INTRODUCTION

The histiocytoses are a diverse group of disorders defined by the pathologic infiltration of normal tissues by cells of the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS). Due to biologic variability of the cells of the MPS and the tissues they inhabit, histiocytic disorders are one of the most intriguing yet complex areas of modern hematology and can be tremendously difficult to diagnose. Until recently, the mechanisms of pathogenesis of the histiocytoses have been speculative and debate has focused on classification of these conditions as reactive versus neoplastic. However, starting 6 years ago, a series of recurrent, activating mutations in genes encoding kinases of the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase system have been discovered in a large proportion of histiocytosis patients. These discoveries have resulted in potently effective therapies in genetically defined subsets of adults with these disorders. Here, we review the recent molecular advances in the systemic histiocytoses and their impact on the treatment.

SYSTEMIC HISTIOCYTIC NEOPLASMS AND THEIR CURRENT CLASSIFICATION

According to the fourth edition of the World Health Organization classification, histiocytic disorders can be classified into two main categories based on the phenotype of cells present within the lesions: 1) Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), and 2) non-Langerhans cell histiocytoses (non-LCH) (Figure 1A). LCH received its name as the tumoral cells share unique ultrastructural features of normal Langerhans cells (LCs). However, comparisons of gene expression between LCH cells and LCs indicate that LCH cells are considerable less mature than LCs and are phenotypically closer to myeloid DCs as they are to LCs [1] [2]. These data question LCs as the cell-of-origin of LCH, a hypothesis that has largely been discarded in recent years in favor of the idea that LCH arises from either myeloid DCs, their progenitors, or cells even prior to DC, monocyte, or macrophage differentiation [3].

Figure 1. Characteristic histology of histiocytic lesions.

Classification schema for the histiocytoses based on (A) the 2008 WHO Classification [4] and (B) a recently updated 2016 classification system from the Histiocyte Society [5]. (C) Diagnostic biopsy specimens of Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD), juvenile xanthogranulomatous disease (JXG), and Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD) lesions stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The JXG biopsy demonstrates characteristic xanthomatous histiocytes along with multinucleated Touton giant cells. The ECD biopsy shows characteristic infiltration of foamy histiocytes. The LCH biopsy demonstrates characteristic clusters of histiocytes with reniform nuclei and the background inflammatory infiltrate is rich from eosinophils. The RDD biopsy demonstrates characteristic large histiocytes with emperipolesis. (D) Diagnostic biopsy specimen for indeterminate cell histiocytosis. H&E stain showing diffuse infiltration by a histiocytic-appearing neoplasm that is indistinguishable from a histiocytic sarcoma by conventional histopathology. Multinucleated cells are seen. The lesion is positive for CD1a and negative for CD163 (reactive histiocytes show positive staining) and Langerin. By definition, neoplastic cells lack Birbeck granules on ultrastructural examination (not shown).

In the WHO classification system, LC lesions are divided into two sub-groups based on the degree of cytologic atypia and clinical aggressiveness: LCH and Langerhans cell sarcoma. In contrast, non-LCH are a heterogenous group of disorders including Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD), juvenile xanthogranulomatous disease (JXG), Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), histiocytic sarcoma (HS), indeterminate cell histiocytosis (ICH), and others defined by the accumulation of histiocytes that do not meet the diagnostic criteria for LCH, LC sarcoma, or hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) (Figure 1A) [4].

In addition to the WHO Classification, the Histiocyte Society has recently proposed a new classification of histiocytosis incorporating clinicopathologic, prognostic, and new genetic findings which have not been accounted for in the WHO Classification. This new classification system categorizes the histiocytoses into 5 groups: "L" (Langerhans), "C" (cutaneous and mucocutaneous), "M" (malignant), "R" (Rosai-Dorfman), and "H" (hemophagocytic) groups [5] (Figure 1B). One important motivation of this effort to regroup the histiocytoses was to take into considerable new molecular genetic information which has revealed the unexpected genetic similarity between LCH and the non-LCH neoplasms (Figure 1C and Figure 1D). Thus, in the revised Histiocyte Society classification, the L group includes LCH and ECD, entities which share mutations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway in >80% of cases [6] [7] and may coexist together [8]. This review will focus on the biological and therapeutic importance of MAPK mutations in diseases within this L category. The pathophysiology of hemophagocytic disorders of the H group appear to be distinct from those of the L group disorders and the conditions within the C, M, and R groups do not have clearly defined molecular characteristics of pathophysiology currently.

DISCOVERY OF B-RAF PROTO-ONCOGENE MUTATIONS IN HISTIOCYTOSES

In 2010, Badalian-Very et al. identified that 57% of LCH patients carry the BRAFV600E mutation, thereby identifying a clonal marker of the disease and suggesting that LCH is driven by activation of the MAP kinase pathway [6]. This high frequency of BRAFV600E mutations was then validated in a subsequent study in LCH [7] and also found in a significant proportion of patients with non-LCH disorders including ~50% of patients with ECD [7] as well as patients with HS [9]. In contrast to recurrent BRAFV600E mutations, activating point mutations in BRAF other than V600E have been found only rarely in histiocytoses. These include BRAFV600D in LCH [10] [11], BRAFF595L in histiocytic sarcoma [12], and BRAF V600insDLAT in LCH [13]. In a recently published study, whole exome sequencing (WES) and targeted BRAF sequencing studies in 24 LCH patient samples lacking BRAFV600E mutations identified in-frame BRAF deletions in the β3-αC loop of BRAF in ~6% of LCH patients [14]. This finding identifies BRAF deletions as the third most common MAPK pathway alteration in LCH. Importantly, unlike BRAFV600E mutant cells, cells bearing BRAF in-frame deletions were resistant to the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib [14], suggesting a unique biochemical mechanism of ERK activation mediated by different mutations in BRAF. Similar ERK-activating, in-frame BRAF deletions have also recently been described in other malignancies including melanoma and ovarian cancers [15] [16] [17]

DISCOVERY OF ADDITIONAL KINASE ALTERATIONS IN HISTIOCYTOSES

A-RAF Proto-oncogene

Following the discovery of BRAFV600E mutations in LCH, the consistent identification of phospho-ERK positivity in neoplastic histiocytes in LCH and non-LCH patients regardless of BRAFV600E mutational status resulted in an effort to identify additional mutations activating ERK in these orders [6] [18] [19]. A surprising outcome of one whole-exome analysis was the discovery of an activating mutation in ARAF, an additional RAF kinase, in LCH [20]. ARAF mutations have subsequently also been found to be recurrent in non-LCH and are present in 21% of ECD and 12.5% of RDD patients [21]. Although BRAFV600E mutations have not been identified in JXG, 18% of JXG cases have been found to have an ARAF mutation. However, these activating ARAF mutations were found to co-occur with activating NRAS mutations in those cases [21], suggesting that either ARAF mutations may occur subclonally in histiocytosis or that they may require additional cooperating activating mutations to drive histiocytosis.

Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase Kinase 1

Continued genomic analyses of LCH and non-LCH have identified activating mutations in mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 (MAP2K1) as among the most common mutations in the BRAFV600-wildtype LCH and non-LCH patients. MAP2K1 encodes MEK1, the kinase just downstream of the RAF kinases. MAP2K1 mutations are found only in patients wildtype for BRAFV600E, consistent with their convergent effects on activation of the MAPK pathway [19] [22] [21]. The true prevalence of MAP2K1 mutations in LCH and ECD is uncertain at present because their frequency differs substantially among the samples tested in various reports which are in between 10 to 40% [19] [22] [21]. Recently, a MAP2K1F53L mutation was identified in an HS lesion, which was possibly transdifferentiated from a follicular lymphoma (as supported by the fact that both lesions harbored a BCL2 gene rearrangement). In this case, the MAP2K1 mutation was specific to the HS and not present in the follicular lymphoma, suggesting that the MAP2K1 mutation may specifically drive the histiocytosis phenotype [23].

Ras Isoforms

As with other hematological malignancies, recurrent mutations in N/KRAS but not in HRAS have been found in systemic histiocytoses. This includes NRAS mutations in 3–7% of ECD and NRAS and KRAS mutations in 18% of JXG patients, respectively [24] [21]. However, RAS mutations frequently coexist with activating ARAF mutations in JXG, as discussed above. Similarly, NRAS and KRAS mutations are present in 12.5% and 25% of RDD patients, respectively [21]. The sole exception to the lack of HRAS mutations in histiocytosis has been the report of an HRAS mutation in a HS with a concomitant BRAFF595L mutation [12]. In contrast to non-LCH, rare RAS mutations have been reported in LCH patients in the setting of concomitant juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia [25] and have not been reported in patients with LCH alone. Although this is a genomic abnormality characteristic of JMML, upregulation of ERK signaling through NRAS activation also appears to drive LCH based on human genetic data as well as mouse model phenotypes where the NRASG12D mutation is expressed in hematopoietic cells [26].

Phosphoinositide 3-kinases isoforms

Consistent with potential activation of the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway downstream of RAS mutations in non-LCH, PIK3CA mutations have been described in 17% of BRAF-wildtype ECD patients [21]. These mutations cluster in the α-helical and kinase domains of PIK3CA [24] [21] as have been reported in other forms of cancer. Similar to the rarity of RAS mutations in LCH, activating mutations in PIK3CA have only been identified in 1.2% of LCH patients [11] [27]. In addition to PIK3CA mutations, rare PI3KD mutations have been identified in JXG [19]. In contrast to the consistent role of ERK activation in the histiocytosies, the expression of PI3K isoforms and the role of constitutive PI3K-AKT signaling need to be further evaluated in the pathogenesis of the histiocytoses.

Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase Kinase Kinase 1

In the course of performing WES on LCH lesions, Nelson et al. also discovered two somatic mutations in mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase (MAP3K1), which encodes MEKKK1, an enzyme with both E3 ubiquitin ligase activity as well as serine/threonine kinase activity [22]. Both mutations identified in MAP3K1 in LCH are frameshift deletions leading to truncated proteins (MAP3K1T799fs and L1481fs). However, the effects of these mutations on ERK activation are still unclear.

GENE FUSIONS

In addition to single nucletoide variants and small insertion/deletion mutations, structural alterations and gene fusions represent important somatic alterations driving the pathogenesis of common cancers. However, no gene fusions had been uncovered in histiocytic neoplasms until 2015 when two studies described gene fusions in BRAFV600E-wildtype, non-LCH neoplasms [21] [28]. In addition to BRAF mutations, fusions involving BRAF have been identified in non-LCH. These include an RNF11-BRAF fusion in JXG and a CLIP2-BRAF fusion in a patient with a non-LCH resembling HS. In both cases, exons 11–18 of BRAF were involved in the fusion, leading to loss of the N-terminal regulatory, RAS-binding domain of BRAF with placement of the intact BRAF kinase domain under the aberrant regulation of another promoter. It is not clear what role, if any, the N-terminal fusion partner to BRAF may play in these cases. In a recently published paper, Chakraborty et al. identified another BRAF fusion event involving FAM73A (MIGA1) on chromosome 1p31.1 and BRAF (located on chromosome 7q34) in LCH. The chimeric FAM73A-BRAF gene was predicted to result in an in-frame protein lacking the autoinhibitory domain of BRAF (exons 1–8) but retaining an intact kinase domain as has been observed for other known BRAF fusion genes [29].

In addition to BRAF fusions, fusions involving ALK have been described in two ECD patients, both kinesin family member 5B (KIF5B)-ALK fusions. In both cases, the N-terminal coiled-coil domain of KIF5B was fused to the intact kinase domain of ALK resulting in inappropriate expression and constitutive activation of ALK [21]. KIF5B serves as a microtubule-dependent motor involved in the normal distribution of mitochondria and lysosomes, whereas ALK encodes a neuronal orphan receptor tyrosine kinase whose expression is normally limited to the nervous system. KIF5B-ALK fusions, therefore, result in inappropriate ALK expression and constitutive activation of the MAPK and PI3K-AKT pathways within histiocytes. Similarly, an EML4-ALK rearrangement was also more recently described in the lesional biopsy of an adolescent patient with histiocytosis not otherwise specified (NOS) [30]. Both the KIF5B-ALK and EML4-ALK fusions have similar configurations to those previously described in non-small-cell lung cancer [31, 32] and are functionally activating kinase fusions that show sensitivity to ALK inhibition in vitro.

Thus far, fusions of neurotrophic tyrosine kinase member (neurotrophic tyrosine kinase, receptor type 1 (NTRK1)) have been described in two cases of histiocytic neoplasms. In the first case, the lesional biopsy from an ECD patient was confirmed to lead to fusion of the N-terminal coiled-coil domain of Lamin A/C (LMNA) to the intact kinase domain of NTRK1 resulting in inappropriate expression and constitutive activation of NTRK1 [21]. LMNA encodes a component of the nuclear lamina, a fibrous layer on the inner nuclear membrane that provides a framework for the nuclear envelope. NTRK1 encodes the TrkA receptor tyrosine kinase, which is a membrane-bound receptor that phosphorylates itself and members of the MAPK pathway leading to cellular proliferation and differentiation. More recently, a TPR-NTRK1 fusion was detected in an adult patient with histiocytosis NOS. Both kinase fusions including LMNA-NTRK1 and TPR-NTRK1 result in inappropriate expression of NTRK1 with consequent constitutive activation of MAPK and PI3K-AKT pathways within histiocytes. These fusions have similar configurations to previously described LMNA-NTRK1 fusions in spitzoid neoplasms [33] and TPR-NTRK1 fusions in lipofibromatosis-like neural tumors [34]. Whether these fusions in ALK or NTRK1 in histiocytosis results in clinical sensitivity to ALK and NTRK inhibitors, respectively, will be important to determine in the near future.

In addition to activating kinase fusions, recurrent Ets variant 3-nuclear receptor coactivator 2 fusions (ETV3-NCOA2) fusions have now been described in ICH [28]. This fusion juxtaposes the N-terminal ETS domain of ETV3, a winged helix-turn-helix DNA-binding domain [28] [35] [36], to the C-terminal transcriptional activation domains transcriptional activation domain 1 (AD1), CBP/p300 interaction domain (CID), and transcriptional activation domain 2 (AD2) of NCOA2. This configuration is consistent with previously described NCOA2 fusions in cancer [28] [35] [37] [38] [39] [40]. Previous studies of NCOA2 fusions have demonstrated that the AD1 and CID domains are required for transformation of NCOA2 fusion proteins [35] [38] [40]. The involvement of the same NCOA2 C-terminal domains and the evidence that the AD1 and CID domains are necessary for NCOA2 fusion protein transformation supports a model where the NCOA2 C-terminal transcriptional activation domains are aberrantly targeted by the DNA-binding domain provided by an N-terminal fusion partner [28] [35] [37] [38] [39] [40]. It is not yet clear how the ETV3-NCOA2 fusion relates to the persistent MAPK activation known to be present in ICH patients. Further functional characterization of the ETV3-NCOA2 fusion in the pathogenesis of histiocytic neoplasms is therefore needed.

THERAPEUTIC EFFICACY OF KINASE INHIBITOR THERAPY IN HISTIOCYTOSES

The above described molecular advances have led to the advent of clinical studies and trials of targeted molecular therapeutics for patients with histiocytosis described below (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Clinical studies and trials of targeted agents for the treatment of histiocytic neoplasms

| Clinical Studies and Trials |

Therapeutic agent | Mechanism of Action |

Patient Population | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haroche et al. 2015 [43] | Vemurafenib | RAF inhibitor | Eight adult patients with severe, treatment refractory BRAF-mutant ECD or ECD/LCH hybrid disease. | All patients had a significant and sustained clinical response as measured by positron emission tomography scanning during a 6–16-month follow-up period (mean 10.5-month). |

| Hyman et al. 2015 [41] | Vemurafenib | RAF inhibitor | Phase II clinical trial with 18 adults with BRAF-mutant ECD or LCH | 43% response rate with 86% of patients showing disease regression. No progression while on treatment (0.6–18.6 months, median 5.9 months). |

| Gianfreda et al. 2015 [51] | Sirolimus | m-TOR inhibitor | Open-label trial of 10 patients with ECD | 8/10 patients had objective responses or disease stabilization, whereas 2/10 patients had disease progression. |

| Diamond et al. 2016 [21] | Trametinib and Cobimetinib | MEK inhibitors | Two adult ECD patients | Dramatic radiologic improvements, as well as clinical improvements. Both patients have been sustained for nearly 6 months. |

| Aubart et al. 2016 [46] | Cobimetinib | MEK inhibitor | Three BRAF-wildtype ECD patients refractory to conventional therapy | All patients had a sustained metabolic response (Follow-up: 5–22 months). |

| Lee et al. 2017 [30] | Trametinib | MEK inhibitor | One adult LCH patient with a BRAF inframe-deletion (BRAFN486_P490del) | Dramatic response within 5 days of initiating treatment. Follow-up PET-CT showed complete resolution of lesions. |

| NCT01677741 | Dabrafenib | RAF inhibitor | Ongoing phase I/II trial in children with LCH | One child with refractory LCH treated with oral dabrafenib, continued to show stable disease at week 16. |

| NCT02124772 | Trametinib in combination with Dabrafenib | RAF and MEK inhibitors | Children and adolescents with BRAFV600E-mutant diseases including LCH | - |

| NCT02649972 | Cobimetinib | MEK inhibitor | Open-label, single-center, phase II trial for adults with ECD, RDD, ECD/RDD hybrid, LCH with BRAF-wildtype histiocytosis or BRAFV600E-mutated histiocytosis intolerant of or without access to BRAF inhibitor therapy | Preliminary results demonstrated robust efficacy [49]. Twenty percent of patients showed a complete metabolic response and 80% a partial metabolic response. |

| NCT02281760A | Dabrafenib and Trametinib | RAF and MEK inhibitors | Phase II, open-label trial of dabrafenib and trametinib in adult ECD patients with BRAFV600E-mutant lesion | - |

Abbreviations: ECD, Erdheim-Chester Disease; LCH: Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis; RDD: Rosai-Dorfman Disease

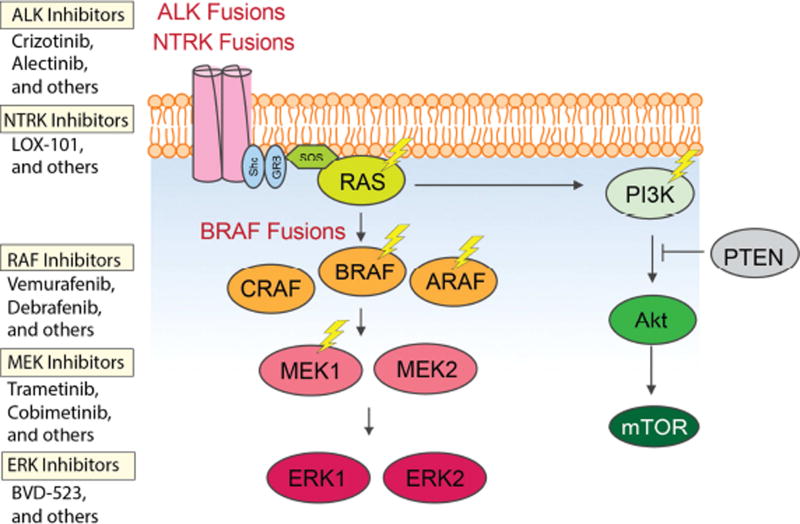

Figure 2. Activating mutations driving kinase signaling in histiocytic neoplasms.

Approximately 50% of patients with Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis and non-LCH neoplasms have a BRAFV600E mutation. This is closely followed by mutations in MAP2K1 (encoding MEK1). Non-LCH patients also have a high frequency of ARAF and N/KRAS mutations which are present at lower frequencies in LCH patients. Mutations in BRAF outside of V600 residue as well as fusions of BRAF, ALK, and NTRK1 are also known to occur in LCH and non-LCH. Finally, rare activating mutations in PIK3CA are known to occur in LCH and non-LCH. Thus far, there are clinical data supporting the use of RAF inhibitors for BRAFV600E mutant histiocytosis and preliminary data to support the use of MEK inhibitors in the use of BRAFV600 wildtype histiocytosis. There are no published data regarding the use of ALK, NTRK, or ERK inhibitors in patients with histiocytic disorders.

RAF Inhibitors

Clinical experience with the use of BRAF inhibitors for BRAFV600E mutant solid tumors motivated use of these same agents for patients with histiocytosis shortly after their discovery. Thus far, the only prospective clinical trial of RAF inhibitors in histiocytosis occurred as part of a histology-independent "basket" study utilizing the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib for patients with BRAFV600E mutant cancers of several different histologic types. In this study, a combined cohort of 22 ECD and 4 LCH patients experienced a response rate of 64% to vemurafenib [41]. Moreover, extended follow-up of this study presented at the 2016 ASH meeting has identified that these responses are durable with a median treatment duration now of 14.9 months (range: 2–43 months) [42]. In addition to this clinical trial, a prospective case series by Haroche et al. has reported favorable responses to vemurafenib in 8 adult patients with severe, treatment refractory, BRAFV600E-mutant ECD or ECD/LCH mixed histiocytosis [43]. All patients in this study had a significant and sustained clinical response as measured by positron emission tomography (PET) scanning at a median of 10 months (range, 10–16 months).

In contrast to the results of vemurafenib treatment in adults with histiocytosis, there is only a single report of a child with histiocytosis treated with vemurafenib. In this case, an 8 month old with BRAF-mutated, high-risk LCH, whose disease failed to respond to multiple rounds of prior therapy, experienced dramatic clinical efficacy to vemurafenib with a sustained response during the 10-month follow-up period [27]. Pediatric formulations are being developed, and phase I/II trials are ongoing in pediatrics with LCH for the first generation BRAF inhibitor, dabrafenib (NCT01677741). Preliminary results describe two children with refractory LCH treated with dabrafenib, one of whom had stable disease at week 16 [44].

While the development of acquired resistance as well as de novo resistance to vemurafenib is commonly observed in BRAFV600E-mutant melanoma and other cancers, to date RAF inhibitor resistance has been described in only a single patient with BRAFV600E-mutant histiocytosis [45]. In this case a patient with BRAFV600E-mutant ECD without evidence of MAP2K1 or N/KRAS mutations at diagnosis developed acquired dabrafenib resistance coincident with identification of a KRASQ61H-mutant/BRAFV600E-wildtype ECD lesion at clinical relapse. These lesions further regressed with addition of the MEK inhibitior trametinib to dabrafenib [45]. Notably, a phase II therapeutic trial of the use of dabrafenib, a BRAFV600E inhibitor, and trametinib, an inhibitor of MEK, in ECD patients with BRAFV600E mutation positive lesions is ongoing (NCT02281760).

MEK Inhibitors

The efficacy of MEK inhibitors for histiocytosis was first reported in two non-LCH patients with MAP2K1K57N and MAP2K1Q56P mutations treated with trametinib and cobimetinib, respectively [21]. Both patients experienced dramatic radiologic improvements, as well as clinical improvements, and both have been sustained for nearly 6 months. Cohen-Aubart et al. also reported their retrospective results of cobimetinib used in monotherapy for three BRAF-wildtype patients with ECD. The three patients had a sustained metabolic response, and response was assessed with PET scan and also confirmed by decrease of creatinine and C-reactive protein levels and/or magnetic resonance imaging [46]. Although 2 of the 3 patients in this study had a MAP2K1 mutation, the exact mutation was not noted however. This important as some mutations in MAP2K1 mutations have been reported as resistant MEK inhibition [47]. Recently, Azorsa et al. reported a patient with treatment refractory LCH and identified a novel mutation in the MAP2K1 gene (MAP2K1 c.293_310del mutation), which leads to p-ERK activation [48]. This mutation was found to be non-responsive to MEK inhibitor in vitro as well as in vivo as the patient progressed under trametinib treatment [48]. These findings emphasize the importance of functional assessment of genomic data in assigning treatment for patients. In another recent study, an adult LCH patient with FDG-PET lesions in the neck and groin declined systemic chemotherapy owing to concerns regarding its impact on her quality of life [30]. Targeted sequencing of a biopsy from the neck lesion revealed a BRAF inframe-deletion (N486_P490del) with a VAF of 14%. Experimental evidence indicated that akin to BRAFV600E, this mutation also results in constitutive activation of downstream signaling but insensitive to V600E-specific inhibitors. Thus, trametinib was started and within 5 days of initiating treatment, her neck and groin tumors disappeared. Follow-up PET-CT showed her lesions had completely resolved [30].

In order to determine the therapeutic efficacy of single-agent MEK inhibition in histiocytosis in a prospective fashion, a phase II trial of single-agent cobimetinib for adults with histiocytic disorders is currently ongoing (NCT02649972). This is an open-label, single-center study exploring the efficacy and safety of single-agent cobimetinib in patients with histiocytic disorders whose tumors are BRAFV600-wildtype or BRAFV600E-mutant and are intolerant to, or unable to access, BRAF inhibitors. Preliminary results demonstrated robust efficacy of single-agent cobimetinib in 7/7 patients with BRAF-wildtype ECD, RDD, and LCH on this trial with 20% of patients showing a complete metabolic response and 80% a partial metabolic response. Metabolic response was evaluated by 18F-FDG PET scan performed every two cycles [49] as is commonly performed to radiographically evaluate lesions in histiocytosis patients.

The MEK inhibitor cobimetinib has been evaluated in association with vemurafenib in metastatic melanoma and treatment with both a RAF inhibitor and a MEK1 inhibitor, such as trametinib, may prevent the appearance of resistance [50]. Such a trial of trametinib in combination with dabrafenib in children and adolescents with BRAFV600E mutation-positive diseases including LCH has been started (NCT02124772).

Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) Inhibitors

In addition to targeting the MAPK pathway, the inflammatory-neoplastic nature of ECD and previously described PIK3CA mutations leading to mTOR pathway activation in 11% of ECD patients [24] has led to efforts to inhibit PI3K signaling in histiocytosis. To this end, a 10-patient trial of the mTOR inhibitor sirolimus and prednisone was recently reported [51]. Eight patients achieved stable disease or objective responses, whereas 2 had disease progression. Treatment was continued at least 24 months in patients who showed disease stabilization or improvement. Although responses were far less dramatic than those observed in BRAF-mutated ECD patients receiving vemurafenib, the therapeutic efficacy of sirolimus and steroids in this trial was not negligible. Moreover, none of the patients in this series harbored PIK3CA gain-of-function mutations, suggesting the need to focus PI3K inhibition on the subset of ECD patients that actually carry activating mutations in this pathway [51].

SUMMARY

As described above, mutations activating kinase signaling can now be identified in the majority of patients with LCH and ECD. Although histiocytoses are classified under lymphoid neoplasms in the most recently proposed 2016 WHO classification [52], increasing gene expression and functional analyses of these disorders suggest that histiocytic neoplasms are closer to the myeloid origin than lymphoid. Thus, reconsideration of the placement of these conditions within the rubric of the 2016 revision of WHO classification is needed. Moreover, discovery of these mutations has led to important therapeutic advances for adults with histiocytosis. Nonetheless, a number of important biological, genetic, and therapeutic questions remain for patients with histiocytoses. First, the precise cell-of-origin of LCH and ECD remain to be clarified further. While recent data suggest that BRAFV600E mutations may be detected in CD34+ cells in patients with LCH, functional evidence of the disease-initiating capacity of these cells remains to be demonstrated in xenograft studies. Moreover, the cell-of-origin of non-LCH neoplasms have not been investigated.

From a molecular level, the sustained progress that has been made thus far in understanding the molecular underpinnings of LCH and ECD would now be further propelled by genetic studies focused on specific histologic subsets of histiocytoses such as HS and JXG. Such studies are now needed to better describe, classify, and ultimately treat these forms of histiocytoses whose pathogenesis may differ from that of the more common subtypes. Furthermore, we still do not know the frequency of kinase fusions in patients with histiocytosis. Greater systematic use of RNA-seq analysis to identify fusions will therefore be important moving forward. In addition, the landscape of potentially recurrent genetic events cooperating with kinase mutations in histiocytosis remains to be defined.

Finally, in terms of therapeutic advances, the demonstration of the efficacy of single-agent RAF inhibition as well as preliminary evidence of the efficacy of single-agent MEK inhibition in adults with BRAFV600E-mutant histiocytic neoplasms has led to questions of whether RAF, MEK, or combined RAF plus MEK inhibition should be recommended for initial therapy. For those patients lacking the BRAFV600E mutation, prospective clinical trial data regarding the utility of MEK inhibition is awaited. Moreover, with the application of technology for accurate detection and serial tracking of genetic alterations in plasma cell-free DNA, mutational analysis for histiocytosis-associated somatic mutations in plasma and urine will be very helpful for less invasive and more frequent monitoring of disease activity in patients with ECD/LCH [53]. Finally, further data about the utility and safety of targeted therapy against RAF and MEK are needed to make decisions for those children with LCH who are relapsed or refractory to convention, non-targeted therapy.

Key Points.

-

-

Nearly every Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis and Erdheim-Chester Disease patient has ERK activation due to activating mutations in ARAF, BRAF, MEK1/2, or N/KRAS, or kinase fusions.

-

-

BRAF inhibition results in dramatic and durable responses in patients with BRAFV600E mutant histiocytosis.

-

-

MEK inhibitors may be efficacious for treating BRAF-wildtype histiocytosis.

-

-

The safety and therapeutic utility of targeted therapy versus conventional therapy for children with Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis remains to be determined.

-

-

Further genomic analyses are needed to define fusions in patients without point mutations in kinases and those alterations that cooperate with kinase mutations in histiocytoses.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure Statement: Nothing to disclose.

Contributor Information

Neval Ozkaya, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Department of Pathology, ozkayan@mskcc.org, 1275 York Avenue, New York, NY, 10065, USA

Ahmet Dogan, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Department of Pathology, dogana@mskcc.org, 1275 York Avenue, New York, NY, 10065,USA

Omar Abdel-Wahab, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Human Oncology and Pathogenesis Program, abdelwao@mskcc.org, 1275 York Avenue, New York, NY, 10065, USA

References

- 1.Hutter C, et al. Notch is active in Langerhans cell histiocytosis and confers pathognomonic features on dendritic cells. Blood. 2012;120(26):5199–208. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-410241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen CE, et al. Cell-specific gene expression in Langerhans cell histiocytosis lesions reveals a distinct profile compared with epidermal Langerhans cells. J Immunol. 2010;184(8):4557–67. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berres ML, et al. BRAF-V600E expression in precursor versus differentiated dendritic cells defines clinically distinct LCH risk groups. J Exp Med. 2014;211(4):669–83. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J, Vardiman JW. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Fourth. Vol. 2. WHO Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emile JF, et al. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016;127(22):2672–81. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-690636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Badalian-Very G, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116(11):1919–23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-279083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haroche J, et al. High prevalence of BRAF V600E mutations in Erdheim-Chester disease but not in other non-Langerhans cell histiocytoses. Blood. 2012;120(13):2700–3. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-430140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hervier B, et al. Association of both Langerhans cell histiocytosis and Erdheim-Chester disease linked to the BRAFV600E mutation. Blood. 2014;124(7):1119–26. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-543793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Go H, et al. Frequent detection of BRAF(V600E) mutations in histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms. Histopathology. 2014;65(2):261–72. doi: 10.1111/his.12416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kansal R, et al. Identification of the V600D mutation in Exon 15 of the BRAF oncogene in congenital, benign langerhans cell histiocytosis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2013;52(1):99–106. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rollins BJ. Genomic Alterations in Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2015;29(5):839–51. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kordes M, et al. Cooperation of BRAF(F595L) and mutant HRAS in histiocytic sarcoma provides new insights into oncogenic BRAF signaling. Leukemia. 2016;30(4):937–46. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakajima Y, et al. NR4A1 (Nur77) mediates thyrotropin-releasing hormone-induced stimulation of transcription of the thyrotropin beta gene: analysis of TRH knockout mice. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40437. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chakraborty R, et al. Alternative genetic mechanisms of BRAF activation in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2016;128(21):2533–2537. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-08-733790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Estep AL, et al. Mutation analysis of BRAF, MEK1 and MEK2 in 15 ovarian cancer cell lines: implications for therapy. PLoS One. 2007;2(12):e1279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanrahan AJ, et al. Genomic complexity and AKT dependence in serous ovarian cancer. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(1):56–67. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeck WR, et al. Targeted next generation sequencing identifies clinically actionable mutations in patients with melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27(4):653–63. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown NA, et al. High prevalence of somatic MAP2K1 mutations in BRAF V600E-negative Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2014;124(10):1655–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-577361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chakraborty R, et al. Mutually exclusive recurrent somatic mutations in MAP2K1 and BRAF support a central role for ERK activation in LCH pathogenesis. Blood. 2014;124(19):3007–15. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-577825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson DS, et al. Somatic activating ARAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2014;123(20):3152–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-511139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diamond EL, et al. Diverse and Targetable Kinase Alterations Drive Histiocytic Neoplasms. Cancer Discov. 2016;6(2):154–65. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson DS, et al. MAP2K1 and MAP3K1 mutations in langerhans cell histiocytosis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2015;54(6):361–8. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiu A, Ozkaya N, Dogan A. Oncogenic MAP2K1 mutation in a transdifferentiated histiocytic sarcoma. European Association for Haematopathology Meeting. Basel. 2016 LYWS Case 372.. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emile JF, et al. Recurrent RAS and PIK3CA mutations in Erdheim-Chester disease. Blood. 2014;124(19):3016–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-570937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozono S, et al. Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia characterized by cutaneous lesion containing Langerhans cell histiocytosis-like cells. Int J Hematol. 2011;93(3):389–93. doi: 10.1007/s12185-011-0787-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Q, et al. Hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis in mice expressing oncogenic NrasG12D from the endogenous locus. Blood. 2011;117(6):2022–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-280750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heritier S, et al. Common cancer-associated PIK3CA activating mutations rarely occur in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2015;125(15):2448–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-01-625491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown RA, et al. ETV3-NCOA2 in indeterminate cell histiocytosis: clonal translocation supports sui generis. Blood. 2015;126(20):2344–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-07-655530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chakraborty R, et al. Alternative genetic mechanisms of BRAF activation in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2016 doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-08-733790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee LH, et al. Real-time genomic profiling of histiocytoses identifies early-kinase domain BRAF alterations while improving treatment outcomes. JCI Insight. 2017;2(3):e89473. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.89473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takeuchi K, et al. KIF5B-ALK, a novel fusion oncokinase identified by an immunohistochemistry-based diagnostic system for ALK-positive lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(9):3143–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soda M, et al. Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2007;448(7153):561–6. doi: 10.1038/nature05945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiesner T, et al. Kinase fusions are frequent in Spitz tumours and spitzoid melanomas. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3116. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agaram NP, et al. Recurrent NTRK1 Gene Fusions Define a Novel Subset of Locally Aggressive Lipofibromatosis-like Neural Tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40(10):1407–16. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang L, et al. Identification of a novel, recurrent HEY1-NCOA2 fusion in mesenchymal chondrosarcoma based on a genome-wide screen of exon-level expression data. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51(2):127–39. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mesquita B, et al. Frequent copy number gains at 1q21 and 1q32 are associated with overexpression of the ETS transcription factors ETV3 and ELF3 in breast cancer irrespective of molecular subtypes. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138(1):37–45. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2408-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carapeti M, et al. A novel fusion between MOZ and the nuclear receptor coactivator TIF2 in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 1998;91(9):3127–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deguchi K, et al. MOZ-TIF2-induced acute myeloid leukemia requires the MOZ nucleosome binding motif and TIF2-mediated recruitment of CBP. Cancer Cell. 2003;3(3):259–71. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strehl S, et al. ETV6-NCOA2: a novel fusion gene in acute leukemia associated with coexpression of T-lymphoid and myeloid markers and frequent NOTCH1 mutations. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(4):977–83. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sumegi J, et al. Recurrent t(2;2) and t(2;8) translocations in rhabdomyosarcoma without the canonical PAX-FOXO1 fuse PAX3 to members of the nuclear receptor transcriptional coactivator family. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010;49(3):224–36. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hyman DM, et al. Vemurafenib in Multiple Nonmelanoma Cancers with BRAF V600 Mutations. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(8):726–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Diamond Eli L, VS, Lockhart Craig, Blay Jean-Yves, Faris Jason E, Puzanov Igor, Chau Ian, Raje Noopur S, Wolf Jürgen S, Erinjeri Joe, Torrisi Jean, Ulaner Gary, Lacouture Mario, Robson Susan, Makrutzki Martina, Elez Elena, Tabernero Josep, Abdel-Wahab Omar, Baselga Jose, Hyman David M. Vemurafenib in Patients with Erdheim–Chester Disease (ECD) and Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH) Harboring BRAFV600 Mutations: A Cohort of the Histology-Independent VE-Basket Study (2016 ASH abstract) 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haroche J, et al. Reproducible and sustained efficacy of targeted therapy with vemurafenib in patients with BRAF(V600E)-mutated Erdheim-Chester disease. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(5):411–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kieran Mark W, DRH, Cohen Kenneth J, Aerts Isabelle, Dunkel Ira J, Hummel Trent Ryan, Jimenez Irene, Pearson Andrew DJ, Pratilas Christine A, Whitlock James, Bouffet Eric, Violet Shen Wei-Ping, Broniscer Alberto, Bertozzi Anne-Isabelle, Sandberg Joan L, Florance Allison M, Suttle Benjamin B, Haney Pat, Russo Mark W, Geoerger Birgit. Phase 1 study of dabrafenib in pediatric patients (pts) with relapsed or refractory BRAF V600E high- and low-grade gliomas (HGG, LGG), Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), and other solid tumors (OST) (2015 ASCO Abstract) 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nordmann TM, et al. Trametinib after disease reactivation under dabrafenib in Erdheim-Chester disease with both BRAF and KRAS mutations. Blood. 2017;129(7):879–882. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-740217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohen Aubart F, et al. Efficacy of the MEK inhibitor cobimetinib for wild-type BRAF Erdheim-Chester disease. Br J Haematol. 2016 doi: 10.1111/bjh.14284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Emery CM, et al. MEK1 mutations confer resistance to MEK and B-RAF inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(48):20411–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905833106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Azorsa David, DWL, Bista Ranjan, Henry Michael, Arceci Robert John. Association of clinical and biological resistance with a novel mutation in MAP2K1 in a patient with Langerhans cell histiocytosis (2016 ASCO Abstract) J Clin Oncol. 2016;34 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Diamond Eli L, BHD, Dogan Ahmet, Hyman David M, Rampal Raajit, Ulaner Gary, Brody Lynn, Abdel-Wahab Omar. Phase 2 Trial of Single-Agent Cobimetinib for Adults with Histiocytic Disorders: Preliminary Results (2016 ECD Global Alliance Abstract) 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Larkin J, et al. Combined vemurafenib and cobimetinib in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(20):1867–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gianfreda D, et al. Sirolimus plus prednisone for Erdheim-Chester disease: an open-label trial. Blood. 2015;126(10):1163–71. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-01-620377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swerdlow SH, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127(20):2375–90. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-643569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hyman DM, et al. Prospective Blinded Study of BRAFV600E Mutation Detection in Cell-Free DNA of Patients with Systemic Histiocytic Disorders. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(1):64–71. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]