Abstract

Objective

To evaluate salivary interleukin (IL)-1β levels in patients with psoriasis, before and after treatment with tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibitors.

Methods

In this pilot study, salivary secretions were collected from patients with psoriasis and untreated healthy control subjects at baseline, and from patients after 12 weeks’ treatment with TNF-α inhibitors. IL-1β levels were determined in saliva samples via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, undertaken before and after TNF-α inhibitor treatment. Psoriasis-specific analysis of disease severity and activity were also undertaken.

Results

At baseline, patients (n = 25) had significantly higher salivary IL1β levels than controls (n = 20). In patients with psoriasis, TNF-α inhibitor treatment resulted in significantly reduced IL1β levels compared with baseline, but IL1β levels remained significantly higher than in control subjects even after treatment. There was a positive correlation between IL-1β levels, psoriasis activity and disease index score after TNF-α inhibitor treatment.

Conclusion

Saliva is a valid noninvasive tool for monitoring inflammation in psoriasis. TNF-α inhibitor treatments appear to interfere with the oral inflammatory process in patients with psoriasis.

Keywords: IL-1β, psoriasis, oral biomarker, TNF-α inhibitor treatment

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic immune-mediated inflammatory disease with an estimated prevalence of up to 3% in the general population.1 The proinflammatory milieu plays a crucial role in the immunopathogenesis of psoriasis and links this disease to other inflammatory conditions, including metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, periodontitis and inflammatory bowel disease.2–5

Saliva, a biological fluid containing important biological markers, is easily collected and stored. Salivary biomarkers have been identified in systemic pathologies including cardiovascular disease, renal failure and malignancy.6,7 We have profiled the inflammatory cytokines present in salivary secretions from patients with psoriasis.8

The aim of this pilot study was to evaluate the change in salivary interleukin (IL)-1β concentration in patients with psoriasis after treatment with tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibitors.

Patients and methods

Study population

This pilot study recruited consecutive patients with stable chronic plaque psoriasis who were attending the Dermatology Clinic, Polytechnic University of Marche Region, Ancona, Italy, between January 2014 and March 2014. Inclusion criteria were no periodontal involvement and no previous biological therapy. Age, sex and periodontal status-matched control subjects were recruited from patients with nonpsoriatic dermatological conditions who were attending the same clinic. A trained oral pathologist (A.S.) evaluated the oral cavity of each participant. Patients with psoriasis then began standard regimens of TNF-α inhibitor treatment.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinski,9 and all study participants provided oral informed consent prior to enrolment.

Sample collection and analysis

Salivary secretion samples were collected at baseline (in patients and controls), and after 12 weeks of TNF-α inhibitor treatment (in the patient group). Samples were collected between 09:00 h and 11:00 h to control for circadian modification of salivary biomarkers, using a standardized collection method (Salivette®; Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany), and stored at –80°C until use. IL-1β levels were evaluated via an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Quiagen, Venlo, Netherlands) and expressed as absorbance units. Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scores10 were determined for each patient at baseline and at 12 weeks. Patients were stratified according to baseline psoriasis severity: mild (PASI ≤ 10); moderate (PASI > 10– ≤ 20); or severe (PASI > 20).

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean ± SD. For continuous variables, normality of distribution was verified using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and between-group comparisons were made using Kruskal–Wallis test. Linear regression analysis was used to model the relationship between tested variables. Patients were stratified according to baseline psoriasis severity: mild (PASI ≤ 10); moderate (PASI > 10– ≤ 20); severe (PASI > 20). All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism® version 5.0 and QuickCalcs® (both GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The study included 25 patients with psoriasis (15 male/10 female; mean age 50.2 ± 16.5 years; age range 34–66 years) and 20 control subjects (12 male/eight female; mean age 50.4 ± 15.5 years; age range 35–66 years). A total of 15 patients were treated with adalimumab (40 mg/every other week for 12 weeks); ten received etanercept 50 mg/bi-weekly for 12 weeks).

At baseline, seven patients had mild symptoms, 13 had moderate symptoms, and five had severe symptoms of psoriasis. TNF-α inhibitor treatment significantly reduced the PASI score compared with baseline in each patient group (P < 0.05 for each comparison; Table 1).

Table 1.

Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI)10 scores in patients with psoriasis stratified according to baseline disease severity, before and after 12 weeks of tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitor treatment (n = 25).

| PASI score | Mild disease groupa n = 7 | Moderate disease groupb n = 13 | Severe disease groupc n = 5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment | 6.4 ± 3.1 | 17.8 ± 2.2 | 23.5 ± 5.6 |

| After treatment | 1.1 ± 0.3d | 7.5 ± 2.1d | 11.2 ± 3.6d |

Data presented as mean ± SD.

Baseline PASI ≤ 10.

Baseline 10 < PASI ≤ 20.

Baseline PASI > 20.

P < 0.05 vs baseline; Kruskal–Wallis test.

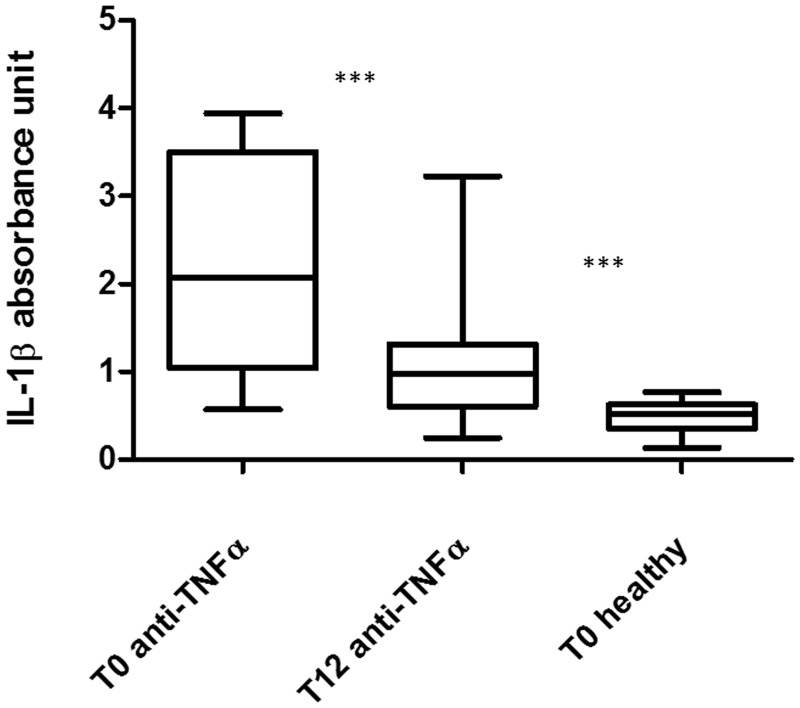

At baseline, patients had significantly higher salivary IL1β levels than controls (2.12 ± 1.16 vs 0.49 ± 0.17; P < 0.0001). TNF-α inhibitor treatment resulted in significantly reduced IL1β levels compared with baseline (1.15 ± 0.78 vs 2.12 ± 1.16; P < 0.0001), but IL1β levels remained significantly higher in patients with psoriasis than in healthy controls (1.15 ± 0.78 vs 0.49 ± 0.17; P = 0.0002) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Salivary interleukin (IL)-1 β levels in patients with psoriasis and controls. Tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitor treatment significantly reduced IL1β levels, compared with baseline (T0); however, IL1β levels remained significantly higher in patients with psoriasis than in healthy controls at the end of the 12-week treatment period (T12); ***P < 0.001; Kruskal–Wallis test.

There was no correlation between PASI score and IL-1β level at baseline. There was a significant positive correlation between PASI score and IL-1β level after TNF-α inhibitor treatment. (R2 0.21, P = 0.0028).

Discussion

Psoriasis is a multifactorial disease characterized by a chronic inflammatory process involving innate and adaptive immunity, leading to persistent activation of the immune response in epithelial surfaces and dysregulation of the host inflammatory response.5,11–13

Interleukin-1β is a key inflammatory molecule implicated in the immunopathogenesis of many inflammatory diseases, acting on epithelial cells, macrophages and fibroblasts. In psoriasis, IL-1β regulates chemokine expression and contributes to T-cell extravasation,14 and has been directly implicated in tissue destruction in other chronic inflammatory diseases such as periodontitis.15

The efficacy of TNF-α inhibitors in psoriasis is well documented, although evidence of their action on periodontal disease is scarce.16–19 Patients with psoriasis demonstrated higher levels of salivary IL-1β than healthy subjects in the present study, suggesting an increase in IL-1β production in this patient population. Interestingly, TNF-α inhibitor treatment reduced salivary IL-1β levels in our patients. This may attenuate the oral inflammatory process that could be a psoriasis trigger and/or perpetuate the persistent inflammatory process of psoriasis itself. Our study found that, despite being reduced by TNF-α inhibitor treatment, salivary IL-1β levels in patients remained higher than in control subjects. Taken together, these data suggest that salivary IL-1β may serve as a biomarker of disease activity in patients with psoriasis.

The main limitations of this study were the small sample size, and the comparative analysis with nonbiological agents. Although larger cohort studies are needed to validate our results, TNF-α agents appear to interfere with the oral inflammatory process in patients with psoriasis. In conclusion, saliva is a valid noninvasive tool for monitoring inflammation in psoriasis.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding

Editorial assistance was provided by Gayle Robins on behalf of HPS–Health Publishing and Services Srl and funded by Pfizer Italia.

References

- 1.Gudjonsson JE, Elder JT. Psoriasis: epidemiology. Clin Dermatol 2007; 25: 535–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gottlieb AB, Chao C, Dann F. Psoriasis comorbidities. J Dermatol Treat 2008; 19: 5–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen AD, Sherf M, Vidavsky L, et al. Association between psoriasis and the metabolic syndrome. A cross-sectional study. Dermatology 2008; 216: 152–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kimball AB, Robinson D Jr, Wu Y, et al. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors among psoriasis patients in two US healthcare databases, 2001–2002. Dermatology 2008; 217: 27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Preus HR, Khanifam P, Kolltveit K, et al. Periodontitis in psoriasis patients: a blinded, case-controlled study. Acta Odontol Scand 2010; 68: 165–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malamud D. Saliva as a diagnostic fluid. Dent Clin North Am 2011; 55: 159–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farnaud SJ, Kosti O, Getting SJ, et al. Saliva: physiology and diagnostic potential in health and disease. ScientificWorldJournal 2010; 10: 434–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganzetti G, Campanati A, Santarelli A, et al. Involvement of the oral cavity in psoriasis: results of a clinical study. Br J Dermatol 2015; 172: 282–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.41st World Medical Assembly. World Medical Association declaration of Helsinki. Recommendations guiding physicians in biomedical research involving human subjects. JAMA 1997; 277: 925–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langley RG, Ellis CN. Evaluating psoriasis with Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, Psoriasis Global Assessment, and Lattice System Physician’s Global Assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004; 51: 563–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sabat R, Philipp S, Hoflich C, et al. Immunopathogenesis of psoriasis. Exp Dermatol 2007; 16: 779–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganzetti G, Campanati A, Santarelli A, et al. Periodontal disease: an oral manifestation of psoriasis or an occasional finding? Drug Dev Res 2014; 75(Suppl 1): S46–S49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orciani M, Campanati A, Salvolini E, et al. The mesenchymal stem cell profile in psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2011; 165: 585–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buerger C, Richter B, Woth K, et al. Interleukin-1β interferes with epidermal homeostasis through induction of insulin resistance: implications for psoriasis pathogenesis. J Invest Dermatol 2012; 132: 2206–2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sawada S, Chosa N, Ishisaki A, et al. Enhancement of gingival inflammation induced by synergism of IL-1β and IL-6. Biomed Res 2013; 34: 31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campanati A, Giuliodori K, Ganzetti G, et al. A patient with psoriasis and vitiligo treated with etanercept. Am J Clin Dermatol 2010; 11(Suppl 1): 46–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campanati A, Ganzetti G, Di Sario A, et al. The effect of etanercept on hepatic fibrosis risk in patient with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, metabolic syndrom and psoriasis. J Gastroenterol 2013; 48: 839–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmitt J, Rosumeck S, Thomaschewski G, et al. Efficacy and safety of systemic treatments for moderate-to-severe psoriasis: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Dermatol 2014; 170: 274–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobayashi T, Yokoyama T, Ito S, et al. Periodontal and serum protein profiles in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab. J Periodontol 2014; 85: 1480–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]