Abstract

Objective

This study was designed to compare the effectiveness of granisetron plus dexamethasone for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery.

Methods

We searched the literature in the Cochrane Library, PubMed, EMBASE, and CNKI.

Results

In total, 11 randomized controlled trials were enrolled in this analysis. The meta-analysis showed that granisetron in combination with dexamethasone was significantly more effective than granisetron alone in preventing PONV in patients undergoing laparoscopy surgery. No significant differences in adverse reactions (dizziness and headache) were found in association with dexamethasone.

Conclusion

Granisetron in combination with dexamethasone was significantly more effective than granisetron alone in preventing PONV in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery, with no difference in adverse reactions between the two groups. Granisetron alone or granisetron plus dexamethasone can be used to prevent PONV in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery.

Keywords: Granisetron, dexamethasone, laparoscopic surgery, postoperative nausea and vomiting, meta-analysis

Introduction

Laparoscopic surgery has been widely applied in clinical practice because it is associated with minimal trauma and rapid recovery. However, carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum, the need for general anaesthesia, and other factors lead to a high incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy (53%–72%).1 PONV may give rise to increased wound tension, high venous pressure, water and electrolyte disorders, acid–base imbalance, aspiration and asphyxia, and other complications.2 Therefore, it is an important risk factor for a prolonged length of hospitalization and poor postoperative recovery.

Granisetron, a serotonin (5-HT3) receptor antagonist, has been widely used in clinical trials. Studies have shown that granisetron is more effective in preventing PONV than traditional drugs. Dexamethasone is also effective in preventing PONV in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery. Additionally, the efficacy of granisetron in combination with dexamethasone is superior to that of granisetron alone. However, no meta-analysis of its effectiveness and safety has been conducted. This meta-analysis was therefore performed to determine the clinical efficacy of administering dexamethasone and granisetron before induction of anaesthesia in the prevention of PONV after laparoscopic surgery and to identify any interactions between the two drugs.

Materials and Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for this meta-analysis were as follows: (1) randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with or without blinding and with no language limitations; (2) patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery; (3) granisetron alone as the experimental group and granisetron plus dexamethasone as the control group; and (4) PONV and other adverse reactions (dizziness and headache) after 24 h as the measurement index.

The exclusion criteria were the absence of full text, data that could not be extracted, and duplicate publications.

Search strategy

All relevant published RCTs were identified by searching PubMed, the Cochrane Library, EMBASE, and CNKI. The major English index terms used in the search were laparoscopic surgery, nausea, vomiting, granisetron, and dexamethasone. We also employed Google Scholar and other search engines to identify relevant literature on the Internet.

Literature screening

Two reviewers independently screened the studies based on the inclusion criteria and then assessed the quality of each study. The reviewers then extracted data based on predesigned tables and cross-checked them with each other. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third party. Great efforts were made to contact the authors for supplementation of incomplete data.

Quality assessment

We evaluated the methodological quality of all enrolled studies using the Jadad scale. The results were controlled by two observers, and disagreements were resolved through discussion. The maximum total score was 5 points. A trial was given 1 point for being described as double-blind and 1 additional point for including a specific description of the method of double-blinding, 1 point for being described as randomized and 1 additional point for including a specific description of the randomization method, and 1 point for describing the reasons for patient withdrawal.

Statistical analysis

We adopted RevMan 5.2 (Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) to calculate the statistical heterogeneity and effect size and to conduct a meta-analysis on all studies with clinical homogeneity. Enumeration data were analysed using the relative risk (RR), continuous variables are expressed as the mean difference, and the effect size of both is represented by the 95% confidence interval (95% CI). We performed a subgroup analysis of potential heterogeneous factors and employed the chi-square test to assess the heterogeneity of each study. A fixed-effects model was used to perform the meta-analysis when no statistical heterogeneity was found (P > 0.1, I2 < 50%). When statistical heterogeneity was present (P < 0.1, I2 > 50 %), we analysed the sources of heterogeneity and conducted a subgroup analysis on heterogeneity factors. A random-effects model was employed if significant heterogeneity but no clinical heterogeneity was present between the two study groups. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis. When the heterogeneity between two groups was too large or the data source could not be found, we utilized a descriptive analysis.

Results

Search results

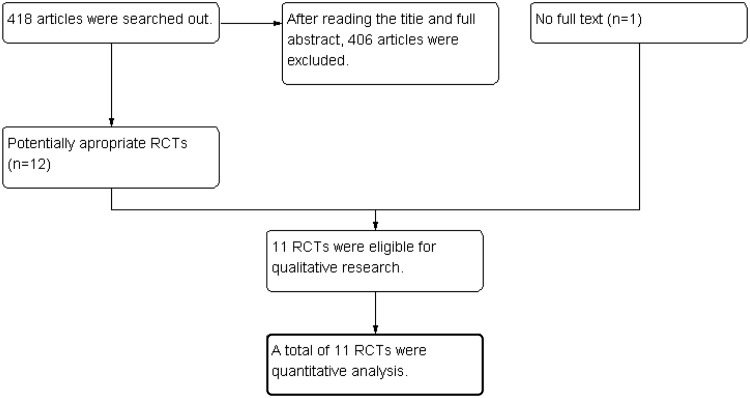

Initially, 418 studies were evaluated. A total of 406 studies, including RCTs, that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded after reading the titles, abstracts, and full texts. One study3 without a full text was excluded. Ultimately, 11 RCTs were included in the meta-analysis4–13 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the present meta-analysis.

Basic characteristics and quality assessment of included studies

The meta-analysis enrolled 11 studies, but the methodological quality was quite different among the studies. The basic characteristics and Jadad scale scores of the studies are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Author (published year) | N | Grouping | Surgical setting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fujii et al. 2003 | 100 | Granisetron | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

| Granisetron + dexamethasone | |||

| Moussa and Oregan 2007 | 120 | Granisetron | Laparoscopic bariatric surgery |

| Granisetron + dexamethasone | |||

| Granisetron + droperidol | |||

| Saline | |||

| Fujii et al. 2000 | 120 | Granisetron | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

| Granisetron + dexamethasone | |||

| Biswas and Rudra 2003 | 120 | Granisetron | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

| Granisetron + dexamethasone | |||

| Khan et al. 2006 | 160 | Granisetron | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

| Granisetron + dexamethasone | |||

| Saline | |||

| Bao and Wei 2013 | 120 | Granisetron | |

| Granisetron + dexamethasone | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | ||

| Saline | |||

| Chai et al. 2007 | 60 | Granisetron | Laparoscopic appendectomy |

| Granisetron + dexamethasone | |||

| Saline | |||

| Chen et al. 2006 | 120 | Granisetron | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

| Granisetron + dexamethasone | |||

| Saline | |||

| Kuang et al. 2005 | 90 | Granisetron | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

| Granisetron + dexamethasone | |||

| Saline | |||

| Xu et al. 2009 | 120 | Granisetron | Gynecologic laparoscopic surgery |

| Granisetron + dexamethasone | |||

| Saline | |||

| Dexamethasone | |||

| Zhao 2014 | 80 | Granisetron + dexamethasone | Gynecologic laparoscopic surgery |

| Saline |

Table 2.

Methodological quality of the trials included in the meta-analysis.

| Author (published year) | Jadad score | Blinding | Concealment allocation | Randomization method | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fujii et al. 2003 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Moussa and Oregan 2007 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Fujii et al. 2000 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Biswas and Rudra 2003 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Khan et al. 2006 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Bao et al. 2013 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Chai et al. 2007 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Chen et al. 2006 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Kuang et al. 2005 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Xu et al. 2009 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Zhao 2014 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Meta-analysis results

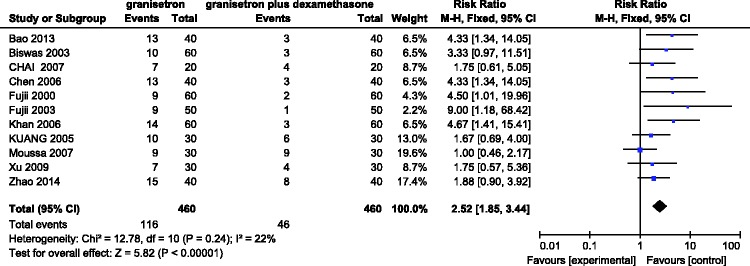

Incidence of PONV within first 24 h after administering granisetron alone versus granisetron plus dexamethasone

Eleven RCTs involving 920 patients evaluated the incidence of PONV with granisetron versus granisetron in combination with dexamethasone in the first 24 h after laparoscopic surgery. A fix-effects model was adopted when no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 22%) was found among the studies. The meta-analysis suggested a statistically significant difference in the incidence between the two groups (RR = 2.52, 95% CI = 1.85–3.44, P < 0.00001) in that the effectiveness of granisetron in combination with dexamethasone was better than that of granisetron alone (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting in the first 24 h after administering granisetron alone versus granisetron plus dexamethasone.

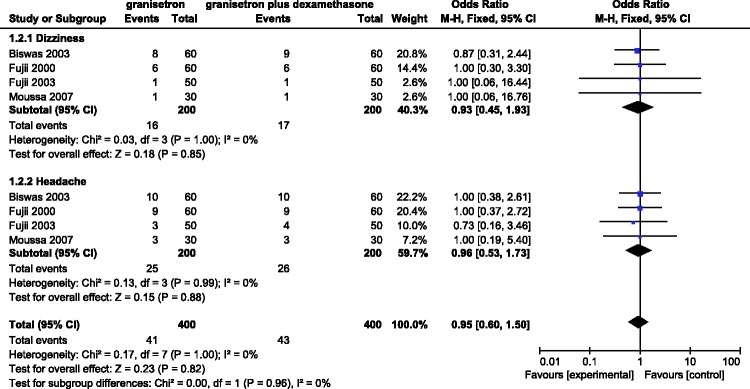

Incidence of adverse reactions (dizziness and headache) within first 24 h after administering granisetron alone versus granisetron plus dexamethasone

Four RCTs involving 400 patients evaluated the incidence of adverse reactions with granisetron versus granisetron plus dexamethasone in the first 24 h after laparoscopic surgery. A fixed-effects model was employed when significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) was found among the studies. The results showed that the time point at which adverse reactions occurred after laparoscopic surgery was not significantly different between the two groups (dizziness: RR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.45–1.93; headache: RR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.53–1.73). That is, there was no difference in postoperative adverse reactions between the two groups (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Incidence of adverse reactions (dizziness and headache) in the first 24 h after administering granisetron alone versus granisetron plus dexamethasone.

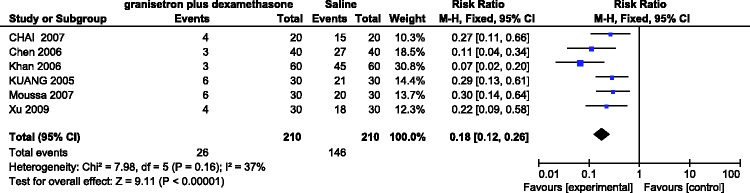

Incidence of PONV within first 24 h after after administering granisetron plus dexamethasone versus saline

Six RCTs involving 420 patients evaluated the incidence of PONV with granisetron plus dexamethasone versus saline in the first 24 h after laparoscopic surgery. No significant heterogeneity was found among the studies (I2 = 37%). A fixed-effects model showed a significant difference in the incidence of PONV between the two groups (RR = 0.18, 95% CI = 0.12–0.26, P < 0.00001) in that granisetron plus dexamethasone more effectively prevented the occurrence of PONV (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting in the first 24 h after administering granisetron plus dexamethasone versus saline.

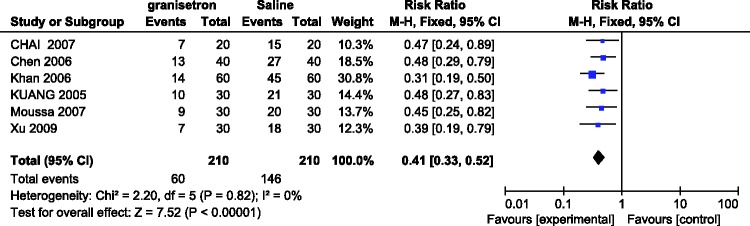

Incidence of PONV within first 24 h after administering granisetron versus saline

Six RCTs involving 420 patients evaluated the incidence of PONV with granisetron versus saline in the first 24 h after laparoscopic surgery. No significant heterogeneity was found among the studies (I2 = 0%). A fixed-effects model showed a significant difference in the incidence of PONV between the two groups (RR = 0.41, 95% CI = 0.33–0.52, P < 0.00001) in that granisetron more effectively prevented the occurrence of PONV (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting in the first 24 h after administering granisetron alone versus saline.

Publication bias

The funnel plot revealed no significant differences with respect to all outcomes.

Discussion

The meta-analysis suggests that granisetron plus dexamethasone is much more effective than granisetron alone in preventing PONV after laparoscopic surgery and that granisetron alone is as effective as dexamethasone alone in the prevention of PONV after laparoscopic surgery. Additionally, no difference was detected between granisetron plus dexamethasone and granisetron alone in the prevention of adverse reactions after laparoscopic surgery.

Despite the benefits of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in terms of minimal trauma, mild postoperative pain, and rapid recovery, the incidence of PONV is very high and seriously affects the patient’s recovery and rest. Granisetron is a highly selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonist. The mechanism by which granisetron controls PONV is to take the nerve endings of 5-HT3 receptor by antagonizing the central and peripheral chemosensory area fans, thus suppressing nausea and vomiting.

In recent years, dexamethasone has been universally recognized as an effective agent in chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and prevention of PONV. Dexamethasone has multiple effects on the central nervous system. The glucocorticoid receptor has been proven to exist among the anti-nausea and anti-emetic regions of the brain, and dexamethasone can adjusted to the level of a messenger, the concentration of the receptor, and signal transduction to play its role.14 Dexamethasone can also promote the release of endorphins. The peripheral antiemetic effect of dexamethasone may be related to inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis as well as reduction and promotion of the amount of 5-HT3. For example, 5-HT3 is secreted by pheochromocytomas in the gastrointestinal mucosa, and the anti-inflammatory effects of dexamethasone can inhibit gastrointestinal oedema, thereby reducing the synthesis and release of 5-HT3.15 The most frequently reported adverse effects of dexamethasone include an increased risk of infection, suppression of the adrenal gland, and delaying wound healing. Additionally, dexamethasone has a longer half-life than granisetron, and their combination thus enhances their antiemetic effects.

This meta-analysis demonstrated that the two sets of basic information (patient grouping and surgical setting) were comparable and balanced among the studies. However, some studies did not specifically describe their randomization, double-blinding, or follow-up methods. Moreover, because of the limited number of enrolled studies, the sample sizes for the subanalyses were small.

The results of this meta-analysis suggest that granisetron plus dexamethasone is more suitable than granisetron alone for preventing PONV after laparoscopic surgery. Additionally, no difference in adverse reactions after laparoscopic surgery was found between granisetron plus dexamethasone and granisetron alone. Either granisetron alone or granisetron plus dexamethasone can prevent PONV in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to You-Jing Luo, MD for her extensive support, which substantially improved the quality of the manuscript.

Declaration of conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Moussa AA, Oregan PJ. Prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing laparoscopic bariatric surgery–granisetron alone vs granisetron combined with dexamethasone/droperidol. Middle East J Anaesthesiol 2007; 19: 357–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsang YY, Poon CM, Lee KW, et al. Predictive factors of long hospital stay after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Asian J Surg 2007; 30: 23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MA, SM, NS, et al. Comparison of the efficacy of granisetron-dexamethasone versus ondansetron-dexamethasone in prevention of nausea and vomiting following gynecologic laparoscopic surgeries.[J]. Iranian Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility 2013(56).

- 4.Kuan Q, Guo LP, Yi F, Li YC. Granisetron and granisetron dexamethasone combination for prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. China Journal of Endoscopy 2005; 04: 424–431. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao HL. Granisetron dexamethasone combination for prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after women laparoscopic surgery. Contemporary Medicine 2014; 02: 78–79. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biswas BN, Rudra A. Comparison of granisetron and granisetron plus dexamethasone for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2003; 47: 79–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujii Y, Tanaka H, Kawasaki T. A randomized, double-blind comparison of granisetron alone and combined with dexamethasone for post-laparoscopic cholecystectomy emetic symptoms. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp 2003; 64: 514–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 8.Fujii Y, Saitoh Y, Tanaka H, et al. Granisetron/dexamethasone combination for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2000; 17: 64–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan MP, Kohli M, Kumar GA, et al. Granisetron and granisetron dexamethasone combination for prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a double blind, placebo controlled study. J Anaesth Clin Pharmacol 2006; 22: 261–265. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Q, Xu ZY, Shi BS, et al. Granisetron dexamethasone combination for prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Proceeding of Clinical Medicine 2006; 07: 493–494. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bao CP, Wei JS. Granisetron plus dexamethasone for prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Journal of Qiqihar Medical College 2013; 20: 2998–2999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chai J, Wu XY, Chen WM. Granisetron plus dexamethasone for prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic appendectomy surgery. Journal of Applied Clinical Pediatrics 2007; 11: 867–868. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu GY, Chen CF, Wu CB. Granisetron plus dexamethasone for prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after gynecologic laparoscopic surgery. Medical Innovation of China 2009; 27: 53–54. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu YH, Li MJ, Wang PC, et al. Use of dexamethasone on the prophylaxis of nausea and vomiting after tympanomastoid surgery. Laryngoscope 2001; 111: 1271–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henzi I, Walder B, Tramer MR. Dexamethasone for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: a quantitative systematic review. Anesth Analg 2000; 90: 186–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]