Abstract

Objective

This study assessed the mode of application (oral, intravenous or subcutaneous (SC)) currently employed in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in patients from Qatar in comparison with patients’ individual preferences for the mode of application of their treatment.

Methods

This study included 294 RA patients visiting three clinics at the main referral hospital in Qatar who were interviewed using a standard questionnaire to determine their preference of mode of application for their disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) treatment in relation to their currently employed mode of application.

Results

The majority of patients were female (76%), and 93% of male patients and 61% of female patients in the study clinics were of a nationality other than Qatari. The highest patient preference recorded was for an oral therapy (69%), compared with injection (23%) and intravenous (8%) therapy. In total, 85% of patients expressed a preference to remain on oral therapy compared with 63% and 58% of intravenous and SC injection patients indicating a preference to remain on their current method of administration.

Conclusions

This high preference for oral therapies highlights the considerable need for incorporation of new oral targeted synthetic DMARD therapies into clinical practice within the region.

Keywords: Rheumatoid arthritis, patient preference, temperature, fasting, route of administration, novel oral therapies, patient profile, Middle East, Qatar, Arabian Gulf

Introduction

Despite the introduction of biologic therapies for the treatment of inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in the 1990s, there remain many unmet needs in the modern management of rheumatology at a global level. However, this global perspective cannot reflect the individual situations of patients in different countries and regions. Consequently, specific regional unmet needs are deserving of special examination, and here we will focus on RA patients in Qatar. The hot, humid climate, healthcare system and population demographics in this area of the world attribute unique considerations for practising rheumatologists in this region that may differ to those of specialists treating RA in the rest of the world. New therapies are currently being developed that aim to address some of these unmet needs, including novel oral therapies such as targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (tsDMARDs).1 It is widely expected that patients will prefer to receive an oral therapy over a subcutaneous (SC) or intravenous (IV) one,2,3 but this may not be the case for all groups. Additionally, there are concerns about compliance and wasted drug with oral medication. To give regional guidance on the use of newly available therapies, we have conducted a patient preference and profile survey, the results of which are presented here alongside a review of the situation in Qatar and the wider Arabian Gulf region.

RA management in the Arabian Gulf

RA is a chronic inflammatory disease with an estimated prevalence of 0.5–1% in Northern Europe and North America.4 However, there are few large epidemiological studies or good-quality registry data to suggest the disease’s overall prevalence in the region of the Arabian Gulf.5–7 Small population and hospital-based studies give wide variation, from 0.19% in rural Iran to 1.0% of the adult population in Lebanon and Iraq.8–12 In Oman, the prevalence of RA in the population has been calculated at 8.4 cases per 1,000 adults (0.84%).13

Disease severity also varies geographically, and it has traditionally been believed that most Arab patients with RA have a non-aggressive form of the disease.5,14 These beliefs may lead to significant delays in diagnosis and treatment.15 However, the disease severity is, in fact, comparable to that seen in other parts of the world,15–17 with physicians reporting only 12% of patients in clinical practice having low disease activity in this region (LDA; defined as disease activity score (DAS) 28 < 3.2).16

It has long been accepted that there are cultural differences in how RA is managed in the Middle East.18 Management practices vary widely – often depending on the socioeconomic status of individual patients and complicated by local infrastructure or lack of it – but there are signs that disease management strategy is evolving in the Middle East – and the Gulf states in particular – and many clinicians are now implementing up-to-date treatment guidelines and recommendations from international societies.5,15 In Qatar, the majority of patients receive conventional synthetic (cs) DMARDs, and 64% of patients seen in the clinic achieve LDA or remission.19 Yet despite this move towards modern practice, RA patients often experience a delay in diagnosis: a recent study in Dubai found erosions in 55% of patients, suggesting a delay in diagnosis and management.16 A review examining the use of the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations in this region found that there were barriers to implementation, mainly for those individual recommendations that advocated aggressive management, early use of intensive therapy and frequent monitoring.15 There still exists a significant regional unmet need in the management of RA.

Regional environmental considerations in the management of RA

There are certain regional environmental considerations that impact the management of RA patients. The first of these relates to the climate, as summer temperatures in Qatar can surpass 49℃.20 To prevent disruption of the “cold chain,” biologic drugs are dispensed in a chilled bag from the pharmacy. Although air conditioning is common in cars and homes, it is not entirely ubiquitous for the poorest in society and there is a risk that medication may be spoiled.

Ramadan fasting – a fundamental pillar of Islam – may have an effect on patient compliance and disease activity.21,22 Whilst patients with chronic diseases may not be required to fast during Ramadan, many still do, and this has an impact on adherence and disease activity.22 Many patients prefer not to take oral or intravenous medications during fasting hours,21 and as such, patients might only take their therapies after sunset and before sunrise.23–25 This alteration in dosing schedule has a clear impact on compliance.21 Some patients may not agree to medical procedures such as blood tests during Ramadan, which may have an impact on routine monitoring.21 Anecdotally, RA patients often do better during Ramadan and feel well because they are fasting, but then flare afterwards.26,27 There is some speculation that this may be because the foods traditionally eaten during the Ramadan month are better for RA patients than those consumed during the rest of the year, including an increase in protein consumption and a reduction in carbohydrate intake, and that fasting has a direct effect on laboratory parameters.26–28 An important take-home point from the studies discussed here is that most patients did not receive any particular information about changing their treatment during Ramadan. More research is required in this area to further understand the effects of Ramadan on adherence and disease activity.

Given the unmet needs in this region, this study aimed to investigate the level of disease activity in the region and patients’ preferences regarding the route of administration for their therapy.

Methods

The authors met at a face-to-face meeting in September 2014. On the basis of discussions, a cross-sectional patient survey was designed to collect data on the typical RA patient profile in the region (Box 1). The survey was conducted among 294 consecutive patients across three clinics in Qatar. Ethics committee approval was waivered for this study as all RA patients at the three participating clinics within Qatar are registered in the regional RA registry, for which they provide signed consent for their data to be used for publication purposes. The predefined primary clinical end point was the preferred mode of application (oral, IV, SC) in comparison with the patient’s currently employed mode of application for treatment and in relation to their disease activity. Summary statistics are reported as either a mean with the minimum and maximum range for continuous data (such as the age of the patient) or as a total for count data (such as the number of patients on each mode of application).

Box 1.

Survey questions.

| • Demographics: patient age, gender and nationality |

| • Disease activity score (DAS) |

| • Clinical disease activity score (CDAI) |

| • Current route of administration |

| ^ Oral alone |

| ^ Injection ± oral |

| ^ Intravenous ± oral |

| • Preferred route of administration |

| • Co-morbidities |

Table 1.

Demographics in 294 consecutive patients at three clinics in Qatar.

| Male (n = 71) |

Female (n = 223) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qatari national | Other | Qatari national | Other | |

| Number, n (%) | 5 (7) | 66 (93) | 87 (39) | 136 (61) |

| Age, mean years (range) | 51.2 (31–64) | 51.1 (24–75) | 50.8 (20–84) | 46.9 (16–73) |

Descriptive statistics were employed for the analysis of baseline demographics. Among the population analysed, the patients´ nationality was dichotomized into Qatari and non-Qatari patients.

The mode of application employed and preferred was analysed separately for IV, SC and oral administration. Whether patients treated with a certain mode of application were pre-treated with another mode of application was not analysed in this survey. For the analysis of co-morbid diseases the results focussed on cardiovascular conditions (including diabetes, hypertension, hyper/dyslipoproteinemia or other), none and not reported.

Results

In our patient survey, 76% of patients in the study clinics were female. The mean age for women was 48 years (range 16–84), and 51 years for men (range 24–75). Our patient survey also captured the split between Qatari nationals and non-Qatari nationals, with 93% of male patients and 61% of female patients in the study clinics being of a nationality other than Qatari (Table 1).

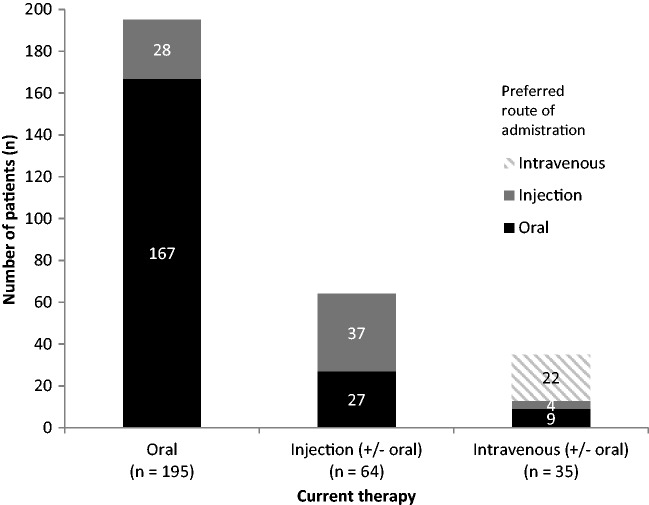

Of the 294 patients in our survey across three clinics in Qatar, 69% expressed a preference for oral therapy, 23% for SC injection and 8% for intravenous administration (Table 2). Highest patient preference was for oral therapy, with 85% of patients who received it expressing a preference to stay on oral therapy. In contrast, only 63% and 58% of intravenous and SC injection patients, respectively, indicated a preference to remain on their current method of administration (Figure 1). The mean age of patients with recorded co-morbidities was 55 years (range 17–74), with 88 patients (30%) diagnosed with one or more cardiovascular diseases (Table 3).

Table 2.

Survey results: Route of administration and patient preference in 294 consecutive patients seen at three clinics in Qatar.

| Male (n = 71) |

Female (n = 223) |

Total (N = 294) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qatari national (n = 5) | Other (n = 66) | Qatari national (n = 87) | Other (n = 136) | ||

| Current therapy | |||||

| Oral alone, n (%) | 3 (60.0) | 51 (77.0) | 44 (51.0) | 97 (71.0) | 195 (66.0) |

| Subcutaneous injection ± oral, n (%) | 1 (20.0) | 5 (8.0) | 28 (32.0) | 30 (22.0) | 64 (22.0) |

| Intravenous ± oral, n (%) | 1 (20.0) | 10 (15.0) | 15 (17.0) | 9 (7.0) | 35 (12.0) |

| Preferred route of administration | |||||

| Oral alone, n (%) | 3 (60.0) | 49 (74.0) | 53 (61.0) | 99 (73.0) | 203 (69.0) |

| Subcutaneous injection ± oral, n (%) | 1 (20.0) | 12 (18.0) | 23 (26.0) | 32 (24.0) | 69 (23.0) |

| Intravenous ± oral, n (%) | 1 (20.0) | 5 (8.0) | 11 (13.0) | 5 (3.0) | 22 (8.0) |

Figure 1.

Patient-preferred route of administration in comparison with current therapeutic route of administration – current versus desired in 294 consecutive patients seen at three clinics in Qatar.

Table 3.

Survey results: Cardiovascular co-morbidities among patients at three clinics in Qatar*.

| Male (n = 71) |

Female (n = 223) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qatari national (n = 5) | Other (n = 66) | Qatari national (n = 87) | Other (n = 136) | |

| One or more cardiovascular co-morbidity, n (%) | 1 (50.0) | 16 (23.2) | 17 (19.6) | 44 (35.4) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 0 (0) | 6 (8.7) | 7 (8.0) | 18 (13.2) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 1 (50.0) | 10 (14.5) | 8 (9.2) | 27 (19.9) |

| Hyperlipidemia, dyslipidaemia or hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 0 (50.0) | 4 (5.8) | 8 (9.2) | 8 (5.9) |

| Other, n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.9) | 10 (11.5) | 8 (5.9) |

| None, n (%) | 0 (0) | 17 (24.6) | 38 (43.7) | 31 (22.8) |

| Not reported, n (%) | 1 (50.0) | 36 (52.2) | 32 (36.8) | 61 (44.9) |

Data received from 56% of patients surveyed.

The level of disease activity in RA patients is most commonly measured via DAS and/or clinical disease activity index (CDAI). The level of disease activity can be interpreted as low (2.6 < DAS28 ≤ 3.2) (2.8 < CDAI ≤ 10), moderate (3.2 < DAS ≤ 5.1) (10 < CDAI ≤ 22), or high (DAS > 5.1) (CDAI > 22) with a DAS ≤ 2.6 or CDAI ≤ 2.8 corresponding to remission.29 In our survey, whilst DAS was recorded in only 256 patients, CDAI was recorded in all 294 (mean overall score 9.07; range 0–55). There was agreement between DAS and CDAI in 79% of the cases. In the remaining patients, two-thirds showed a DAS higher than the CDAI and one-third had a CDAI higher than DAS (Table 4). Our results show that, among the patients in our survey, over half had not yet achieved a CDAI LDA score (2.8 CDAI ≤ 10) with their current treatment (Table 4).

Table 4.

Disease activity in 294 consecutive patients at three clinics in Qatar*.

| Male (n = 71) |

Female (n = 223) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qatari national (n = 5) | Other (n = 66) | Qatari national (n = 87) | Other (n = 136) | Total (N = 294) | |

| CDAI, mean (range) | 1.90 (0–5) | 9.34 (0–55) | 9.35 (0–52) | 9.03 (0–43.9) | 9.07 (0–55) |

| CDAI LDA, n (%) | 1 (0.3) | 27 (9.2) | 36 (12.2) | 67 (22.8) | 131 (44.5) |

| CDAI remission, n (%) | 4 (1.4) | 18 (6.1) | 21 (7.1) | 26 (8.8) | 69 (23.4) |

| DAS*, mean (range) | 2.07 (1.3–3.1) | 3.28 (0.63–6.92) | 3.52 (1.25–7.21) | 3.57 (0.56–6.84) | 3.47 (0.56–7.21) |

| DAS LDA, n† | 1 | 9 | 12 | 17 | 39 |

| DAS remission, n† | 4 | 19 | 22 | 32 | 77 |

CDAI: clinical disease activity index; DAS: disease activity score; LDA: low disease activity.

DAS was calculated on only those patients with relevant data available (n = 256).

†The percentage of patients with an LDA or remission DAS score was not calculated as DAS scores were not collected for all patients.

Among patients surveyed for whom the level of disease activity was recorded, the majority (70%) with a recorded DAS of LDA or remission preferred the option of an oral therapy. The majority of patients with a recorded DAS of high disease activity also preferred the option of an oral therapy (77%). These high percentages for a preferred oral therapy were also reflected across the CDAI scores collected in our survey. Of those patients with a CDAI score of LDA or remission, 53% preferred the option of an oral therapy, and of those with a CDAI score of high disease activity, 74% preferred the option of an oral therapy.

Discussion

Social and access considerations

Several key social considerations have a bearing on access to therapy for RA patients in the Arabian Gulf. A patient’s preferred route of administration for their therapy is often cited as a barrier to receiving therapy. It is assumed that patients prefer oral therapy, and several studies across a variety of chronic diseases have indeed found this pattern.30–34 Research suggests that 44% of RA patients are not confident in administering their own injections.2 Patients in these countries are also often undertreated5,16 and there is wide variation in treatment, with 5% of patients in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and 29% in Qatar receiving a biologic, compared with over 40% of eligible patients in the USA.19 In part, this can be attributed to the high socioeconomic burden of other more prevalent diseases in the Middle East and Arabian Gulf countries, such as diabetes.15 Public awareness regarding RA is also generally low in the region, but data from the UAE show that the introduction of patient support groups and disease awareness campaigns are beginning to show an effect.35

Of particular note are the population dynamics, which are unique in the region and have a direct impact on healthcare provision and health economics. In particular, Qatar has an unusually high rate of temporary expatriates: Qatari nationals make up only about 6% of the overall adult population, with the majority of the country’s residents being migrant workers from Asia, Africa and Europe.36 In a recent cross-sectional study of 100 consecutive rheumatology patients at Hamad General Hospital in Doha, less than a quarter of patients were Qatari nationals; the majority (59%) were immigrant workers from Asia. Most of the Qatari patients were female (91%) compared with only 53% of the Asian patients, which reflects the high proportion of male immigrant workers.19 In our survey, we found that less than a third of patients from the three clinics were Qatari nationals and that these were almost exclusively women (95%), compared with only 67% of non-national female patients.

This population skew has a direct bearing on clinical practice, since Qatari nationals receive free healthcare but non-Qatari immigrants do not – although those with a residency visa have free access to primary and emergency healthcare services and pay only 20% of the costs of speciality healthcare services and drugs.19 The Doha study found that 65% of Qatari national patients received biologic therapies, compared with 15% of eligible Asian immigrants.19 Whilst some workers have medical insurance, the majority of immigrant labourers do not, and they cannot always pay for treatment. It is quite typical for these patients to visit their rheumatologist only when they can afford it, and this means that they are often untreated and flaring. Additionally, workers may return to their home country for extended periods between contracts and, as such, they are lost to follow-up in the clinic. This high proportion of expatriates and lack of appropriate medical insurance were cited as key reasons why physicians in countries in the region have been unable to implement the EULAR recommendations in clinical practice.15 The results of our survey align with the region, representing varying and heterogeneous patient populations and the challenge this presents for clinicians looking to adopt guidelines or recommendations.5 By the end of 2015, under new compulsory health insurance legislation in Qatar, it will be a requirement for companies to insure all non-Qatari workers,37 although the policies may not cover modern biologic therapies. For these workers, in particular, affordable oral therapies that can easily be transported and self-administered may prevent patients from taking breaks from therapy that may cause serious long-term damage to their joints.

The literature reports typical patient profiles in the Arab region as being predominantly female, with a mean age of around 40 years at assessment.12,19,35,38–40 Patient age is an important factor that may also impact treatment decisions41 – not least because older patients tend to have more co-morbidities, such as diabetes and heart failure. In our survey, the mean age of patients with recorded co-morbidities was 55 years (range 17–74), with 88 patients (30%) diagnosed with cardiovascular diseases (Table 3). These numbers are of particular importance – in 2012, four Gulf Cooperation Council countries (Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar and Bahrain) were among the top ten countries for highest diabetes prevalence rates in the world, with 20.52%, 17.87%, 16.28% and 17.53% of patients affected, respectively.42

There are several limitations to this study. First, only the mode of application of treatment was assessed through the survey; therapy type was not specified, with no direct comparisons between different therapies being drawn. Second, further clinical subgroups, including length of time on treatment, socioeconomic status and patient-reported outcomes, were not defined. Future research into these areas could further build upon the current landscape and patient profiles within the region.

The future of RA therapy

Whilst there are clear unmet needs remaining for RA patients in the Arabian Gulf region, there are new oral tsDMARD therapies both available and in development that may offer some benefit. As well as the obvious benefits for needle-phobic patients or those who are unwilling or unable to inject themselves, these therapies are expected to be cheaper than biologics and will not be subject to the same requirements for cold storage, which may make them more suitable for populations exposed to hot summers and periods of travel. Additionally, new oral tsDMARD therapies can be taken with or without food,43 and are therefore not expected to have any food interactions that would complicate the dosing schedule during Ramadan. However, these new therapies will require a shift in clinical practice to be accommodated.

Our group’s clinical advice for rheumatologists considering using new oral tsDMARD therapies in their patients is based on the European and US experience to date.44–46 Patients with autoimmune diseases, such as RA, are at increased risk for infections,45 but biologic and new oral tsDMARD therapies may make patients more susceptible to opportunistic infections.47 At the forefront are recommendations for vaccination against herpes zoster (HZ), as high numbers of cases of HZ were observed in clinical trials of some new therapies.48 The routine measurement of varicella titres in patients is recommended: patients found to have a protective range can safely start therapy, but those with low titres should receive varicella or zostervax vaccine 2–3 weeks before starting therapy. Individual vaccination status should always be checked by the rheumatologist and updated prior to the initiation of any immunomodulatory therapy.44,46 Tuberculosis (TB) has a prevalence of 3–43/100,000 persons in the region.49 The advice and recommendations for the prevention and management of TB in patients receiving new oral tsDMARD therapies are the same as those for biologics, with new patients receiving a skin test prior to initiation of therapy and every year thereafter.

It is this group’s recommendation that all physicians should endeavour to record the CDAI for every patient to gain a full picture of the disease burden and pattern. In order for disease remission to be an implementable target, both in clinical studies and in practice, it needs to be easy to calculate at the bedside. Aletaha et al.50 demonstrated that simpler composite indices using an arithmetic sum of the same components (SDAI and CDAI) correlate well with DAS. Recently, in Qatar, there has been a change in clinical practice in the use of disease measurements. It is becoming increasingly common to record the CDAI at every patient visit, although DAS is still used for registry data collection.

Despite advances in treatment and management strategies, discord and misconception around the prevalence, severity and burden of RA persist in the Arabian Gulf region and represent a key barrier to early and appropriate treatment.15 Overall, a preference for oral therapies over injection or infusion was observed in this study, and the greatest patient preference was for oral therapies. Whilst this survey did not capture the reasons for the patients’ preferred route of administration, it is suspected that oral therapy is considered more convenient in this highly mobile, working population. On this basis, we recommend that the incorporation of new oral tsDMARD therapies into clinical practice will help to fulfil the current unmet treatment needs and alleviate the burden on patients and healthcare resources.

Compliance with ethical standards

Declaration of conflicting interest

Samar Al-Emadi is a consultant for Pfizer.

Mohammed Hammoudeh received research grants from Pfizer, Roche and Schering-Plough and consultation honorarium from Pfizer, Roche and Abbott.

Mohamed Mounir is an employee of Pfizer.

Ruediger B. Mueller is a consultant for Pfizer.

Alvin F. Wells is a consultant for Pfizer.

Housam Aldeen Sarakbi has received financial support from Wyeth, Roche, Pfizer, Jansen, Schering-Plough, Abbott and New Bridge.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were deemed as low risk and therefore in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Funding

The development of this manuscript was funded by Pfizer. Editorial support and assistance were provided by Synergy Medical.

References

- 1.Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73: 492–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chilton F, Collett RA. Treatment choices, preferences and decision-making by patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Musculoskelet Care 2008; 6: 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krüger K, Alten R, Schiffner-Rohe J, et al. Patient preferences in the choice of disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs. Presented at EULAR 2015, Rome, Italy. Poster THU0350, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Alamanos Y, Drosos AA. Epidemiology of adult rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun Rev 2005; 4: 130–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halabi H, Alarfaj A, Alawneh K, et al. Challenges and opportunities in the early diagnosis and optimal management of rheumatoid arthritis in Africa and the Middle East. Int J Rheum Dis 2015; 18: 268–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hajjaj-Hassouni N, Al-Badi M, Al-Heresh A, et al. The practical value of biologics registries in Africa and Middle East: challenges and opportunities. Clin Rheumatol 2012; 31: 407–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Symmons D, Mathers C and Pfleger B. The global burden of rheumatoid arthritis in the year 2000. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/bod_rheumatoidarthritis.pdf. Accessed 27/01/2015.

- 8.Chaaya M, Slim ZN, Habib RR, et al. High burden of rheumatic diseases in Lebanon: a COPCORD study. J Rheum Dis 2012; 15: 135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davatchi F, Jamshidi AR, Banihashemi AT, et al. WHO-ILAR COPCORD study (stage 1, urban study) in Iran. J Rheumatol 2008; 35: 1384–1384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moghimi N, Davatchi F, Rahimi E, et al. WHO-ILAR COPCORD study (stage 1, urban study) in Sanandaj, Iran. Clin Rheumatol 2015; 34: 535–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandoughi M, Zakeri Z, Tehrani Banihashemi A, et al. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in southeastern Iran: a WHO-ILAR COPCORD study (stage 1, urban study). Int J Rheum Dis 2013; 16: 509–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Rawi ZS, Alazzawi AJ, Alajili FM, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis in population samples in Iraq. Ann Rheum Dis 1978; 37: 73–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pountain G. The prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in the Sultanate of Oman. Br J Rheumatol 1991; 30: 24–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.al Attia HM, Gatee OB, George S, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis in a population sample in the Gulf: clinical observations. Clin Rheumatol 1993; 12: 506–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El Zorkany B, Alwahshi HA, Hammoudeh M, et al. Suboptimal management of rheumatoid arthritis in the Middle East and Africa: could the EULAR recommendations be the start of a solution? Clin Rheumatol 2013; 32: 151–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Badsha H, Kong KO, Tak PP. Rheumatoid arthritis in the United Arab Emirates. Clin Rheumatol 2008; 27: 739–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alawneh KM, Khassawneh BY, Ayesh MH, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis in Jordan: a cross sectional study of disease severity and associated comorbidities. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2014; 10: 363–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El Meidany YM, El Gaafary MM, Ahmed I. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of an Arabic health assessment questionnaire for use in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Joint Bone Spine 2003; 70: 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luft A, Poil A, Hammoudeh M. Characteristics of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Qatar: a cross-sectional study. Int J Rheum Dis 2014; 17: 63–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdul-Wahhab SA, Al-Saifi SY, Alrumhi BA, et al. Determination of the features of the low-level temperature inversions above a suburban site in Oman using radiosonde temperature measurements: Long-term analysis. J Geophys Res 2014; 109: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ali R, Siddiqui H, Anjum Q, et al. Knowledge and perception of patients regarding medicine intake during Ramadan. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2007; 17: 112–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aadil N, Houti IE, Moussamih S. Drug intake during Ramadan. BMJ 2004; 329: 778–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aslam M, Assad A. Drug regimens and fasting during Ramadan: a survey in Kuwait. Public Health 1886; 100: 49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aslam M, Healy MA. Compliance and drug therapy in fasting Moslem patients. J Clin Hosp Pharm 1986; 11: 321–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aslam M, Wilson JV. Medicines, health and the fast of Ramadan. J R Soc Health 1992; 112: 135–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Said MSM, Vin SX, Azhar NA, et al. The effects of the ramadan month of fasting on disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Turk J Rheumatol 2013; 28: 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Dubeikil KY, Abdul-Lateef WK. Ramadan fasting and rheumatoid arthritis. Bahrain Medical Bulletin 2003; 25: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gharbi M, Akrout M, Zouari B. Food intake during and outside Ramadan. East Mediterr Health J 2003; 9: 131–140. [in French, English Abstract]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson JK, Zimmerman L, Caplan L, et al. Measures of rheumatoid arthritis disease activity. Arthritis Care & Research 2011; 63: S14–S36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fallowfield L, Atkins L, Catt S, et al. Patients’ preference for administration of endocrine treatments by injection or tablets: results from a study of women with breast cancer. Ann Oncol 2006; 17: 205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohr DC, Boudewyn AC, Likosky W, et al. Injectable medication for the treatment of multiple sclerosis: the influence of self-efficacy expectations and injection anxiety on adherence and ability to self-inject. Ann Behav Med 2001; 23: 125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kendler DL, Bessette L, Hill CD, et al. Preference and satisfaction with a 6-month subcutaneous injection versus a weekly tablet for treatment of low bone mass. Osteoporos Int 2010; 21: 837–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karter AJ, Subramanian U, Saha C, et al. Barriers to insulin initiation: the translating research into action for diabetes insulin starts project. Diabetes Care 2010; 33: 733–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerber RA, Cappelleri JC, Kourides IA, et al. Treatment Satisfaction with inhaled insulin in patients with type 1 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2001; 24: 1556–1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zafar S, Badsha H, Mofti A, et al. Efforts to increase public awareness may result in more timely diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol 2012; 18: 279–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qatar Information Exchange. http:qix.gov.qa/discoverer. Accessed 02/02/2015.

- 37.Mercer Insights. Qatar Compulsory Health Insurance – Are You Ready? http://www.me.mercer.com/content/mercer/middle-east-and-africa/me/en/insights/point/2014/qatar-compulsory-health-insurance-are-you-ready.html Accessed 03/02/2015.

- 38.Alballa SR. The expression of rheumatoid arthritis in Saudi Arabia. Clin Rheumatol 1995; 14: 641–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalouche Khalil L, Baddoura R, Okais J, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis in Lebanese patients: characteristics in a tertiary referral centre in Beirut city. Ann Rheum Dis 2006; 65: 684–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al-Temimi F. The spectrum of rheumatoid arthritis in patients attending rheumatology clinic in Nizwa hospital Oman. Oman Med J 2010; 25: 184–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mueller RB, Kaegi T, Finckh A, et al. Is radiographic progression of late-onset rheumatoid arthritis different from young-onset rheumatoid arthritis? Results from the Swiss prospective observational cohort. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014; 53: 671–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.IDF Diabetes Atlas 6th Edition. 2014 update. https://www.idf.org/sites/default/files/Atlas-poster-2014_EN.pdf. Accessed 26 January 2016.

- 43.Cada DJ, Demaris K, Levien TL, et al. Tofacitinib. Hosp Pharm 2013; 48: 413–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rahier JF, Moutschen M, Van Gompel A, et al. Vaccinations in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010; 49: 1815–1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Müller-Ladner C, Müller-Ladner U. Vaccination and inflammatory arthritis: overview of current vaccines and recommended uses in rheumatology. Clin Rheumatol Rep 2013; 15: 330–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Assen S, Agmon-Levin N, Elkayam O, et al. EULAR recommendations for vaccination in adult patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 2011; 70: 414–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramiro S, Gaujoux-Viala C, Nam JL, et al. Safety of synthetic and biological DMARDs: a systematic literature review informing the 2013 update of the EULAR recommendations for management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73: 529–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Winthrop KL, Yamanaka H, Valdez H, et al. Herpes zoster and tofacitinib therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014; 66: 2675–2684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hammoudeh M, Alarfaj A, Chen DY, et al. Safety of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors use for rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia: focus on severe infections and tuberculosis. Clin Rheumatol 2013; 32: 293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aletaha D, Ward MM, Machold KP, et al. Remission and active disease in rheumatoid arthritis: defining criteria for disease activity states. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52: 2625–236–2625–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]