Abstract

Objectives

A double-blind randomised study to evaluate the opioid sparing effect and safety of nefopam when administered via intravenous patient controlled analgesia (PCA) with fentanyl.

Methods

Patients planned for elective open laparotomy, were randomly assigned to receive into fentanyl 25 µg/ml (SF group) or nefopam 2.4 mg/ml plus fentanyl 25 µg/ml (NF group). Patients were assessed before surgery and for 24 h postoperatively.

Results

Total PCA fentanyl consumption was significantly lower in the NF group (n = 35) than the SF group (n = 36). Pain scores were significantly lower and patients’ satisfaction with treatment significantly better in the NF group than the SF group. Dry mouth and dizziness were significantly more frequent in the NF group than the SF group. There were no other statistically significant between-group differences in the incidence of adverse events.

Conclusions

Intravenous PCA using nefopam + fentanyl following laparotomy has an opioid sparing effect and is associated with a low incidence of some of the typical opioid related adverse events.

Trial registry

Clinicaltrials.gov Registration No: NCT02596269

Keywords: Adverse events, nefopam, fentanyl; opioid sparing, patient controlled analgesia, laparotomy

Introduction

Approximately 80% of patients undergoing surgery may experience pain and for 86% of these patients the pain will be moderate-to-severe in its intensity.1 Postoperative hyperalgesia after major surgery not only increases morbidity and mortality but can also initiate the development of chronic postoperative pain.2,3 Opioid based patient controlled analgesia (PCA) has been commonly adopted to manage postoperative pain, and analgesics of different classes with different mechanisms of action are often combined to reduce the dose of each medicine and so lessen the likelihood of adverse events.4 Adjuvant treatment with agents such as nefopam, paracetamol, non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and ketamine have been shown in many studies to enhance postoperative analgesia or reduce opioid related side effects after some major surgeries. 4–8

Nefopam hydrochloride (Acupan®, BIOCODEX, France) is a centrally acting antinociceptive compound that inhibits the reuptake of serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine, the three most important substances in the transmission of pain, and has supraspinal and spinal sites of action.9 Studies in animals have also shown that spinal noradrenergic modulation and blockade of voltage sensitive calcium and sodium channels by nefopam modulates glutamatergic transmission.10,11 As a consequence, there is decreased activation of postsynaptic glutamatergic receptors (e.g. N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors), which are involved in the development of hyperalgesia.10,11

Nefopam was developed in the early 1970s as an antidepressant and myorelaxant,12 but has been shown to be effective in preventing acute postsurgical hyperalgesia13–15 and nonsurgical neuropathic pain.16 Oral and intravenous forms of nefopam are used, and the drug has an oral bioavailability of 40% and a plasma half-life of 3-5 h. Plasma peak concentrations are reached 15-20 min after intravenous injection and at 30 min during continuous infusion.17 Although the minimal effective concentration of nefopam is not known, its usual daily dose for postoperative pain ranges from 20 – 120 mg intravenously and 90 – 180 mg orally;14 there may be a ceiling effect at approximately 90 mg/day.18

The effect of nefopam in the prevention of postoperative pain has been reviewed,19 and a large number of clinical studies have explored the use of nefopam in various perioperative settings.1,6,8,13-16,18-24 However, its use as an adjunctive or main agent for postoperative intravenous PCA has only been evaluated in limited patient groups, 20-22 and to our knowledge, has not been evaluated after laparotomy.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the opioid sparing effect of nefopam when administered intravenously with fentanyl as PCA, and to evaluate any adverse events (AEs) that occurred over a 24 h period following surgery in patients who had undergone laparotomy.

Patients and methods

Study population

The study recruited patients aged 20 – 65 years and classified as American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I–II,25 who were scheduled for elective open laparotomy under general anaesthesia at Seoul National University Hospital, Republic of Korea between October 2012 and September 2013. Exclusion criteria were: the presence of renal or hepatic disease; high risk of urinary retention; seizure history; known allergy to any of the medications used; current history of psychiatric disorder, or taking psychotropic medications or monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Patients who could not understand the verbal rating scale (VRS) and/or the 11-point numeric rating scale (NRS)26 were also excluded.

Ethical approval for the study (IRB No. 1203-082-402) was provided by the Institutional Review Boards in Seoul National University Hospital on 1 October 2012. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Study design

The study was double blind and patients were assessed pre- and postsurgery for 24 h. Patients were randomly allocated between two treatment groups using a computer generated code. Both groups were provided with 50 ml of intravenous PCA: SF group, 1250 µg fentanyl in normal saline (25 µg/ml); NF group 1250 µg fentanyl plus 120 mg nefopam in normal saline (25 µg/ml fentanyl and 2.4 mg/ml nefopam). The dose of nefopam was based on its maximum recommended daily dose. The randomization codes were kept by an independent anaesthetist and were only opened after study completion or in the case of an emergency.

On the day before surgery, pain intensity was evaluated using the VRS (0, no pain; 1, mild pain; 2, moderate pain; 3, intense pain) and NRS (numbers from 0 to 10 representing ‘no pain’ to ‘worst pain imaginable’), and were shown how to use the PCA device. On the day of surgery, electrocardiography, noninvasive blood pressure (BP), peripheral oxygen saturation and end tidal carbon dioxide monitors were attached to each patient for continuous monitoring. Anaesthesia was induced with 30 mg lidocaine and 2 mg/kg propofol iv, followed by 0.9 mg/kg rocuronium for facilitation of tracheal intubation. Anaesthesia was maintained with 2.0–2.5% sevoflurane and 50% air in oxygen. A PCA device (APM®, Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL) was connected to the intravenous line but remained turned off while the patient was in the postanaesthesia care unit (PACU). For both treatment groups, the intravenous PCA was provided without a background of continuous infusion and with limits of 1 ml bolus, 8 min lockout time (maximum of 7.5 ml/h and 180 ml/day). The intravenous PCA was refilled if required and was available throughout the 24 h study period.

An anaesthetist not involved in the study assessed pain intensity using the VRS score at 5 min intervals as soon as the patient awoke. If the patient reported VRS ≥ 3, the anaesthetist administered a rescue bolus dose of 1 µg/kg fentanyl iv. Additional rescue bolus doses of fentanyl were administered until VRS < 3. The patient was withdrawn from the study if the score did not fall below 3 despite five rescue doses of fentanyl and after 30 min in PACU. For those patients with VRS < 3, the PCA device was turned on and the patient was encouraged to use the preset bolus doses of study treatments. After 30 min in PACU, patients were transferred to a ward and a research fellow anaesthetist not involved in the study recorded NRS pain score at rest and on moving at 1 h, 2 h, 6 h, 12 h and 24 h postsurgery. Data on the cumulative PCA dose as displayed on the PCA device were recorded and transferred to a computer for interpretation. No additional analgesics, antipyretics, or anti-inflammatory drugs were permitted during the study.

Sedation was assessed by the independent research fellow anaesthetist using the Observer’s Assessment of Alertness and Sedation (OAA/S) scale (5, responds readily to name spoken in normal tone; 4, lethargic response to name spoken in normal tone; 3, responds only after name is called loudly or repeatedly; 2, responds only after mild prodding or shaking; 1, does not respond to mild prodding or shaking; 0, does not respond to noxious stimulus).27 Patients were considered sedated if the OAA/S scale score was < 4 at any one time point during the PACU stay, and < 5 on the ward.

Any AEs observed during the 24-h study period were recorded by the independent research fellow anaesthetist. Patients were asked if they had experienced any of the following: hypertension; tachycardia; sweating, shivering; nausea; vomiting; sedation; pruritus; dry mouth. Hypertension and tachycardia were also defined as BP or heart rate (HR) changes of ≥ 20% from preoperative baseline values on more than two consecutive evaluation points. Patients who experienced nausea and vomiting received 0.075 mg palonosetron iv. In spite of satisfactory pain control, if the patient persistently complained of any of the above adverse events, PCA was stopped and the patient was withdrawn from the study. Patients were also withdrawn from the study if, on the OAA/S scale, they scored zero at any time point or 1 at more than two consecutive time points. Additionally, a systolic BP > 160 mmHg, a diastolic BP > 100 mmHg, or HR > 100 beats/min at two consecutive time points or intolerable palpitations were also criteria for withdrawal.

Satisfaction of the analgesia achieved with intravenous PCA was assessed at the end of the study (24 h after surgery) using a 4-point VRS (0, no satisfaction; 1, mild satisfaction; 2, moderate satisfaction; 3, intense satisfaction).

Statistical analyses

The primary study endpoint was the cumulative dose of fentanyl administered via PCA. Secondary endpoints were the comparison of pain intensity and occurrence of AEs.

Based on previous data,1 32 subjects per group were required to detect a 20% reduction in fentanyl requirements in the first 24 h after surgery, with an alpha level of 0.5 (two-tailed) and a beta level of 0.1 (90% power). Therefore, estimating a dropout rate of 20%, 36 patients were required for each group. Patient characteristics, intraoperative data, cumulative fentanyl consumption, mean BP and HR, were analysed using Student’s t-test. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to adjust for baseline differences between the two groups. The incidence of AEs and patient satisfaction were analysed using χ2 test. Pain and sedation scores were analysed using Mann–Whitney U-test.

P-values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant, and statistical analyses were performed using SPSS® version 19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows®.

Results

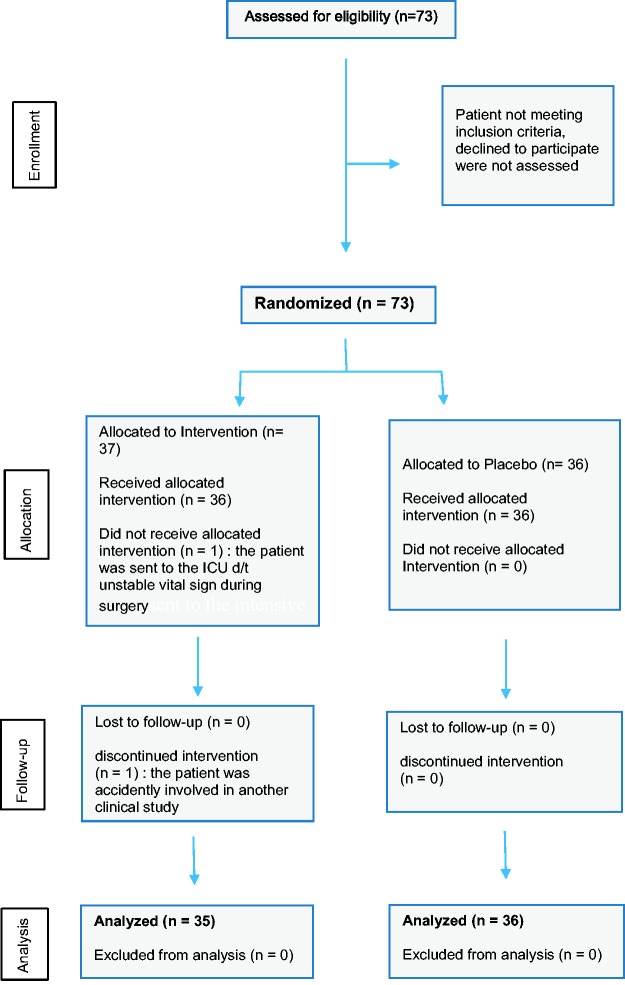

The study recruited 73 patients (NF group n = 37, SF group n = 36) (Figure 1); two of which were withdrawn from the NF group (one had unstable vital signs and the other was accidently enrolled into another study). Demographic, surgical and fentanyl consumption data for the remaining 71 patients are shown in Table 1. With the exception of the ratio of males to females and height of the patients, there were no statistically significant between-group differences in baseline characteristics, surgical data, or rescue fentanyl consumption during PACU stay. Patients in the NF group consumed significantly less fentanyl on the ward (from 30 min – 24 h postsurgery; PCA consumption) than those in the SF group (P = 0.001; Table 1). The total amount of fentanyl consumed in the first 24 h after surgery was significantly lower in the NF group than the SF group (P = 0.0009; Table 1). When ANCOVA was used to adjust for baseline differences in sex and height, PCA fentanyl consumption and total fentanyl consumption remained significantly lower in the NF group than the SF group (P = 0.005 and P = 0.004, respectively).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing progress through the phases of the randomised double blind study comparing the efficacy and safety of intravenous nefopam/fentanyl versus fentanyl alone as postoperative patient controlled analgesia following laparotomy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients receiving patient controlled analgesia (PCA) with nefopam + fentanyl (NF group) or fentanyl alone (SF group) following laparotomy.

| Characteristic | NF group n = 35 | SF group n = 36 | Statistical significancea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, male/female | 14/21 (40/60) | 23/13 (64/36) | P = 0.044 |

| Age, years | 56 ± 7 | 55 ± 8 | NS |

| Height, cm | 160 ± 9 | 164 ± 8 | P = 0.022 |

| Weight, kg | 62 ± 11 | 66 ± 8 | NS |

| Underlying disease, yes/no | 18/17 (51/49) | 19/17 (53/47) | NS |

| Surgery time, min | 102 ± 64 | 104 ± 61 | NS |

| Anaesthesia time, min | 139 ± 69 | 144 ± 65 | NS |

| Rescue fentanyl consumption, µg | 37.1 ± 42.9 | 44.2 ± 39.4 | NS |

| PCA fentanyl consumption, µg | 496.4 ± 287.0 | 767.4 ± 370.1 | P = 0.001 |

| Total 24-h fentanyl consumption, µg | 533.5 ± 288.0 | 811.6 ± 377.6 | P = 0.0009 |

Data presented as mean ± SD or n (%)

Student’s t-test.

NS, not statistically significant (P ≥ 0.05); PACU, postanaesthetic care unit.

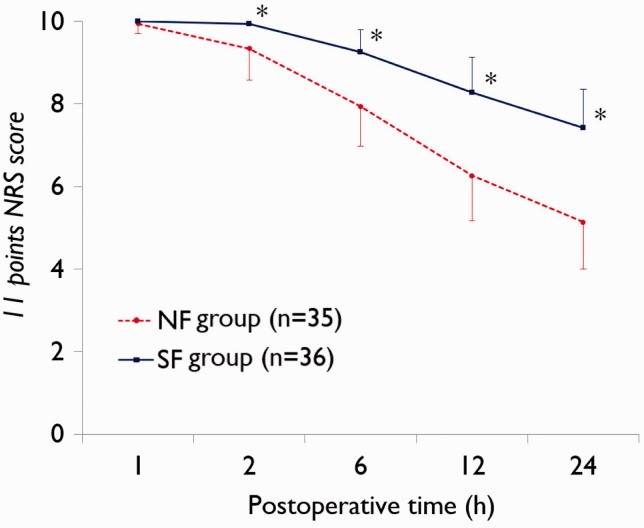

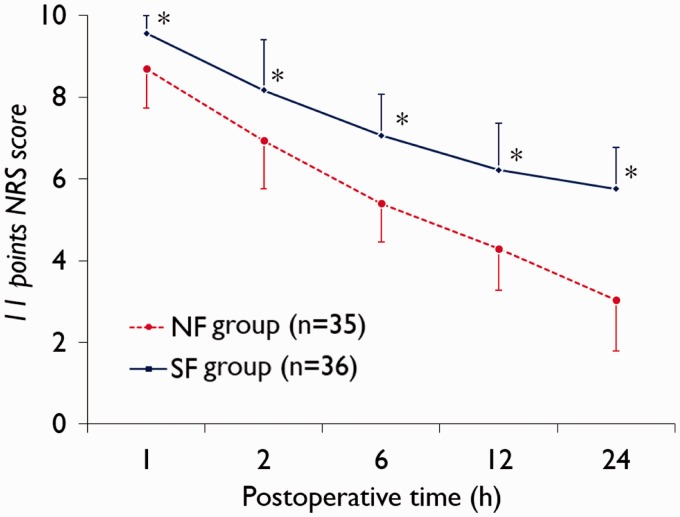

Data regarding NRS scores are shown in Figures 2 and 3. Patients in the NF group had significantly lower NFS scores on movement from 2 h postsurgery (P < 0.0001 at each timepoint; Figure 2) and at rest from 1 h postsurgery (P < 0.0001 at each timepoint; Figure 3) compared with the SF group.

Figure 2.

Postoperative pain score (11-point numerical rating scale [NRS]26) on movement in patients receiving patient controlled analgesia (PCA) with nefopam + fentanyl (NF group) or fentanyl alone (SF group) following laparotomy. *P < 0.0001; Mann–Whitney U-test.

Figure 3.

Postoperative pain score (11-point numerical rating scale [NRS]26) at rest in patients receiving patient controlled analgesia (PCA) with nefopam + fentanyl (NF group) or fentanyl alone (SF group) following laparotomy. *P < 0.0001; Mann–Whitney U-test.

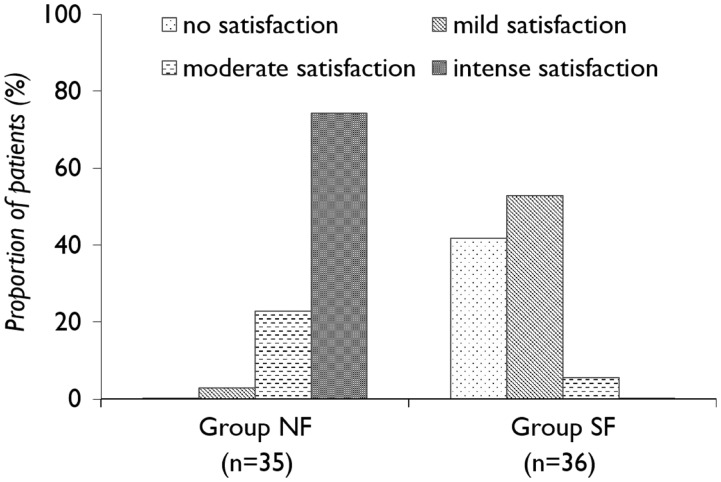

Patient satisfaction data are shown in Figure 4. There was a significant between-group difference in proportions; with significantly more patients reporting moderate or intense streatment satisfaction in the NF group than the SF group (P < 0.0001).

Figure 4.

Treatment satisfaction at 24 h postsurgery in patients receiving patient controlled analgesia (PCA) with nefopam + fentanyl (NF group) or fentanyl alone (SF group) following laparotomy. There is a significant between-group difference in proportions (P < 0.0001; χ2-test).

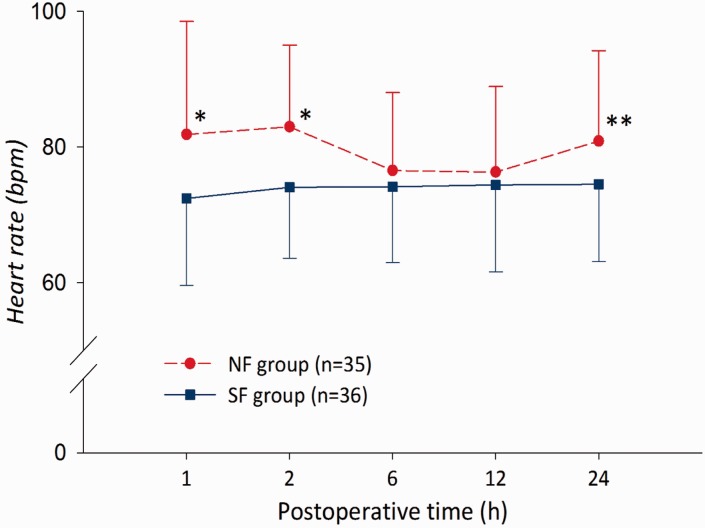

Data regarding AEs experienced during the study are shown in Table 2. Dry mouth and dizziness were significantly more frequent in the NF group than the SF group (P = 0.02 and P = 0.048, respectively). There were no other statistically significant between-group differences in the incidence of AEs. A total of two patients in the NF and one in the SF group experienced moderate-to-severe sweating. Tachycardia was experienced by two patients in the NF group. Mean HR was significantly higher in the NF group than the SF group at 1, 2 and 24 h postsurgery (P = 0.010, P = 0.001 and P = 0.034, respectively; Figure 5).

Table 2.

Adverse events during the initial 24 h following laparotomy in patients receiving patient controlled analgesia (PCA) with nefopam + fentanyl (NF group) or fentanyl alone (SF group).

| Adverse event | NF group n = 35 | SF group n = 36 | Statistical significancea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertensionb | 3 (8) | 2 (6) | NS |

| Tachycardiab | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | NS |

| Nausea | 8 (22) | 4 (11) | NS |

| Vomiting | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | NS |

| Sedationc | 30 (83) | 23 (66) | NS |

| Dizziness | 11 (31) | 4 (11) | P = 0.048 |

| Sweating | 5 (14) | 3 (9) | NS |

| Shivering | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | NS |

| Itching | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA |

| Dry mouth | 32 (89) | 23 (66) | P = 0.020 |

Data presented as n of patients (%).

χ2-test.

Hypertension and tachycardia were defined as BP or heart rate (HR) changes of ≥ 20% from preoperative baseline values on more than two consecutive evaluation points.

Observer’s Assessment of Alertness and Sedation (OAA/S) scale score < 4 at any one time point during postanaesthetic care unit stay or < 5 on the ward.

NS, not statistically significant (P ≥ 0.05); NA, not available.

Figure 5.

Postoperative heart rate in patients receiving patient controlled analgesia (PCA) with nefopam + fentanyl (NF group) or fentanyl alone (SF group) following laparotomy. *P < 0.01,**P < 0.05; Student’s t-test.

Discussion

Patients in the NF group consumed significantly less PCA fentanyl for postoperative pain control than those in the NF group in the present study. This was associated with decreased intensity of pain both at rest and on moving, and increased patient satisfaction at 24-h postsurgery in the NF group compared with the SF group, findings that are in agreement with those of others.1,6,8,15,19,23 A systematic review of nefopam studies concluded that nefopam has a postoperative morphine sparing effect of almost 30% and decreases pain intensity 24 h after surgery.19 Nefopam 20 mg administered intravenously at 4 h intervals has been shown to be consistently superior to 2 g intravenous proparacetamol administered at the same intervals.8 In another study, postoperative morphine requirements were similar in patients receiving 20 mg nefopam or 10 mg ketamine following major surgery, indicating that both agents were comparable in enhancing postoperative analgesia.6

The high NRS scores seen at 1 h after surgery in the present study reflect the complexity of pain control in the immediate postoperative period. Patients are just recovering from drowsiness when they are transferred to the ward from PACU. Pain management may be insufficient but the use of opioids has to be weighed carefully against the risk of sedation. In addition, transferring from PACU to the ward and moving from bed to bed may cause additional stress for the patient. We conclude that more care should be given to improve the pain status during this transition period and that preoperative patient instructions on PCA use should be emphasised and perhaps a PCA bolus dose be given immediately before patients leave the PACU.

With the exception of dizziness and dry mouth, adding nefopam to the intravenous PCA did not appear to increase the incidence of opioid-related side effects such as nausea, vomiting, sedation, shivering, sweating and itching. Others have shown that AEs commonly associated with nefopam include tachycardia, sweating, nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, light headedness, asthenia, and pain at the injection site, but these are often transitory and moderate in severity.6,8,17,28 Nefopam does not suppress the central nervous system and has no respiratory depressive effect.29 Moreover, nefopam has a clear advantage over NSAIDs in that it does not cause gastric mucosal erosion or affect platelet aggregation.24 Although HR was significantly increased in the NF group compared with the SF group during the first 2 h and 24 h after surgery in the present study, there was no between-group difference in the incidence of tachycardia. The incidence of sweating, another commonly reported adverse event associated with nefopam, was not significantly different between groups, although two patients in NF group versus one in SF group experienced moderate-to-severe sweating. Tachycardia, sweating and, to a lesser extent, postoperative nausea and vomiting may be due to the antimuscarinic and sympathomimetic activity of nefopam,30 and related to its maximal concentration and rate of increase in plasma concentration.28 The dose of nefopam chosen for our study was relatively low (approximately 50 mg/day), and this may have influenced the occurrence of AEs reported here.

Although nefopam is considered well tolerated in therapeutic dose ranges, uncommon and sometimes fatal adverse events have been reported with this drug.31,32 For example, a case of postoperative permanent blindness31 and several cases of fatal intoxication.32 In addition, one study reported an unexpected increase in its plasma levels even though the doses were within the therapeutic range.33 Currently, there is no formal guidance for adjusting the dose of nefopam in cases of renal disease or in the elderly.28 However, decreased kidney function or end stage renal disease (ESRD) may result in abnormal accumulation of nefopam. The drug was found to exhibit a lower clearance and higher peak concentrations in patients with ESRD compared with healthy volunteers.34 The pharmacokinetics of nefopam may also be affected by age; one study estimated that for the same infusion duration of 20 mg of nefopam, three times lower total clearance and three times higher plasma concentrations of nefopam were observed in the elderly compared with younger subjects.28 Therefore, an infusion time of > 45 min for a single dose of nefopam and a 20 mg dose for the elderly are recommended to decrease the side-effects of nefopam.28 A limitation of the present study was the small sample size. Further, larger studies are therefore required to confirm these findings and provide more safety data.

In conclusion, intravenous PCA using nefopam + fentanyl following laparotomy has an opioid sparing effect and is associated with a low incidence of some of the typical opioid related AEs. The use of nefopam + fentanyl was associated with decreased intensity of pain, both at rest and on moving, and increased patient satisfaction at 24 h postsurgery, compared with fentanyl alone. Further studies with more patients are required to confirm these results and define the recommend dose and regimen of nefopam for intravenous PCA after laparotomy and other types of surgery.

Declaration of conflicting interests

YC Kim had support from Pharmbio Korea Co., Ltd., Korea for the submitted work.

Funding

This work was supported by the Pharmbio Korea Co., Ltd., Korea [grant number PBK1106ACU].

References

- 1.Tramoni G, Viale JP, Cazals C, et al. Morphine-sparing effect of nefopam by continuous intravenous injection after abdominal surgery by laparotomy. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2003; 20: 990–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lavand’homme P, De Kock M, Waterloos H. Intraoperative epidural analgesia combined with ketamine provides effective preventive analgesia in patients undergoing major digestive surgery. Anesthesiology 2005; 103: 813–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenach JC. Preventing chronic pain after surgery: who, how, and when? Reg Anesth Pain Med 2006; 31: 1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Subramaniam K, Subramaniam B, Steinbrook RA. Ketamine as adjuvant analgesic to opioids: a quantitative and qualitative systematic review. Anesth Analg 2004; 99: 482–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDaid C, Maund E, Rice S, et al. Paracetamol and selective and non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for the reduction of morphine-related side effects after major surgery: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess 2010; 14: 1–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kapfer B, Alfonsi P, Guignard B, et al. Nefopam and ketamine comparably enhance postoperative analgesia. Anesth Analg 2005; 100: 169–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carstensen M, Møller AM. Adding ketamine to morphine for intravenous patient-controlled analgesia for acute postoperative pain: a qualitative review of randomized trials. Br J Anaesth 2010; 104: 401–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mimoz O, Incagnoli P, Josse C, et al. Analgesic efficacy and safety of nefopam vs. propacetamol following hepatic resection. Anaesthesia 2001; 56: 520–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piercey MF, Schroeder LA. Spinal and supraspinal sites for morphine and nefopam analgesia in the mouse. Eur J Pharmacol 1981; 74: 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeong SH, Heo BH, Park SH, et al. Spinal noradrenergic modulation and the role of the alpha-2 receptor in the antinociceptive effect of intrathecal nefopam in the formalin test. Korean J Pain 2014; 27: 23–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verleye M, André N, Heulard I, et al. Nefopam blocks voltage-sensitive sodium channels and modulates glutamatergic transmission in rodents. Brain Res 2004; 1013: 249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klohs MW, Draper MD, Petracek FJ, et al. Benzoxacines: a new clinical class of centrally acting skeletal muscle relaxants. Arzneimittelforschung 1972; 22: 132–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richebé P, Picard W, Rivat C, et al. Effects of nefopam on early postoperative hyperalgesia after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2013; 27: 427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Girard P, Pansart Y, Coppe MC, et al. Nefopam reduces thermal hypersensitivity in acute and postoperative pain models in the rat. Pharmacol Res 2001; 44: 541–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tirault M, Derrode N, Clevenot D, et al. The effect of nefopam on morphine overconsumption induced by large-dose remifentanil during propofol anesthesia for major abdominal surgery. Anesth Analg 2006; 102: 110–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joo YC, Ko ES, Cho JG, et al. Intravenous nefopam reduces postherpetic neuralgia during the titration of oral medications. Korean J Pain 2014; 27: 54–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heel RC, Brogden RN, Pakes GE, et al. Nefopam: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs 1980; 19: 249–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tigerstedt I, Tammisto T, Leander P. Comparison of the analgesic dose-effect relationships of nefopam and oxycodone in postoperative pain. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1979; 23: 555–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans MS, Lysakowski C, Tramèr MR. Nefopam for the prevention of postoperative pain: quantitative systematic review. Br J Anaesth 2008; 101: 610–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim K, Kim WJ, Choi DK, et al. The analgesic efficacy and safety of nefopam in patient-controlled analgesia after cardiac surgery: a randomized, double-blind, prospective study. J Int Med Res 2014; 42: 684–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oh CS, Jung E, Lee SJ, et al. Effect of nefopam- versus fentanyl-based patient controlled analgesia on postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing gynecological laparoscopic surgery: a prospective double-blind randomized controlled trial. Curr Med Res Opin 2015; 31: 1599–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hwang BY, Kwon JY, Lee DW, et al. A randomized clinical trial of Nefopam versus Ketorolac combined with oxycodone in patient-controlled analgesia after gynecologic surgery. Int J Med Sci 2015; 12: 644–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du Manoir B, Aubrun F, Langlois M, et al. Randomized prospective study of the analgesic effect of nefopam after orthopaedic surgery. Br J Anaesth 2003; 91: 836–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dordoni PL, Della Ventura M, Stefanelli A, et al. Effect of ketorolac, ketoprofen and nefopam on platelet function. Anaesthesia 1994; 49: 1046–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morgan & Mikhail’s Clinical Anesthesiology, 5th edition, John f. Butterworth, David C. Mackey, John D. Wasnick. Ch.18, P297.

- 26.Breivik H, Borchgrevink PC, Allen SM, et al. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth 2008; 101: 17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chernik DA, Gillings D, Laine H, et al. Validity and reliability of the Observer’s Assessment of Alertness/ Sedation Scale: study with intravenous midazolam. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1990; 10: 244–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Djerada Z, Fournet-Fayard A, Gozalo C, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of nefopam in elderly, with or without renal impairment, and its link to treatment response. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014; 77: 1027–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhatt AM, Pleuvry BJ, Maddison SE. Respiratory and metabolic effects of oral nefopam in human volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1981; 11: 209–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sweetman SC. Martindale. The complete drug reference, 36th ed. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2009, p.94.

- 31.Corbonnois G, Iohom G, Lazarescu C, et al. Unilateral permanent loss of vision after nefopam administration. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2013; 32: e113–e115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Durrieu G, Olivier P, Bagheri H, et al. Overview of adverse reactions to nefopam: an analysis of the French Pharmacovigilance database. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2007; 21: 555–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ould-Ahmed M, Drouillard I, El-Kartouti A, et al. Nefopam by continuous intravenous injection and adverse drug reactions: which causality assessment? Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2007; 26: 74–76. [in French, English Abstract]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mimoz O, Chauvet S, Grégoire N, et al. Nefopam pharmacokinetics in patients with end-stage renal disease. Anesth Analg 2010; 111: 1146–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]