Abstract

Objective

To investigate the incidence of insulin resistance (IR) and diabetes in patients with chronic hepatic schistosomiasis japonica (HSJ) and portosystemic shunts (PSS).

Methods

Pre- and post-contrasted computed tomography images obtained from patients with HSJ and control subjects were reviewed by two radiologists who identified and graded any shunting vessels. Anthropometric measurements, hepatic enzymes, lipid profile, blood levels of albumin, glucose, insulin and homeostasis model assessment (HOMA-2) index of all participants were also assessed.

Results

Fifty-two patients with HSJ and 30 control subjects were involved in the study. The coronary, short gastric and perisplenic veins were the most common shunting vessels. There were no significant differences between patients and controls in terms of body mass index or liver function. The degree of shunting vessels, blood glucose, oral glucose tolerance test120/0, insulin, HOMA-2 index, glycosylated haemoglobin, cholesterol, high- and low-density lipoprotein, and C-reactive protein were significantly higher in the patients with IR. A positive correlation was found between the degree of the shunting vessels and the HOMA-2 index.

Conclusions

Patients with chronic HSJ and PSS without liver dysfunction had a high incidence of IR and diabetes. The study showed that PSS and IR are related and therefore patients with PSS should be screened for IR and vice versa.

Keywords: Hyperinsulinaemia, insulin resistance, diabetes, portosystemic shunts, hepatic schistosomiasis japonica

Introduction

Insulin resistance (IR) is associated with cirrhosis regardless of its cause including alcohol, hepatitis C infection or cholestatic liver disease.1,2 IR is thought to occur as a consequence of liver dysfunction, which has an important impact on glucose metabolism.2,3 However, recent studies have demonstrated that portal hypertension and portosystemic shunts (PSS) are also factors that contribute to IR.4–6 Portal hypertension is the most common complication of cirrhosis and can lead to PSS3 and several reports suggest that PSS are the major cause of IR.7,8

Measuring portal pressure is difficult to perform in routine clinical practice because it is an invasive procedure that is dependent on the physician’s skill.5,6 However, computed tomography (CT) can be used as a non-invasive tool for evaluating portal pressure indirectly by measuring the degree of shunting vessels.9

Schistosomiasis affects more than 230 million people worldwide and remains a major public health problem in many developing countries.10 In 2009, approximately 65 million people in China were at risk of infection and 0.36 million individuals were infected.10 Although the majority of patients with primary hepatic schistosomiasis japonica (HSJ) are completely cured, its sequelae irreversibly develop into progressive periportal fibrosis that can lead to portal hypertension and PSS.11 Many patients with HSJ are clinically neglected because they typically do not exhibit any obvious signs or symptoms and tend to visit the hospital only after developing serious complications, which are usually due to PSS (e.g., upper gastrointestinal bleeding or hepatic encephalopathy).11,12 To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has focused on the changes in glucose metabolism in patients with chronic HSJ. Therefore, the aim of this current study was to investigate the incidence of IR and diabetes in patients with chronic HSJ and PSS.

Patients and methods

Study population

From March 2014 to September 2015, patients with a history of HSJ were recruited from Jinshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China, which is located in a former HSJ endemic region. The disease was confirmed by combining the findings of a typical liver ultrasonography with results of clinical tests and a history of infection. Active schistosomiasis was diagnosed by positive Kato-Katz test.13 Exclusion criteria included active schistosomiasis, history of viral hepatitis, alcoholism, hepatocellular carcinoma, primary hypertension, type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes in first-degree relatives (i.e., to avoid genetic factors). Healthy volunteers served as control subjects. The control subjects were recruited from the local population attending a clinic for routine examination (Department of Physical Examination Centre, Jinshan Hospital, Jinshan, Shanghai).

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jinshan Hospital of Fudan University, Shanghai, China (No. 201403) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants before CT imaging and laboratory tests were performed.

Clinical data collection

After a 12-h fast, blood samples were collected from all participants and analysed for levels of insulin, glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c), triglycerides (TG), cholesterol (Cho), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and C-reactive protein (CRP), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total bilirubin (TB), prothrombin time (PT) and albumin (Alb) using standard biochemical procedures. After the samples were collected, each participant underwent an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). For this test, the participant received 75 g glucose orally and plasma glucose was measured at 0, 60 and 120 min. The difference between the 120 min and 0 min glucose levels (OGTT 120/0) was calculated.

The body mass index (BMI) was calculated as follows: BMI = mass/height2. Insulin resistance was determined using the updated homeostasis model assessment (HOMA-2) index.5 Using the HOMA-2 calculator (http://www.dtu.ox.ac.uk/homacalculator/), steady state β-cell function (%B), insulin sensitivity (%S) and HOMA-2 index were calculated. Patients with a HOMA-2 index > 2 were considered to have IR.

CT image analyses

Pre- and post-contrasted CT images in the arterial and portal phase were taken for all participants using a 128-slice CT scanner (SOMATOM®; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). Ultravist® contrast medium was used (370 mg I/ml; Bayer Healthcare, Berlin, Germany) and administered intravenously at a dose of 2 ml/kg and at a rate of 3 ml/s. The parameters were as follows: 120 kV tube voltage; 200 mA tube current; 0.6 mm collimation; 1.0-mm slice thickness; 0.6 mm interval; and 1 pitch. The scanning range extended from above the diaphragm to the inferior pole of the right kidney.

All of the imaging data were reconstructed by two radiologists (i.e., one author [Y.L.] and the other an independent assessor) who were blinded to participant information. The axial and coronal thin-slab (10 mm) multiplanar reformations of the portal phase were reconstructed and observed by scrolling the mouse at a workstation (Syngo; Siemens). The presence, anatomy and grade of the shunting vessels were evaluated according to the procedures described in previous reports.14–16 The degree of a shunting was evaluated using a four-point scale (i.e., 0, no shunting vessels; 1, mild dilatation of a shunting vessel; 2, moderate dilatation (round) of a shunting vessel; 3, significant dilatation (tubular or serpentine) of a shunting vessel.14 For each patient, the total score for all shunting vessels was calculated independently by the two radiologists and the mean of the two scores was used to indicate the degree of shunting.

Statistical analyses

The sample size was estimated using a clinical research sample size calculator (CRESS V1.3). Although only 19 patients with HSJ and 19 control subjects were required to detect a significant difference in HOMA-2 IR between the two groups with α = 0.05 and β = 0.1, the study recruited as many subjects that became available in the study duration period.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS® version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows®. One-way analysis of variance was used for the laboratory tests and the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test was used to evaluate the degree of the shunting vessels. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was used to determine the correlation between the degree of the shunting vessels and HOMA-2 index or diabetes. Agreement between the two radiologists was estimated by calculating κ statistics and was interpreted as follows: < 0.40, fair agreement; 0.41–0.60, moderate agreement; 0.61–0.80, substantial agreement; and 0.81–1.00, almost perfect agreement.17 A probability level of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Of the 135 patients with HSJ that were recruited to the study, 83 were excluded (active schistosomiasis [n = 1], history of viral hepatitis [n = 45], alcoholism [n = 2], hepatocellular carcinoma [n = 8], primary hypertension [n = 11], type 1 diabetes or type 2 diabetes in first-degree relatives [n = 16]). Therefore, 52 patients (25 men, 27 women) were enrolled into the study; their ages ranged from 58 to 89 years (mean ± SD, 73.7 ± 7.8 years). All patients had HSJ and had been cured for more than 35 years. Schistosoma japonicum eggs were not detected in the faeces of any of the patients. Previous upper digestive bleeding had been recorded in 31 patients (60%) but none of them had experienced a bleed within the previous 3 months. Splenomegaly was found in 25 patients (48%) and ascites in three patients (6%). Neurological symptoms, such as deficits in attention, disturbance of sleep, rigidity and tremor were observed in 22 (42%).

According to plasma glucose levels, results of the OGTT and the HOMA-2 index, patients were subdivided into the following groups: non-IR (n = 17), IR without diabetes (n = 16), and IR with diabetes (n = 19). Thirty healthy volunteers (mean ± SD age, 72.6 ± 9.3 years; 10 men, 20 women) served as age-matched control subjects.

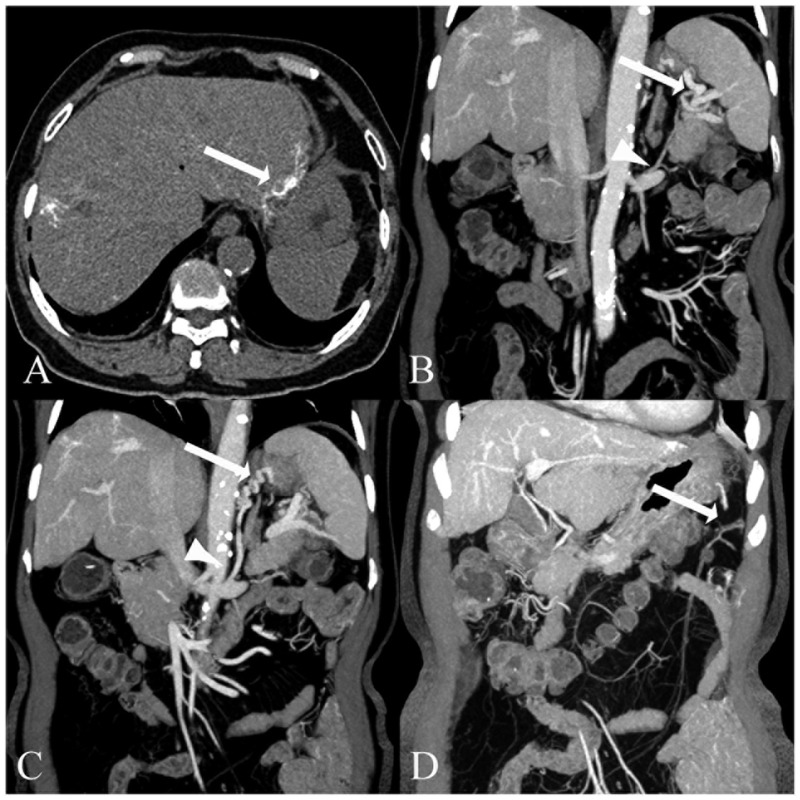

Typical long stripes of strong echo or hyperdense calcification in the liver were seen on ultrasound or CT images of the patients with HSJ. The anatomical types and the frequency of the shunting vessels in the 52 patients with HSJ are shown in Table 1. Thirteen types of shunting vessels (i.e., coronary, gastroepiploic, oesophageal, para-oesophageal, short gastric, perisplenic, splenorenal, gastrorenal, paraumbilical, abdominal wall vein, retroperitoneal-paravertebral, mesenteric and omental) were identified and graded. The coronary vein, short gastric vein, perisplenic vein, gastroepiploic vein, and splenorenal vein were the five most frequent vessels of PSS and were found in at least 50% of the patients. Vessels wider than 6 mm were clearly observed and could be distinguished from the lymph nodes on post-contrasted CT images (Figure 1). The κ statistics agreement between the two radiologists was 0.80 and so the interobserver agreement was substantial. A mild, moderate and significant degree of the shunting vessels was observed in 14, 31 and 7 patients, respectively.

Table 1.

Types and frequency of the shunting vessels detected by computed tomography (CT) imaging in the 52 patients with chronic hepatic schistosomiasis japonica as determined by two independent radiologists.

| Type of shunting vessels | Radiologist 1 (n) | Radiologist 2 (n) | Mean frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary vein | 43 | 44 | 83.7 |

| Short gastric vein | 36 | 34 | 67.3 |

| Perisplenic vein | 35 | 34 | 66.3 |

| Gastroepiploic vein | 33 | 31 | 61.5 |

| Splenorenal vein | 27 | 25 | 50.0 |

| Para-oesophageal vein | 26 | 21 | 45.2 |

| Oesophageal vein | 22 | 24 | 44.2 |

| Gastrorenal vein | 23 | 18 | 39.4 |

| Retroperitoneal-paravertebral vein | 19 | 18 | 35.6 |

| Mesenteric vein | 17 | 16 | 31.7 |

| Omental vein | 16 | 15 | 29.8 |

| Paraumbilical vein | 16 | 13 | 27.9 |

| Abdominal wall vein | 12 | 11 | 22.1 |

Figure 1.

Computed tomography (CT) images from a 73-year-old patient with chronic hepatic schistosomiasis japonica and portosystemic shunts. (A) The pre-contrasted CT image shows the multiple long stripes of calcifications (arrow). (B) The coronal thin-slab multiplanar reformations of the post-contrasted CT image show the shunting vessel of the splenorenal vein (arrow and arrowhead), (C) gastrorenal vein (arrowhead), gastroepiploic vein (arrow) and (D) a shunting vessel extending from the mesenteric vein to the spleen vein (arrow).

There were no statistically significant differences between all four study groups in terms of BMI or liver function (i.e., ALT, AST, TB, TG, Alb) (Table 2). The degree of the shunting vessels, plasma glucose, OGTT120/0, plasma insulin, HOMA-2 index, HbA1c, Cho, HDL, LDL, and CRP were significantly different between the patients with IR and the control subjects (see Table 2 for the specific details of the significant between-group differences; P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Clinical features and biochemical parameters of patients (n = 52) with chronic hepatic schistosomiasis japonica (with and without insulin resistance) and healthy control subjects (n = 30).

| Characteristic | Chronic HSJ patients (n = 52) |

Control subjects (n = 30) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-IR (n = 17) | IR without diabetes (n = 16) | IR with diabetes (n = 19) | ||

| Age, years | 74.8 ± 7.8 | 73.9 ± 6.1 | 72.6 ± 8.0 | 72.6 ± 10.0 |

| Degree of shunting vessels, n | 3.7 ± 2.2 | 7.4 ± 2.5*# | 9 ± 3.0*# | 0 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 21.1 ± 7.0 | 21.7 ± 8.0 | 22.7 ± 8.6 | 20.2 ± 5.4 |

| Glucose, mmol/l | 5.6 ± 0.6 | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 10.2 ± 3.1*# | 5.3 ± 0.7 |

| OGTT120/0 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 2.0 ± 0.3*# | 2.4 ± 0.2*# | 1.2 ± 0.3 |

| Insulin, pmol/l | 90 ± 9.5 | 230.5 ± 67.6*# | 217.3 ± 149.0*# | 87.4 ± 24.0 |

| HOMA-2 %B | 114 ± 25.6 | 224.6 ± 77.9*# | 83.5 ± 61.4 | 122.4 ± 33.5 |

| HOMA-2 %S | 59.1 ± 5.9 | 26 ± 8.3*# | 35.2 ± 25.0*§ | 66.2 ± 20.7 |

| HOMA-2 IR | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 1.1*# | 4.4 ± 2.7*# | 1.6 ± 0.5 |

| HbA1c, % | 6.3 ± 1.4 | 6.3 ± 1.0 | 8.8 ± 3.1*# | 5.6 ± 0.6 |

| ALT, IU/l | 20.4 ± 10.0 | 18.4 ± 8.0 | 21.6 ± 14. 7 | 17.8 ± 8.0 |

| AST, IU/l | 25 ± 9.0 | 20.1 ± 7.5 | 23.9 ± 10.6 | 20.7 ± 6.9 |

| PT, s | 13.5 ± 2.0 | 13.2 ± 2.4 | 13.5 ± 2.3 | 13.2 ± 1.8 |

| TB, µmol/l | 25.3 ± 13.9 | 26.2 ± 13.9 | 24.3 ± 14.3 | 22.0 ± 11.3 |

| Albumin, g/l | 34.6 ± 4.1 | 35.2 ± 3.4 | 34.8 ± 3.8 | 37.0 ± 4.7 |

| TG, nmol/l | 1.6 ± 2.3 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 1.6 ± 0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.3 |

| Cho, nmol/l | 3.8 ± 0.6 | 3.5 ± 1.1 | 5.1 ± 1.6*§ | 3.6 ± 1.0 |

| HDL, nmol/l | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.4¥ | 0.8 ± 0.4ɸ | 1.2 ± 0.4 |

| LDL, nmol/l | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 3.2 ± 0.9*# | 2.2 ± 0.6 |

| CRP, ng/ml | 9.6 ± 12.5 | 14.2 ± 14.9¥ | 12.0 ± 20.4¥ | 2.3 ± 2.0 |

Values are shown as mean ± SD.

§P < 0.01, #P < 0.001 compared with non-IR group; one-way analysis of variance and Kruskal–Wallis test.

¥P < 0.05, ɸP < 0.01, *P < 0.001 compared with control subjects; one-way analysis of variance and Kruskal–Wallis test.

HSJ, hepatic schistosomiasis japonica; IR, insulin resistance; BMI, body mass index; OGTT120/0, ratio between 120 min and 0 min glucose levels during oral glucose tolerance test; HOME-2, homeostasis model assessment index; HOMA-2%B, homeostasis model assessment steady state β-cell function; HOMA-2%S, homeostasis model assessment insulin sensitivity; HOMA-2 IR, subjects with IR; HbA1c, glycosylated haemoglobin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; PT, prothrombin time; TB, total bilirubin; TG, triglycerides; Cho, cholesterol; HDL, high-density lipoproteins; LDL, low-density lipoproteins; CRP, C-reactive protein; IU, international units.

Compared with non-IR patients, there were significantly more shunts and higher OGTT120/0 levels, insulin concentrations and HOMA-2 index values in patients with IR (see Table 2 for the specific details of the significant between-group differences; P < 0.05).

Patients with diabetes had significantly higher glucose, HbA1c, Cho and LDL levels compared with non-IR patients and significantly higher glucose, HbA1c, Cho, LDL and CRP compared with control subjects (P < 0.05 for all comparisons). Significantly lower HDL and higher CRP values were observed in all patients with IR (i.e., with and without diabetes) compared with the control subjects (P < 0.05 for all comparisons).

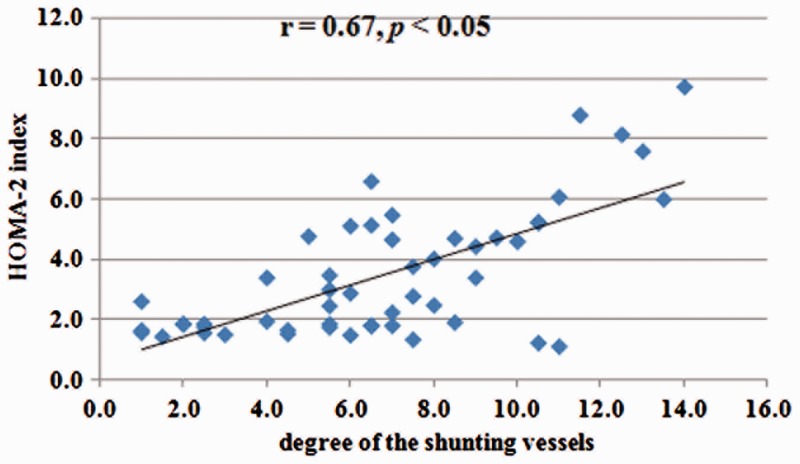

The correlation between the degree of the shunting veins and HOMA-2 index is shown in Figure 2. A significant positive correlation was found between the degree of shunting vessels and the HOMA-2 index (r = 0.67; P < 0.05; Spearman's rank correlation coefficient). In addition, multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that HDL levels were correlated with IR (r = –0.34 and P < 0.05; data not shown).

Figure 2.

Scatter graph showing the change in the homeostasis model assessment (HOMA-2) index with the increase in the degree of shunting from the 52 patients with hepatic schistosomiasis japonica. A positive correlation was seen between the two variables (r = 0.67; P < 0.05; Spearman's rank correlation coefficient).

Discussion

This present study demonstrated that in patients with chronic HSJ and normal liver function with PSS there was a high incidence of IR and diabetes; 67% of patients had IR and 37% had diabetes. These findings are similar to a previous study in cirrhotic patients that showed a 60% to 80% prevalence of IR and a 30% prevalence of diabetes.4 In patients with chronic HSJ with IR and normal plasma glucose in the present study, the function of β-cells was upgraded resulting in a statistically significantly higher HOMA-2 %B value compared with non-IR patients or control subjects. In these patients, the combination of sufficient insulin secreted by the pancreas to reduce the amount of glucose and the decreased insulin clearance due to PSS lead to hyperinsulinaemia. With the progression of the disease, the pancreas would ‘burn out’ and hyperglycaemia and hyperlipidaemia would ensue.18 An interesting observation was that the CRP level was elevated in all patients with chronic HSJ compared with control subjects, which is suggestive of systemic inflammation.19

Liver dysfunction is generally perceived to be the main contributing factor of IR because of a decrease in hepatic insulin clearance.1 However, the aetiology of IR in these patients is unclear because portal hypertension and PSS are common complications in cirrhotic patients and they may also contribute to the IR.4–6

One study showed that in patients with chronic HSJ, the primary pathological changes were marked periportal fibrosis, relatively intact hepatic sinusoids and slight hepatocyte injuries that are different from those in cirrhosis or other liver diseases.20 These pathological changes lead to portal hypertension and subsequent PSS.3 In the present study, all patients with chronic HSJ had a normal liver function, which was consistent with findings from our previous study.12 A lack of correlation between IR and liver histological severity in cirrhotic patients has been reported elsewhere.21,22 Therefore, we hypothesize that IR in patients with chronic HSJ might be caused by portal hypertension and subsequent PSS rather than by liver dysfunction.

This present study confirmed that CT imaging can be used to evaluate the degree of shunting vessels.9 A positive correlation was found between the degree of shunting vessels and the HOMA-2 index. The most frequent shunting vessels were the coronary vein, short gastric vein, perisplenic vein, gastroepiploic vein, and splenorenal vein, which cannot be evaluated by endoscopy.14 Therefore, when a patient with chronic HSJ and PSS is identified, regardless of liver function, IR or diabetes should be considered and investigated. Conversely, in an HSJ endemic region, in any patient with IR or diabetes, PSS should be considered as a contributing factor in their pathogenesis.

The present study had several limitations. First, patients with HSJ and PSS often lack clinical features and so some patients without a clear history of schistosomiasis may have unintentionally been excluded from the study so creating a population bias. Secondly, elevated CRP was found in patients with HSJ and IR but no clinical features of systemic inflammation were found in these patients. Further studies are required to confirm these current findings.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that patients with chronic HSJ and PSS without liver dysfunction had a high incidence of IR and diabetes. Additionally, the study showed that PSS and IR are related and so patients with PSS should be screened for IR and vice versa.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research was supported by Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (No. 2014-658).

References

- 1.Baig NA, Herrine SK, Rubin R. Liver disease and diabetes mellitus. Clin Lab Med 2001; 21: 193–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Billeter AT, Senft J, Gotthardt D, et al. Combined non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus: sleeve gastrectomy or gastric bypass?-a controlled matched pair study of 34 patients. Obes Surg 2016; 26: 1867–1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berzigotti A, Abraldes JG. Impact of obesity and insulin-resistance on cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 36: 527–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cammà C, Petta S, Di Marco V, et al. Insulin resistance is a risk factor for esophageal varices in hepatitis C virus cirrhosis. Hepatology 2009; 49: 195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erice E, Llop E, Berzigotti A, et al. Insulin resistance in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2012; 302: G1458–G1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Francque S, Verrijken A, Mertens I, et al. Visceral adiposity and insulin resistance are independent predictors of the presence of non-cirrhotic NAFLD-related portal hypertension. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011; 35: 270–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishikawa T, Shiratsuki S, Matsuda T, et al. Occlusion of portosystemic shunts improves hyperinsulinemia due to insulin resistance in cirrhotic patients with portal hypertension. J Gastroenterol 2014; 49: 1333–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Su AP, Cao SS, Le Tian B, et al. Effect of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt on glycometabolism in cirrhosis patients. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2012; 36: 53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu K, Meng X, Pang P, et al. Gastric varices in patients with portal hypertension: evaluation with multidetector row CT. J Clin Gastroenterol 2010; 44: e108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu J, Zhu C, Shi Y, et al. Surveillance of schistosoma japonicum infection in domestic ruminants in the Dongting Lake region, Hunan province, China. PLoS One 2012; 7: e31876–e31876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farias AQ, Kassab F, da Rocha EC, et al. Propranolol reduces variceal pressure and wall tension in schistosomiasis presinusoidal portal hypertension. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 24: 1852–1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y, Qiang JW, Ju S. Brain MR imaging changes in patients with hepatic schistosomiasis japonicum without liver dysfunction. Neurotoxicology 2013; 35: 101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao CL, Bao ZP, Li SZ, et al. Schistosomiasis in a migrating population in the lake region of China and its potential impact on control operation. Acta Trop 2015; 145: 88–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim SH, Kim YJ, Lee JM, et al. Esophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis: multidetector CT esophagography – comparison with endoscopy. Radiology 2007; 242: 759–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takaji R, Kiyosue H, Matsumoto S, et al. Partial thrombosis of gastric varices after balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration: CT findings and endoscopic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011; 196: 686–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiyosue H, Ibukuro K, Maruno M, et al. Multidetector CT anatomy of drainage routes of gastric varices: a pictorial review. Radiographics 2013; 33: 87–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mak HK, Yau KK, Chan BP. Prevalence-adjusted bias-adjusted kappa values as additional indicators to measure observer agreement. Radiology 2004; 232: 302–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vollenweider P, von Eckardstein A, Widmann C. HDLs, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2015; 224: 405–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Artese HP, Foz AM, Rabelo Mde S, et al. Periodontal therapy and systemic inflammation in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015; 10(5): e0128344–e0128344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Da Silva LC. Portal hypertension in schistosomiasis: pathophysiology and treatment. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1992; 87(Suppl 4): 183–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petrides AS, Riely CA, DeFronzo RA. Insulin resistance in noncirrhotic idiopathic portal hypertension. Gastroenterology 1991; 100: 245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park SH, Kim DJ, Lee HY. Insulin resistance is not associated with histologic severity in nondiabetic, noncirrhotic patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104: 1135–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]