Abstract

Purpose

Digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) is emerging as the new standard of care for breast cancer screening based on improved cancer detection coupled with reductions in recall compared to screening with digital mammography (DM) alone. However, many prior studies lack follow-up data to assess false negatives examinations. The purpose of this study is to assess if DBT is associated with improved screening outcomes based on follow-up data from tumor registries or pathology.

Methods

Retrospective analysis of prospective cohort data from three research centers performing DBT screening in the PROSPR consortium from 2011–2014 was performed. Recall and biopsy rates were assessed from 198,881 women age 40–74 years undergoing screening (142,883 DM and 55,998 DBT examinations). Cancer, cancer detection, and false negative rates and positive predictive values were assessed on examinations with one year of follow-up. Logistic regression was used to compare DBT to DM adjusting for research center, age, prior breast imaging, and breast density.

Results

There was a reduction in recall with DBT compared to DM (8.7% vs. 10.4%, p<0.0001), with adjusted OR=0.68 (95% CI=0.65–0.71). DBT demonstrated a statistically significant increase in cancer detection over DM (5.9 vs. 4.4/1,000 screened, adjusted OR=1.45, 95% CI=1.12–1.88), an improvement in PPV1 (6.4% for DBT vs. 4.1% for DM, adjusted OR=2.02, 95% CI=1.54–2.65), and no significant difference in false negative rates for DBT compared to DM (0.46 vs. 0.60/1,000 screened, p=0.347).

Conclusions

Our data support implementation of DBT screening based on increased cancer detection, reduced recall, and no difference in false negative screening examinations.

Keywords: Breast Cancer Screening, Mammography, Digital Breast Tomosynthesis

Introduction

Digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) is rapidly emerging as the new standard of care for breast cancer screening. This novel x-ray technique images the breast with multiple low-dose exposures obtained along an arc which are reconstructed into a series of thin images or “slices” of the breast [1,2]. The ability to scroll through the multiple reconstructed images minimizes the impact of overlapping structure which limits two-dimensional mammographic imaging [3]. The three-dimensional format of the DBT images allows better localization of lesions and improves the conspicuity of both benign and malignant lesions.

Thus far, early studies comparing screening with DBT combined with digital mammography (DM) to screening with DM alone have shown reductions in recall from 15% to 37% [4–11] and increases in cancer detection from 10%–35% [4–10]. These results have prompted the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to introduce billing codes adding a global reimbursement of approximately $56 [12] for DBT imaging further promoting the adoption of this new technology. While these prior studies are encouraging, the majority have not included necessary patient level follow-up to assess for false negatives or interval cancer rates. Additionally, there may have been differential use of the modalities so benefit may need to be adjusted to groups that are statistically comparable.

We present results comparing screening outcomes using DBT screening to DM alone from three research centers participating in the Population-Based Research Optimizing Screening through Personalized Regimens (PROSPR) consortium. The consortium includes large academic centers as well as community clinics reflecting a population-based evaluation of the possible benefit of DBT. We evaluated patient level data and conducted an analysis among a subset of patients with at least one year of follow-up to assess cancer rates, cancer detection rates, false negative rates, sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value.

METHODS

Study setting

This study was conducted as part of the NCI-funded PROSPR consortium. The overall aim of PROSPR is to conduct multi-site, coordinated, transdisciplinary research to evaluate and improve cancer screening processes. The ten PROSPR Research Centers reflect the diversity of US delivery system organizations. Our study included three PROSPR Research Centers evaluating breast cancer screening – University of Pennsylvania, an integrated health care delivery system; University of Vermont, a statewide breast cancer surveillance system; and Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth in conjunction with Brigham and Women’s Hospital, a primary care clinical network. A conceptual model of the breast cancer screening process with further details about the PROSPR research centers has been published previously [13]. All activities were approved by the institutional review boards at each research center and by the PROSPR Statistical Coordinating Center.

Data collection

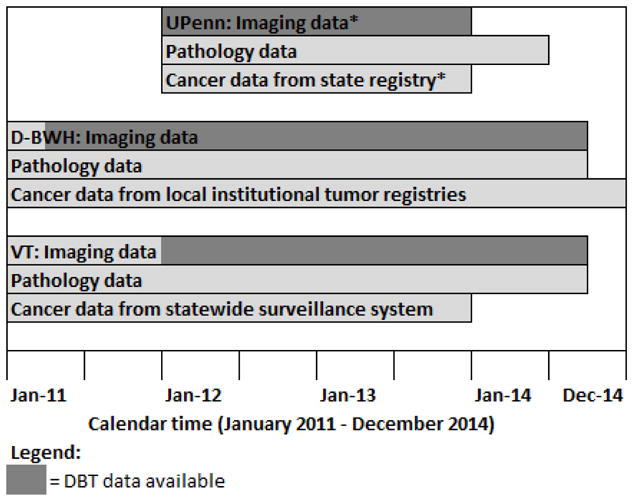

We pooled data from PROSPR’s central data repository to evaluate breast cancer screening outcomes with DBT in combination with DM (for brevity, henceforth called DBT) compared to DM alone. The overall study time frame was from 2011 to 2014; data availability varied by time for each research center (Figure 1). University of Pennsylvania (UPenn) began DBT screening for all patients on October 1, 2011 at a single imaging facility. A low volume DM facility with the same readers during the same time period was used for comparison. DBT screening began in January 2012 at one University of Vermont (VT) facility based on room availability and patient preference. Additional units were added in July 2012, November 2013, and December 2013. The Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health System in New Hampshire and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Massachusetts (D-BWH) began DBT screening in March 2011 at one facility. There was a more gradual conversion to DBT at other facilities during 2012 and 2013. DBT was used if requested by a patient or provider, and at some facilities women with dense breasts, baseline exams or with no obtainable prior imaging were targeted for DBT screening. We ascertained biopsy information from electronic health records and pathology databases. Cancer data came from local institutional tumor registries, state registries, and one statewide surveillance system. Pathology and cancer data availability varied by time for each center (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Data availability for imaging, pathology, and cancer outcome by calendar time.

Abbreviations: DBT=digital breast tomosynthesis, UPenn=University of Pennsylvania, D-BWH =Dartmouth-Hitchcock health system and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, VT=University of Vermont

*UPenn imaging data includes imaging from 1/1/12 to 12/31/13. Follow-up imaging data were available through 6/30/14. The largest imaging site began exclusively using tomosynthesis on October 1, 2011, but data availablility began on January 1, 2012. Cancer data also included UPenn institutional cancer registry data through June 2014.

Our analyses included all bilateral exams with an indication of screening and no other breast imaging within 3 months prior, among women 40–74 years of age with no known history of prior breast cancer. Furthermore, we limited exams to those with radiologists who had interpreted at least 50 DBT and 50 DM screening exams (UPenn=6, D-BWH=27, VT=14). A total of 55,998 DBT exams and 142,883 DM exams from 103,401 women met these criteria (45,049 women contributed 1 exam; 29,041 women contributed two exams; and 29,311 women contributed ≥3 exams). We defined a first exam as the first screening exam with no prior films and no prior imaging records available in PROSPR data, and no self-report of prior breast imaging. All other exams were considered subsequent exams. Breast density was extracted from the clinical screening report and used the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) categories (almost entirely fat, scattered fibroglandular densities, heterogeneously dense, extremely dense) [14]. Race and ethnicity data were available from electronic health records and patient self-report.

Outcome measures

We evaluated the following screening outcomes: recall rate (%), biopsy rate (%), cancer rate (per 1,000 exams), cancer detection rate (per 1,000 exams), false negative rate (per 1,000 exams), positive predictive value (%), sensitivity (%), and specificity (%). A positive screening exam included exams with BI-RADS assessment category 0, 3, 4, or 5. Recall rates are for positive screening exams; biopsy rates include any biopsy occurring after screening, regardless of the BI-RADS assessment category of the exam. Cancer rate was the number of cancers within 365 days of the screening exam; cancer detection rate was restricted to cancers within 365 days of a positive screen. False negative rates were determined from the difference between cancer rates and cancer detection rates. We evaluated the positive predictive value (PPV1), defined as the number of cancers diagnosed per number of positive screens. We calculated cancer rates, cancer detection rates, false negative rates, positive predictive values, sensitivity, and specificity among women under observation for at least one year (n=25,268 DBT and n=113,061 DM exams).

Statistical analysis

We compared screening outcomes (recall rates, biopsy rates, cancer rates, cancer detection rates, false negative rates, positive predictive values, sensitivity, and specificity) among DBT and DM exams using logistic regression and calculating odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For 2×2 tables we used two-sided Fisher exact tests; p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. A priori we adjusted the logistic regression models for research center, age (40–49, 50–59, 60–74 years), breast density (the four BI-RADS density categories), and first exam. In supplementary analyses, we further adjusted for race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, multiple races/other race). To evaluate the impact of differences in recall rate among interpreters, we additionally adjusted for interpreter in a conditional logistic regression model comparing recall rates. For the primary outcomes, we also considered a GEE logistic model that accounts for potential correlation of examinations within the same individual. These models gave the same OR estimate and confidence interval. Results given are from the standard logistic model since inference based on likelihood ratio testing is valid and did not differ from those from the GEE models. We used SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.) for all analyses.

RESULTS

DBT exams comprised 28% of all screening exams with the percentage varying according to how quickly the sites adopted DBT (Table 1). Compared to DM exams, DBT exams were more likely in women 40–49 years of age, among non-Hispanic black women, and among women with heterogeneously or extremely dense breasts. DBT exams were slightly more likely to be first screening exams compared to DM exams. Some of the differing characteristics between DM and DBT exams were due to differences in the populations being screened with DBT at each center, but remained important even after this adjustment.

Table 1.

Characteristics of exams using digital mammography (DM) alone or in combination with digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT)

| Characteristics | Digital mammography (DM) exams* (N = 142,883) | Tomosynthesis in combination with digital mammography (DBT) exams* (N = 55,998) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Age categories | ||||

| 40–49 | 37155 | 26.0 | 18668 | 33.3 |

| 50–59 | 51096 | 35.8 | 20839 | 36.4 |

| 60–74 | 54632 | 38.2 | 16941 | 30.3 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 116766 | 83.5 | 39697 | 72.3 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 9062 | 6.5 | 10987 | 20.0 |

| Hispanic | 9588 | 6.9 | 1572 | 2.9 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2966 | 2.1 | 1455 | 2.6 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 170 | 0.1 | 50 | 0.1 |

| Multiple races/other race | 1255 | 0.9 | 1164 | 2.1 |

| Unknown | 3076 | 1073 | ||

| Breast density | ||||

| Almost entirely fatty (1) | 21201 | 16.3 | 5905 | 11.2 |

| Scattered fibroglandular densities (2) | 64902 | 49.8 | 25588 | 48.6 |

| Heterogeneously dense (3) | 38445 | 29.5 | 18412 | 35.0 |

| Extremely dense (4) | 5858 | 4.5 | 2721 | 5.2 |

| Unknown | 12447 | 3372 | ||

| Prior screening | ||||

| First screening exam | 11254 | 7.9 | 6471 | 11.6 |

| Subsequent screening exam | 131629 | 92.1 | 49527 | 88.4 |

| PROSPR research center | ||||

| UPenn | 2981 | 2.1 | 20240 | 36.1 |

| D-BWH | 74911 | 52.4 | 16775 | 30.0 |

| VT | 64991 | 45.5 | 18983 | 33.9 |

Abbreviations: UPenn=University of Pennsylvania, D-BWH=Dartmouth-Hitchcock health system and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, VT=University of Vermont

Restricted to exams read by interpreters with at least 50 DM screens and 50 DBT screens (UPenn=6, Dartmouth-BWH=27, VT=14).

The overall recall rate for DBT and DM screening exams was 8.7% and 10.4%, respectively (Table 2, p<0.0001). The odds of recall was 32% lower for DBT compared to DM after adjusting for center, age, breast density, and first exam (OR=0.68, 95% CI=0.65–0.71). Stratification by individual interpreters did not change the adjusted OR substantially (OR=0.72, 95% CI=0.69–0.75). Biopsy rates were statistically significantly higher for DBT compared to DM (2.0% DBT vs. 1.8% DM, p=0.0074). However, after adjusting for center, age, breast density, and first exam the odds of biopsy were statistically significantly lower for DBT than DM (OR=0.85, 95% CI=0.77–0.93).

Table 2.

Recall rates and biopsy rates for digital breast tomosynthesis in combination with digital mammography (DBT) compared to digital mammography (DM) alone by PROSPR research center

| UPenn | D-BWH | VT | Overall | Unadjusted | Adjusted† | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DM n=2,981 |

DBT n=20,240 |

DM n=74,911 |

DBT n=16,775 |

DM n=64,991 |

DBT n=18,983 |

DM n=142,883 |

DBT n=55,998 |

|||||||||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | p-value | n | % | n | % | p-value | n | % | n | % | p-value | n | % | n | % | p-value | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Recall rate* | 299 | 10.0 | 1891 | 9.3 | 0.227 | 7000 | 9.3 | 1383 | 8.2 | <0.0001 | 7585 | 11.7 | 1582 | 8.3 | <0.0001 | 14884 | 10.4 | 4856 | 8.7 | <0.0001 | 0.82 | (0.79–0.85) | 0.68 | (0.65–0.71) |

| Biopsy rate | 71 | 2.4 | 586 | 2.9 | 0.124 | 1452 | 1.9 | 220 | 1.3 | <0.0001 | 1024 | 1.6 | 293 | 1.5 | 0.791 | 2547 | 1.8 | 1099 | 2.0 | 0.0074 | 1.10 | (1.03–1.19) | 0.85 | (0.77–0.93) |

Abbreviations: UPenn=University of Pennsylvania, D-BWH=Dartmouth-Hitchcock health system and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, VT=University of Vermont

Recall rate includes BIRADS 0, 3, 4, and 5 exams.

Adjusted for center, age (age 40–49, 50–59, 60–74), breast density (categories 1, 2, 3, 4), and first exam.

We observed an overall cancer rate of 6.5 per 1,000 DBT exams compared to 4.9 per 1,000 DM exams among exams with at least one year of follow-up (Table 3, p=0.0016, adjusted OR=1.49, 95% CI=1.17–1.89). The invasive cancer rate was also higher for DBT relative to DM (4.7 vs. 3.7 per 1,000 exams, p=0.0252; adjusted OR=1.45, 95% CI=1.09–1.92). The overall cancer detection rate was higher for DBT relative to DM (overall: 5.9 vs. 4.4 per 1,000 exams, p=0.0026; adjusted OR=1.45, 95% CI 1.12–1.88). Restricted to invasive disease only, the invasive cancer detection rate was also higher: 4.2 vs. 3.3 per 1,000 exams, p=0.045; adjusted OR=1.38, 95% CI=1.02–1.87). The PPV1 statistically significantly increased for DBT compared to DM (6.4% vs. 4.1%, p<0.0001, adjusted OR=2.02, 95% CI=1.54–2.65). The false negative rates were similar for both modalities with rates of 0.60 for DBT vs. 0.46 for DM per 1,000 screened (adjusted OR=0.55, 95% CI=0.13–2.26).

Table 3.

Cancer outcomes for digital breast tomosynthesis in combination with digital mammography (DBT) compared to digital mammography (DM) alone

| Cancer outcomes‡ | DM* n=113,061 |

DBT* n=25,268 |

p-value | Unadjusted | Adjusted† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | ||||

| Cancer rate per 1,000 | 4.9 | 6.5 | 0.0016 | 1.33 | (1.12–1.59) | 1.49 | (1.17–1.89) |

| Invasive cancer rate per 1,000 | 3.7 | 4.7 | 0.0252 | 1.27 | (1.04–1.56) | 1.45 | (1.09–1.92) |

| Total cancers (n) | 551 | 164 | |||||

| Invasive cancers (n) | 419 | 119 | |||||

| Ductal carcinoma in situ (n) | 132 | 45 | |||||

| Cancer detection rate per 1,000 | 4.4 | 5.9 | 0.0026 | 1.34 | (1.11–1.61) | 1.45 | (1.12–1.88) |

| Invasive cancer detection rate per 1,000 | 3.3 | 4.2 | 0.0449 | 1.26 | (1.01–1.56) | 1.38 | (1.02–1.87) |

| Total cancers (n) | 499 | 149 | |||||

| Invasive cancers (n) | 378 | 106 | |||||

| Ductal carcinoma in situ (n) | 121 | 43 | |||||

| False negative rate per 1,000 | 0.46 | 0.60 | 0.347 | 0.94 | (0.28–3.14) | 0.55 | (0.13–2.26) |

| PPV1 (cancers/recall), % | 4.1 | 6.4 | <0.0001 | 1.60 | (1.32–1.93) | 2.02 | (1.54–2.65) |

| Sensitivity % | 90.6 | 90.9 | 1.00 | 1.03 | (0.57–1.89) | 0.79 | (0.38–1.64) |

| Specificity % | 89.7 | 91.3 | <0.0001 | 1.22 | (1.16–1.28) | 1.39 | (1.30–1.48) |

Exams were restricted to women under observation for at least 1 year.

Adjusted for center, age (age 40–49, 50–59, 60–74), breast density (categories 1, 2, 3, 4), and first exam.

Lobular cancer in situ is not included. Invasive or in situ behavior was unknown for one cancer diagnosis.

Sensitivity was not improved (DBT=90.9%, DM=90.6%; adjusted OR=0.79, 95% CI=0.38–1.64); however, specificity did increase (DBT=91.3%, DM=89.7%; p<0.0001; adjusted OR=1.39, 95% CI=1.30–1.48). In supplementary analyses we further adjusted all multivariable models evaluating screening outcomes for race/ethnicity and the ORs did not meaningfully change (results not shown).

We evaluated all screening outcomes by age group (40–49 and 50–74 years) and breast density (non-dense versus dense). The adjusted ORs comparing DBT to DM for recall rate were similar for each age group and for each breast density group (Table 4). For biopsy rates, the adjusted ORs were comparable by age and by breast density, although there was some suggestion that the magnitude of the adjusted OR comparing DBT to DM was greater among dense than non-dense breasts. Sample sizes were small for cancer diagnoses. Nevertheless, there was a suggestion that the magnitude of the adjusted OR comparing DBT to DM for cancer rate, cancer detection rate, and PPV1 was greater among women ages 40–49 than ages 50–74, and greater among non-dense than dense breasts.

Table 4.

Screening outcomes for digital breast tomosynthesis in combination with digital mammography (DBT) compared to digital mammography (DM) alone by age and breast density

| DM | DBT | p-value | Unadjusted | Adjusted§ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | ||

| Recall rate* | |||||||||

| Age 40–49 | 5479 | 14.8 | 2124 | 11.4 | <0.0001 | 0.74 | (0.70–0.90) | 0.65 | (0.61–0.70) |

| Age 50–74 | 9405 | 8.9 | 2732 | 7.3 | <0.0001 | 0.81 | (0.77–0.85) | 0.71 | (0.67–0.74) |

| Nondense† | 7861 | 9.1 | 2328 | 7.4 | <0.0001 | 0.80 | (0.76–0.83) | 0.67 | (0.63–0.71) |

| Dense† | 5561 | 12.6 | 2186 | 10.3 | <0.0001 | 0.80 | (0.76–0.85) | 0.70 | (0.66–0.74) |

| Biopsy rate* | |||||||||

| Age 40–49 | 851 | 2.3 | 424 | 2.3 | 0.904 | 0.99 | (0.88–1.12) | 0.86 | (0.75–1.00) |

| Age 50–74 | 1696 | 1.6 | 675 | 1.8 | 0.0088 | 1.13 | (1.03–1.24) | 0.83 | (0.74–0.94) |

| Nondense† | 1221 | 1.4 | 598 | 1.9 | <0.0001 | 1.35 | (1.22–1.49) | 0.92 | (0.81–1.04) |

| Dense† | 979 | 2.2 | 458 | 2.2 | 0.754 | 0.98 | (0.88–1.10) | 0.79 | (0.69–0.90) |

| Cancer rate per 1,000‡ | |||||||||

| Age 40–49 | 104 | 3.4 | 47 | 5.6 | 0.0053 | 1.66 | (1.17–2.34) | 1.63 | (1.04–2.56)|| |

| Age 50–74 | 447 | 5.4 | 117 | 7.0 | 0.0210 | 1.28 | (1.04–1.57) | 1.35 | (1.02–1.79) |

| Nondense† | 299 | 4.5 | 87 | 5.6 | 0.0787 | 1.25 | (0.98–1.58) | 1.58 | (1.14–2.19) |

| Dense† | 193 | 5.5 | 73 | 7.8 | 0.0100 | 1.44 | (1.10–1.88) | 1.39 | (0.97–1.99) |

| Cancer detection rate per 1,000‡ | |||||||||

| Age 40–49 | 89 | 2.9 | 40 | 4.7 | 0.0130 | 1.65 | (1.13–2.39) | 1.53 | (0.93–2.50)|| |

| Age 50–74 | 410 | 5.0 | 109 | 6.5 | 0.0163 | 1.30 | (1.05–1.61) | 1.33 | (0.99–1.79) |

| Nondense† | 275 | 4.1 | 82 | 5.3 | 0.0580 | 1.28 | (1.00–1.63) | 1.55 | (1.11–2.18) |

| Dense† | 166 | 4.7 | 63 | 6.8 | 0.0117 | 1.44 | (1.08–1.93) | 1.31 | (0.88–1.95) |

| PPV1 (cancers/recall)‡, % | |||||||||

| Age 40–49 | 89 | 1.9 | 40 | 3.8 | 0.0005 | 2.02 | (1.38–2.95) | 1.96 | (1.18–3.26)|| |

| Age 50–74 | 410 | 5.5 | 109 | 8.6 | <0.0001 | 1.63 | (1.31–2.03) | 1.79 | (1.31–2.45) |

| Nondense† | 275 | 4.4 | 82 | 6.6 | 0.0013 | 1.54 | (1.19–1.98) | 2.32 | (1.62–3.34) |

| Dense† | 166 | 3.7 | 63 | 6.0 | 0.0010 | 1.69 | (1.25–2.27) | 1.70 | (1.13–2.56) |

Recall rate includes BIRADS 0, 3, 4, and 5 exams. Total number of exams for recall rate and biopsy rate: n=142,883 DM, n=55,998 DBT.

Nondense includes almost entirely fatty (1) and scattered fibroglandular densities (2). Dense includes heterogeneously dense (3) and extremely dense (4).

Cancer rates, cancer detection rates, and PPV1s were restricted to women under observation for at least 1 year. Total number of exams: n=113,061 DM, n=25,268 DBT.

Adjusted for center and first exam. ORs by age are additionally adjusted for breast density (categories 1, 2, 3, 4) when possible. ORs by breast density are additionally adjusted for age (age 40–49, 50–59, 60–74).

Adjusted only for center and first exam.

CONCLUSION

The results from our multi-center cohort study further support that screening with DBT increases cancer detection, reduces recalls, and does not increase false negative exams compared to screening with DM alone. In the subset of patients with at least one year follow-up, we observed a statistically significant improvement in specificity. Additionally, our findings support that the reduction in recall can be achieved with a statistically significant 34% increase in overall cancer detection or 1.5 more cancers detected per 1,000 screened with DBT screening compared to DM alone. In comparing invasive cancer detection rates, there was a 27% increase or 0.9 additional invasive cancers detected per 1,000 screened with DBT, not as large an increase as achieved in other large studies, but still statistically significant (7). We also compared the recall rate, cancer rate, and cancer detection rate among all exams by age group to Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium data based on 2,061,691 digital mammography exams from years 2004–2008 [15]. While the overall cancer rates were slightly higher in both our DM and DBT cohorts compared to the BCSC, the cancer detection rate was significantly higher in our DBT cohort (results not shown).

Our study is important because it is the first U.S. multi-site study to include a subset of the screened population with at least one year of imaging follow-up. While the number of patients with one year of follow-up is limited to 138,329 (70% of the examinations), and the study was not powered to evaluate false negative rates, we observed no statistically significant change in the false negative rates for DBT versus DM (0.60 versus 0.46 per 1,000 screened). In Skaane’s interval analysis of the first 12,621 subjects screened in a multi-arm, prospective trial with only 9 months of follow-up [4], there was a 40% increase in invasive cancers and 3 known interval cancers for a rate of 0.2 per 1,000 screened. In the STORM trial, a prospective, multi-armed reader study with a minimum of 13 months follow-up the interval cancer rate was 0.82/1000 screens for both the DM and DBT reading arms, but an absolute difference in cancer detection of 2.7 per 1,000 screened with DBT compared with DM alone [16]. In our two separate yet concurrent screening populations with follow-up, the false negative rates of 0.60 and 0.46/1,000 screened for DBT and DM respectively are lower, but must be viewed with caution since our definition of a false negative screen may have included cancers detected within one year by other screening modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound. The classic definition of an interval cancer is a cancer that presents symptomatically after a negative screening exam, and before the next scheduled screen [17]. However, in our recent publication of the single site UPenn data, the interval cancer rate using this classic definition was similar to the rate in this multi-site study [18]. Further analysis of our false negative cases is on-going to determine mode of presentation.

The overall relative reduction in recall rate of 15.6% or 13 women per 1,000 screened achieved in our population screened with DBT compared to those screened with DM alone is in keeping with other studies [4,6–11]. When adjusted for center as well as patient age and breast density, we showed a 32% decrease in the odds of recall with DBT versus DM alone (OR=0.68, 95% CI=0.65–0.71). Thus far, this is the only such patient data published from a multi-center site. This data further supports that the benefits of screening with DBT may be achievable across many different populations and sites and readers.

In our study, although the absolute recall reduction with DBT was greater for women with dense than for those with non-dense breasts (23 versus 17 per 1000 screened), both were statistically significant. However, when adjusted for center, first exam, and age, the odds of recall comparing DBT to DM were similar for women with dense and non-dense breasts. When stratifying by age, the recall reduction was greater for women ages 40–49 than for women ages 50–74 and the odds of recall were statistically significantly lower for DBT than for DM for both age groups even after adjusting for breast density. These findings demonstrate that all women may benefit from improved screening with DBT with no particular advantage due to age or breast density.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting our findings. Each of the research centers began DBT screening at different times with variable volumes and data captured within PROSPR and this was not always from the initiation of DBT screening. Therefore, the data represent samples from different points in the “learning curve” of implementing this new modality. We are investigating time trends in DBT performance, but that is beyond the scope of this paper. In addition, the populations at the various sites were quite different in terms of race/ethnicity and potential intrinsic individual risk level that may have contributed to variability in recall and cancer rates. There may also be some misclassification of first versus subsequent exams due to limited retrospective imaging data at some centers; however, we do not expect that this would meaningfully impact our results.

Despite these limitations, our multi-site study is the first to have follow-up data at the patient level with comprehensive cancer data sources, so that sensitivity and specificity calculations may be estimated for DBT screening. We have shown that across multiple, diverse research centers, screening with DBT is associated with a statistically significant increase in cancer detection with a concomitant improvement in specificity further supporting that this innovative technology offers critical improvements over breast cancer screening with DM alone.

Acknowledgments

Primary Funding Source: National Cancer Institute.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI)-funded Population-based Research Optimizing Screening through Personalized Regimens (PROSPR) consortium (grant numbers U01CA163304 to M.T., W.B.; U54CA163303 and P01 CA154292 to D.L.W., B.S., S.H.; U54CA163307 to A.N.A.T., T.O., J.H.; U54CA163313 to E.F.C., K.A., M.S.)

NOTES

The authors thank the participating PROSPR Research Centers for the data they have provided for this study. A list of the PROSPR investigators and contributing research staff are provided at: http://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/prospr/

Abbreviations

- BI-RADS

Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System

- CI

Confidence interval

- DBT

Digital breast tomosynthesis

- D-BWH

Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health System in New Hampshire and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Massachusetts

- DM

Digital mammography

- GEE

Generalized estimating equations

- NCI

National Cancer Institute

- OR

Odds ratio

- PPV1

Positive predictive value

- PROSPR

Population-Based Research Optimizing Screening through Personalized Regimens

- UPenn

University of Pennsylvania

- US

United States

- VT

University of Vermont

Footnotes

Author contributions: Dr Conant had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity

CONFLICTS of INTEREST:

Author E.F.C. is a consultant and has been a lecturer for Hologic, Inc., Bedford MA and Siemen’s Healthcare. Author S.P.P. has been renumerated for participating as a reader for Biomedical Systems, St. Louis, MO. Author S.D.H. holds stock in Hologic, Inc. Bedford, MA. Author K.A. is a consultant to GlaxoSmithKline, Philadelphia, PA.

References

- 1.Sechopoulos I. A review of breast tomosynthesis. Part I. The image acquisition process. Med Phys. 2013;40(1):014301. doi: 10.1118/1.4770279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sechopoulos I. A review of breast tomosynthesis. Part II. Image reconstruction, processing and analysis, and advanced applications. Med Phys. 2013;40(1):014302. doi: 10.1118/1.4770281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niklason LT, Christian BT, Niklason LE, et al. Digital tomosynthesis in breast imaging. Radiology. 1997;205(2):399–406. doi: 10.1148/radiology.205.2.9356620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skaane P, Bandos AI, Gullien R, et al. Comparison of digital mammography alone and digital mammography plus tomosynthesis in a population-based screening program. Radiology. 2013;267(1):47–56. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12121373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciatto S, Houssami N, Bernardi D, et al. Integration of 3D digital mammography with tomosynthesis for population breast-cancer screening (STORM): a prospective comparison study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(7):583–9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rose SL, Tidwell AL, Bujnoch LJ, et al. Implementation of breast tomosynthesis in a routine screening practice: an observational study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200(6):1401–8. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedewald SM, Rafferty EA, Rose SL, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis in combination with digital mammography. JAMA. 2014;311(24):2499–507. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.6095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCarthy AM, Kontos D, Synnestvedt M, et al. Screening outcomes following implementation of digital breast tomosynthesis in a general-population screening program. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(11) doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durand MA, Haas BM, Xiapan Y, et al. Early Clinical Experience with Digital Breast Tomosynthesis for Screening Mammography. Radiology. 2014:1313–19. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14131319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lourenco AP, Barry-Brooks M, Baird GL, Tuttle A, Mainiero MB. Changes in Recall Type and Patient Treatment Following Implementation of Screening Digital Breast Tomosynthesis. Radiology. 2014:1403–17. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14140317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haas BM, Kalr V, Geisel J, et al. Comparison of tomosynthesis plus digital mammography and digital mammography alone for breast cancer screening. Radiology. 2013;269(3):694–700. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. [accessed 9/30/2015]; http://www.acr.org/News-Publications/News/News-Articles/2014/Economics/20141105-CMS-Establishes-Values-for-Breast-Tomosynthesis-in-2015-Final-Rule.

- 13.Onego T, Beaber EF, Sprague BL, et al. Breast cancer screening in an era of personalized regimens: a conceptual model and National Cancer Institute initiative for risk-based and preference-based approaches at a population level. Cancer. 2014 Oct 1;120(19):2955–64. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Orsi CJ, Bassett LW, Berg WA, et al. BI-RADS: Mammography. In: D’Orsi CJ, Mendelson EB, Ikeda DM, et al., editors. Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System: ACR BI-RADS–Breast Imaging Atlas. 4. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15. [accessed 9/30/2015]; http://breastscreening.cancer.gov/statistics/benchmarks/screening/

- 16.Houssami N, Abraham LA, Kerlikowske K, et al. Risk Factors for Second Screen-Detected or Interval Breast Cancers in Women with a Personal History of Breast Cancer Participating in Mammography Screening Cancer. Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013 May;22:946–961. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1208-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Houssami N, Macaskill P, Bernardi D, et al. Breast screening using 2D-mammography or integrating digital breast tomosynthesis (3D-mammography) for single-reading or double-reading - Evidence to guide future screening strategies. Eur J Cancer. 2014 Jul;50(10):1799–807. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDonald ES, Oustimov A, Weinstein SP, Synnestvedt M, Schnall M, Conant EF. Effectiveness of digital breast tomosynthesis compared with digital mammography: Outcomes analysis from 3 years of breast cancer screening. JAMA Onc. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5536. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]