Abstract

Objective

To assess diabetes self-care behaviours and health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) in people with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), in China.

Methods

Individuals with T1DM underwent face-to-face interviews over a 7-day questionnaire period. The Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities (SDSCA) was used to assess self-care behaviours. EQ-5D-3L was used to quantify HRQoL.

Results

Of self-care activities, individuals (n = 322) were most likely to adhere to treatment and least likely to perform foot care. A total of 78.9% of participants did not examine their feet and 33.9% of participants did not monitor blood glucose during the questionnaire period. Moderate/severe anxiety or depression was reported by 28.6% of participants; 23.9% reported moderate/severe pain or discomfort. The individual’s level of diabetes education, insulin injection regimen and HbA1c were independently associated with total SDSCA score. Household income and age were independently associated with EQ-5D index.

Conclusions

Enhancing diabetes education in individuals and implementing strict insulin regimens could improve self-care behaviours in people with T1DM in China.

Keywords: Diabetes self-care activities, health-related quality-of-life, type 1 diabetes mellitus, summary of diabetes self-care activities, 3C study

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is a major chronic disease in children and adolescents, the prevalence of which is increasing globally, particularly in Asia.1 A 2011 study by the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) to investigate the coverage, cost and care of T1DM in China (3C study), found an incidence of 1.1–1.5 cases per 100 000 children per year.2,3 In addition, the mean glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level in people with T1DM in Shantou, China, was found to be ∼10%,4 which is higher than the recommended levels of <7.5% in children/adolescents and <7% in adults,5,6 possibly due to a lack of day-to-day diabetes management. Self-care is important to maintain optimal glycaemic control and prevent complications,7 including both microvascular (e.g. retinopathy and neuropathy) and macrovascular complications (e.g. myocardial infarction, angina pectoris and stroke), which can negatively affect health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL)8,9 and have fatal consequences.10 Self-care requires frequent monitoring of blood glucose levels (at least three times per day), monitoring and controlling carbohydrate intake, frequent insulin administration (four injections per day or infusion via pump), altering insulin dose to match diet and activity patterns, participating in moderate-intensity physical activity for ≥150 min per week, and checking urine for ketones when necessary.7

Living with T1DM affects the psychological and emotional wellbeing of affected individuals and their families. HRQoL assesses the individual’s perception of health and is a useful measure of overall disease burden. It is a multidimensional concept, comprising physical, emotional and social components.8 The most important outcome measure in T1DM may not be glycaemic control, but perceived HRQoL.11 People with T1DM may have varying HRQoL burdens at different life stages, such as loss of flexibility or overprotection in childhood, future worries and school work in adolescence, and work, marriage and reproduction issues in adulthood. In addition, diabetes self-care behaviours is closely associated with metabolic control,12 but it is unclear which behaviours have the most influence over glycaemic control. Understanding the factors influencing self-care behaviours and HRQoL will help healthcare providers design interventions to improve the wellbeing of people with T1DM.13,14

The aim of the present study was to assess self-care behaviours and HRQoL of individuals with T1DM who participated in the 3C study at the Shantou Centre.2,3 It was hypothesized that these people were weak in some aspects of self-care, that diabetes had a negative effect on HRQoL, that self-care behaviours and HRQoL varied between people at different life stages, and that some controllable influencing factors could be identified that could guide clinical management.

Participants and methods

Study population

The study was designed by the IDF2 and included primary (four in Beijing, two in Shantou), secondary (three in Beijing, two in Shantou), and tertiary (six in Beijing, two in Shantou) health care facilities with active diabetes outpatient clinics and the willingness and capacity to participate in the study. Study subjects were recruited sequentially from outpatient clinics and inpatient wards, or by invitation from a list of people diagnosed with T1DM in a 3-year retrospective record review. Participants or their parent(s) (if <15 years of age) underwent face-to-face, personal, interviews. People aged <6 months at T1DM diagnosis were excluded.

This analysis included people from health care facilities in Shantou. Trained investigators performed interviews during July/September 2011 and January/February 2012; the questionnaire period covered 7 days. Venous blood samples were taken and tested for HbA1c at local hospital laboratories using pressurized liquid chromatography. Detailed project design and implementation information was as described.2

The study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of Shantou University Medical College, Shantou, China. All participants provided written informed consent.

SDSCA

Diabetes self-care activities were assessed using the Chinese version of the Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities (SDSCA) questionnaire, which has been showed to have high reliability and validity.15 Scores were calculated for six items: following a healthy diet; physical activity; adherence to recommended medications; self-monitoring of blood glucose; foot care; smoking. Using a continuous scale ranging between 0 and 7, the numerical scoring of items was based on the number of days of the week that the behaviour was performed; the mean of each item score was determined to find an overall score for each self-care activity. Since smoking is uncommon in children and adolescents in China16 this parameter was not included in the present study.

EQ-5D

Health-related quality-of-life was assessed using EQ-5D-3L, a standardized scale used in a wide range of health conditions and treatments as well as in the general population.17 Respondents classify their health status at three levels of severity (no, moderate, or severe problems) in five dimensions (mobility; self-care; usual activities; pain/discomfort; anxiety/depression), resulting in scores that can be converted into a single index value for health status (1 = full health; 0 = dead). The index value was assigned using a Japanese time trade-off value set,18 since no Chinese value set is available. Participants also completed the EQ-VAS, which records self-rated health on a visual analogue scale ranging between 100 (best imaginable health state) and 0 (worst imaginable health state).

Statistical analyses

The sample size of the 3C study was calculated by the IDF, who determined that a minimum of 320 participants were required at each study centre (Beijing and Shantou).2

Data were presented as median (25th, 75th quartile), mean ± SD or n (%). Differences and associations between variables were analysed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), multiple ANOVA, χ2-test or Spearman’s product-moment correlation. Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s α-coefficient, and the coefficients of the SDSCA and EQ-5D questionnaires were 0.72 and 0.77, respectively. Multiple linear regression analysis was used to identify factors associated with total SDSCA score and EQ-5D index. Independent variables included age, sex, diabetes duration, household income, residence, presence/absence of medical insurance, number of daily insulin injections, HbA1c level, presence/absence of group diabetes education, and presence/absence of individual diabetes education. The significant variables were included in a forward stepwise approach. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS® version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows®. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The study included 322 participants (158 male/164 female; median age 23 [16, 33] years; age range 3–65 years). Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of people with type 1 diabetes mellitus in Shantou, China, included in a study evaluating self-care behaviours and health-related quality-of-life (n = 322)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Male | 158 (49.1) |

| Age, years | 23 (16, 33) |

| <13 | 53 (16.5) |

| 13–20 | 80 (24.8) |

| >20 | 189 (58.7) |

| Disease duration, years | 3 (1, 6) |

| <5 | 199 (61.8) |

| 5–9 | 77 (23.9) |

| ≥10 | 46 (14.3) |

| Household income, US$/year | |

| <3000 | 289 (89.8) |

| 3000–10000 | 29 (9.0) |

| >10000 | 4 (1.2) |

| Medical insurance | 289 (89.8) |

| Only child | 105 (32.6) |

| Residence | |

| Urban | 109 (33.9) |

| Rural | 213 (66.1) |

| Insulin dose, IU/kg | 0.72 ± 0.29 |

| HbA1c, % | 9.97 ± 2.72 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 18.36 ± 4.73 |

| Diabetes education | |

| Individual | 22 (6.8) |

| Group | 86 (26.7) |

| None | 214 (66.5) |

| Number of daily insulin injections | |

| 1–3 | 286 (88.8) |

| 4/pump infusion | 36 (11.2) |

Data presented as n (%), median (25%, 75% quartile) or mean ± SD.

Data regarding SDSCA and EQ-5D scores are shown in Table 2. Of the self-care activities, participants were most likely to adhere to treatment and least likely to perform foot care. During the 7 days included in the questionnaire period, 254/322 participants (78.9%) did not examine their feet and 109/322 participants (33.9%) did not monitor blood glucose. Moderate/severe anxiety or depression was reported by 92/322 participants (28.6%) and 77/322 (23.9%) reported moderate/severe pain or discomfort.

Table 2.

Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities (SDSCA) and health-related quality-of-life (EQ-5D scale) data in people with type 1 diabetes mellitus in Shantou, China (n = 322)

| Data sett | Value |

|---|---|

| SDSCA15 | |

| Healthy diet | 4.25 ± 1.7 |

| Physical activity | 3.14 ± 2.4 |

| SMBG | 2.45 ± 2.6 |

| Foot care | 0.78 ± 1.7 |

| Adherence to treatment | 4.69 ± 2.1 |

| Total | 39.12 ± 13.3 |

| EQ-5D17 | |

| Mobility difficulties, none/moderate/severe | 289/27/6 (89.8/8.4/1.9) |

| Self-care difficulties, none/moderate/severe | 305/14/3 (94.7/4.3/0.9) |

| Usual activity difficulties, none/moderate/severe | 293/26/3 (91.0/8.1/0.9) |

| Pain/discomfort, none/moderate/severe | 245/74/3 (76.1/23.0/0.9) |

| Anxiety/depression, none/moderate/severe | 230/90/2 (71.4/28.0/0.6) |

| EQ-VAS | 75.02 ± 18.5 |

| EQ-5D index | 0.79 ± 0.1 |

Data presented as mean ± SD or n (%).

VAS, visual analogue scale.

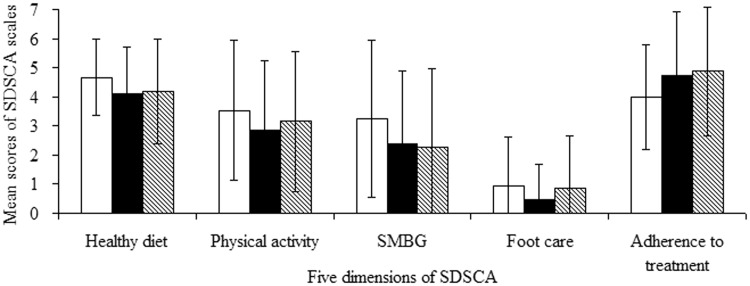

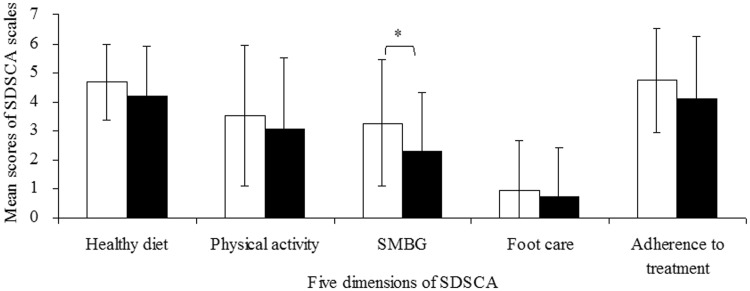

There were no significant between-group differences in self-care behaviours when participants were stratified by age (children aged <13 years [n = 53]; adolescents aged 13–20 years [n = 80]; adults aged >20 years [n = 189]; Figure 1). When participants were stratified according to HbA1c, adherence to self-monitoring of blood glucose was significantly higher in participants with HbA1c ≤ 7.5% (n = 61) than in those with HbA1c > 7.5% (n = 261; P < 0.05; Figure 2). There were no statistically significant between-group differences in any other SDSCA parameter.

Figure 1.

Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities (SDSCA)15 data in people with type 1 diabetes mellitus in Shantou, China, stratified according to age (children aged <13 years [n = 53; white bars]; adolescents aged 13–20 years [n = 80; black bars]; adults aged >20 years [n = 189; striped bars]). SMBG, self-monitoring of blood glucose.

Figure 2.

Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities (SDSCA)15 data in people with type 1 diabetes mellitus in Shantou, China, stratified according to glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c ≤ 7.5% [n = 61; white bars]; HbA1c > 7.5% [n = 261; black bars]). *P < 0.05; one way analysis of variance. SMBG, self-monitoring of blood glucose.

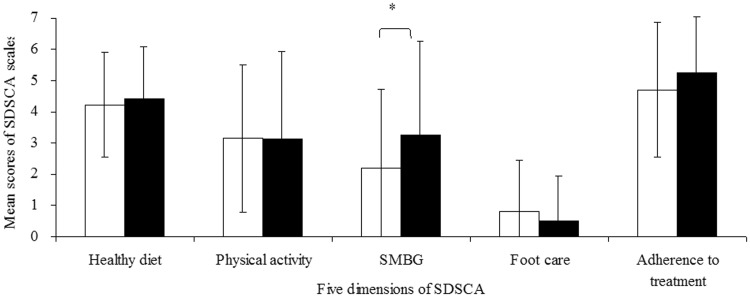

Self-care data for participants stratified according to insulin treatment regimen are shown in Figure 3. Adherence to self-monitoring of blood glucose was significantly higher in participants receiving ≥3 daily injections/pump infusion (n = 209), compared with those receiving <3 daily injections (n = 113; P < 0.05). There were no other statistically significant between-group differences.

Figure 3.

Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities (SDSCA)15 data in people with type 1 diabetes mellitus in Shantou, China, stratified according to insulin injection regimen (<3 daily injections [n = 209; white bars]; ≥3 daily injections/pump infusion [n = 113; black bars]). *P < 0.05; one way analysis of variance. SMBG, self-monitoring of blood glucose.

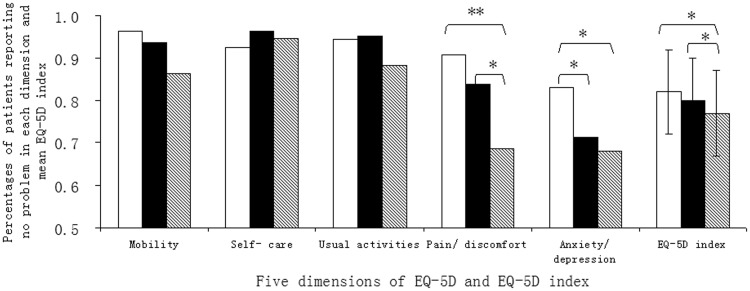

Data regarding EQ-5D in people stratified by age are shown in Figure 4. EQ index was significantly lower in adults than in both children and adolescents (P < 0.05 for each comparison). Children and adolescents had significantly better HRQoL related to pain and discomfort than adults (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively), and children had significantly better HRQoL related to anxiety/depression compared with both adolescents and adults (P < 0.05 for each comparison).

Figure 4.

Percentage of people with type 1 diabetes mellitus in Shantou, China, reporting no problem in categories of the EQ-5D17 health-related quality-of-life scale. People stratified according to age (children aged <13 years [n = 53; white bars]; adolescents aged 13–20 years [n = 80; black bars]; adults aged >20 years [n = 189; striped bars]). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; one way analysis of variance.

Multiple regression analysis found that individual diabetes education (P = 0.012), insulin injection regimen (P = 0.001) and HbA1c (P = 0.034) were independently associated with total SDSCA score. Household income (P = 0.040) and age (P = 0.005) were independently associated with EQ-5D index.

Discussion

The present study of diabetes self-care behaviours and HRQoL found that both foot care and self-monitoring of blood glucose were poor in people with T1DM in China. In addition, T1DM had an adverse impact on HRQoL, and the HRQoL of adults was significantly worse than that of children and adolescents.

It is known that people with T1DM who have suboptimal glycaemic control pay insufficient attention to diabetes self-care practices.19,20 A majority of participants in the present study (78.9%) reported having not examined their feet in the previous 7 days, despite this being the simplest to perform of the self-care activities. It is possible that participants may not have been aware of the need for foot care, due to the low rate of diabetes education in the study group (66.5% had received no diabetes education). In addition, cost is a substantial barrier to the use of blood glucose self-monitoring equipment in China.3 Few people with diabetes are able to afford such equipment, and their blood glucose levels must be monitored in hospital.

Diabetes had a significant impact on HRQoL. The proportion of participants in the present study who reported moderate or severe problems was significantly higher than in the general population of China.21 This result was consistent with most studies,8,9,14,22,23 but not all.24 Participants in the present study commonly reported problems with pain/discomfort, in accordance with the findings of others.25–27

Older people with T1DM have been shown to have poorer self-care behaviours than children with the condition, especially after leaving home and becoming focused on study or work.28–30 There were no significant differences between age groups in self-care behaviours in the present study, however, this is probably due to the small numbers of children and adolescents in this cohort.

Our finding that adults had significantly lower EQ-5D index than children and adolescents was consistent with other studies.31 This may be related to the presence of diabetic complications, since nephropathy has been shown to reduce HRQoL in people with T1DM.8 In addition, adults reported significantly worse anxiety/depression compared with younger people in the present study. Adults are generally independent in this society and experience burdens in factors including work, marriage, pregnancy or childrearing. Adolescents and adults with T1DM have been shown to have a higher rate of depression and lower self-esteem than children with the condition.6,32

Education is important in the self-care of people with T1DM.6 It is of interest that individual diabetes education had a substantial effect on total SDSCA score in the present study, but group education did not. It is possible that group education may generate resistance and could ignore what is most important to people with T1DM. In contrast, individualized diabetes education emphasizes the importance of increasing patient autonomy and independency, which help people with T1DM to discover and develop their inherent capacity to be responsible for themselves.33 Family behavioural interventions are known to be more effective than conventional education programmes in influencing self-care behaviours in adolescents with T1DM.34

The type of insulin injection regimen also had a major impact on self-care behaviours in the present study. People with an insulin pump or basal-bolus insulin regimen with four injections per day must self monitor glucose levels frequently and receive more diabetes education compared with other people with T1DM. Studies have indicated that both individual and group lifestyle interventions have positive effects on diet and self-care behaviours in people with diabetes, with group settings being most effective.35 Integrating education and other therapies, such as intensified insulin regimens, is an approach that is likely to achieve the most effective diabetes control.36

Self-care activity score was independently related to HbA1c level in the present study. Guidelines emphasize that effective self-care is an essential component of metabolic control.6 All self-care behaviours were equally important, but self-monitoring of blood glucose was most effective at influencing the individual’s HbA1c level in our study. Frequent and accurate blood glucose monitoring, and concomitant optimal adjustment of insulin to carbohydrate intake and exercise, are required to attain (and maintain) ideal glycaemic control.37,38 The frequency of self-monitoring is associated with improved HbA1c,39,40 but it was one of the least frequently performed self-care behaviours in the present study.

Income and age were independent predictors of HRQoL in the present study. Poor HRQoL causes suffering, can seriously interfere with daily diabetes self-management, and is associated with poor medical outcomes and high costs.41 Improvement in quality of care (determined by care practices that improve outcomes) will decrease the overall lifetime cost of diabetes and normalize life expectancy, by decreasing acute and chronic complications. More importantly, improving outcomes will improve HRQoL for both people with T1DM and their families. In people with T1DM in the USA, HRQoL was associated with a primary insurance source of Medicaid or another government-funded insurance scheme.42 We suggest that the Chinese government increases medical investment, subsidizes health insurance and reduces medical care costs as soon as possible, in order to improve HRQoL in people with T1DM.

This study is limited by the fact that participants were recruited using convenience sampling from six hospitals in Shantou, possibly affecting the generalizability of results. Further studies should include larger, more diverse populations.

In conclusion, the majority of people with T1DM in this region of China exhibit poor self-care behaviours and HRQoL. Self-care behaviours could be improved by enhancing individual diabetes education and implementing strict insulin regimens. Increasing the frequency of self-monitoring of blood glucose may improve metabolic control.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Helen McGuire (IDF Programmes & Policy, Brussels, Belgium), David Whiting (IDF Programmes & Policy, Brussels, Belgium), Katarzyna Kissimova-Skarbek (Department of Health Economics and Social Security, Jagiellonian University, Institute of Public Health, Krakow, Poland.) and JI Linong (Department of Endocrinology, Peking University People’s Hospital, Beijing, China) for their contributions to the 3C study. We also thank Sanofi Diabetes for their unrestricted grant for the 3C study.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was sponsored by Shantou University Medical College Clinical Research Enhancement Initiative.

References

- 1.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, et al. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 1047–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGuire H, Kissimova-Skarbek K, Whiting D, et al. The 3C study: coverage cost and care of type 1 diabetes in China-study design and implementation. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2011; 94: 307–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGuire H, Ji L. China’s 3C study-the people behind the numbers. Diabetes Voice 2012; 57: 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGuire H, Kissimova-Skarbek K and Whiting D. Coverage, cost and care of type 1 diabetes in Beijing and Shantou. ADA Abstract 2012; 6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.▪▪ ▪. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012; 35(1 suppl): S11–S63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.International Diabetes Federation. Global IDF/ISPAD Guideline for Diabetes in Childhood and Adolescence. International Diabetes Federation 2011.

- 7.Funnell MM, Brown TL, Childs BP, et al. National standards for diabetes self-management education. Diabetes Care 2012; 35(Suppl 1): S101–S108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahola AJ, Saraheimo M, Forsblom C, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with type 1 diabetes–association with diabetic complications (the FinnDiane study). Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010; 25: 1903–1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solli O, Stavem K, Kristiansen IS. Health-related quality of life in diabetes: the associations of complications with EQ-5D scores. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010; 8: 18–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Diabetes Association, Clarke W, Deeb LC, et al. Diabetes care in the school and day care setting. Diabetes Care 2013; 36(Suppl 1): S75–S79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toljamo M, Hentinen M. Adherence to self-care and glycaemic control among people with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Adv Nurs 2001; 34: 780–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Müller-Godeffroy E, Treichel S, Wagner VM, et al. Investigation of quality of life and family burden issues during insulin pump therapy in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus–a large-scale multicentre pilot study. Diabet Med 2009; 26: 493–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaser SS, Faulkner MS, Whittemore R, et al. Coping, self-management, and adaptation in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Ann Behav Med 2012; 43: 311–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hart HE, Redekop WK, Assink JH, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 1319–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yin Xu, Savage C, Toobert D, et al. Adaptation and testing of instruments to measure diabetes self-management in people with type 2 diabetes in mainland China. J Trnascult Nurs 2008; 19: 234–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Q, Hsia J, Yang G. Prevalence of smoking in China in 2010. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 2469–2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol group. Ann Med 2001; 33: 337–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsuchiya A, Ikeda S, Ikegami N, et al. Estimating an EQ-5D population value set: the case of Japan. Health Econ 2002; 11: 341–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang CW, Yeh CH, Lo FS, et al. Adherence behaviours in Taiwanese children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Nurs 2007; 16: 207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dashiff CJ, MeCaleb A, Cull V. Self-care of young adolescents with type l diabetes. J Pediatr Nurs 2006; 21: 222–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun S, Chen J, Johannesson M, et al. Population health status in China: EQ-5D results, by age, sex and socio-economic status, from the national health services survey 2008. Qual Life Res 2011; 20: 309–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faulkner MS. Quality of life for adolescents with type I diabetes: parental and youth perspectives. Pediatr Nurs 2003; 29: 362–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sparring V, Nystrom L, Wahlstrom R, et al. Diabetes duration and health-related quality of life in individuals with onset of diabetes in the age group 15–34 years – a Swedish population-based study using EQ-5D. BMC Public Health 2013; 13: 377–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laffel L, Connell A, Vangsness L, et al. General quality of life in youth with type 1 diabetes: relationship to patient management and diabetes-specific family conflict. Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 3067–3073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hart HE, Redekop WK, Bilo HJ, et al. Change in perceived health and functioning over time in patients with type I diabetes mellitus. Qual Life Res 2005; 14: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu AZ, Qiu Y, Radican L, et al. Marginal differences in health-related quality of life of diabetic patients with and without macrovascular comorbid conditions in the United States. Qual Life Res 2011; 20: 825–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hart HE, Bilo HJ, Redekop WK, et al. Quality of life of patients with type I diabetes mellitus. Qual Life Res 2003; 12: 1089–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaplin JE, Hanas R, Lind A, et al. Assessment of childhood diabetes-related quality-of-life in West Sweden. Acta Paediatr 2009; 98: 361–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanberger L, Ludvigsson J, Nordfeldt S. Health-related quality of life in intensively treated young patients with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes 2009; 10: 374–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalyva E, Malakonaki E, Eiser C, et al. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of children with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM): Self and parental perceptions. Pediatr Diabetes 2011; 12: 34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graue M, Wentzel-Larsen T, Hanestad BR, et al. Measuring self-reported, health-related, quality of life in adolescents with type 1 diabetes using both generic and disease-specific instruments. Acta Paediatr 2003; 92: 1190–1196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grey M, Davidson M, Boland E, et al. Clinical and psychosocial factors associated with achievement of treatment goals in adolescents with diabetes. J Adoles Health 2001; 28: 377–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Funnell M, Anderson R. Empowerment and self-management of diabetes. Clinical Diabetes 2004; 22: 123–127. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murphy HR, Wadham C, Rayman G, et al. Approaches to integrating paediatric diabetes care and structured education: experiences from the families, adolescents, and children’s teamwork study (FACTS). Diabet Med 2007; 24: 1261–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Norris SL, Lau J, Smith SJ, et al. Self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis on the effect on glycemic control. Diabetes Care 2002; 25: 1159–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Weerdt I, Visser AP, Kok GJ, et al. Randomized controlled multicentre evaluation of an education programme for insulin-treated diabetic patients: effects on metabolic control, quality of life, and costs of therapy. Diabet Med 1991; 8: 338–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anderson B, Ho J, Brackett J, et al. Parental involvement in diabetes management tasks: relationships to blood glucose monitoring adherence and metabolic control in young adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr 1997; 130: 257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haller MJ, Stalvey MS, Silverstein JH. Predictors of control of diabetes: monitoring may be the key. J Pediatr 2004; 144: 660–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schneider S, Iannotti RJ, Nansel TR, et al. Identification of distinct self-management styles of adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007; 30: 1107–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karter AJ, Ackerson LM, Darbinian JA, et al. Self-monitoring of blood glucose levels and glycemic control: the Northern California Kaiser Permanente diabetes registry. Am J Med 2001; 111: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Egede LE, Zheng P, Simpson K. Comorbid depression is associated with increased health care use and expenditures in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002; 25: 464–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naughton MJ, Ruggiero AM, Lawrence JM, et al. Health-related quality of life of children and adolescents with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus: SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2008; 162: 649–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]