Abstract

Objective

To investigate the efficacy and safety outcomes of combination therapy used to optimize etanercept treatment in patients with psoriasis treated in real-life clinical practice.

Methods

Data from patients presenting with psoriasis, treated initially with etanercept monotherapy, were analysed retrospectively. Patients subsequently treated with combination therapy were further analysed. The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score was recorded for all patients receiving comedication; a subjective pain score was recorded in those with psoriatic arthritis receiving comedication after 12, 24 and 48 weeks’ treatment and thereafter at 6-month intervals.

Results

From the database of 400 patients treated with etanercept, 37 patients (18 male; 19 female; mean age 59.43 years) underwent combination therapy due to lack of efficacy. Patients received mostly short-term (range 4–34 weeks) comedication with corticosteroids, cyclosporine, methotrexate, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acitretin or sulphasalazine. There were significant reductions in the mean PASI score from baseline at all timepoints. There were also significant reductions in the mean pain VAS score from baseline at all timepoints in patients with psoriatic arthritis. The drug survival rate was 59.6% over a mean duration of 323 weeks of etanercept treatment. The safety profile of combination therapy was satisfactory.

Conclusions

Short-term comedication in combination with etanercept may optimize treatment options and improve long-term drug survival in patients with psoriasis.

Keywords: Comedication, etanercept, psoriasis, tumour necrosis factor-α antagonists

Introduction

Several therapeutic options are available for the treatment of psoriasis; however, traditional systemic therapies are often unable to meet desired treatment goals and their high-dose and/or long-term use is associated with organ toxicity.1–3 Over the past two decades, the introduction of biological agents has dramatically improved treatment outcomes, although they are not effective in all individuals with psoriasis.2 According to current guidelines,4 there is no approved indication for any combination of a biological agent with a conventional systemic treatment in psoriasis, although comedication has been shown to be a frequent dermatological practice in up to 30% of patients receiving a tumour necrosis factor-α antagonist.5–8 Combination treatment may provide improved therapeutic results for patients who inadequately respond to a single drug; moreover, combination therapy may reduce safety concerns and cumulative toxicity, as a lower dose of two single agents may offer a better safety and efficacy profile when used in combination.5–8 The present retrospective study aimed to describe experience of a combination treatment strategy used in real-life clinical practice to optimize etanercept efficacy and drug survival in patients with plaque-type psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis.

Patients and methods

A retrospective analysis was conducted on a clinical database at the Department of Dermatology, University of Rome Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy, of adult patients with plaque-type psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis, initially treated with etanercept monotherapy for a minimum of 6 months in the period between January 2004 and December 2008. Those treated with a combination treatment at baseline and/or a history of active infectious disorders (including active tuberculosis), or a history of serious chronic, recurrent, opportunistic infective diseases, demyelinating diseases or recent neoplasms, were excluded from the study. Pregnant or breastfeeding women were also excluded. Patients were originally eligible for etanercept treatment if they presented with moderate-to-severe psoriasis defined by a Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score9 ≥ 10 and an affected body surface area > 10%, were resistant and/or intolerant to at least two traditional systemic treatments and/or had contraindications to such therapies.4 Coexistence of a joint impairment was diagnosed according to the CASPAR (Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis) criteria.10

In patients with psoriatic arthritis, etanercept was administered as monotherapy at a starting dose of 50 mg subcutaneously once a week or 25 mg twice a week as a continuous regimen; patients with plaque-type psoriasis received 50 mg etanercept subcutaneously twice a week for the first 12 weeks, followed by 50 mg once a week or 25 mg twice a week. At each follow-up visit after 12, 24 and 48 weeks’ treatment and then at 6-month intervals throughout the treatment period, the PASI score was recorded in all patients and a subjective pain score using a visual analogue scale (VAS) from 0 to 100 was recorded in patients with psoriatic arthritis. If primary or secondary inefficacy occurred, comedication was considered.

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of good clinical practice. All patients gave written informed consent for study-related evaluations.

Statistical analyses

Results were presented as mean and range and were analysed using the Student’s t-test. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using

Statistics (Version W1.59, Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, UK).

Results

Data from 400 patients treated with etanercept were analysed, of whom 37 patients (9.25%) (18 male, 19 female) with a mean age of 59.43 years (range 42–83 years) received combination therapy during etanercept treatment due to inefficacy of etanercept alone. Of the comedicated patients, 22 out of 37 (59.46%) received concomitant methotrexate at a mean dose of 10 mg/week for a mean duration of 11.34 weeks (range 4–34 weeks), 11 (50%) for cutaneous inefficacy, nine (40.91%) for articular inefficacy and four (18.18%) for both cutaneous and articular inefficacy. Eight of 37 patients (21.62%) received concomitant cyclosporine (3.5 mg/kg daily) for a mean duration of 10.5 weeks (4–20 weeks), in all cases for cutaneous inefficacy; eight of 37 (21.62%) received concomitant nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug treatments (paracetamol, ibuprofen, naproxen or cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors, given as needed) for a mean duration of 9.75 weeks (range 4–16 weeks), all for articular inefficacy; four of 37 (10.81%) received concomitant corticosteroids (prednisone) at 25 mg/day for a mean duration of 7 weeks (range 4–10 weeks), one (25%) for cutaneous inefficacy, two (50%) for articular inefficacy and one (25%) for both cutaneous and articular inefficacy; four of 37 (10.81%) received concomitant sulphasalazine at a mean dose of 2 g daily for a mean duration of 13 weeks (range 8–16 weeks), in all cases for articular inefficacy; one of 37 (2.7%) was treated with acitretin (0.5 mg/kg daily) for 16 weeks for a skin flare up (Figure 1). During the observation period, 14 of the 37 patients were given more than one comedication at different timepoints: four received methotrexate and corticosteroids, four received methotrexate and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, two received methotrexate and cyclosporine, two received two different cycles of methotrexate, one received methotrexate and sulphasalazine, and one received sulphasalazine and a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Figure 1.

Percentage of patients with psoriasis (n = 37) receiving various comedications alongside etanercept treatment. MTX, methotrexate; CyA, cyclosporine; RTX, acitretin; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; CCS, corticosteroids; SSZ, sulphasalazine.

Psoriatic arthritis comorbidity was found in 33 of the 37 patients (89.19%). Cardiovascular comorbidities were frequent, being reported in 15 of 37 patients (40.54%), comprising hypertension in 12 patients, acute myocardial infarction in one patient and atrial fibrillation in one patient. Other comorbid conditions included a thyroid-related disorder in three patients, depression in two patients and single cases of anaemia, asthma, hepatitis B virus infection and emphysema.

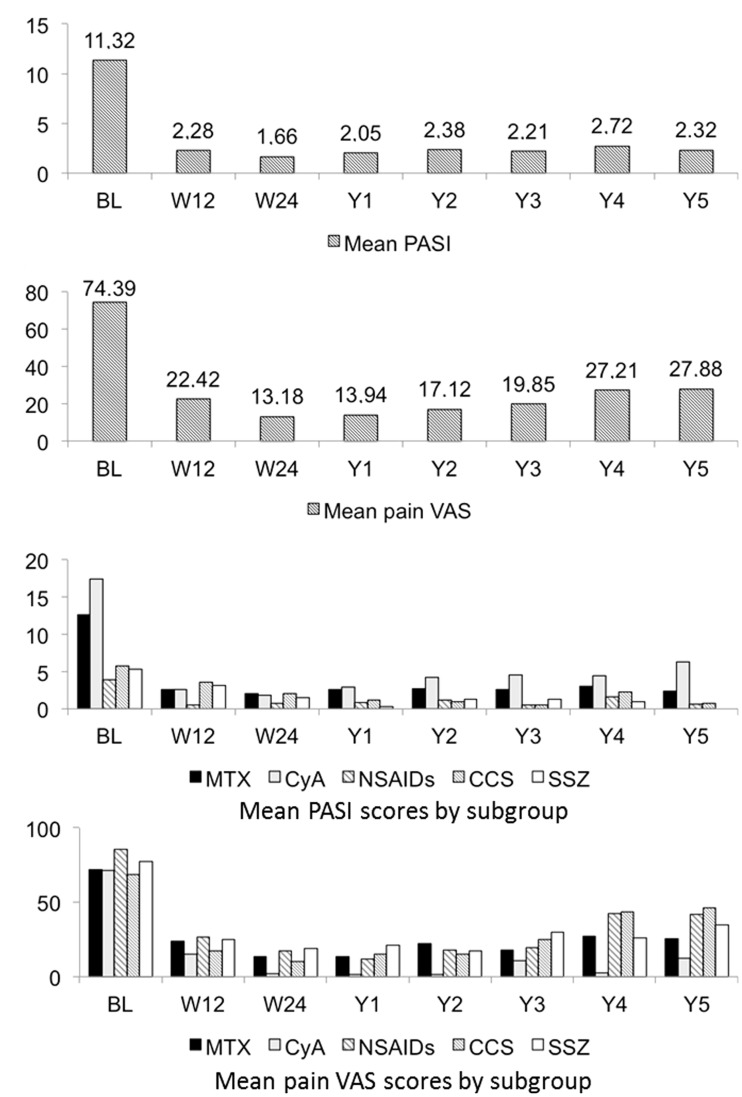

Mean PASI scores in all comedicated patients and mean pain VAS scores in comedicated patients with psoriatic arthritis over the study period are given in Figure 2. Overall values are shown in Figure 2A and 2B, and values according to comedication subgroups are shown in Figure 2C and 2D. Among the comedicated patients, psoriasis severity was characterized at baseline by a mean PASI score of 11.32 (range 0.8–52) (Figure 2A), with a mean pain VAS score in patients with psoriatic arthritis of 74.4 (range 30–100) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Mean Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scores9 in patients with psoriasis treated with etanercept and various comedications (n = 37). (B) Mean pain visual analogue scale (VAS) scores in patients with psoriatic arthritis treated with etanercept and various comedications (n = 33). (C) Mean PASI scores in patients with psoriasis treated with etanercept and various comedication (n = 37) according to comedication subgroup. (D) Mean pain VAS scores in patients with psoriatic arthritis treated with etanercept and various comedications (n = 33) according to comedication subgroup. MTX, methotrexate; CyA, cyclosporine; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; CCS, corticosteroids; SSZ, sulphasalazine; BL, baseline; W, week; Y, year.

The overall mean etanercept treatment duration in comedicated patients was 323.03 weeks (range 24–480 weeks). Clinical efficacy for skin manifestations was expressed by a mean PASI score reduction from 11.32 at baseline to 2.28 at week 12, 1.66 at week 24, 2.05 at year 1 and to 2.32 at year 5 (P < 0.0001 for all) (Figure 2A). The proportion of patients achieving a PASI score reduction of ≥ 75% from baseline was 64.86% at week 12, increasing to 67.57% at week 24, 72.97% at week 52 and reducing again to 62.52% at year 5.

In patients with psoriatic arthritis, consistent improvement was demonstrated by a reduction in the mean pain VAS score from 74.39 to 22.42 at week 12, 13.18 at week 24, 13.94 at year 1 and to 27.88 at year 5 (P < 0.001 for all) (Figure 2B).

Overall, 15 of the 37 patients (40.54%) receiving comedication withdrew from etanercept treatment and switched to other therapies because of adverse events (n = 3) or inefficacy (n = 12), giving a high drug survival rate for etanercept of 59.46% and a high mean treatment duration for those on comedication (323.03 weeks). In all 12 patients who stopped etanercept treatment due to inefficacy, the interruption occurred at the end of the comedication period (methotrexate in six patients, cyclosporine in three patients, corticosteroids in two patients and sulphasalazine in one patient).

The safety profile of combination therapy was satisfactory. Adverse events that did not lead to treatment interruption comprised injection site reactions in four patients, upper respiratory tract infections in two patients and worsening of emphysema in one patient before the comedication period, drug-related hypertension and gastrointestinal disorder in two patients during cyclosporine–etanercept combination therapy, and drug-related mucositis and malaise in one patient during methotrexate–etanercept combination therapy. In addition, there were two severe adverse events leading to treatment interruption: hyperplastic polyp of the rectum and thyroid carcinoma occurred in the post-comedication phase of etanercept treatment in two patients who had undergone methotrexate–etanercept and cyclosporine–etanercept combination therapy, respectively.

Discussion

The results of the present study show that combination therapy was effective in patients with reduced efficacy or loss of response during etanercept treatment, with statistically significant improvements being observed in both PASI scores (all patients) and pain VAS scores (only undertaken in those with psoriatic arthritis) at all post-baseline timepoints.

The long-term management of psoriasis with conventional systemic treatments may present some critical safety issues, while patients may experience primary or secondary inefficacy and, less commonly, adverse effects leading to treatment interruption during therapy with biological agents.11 The use of combination therapy may optimize treatment outcome. From the present analysis of a large clinical database comprising 400 patients treated with etanercept, 37 patients (9.25%), with a high prevalence of psoriatic arthritis (89.19%), received a combination of etanercept plus a conventional systemic agent. Combination therapy proved to have good safety and efficacy profiles, and was able to affect treatment rescue in cases of inefficacy, even with short-term treatment cycles. Overall, 15 of the 37 patients (40.54%) on comedication withdrew from etanercept treatment; this high rate of drug survival for etanercept (59.46%) demonstrated the substantial effect of comedication on treatment duration: without comedication more patients may have ceased etanercept treatment.

In conclusion, combination therapy is a possible option to improve long-term adherence to psoriasis treatment. The present study suggests that short-term comedication in association with etanercept may optimize clinical outcomes, with a positive risk : benefit ratio. Further prospective, larger studies are required to confirm these results, to overcome the limitations of a retrospective analysis from real-life routine practice.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding

Editorial assistance was provided by Ray Hill on behalf of HPS–Health Publishing and Services Srl and funded by Pfizer Italia.

References

- 1.Kimball AB, Jacobson C, Weiss S, et al. The psychosocial burden of psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2005; 6: 383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mrowietz U, Kragballe K, Reich K, et al. Definition of treatment goals for moderate to severe psoriasis: a European consensus. Arch Dermatol Res 2011; 303: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nijsten T, Margolis DJ, Feldman SR, et al. Traditional systemic treatments have not fully met the needs of psoriasis patients: results from a national survey. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 52: 434–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pathirana D, Ormerod AD, Saiag P, et al. European S3-guidelines on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009; 23(suppl 2): 1–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen P, Skov L, Zachariae C. Systemic combination treatment for psoriasis: a review. Acta Derm Venereol 2010; 90: 341–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cather JC, Crowley JJ. Use of biologic agents in combination with other therapies for the treatment of psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2014; 15: 467–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Driessen RJ, Boezeman JB, van de Kerkhof PC, et al. Three-year registry data on biological treatment for psoriasis: the influence of patient characteristics on treatment outcome. Br J Dermatol 2009; 160: 670–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mrowietz U, de Jong EM, Kragballe K, et al. A consensus report on appropriate treatment optimization and transitioning in the management of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014; 28: 438–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fredriksson T, Pettersson U. Severe psoriasis – oral therapy with a new retinoid. Dermatologica 1978; 157: 238–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, et al. Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum 2006; 54: 2665–2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esposito M, Gisondi P, Cassano N, et al. Survival rate of antitumour necrosis factor-α treatments for psoriasis in routine dermatological practice: a multicentre observational study. Br J Dermatol 2013; 169: 666–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]