to individuals and their families becoming activated along with their neighbors and others who face similar health challenges in order to make a difference for a community. Ordinary citizens become assets in health care as they work as co-producers of health for themselves and their communities. The approach is empowering and uses democratic, small group strategies, with a “Citizen Action Group” (CAG) to produce collective action. Table 2 outlines the main strategies for implementing the Citizen Health Care CBPR approach with community partners and the “first steps” that were taken in the Play it Forward! intervention.

Table 1.

Core Principles of the Citizen Health Care Model*

| Core Principle | Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. The greatest untapped resource for improving health care is the knowledge, wisdom, and energy of individuals, families, and communities who face challenging health issues in their everyday lives. | Instead of first looking to professional resources, we look to family and community resources. |

| 2. Families and communities are producers of health and health care, not just clients or consumers. | This empowers families and communities to co-create health interventions, understandings, and influence in partnership with professionals. |

| 3. Health professionals are citizens, not just providers. | In this work, health professionals develop public skills as citizen professionals so that they can work in community groups with flattened hierarchies. |

| 4. Citizens drive programs, rather than programs servicing citizens. | If you begin with an established program, you will not end up with an initiative that is “owned and operated” by citizens. But a citizen initiative might create or adopt a program as one of its activities. |

| 5. Local communities must retrieve their own historical, cultural, and religious traditions of health and healing. | Each initiative should reflect the local culture in which it is positioned in order for the initiative to be co-owned; no two initiatives will look exactly alike. |

| 6. Citizen health initiatives should have a bold vision while working pragmatically on focused, specific projects. | Think big, act practically, and let your light shine in order to sustain motivation. |

Table 2.

Action Strategies for Citizen Health Care

| Action Strategy | Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Get buy-in from key professional leaders & administrators; “stakeholders”. | These are the gatekeepers who must support the initiation of a project based on its potential to meet the goal(s) of the community. Key point to emphasize to stakeholders: you want to move interdisciplinary collaboration from treating one individual at a time to collaborating with families and communities to effect change on a larger scale. It is best to request little or no budget, beyond a small amount of staff time, in order to allow the project enough incubation time before being expected to justify its outcomes. Play it Forward!: University researchers talked with several City Mayors and Parks and Recreation Directors to discuss the Citizen Health Care approach to collaboration and to identify potential “pressure points”. The Mayor and Parks and Recreation Director of Burnsville were very supportive of the pressure point and the Citizen Health Care CBPR model. This component of the CBPR process included several meetings (about two per City) with four different Mayors of Cities in the Twin Cities, MN. Ultimately Burnsville was the best fit for the project. |

| 2. Identify a health issue that is of great concern to both professionals and members of a specific community (e.g., clinic, neighborhood, cultural group in a geographical location). | Citizen Health Care begins with the notion that all personal health problems can also be seen as public problems. The health issue must be one that a community of citizens actually cares about—not just something we think they should care about. Additionally, professionals must care about the issue and have enough passion for it to sustain their efforts over time. It must be a “pressure point”. For example, childhood obesity is a pressure point because it can be viewed in terms of its consequences for individuals, families and the surrounding community. Play it Forward!: The “pressure point” of childhood obesity prevention was an issue that all stakeholders were passionate about. The pressure point was reframed as child health and wellness. This component of the CBPR process took four meetings to clearly define the pressure point. Pilot study ideas were also discussed from the beginning of the partnership. |

| 3. Identify potential community leaders who have personal experience with the health issue & who have relationships with the professional team. | Leaders should be ordinary members of the community who in some way have mastered the selected health issue in their own lives & have a desire to give back to their community. “Positional” leaders who head community agencies are generally not the best group to engage at this stage—they bring institutional priorities & constraints. Play it Forward!: After several meetings (4 meetings) with the Mayor, Parks and Recreation Director and university researchers, there was consensus to move forward with the pressure point. The Mayor, Parks and Recreation director and university researchers created criteria for characteristics of parents who would be a good fit for the Citizen Action Group (CAG). This component of the CBPR process took three meetings. |

| 4. Invite a small group of community leaders (three or four people) to meet several times with the professional team to explore the issue & see if there is a consensus to proceed with a larger community project. | These preliminary discussions help determine whether a Citizen Health Care project is feasible & begin creating a professional/citizen leadership group. Ultimately you want to access a community resource that is largely untapped: the knowledge, lived-experience, wisdom, and energy of individuals and their families who face challenging health issues in their everyday lives. Play it Forward!: The Mayor, Parks and Recreation director and university researchers created criteria for the CAG and recruitment of CAG members (3 meetings). Ultimately, the Mayor allowed her Parks and Recreation director to officially represent the City of Burnsville and she stepped out of the official CAG process. However, the Mayor did attend several Play it Forward! events to reinforce her involvement in the project. Flat hierarchies were employed from the beginning of the CBPR process, but the concept of a flat hierarchy was discussed at length at this key turning point when the CAG was about to be recruited. |

| 5. Strategize how to invite a larger group of community leaders (10–15) to begin the process of generating the project. | You must have a larger group invested in the process to facilitate a larger “We” focus. Ordinary “citizens” become assets in health care as they work alongside their neighbors and others as co-producers of health for themselves and their communities. Play it Forward!: The Mayor and Parks and Recreation Director of Burnsville had an email list of families who had attended city parks and recreation activities and events. These potential families fit the criteria the researchers and leadership at Burnsville City had collaboratively created. All families on the email list were invited to a launch event to see if they would be interested in becoming CAG members. This component took one month to carry out. About 15 parents attended the launch event. Ultimately, 9 parents were invited to participate in the CAG. These community parents were representative of the overall Paha Sapa neighborhood. There was a mix of male and female parents of children ages 6–12 years. |

| 6. Over the next six months have biweekly meetings using community organizing principles. | The following key steps are crucial, but can be slow & messy: (a) explore the community & citizen dimensions of the issue; (b) create a name & mission statement for the initiative; (c) conduct one-on-one interviews with a range of stakeholders; (d) generate potential action initiatives & process them in regards to the Citizen Health Care model & existing community resources; (e) decide on a specific action initiative & implement it. Play it Forward!: CAG members met bi-weekly to carry out a needs assessment. Each CAG member approached 5–10 neighbors who lived in the Paha Sapa neighborhood and who had children between the ages of 6–12 years. Based on their interview findings, a name and mission statement was created and potential action initiatives were created. CAG members used interview themes to create the intervention. |

| 7. Employ Citizen Health Care processes throughout the project. | The following steps will keep the initiative focused, strong, & increase sustainability: (a) democratic planning & decision making at every step; (b) mutual teaching & learning among community members; (c) creating ways to fold new learnings back into the community; (d) identifying & developing leaders; (e) using professional expertise selectively—“on tap,” not “on top”; (f) forging a sense of larger purpose. Play it Forward!: University researchers and Paha Sapa community members collaborated throughout every step of the needs assessment, intervention development, intervention delivery and pilot study data collection, analyses and presentation of results. |

Study Aims

Given the high prevalence of childhood and adolescent obesity and the need to try new approaches for addressing childhood obesity, the current study aimed to: (1) create and implement a family-focused childhood obesity prevention intervention using the Citizen Health Care model of CBPR by partnering with community members via a Citizen Action Group (CAG); and (2) examine the effectiveness of the intervention on child and family weight and weight-related behaviors (e.g., physical activity, sedentary behavior, dietary intake). This paper details aim one of the study. Specifically, the formation of the CAG, conducting a community needs and resources assessment, creation of the Play it Forward! intervention, implementation of the intervention, and feasibility and process evaluation of the intervention are reported here.

METHODS

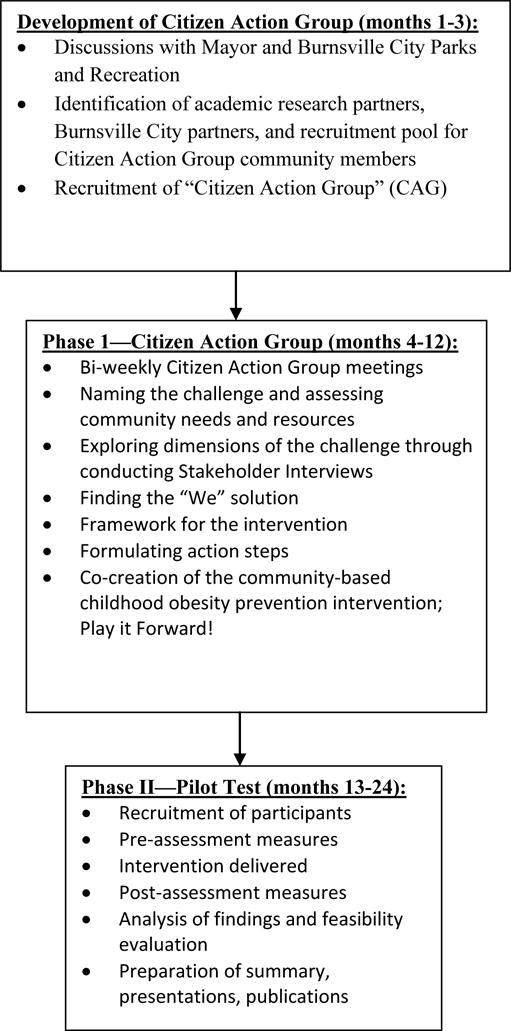

Figure 1 shows the developmental steps of the Play it Forward! childhood obesity prevention intervention. A CBPR approach was used from the inception of the study through analysis and dissemination of results. The Play it Forward! intervention was developed and implemented over a two year period between August 2011–2013 using the Citizen Health Care CBPR principles outlined in Table 1. Specific steps taken are detailed below and in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Diagram of Key Study Components

Development of the Citizen Action Group (CAG)

First steps in developing the CAG included talking to several interested communities regarding a “pressure point”, or an issue a community has passion/energy about changing, related to child health. Several meetings were held in different communities within the greater twin cities area of Minnesota to gauge interest in implementing a CBPR project. These meetings included discussions with key stakeholders (e.g., Mayor, Parks and Recreation Director) to get buy-in about using CBPR methods and to identify the pressure point to be targeted in the intervention (i.e., childhood obesity/child health). These meetings led to the identification of a neighborhood, Paha Sapa, Burnsville as the community to target for recruiting CAG members and for carrying out the intervention. The Paha Sapa neighborhood was intentionally selected because it is a dense neighborhood with many potential families for recruitment and because many families in this area had participated in the Burnsville City Parks and Recreation programs in the past. This increased the likelihood of recruiting parents and families who would be eligible for the CAG and the future intervention study (i.e., children ages 6–12 years old).

Recruitment of CAG members

Emails were sent to families who lived in the Paha Sapa neighborhood from the Burnsville City Parks and Recreation Department to invite interested parents to attend an initial launch event where a description of the Citizen Health Care CBPR process was described and the topic of child health and wellness was introduced as the pressure point to address in the community. This meeting was a type of “town hall” where: (1) information was presented about child health and the need for individual communities to take the lead in increasing options and resources for child health and (2) community members voiced their opinions about how they could be directly involved. At the end of the night, interested parents signed up to participate in the CAG.

CAG community members were representative of the surrounding Paha Sapa neighborhood where the intervention was carried out. Specifically, there were twelve members, with nine members representing the community and three representing university researchers. Of the nine community members, three were fathers, six mothers and the members were well distributed across age (range = 35–50yrs.) and race/ethnicity (White, Black, Hispanic). CAG members were intentionally not paid to co-partner in the CBPR process. This decision was made by the CAG as a way of creating sustainability of the project.

Community needs and resources assessment

Over the next eight months, an in-depth formative assessment of the Paha Sapa community was conducted by the newly formed CAG (n=12 members) via one-to-one interviews with neighbors and other community members (n=20) in Paha Sapa to identify challenges and resources for healthful eating and physical activity and to inform intervention development (see Table 3 for interview questions). Community members interviewed were representative of the surrounding Paha Sapa neighborhood and members were well distributed by sex, developmental age and stage (adolescents, mothers, fathers, single adults, grandparents) and race/ethnicity (White, Black, Hispanic). A qualitative analysis of themes was conducted by the CAG utilizing protocols used in our previous studies, which follow content analysis guidelines/protocols (Mendenhall, Berge, Harper, GreenCrow, LittleWalker, WhiteEagle, & BrownOwl, 2010). Overwhelmingly, community members interviewed identified the following themes from the community needs assessment: (1) desire for more physical activity opportunities in the neighborhood; (2) interest in physical activity events that were informal and even spontaneous, rather than “having one more thing to commit to in the family’s schedule”; (3) desire for events that incorporate healthy messages while simultaneously engaging in physical activity (e.g., “if playing with your child is important, have events with activities that promote parents and kids playing together”; “if eating healthy is important, have water and apple slices to eat as a way to rejuvenate after playing hard”); (4) desire for events that promote fun and enjoyment rather than competition and skill; (5) interest in physical activity events that encourage intergenerational play (i.e., older neighbors play with younger children, adolescents play with younger children); and (6) desire for physical activity events that could create community/neighborhood connectivity. CAG members used these themes as criteria that guided the creation of the intervention.

Table 3.

One-to-One Interview Questions Round One

| Interview Introduction: | I am part of a group in the community called Play it Forward! This is a parent initiative in the Paha Sapa neighborhood in partnership with the University of Minnesota. We are focusing on promoting healthy eating and physical activity in our children. As I’m sure you know, there is a big national conversation right now on children eating better and being more physically active. We are talking with a number of people in the neighborhood and community to learn about their thoughts, feelings, experiences, and ideas about this issue. Would you be willing to meet and talk with me for about 30–45 minutes? |

| Interview Questions: | |

| #1 | Could you first tell me about the ages of your children? |

| #2 | Do you see healthy eating and physical activity as a problem for our children? [If yes] What are some examples? |

| #3 | Why do you think the health of our children has become such a challenge? |

| #4 | How is it a struggle for you and your children? What have you tried—what’s working, not working? |

| #5 | [If a parent or grandparent] Do you struggle with the issues of healthy eating and activity yourself, or with your own children’s [grandchildren’s] children? |

| #6 | We want to raise awareness about this problem and develop ways that neighborhoods like ours can make a difference for children and families. What ideas do you have for us? What do you think we can do about this as a neighborhood? |

| #7 | Here are some action ideas we are considering: A Neighborhood Garden (give details) Playing together as families and neighborhoods; Buying Food in Bulk as a Neighborhood; A “Healthy Mothers, Healthy Kids Campaign” to counteract mother guilt over taking time to be active. I’m interested in your feedback about any of these ideas, plus other ideas that come to you? [Describe each idea in detail]. |

| #8 | Might you be interested in working with us some time in the future as we develop action steps in our neighborhood? |

| #9 | What are some talents, resources or skills you may have to offer related to any of the ideas I mentioned? |

| #10 | Is there anything else on your mind about what we have talked about? |

Several resources were also identified through this needs/resources assessment such as, (1) community members with expertise in specific types of physical activity (e.g., Tai Chi, cyclists, kickball/dodgeball, geocaching experts); (2) owners of small businesses that would support and advertise the Play it Forward! initiative; (3) resources for communicating about Play it Forward! events (websites, listservs, social media experts) and (4) other community members who would be interested in participating in Play it Forward!

Development of the Intervention: Play it Forward!

The CAG created a name that represented the purpose of the intervention: “Play it Forward!”. Specifically, CAG members wanted to instill within their community that being active was something that the community should believe in and pass on to the next generation while at the same time, ultimately reducing childhood obesity. In addition, being active as a community would simultaneously increase community connectedness. Next, the CAG created a mission statement: “Connecting Families and Neighbors through Healthy Play”. At CAG bi-weekly meetings (90 minutes each), a structured process was used where small group and large group processes were utilized to develop the intervention based on the community needs and resources assessment. After deciding on three main types of events that could be used to focus the neighborhood intervention on physical activity (i.e., large whole Paha Sapa events, break-out events and organic/small group events), the CAG went back to community members to conduct another round of one-to-one interviews to see if the physical activity intervention they had been developing would be of interest to the community (see Table 4 for interview questions). After another round of informative feedback from the community, the CAG decided on the final defining elements of the Play it Forward! intervention, including: (1) bi-weekly informal/organic physical activity events held at local parks that promoted cross-generational play; (2) the informal and often spontaneous/organic play will be led by local community members with skills/talents/interests in the specific physical activity/play promoted at each event; and (3) there will be simultaneous promotion of physical activity and healthy eating messages that allow for engaging in physical activity and healthy eating activities during Play it Forward! events.

Table 4.

One-to-One Interview Questions Round Two

| Introduction: | I am part of a group in the community called Play it Forward. This initiative focuses on promoting physical activity and healthy eating in our community and passing it on to future generations. We are talking with a number of people in the community to get their feedback about our initial ideas. Would you be willing to meet and talk with me for about 30 minutes? |

| Interview Questions: | |

| #1 | We are considering doing three types of community events. First, large events that everyone would be invited to. Second, break-out events that people would come to depending on their interest in the topic(s). Third, informal/organic events that naturally occur, but are posted on Facebook or some electronic format to let people know they are occurring. Let me tell you about each type of event separate and you can give me feedback as we go along. |

| #2 | First, the Whole Paha Sapa events would be planned and sponsored events for all neighbors in the Paha Sapa area. We would do things like: Dance parties, Amazing Race event, field games (e.g. playing soccer, kickball, volleyball), a Scavenger hunt-like event, Buckhill Run, or Obstacle Course. • I’m interested in your feedback about any of these ideas, plus other ideas that come to you? • When would be the best time to come to an event like this (e.g. Saturday, Sunday)? • How often do you think someone would want to attend an event like this? • Would you be interested in helping organize one of these events? |

| #3 | Second, the break-out events would be based on common interests of neighbors and would be held in public or private locations. We would do things like: Yoga, Talking circles/Peace-making, Pass it on recipes (cooking class), Artist in the Park (poetry slam, guitar, singing, etc), Book club, Park cleanup/service project, Group project like a chalk mural or massive kite flying (collectivity), Service Project, Photo voice project, Organized games with friendly competition, Bring a friend events, A “get to know your neighbor’ game, Talent/skill driven (e.g. Kite flying, juggling), Activity & Healthy food potluck with conversation around it (e.g. progressive dinner) • I’m interested in your feedback about any of these ideas, plus other ideas that come to you? • When would be the best time to come to an event like this (e.g. Saturday, Sunday)? • How often do you think someone would want to attend an event like this? • Would you be interested in helping organize one of these events? |

| #4 | Third, the informal/organic events would be spontaneous activities people would do and let others know about through social media (e.g. facebook, twitter, text messages). We would do things like: Pick-up-sports, Jump rope/Hop Scotch competition, Games that 3 or more can play (e.g. Frisbee, Basketball), Random sports day (e.g. Everyone brings random equipment to share), Water games (summer—water fight, balloon volleyball), Treasure hunts, Bike parade, Tai Chi/movement groups, Spontaneous “dance today,” Night games (e.g. Steal the Flag, Kick the Can, Ghost in the Graveyard), Explore Nature (e.g. Fishing, Biking, Hiking), Neighborhood food co-op, Community gardens, Cook-off. • I’m interested in your feedback about any of these ideas, plus other ideas that come to you? • When would be the best time to come to an event like this (e.g. Saturday, Sunday)? • How often do you think someone would want to attend an event like this? • Would you be interested in helping organize one of these events? |

| #5 | What ideas do you have for us? What are your overall thoughts or concerns about what we are trying to do? |

| #6 | Might you be interested in working with us some time in the future as we develop action steps in our neighborhood? [Ask about specific involvement if someone expressed interest in a particular idea.] |

| #7 | What are some talents, resources or skills you may have to offer related to any of the ideas I mentioned? |

| #8 | Anything else on your mind about what we have talked about? |

Implementing the Intervention

After the creation of the Play it Forward! intervention by the CAG, study recruitment began for pilot testing the intervention for feasibility and initial effectiveness. The overall study design was quasi-experimental, with an intervention (n=24 families) and control (n=26 families) group. For the experimental group, recruitment took place at a local elementary school. Flyers were sent home with children ages 6–12 in their backpacks indicating that a family event would be held where they could “play” together as a family and sign up to be a part of a study. Eligible families (i.e., have a child between the ages 6–12 and speak English) were recruited and then participated in a home visit to carry out pre- and post-measurements. These families became the Play it Forward! intervention group and participated in bi-weekly (i.e., twice a month) Play it Forward! events for six months (total=12 events; see Table 5). Staying true to the findings from the community interviews and the criteria created by the CAG for the intervention, experimental group families were told to come to as many events as they could in order to free parents from feeling tied down or committed to another activity/program in their busy family lives. Local parks and school playgrounds/fields within the Paha Sapa neighborhood were used to carry out the events. Large a-frame (i.e., sandwich boards) signs were created that were put up at every event that said, “Fun in Progress, Come Play”. These signs were used to remind families in the Paha Sapa neighborhood of the Play it Forward! events and attract any families walking by the event to join in the fun.

Table 5.

Play it Forward! Intervention Events

| Play it Forward! Event | Length of Event | Description of Event and Time Frame | Communication Modalities Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kite Flying in the Paha Sapa Park | 2 hrs. | Families and neighbors participated in a kite flying event where they first made a kite and then raced (i.e., which could go highest and fastest when running with the kite) their kites in a field at the Paha Sapa park. Participants could also bring their own kites to race. | Facebook, Shutterfly, email, Burnsville City Website |

| Spring Fever Dance at Paha Sapa Park | 2 ½ hrs. | Families and neighbors participated in a dance at the Paha Sapa park warming house. Specific dance activities included: hoola hoop contest, limbo stick, musical chairs and freestyle dance contest. Apple slices and water were provided as a healthy snack. | Facebook, Shutterfly, email, Burnsville City Website |

| Cinco de Mayo Fiesta and Fun! | 2 ½ hrs. | Families and neighbors participated in a field day with relay races, obstacle courses, tug-of-war, 100-yard dash, freeze tag at the Paha Sapa park. Baked chips and Salsa were provided as the snack with lime water. | Facebook, Shutterfly, email, Burnsville City Website |

| Tai Chi in the park | 1 ½ hrs. | Families and neighbors participated in Tai Chi in the Paha Sapa park taught by a local community member. | Facebook, Shutterfly, email, Burnsville City Website |

| Dodgeball, Kickball, Softball, Oh MY! | 2 hrs. | Families and neighbors participated in one or several pick-up games including dodgeball, kickball and softball at the Paha Sapa Park. | Facebook, Shutterfly, email, Burnsville City Website |

| Summer Bonfire and Night Games | 2 ½ hrs. | Families and neighbors participated in night games such as ghost in the graveyard, sharks and minnows, kick-the-can, flashlight tag and capture the flag at the Paha Sapa park. There was also a bonfire with roasted apple slices provided as a healthy snack. | Facebook, Shutterfly, email, blog, Burnsville City Website |

| Summer Bike Parade to Crystal Lake | 2 hrs. | Families and neighbors participated in decorating and parading their bikes, or walking, from Paha Sapa park to Crystal Lake park (approximately 1 mile). | Facebook, Shutterfly, email, blog, Twitter, Burnsville City Website, Craig’s List |

| Water fun at Crystal Lake Park | 2 ½ hrs. | Families and neighbors played water games such as water balloon volleyball, water relay races, sand castle sculpting and water fights at the Crystal Lake park. Summer melons such as watermelons, cantaloupes and honeydews were provided as a healthy snack. | Facebook, Shutterfly, email, blog, Twitter, Burnsville City Website, Craig’s List |

| Pick Up Games at Paha Sapa Park | 2 hrs. | Families and neighbors played basketball, dodge ball, kickball, flag football, softball, soccer at the Paha Sapa park. | Facebook, Shutterfly, email, blog, Twitter, Burnsville City Website, Craig’s List |

| Geocaching! | 2 hrs. | Families and neighbors participated in a geocaching adventure which had them make stops at historical sites within 2 miles of the Paha Sapa park. | Facebook, Shutterfly, email, blog, Twitter, Burnsville City Website, Craig’s List |

| Low Stress Back to School Play | 2 hrs. | Families and neighbors participated in school games such as four-square, hopscotch, jump rope/double dutch, and kickball. A healthy snack of air popped popcorn and lemon water was provided. | Facebook, Shutterfly, email, blog, Twitter, Burnsville City Website, Craig’s List |

| Fall Ahead Fun! Scavenger | 2 ½ hrs. | Families and neighbors participated in a scavenger hunt which required walking between three parks and picking up different types of garbage that they crossed off their scavenger hunt list. | Facebook, Shutterfly, email, blog, Twitter, Burnsville City Website, Craig’s List |

The control group was recruited from a bordering community in order to ensure that the two communities were comparable and to reduce potential contamination effects on study participants. Control families had the same eligibility criteria and participated in a home visit where pre- and post-measures were conducted. Control group families participated in “usual” community events or activities, such as school quarterly events (e.g., carnivals, silent auctions), over the same year period as the experimental group.

While the study design was not a true randomized controlled trial, the quasi-experimental design allowed for baseline and follow-up comparisons between the intervention and control groups in order to identify initial feasibility and effectiveness of the intervention. For study feasibility, the percent of experimental families attending Play it Forward! events was collected and process evaluation measures, including surveys and participant interviews were conducted. All study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Participants

Parent-child dyads (n=50) participated in the Play it Forward! study (see Table 6). Parents in the experimental group were between the ages of 34 to 46 (mean = 40.8; SD = 6.09) and parents in the control group were between the ages of 32–43 (mean = 37.2; SD = 5.34) (see Table 6). Children were between the ages of 6–12 years. Children in the 6–8 years age group were on average 7 years old (SD = 0.83) in both the experimental and control groups. Children in the 9–12 years age group were on average 10 years old (SD = 1.11) in both the experimental and control groups. Over sixty percent of participants were white, with about 20% being African (i.e., Somali) or African American. The majority of participants (75%) were from low-middle to middle class households.

Table 6.

Baseline socio-demographic characteristics of children and parents

| Experiment Group (families n=24) |

Control Group (families n=26) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Child age 6–8 (total n=22) | Experimental Group (child 6–8 yrs. n=8) | Control Group (child 6–8 yrs. n=14) |

|

| ||

| Age (Mean(SD)) | 7.13 (0.83) | 7.07 (0.83) |

|

| ||

| Gender (N(%)) | ||

| Female | 4 (50.0) | 6 (42.9) |

| Male | 4 (50.0) | 8 (57.1) |

|

| ||

| Child age 9–12 (total n=28) | Experimental Group (child 9–12 yrs. n=16) | Control Group (child 9–12 yrs. n=12) |

|

| ||

| Age (Mean (SD)) | 10.19 (1.11) | 10.17 (1.11) |

|

| ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | 8 (50.0) | 6 (50.0) |

| Male | 8 (50.0) | 6 (50.0) |

|

| ||

| Parent (total n=50) | Experimental Group (parent n=24) | Control Group (parent n=26) |

|

| ||

| Age | 40.76 (6.09) | 37.19 (5.34) |

|

| ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | 22 (91.7) | 25 (96.2) |

| Male | 2 (8.3) | 1 (3.8) |

|

| ||

| Ethnicity/Race (N(%)) | ||

| White | 16 (66.7) | 18 (69.2) |

| Black/AA | 5 (20.8) | 5 (19.3) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 3 (12.5) | 1 (3.8) |

| American Indian | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.7) |

|

| ||

| # of Child (N(%)) | ||

| 1 | 6 (25.0) | 2 (7.7) |

| 2 | 5 (20.8) | 11 (42.3) |

| 3 | 8 (33.3) | 6 (23.1) |

| 4 | 3 (12.5) | 6 (23.1) |

| 5 | 1 (4.2) | 1 (3.8) |

| 10 | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| ||

| Education (N(%)) | ||

| < High School | 1 (4.2) | 1 (3.8) |

| High School | 4 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| In College | 4 (16.7) | 9 (34.6) |

| College | 12 (50.0) | 16 (61.6) |

| over College | 3 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| ||

| Income (N(%)) | ||

| − $20,000 | 2 (8.3) | 1 (3.8) |

| $20,000 – $34,999 | 4 (16.7) | 1 (3.8) |

| $35,000 – $49,999 | 6 (25.0) | 6 (23.1) |

| $50,000 – $74,999 | 4 (16.7) | 7 (26.9) |

| $75,000 – $99,999 | 6 (25.0) | 8 (30.8) |

| $100,000 + | 2 (8.3) | 3 (11.5) |

Building in Sustainability

As part of the CAG’s CBPR process, sustainability was intentionally planned from the inception of the project. For example, discussions were had early on in the process regarding how to continue to grow leaders so that the project would continue, even if key CAG members moved or had to become less involved due to life circumstances (e.g., new job, sick family member) or if university researchers became less involved in the process. Additionally, during the design of the intervention by the CAG, sustainability was included as a criteria for choosing certain intervention components. For example, utilizing spontaneous mechanisms or low-maintenance physical activity events (e.g., kick the can, pick-up ball) was preferred versus depending on laborious pre-planned events to encourage physical activity. In addition, the tag line of “participate as you can” increased the likelihood that community members coming to the Play it Forward! events would continue to attend.

RESULTS

Feasibility results

Feasibility results from the current study indicated that using community-based participatory research (CBPR) methods was feasible in carrying out the childhood obesity prevention study. Over half of the families in the experimental group attended 75% of the events and 33% attended all the events. Additionally, using local parks and elementary schools was highly feasible. Because CAG members included Burnsville City staff and school district staff, there was no difficulty in having access to these community resources to carry out events. Furthermore, using social media to advertise Play it Forward! events was highly feasible. Specifically, 68% of families preferred the use of Shutterfly or Facebook reminders to receive event details, while 22% preferred email reminders, and 10% preferred phone calls. CAG members also identified that carrying out the Play it Forward! events was “low burden” because the events were either low-key pre-planned events (e.g., kick ball, dodge ball) or spontaneous (e.g., pick-up games; see Table 5).

Process evaluation results

Process evaluations were conducted with both CAG participants and study participants. CAG participants (i.e., community members and university researchers) reported “high satisfaction” (n=12/12; 100%) with the CAG formation process, the creation of the Play it Forward! intervention and the implementation of the intervention. Researchers noted feeling “supported by the community” and community members noted feeling “equal in decision making powers and in carrying out the study”. The majority of families in the Play it Forward! experimental group were highly satisfied (n= 20/24; 83%) with the intervention and noted that the intervention message of “participate as you can” made it more likely that they would participate in the intervention events.

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

The current study introduced a novel approach for family-based childhood obesity prevention. Using a CBPR framework, researchers and community members (parents primarily) collaboratively created an intervention within a 1-year period and carried out the intervention over a 1-year period. Results indicated high feasibility and satisfaction with the Paha Sapa intiative. These results corroborate Davison et. al.’s (2013) previous results showing high attendance rates and parent satisfaction with the parent-engaged CBPR approach and resulting Head Start program. This study used CBPR methodologies, suggesting that engaging the community as partners in the creation of childhood obesity prevention interventions may be a promising approach for childhood obesity prevention interventions. Thus, equal collaboration between parents and academic researchers to address childhood obesity merits further testing.

Also of note, this study allowed for flexibility in participation of the intervention by parents and children. Previous research has suggested that it is important for participants to attend as many intervention events as possible to receive the highest “dose” of the intervention. Results from the current study showed that allowing parents to come to as many events as they “reasonably could,” resulted in high feasibility and satisfaction by participants. Thus, it could be the case that giving participants a larger role in the designing of the intervention and in deciding their own level of involvement may allow for increased likelihood of intervention effectiveness.

CONCLUSION

Results from the current study showed high feasibility and participant satisfaction with the Play it Forward! childhood obesity prevention CBPR intervention. Equal collaboration between parents and academic researchers to address childhood obesity may be a promising approach that merits further testing. Further testing of CBPR methods for childhood obesity prevention interventions would be an important next step to corroborate the findings from this pilot feasibility study.

Acknowledgments

The Paha Sapa: Paly it Forward study was funded by UCare Minnesota and the CTSI (Clinical and Translational Science Institute) at the University of Minnesota.

References

- Berge JM, Mendenhall TJ, Doherty WJ. Using Community-based Participatory Research (CBPR) To Target Health Disparities in Families. Fam Relat. 2009;58(4):475–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2009.00567.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethell C, Simpson L, Stumbo S, Carle AC, Gombojav N. National, State and Local Disparities in Childhood Obesity. Health Affairs. 2010;29(3):347–356. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleich SN, Segal J, Wu Y, Wilson R, Wang Y. Systematic review of community-based childhood obesity prevention studies. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):e201–210. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero B, Clay T, Davis SM, Ethelbah B, Rock BH, Lohman T, Stevens J. Pathways: a school-based, randomized controlled trial for the prevention of obesity in American Indian schoolchildren. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(5):1030–1038. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.5.1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomitz VR, McGowan RJ, Wendel JM, Williams SA, Cabral HJ, King SE, Hacker KA. Healthy Living Cambridge Kids: a community-based participatory effort to promote healthy weight and fitness. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18(Suppl 1):S45–53. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffield E, Nihiser AJ, Sherry B, Economos CD. Shape Up Somerville: change in parent body mass indexes during a child-targeted, community-based environmental change intervention. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):e83–89. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2014.302361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels SR. The consequences of childhood overweight and obesity. Future Child. 2006;16(1):47–67. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison KK, Birch LL. Childhood overweight: A contextual model and recommendations for future research. Obesity Reviews. 2001;2:159–171. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00036.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison KK, Jurkowski JM, Li K, Kranz S, Lawson HA. A childhood obesity intervention developed by families for families: results from a pilot study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:3. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty WJ, Mendenhall TJ. Citizen health care: A model for engaging patients, families, and communities as co-producers of health. Families, Systems & Health. 2006;24:251–263. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty WJ, Mendenhall TJ, Berge JM. The Families and Democracy and Citizen Health Care Project. J Marital Fam Ther. 2010;36(4):389–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebbeling CB, Pawlak DB, Ludwig DS. Childhood obesity: Public-health crisis, common sense cure. Lancet. 2002;360:473–482. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09678-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economos CD, Hyatt RR, Must A, Goldberg JP, Kuder J, Naumova EN, Nelson ME. Shape Up Somerville two-year results: a community-based environmental change intervention sustains weight reduction in children. Prev Med. 2013;57(4):322–327. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Expert Committee Recommendations on the Assessment, Prevention, and Treatment of Child Adolescent Overweight and Obesity. Retrieved August. 2007;27:2007. from http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/433/ped_obesity_recs.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health Affairs. 2009;28(5):w822–831. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w822. doi: hlthaff.28.5.w822 [pii] 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Larsen P, The NS, Adair LS. Longitudinal trends in obesity in the United States from adolescence to the third decade of life. Obesity. 2009 doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillier-Brown FC, Bambra CL, Cairns JM, Kasim A, Moore HJ, Summerbell CD. A systematic review of the effectiveness of individual, community and societal level interventions at reducing socioeconomic inequalities in obesity amongst children. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:834. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B, Schultz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, Allen AJ, Guzman JR. Critical issues in developing and following community based participatory reserach principals. In: I. M. M. N. W., editor. Community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003. pp. 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay AC, Sussner KM, Kim J, Gortmaker S. The role of parents in preventing childhood obesity. Future Child. 2006;16(1):169–186. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone MB, McCaffrey TA, Rennie KL. Childhood obesity prevention studies: Lessons learned and to be learned. Public Health Nutrition. 2006;9(8A):1121–1129. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007668505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merten MJ. Weight status continuity and change from adolescence to young adulthood: Examining disease and health risk conditions. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18(7):1423–1428. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.365. doi: oby2009365 [pii] 10.1038/oby.2009.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M. Using participatory action research to build healthy communities. Public Health Reports. 2000;115:191–197. doi: 10.1093/phr/115.2.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Comminity-based participatory research for heatlh. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- N. I. f. H. C. M. (NIHCM), editor. NIH. Reducing health disparities among children: Strategies and programs for health plans. Washington DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden C, Carroll M, Curtin L, Lamb M, Flegal K. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303(3):8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden C, Lamb M, Carroll M, Flegal K. Obesity and Socioeconomic status in children and adolescents: United Stated, 2005–2008. NCHS Data Brief. 2010:51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295(13):1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JC, Gubrium A. Old wine in new bottles? The positioning of participation in 17 NIH-funded CBPR projects. Health Commun. 2011;26(8):724–734. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.566828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi-Sunyer FX. The obesity epidemic: Pathophysiology and consequences of obesity. Obesity Research. 2002;10(Suppl 2):97S–104S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popkin BM. Understanding global nutrition dynamics as a step towards controlling cancer incidence. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:61–67. doi: 10.1038/nrc2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao G. Childhood Obesity: Highlights of AMA Expert Committee Recommendations. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(1):56–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee KE, De Lago CW, Arscott-Mills T, Mehta SD, Davis RK. Factors associated with parental readiness to make changes for overweight children. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):e94–101. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Showell NN, Fawole O, Segal J, Wilson RF, Cheskin LJ, Bleich SN, Wang Y. A systematic review of home-based childhood obesity prevention studies. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):e193–200. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens CJ. Obesity prevention interventions for middle school-age children of ethnic minority: a review of the literature. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2010;15(3):233–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2010.00242.x. doi: JSPN242 [pii] 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2010.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Story M, Sherwood NE, Himes JH, Davis M, Jacobs DR, Jr, Cartwright Y, Rochon J. An after-school obesity prevention program for African-American girls: The Minnesota GEMS pilot study. Ethnicity & Disease. 2003;13(1 Suppl 1):S54–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stovitz S, Hannan P, Lytle L, Demerath E, Pereira M, Himes J. Child height and the risk of young-adult obesity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;38(1):74–77. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Cai L, Wu Y, Wilson RF, Weston C, Fawole O, Segal J. What childhood obesity prevention programmes work? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16(7):547–565. doi: 10.1111/obr.12277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DK. New perspectives on health disparities and obesity interventions in youth. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34(3):231–244. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]