Abstract

Objective

To quantify T helper (Th)17 cells and determine interleukin (IL)-17A levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) culture and vitreous fluid from patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) with diabetic retinopathy (DR).

Methods

Th17 cell frequency and IL-17A concentrations in PBMCs from 60 patients with T2DM with DR, 30 without DR and 30 sex- and age-matched healthy individuals were measured by flow cytometry and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), respectively. IL-17A levels in vitreous fluid from 31 eyes with proliferative DR and diabetic macular oedema (DR group) and 32 eyes with an epiretinal membrane and macular hole (control group) that underwent vitrectomy were also examined by ELISA.

Results

Compared with the control group, the proportion of Th17 cells and IL-17A concentrations in PBMCs were significantly increased in patients without DR but decreased in those with DR. IL-17A concentrations and Th17 cell frequency in PBMCs tended to decrease with DR severity and were negatively correlated with body mass index, T2DM duration and glycated haemoglobin. Additionally, vitreous fluid IL-17A levels were significantly elevated in patients with DR compared with those of the control group.

Conclusions

We conclude that disturbances in Th17 cells and IL-17A levels are possibly associated with DR.

Keywords: Diabetic retinopathy, interleukin-17A, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, T helper 17 cells, type 2 diabetes mellitus

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a latent disorder that is increasing globally and expected to affect 300 million people by 2025.1 Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is the most prevalent type of diabetes.2 Recently, the involvement of inflammation and immune mechanisms has been studied extensively in T2DM.3–7

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a common complication of diabetes and is the primary cause of postnatal blindness.8 There is increasing evidence that the inflammatory process may play an important role in DR pathogenesis and progression. Elevated inflammatory cytokine, chemokine and growth factor levels can be detected in vitreous fluids and the aqueous humour of patients with DR.9–15 However, the pathogenesis underlying DR remains to be defined. Recent studies have indicated that an autoimmune mechanism is involved in the proliferative stage of DR. Yet, little information is available regarding immune disturbances in patients with T2DM with DR, particularly the role of T helper (Th) cells and their immune function.16–18 Our previous study demonstrated that PBMC interleukin (IL)-22 levels were significantly elevated in patients with proliferative DR, indicating a possible role for Th22 cells.19 Moreover, another subset of effector CD4+Th cells, Th17 cells, have been implicated in T2DM pathogenesis. Th17 cells are a new T-cell lineage characterized by the production of IL-17A. A recent study revealed that Th17 cells and IL-17A levels were elevated in patients with T2DM, which likely promoted chronic inflammation.20 Whether similar immune mechanisms are also involved in DR is presently unknown. Therefore, it is important to determine Th17 cell behaviour, particularly in mononuclear cells, associated with DR to identify underlying mechanisms in patients with T2DM.

In the present study, we compared IL-17A production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from patients with T2DM with or without DR and healthy volunteers. We investigated the Th17 cell frequency among PBMCs. IL-17A concentrations in the vitreous fluid of eyes from patients with DR and control eyes with an epiretinal membrane and macular hole were also analysed. Finally, we established whether IL-17A concentrations and Th17 cell frequency were related to DR severity.

Methods

Subjects and sample preparation

We selected 60 patients with T2DM with DR and 30 without DR from the Outpatient Clinics at the Zhongshan Ophthalmic Centre, China, and 30 healthy, non-smoking volunteers (Table 1). T2DM diagnosis was confirmed using the American Diabetes Association, 2002 standards.21 We excluded patients with infectious diseases or other diabetic complications, such as nephropathy, and those using immunosuppressive drugs. DR was assessed by fluorescein fundus angiography (FF450 fundus camera; Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Jena, Germany). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2). DR was classified according to the new international classification standard.22 Patients with DR were divided into two groups: nonproliferative DR (NPDR; n = 30; 16 male and 14 female) and proliferative DR (PDR; n = 30; 15 male and 15 female) (Table 2). The project followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and all experimental protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee at our institution. Patients gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Table 1.

Clinical and biochemical characteristics of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus without retinopathy (NDR) and with retinopathy (DR) and non-diabetic control subjects.

| Control subjects (N = 30) | NDR (N = 30) | DR (N = 60) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (m/f) | 17/13 | 12/18 | 31/29 | 0.407 |

| Age (years) | 62.67 ± 9.09 | 59.43 ± 7.73 | 61.30 ± 6.44 | 0.248 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.63 ± 1.89 | 21.76 ± 1.72 | 23.46 ± 2.97 | <0.001* |

| Diabetes duration (years) | − | 7.90 ± 3.16 | 14.38 ± 3.71 | <0.001* |

| FPG (mg/dl) | 81.07 ± 5.69 | 152.36 ± 12.13 | 176.15 ± 11.66 | <0.001* |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.25 ± 0.58 | 7.89 ± 1.36 | 8.45 ± 1.37 | <0.001* |

NDR, type 2 diabetes mellitus without diabetic retinopathy; DR, diabetic retinopathy; BMI, body mass index; f, female; FPG: fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; m, male.

Data are expressed as mean ± SD.

Table 2.

Clinical and biochemical characteristics of patients with nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) and proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR).

| NPDR (N = 30) | PDR (N = 30) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (m/f) | 16/14 | 15/15 | 0.796 |

| Age (years) | 62.27 ± 6.52 | 60.33 ± 6.33 | 0.249 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.03 ± 2.93 | 23.89 ± 3.00 | 0.265 |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 13.23 ± 4.00 | 15.53 ± 3.04 | 0.015* |

| FPG (mg/dl) | 169.33 ± 10.54 | 182.97. ± 8.33 | <0.001* |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.93 ± 0.89 | 8.97 ± 1.57 | 0.003* |

NPDR, non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy; PDR, proliferative retinopathy; BMI, body mass index; f, female; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; m, male.

Data are expressed as mean ± SD.

A whole blood sample (12 ml) was obtained from each study participant and placed in a sterile tube containing lithium heparin as an anticoagulant (Vacutainer; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) for the cell proliferation test and cytokine quantification. Additional blood samples were obtained for the measurement of fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels.

An initial pars plana vitrectomy was performed [n = 63 total; n = 31 with proliferative DR and/or diabetic macular edema (DR group) and n = 32 with an epiretinal membrane and macular hole (control group)] followed by a vitreous fluid assay. Patient backgrounds are summarized in Table 3. Approximately 0.3 ml of undiluted vitreous fluid was collected from each eye with a plastic syringe using a vitreous cutter, and vacuum pressure was manually applied before perfusion initiation during the initial vitrectomy procedure.

Table 3.

Clinical and biochemical characteristics of patients with diabetic retinopathy (DR) and healthy controls that underwent vitrectomy.

| Control (N = 32) | DR (N = 31) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (m/f) | 18/14 | 16/15 | 0.802 |

| Age (years) | 60.75 ± 6.46 | 60.74 ± 5.85 | 0.996 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.62 ± 1.90 | 23.85 ± 2.94 | <0.001* |

| Diabetes duration (years) | – | 15.52 ± 3.00 | – |

| FPG (mg/dl) | 81.31 ± 5.92 | 182.84. ± 8.35 | <0.001* |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.35 ± 0.67 | 8.90 ± 1.59 | <0.001* |

BMI, body mass index; DR, diabetic retinopathy; f, female; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; m, male.

Data are expressed as mean ± SD.

Cell isolation and culture

PBMCs were prepared from heparinized blood by Ficoll-Hypaque density-gradient centrifugation. To study IL-17A production, PBMCs were stimulated with phytohaemagglutinin (5 µg/ml) at 2 × 106 cells/ml and 250 ng/ml ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) for 48 h at 37℃ in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

IL-17A concentrations in PBMCs and vitreous fluid from patients with T2DM and healthy controls were determined using the Human IL-17A Quantikine ELISA kit (BMS2017; eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA). All procedures were conducted at room temperature, and the mean absorbances of the standards and samples were determined from duplicates. The reaction was assayed at 450 nm using a Varioskan flash multifunction plate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Intracellular cytokine staining

PBMCs were stimulated with 20 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate and 1 µg/ml ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 6 h to detect IL-17-producing T cell frequencies in patients with DR. Brefeldin A (10 µg/ml; Sigma) was added to cultured PBMCs for 4 h. Stimulated PBMCs were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (137 mM sodium chloride, 2.7 mM potassium chloride, 10 mM disodium hydrogen phosphate, 2 mM potassium dihydrogen phosphate, pH 7.4) and incubated with phycoerythrin-Cy7-labeled anti-CD8 (eBioscience) and fluorescein-isothiocyanate-labelled anti-CD69 (eBioscience) or matched isotype (eBioscience) for 30 min in the dark at 4℃. PBMCs were then fixed in 4% formaldehyde, permeabilised with 0.1% saponin (Sigma) and stained with peridinin-chlorophyll-protein-labelled anti-CD3 (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA), phycoerythrin-labelled anti-IL-17 (eBioscience) or matched isotype control monoclonal antibody (eBioscience). Cells were analysed using a FACSCalibur and CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows version 19.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Group differences between patients with diabetes and controls were analysed using one-way analysis of variance or nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis tests, depending on normality assumptions and homogeneity of variances. Parameters with significant differences among all groups were further analysed using the Mann-Whitney U test or Student t test. Correlations among study parameters were analysed by Spearman’s correlation test. Graphs were prepared using Prism version 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). For all tests, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the study subjects are displayed in Table 1. No significant differences in age, and male to female ratio were observed between the control, non-DR and DR groups. Compared with the control and non-DR groups, subjects with DR had significantly higher BMIs, longer T2DM duration and elevated FPG and HbA1c levels (all P < 0.001, Table 1). Subjects with PDR had a significantly prolonged T2DM duration (P = 0.015) and elevated FPG (P < 0.001) and HbA1c (P = 0.003) levels compared with those of the NPDR group (Table 2). In patients that underwent vitrectomy, those with DR also had significantly higher BMIs (P < 0.001) and increased FPG (P < 0.001) and HbA1c (P < 0.001) concentrations compared with those of the control group (Table 3).

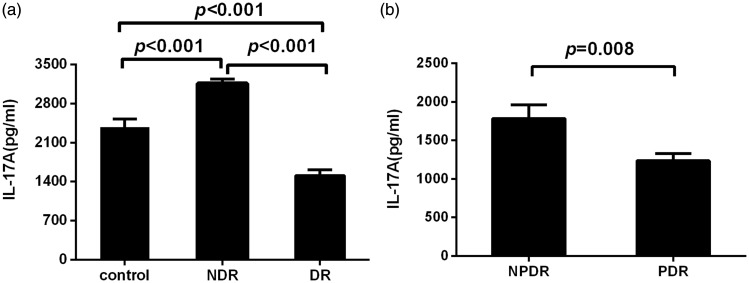

IL-17A concentrations in cultured PBMC supernatants

Low IL-17A concentrations were detected in unstimulated PBMC supernatants. After stimulation, IL-17A levels were significantly higher in patients with T2DM without DR than those in healthy controls (P < 0.001). In contrast, IL-17A concentrations were lower in patients with DR compared with those in healthy controls (P < 0.001, Figure 1(a)). IL-17A levels in the PDR group were significantly lower than those in the NPDR group (P = 0.008, Figure 1(b)).

Figure 1.

Interleukin (IL)-17A levels in stimulated cultured peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) supernatants measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). (a) IL-17A levels in PBMC supernatants from patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and no diabetic retinopathy (NDR) (n = 30), patients with diabetic retinopathy (DR) (n = 60) and healthy control subjects (n = 30). (b) IL-17A levels in PBMC supernatants from patients with nonproliferative DR (NPDR) (n = 30) and proliferative DR (PDR) (n = 30). PBMCs were cultured with phytohaemagglutinin (5 µg/ml) for 48 h. Data are represented as mean ± SD.

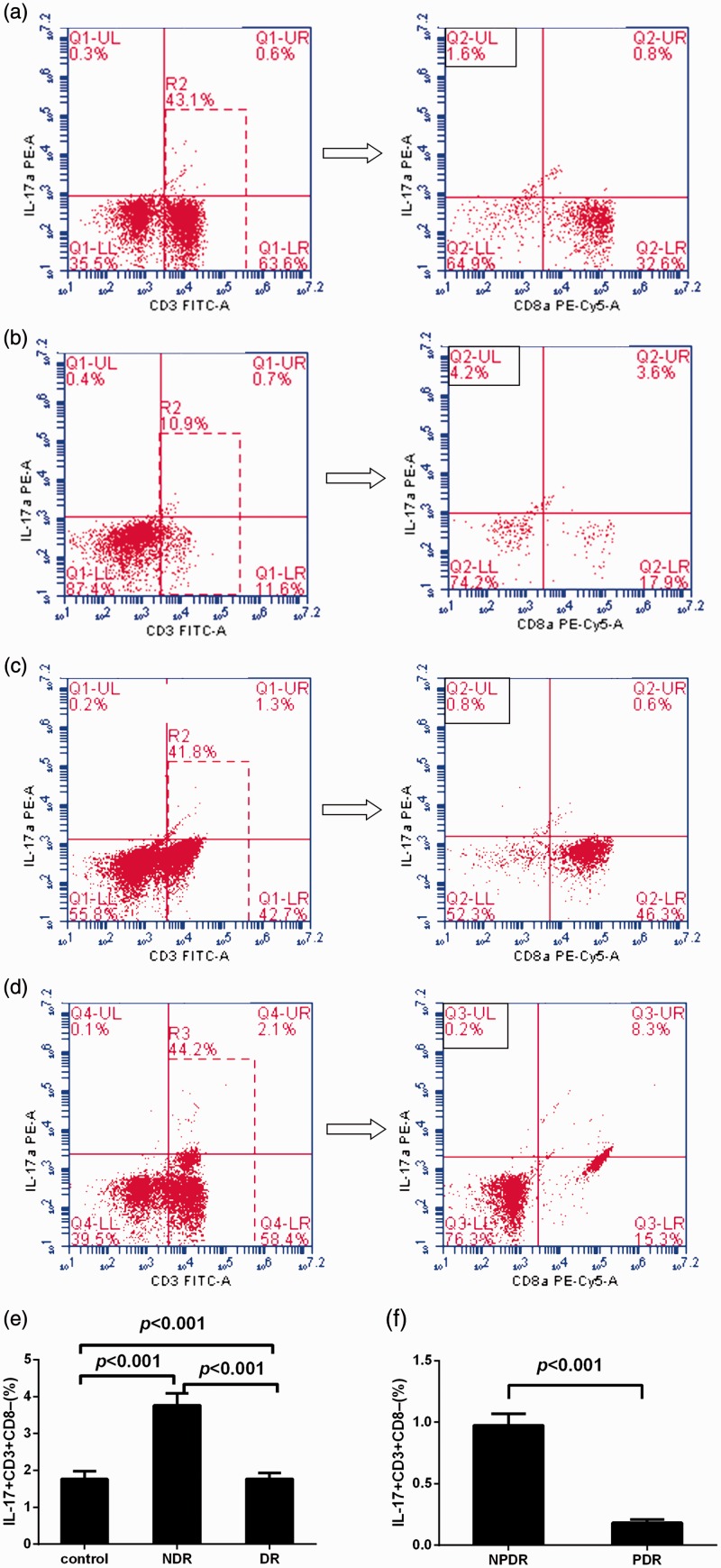

Th17 cell frequencies in PBMCs

Representative cytometric profiles of cytokine-positive Th17 cells from the DR, non-DR and healthy control groups are displayed in Figure 2. Compared with healthy controls (1.77 ± 1.18%), the percentage of peripheral Th17 cells was significantly increased in the non-DR patient group (3.76 ± 1.78%, P < 0.0001) and significantly decreased in the DR group (0.58 ± 0.55%, P < 0.0001). Compared with the NPDR group (0.98 ± 0.51%), Th17 cell frequency was significantly decreased in the PDR group (0.18 ± 0.13%, P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

(a–d) Representative flow-cytometric profiles of interleukin (IL)-17-producing CD3+CD8− T cells from patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with no diabetic retinopathy (NDR), nonproliferative DR (NPDR) and proliferative DR (PDR) and healthy control subjects. Percentages of the indicated cells are displayed in the quadrant areas. (e) Percentages of CD3+CD8− T cells with positive intracellular staining for IL-17 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from patients with NDR (n = 30), patients with DR (n = 60) and healthy control subjects (n = 30). (f) Percentages of CD3+ CD8− T cells with positive intracellular staining for IL-17 in PBMCs from patients with NPDR (n = 30) and PDR (n = 30).

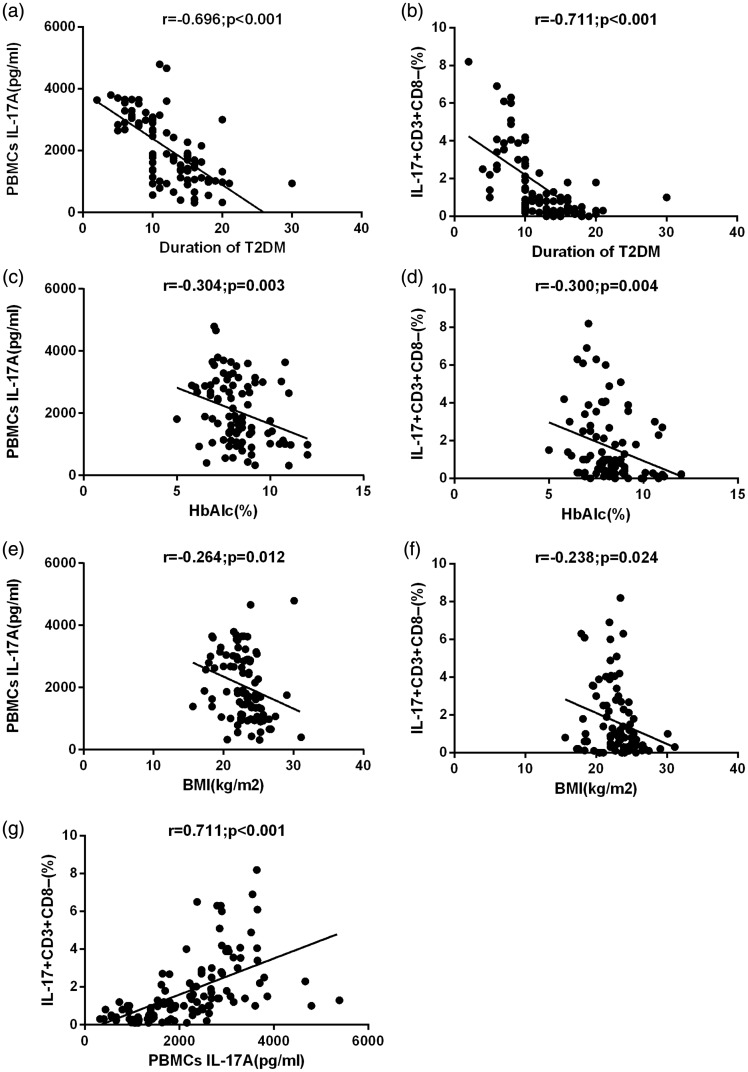

Correlation between PBMC cytokine profiles and disease phenotype

Spearman’s correlation analysis was performed to analyse the association between mean cytokine levels and various biochemical parameters. BMI, T2DM duration and HbA1c levels were negatively correlated with IL-17 concentrations (r = − 0.264, P = 0.012; r = −0.696, P < 0.001; r = −0.304; P = 0.003, respectively) and Th17 cell frequency (r = −0.238, P = 0.024; r = −0.711, P < 0.001; r = −0.300; P = 0.004, respectively) (Figure 3). IL-17 concentrations were positively correlated with Th17 cell frequency in all subjects (r = 0.711; P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

(a) Correlation between interleukin (IL)-17A concentrations in activated peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMCs) culture supernatants and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) duration. (b) Correlation between IL-17+CD3+CD8− T cells in PBMCs and T2DM duration. (c) Correlation between IL-17A concentrations in activated PBMC culture supernatants and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels in patients with T2DM. (d) Correlation between IL-17+CD3+CD8− T cells in PBMCs and HbA1c levels in patients with T2DM. (e) Correlation between IL-17A concentrations in activated PBMC culture supernatants and body mass index (BMI) in patients with T2DM. (f) Correlation between IL-17+CD3+CD8− T cells in PBMCs and BMI in patients with T2DM. (g) Correlation between IL-17A concentrations in activated PBMC culture supernatants and IL-17+CD3+CD8− T cells in PBMCs. Spearman correlation test was used (P < 0.05 significant) (r = correlation coefficient).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed using disease phenotype as the dependent variable and IL-17A levels as the independent variable. PBMC IL-17A levels and Th17 cell frequency displayed a significant positive association with T2DM [IL-17A: odds ratio (OR) = 1.001; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.000–1.002; P = 0.004; Th17: OR = 2.555; 95% CI = 1.471–4.438; P = 0.001] and a significant negative association with DR (IL-17A: OR = 0.998; 95% CI = 0.998–1.000; P < 0.001; Th17: OR = 0.071; 95% CI = 0.022–0.225; P < 0.001), even after adjusting for age and sex.

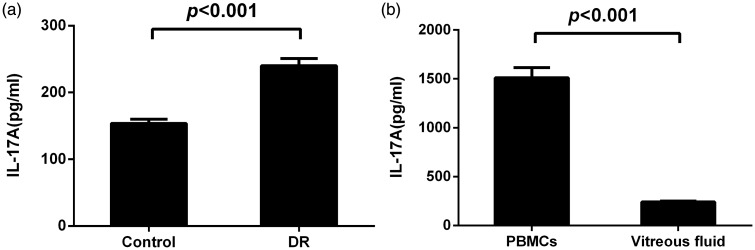

IL-17A concentrations in vitreous fluids

The DR group displayed significantly higher vitreous fluid IL-17A levels compared with those of the control group (P < 0.001) (Figure 4(a)). IL-17A levels in vitreous fluid were significantly higher than those in PBMCs from patients with DR (P < 0.001) (Figure 4(b)).

Figure 4.

(a) Interleukin (IL)-17A levels in the vitreous fluid measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). IL-17A levels were significantly higher in patients with DR than those in the control group (p < 0.001). (b) Vitreous fluid IL-17A levels were significantly higher than those in PBMCs in patients with DR (p < 0.001). Data are represented as mean ± SD.

Discussion

DM incidence has increased dramatically in recent decades. However, the pathogenesis of T2DM and its inflammatory complications, such as retinopathy, have yet to be established. It appears that immune function, and particularly T cells, plays an important role in the induction and exacerbation of T2DM and associated microvascular complications.

In this study, we examined the levels of circulating Th17 subsets in patients with T2DM with DR. We observed a significant decrease in the Th17 population, which was detected by cytokine production assays and Th17 cell frequency, in patients with T2DM with DR compared with that of healthy controls. The Th17 cell proportion and IL-17A concentrations in PBMCs were dramatically decreased as the disease progressed. However, vitreous fluid IL-17A levels in patients with DR were significantly higher than those in the control group. Our study suggests that Th17 immunity is involved in the systemic immune responses in patients with T2DM with DR.

IL-17A is an important cytokine implicated in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases.23,24 Recent findings have identified T2DM as a chronic inflammatory disease with changes in Th17 cell function. Shawn et al. determined that T cells from diet-induced obese mice expanded the Th17 cell pool and progressively increased IL-17A production in an IL-6-dependent process, compared with their lean littermates.25 This suggests that Th17 contributes to T2DM inflammation and insulin resistance. Sumarac-Dumanovic et al.24 demonstrated that the IL-23/IL-17A axis was stimulated in women with obesity, which is a primary risk factor for diabetes. Another recent study reported that patients with T2DM had higher PBMC IL-17A expression than that in healthy controls, indicating that T cells are skewed toward proinflammatory subsets that likely promote chronic inflammation through elevated cytokine production.20 In our previous study, although no significant difference in serum IL-17A levels was observed between patients with T2DM and healthy controls,19 serum IL-17A concentrations were relatively low, and serum cytokine levels are influenced by many factors. Thus, in the current study, we used PBMC cultures to evaluate IL-17 levels in patients with T2DM and healthy controls. Similarly, our study provided evidence that IL-17A levels and Th17 cells were both markedly increased in patients with T2DM without DR, supporting a role for Th17 immunity in systemic inflammation in T2DM. Thus, based on our study and previous reports, we infer that increased IL-17A production in T2DM patients without DR is part of the autoimmune process in T2DM.

An unexpected finding in our study was that low circulating IL-17A levels were observed in the DR group. Our results are consistent with a previous study on metabolic syndrome26 and with the study by Arababadi et al.27 in which serum IL-17A levels were significantly increased in patients with T2DM and decreased as the patients developed progressive end-stage nephropathy. This paradoxical pattern of change in IL-17A expression in patients with T2DM with or without DR remains elusive. However, there are several possible explanations. First, it may be attributed to impaired activation of the adaptive immune system in patients with T2DM with DR. A previous study revealed a reduced blood CD4+ lymphocyte count as the severity of DR increased.28 Decreasing CD4+ lymphocyte count is considered essential in the initiation and propagation of inflammation,29 leading to DR-associated damage to the retinal vasculature and retinal neovascularization.30 These findings suggest weakened cellular immunity in patients with DR. Second, patients with DR in our study had a long T2DM duration. Previous evidence has demonstrated a positive correlation between T2DM duration and DR risk.31,32 Therefore, Th17 cells in patients with T2DM with DR are indicative of impaired PBMCs. This is likely caused by two mechanisms: (1) an immunological abnormality of the disease itself that we mentioned above; and (2) chronic activation of the immune system related to the autoimmune process of T2DM, which may induce a diminished PBMC response to the stimulus. The deficiencies in PBMC activation and the immune response may contribute to the increased incidence of extracellular infections in patients with T2DM. Third, it is possible that most of the circulating IL-17A is excreted into the eyes in patients with DR. In the present study, vitreous fluid IL-17A levels in the DR group were higher than those in the control group. Additionally, we observed that IL-17A concentrations were higher in PBMCs than in vitreous fluid. Therefore, we hypothesize that intraocular IL-17A originated primarily from the circulation, and increased IL-17A levels contributed to DR development and progression. In summary, not only is DR an autoimmune disorder, but other etiological factors, such as environmental and genetic conditions, may also be involved in this complication. Future studies to determine the mechanistic processes underlying this phenomenon are warranted.

Conclusions

Our study revealed significant differences in Th17 levels between patients with T2DM with DR and healthy controls. The decrease in Th17 cell frequency and circulating IL-17A concentrations and the increase in vitreous fluid IL-17A levels are possibly associated with the pathogenesis of T2DM with DR, which is a multifactorial disorder involved in various physiological and pathological conditions. The causal role of Th17 immunity and the cellular mechanisms underlying DR pathogenesis remain to be elucidated.

Acknowledgements

The Authors wish to thank all participants of this study.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was supported by the Fund for National Natural Science Foundation (81300784).

References

- 1.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, et al. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 1047–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramachandran A, Ma RC, Snehalatha C. Diabetes in Asia. Lancet 2010; 375: 408–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tilg H, Moschen AR. Inflammatory mechanisms in the regulation of insulin resistance. Mol Med 2008; 14: 222–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spranger J, Kroke A, Möhlig M, et al. Inflammatory cytokines and the risk to develop type 2 diabetes: results of the prospective population-based European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Potsdam Study. Diabetes 2003; 52: 812–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grimble RF. Inflammatory status and insulin resistance. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2002; 5: 551–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pickup JC. Inflammation and activated innate immunity in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes care 2004; 27: 813–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pickup JC, Crook MA. Is type II diabetes mellitus a disease of the innate immune system? Diabetologia 1998; 41: 1241–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fong DS, Aiello L, Gardner TW, et al. Retinopathy in diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004; 27(Suppl 1): S84–S87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Funatsu H, Yamashita H, Noma H, et al. Aqueous humor levels of cytokines are related to vitreous levels and progression of diabetic retinopathy in diabetic patients. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2005; 243: 3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demircan N, Safran BG, Soylu M, et al. Determination of vitreous interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) levels in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Eye(Lond) 2006; 20: 1366–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuuki T, Kanda T, Kimura Y, et al. Inflammatory cytokines in vitreous fluid and serum of patients with diabetic vitreoretinopathy. J Diabetes Complications 2001; 15: 257–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abu El-Asrar AM, Struyf S, Kangave D, et al. Chemokines in proliferative diabetic retinopathy and proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Eur Cytokine Netw 2006; 17: 155–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hernández C, Segura RM, Fonollosa A, et al. Interleukin-8, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and IL-10 in the vitreous fluid of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Diabet Med 2005; 22: 719–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitamura Y, Takeuchi S, Matsuda A, et al. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 in the vitreous of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmologica 2001; 215: 415–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adamis AP, Miller JW, Bernal MT, et al. Increased vascular endothelial growth factor levels in the vitreous of eyes with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 1994; 118: 445–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baudouin C, Fredj-Reygrobellet D, Brignole F, et al. MHC class II antigen expression by ocular cells in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 1993; 7: 523–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Attawia MA, Nayak RC. Circulating antipericyte autoantibodies in diabetic retinopathy. Retina 1999; 19: 390–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang S, Le-Ruppert KC. Activated T lymphocytes in epiretinal membranes from eyes of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1995; 233: 21–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen H, Wen F, Zhang X, et al. Expression of T-helper-associated cytokines in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with retinopathy. Mol Vis 2012; 18: 219–226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jagannathan-Bogdan M, McDonnell ME, Shin H, et al. Elevated proinflammatory cytokine production by a skewed T cell compartment requires monocytes and promotes inflammation in type 2 diabetes. J Immunol 2011; 186: 1162–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Clasification of Diabetes Mellitus. American Diabetes Association: clinical practice recommendations 2002. Diabetes Care 2002; 25(Suppl 1): S1–S147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilkinson CP, Ferris FL, 3rd, Klein RE, et al. Proposed international clinical diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema disease severity scales. Ophthalmology 2003; 110: 1677–1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miljkovic D, Cvetkovic I, Momcilovic M, et al. Interleukin-17 stimulates inducible nitric oxide synthase-dependent toxicity in mouse beta cells. Cell Mol Life Sci 2005; 62: 2658–2668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sumarac-Dumanovic M, Stevanovic D, Ljubic A, et al. Increased activity of interleukin-23/interleukin-17 proinflammatory axis in obese women. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009; 33: 151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winer S, Paltser G, Chan Y, et al. Obesity predisposes to Th17 bias. Eur J Immunol 2009; 39: 2629–2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Surendar J, Aravindhan V, Rao MM, et al. Decreased serum interleukin-17 and increased transforming growth factor-β levels in subjects with metabolic syndrome (Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study-95). Metabolism 2011; 60: 586–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arababadi MK, Nosratabadi R, Hassanshahi G, et al. Nephropathic complication of type-2 diabetes is following pattern of autoimmune diseases? Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010; 87: 33–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Obulkasim M, Turdi A, Amat N, et al. Neuroendocrine-immune disorder in type 2 diabetic patients with retinopathy. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2011; 38: 229–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishimura S, Manabe I, Nagasaki M, et al. CD8+ effector T cells contribute to macrophage recruitment and adipose tissue inflammation in obesity. Nat Med 2009; 15: 914–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adamis AP, Berman AJ. Immunological mechanisms in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Semin Immunopathol 2008; 30: 65–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tapp RJ, Shaw JE, Harper CA, et al. The prevalence of and factors associated with diabetic retinopathy in the Australian population. Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 1731–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kazemi Arababadi M. Interleukin-4 gene polymorphisms in type 2 diabetic patients with nephropathy. Iran J Kidney Dis 2010; 4: 302–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]