Abstract

Objective

Routine fasting (12 h) is always applied before laparoscopic cholecystectomy, but prolonged preoperative fasting causes thirst, hunger, and irritability as well as dehydration, low blood glucose, insulin resistance and other adverse reactions. We assessed the safety and efficacy of a shortened preoperative fasting period in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Embase and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials up to 20 November 2015 and selected controlled trials with a shortened fasting time before laparoscopic cholecystectomy. We assessed the results by performing a meta-analysis using a variety of outcome measures and investigated the heterogeneity by subgroup analysis.

Results

Eleven trials were included. Forest plots showed that a shortened fasting time reduced the operative risk and patient discomfort. A shortened fasting time also reduced postoperative nausea and vomiting as well as operative vomiting. With respect to glucose metabolism, a shortened fasting time significantly reduced abnormalities in the ratio of insulin sensitivity. The C-reactive protein concentration was also reduced by a shortened fasting time.

Conclusions

A shortened preoperative fasting time increases patients’ postoperative comfort, improves insulin resistance, and reduces stress responses. This evidence supports the clinical application of a shortened fasting time before laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Keywords: Shortened preoperative fasting, complications, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, meta-analysis

Introduction

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, which is the treatment of choice for gallbladder stones and cholecystitis, is considered a safe procedure with a low risk of complications compared with traditional cholecystectomy. However, the rate of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) in the first 24 h after laparoscopic cholecystectomy ranges from 38% to 60% and affects the recovery of patients, leading to a prolonged hospital stay.1 Infection, adverse effects of anaesthesia, and carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum also affect patients’ recovery.2

Routine fasting (12 h) is always applied before elective surgery to reduce the gastric volume and acidity, which helps to avoid acute respiratory tract obstruction, aspiration pneumonia and Mendelson syndrome during anesthesia.3 Enhanced recovery after surgery protocols and new guidelines developed by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) recommend a 6-h preoperative fasting period to reduce operative-related complications. However, some studies have indicated that a long preoperative fasting period causes patient discomfort manifesting as thirst, hunger and irritability as well as adverse reactions such as dehydration, low blood glucose and insulin resistance. Oral administration of carbohydrates 2 h before anaesthesia for surgery is safe and reduces both insulin resistance and patient discomfort.4 Oral carbohydrates also reduce gluconeogenesis, glycogenolysis, lipolysis and muscle protein catabolism and increase glycogen reserves.5 At present, a shortened preoperative fasting period and administration of oral carbohydrates before laparoscopic cholecystectomy remain controversial. This systematic review was performed to provide reliable evidence for the application of this approach in clinical practice.

Three published meta-analyses included studies of paediatric, neoplastic and general surgery, but their results require further investigation. Recently, numerous trials evaluating the impact of preoperative fasting times in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy have yielded inconsistent results. Considering the differences in preoperative fasting times, we performed the present meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials to determine the impact of a shortened preoperative fasting period in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis of the effects of a shortened preoperative fasting time in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Materials and methods

Data sources, search strategies and study selection

We searched the PubMed and Embase databases and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials using the following core terms: “preoperative fasting,” “diet restriction,” “perioperative period,” and “clinical trial.” We applied no language restrictions and included all relevant articles up to 20 November 2015. We also conducted manual searches from the reference lists of identified trials. This study conforms to the PRISMA guidelines for the reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Two reviewers independently identified eligible reports. Discrepancies were resolved through group discussion. The eligibility criteria were as follows: treatment by laparoscopic cholecystectomy, randomized controlled design, and use of comparison groups in which one group underwent a shortened preoperative fasting time and the other (control group) underwent routine fasting or water as placebo. The exclusion criteria were as follows: the study did not evaluate the impact of the preoperative fasting time, patients included those who did not undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and data on some investigated outcomes were unavailable (e.g. under risk in operation, gastric volume, pain, PONV, glucose, insulin, insulin resistance/sensitivity, cortisol, C-reactive protein [CRP] and carnitine).

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors compiled the data using a predefined information sheet. The following items were extracted from the included articles: author, year, number of patients (experimental), diabetes, ASA level, fasting time in the experimental group, nutrient type, liquid volume, control type and conclusion. Two reviewers also independently assessed the risk of design bias in the included studies using the Cochrane Collaboration tool.9 The following outcomes were evaluated in this review: under risk in operation, gastric volume, pain, PONV, glucose, insulin, insulin resistance/sensitivity, cortisol, CRP and carnitine. These outcome measures were ranked according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation.10

Statistical analysis

We used the inverse variance method to pool continuous data and the Mantel–Haenszel method for dichotomous data; the results are presented as the standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence interval (CI), risk ratio (RR) with 95% CI (under risk in operation) and odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI. The I2 statistic was calculated to evaluate the extent of variability attributable to statistical heterogeneity between trials. In the absence of statistical heterogeneity (I2 < 50%), we used a fixed-effects model; otherwise we used a random-effects model.11 The median and quartile data were transformed to mean and SD for analysis.12 We analysed the following predefined subgroups to identify the sources of heterogeneity: nutritional types, control types and intake volume. We investigated publication bias by visually examining funnel plots and using the Begg–Mazumdar and Egger tests. The nonparametric “trim-and-fill” method was used to determine the stability if publication bias was present. Generally, a two-sided P-value of< 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analysis was performed with Review Manager (Version 5.3) and STATA (Version 12.0).

Results

Literature search and study characteristics

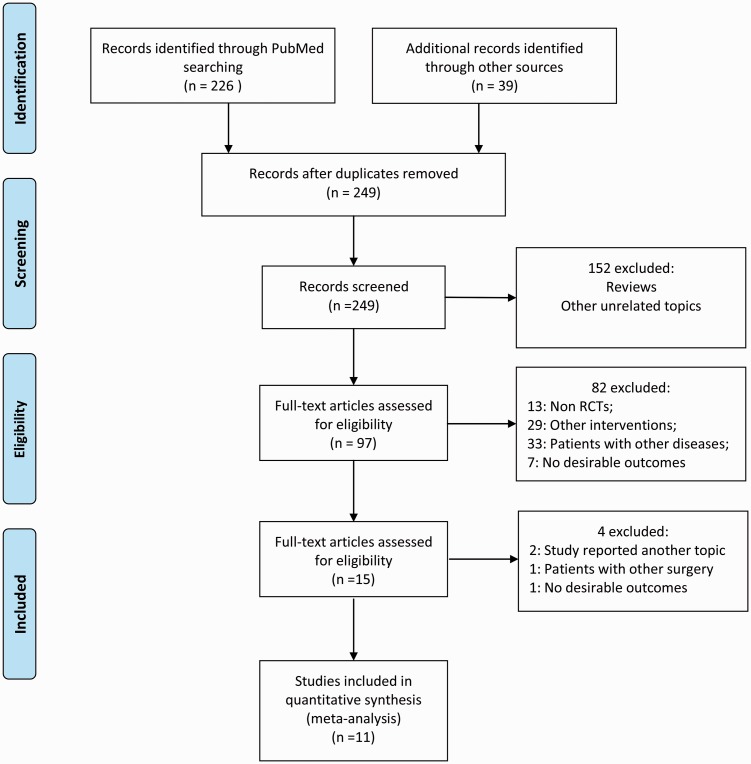

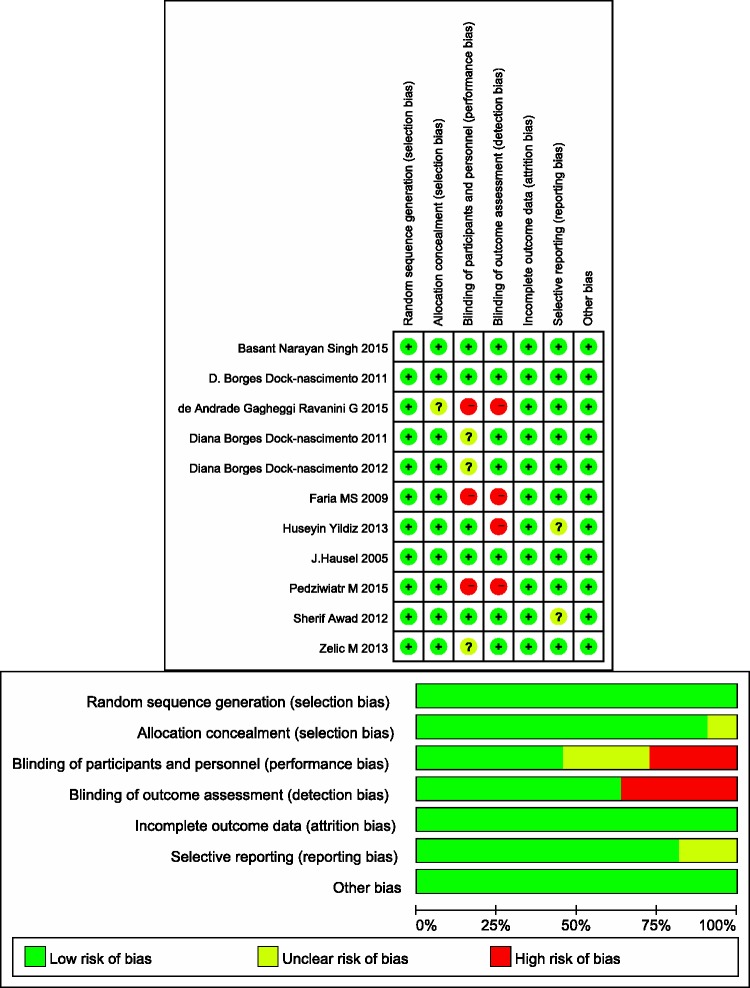

Our database search returned 249 articles after removing duplicates, from which we collected 11 trials for inclusion in our meta-analysis (Figure 1). All included patients underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The ASA class was not described in two articles, while one article included patients with an ASA class of 1 to 3. The preoperative fasting time was 2 h in all studies except one, in which the fasting time was 3 to 4 h. The intake type was carbohydrates (or maltodextrin) and carbohydrates plus protein, glutamine, antioxidants or other nutrients. The intake volume ranged from 200 to 400 ml. The control types were placebo control (water) and blank control (routine fasting). Blank control and placebo control were set parallel in three studies. With respect to the studies’ conclusions, one article did not recommend a shortened preoperative fasting period based on the results of glucose metabolism. Others considered a shortened fasting time to be safe, reduce patient discomfort, improve insulin sensitivity and reduce postoperative stress reactions (Table 1). Three studies did not use a blinding method, and four studies used inappropriate blinding methods or the assessor was not blinded to the study group. Overall, the included studies had high-quality designs (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included trials.

| Author | Year | No. of patients (Exp) | Inclusion | ASA | Fasting time (h) | Nutrient type | Intake volume (ml) | Control type | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pedziwiatr M5 | 2015 | 46 (22) | No-diabetes | 1–3 | 2 | Carbohydrate | 400 | Placebo | CHO-loading is not clinically justified in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. |

| de Andrade Gagheggi Ravanini G18 | 2015 | 38 (17) | No-diabetes | 1–2 | 2 | 33.5% Carbohydrate and 4% protein | 200 | Blank | Carbohydrate + protein–enriched solutions are safe, reduce insulin resistance, and do not increase the risk of bronchoaspiration. |

| Basant Narayan Singh1 | 2015 | 120 (40) | No-diabetes | ? | >2 | 12.5% Carbohydrate | 400 | Placebo/blank | Carbohydrate-rich drinks can minimize postoperative nausea, vomiting and pain without additional complications. |

| Zelic M19 | 2013 | 70 (35) | No-diabetes | 1–2 | 2 | 12.5% Carbohydrate | 400 | Blank | Preoperative feeding can reduce discomfort and decrease the perioperative stress response. |

| Huseyin Yildiz17 | 2013 | 60 (30) | No-diabetes | 1–2 | 2–3 | 12.5% Carbohydrate | 400 | Blank | Preoperative CHO reduces perioperative discomfort and improves perioperative well-being. |

| Diana Borges Dock-nascimento20 | 2012 | 36 (11;12) | No-diabetes | 1–2 | 2 | 12.5% Carbohydrate; 12.5% Carbohydrate + free glutamine | 200 | Blank | Preoperative feeding improves insulin sensitivity. |

| Sherif Awad21 | 2012 | 30 (15) | N/A | ? | 3–4 | Carbohydrate (50 g Carbohydrate + 15 g glutamine + antioxidants | 300 | Placebo | Carbohydrates prevent excessive/incomplete mitochondrial β-oxidation. |

| Diana Borges Dock-nascimento22 | 2011 | 48 (12) | No-diabetes | 1–2 | 2 | Maltodextrin + glutamine; Maltodextrin | 200 | Placebo | Carbohydrates improve insulin resistance and antioxidant defenses and decrease the inflammatory response. |

| D. Borges Dock-nascimento3 | 2011 | 56 (12;14) | No-diabetes | 1–2 | 2 | 12.5% Carbohydrate; 12.5% Carbohydrate + 10 g L-glutamine | 200 | Placebo/blank | Carbohydrate + L-glutamine is safe and does not increase the RGV during induction of anesthesia. |

| Faria MS23 | 2009 | 25 (12) | No-diabetes | 1–2 | 2 | 12.5% Maltodextrin | 200 | Blank | Carbohydrates diminish insulin resistance and the organic response to trauma. |

| J. Hausel24 | 2005 | 172 (55) | No-diabetes | 1–2 | 2 | 12.5% Carbohydrate | 400 | Placebo/blank | CHO may have a beneficial effect on postoperative nausea and vomiting 12–24 h after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. |

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; CHO, Carbohydrate; RGV

Figure 2.

Methodological quality of trials included in the meta-analysis. Risk-of-bias graph and summary.

Meta-analysis

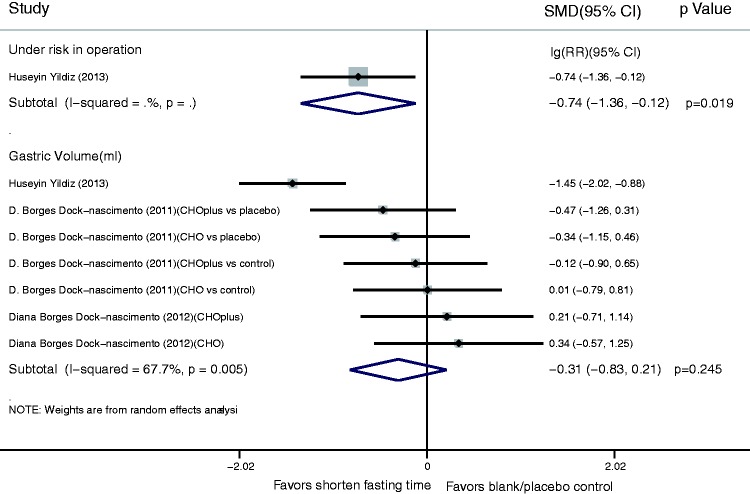

For the operative risk and gastric volume index, the fixed-effects model showed that a shortened fasting time reduced the operative risk (lg(RR), −0.74; 95% CI, −1.36 to −0.12; P = 0.019). There was no significant difference in the gastric volume between the shortened fasting and control groups (SMD, −0.31; 95% CI, −0.83 to 0.21) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Results of operative risk and gastric volume index in assessment of shortened fasting time. Forest plot showing that a shortened fasting time significantly reduced the operative risk (lg(risk ratio), −0.74; 95% confidence interval, −1.36 to −0.12; P = 0.019), but had no significant effect on gastric volume (standardized mean difference, −0.31; 95% confidence interval, −0.83 to 0.21).

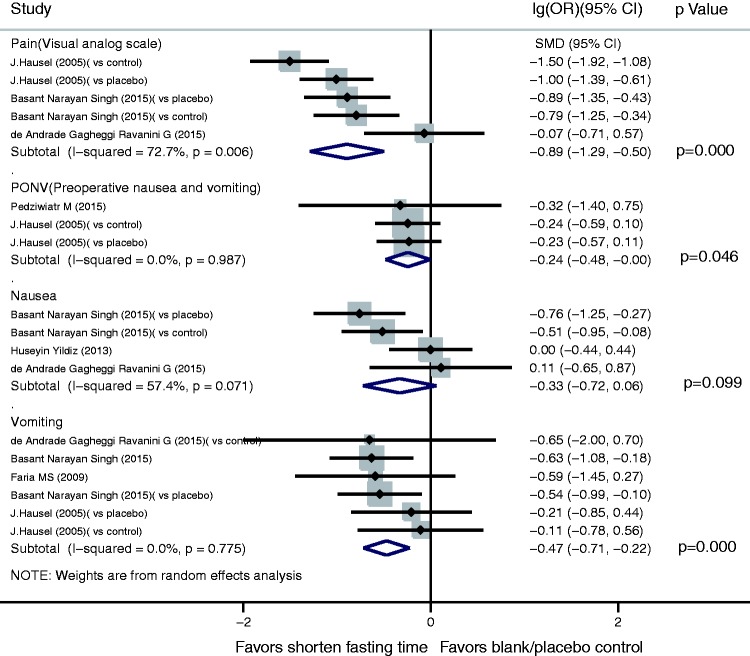

For the subjective sensation index, pain assessment using a visual analogue scale showed that a shortened fasting time significantly reduced postsurgical pain (SMD, −0.89; 95% CI, −1.29 to −0.50; P =0.000). A shortened fasting time also reduced both PONV (lg(OR), −0.24; 95% CI, −0.48 to −0.00; P = 0.046) and operative vomiting (lg(OR), −0.47; 95% CI, −0.71 to −0.22; P = 0.000). However, there was no significant difference in operative nausea between the shortened fasting and control groups (lg(OR), −0.33; 95% CI, −0.72 to 0.06) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Results of subjective sensation index in assessment of shortened fasting time. Forest plot showing that a shortened fasting time significantly reduced postoperative pain (standardized mean difference, −0.89; 95% confidence interval [CI], −1.29 to −0.50; P = 0.000), postoperative nausea and vomiting (lg(odds ratio [OR]), −0.24; 95% CI, −0.48 to −0.00; P = 0.046) and intraoperative vomiting (lg(OR), −0.47; 95% CI, −0.71 to −0.22; P = 0.000), but had no significant effect on intraoperative nausea (lg(OR), −0.33; 95% CI, −0.72 to 0.06).

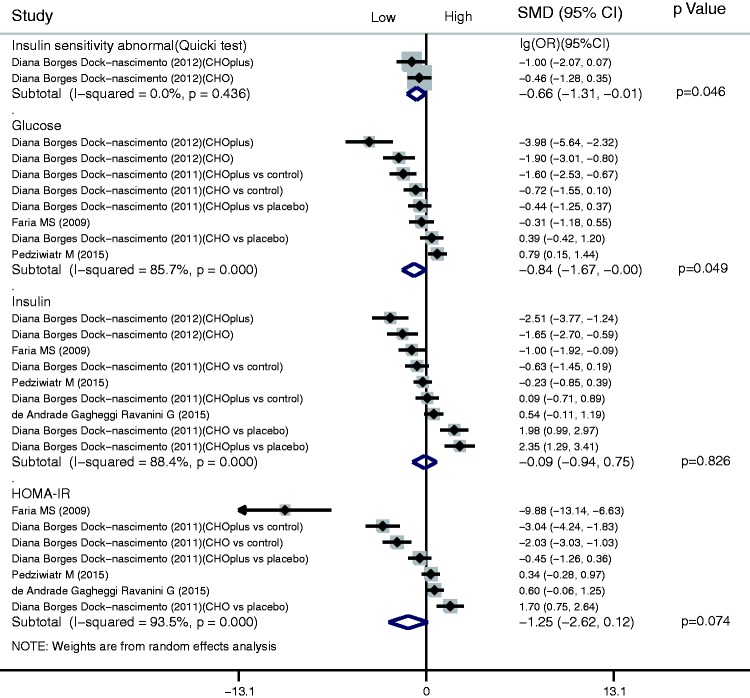

For the glucose metabolism index, a shortened fasting time significantly reduced abnormalities in the ratio of insulin sensitivity (lg(OR), −0.66; 95% CI, −1.31 to −0.01; P = 0.046). A shortened fasting time also significantly reduced the postsurgical glucose concentration (SMD, −0.84; 95% CI, −1.67 to −0.00; P = 0.049). There were no significant differences in either the insulin or homeostatic model assessment–insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) results between the shortened fasting and control groups (insulin: SMD, −0.09; 95% CI, −0.94 to 0.75 and HOMA-IR: SMD, −1.25; 95% CI, −2.62 to 0.12) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Results of glucose metabolism index in assessment of shortened fasting time. Forest plot showing that a shortened fasting time significantly reduced abnormalities in the ratio of insulin sensitivity (lg(odds ratio), −0.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], −1.31 to −0.01; P = 0.046) and reduced the postoperative glucose concentration (standardized mean difference [SMD], −0.84; 95% CI, −1.67 to −0.00; P = 0.049), but had no significant effects on the insulin concentration or homeostatic model assessment–insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) (insulin: SMD, −0.09; 95% CI, −0.94 to 0.75 and HOMA-IR: SMD, −1.25; 95% CI, −2.62 to 0.12).

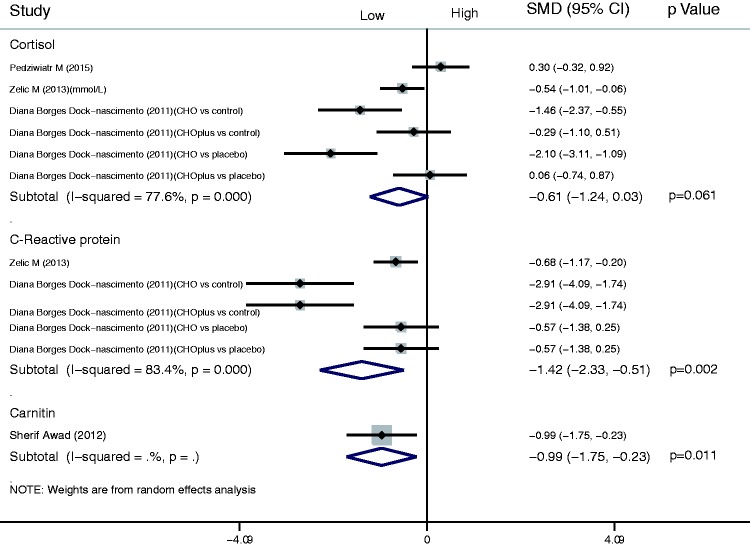

For the stress response index, there was no significant difference in the cortisol results between the shortened fasting and control groups (SMD, −0.61; 95% CI, −1.24 to 0.03). The results also indicated that a shortened fasting time reduced the concentrations of CRP (SMD, −1.42; 95% CI, −2.33 to −0.51; P = 0.002) and carnitine (SMD, −0.99; 95% CI, −1.75 to −0.23; P = 0.011) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Results of stress response index in assessment of shortened fasting time. Forest plot showing significant differences in the C-reactive protein and carnitine concentrations between the shortened fasting and control groups (standardized mean difference [SMD], −1.42; 95% confidence interval [CI], −2.33 to −0.51; P = 0.002 and SMD, −0.99; 95% CI, −1.75 to −0.23; P = 0.011, respectively).

Subgroup analysis

We used subgroup analysis to reduce significant heterogeneity among the results. Measurement of the intake volume before surgery reduced the heterogeneity among the gastric volume results, and adjusting for the control type reduced the heterogeneity of the nausea results (Table 2).

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis of the effect of a shortened fasting time in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

| Outcome | Subgroup | lg(OR)/SMD (95% CI) | P-value | Heterogeneity | P for heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | Overall | −0.892 (−1.287 to −0.497) | |||

| Nutritional types | |||||

| Carbohydrate | −1.055 (−1.365 to −0.745) | 0.000 | 52.00% | 0.100 | |

| Carbohydrate plus | −0.066 (−0.706 to 0.574) | 0.840 | .% | . | |

| Control types | |||||

| Blank control | −0.817 (−1.587 to −0.047) | 0.038 | 86.20% | 0.001 | |

| Placebo control | −0.956 (−1.254 to −0.658) | 0.000 | 0.00% | 0.709 | |

| Intake volume | |||||

| 200 ml liquid | −0.066 (−0.706 to 0.574) | 0.840 | .% | . | |

| 400 ml liquid | −1.055 (−1.365 to −0.745) | 0.000 | 52.00% | 0.100 | |

| Nausea | Overall | −0.329 (−0.720 to 0.061) | 0.099 | 57.40% | 0.089 |

| Nutritional types | |||||

| Carbohydrate | −0.417 (−0.850 to 0.016) | 0.059 | 63.30% | 0.065 | |

| Carbohydrate plus | 0.109 (−0.649 to 0.867) | 0.778 | .% | . | |

| Control types | |||||

| Blank control | −0.187 (−0.580 to 0.207) | 0.352 | 42.20% | 0.177 | |

| Placebo control | −0.758 (−1.247 to −0.269) | 0.002 | .% | . | |

| Intake volume | |||||

| 200 ml liquid | 0.109 (−0.649 to 0.867) | 0.778 | .% | . | |

| 400 ml liquid | −0.417 (−0.850 to 0.016) | 0.059 | 63.30% | 0.065 | |

| Glucose | Overall | −0.836 (−1.668 to −0.003) | 0.049 | 85.70% | 0.000 |

| Nutritional types | |||||

| Carbohydrate | −0.292 (−1.150 to 0.567) | 0.505 | 81.30% | 0.000 | |

| Carbohydrate plus | −1.859 (−3.533 to −0.185) | 0.030 | 86.40% | 0.001 | |

| Control types | |||||

| Blank control | −1.541 (−2.518 to −0.564) | 0.002 | 78.20% | 0.001 | |

| Placebo control | 0.277 (−0.441 to 0.995) | 0.449 | 63.40% | 0.065 | |

| Intake volume | |||||

| 200 ml liquid | −1.073 (−1.888 to −0.259) | 0.010 | 80.70% | 0.000 | |

| 400 ml liquid | 0.791 (0.146 to 1.436) | 0.016 | .% | . | |

| Insulin | Overall | −0.095 (−0.939 to 0.749) | 0.826 | 88.40% | 0.000 |

| Nutritional types | |||||

| Carbohydrate | −0.306 (−1.349 to 0.737) | 0.565 | 86.40% | 0.000 | |

| Carbohydrate plus | 0.160(−1.357 to 1.677) | 0.836 | 91.20% | 0.000 | |

| Control types | |||||

| Blank control | −0.774 (−1.617 to 0.069) | 0.072 | 81.70% | 0.000 | |

| Placebo control | 1.328 (−0.441 to 3.097) | 0.141 | 91.80% | 0.000 | |

| Intake volume | |||||

| 200 ml liquid | −0.081 (−1.084 to 0.923) | 0.875 | 89.70% | 0.000 | |

| 400 ml liquid | −0.231 (−0.853 to 0.391) | 0.466 | .% | . | |

| HOMA-IR | Overall | −1.249 (−2.621 to 0.123) | 0.074 | 93.50% | 0.000 |

| Nutritional types | |||||

| Carbohydrate | −1.839 (−4.272 to 0.594) | 0.138 | 95.40% | 0.000 | |

| Carbohydrate plus | −0.898 (−2.729 to 0.932) | 0.336 | 92.70% | 0.000 | |

| Control types | |||||

| Blank control | −3.126 (−5.811 to −0.440) | 0.023 | 95.50% | 0.000 | |

| Placebo control | 0.502 (−0.585 to 1.589) | 0.366 | 82.60% | 0.003 | |

| Intake volume | |||||

| 200 ml liquid | −1.666 (−3.403 to 0.072) | 0.060 | 94.40% | 0.000 | |

| 400 ml liquid | 0.341 (−0.284 to 0.965) | 0.285 | .% | . | |

| Cortisol | Overall | −0.607 (−1.241 to 0.027) | 0.061 | 77.60% | 0.000 |

| Nutritional types | |||||

| Carbohydrate | −0.876 (−1.795 to 0.044) | 0.062 | 85.00% | 0.000 | |

| Carbohydrate plus | −0.112 (−0.680 to 0.455) | 0.698 | 0.00% | 0.538 | |

| Control types | |||||

| Blank control | −0.699 (−1.282 to −0.115) | 0.019 | 50.40% | 0.133 | |

| Placebo control | −0.528 (−1.849 to 0.794) | 0.434 | 87.80% | 0.000 | |

| Intake volume | |||||

| 200 ml liquid | −0.911 (−1.869 to 0.048) | 0.063 | 79.10% | 0.002 | |

| 400 ml liquid | −0.143 (−0.961 to 0.676) | 0.732 | 77.10% | 0.037 | |

| CRP | Overall | −1.420 (−2.334 to −0.505) | 0.002 | 83.40% | 0.000 |

| Nutritional types | |||||

| Carbohydrate | −1.279 (−2.431 to −0.127) | 0.030 | 84.20% | 0.002 | |

| Carbohydrate plus | −1.699 (−3.996 to 0.598) | 0.147 | 90.30% | 0.001 | |

| Control types | |||||

| Blank control | −2.102 (−3.825 to −0.379) | 0.017 | 90.30% | 0.000 | |

| Placebo control | −0.566 (−1.144 to 0.012) | 0.055 | 0.00% | 1.000 | |

| Intake volume | |||||

| 200 ml liquid | −1.331 (−1.805 to −0.856) | 0.000 | 85.50% | 0.000 | |

| 400 ml liquid | −0.683 (−1.165 to −0.200) | 0.006 | .% | . |

OR, odds ratio; SMD, standardized mean difference; CI, confidence interval; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment–insulin resistance

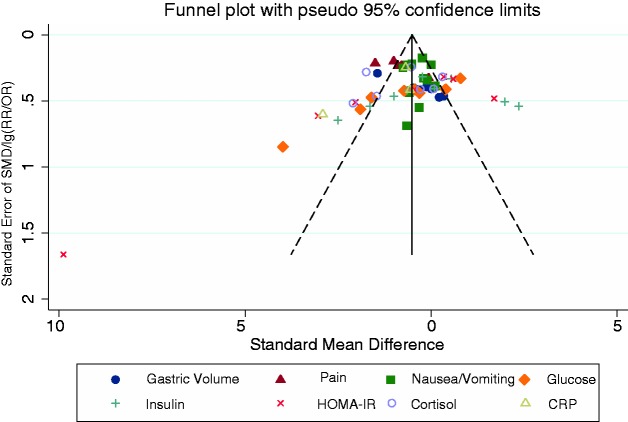

Publication bias

The Begg and Egger tests provided no evidence of significant publication bias in most outcome assessments except the gastric volume (Egger test, P = 0.000; Begg test, N.S.), glucose (Egger test, P = 0.001; Begg test, P = 0.004) and HOMA-IR (Egger test, P = 0.035; Begg test, N.S.) (Figure 7). The nonparametric “trim-and-fill” method was used to determine the reliability of our results; it showed no qualitative alterations except that a shortened fasting time reduced the gastric volume (random-effects model: SMD, −0.697; 95% CI, −1.207 to −0.187; asymptotic P = 0.007).

Figure 7.

Funnel plots of publication bias. Begg and Egger tests provided no evidence of significant publication bias in most outcome assessments except gastric volume (Egger test, P = 0.000; Begg test, P = N.S.), glucose (Egger test, P = 0.001; Begg test, P = 0.004) and homeostatic model assessment–insulin resistance (Egger test, P = 0.035; Begg test, P = N.S.).

Discussion

In total, 11 articles and 701 patients were included in this systematic review of a variety of outcome measures. The data demonstrate that there is an overall benefit associated with a shortened preoperative fasting time, especially in terms of the subjective sensation index.

In 2009, Brady et al.6 published a study on the effect of preoperative fasting on perioperative complications in children. Their study showed that 120 minutes of preoperative fasting did not lead to a higher gastric volume and lower gastric pH, but reduced perioperative discomfort. In 2015, Pinto Ados et al.7 published a meta-analysis of the impact of a shortened fasting time on perioperative complications in patients undergoing elective cancer surgery. The effects of preoperative carbohydrates on glycaemic parameters, inflammatory markers, indicators of malnutrition and the hospital stay were evaluated in patients who underwent surgery for colorectal cancer and gastric cancer. However, because their analysis included only a small number of clinical studies, the evidence was unreliable. A meta-analysis of shortened preoperative fasting times published in 2014 included elective abdominal surgery, orthopaedic surgery, cardiac surgery and thyroidectomy and assessed the length of hospital stay, passage of flatus, glucose metabolism and postoperative complications. However, the design risk of the included studies was relatively high and included variety.8 Studies of laparoscopic cholecystectomy were included in this study. This procedure is associated with low levels of trauma and is very common in general surgery. This type of surgical research could lead to promotion of a shortened fasting time in the clinical setting.

The present meta-analysis indicates that oral carbohydrates taken 2 hours before surgery do not affect the gastric volume. One report even concluded that carbohydrates can reduce the gastric volume to a greater extent than can routine fasting. Okabe et al.21 indicated that clear fluids, orange juice, and non-human milk had no significant effect on gastric emptying, although the total calories were the main influencing factor.13 Oral carbohydrates significantly reduced postoperative pain, nausea and vomiting; one clinical trial of adenotonsillectomy had similar findings, although the results were not statistically significant.14 Postoperative insulin resistance refers to the reduction in tissue sensitivity and reactivity after surgery. HOMA-IR, calculated according to the formula blood glucose concentration (mg/dl) × blood insulin concentration (μU/ml)/405, can be used to evaluate the level of insulin resistance. Abnormal glucose tolerance and insulin resistance lead to poor recovery after surgery. Our analysis showed that oral carbohydrates reduce insulin resistance and enhance sensitivity. One study showed that carbohydrates also reduce insulin resistance in patients undergoing maxillofacial surgery.15 A certain stress response occurs after any type of surgery. Cortisol, which is regulated by adrenocorticotrophic hormone and increases after surgery, plays an important role in the immune system. CRP is another inflammatory indicator that significantly increases in the first 24 to 48 hours after surgery. The results of the present study indicate that oral carbohydrates lower cortisol concentrations, although the effect is not statistically significant. Furthermore, oral carbohydrates significantly reduce the CRP concentration. A study involving gastrointestinal surgery showed that oral carbohydrates taken 2 hours before surgery significantly reduced the postoperative inflammatory response and CRP/albumin ratio and shortened the hospital stay.16 Volume intake was a source of heterogeneity. There were no significant differences between the 200-ml carbohydrate intake group and the control group, while the gastric volume was reduced in the 400-ml intake group. After the publication bias was eliminated using the “trim-and-fill” method, a shortened fasting time and carbohydrate intake were found to reduce the gastric volume, which is consistent with the findings of another clinical trial.17 The control type may be a source of heterogeneity in postoperative nausea. A shortened fasting time and carbohydrate intake significantly reduced nausea when the control type was placebo (water).

Although the outcome measures of a shortened preoperative fasting time for laparoscopic cholecystectomy were comprehensively evaluated, this study had several limitations. First, we did not have specific individual data for all of the trials; thus, our statistical analysis could only be performed at the study level. Second, although subgroup analysis was performed, there was heterogeneity in several outcomes. This indicates that there are still unknown factors that cause heterogeneity. Third, the gastric volume, glucose concentration, and HOMA-IR were likely sources of publication bias.

Conclusions

The findings of our study suggest that the preoperative fasting time is associated with increased postoperative comfort, improved insulin resistance, and a reduced stress response in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This evidence supports the clinical application of a shortened fasting time in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics

Not applicable. The study was a systematic review and meta-analysis of published data.

References

- 1.Singh BN, Dahiya D, Bagaria D, et al. Effects of preoperative carbohydrates drinks on immediate postoperative outcome after day care laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 2015; 29: 3267–3272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sárkány P, Lengyel S, Nemes R, et al. Non-invasive pulse wave analysis for monitoring the cardiovascular effects of CO2 pneumoperitoneum during laparoscopic cholecystectomy–a prospective case-series study. BMC Anesthesiol 2014; 14: 98–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borges Dock-Nascimento D, Aguilar-Nascimento JE, Caporossi C, et al. Safety of oral glutamine in the abbreviation of preoperative fasting: a double-blind, controlled, randomized clinical trial. Nutr Hosp 2011; 26: 86–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yilmaz N, Cekmen N, Bilgin F, et al. Preoperative carbohydrate nutrition reduces postoperative nausea and vomiting compared to preoperative fasting. J Res Med Sci 2013; 18: 827–832. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pędziwiatr M, Pisarska M, Matłok M, et al. Randomized clinical trial to compare the effects of preoperative oral carbohydrate loading versus placebo on insulin resistance and cortisol level after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Pol Przegl Chir 2015; 87: 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brady M, Kinn S, Ness V, et al. Preoperative fasting for preventing perioperative complications in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009, pp. CD005285–CD005285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinto Ados S, Grigoletti SS, Marcadenti A. Fasting abbreviation among patients submitted to oncologic surgery: systematic review. Arq Bras Cir Dig 2015; 28: 70–73. [in Portuguese, English Abstract]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith MD, McCall J, Plank L, et al. Preoperative carbohydrate treatment for enhancing recovery after elective surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014, pp. CD009161–CD009161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins J and Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0. Cochrane Handbook, 2011.

- 10.Davoli M, Amato L, Clark N, et al. The role of Cochrane reviews in informing international guidelines: a case study of using the grading of recommendations, assessment, development and evaluation system to develop world health organization guidelines for the psychosocially assisted pharmacological treatment of opioid dependence. Addiction 2015; 110: 891–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo J, Yang J, Li Y. Association of hOGG1 Ser326Cys polymorphism with susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015; 8: 8977–8985. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005; 5: 13–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Andrade Gagheggi Ravanini G, Portari Filho PE, Abrantes Luna R, et al. Organic inflammatory response to reduced preoperative fasting time, with a carbohydrate and protein enriched solution; a randomized trial. Nutr Hosp 2015; 32: 953–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zelić M, Štimac D, Mendrila D, et al. Preoperative oral feeding reduces stress response after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Hepatogastroenterology 2013; 60: 1602–1606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yildiz H, Gunal SE, Yilmaz G, et al. Oral carbohydrate supplementation reduces preoperative discomfort in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Invest Surg 2013; 26: 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dock-Nascimento DB, Aguilar-Nascimento JE, Linetzky Waitzberg D. Ingestion of glutamine and maltodextrin two hours preoperatively improves insulin sensitivity after surgery: a randomized, double blind, controlled trial. Rev Col Bras Cir 2012; 39: 449–455. [in Portuguese, English Abstract]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Awad S, Stephens F, Shannon C, et al. Perioperative perturbations in carnitine metabolism are attenuated by preoperative carbohydrate treatment: another mechanism by which preoperative feeding may attenuate development of postoperative insulin resistance. Clin Nutr 2012; 31: 717–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dock-Nascimento DB, de Aguilar-Nascimento JE, Magalhaes Faria MS, et al. Evaluation of the effects of a preoperative 2-hour fast with maltodextrine and glutamine on insulin resistance, acute-phase response, nitrogen balance, and serum glutathione after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a controlled randomized trial. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2012; 36: 43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faria MS, de Aguilar-Nascimento JE, Pimenta OS, et al. Preoperative fasting of 2 hours minimizes insulin resistance and organic response to trauma after video-cholecystectomy: a randomized, controlled, clinical trial. World J Surg 2009; 33: 1158–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hausel J, Nygren J, Thorell A, et al. Randomized clinical trial of the effects of oral preoperative carbohydrates on postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 2005; 92: 415–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okabe T, Terashima H, Sakamoto A. Determinants of liquid gastric emptying: comparisons between milk and isocalorically adjusted clear fluids. Br J Anaesth 2015; 114: 77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jabbari Moghaddam Y, Seyedhejazi M, Naderpour M, et al. Is fasting duration important in post adenotonsillectomy feeding time? Anesth Pain Med 2014; 4: e10256–e10256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh M, Chaudhary M, Vashistha A, et al. Evaluation of effects of a preoperative 2-hour fast with glutamine and carbohydrate rich drink on insulin resistance in maxillofacial surgery. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res 2015; 5: 34–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pexe-Machado PA, de Oliveira BD, Dock-Nascimento DB, et al. Shrinking preoperative fast time with maltodextrin and protein hydrolysate in gastrointestinal resections due to cancer. Nutrition 2013; 29: 1054–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]